The New Climate War

Air Date: Week of March 5, 2021

The New Climate War: The Fight to Take Back Our Planet is Michael Mann’s latest book, about how the fossil fuel industry funds climate change denial campaigns to try to block climate action. (Photo: Courtesy of Bold Type Books)

Despite rising global temperatures and an increase in climate change-related natural disasters, climate denial still runs rampant. As renowned climatologist Michael Mann describes in his latest book, The New Climate War: The Fight to Take Back Our Planet, key major fossil fuel companies have spent decades deflecting blame and responsibility in order to delay action on climate change. As part of our LOE Book Club series, Professor Mann joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about the fight against climate denialism and inaction in all its forms.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

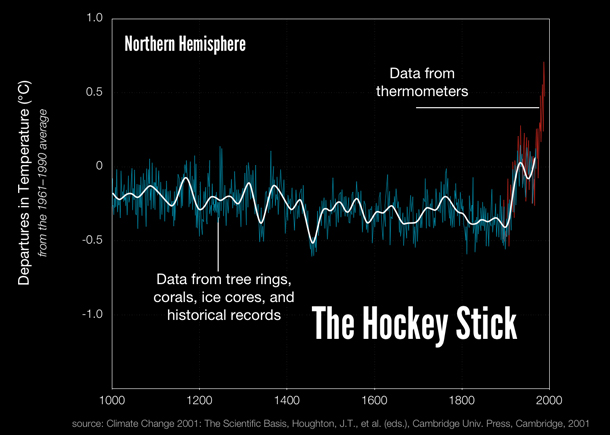

Two decades ago, to critical acclaim, Penn State professor Michael Mann wrote the Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars. It included a chart resembling a hockey stick showing the explosive growth in human-caused CO2 emissions that are heating the planet. He now has a new book called, The New Climate War: The Fight to Take Back Our Planet, in which he describes the decades-long history of fossil fuel companies deflecting blame and responsibility in order to delay action on climate change. Professor Mann was also the target of a disinformation campaign in which the emails of climate scientists were hacked and taken out of context to malign climate science. I caught up with Professor Mann to talk about The New Climate War as a part of our Living on Earth Book Club series with a live audience. Michael, how are you? Welcome back to Living on Earth!

MANN: Doing okay, good to see you, my friend.

CURWOOD: Great to see you. You know, by the way, the other day I was looking at methane emissions, and I'm thinking maybe you need to have a double hockey stick, I didn't realize that they had doubled since the 1920s.

MANN: Indeed, and we can talk more about sort of the state of, you know, play when it comes to the climate crisis. And, you know, it's it's an important time, for the first time in some number of years, I would say there are legitimate reasons for cautious optimism. But there is still great urgency as you allude to. Methane continues to rise, that's contributing to warming. There are a lot of components of this problem that we need to get to work on. And that's where we are. So there's great urgency, but there's also agency and I think we're now at a pivotal moment, where we may indeed, finally see the sort of action that we need to see.

CURWOOD: Your book tells the story, in no small measure of your role, really, as a warrior dealing against denialism about the climate. Just tell us a little bit of your story against denial, and how it is that you have really been on this march to take it away. Maybe you want to start with the trouble you got with the hacked emails or the trouble that you had with tenure. Or you just simply might tell us how it is that one addresses denial in the face of reality?

MANN: Yeah, well, you know, we could go all the way back to elementary school and some of the trouble I got in there for challenging authority. You know, sometimes you do need to speak truth to power. And when it comes to the climate crisis, we have some very powerful, for lack of a better word, enemies: those who would gladly continue to lead us down the path of climate destruction because they continue to make huge profits from our addiction to fossil fuels. And there are enlightened players, you know, CEOs and employees and companies in the fossil fuel industry that recognize that we need to pivot, that it's time to change. But there's still some holdouts, and they continue to fund efforts aimed not so much anymore at denying climate change. Whether you're down in Australia on the west coast, if you witnessed the wildfires this last season on the Gulf Coast, and you experienced this record hurricane season, the impacts of climate change, they're playing out in front of us. So it's not credible to deny that climate change is real and happening. Instead, the forces of inaction, and in the book I call them the inactivists.

CURWOOD: Yeah, that's a great, that's a great sobriquet...

The famous “hockey stick” graph, showing time reconstructions [blue] and instrumental data [red] for Northern Hemisphere mean temperature. In both cases, the zero line corresponds to the 1902-80 calibration mean of the quantity. Raw data are shown up to 1995. The thick white line corresponds to a lowpass filtered version of the reconstruction. (Photo: Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis, Houghton, J.T., et al. (eds.), Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2001)

MANN: I would love, I would love to take credit for it. I believe the term was coined by my friend Joe Romm, who was a great communicator, in fact, and it does capture, you know, the ultimate goal, whether it's denial, delay, distraction, deflection, division, any tactic now that will prevent us from leaving behind our addiction to fossil fuels, transitioning to renewable energy, even though it's what we need to do collectively, there are some vested interests who are going to see their bottom line hurt, their profits hurt if we get off of this addiction to fossil fuels, and they've used every means available to them, if not to prevent entirely that transition, at least to slow it down. Because every year we remain addicted to fossil fuels, they continue to make billions of dollars of profit. So at this point, the writing's on the wall, they see that the writing's on the wall, but they are seeking to delay this necessary transition. And the problem is there is no room for delay at this point. We can't afford delay. And we need to bring carbon emissions down by a factor of two within the next decade to remain on course to keeping warming below catastrophic levels. And so yeah, the hockey stick two decades ago, sort of, I suppose, captured the public imagination, you didn't need to understand the complexities of climate science to understand what this curve was telling us with this sort of slight cooling a thousand years ago into the Little Ice Age. Think of that as the handle of a hockey stick. And then the abrupt warming of the past century and half, the upturned blade. It really I think communicated very clearly the profound impact that we're having. And so it was a threat to the vested interests who have tried to prevent that needed transition. I found myself under attack, the stolen emails that were used, you know. Does this sound familiar? Emails that were stolen to try to impact an important political event?

CURWOOD: Yes, emails stolen, that actually didn't turn out to be anything.

MANN: Yeah, the 2009 Copenhagen summit, but it was the first opportunity in years for meaningful progress on climate change. And there were some powerful actors we've talked about. In fact, petro-state actors, Russia probably played a role in this, who didn't want to see progress made in Copenhagen. Their main asset is the fossil fuels that are still buried beneath their ground. surface and they have an agenda to extract and sell those fossil fuels. And they've done everything they can to block international action on climate. There's a whole story about the last presidential election, the 2016 election, the role that Russia played, and the extent to which that might actually have been about sanctions against Russia over Ukraine that prevented a half trillion dollar oil deal between RussNeft, the Russian oil company, and ExxonMobil.

CURWOOD: So Michael, a little math here for a moment. Russia's GDP is on the scale of $2 trillion. Right?

MANN: Right.

CURWOOD: And the amount of hydrocarbons they export, is what, more than half of that, right? You look at Saudi Arabia, and almost all their economy is based on exporting hydrocarbons, gas and oil. And then the US does have a $20 trillion GDP. But guess what? We're in the top three producers and exporters of hydrocarbons on the planet.

Much of the fossil fuel industry, including oil giants like ExxonMobil, has funded climate denial campaigns for decades. (Photo: Mike Mozart, Flickr, CC BY 2.0))

MANN: That's right.

CURWOOD: So, to what extent do you think that Mr. Trump and Mr. Putin saw common interest in making sure that the good times keep rolling for the oil industry?

MANN: Yeah, I think that's the dirty secret about what probably was behind what we now refer to as RussiaGate. And the great irony being that 10 years ago, the event you refer to, ClimateGate, the stolen emails that were used to discredit scientists, including myself by taking words out of context from these emails, like trick, which is used by mathematicians and scientists to denote a clever approach to solving a problem. But to the public, hey, it sounds like you're trying to play a trick on people. We can't trust these scientists. And it was very effectively used to sow distrust of the science, doubt going into the Copenhagen summit. Who do we know was implicated? Russia, the Russian servers were used to host the stolen emails, WikiLeaks played a role. And it was about thwarting action on climate, it was about fossil fuels. That was sort of a test run for what Russia did. You know, in the again, six years later, 2016 with the previous presidential election, where the same players were involved: stolen emails used to discredit Hillary Clinton, and help hand the election to Donald Trump, who, as you note had an alignment in interest when it comes to the fossil fuel agenda of Russia and his supporters in the fossil fuel industry here in the United States.

CURWOOD: And don't forget Saudi Arabia, where Mr. Trump spent an awful lot of time.

MANN: Oh, I call them the coalition of the unwilling a number of petro-states who have formed this coalition that is opposed to any meaningful action on climate and it's Saudi Arabia, and Russia, Australia has sort of fallen into that, although I think they may be on their way out based on my experiences there. But small number of bad apples if you will, spoiling it for the rest of the planet.

CURWOOD: So science denial, has been on the rise for a good while. I mean, if Naomi Oreskes were with us right now, the Harvard professor, she'd be saying it's been going on since really the end of our enthusiasm about space. What similarities do you see between how the science of the COVID-19 pandemic and measures to deal with it? What similarities you see about the denial around that by a number of people, as opposed to the denialism that has been around about climate disruption?

MANN: Yeah, it's a great question. And you know, we could probably spend an hour talking about the lessons that we can draw from the pandemic, because there's so many of them when it comes to the larger problem here. But specifically, with regard to denial, I think that the pandemic really laid bare, how science denial is deadly. And we can measure that toll in hundreds of thousands of human lives when it comes to the agenda-driven effort to deny the public health science that told us we need to be engaged in social distancing, mask wearing. These practices were viewed as adverse to the agenda of Donald Trump, adverse to him being reelected. And of course, if he didn't get reelected, then a lot of these interests the fossil fuel interests, who were able to run the show on energy and environmental policy under Trump would lose their ability to implement their agenda as well, because make no mistake in four years, Donald Trump dismantled much of the past 50 years of environmental progress. The good news is that he didn't get a second term and we probably can undo most of the damage and that's what the Biden administration is going to need to do in the beginning, just undo the damage that was done before we can really start to make progress. But it was agenda-driven science denial, just like climate change denial. The difference is the accelerated timeframe on which it played out allowed us to view literally in individual lives, the deadliness of science denial, and I hope that that is a lasting legacy, a lasting message. Maybe it gives us a real opportunity now to turn the corner on some of these other issues, like climate change. And I do think we're largely past climate denial, now, for an array of reasons. This is one of them. But just the fact that we can see the impacts playing out in real time, it's not credible to deny them. So instead, the forces of inaction have turned to other tactics, which I'm sure we'll get into, to try to slow down this transition. But I think we are maybe at the cusp of finally putting this sort of science denial behind us. That doesn't mean there isn't going to be, you know, a fringe of science deniers, people who are not engaged in fact-based discourse, who do live in an alternative universe of alternative facts. We're sort of stuck with that problem, I think, for some time, but I think the majority of the American public are increasingly on board.

CURWOOD: There's another similarity I'm thinking of regarding the COVID 19 pandemic and climate disruption. And that is the hollowing out of the whole scientific community in the regulatory agencies. I mean, some 45,000 public health workers at all levels of government, whether at the federal or the state or the town, those jobs vanished over the last decade. I'm old enough to remember the you know, the town always had a public health officer, people didn't necessarily like that person, because he was going in and out of restaurants and slapping a "don't eat here", or showing up with a needle or even trying to track down a sexually transmitted disease situation that people were embarrassed about. But my God, we don't have anybody in our communities right now who know what to do to distribute vaccines, do we?

MANN: Yeah, you know, there's a lot of infrastructure that we need to build back. And you know, that's one of the things I like about this administration's motto is the recognition of that: build back better, we've got to build back. I hope they interpret that mandate broadly, right? Because that's not just at the federal level, as you allude to, that penetrates all the way down to the local level. We've, you know, for various reasons, lost so much of this critical infrastructure. And we've seen the cost of not having that infrastructure.

CURWOOD: I have a question that I want to play for you from one of the students at Boston College. And it's a Carli Brenner. And let me ask our producers if they could roll that bit of video.

Part of the Russian government’s interference in the 2016 US Presidential Election is speculated to have ties to fossil fuel interests and climate inaction. At the 2017 G-20 Hamburg Summit, US President Donald Trump (center right) and Russian President Vladimir Putin (center left) met alongside Russia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov (far left), and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson (far right). Rex Tillerson, when he was the CEO of ExxonMobil, represented Exxon’s interests in Russia and was once awarded Russia’s Order of Friendship. (Photo: Kremlin.ru, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

BRENNER: Hi, my name is Carli Brenner. I'm a senior at Boston College, and I'm majoring in political science, with minors in environmental studies and management and leadership. And Dr. Mann, my question for you is about how today, people's beliefs about climate change have become really tied to their individual political identity. So how can we separate climate change from the political realm so that climate action can be seen as a nonpartisan movement rather than a win or a loss for either side of the political spectrum? Thank you.

MANN: Yeah. Thanks so much, Carli, it's a great question. I love the fact that you're sort of combining public policy and environmental studies in your studies, because that intersection is going to be so important moving forward in solving the great problems that we face. And we do need your generation to help solve some of the problems that my generation has created. And I'm confident we will. And part of the solution, I think, as you allude to, is we need to de-politicize science. It's become convenient, unfortunately, for, you know, certain powerful interests to sort of mobilize people against the findings of science. We saw that with COVID-19. And, of course, we've seen that with climate change over an even longer timeframe. I have some hope that we will get past that for a few reasons. I could be wrong. But I think that we had sort of a moment now over the past several years, where we've sort of looked into the abyss. And I don't think collectively, we've liked what we saw, we've seen the death and destruction that results from our unwillingness to listen to what science and what scientists have to say. And so I do think there's a newfound respect, not among all and again, Steve and I were just talking about that: there is this contingent that's sort of been weaponized now by four years of Trumpism. And they're going to be there for some time. And we're gonna need to contend with that. We're not going to win everybody over to the side of fact-based discourse and science-based policy. But I do think that we can put together a winning majority for action on these fronts, and that majority will consist of not just progressives and Democrats, but I think moderate Republicans, moderate conservatives, who do not like the direction that they've seen their party move in. And I think the reaction from that will actually lead them into sort of a more collaborative framework when it comes to working on problems like climate change. Part of the reason I'm optimistic about that is sort of the generational component to this. Obviously, there's the youth climate movement. And that is really inserted in a very profound way, sort of intergenerational ethics into this discussion. And I think that's so important. But there's also just the fact that if you look at polling, I believe it's something like 70% of Republicans under the age of 40, which to me, sounds really young these days.

Michael Mann and Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood in 2019. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: Time flies, Michael, when you're having a good time.

MANN: I know, I know. It sounds so young. So you know, yeah, that is young, under 40. Young republicans. 70% are on board. Climate change is real. It's a problem. We need to do something about it. I think the writing's on the wall. You see some of the same conservative pundits and pollsters, like Frank Luntz, who actually helped Republicans in the fossil fuel industry in their messaging to defeat climate action back sort of in the Clinton era. Well, Frank Luntz is flipped now. He's actually been helping Democrats with their messaging, because he recognizes that this is a real problem. And I think he and his generation of Republicans don't want to be responsible, they don't want to be seen as having been on the wrong side of history with what is arguably the greatest and most important challenge that we face. So for those reasons, and just sort of the new political blood with Biden, his administration and the actions he's already taking, and the prospects for climate action in the US Congress now to complement his executive agenda. All of these reasons make me optimistic, you know, that we will bring more, you know, moderate conservatives into the fold, that there will be this, you know, Coalition for climate action, that will be bipartisan. Some people are going to be left behind, we're not going to win everybody over. But you know, no political movement has ever, you know, had 100% of the public on board, I think we have a very motivated and a very righteous coalition here for action.

CURWOOD: Well, spoiler alert, if we don't all get engaged in this in some level or another, and not in that personal way, because at one point in your book, you talk about how some of the inactivists push people to feel that, well, if you're gonna deal with climate, you need to drive the right car or recycle the right way, that keeping us from looking at collective action. But yeah, we can't do this without collective action. We don't have the power to have charging stations for an electric car. I mean, we don't have the power to change our agricultural system so that they sequester carbon instead of releasing it. We don't have the power to change so many of these things as individuals, but we can collectively.

MANN: Absolutely, Steve, You and I can't block the additional fossil fuel infrastructure. You and I can't take away subsidies for the fossil fuel industry. We can't provide subsidies for renewable energy, we can't put a price on carbon. We need our policymakers to do those things. We can't solve this problem without them, instituting those systemic changes that we ourselves, can't alone. But we can use our voice. And that's what makes me so optimistic. Over the last, you know, several years, we've seen young people using that voice. And we've all used our voice collectively at the polls, to elect politicians. Look, elections have consequences. We have a president who ran on climate, has a mandate on climate, and is now leading on climate, and he's got a Democratic Congress that's going to help him do that. And it wouldn't have happened if this coalition that we talked about hadn't come out and demanded change. And so that's why I'm optimistic. It's late in the game. It's, you know, the fourth quarter, and we're down to touchdown or two. I won't use a Patriots analogy here, I'll resist that temptation. But but the game isn't over. And in fact, the game is very winnable.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann is a professor of atmospheric sciences at Penn State and author of the book, The New Climate War: The Fight to Take Back Our Planet. Our conversation with Professor Mann is part of our ongoing live event series, the Living on Earth Book Club. Our book club meets next on March 11th at 4:30 pm Eastern, and you are invited. We’ll be talking to the daughter of Katherine Johnson, an African American woman who worked as a mathematician for NASA starting in the 1950s. Her work, chronicled in the movie Hidden Figures, helped safely land the first man on the moon at a time when segregation was still law for much of the land. Katherine’s daughter, also named Katherine, worked on a children’s book with her family about her mother’s accomplishments at NASA shortly before her mother passed away. It’s sure to be a thought-provoking conversation so please join us on March 11th at 4:30 pm Eastern. To register go to the Living on Earth website, loe dot org slash events.

Links

Learn more about The New Climate War

Affiliate book link for The New Climate War (Link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth