March 5, 2021

Air Date: March 5, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Radioactive Water Dilemma at Fukushima

View the page for this story

Ten years after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant disaster, millions of gallons of radioactive cooling water are about to overflow storage tanks. Japanese authorities are looking at the option of releasing it into the Pacific Ocean. Arjun Makhijani, President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to mark the tenth anniversary of the reactor core meltdowns and what the release of the contaminated water into the ocean could mean for marine and human health. (10:36)

The New Climate War

View the page for this story

Despite rising global temperatures and an increase in climate change-related natural disasters, climate denial still runs rampant. As renowned climatologist Michael Mann describes in his latest book, The New Climate War: The Fight to Take Back Our Planet, key major fossil fuel companies have spent decades deflecting blame and responsibility in order to delay action on climate change. As part of our LOE Book Club series, Professor Mann joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about the fight against climate denialism and inaction in all its forms. (19:46)

Hard Times for Ginseng Farmers

/ Aaron MokView the page for this story

Consumers in China and the U.S. prize American ginseng, most of which is grown in just one Wisconsin county, as a health food and traditional medicine. But demand has dried up in the midst of America’s ongoing trade war with China, economic impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic and anti-Asian rhetoric. Living on Earth’s Aaron Mok wrote about the crisis for Civil Eats and joins Host Bobby Bascomb to share the stories of ginseng farmers he interviewed. (05:02)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week's Beyond the Headlines segment, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood learn about a group of rescued Bornean orangutans that were released back into the wild via helicopter to minimalize COVID risk. Next, they unravel an unexpected link between glyphosate use on banana plantations and the release of another pesticide stored in the soils. Finally, they travel back to the tragic 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill, and the twenty-year legal battle that ensued between the State of Alaska and Exxon executives. (04:41)

Nature and the Beat

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

From the chirp of a Katydid to the screech of a parrot, the sounds of nature are all around us and now can be used to help humans make music. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports on Beast Box, a website that allows users to create their own unique songs using catchy beats and animal calls as the instruments. (06:10)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

210305 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Arjun Makhijani, Michael Mann, Aaron Mok

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

Ten years after the Fukushima nuclear meltdown radioactive wastewater is being released into the ocean.

MAKHIJANI: They're dumping mostly tritiated water which is radioactive water. You know, radioactive water crosses the placenta, this radiation can disrupt the reproductive and energy systems of all the beings there and they haven't even looked at that.

CURWOOD: Also, vilifying science can have deadly consequences for public health and the climate.

MANN: It's become convenient, unfortunately, for certain powerful interests to sort of mobilize people against the findings of science. We saw that with COVID-19, and of course we've seen that with climate change over an even longer time frame.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Radioactive Water Dilemma at Fukushima

Two IAEA experts examine recovery work on top of Unit 4 of TEPCO's Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station on 17 April 2013 as part of a mission to review Japan's plans to decommission the facility. (Photo: Greg Webb, Flickr, IAEA, CC BY SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

At quarter to three in the afternoon of March 11th, 2011, a magnitude 9 earthquake moved the main island of Japan eight feet, and launched a tsunami four stories high into the region of Fukushima, Japan, killing thousands and flooding a nuclear power complex.

[SFX https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=spg62-MrYpQ]

BASCOMB: In the hours and days that followed, the cooling systems failed and the uranium cores in the three operating nuclear power reactors partially melted down releasing deadly radiation. Authorities were eventually forced to evacuate an eighty square mile zone around Fukushima. It was the worst nuclear accident in history with the exception of Chernobyl in 1986, and the Fukushima accident is not over yet. At least 2 cooling pools to prevent further meltdowns in the broken reactors are leaking into the ocean, forcing the pumping in of even more water. TEPCO, the Toyko Electric Power Company that operates the complex, will run out of space to store the radioactive water sometime next year. TEPCO and the Japanese government have plans to dump much of it into the Pacific Ocean, leading to an outcry from the public. For more I’m joined now by Arjun Makhijani, President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research. Arjun, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MAKHIJANI: Thank you for having me back. I love being on living on Earth.

BASCOMB: We've always been told that the solution to pollution is dilution and the Pacific Ocean is very, very large far dwarfs the water they would be releasing into it. What do you say to that argument?

Japan's Emperor Akihito (L) and Empress Michiko visit at an area which was devastated by the March 11 earthquake and tsunami in Soma, Fukushima prefecture, about 50km from the crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, May 11, 2011, on the two-month anniversary of the quake and tsunami. (Photo: Greg Webb , Reuters, Flickr, CC BY SA 2.0)

MAKHIJANI: Yeah, now they're not going to pump the whole Pacific Ocean and dilute it in the whole Pacific Ocean, that's one thing, they're not going to do that. So, they're going to dump it near the shore, the vertical mixing in the oceans is extremely slow. So, it is going to remain for some time in the surface waters. Of course, it will be diluted somewhat, so it will impact the shore more, but tritium has a half-life of 12.3 years. There's also a lot of strontium which mimics calcium in the body. Now, one thing to know about strontium 90, because it mimics calcium it goes to the bones, it becomes part of the bone marrow. Our immune system stem cells arise in the bone marrow. And the immune system of the fetal development is more complicated but it is a hematopoietic system and when you are putting radioactivity into a place where your immune stem cells are originating, you're compromising all aspects of health. And these are aspects of radioactivity that have not been adequately studied. And I think before an organization like TEPCO is allowed to pollute the oceans with strontium and tritium, which can cross the placenta, not only in human beings, so you know, we're not going to drink seawater, but the biological systems, the reproductive systems, the energy system, specially, a lot of our immune systems are very common between human beings and a large variety of animals, including fish. And so I think it should be on them to demonstrate that this is not going to severely disrupt the reproductive and energy systems of the living beings where they are going to dump this.

BASCOMB: Well, you can see how Japan is in a real pickle here. I mean, the cooling pools are filling with this radioactive water, they can't keep it there forever. What are their alternatives are there for them?

MAKHIJANI: Yeah, dumping it in the oceans is the most polluting, and in my opinion, the worst, they can evaporate it slowly and emitted into the air, there is some natural tritium that mother nature makes in the atmosphere, if it is small relative to that the ecological impact would be much lower. And the third option is simply to extract the tritium separating the treaded water would isolate it concentrated, and it could be used in biological research and exit signs and so on. It is proposed to be used in fusion reactors, you know, a large one is being built in France. It could be mixed with cement and put in storage for the long term. And one of the things is that the long term storage would be, you're talking 70 or 80 years by which time it would almost totally decay away. So, there are options available that have much, much less ecological impact, they are more costly. But in the scale of decommissioning costs, and dealing with the Fukushima, none of these alternatives appeared to be very costly. So we're talking about decades, and hundreds of billions of dollars, but then think that you are setting a precedent for how to handle a difficult situation in a way that's respectful of future generations that’s respectful of ecosystems and that's respectful of your neighbors.

The Japanese government alongside TEPCO (Tokyo Electric Power) are planning on dumping 1.2 million tons of water contaminated by radioactive substances from the Fukushima disaster into the Pacific Ocean. (Photo: Dean Calma, Reuters, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: You know, of course, there's an exclusion zone around the Fukushima facility, and I've read that like Chernobyl, there's actually all manner of wildlife returning to that area, things like wild boars and snow monkeys. I don't know is that perhaps a small silver lining here?

MAKHIJANI: Well, you know, we saw that in the pandemic, too when the economies were shut down, wildlife started coming back all over the place. The difference here is that this wildlife is now in a radioactive environment. There's been a fair amount of research in Chernobyl as to the genomes of the creatures that inhabit the Chernobyl contaminated zone. And there has been significant genetic damage to this. So it's not like you're bringing pristine wildlife and then, you know, nuclear accidents cause human beings to withdraw and therefore Mother Nature will be happy. No, to the extent that I can tell Mother Nature, in the sense of respecting the genomes of the creatures as Mother Nature has evolved them is not happy.

BASCOMB: You know, it's disasters like Fukushima that have people so concerned about the safety of nuclear power. But at the same time, much of the world, including President Biden, and the US is pledged to decarbonize their economies to avert the worst-case scenario for climate change. And nuclear can be a component of that. How can we square the need to rapidly decarbonize and the legitimate concerns about the safety of nuclear energy? And for that matter, how to handle the nuclear waste that comes along with it?

Arjun Makhijani is President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research and author of books focused on the safety, economics and efficacy of various energy sources including nuclear, wind and solar. (Photo: Courtesy of Arjun Makhijani)

MAKHIJANI: Okay, so I've looked at this problem as an electrical engineer, there is a shortage of two things I think we can all agree, there's a shortage of time, because we've wasted so much and not done things early enough 30 years ago when we should have started, and there's a shortage of money. There's not a shortage of low carbon electricity sources. I have done an hour-by-hour assessment over a four year period of can you actually have a solar and wind electricity system almost exclusively, with smart grids and storage and peaking electricity supply. A lot of technical paraphernalia around the solar and wind system. Can you make it work reliably? And what will it cost? Suppose you did not have nuclear. And the answer to that, to my own surprise, I concluded that it was possible, feasible and economical. Now 14 years ago, I thought it would be very difficult, because that was a time when solar energy was still very expensive. And battery storage of electricity was also very expensive. Now, things in the energy sector have undergone an absolute technical revolution in the last 14 years. Solar and wind electricity are now the cheapest sources of new electricity. That's not Arjun talking, that's Wall Street talking. Wall Street firm, Lazard publishes a cost estimate every year of the costs of new electricity sources. Solar and wind are estimated about $40 a megawatt hour nuclear is estimated at about $160 a megawatt hour about four times as much. Now solar and wind need, you know, battery storage demand response, they need other things, but that delta between 40 and 160 is vast. You can accommodate a reliable, resilient, renewable energy system for cheaper than doing nuclear. From a time and climate urgency point of view alone, we should not be investing in nuclear. Then you can look at the field history of nuclear power to address climate change in this country. Fifteen years ago when Congress started taking up the issue of climate there was also announced a nuclear Renaissance that was about 2005 in the Energy Policy Act that was passed that year. There were applications for more than 30 reactors as a result of this, you know, government support streamline licensing, it was all going to happen, modular reactors. Of those more than 30 reactors, essentially, all are dead except two. Two are being built in Georgia, Vogtle 3 and 4. They are hugely over cost and hugely delayed they were supposed to come online years ago. So this promise that nuclear was going to somehow solve the carbon problem has already failed and just purely from a business point of view we can't afford it.

BASCOMB: Arjun Makhijani is president of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research. Arjun, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

MAKHIJANI: Thank you very much for asking me.

Related links:

- AP News | “Newly Found Fukushima Plant Contamination May Delay Cleanup”

- Independent | “Radioactive Fukushima Waste Water Contains Substances which ‘Could Damage Human DNA’, Greenpeace Warns”

- Listen to Living on Earth’s report on Fukushima in 2017

[MUSIC: Yo-Yo Ma & The Silk Road Ensemble, feat. Roomful of Teeth, “Green (Vincent’s Tune)” on Sing Me Home, by Wu Man, Masterworks (Sony Music Entertainment)]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Climate scientist Michael Mann on how fossil fuel companies promote inaction on climate change. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Lewis Porter-Phil Scarff Group, “Bageshri-Bageshwari Part 1” on Three Minutes To Four, by Lewis Porter and Phil Scarff/based on a traditional raga, Whaling City Sound]

The New Climate War

The New Climate War: The Fight to Take Back Our Planet is Michael Mann’s latest book, about how the fossil fuel industry funds climate change denial campaigns to try to block climate action. (Photo: Courtesy of Bold Type Books)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

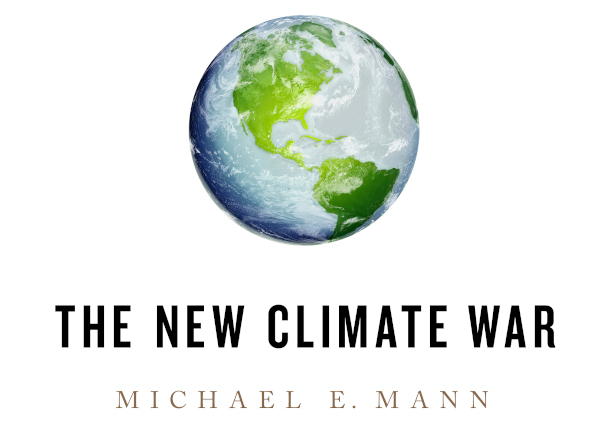

Two decades ago, to critical acclaim, Penn State professor Michael Mann wrote the Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars. It included a chart resembling a hockey stick showing the explosive growth in human-caused CO2 emissions that are heating the planet. He now has a new book called, The New Climate War: The Fight to Take Back Our Planet, in which he describes the decades-long history of fossil fuel companies deflecting blame and responsibility in order to delay action on climate change. Professor Mann was also the target of a disinformation campaign in which the emails of climate scientists were hacked and taken out of context to malign climate science. I caught up with Professor Mann to talk about The New Climate War as a part of our Living on Earth Book Club series with a live audience. Michael, how are you? Welcome back to Living on Earth!

MANN: Doing okay, good to see you, my friend.

CURWOOD: Great to see you. You know, by the way, the other day I was looking at methane emissions, and I'm thinking maybe you need to have a double hockey stick, I didn't realize that they had doubled since the 1920s.

MANN: Indeed, and we can talk more about sort of the state of, you know, play when it comes to the climate crisis. And, you know, it's it's an important time, for the first time in some number of years, I would say there are legitimate reasons for cautious optimism. But there is still great urgency as you allude to. Methane continues to rise, that's contributing to warming. There are a lot of components of this problem that we need to get to work on. And that's where we are. So there's great urgency, but there's also agency and I think we're now at a pivotal moment, where we may indeed, finally see the sort of action that we need to see.

CURWOOD: Your book tells the story, in no small measure of your role, really, as a warrior dealing against denialism about the climate. Just tell us a little bit of your story against denial, and how it is that you have really been on this march to take it away. Maybe you want to start with the trouble you got with the hacked emails or the trouble that you had with tenure. Or you just simply might tell us how it is that one addresses denial in the face of reality?

MANN: Yeah, well, you know, we could go all the way back to elementary school and some of the trouble I got in there for challenging authority. You know, sometimes you do need to speak truth to power. And when it comes to the climate crisis, we have some very powerful, for lack of a better word, enemies: those who would gladly continue to lead us down the path of climate destruction because they continue to make huge profits from our addiction to fossil fuels. And there are enlightened players, you know, CEOs and employees and companies in the fossil fuel industry that recognize that we need to pivot, that it's time to change. But there's still some holdouts, and they continue to fund efforts aimed not so much anymore at denying climate change. Whether you're down in Australia on the west coast, if you witnessed the wildfires this last season on the Gulf Coast, and you experienced this record hurricane season, the impacts of climate change, they're playing out in front of us. So it's not credible to deny that climate change is real and happening. Instead, the forces of inaction, and in the book I call them the inactivists.

CURWOOD: Yeah, that's a great, that's a great sobriquet...

The famous “hockey stick” graph, showing time reconstructions [blue] and instrumental data [red] for Northern Hemisphere mean temperature. In both cases, the zero line corresponds to the 1902-80 calibration mean of the quantity. Raw data are shown up to 1995. The thick white line corresponds to a lowpass filtered version of the reconstruction. (Photo: Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis, Houghton, J.T., et al. (eds.), Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2001)

MANN: I would love, I would love to take credit for it. I believe the term was coined by my friend Joe Romm, who was a great communicator, in fact, and it does capture, you know, the ultimate goal, whether it's denial, delay, distraction, deflection, division, any tactic now that will prevent us from leaving behind our addiction to fossil fuels, transitioning to renewable energy, even though it's what we need to do collectively, there are some vested interests who are going to see their bottom line hurt, their profits hurt if we get off of this addiction to fossil fuels, and they've used every means available to them, if not to prevent entirely that transition, at least to slow it down. Because every year we remain addicted to fossil fuels, they continue to make billions of dollars of profit. So at this point, the writing's on the wall, they see that the writing's on the wall, but they are seeking to delay this necessary transition. And the problem is there is no room for delay at this point. We can't afford delay. And we need to bring carbon emissions down by a factor of two within the next decade to remain on course to keeping warming below catastrophic levels. And so yeah, the hockey stick two decades ago, sort of, I suppose, captured the public imagination, you didn't need to understand the complexities of climate science to understand what this curve was telling us with this sort of slight cooling a thousand years ago into the Little Ice Age. Think of that as the handle of a hockey stick. And then the abrupt warming of the past century and half, the upturned blade. It really I think communicated very clearly the profound impact that we're having. And so it was a threat to the vested interests who have tried to prevent that needed transition. I found myself under attack, the stolen emails that were used, you know. Does this sound familiar? Emails that were stolen to try to impact an important political event?

CURWOOD: Yes, emails stolen, that actually didn't turn out to be anything.

MANN: Yeah, the 2009 Copenhagen summit, but it was the first opportunity in years for meaningful progress on climate change. And there were some powerful actors we've talked about. In fact, petro-state actors, Russia probably played a role in this, who didn't want to see progress made in Copenhagen. Their main asset is the fossil fuels that are still buried beneath their ground. surface and they have an agenda to extract and sell those fossil fuels. And they've done everything they can to block international action on climate. There's a whole story about the last presidential election, the 2016 election, the role that Russia played, and the extent to which that might actually have been about sanctions against Russia over Ukraine that prevented a half trillion dollar oil deal between RussNeft, the Russian oil company, and ExxonMobil.

CURWOOD: So Michael, a little math here for a moment. Russia's GDP is on the scale of $2 trillion. Right?

MANN: Right.

CURWOOD: And the amount of hydrocarbons they export, is what, more than half of that, right? You look at Saudi Arabia, and almost all their economy is based on exporting hydrocarbons, gas and oil. And then the US does have a $20 trillion GDP. But guess what? We're in the top three producers and exporters of hydrocarbons on the planet.

Much of the fossil fuel industry, including oil giants like ExxonMobil, has funded climate denial campaigns for decades. (Photo: Mike Mozart, Flickr, CC BY 2.0))

MANN: That's right.

CURWOOD: So, to what extent do you think that Mr. Trump and Mr. Putin saw common interest in making sure that the good times keep rolling for the oil industry?

MANN: Yeah, I think that's the dirty secret about what probably was behind what we now refer to as RussiaGate. And the great irony being that 10 years ago, the event you refer to, ClimateGate, the stolen emails that were used to discredit scientists, including myself by taking words out of context from these emails, like trick, which is used by mathematicians and scientists to denote a clever approach to solving a problem. But to the public, hey, it sounds like you're trying to play a trick on people. We can't trust these scientists. And it was very effectively used to sow distrust of the science, doubt going into the Copenhagen summit. Who do we know was implicated? Russia, the Russian servers were used to host the stolen emails, WikiLeaks played a role. And it was about thwarting action on climate, it was about fossil fuels. That was sort of a test run for what Russia did. You know, in the again, six years later, 2016 with the previous presidential election, where the same players were involved: stolen emails used to discredit Hillary Clinton, and help hand the election to Donald Trump, who, as you note had an alignment in interest when it comes to the fossil fuel agenda of Russia and his supporters in the fossil fuel industry here in the United States.

CURWOOD: And don't forget Saudi Arabia, where Mr. Trump spent an awful lot of time.

MANN: Oh, I call them the coalition of the unwilling a number of petro-states who have formed this coalition that is opposed to any meaningful action on climate and it's Saudi Arabia, and Russia, Australia has sort of fallen into that, although I think they may be on their way out based on my experiences there. But small number of bad apples if you will, spoiling it for the rest of the planet.

CURWOOD: So science denial, has been on the rise for a good while. I mean, if Naomi Oreskes were with us right now, the Harvard professor, she'd be saying it's been going on since really the end of our enthusiasm about space. What similarities do you see between how the science of the COVID-19 pandemic and measures to deal with it? What similarities you see about the denial around that by a number of people, as opposed to the denialism that has been around about climate disruption?

MANN: Yeah, it's a great question. And you know, we could probably spend an hour talking about the lessons that we can draw from the pandemic, because there's so many of them when it comes to the larger problem here. But specifically, with regard to denial, I think that the pandemic really laid bare, how science denial is deadly. And we can measure that toll in hundreds of thousands of human lives when it comes to the agenda-driven effort to deny the public health science that told us we need to be engaged in social distancing, mask wearing. These practices were viewed as adverse to the agenda of Donald Trump, adverse to him being reelected. And of course, if he didn't get reelected, then a lot of these interests the fossil fuel interests, who were able to run the show on energy and environmental policy under Trump would lose their ability to implement their agenda as well, because make no mistake in four years, Donald Trump dismantled much of the past 50 years of environmental progress. The good news is that he didn't get a second term and we probably can undo most of the damage and that's what the Biden administration is going to need to do in the beginning, just undo the damage that was done before we can really start to make progress. But it was agenda-driven science denial, just like climate change denial. The difference is the accelerated timeframe on which it played out allowed us to view literally in individual lives, the deadliness of science denial, and I hope that that is a lasting legacy, a lasting message. Maybe it gives us a real opportunity now to turn the corner on some of these other issues, like climate change. And I do think we're largely past climate denial, now, for an array of reasons. This is one of them. But just the fact that we can see the impacts playing out in real time, it's not credible to deny them. So instead, the forces of inaction have turned to other tactics, which I'm sure we'll get into, to try to slow down this transition. But I think we are maybe at the cusp of finally putting this sort of science denial behind us. That doesn't mean there isn't going to be, you know, a fringe of science deniers, people who are not engaged in fact-based discourse, who do live in an alternative universe of alternative facts. We're sort of stuck with that problem, I think, for some time, but I think the majority of the American public are increasingly on board.

CURWOOD: There's another similarity I'm thinking of regarding the COVID 19 pandemic and climate disruption. And that is the hollowing out of the whole scientific community in the regulatory agencies. I mean, some 45,000 public health workers at all levels of government, whether at the federal or the state or the town, those jobs vanished over the last decade. I'm old enough to remember the you know, the town always had a public health officer, people didn't necessarily like that person, because he was going in and out of restaurants and slapping a "don't eat here", or showing up with a needle or even trying to track down a sexually transmitted disease situation that people were embarrassed about. But my God, we don't have anybody in our communities right now who know what to do to distribute vaccines, do we?

MANN: Yeah, you know, there's a lot of infrastructure that we need to build back. And you know, that's one of the things I like about this administration's motto is the recognition of that: build back better, we've got to build back. I hope they interpret that mandate broadly, right? Because that's not just at the federal level, as you allude to, that penetrates all the way down to the local level. We've, you know, for various reasons, lost so much of this critical infrastructure. And we've seen the cost of not having that infrastructure.

CURWOOD: I have a question that I want to play for you from one of the students at Boston College. And it's a Carli Brenner. And let me ask our producers if they could roll that bit of video.

Part of the Russian government’s interference in the 2016 US Presidential Election is speculated to have ties to fossil fuel interests and climate inaction. At the 2017 G-20 Hamburg Summit, US President Donald Trump (center right) and Russian President Vladimir Putin (center left) met alongside Russia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov (far left), and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson (far right). Rex Tillerson, when he was the CEO of ExxonMobil, represented Exxon’s interests in Russia and was once awarded Russia’s Order of Friendship. (Photo: Kremlin.ru, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

BRENNER: Hi, my name is Carli Brenner. I'm a senior at Boston College, and I'm majoring in political science, with minors in environmental studies and management and leadership. And Dr. Mann, my question for you is about how today, people's beliefs about climate change have become really tied to their individual political identity. So how can we separate climate change from the political realm so that climate action can be seen as a nonpartisan movement rather than a win or a loss for either side of the political spectrum? Thank you.

MANN: Yeah. Thanks so much, Carli, it's a great question. I love the fact that you're sort of combining public policy and environmental studies in your studies, because that intersection is going to be so important moving forward in solving the great problems that we face. And we do need your generation to help solve some of the problems that my generation has created. And I'm confident we will. And part of the solution, I think, as you allude to, is we need to de-politicize science. It's become convenient, unfortunately, for, you know, certain powerful interests to sort of mobilize people against the findings of science. We saw that with COVID-19. And, of course, we've seen that with climate change over an even longer timeframe. I have some hope that we will get past that for a few reasons. I could be wrong. But I think that we had sort of a moment now over the past several years, where we've sort of looked into the abyss. And I don't think collectively, we've liked what we saw, we've seen the death and destruction that results from our unwillingness to listen to what science and what scientists have to say. And so I do think there's a newfound respect, not among all and again, Steve and I were just talking about that: there is this contingent that's sort of been weaponized now by four years of Trumpism. And they're going to be there for some time. And we're gonna need to contend with that. We're not going to win everybody over to the side of fact-based discourse and science-based policy. But I do think that we can put together a winning majority for action on these fronts, and that majority will consist of not just progressives and Democrats, but I think moderate Republicans, moderate conservatives, who do not like the direction that they've seen their party move in. And I think the reaction from that will actually lead them into sort of a more collaborative framework when it comes to working on problems like climate change. Part of the reason I'm optimistic about that is sort of the generational component to this. Obviously, there's the youth climate movement. And that is really inserted in a very profound way, sort of intergenerational ethics into this discussion. And I think that's so important. But there's also just the fact that if you look at polling, I believe it's something like 70% of Republicans under the age of 40, which to me, sounds really young these days.

Michael Mann and Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood in 2019. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: Time flies, Michael, when you're having a good time.

MANN: I know, I know. It sounds so young. So you know, yeah, that is young, under 40. Young republicans. 70% are on board. Climate change is real. It's a problem. We need to do something about it. I think the writing's on the wall. You see some of the same conservative pundits and pollsters, like Frank Luntz, who actually helped Republicans in the fossil fuel industry in their messaging to defeat climate action back sort of in the Clinton era. Well, Frank Luntz is flipped now. He's actually been helping Democrats with their messaging, because he recognizes that this is a real problem. And I think he and his generation of Republicans don't want to be responsible, they don't want to be seen as having been on the wrong side of history with what is arguably the greatest and most important challenge that we face. So for those reasons, and just sort of the new political blood with Biden, his administration and the actions he's already taking, and the prospects for climate action in the US Congress now to complement his executive agenda. All of these reasons make me optimistic, you know, that we will bring more, you know, moderate conservatives into the fold, that there will be this, you know, Coalition for climate action, that will be bipartisan. Some people are going to be left behind, we're not going to win everybody over. But you know, no political movement has ever, you know, had 100% of the public on board, I think we have a very motivated and a very righteous coalition here for action.

CURWOOD: Well, spoiler alert, if we don't all get engaged in this in some level or another, and not in that personal way, because at one point in your book, you talk about how some of the inactivists push people to feel that, well, if you're gonna deal with climate, you need to drive the right car or recycle the right way, that keeping us from looking at collective action. But yeah, we can't do this without collective action. We don't have the power to have charging stations for an electric car. I mean, we don't have the power to change our agricultural system so that they sequester carbon instead of releasing it. We don't have the power to change so many of these things as individuals, but we can collectively.

MANN: Absolutely, Steve, You and I can't block the additional fossil fuel infrastructure. You and I can't take away subsidies for the fossil fuel industry. We can't provide subsidies for renewable energy, we can't put a price on carbon. We need our policymakers to do those things. We can't solve this problem without them, instituting those systemic changes that we ourselves, can't alone. But we can use our voice. And that's what makes me so optimistic. Over the last, you know, several years, we've seen young people using that voice. And we've all used our voice collectively at the polls, to elect politicians. Look, elections have consequences. We have a president who ran on climate, has a mandate on climate, and is now leading on climate, and he's got a Democratic Congress that's going to help him do that. And it wouldn't have happened if this coalition that we talked about hadn't come out and demanded change. And so that's why I'm optimistic. It's late in the game. It's, you know, the fourth quarter, and we're down to touchdown or two. I won't use a Patriots analogy here, I'll resist that temptation. But but the game isn't over. And in fact, the game is very winnable.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann is a professor of atmospheric sciences at Penn State and author of the book, The New Climate War: The Fight to Take Back Our Planet. Our conversation with Professor Mann is part of our ongoing live event series, the Living on Earth Book Club. Our book club meets next on March 11th at 4:30 pm Eastern, and you are invited. We’ll be talking to the daughter of Katherine Johnson, an African American woman who worked as a mathematician for NASA starting in the 1950s. Her work, chronicled in the movie Hidden Figures, helped safely land the first man on the moon at a time when segregation was still law for much of the land. Katherine’s daughter, also named Katherine, worked on a children’s book with her family about her mother’s accomplishments at NASA shortly before her mother passed away. It’s sure to be a thought-provoking conversation so please join us on March 11th at 4:30 pm Eastern. To register go to the Living on Earth website, loe dot org slash events.

Related links:

- Michael Mann’s website

- Learn more about The New Climate War

- Affiliate book link for The New Climate War (Link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Project Trio, “Shir” on Instrumental, by Project Trio, self-published]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Midwestern ginseng farmers are struggling as Asian markets collapse amid the pandemic and trade war with China.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Project Trio, “Shir” on Instrumental, by Project Trio, self-published]

Hard Times for Ginseng Farmers

Will Hsu, left, harvests ginseng with his father Paul on their farm in Marathon County, Wisconsin. (Photo: Courtesy of Hsu Ginseng Enterprises)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

American ginseng farmers have been hit hard by the pandemic and the ongoing trade war with China. Ginseng is a knobbly, bitter root that’s been used in traditional Chinese medicine for centuries. And Native Americans also have a long history of using wild American ginseng, which once grew widely in the Appalachian region before it was overharvested in the 19th century. Ginseng may help boost the immune system, lower blood sugar and improve focus, although the U.S. Food and Drug Administration says there’s not enough evidence to back up these claims. A single county in Wisconsin, Marathon County, produces about 95% of the total crop in this country, most of which was exported to Asia before the Trump administration started the trade war with China. Our recent intern Aaron Mok wrote about the growing crisis for ginseng farmers in Civil Eats and joins me now. Hey, Aaron how’s it going?

MOK: Good Bobby, how are you?

BASCOMB: Good! Your article follows the story of a family farm that's been growing ginseng for four generations. It's the Heil family. What is their relationship with ginseng? How did they come about being ginseng farmers and what does that mean in this region?

MOK: Yeah, so I spoke to Joe Heil, he's been a ginseng farmer in Wisconsin for 25 years. He's a fourth-generation ginseng farmer. Ginseng is his livelihood; he runs a thriving ginseng business, or what used to be thriving before the pandemic and the trade wars. He has around a thousand acres of land, which is probably the most land that most ginseng farmers have in the county. So he's been very successful in his business.

BASCOMB: But you say that they're struggling today. Why is that? Let's talk first about the pandemic. How has that impacted their business?

Fourth-generation ginseng farmer Joe Heil inspects American ginseng seeds, at his farm, also in Marathon County, Wisconsin. (Photo: Courtesy of Heil Ginseng Farms)

MOK: Yeah, so the pandemic was a huge blow to Heil's business as well as the ginseng business in general. The American ginseng industry is export-heavy; 95% of the ginseng revenue sales comes from exports to East Asia. And because of the pandemic, there are travel restrictions between China and the US. And during harvest season, Chinese consumers would travel to Wisconsin to inspect the ginseng, to look at it, and to bring it back for their families. But because of travel restrictions, they're not able to do that. So revenue has decreased a lot as a result.

BASCOMB: And the trade war with China is also taking a toll from what I understand. What's going on there?

MOK: Yeah, so that's when the ginseng industry began to suffer. Before the trade war started in 2018, the industry was making between $50 and $70 million a year. But since the trade war started, and since the pandemic devastated the industry, ginseng farmers only make around $10 to $15 million a year. Ginseng prices went from $50 a pound to $20 a pound. So that's almost, yeah, like less than half of how much they were making at the beginning before the trade wars.

BASCOMB: So I would guess that these farmers now have a surplus of ginseng on their hands if they can't sell it and they're not getting a good price for it. Maybe they'll just hold on to it for now.

MOK: Yeah, that's what the farmers are doing. They do have an excess supply of ginseng that they're holding on to. Luckily ginseng, you can harvest and it'll last for a while. But they do have an excess supply and no demand.

BASCOMB: And you write in your articles that a rise in anti-Asian rhetoric amid the pandemic, or as President Trump called it, the "China virus," is also a problem for these farmers. Can you tell us more about that, please?

Ginseng cultivation at Heil Ginseng Farms (Photo: Courtesy of Heil Ginseng Farms)

MOK: Yeah, so I talked to Will Hsu, he is the president of Hsu Ginseng Enterprises. It's one of the biggest American ginseng enterprises in Wisconsin as well as the US. He is Chinese -- he comes from a Taiwanese background. And according to him, once the trade wars hit, Hsu's Ginseng Enterprises had to change their business model. So originally, their main revenue was coming from ginseng exports to China. But now their main revenue comes from selling ginseng domestically. And domestic-sold ginseng goes to Chinese pharmacies, traditional Chinese medicine shops, and Asian grocery stores. But because of the pandemic and because of Trump calling coronavirus, the "China virus," Hsu believes that consumers are not willing to purchase any products by Chinese communities because they're afraid to catch the virus. And that has, Hsu believes, decreased their revenue. He unfortunately doesn't see any recovery in the near future. In his words, the industry has faced punches after punches, and the future of the ginseng industry is unclear to him.

BASCOMB: Aaron Mok is a freelance reporter for Civil Eats. Aaron, thanks so much for taking this time with me today.

MOK: Thank you, Bobby.

BASCOMB: By the way, with his hands full amid the pandemic President Biden so far appears to be in no hurry to end the trade war with China.

Related links:

- Read Aaron Mok’s Civil Eats article on the struggling ginseng industry

- Mount Sinai: Preliminary research on ginseng and your health

- Undark | “In Appalachia, a Plan to Save Wild Ginseng”

[MUSIC: The Silk Road Ensemble, feat. Bill Frisell, “If You Shall Return” on Sing Me Home, by Sandeep Das/Hu Jianbing/Kojiro Umezaki, Masterworks (Sony Music Entertainment)]

Beyond the Headlines

There are only an estimated 104,700 Bornean orangutans remaining, due to habitat loss, expansion of palm oil plantations, and poaching. (Photo: Bernard Dupont, Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Centre, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, let's see what's going on beyond the headlines now. And of course, to do that we turn to Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. On the line now from Atlanta, hey there, Peter, how are you doing and what have you got for us?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. There's a story that is the nexus between the COVID pandemic and an environmental crisis in Indonesia, where rescued orangutans are being returned to the wild, despite of COVID risk because they're so similar in DNA to humans.

CURWOOD: Yeah that's right. I mean, a lot of zoonotic diseases, I'm thinking of HIV, for example, are found in the primates. But wait, these are rescued orangutans, so what's the problem?

DYKSTRA: Groups like the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation are looking to repopulate the wild. Bornean orangutans are down to about 100,000, that's a fraction of their original population. Palm oil plantations, other farms, wildfires, poaching are all claiming orangutan populations. COVID is a new threat, and in order to guard orangutans from too much human contact, instead of driving the orangutans about three days into the jungle, they're bringing them in by helicopter.

CURWOOD: Well, this is good news. I'm glad to see orangutans getting a chopper ride to avoid getting COVID and actually probably then spreading it among other orangutans once they got back into the wild. Hey, what else do you have for us today, Peter?

Researchers found that glyphosate, one of the most widely used pesticides, increases soil erosion and is linked to the release of chlordecone, stored in the soils of banana plantations in Guadeloupe and Martinique. (Photo: Duleeka W Knipe, Researchgate, CC BY 4.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, glyphosate has been much in the news, a lot of lawsuits, judgments for millions, if not billions of dollars from people who say they've been made sick from glyphosate, now the most common weed killer anywhere in the world. There's a study coming out of the West Indies, that suggests a problem we weren't aware of. That glyphosate use on banana plantations could be releasing an old banned pesticide into the environment.

CURWOOD: Well wait, how's that supposed to happen? I mean, a new chemical releases an old one? How do you do that?

DYKSTRA: Well, glyphosate is essentially a defoliant, it takes down all sorts of vegetation. When that vegetation leaves and the soil is exposed, the erosion takes place. And in that erosion, old residues of a chemical called chlordecone, a probable carcinogen, is released into the waters and the land in places like Guadeloupe and Martinique in the West Indies.

CURWOOD: Okay, so they call things like chlordecone a persistent organic pollutant and I guess it was locked up in the soil there until the use of glyphosate started the erosion. How big a deal is this, Peter?

DYKSTRA: It stays dangerous for a long time, and we don't know exactly how big a deal is it. There are suggestions that it's found in other crops in Europe. They're just beginning to look for it. Although the chemical chlordecone is also known by another name, kepone. It's a likely carcinogen, it was outlawed in the US in the 1970s. Some folks may remember a major kepone spill in the James River, were not only a stretch of miles and miles of that historic river were polluted, but about a hundred factory workers were made sick by kepone pollution.

CURWOOD: Hey, what do you have from the history books for us this week?

The Exxon Valdez oil spill was one of the most devastating oil spills to date; 11 million gallons of crude oil spilled into the Prince William Sound. It is estimated that 55 tons of remaining oil still oozes out from underneath the beach, more than 30 years after the spill. (Photo: ARLIS Reference, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, thirty years ago next week, a federal court rewarded a huge payout for Alaska fishermen, and others whose livelihoods were damaged by the Exxon Valdez oil spill. That was two years after the 1989 spill. The initial judgment was for about 5 billion. Exxon spent two decades and a lot of lawyers' money, appealing it down. The punitive damages were eventually knocked down to just over half a billion that was split between 32,000 plaintiffs: individuals, companies, governments, and of course their lawyers. But the payouts didn't happen until 2008, nineteen years after the spill, by which time 20% of the original plaintiffs had died.

CURWOOD: Boy, what a case study of that old aphorism "justice delayed is justice denied." Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk again next week.

After a two-decades long legal battle, Exxon was ordered to pay only 507 million dollars to the 32,000 plaintiffs for the oil spill, instead of the initial court order of 5 billion dollars. (Photo: Michael Poche, U.S. National Archives, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website, that's loe.org.

Related links:

- EcoWatch | “Rescued Orangutans Are Returned to Indonesia Wild Amid COVID-19 Risk”

- Reuters | “Ten Rescued Orangutans Returned to the Wild in Indonesia”

- Chemical & Energy News | “Glyphosate Weed Killer Releases a Banned Pesticide into Islands’ Waters Through Soil Erosion”

- The Seattle Times | “Exxon Valdez Victims Finally Getting Payout”

- CBS News | “Exxon Valdez Oil Spill: 20 Years Later”

[MUSIC: Charanga Cakewalk, “Melodica” on Chicano Zen, by Charanga Cakewalk, TriLoka/Artemis Records]

Nature and the Beat

A Beast Box Orangutan and a Bornean Orangutan. (Image: Russell

[Sfx gibbon howling]

BASCOMB: Those Orangutans in Borneo share habitat with their smaller primate cousins, the gibbons, whose howling calls can travel up to two miles across the dense rainforests. Many animals make some sort of sound to find a mate, warn of predators, or claim and defend their territory. And now their sounds can be used to create music from your home as a fun diversion for all ages during this year-long pandemic.

[SFX KATYDID]

BASCOMB: For many of us the staccato notes of a katydid might conjure up memories of a warm summer night, but for Ben Mirin a katydid’s chirp is music.

MIRIN: I hear music in everything.

BASCOMB: Ben calls himself a Wildlife DJ. He travels the world as a National Geographic explorer to record animal sounds. And with help from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ben created a website called Beast Box where users can layer animal sounds over a beat to create their own compositions.

MIRIN: I’m just a messenger for the intricately tuned voices of the natural world. And the fact that nature is always singing is something that is really exciting to me and I hope can create similar excitement and joy others.

BASCOMB: To make a song users open the website and then choose one of 7 beat tracks that Mirin created himself. You can choose - say Great Barrier Reef beat…

[SOUND – GREAT BARRIER REEF BEAT]

BASCOMB: Or Sonoran Desert Beat…

A Beast Box Cicada. (Image: Beast Box)

[SONORAN DESERT BEAT IN CLEAR]

BASCOMB: Then select an animal sound, there are 30 of them. You can add as many as five at a time to create a song. So, let’s say you choose a coyote….

[CALLS OF COYOTE IN CLEAR OVER BEAT]

BASCOMB: Then an eastern whip-poor-will …

[MUSIC ADDING WHIP-POOR-WILL]

BASCOMB: A parrot fish …

[MUSIC ADDING PARROT FISH]

BASCOMB: A Hadada Ibis …

[MUSIC WITH ADDED IBIS OVER BEAT]

BASCOMB: And lastly a Blue Wildebeest.

[MUSIC WITH ADDED WILDEBEEST OVER BEAT]

BASCOMB: Put them all together and your song is complete.

[MUSIC PLAYS, THEN FADES TO BED]

BASCOMB: On the website there is a paragraph description of each animal and an explanation of their habitat. Each time a user chooses an animal musician, a graphic of that creature pops up on the screen and dances to the beat. For instance, there’s an orangutan in a red leather jacket and matching sunglasses.

[CALLS OF ORANGUTAN WITH BEAT BACKING]

BASCOMB: And a tropical Boubou wears a gold chain and a red cap.

[CALLS OF BOUBOU WITH BEATS]

BASCOMB: Mirin hopes beast box will be fun for anyone but the graphics and the genre of music are geared towards kids like 12 year old Orion Brown. Orion says he likes playing with the website.

A Bornean Gibbon. (Image: Beast Box)

BROWN: I think it’s pretty cool. It’s a way to get a good education but also have some fun.

BASCOMB: For an additional challenge, users can try to put all of the animals from the same ecosystem together with the beat designed for that environment – it’s called Beast Mode. Orion chooses the Madagascar Rainforest.

[BEATS OF MADAGASCAR RAINFOREST, PLAYS AS BED]

BROWN: The first animal in that ecosystem is the Indri.

BASCOMB: Neither of us know what an Indri is. So Orion reads the description -- turns out they’re lemurs.

BROWN: A small group of Indri wake up in the treetops and begin their morning shout outs. Indri are large for lemurs with booming voices amplified by enlarged throat pouches.

[INDRI CALLS ADDED]

BASCOMB: Alright, what’s next in the Madagascar rainforest?

BROWN: The next one is the Lesser Vassa Parrot.

[PARROT CALLS ADDED]

A Blue Wildebeest. (Image: Beast Box)

BASCOMB: He finishes up with the Madagascar Long Eared Owl, the Red Fronted Coua, and the Souimanga Sunbird.

[“BEAST MODE” THEN SONG PLAYS AND FADES TO BED]

BASCOMB: So what do you think of the song you made?

BROWN: I think when you mash them up with all the ecosystems together, it sounds better, almost like it’s sort of made for the beat.

BASCOMB: So, you mean when you have all of the same ecosystem, like all of the desert or the rainforest or so together?

BROWN: Yeah.

BASCOMB: Do you think that maybe they evolved and they lived together in the same forest and making music together it comes kind of naturally. What do you think of that idea?

ORION: I think that would be a possibility and if so that would be super cool.

BASCOMB: Ben Mirin says that Orion is on to something, thinking that the different animal voices complement each other.

MIRIN: Yeah, I would agree with his observation. Animal voices have evolved over millions of years to occupy different acoustic niches in an ecosystem so they don’t compete with one another.

BASCOMB: Making yourself heard is critical to surviving in nature. That’s how whales find mates across the ocean and coyotes defend their territory in the desert. Animals living in the same environment are already tuned to work well together so everyone can be heard and Mirin is excited about tapping into that existing symphony of sounds.

MIRIN: As a producer that means my instruments are already mixed. So instead of being a solo musician I get to be a messenger for the finely tuned orchestras of the natural world.

National Geographic Explorer and wildlife DJ Ben Mirin. (Photo: Drew Fulton)

BASCOMB: Mirin says what he wants is for Beast Box to help people learn about nature and create a connection with the natural world.

MIRIN: At the end of the day understanding and connecting with nature is critical to falling in love with it and we can’t save what we don’t love. So, I would hope that this opens a pathway for you to find your own sense of connection and love for nature so that you can be inspired to protect it because this is a collective future we all share.

BASCOMB: And there’s much more about Ben Mirin and his Beast Box on the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Beast Box

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- About Ben Mirin

[MUSIC: Izabella Effenberg, “Crystal Silence 1” on Crystal Silence - Music for Array Mbira, by Izabella Effenberg, Unit (Membran)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Grace Callahan, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Paige Greenfield, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Natalie Seo, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb. And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth