Ecological Conversion and Solidarity

Air Date: Week of April 23, 2021

“This is who you are”: In the Lakota language of Tiokasin Ghosthorse’s people, the word for water is “mni” and also conveys the idea of “the living relationship between you and I and all things.” (Photo: Linus Nylund, Unsplash)

Science and policy are vital in building a more sustainable world, but they often don’t convey the values we need in order to engage people to do so. With spiritual guides who carry diverse traditions and teachings, Host Steve Curwood surveys the values that can guide us along this path towards ecological harmony. Indigenous stories, holy scriptures, East Asian cosmologies, papal encyclicals and divine revelation all shed light on our duties and relationship to each other and to our common home.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: The Gaia hypothesis is a fairly recent take on cosmology that science is coming to respect more and more, but many ancient societies and religious traditions have long shaped our values based on being a part of, and not apart from the lives we share on this planet.

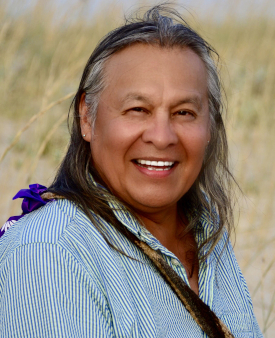

GHOSTHORSE: My name is Tiokasin Ghosthorse, and I am from the Cheyenne River Lakota reservation in South Dakota.

When I was four, my father had passed away. And I had spent the days in the summer along a small creek. And it was very warm, the sun was coming down, it was about noon, and I was watching the water and the crows and woodpeckers play, in their reflections. And I was sitting there, and I probably was thinking about my father, I don't remember but I felt a little sad. I heard some crunching of rocks on the ground, I looked behind me and at a distance around the bend of a creek came an old man. And this old man I've never seen before, but he had raggedy leggings on, and moccasins, and they were leather.

Tiokasin Ghosthorse is a member of the Cheyenne River Lakota Nation of South Dakota (Photo: Courtesy of Tiokasin Ghosthorse)

And he stood there, and I wasn't afraid of him for some reason. And he reached down, and he grabbed some dirt, some Earth, and he threw it out over the water, and it sprinkled, and you know how stones and pebbles hit the Earth -- there's small circles everywhere. And he said, this is who you are. And I was amazed and in that time construct of a young person four years old, you were looking at all the the circles and then you looked up, I looked up and I didn't see him, and he was not there.

CURWOOD: That mystifying experience stuck with Tiokasin. Later, he came to understand better what it meant.

GHOSTHORSE: So in life, I wanted to know what that that magic to me was, and it was basically water. And in the Lakota definition, "Mni", is the “m” means something like that which is related between you and I and all things. And “ni” is living, or life; and the “i” is voicing. So voicing the living relationship between you and I, and all things is what we call water. And water has consciousness.

CURWOOD: In the English language, we don’t quite have the words to convey what he is saying. But essentially, to the Lakota, water is more than the physical substance we splash on our faces in the morning, or use to slake our thirst. It is a way to define how we as individual people are connected to all of life.

GHOSTHORSE: You heard it out of Standing Rock: they were saying Water is life. "Mni wiconi”: water is life.

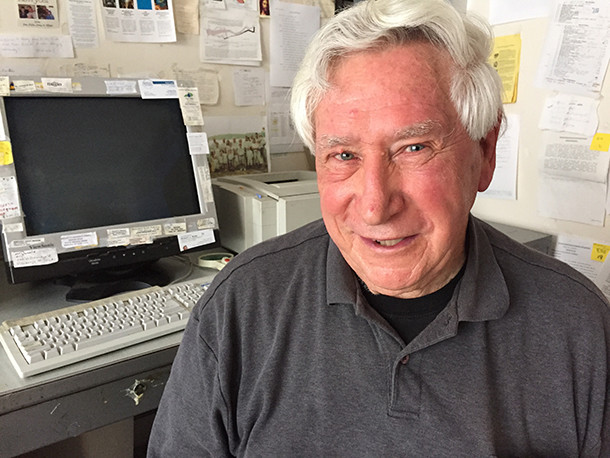

Joe Bruchac is Nulhegan Abenaki elder, a storyteller and author of more than 120 books for children and adults. (Photo: Courtesy of Joe Bruchac)

CURWOOD: But in many ways our current economic and political system lacks protection for our water and natural resources, which are essential for the health of the planet and humankind. And Native American beliefs like the Seven Generations Principle are counter to the destructive tendencies in our current systems that value transactions, short-term gains and efficiency over resiliency. Joe Bruchac is a writer and storyteller of the Nulhegan Abenaki Nation and sees this concept as a guideline for a better world.

BRUCHAC: We must think in terms of seven generations, what will happen seven generations from now, if I do this. And that goes way beyond ideas of investment, way beyond ideas of contemporary short-term politics, it becomes an investment in a future that is sustainable, that idea of seven generations is something central to my heart, and to the hearts of most people who live a traditional native way.

CURWOOD: People from other spiritual traditions are making similar connections. Rabbi Yonatan Neril, who directs the Interfaith Center for Sustainable Development in Jerusalem is one.

RABBI NERIL: The ecological crisis is not a crisis of the birds and the bees or the trees and the toads. It's a crisis of how we live as spiritual beings in a physical reality.

Rabbi Yonatan Neril founded and directs the Interfaith Center for Sustainable Development in Jerusalem. (Photo: Courtesy of Rabbi Yonatan Neril)

CURWOOD: He says spiritual leaders who see the ecological crisis through this lens find faith and hope in a variety of sacred texts.

RABBI NERIL: The teachings in, whether in the Bible or the Quran, or the Bhagavad Gita for Hindus, all sacred texts contain deep teachings about ecological sustainability. For one, the great spiritual masters of previous generations were living much closer to nature than the average human being is today.

CURWOOD: And today’s spiritual leaders are seeing that distance from nature, and the climate emergency, and calling their congregants to act. Pope Francis wrote Laudato Si’: the encyclical on climate change in 2015, which is a call for Catholics and non-Catholics alike to undergo an ecological conversion and care for our common home.

He writes, “Our planet is a mother for all of us. We must hand it on to our children, cared for and improved, because it’s a loan they make to us”. Pope Francis is famous for living simply in the Vatican and traveling in a small, unostentatious vehicle, the Kia Soul. Christiana Peppard is a professor of Theology at Fordham University and sees Laudato Si' in the canon of the followers of Saint Francis of Assisi, who dedicated his life to the poor, the animals and the environment.

Pope Francis spoke to the U.S. Congress in September 2015 about climate and other issues while thousands of climate activists rallied on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. (Photo: Stephen Melkisethian, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

PEPPARD: I think the Pope sees a lot of the dynamics of environmental degradation globally as driven by economic structures of profit, and a focus on economic development and growth that is not accountable to the limitations of what the planet can absorb, and it is not accountable to the burdens that are carried by people living in poverty.

CURWOOD: Like Pope Francis Father Albert Fritsch is a Jesuit priest who was trained in chemistry. The pope earned a master’s degree in chemistry and Father Albert a PhD in chemistry before either were ordained. Father Albert went on to co-found the Center for Science in the Public Interest in Washington and a related organization in Appalachia where he is now a parish priest and director of the website Earth Healing. There’s a very personal element to his environmental work. Asked if he had ever felt Jesus Christ speak directly to him, he told the story of visiting the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem which houses the rock where the body of Jesus was laid after he was taken down from the cross. There is a hole in the display case covering the rock:

Father Albert Fritsch is director of Earth Healing, a website dedicated to providing daily reflections on simple living and matters of faith. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

FRITSCH: And so I reached into the hole. And when I did, it was a voice came saying, “Look what they've done to my earth”. And it came as clearly as anything I've ever heard in my life. And so, when you asked me, What would Christ say? I said, I heard the voice of Christ. And it said it with tremendous sorrow, and difficulty because he thinks so much of his Earth: “look what they've done to my earth.” It changed my life. I never, I wasn't the same after that. But I feel that Christ was telling me that the Earth itself has been damaged, and that it hurts him very badly.

CURWOOD: From then on Father Albert devoted his work to caring for the environment. Islam also has much to say about ecology.

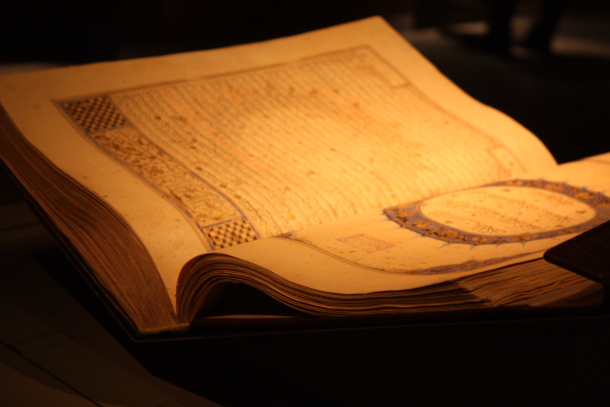

KHALID: Nearly almost every page as in seven, eight times out of ten you you turn the Quran randomly and you will get a sentence of a verse or a reference to the clouds, the sky, the birds, the bees, the trees, and creation and so on and so on.

CURWOOD: Professor Fazlun Khalid, is a theologian and Founder-Director of the Islamic Foundation for Ecology and Environmental Science.

KHALID: So, the Quran, I would say is an environmental manual. You see when the Quran talks about [Speaking Arabic], you see the Najm (star) and the shadows, the plants and the trees bow in adoration to Allah. And Allah says, then I created [Speaking Arabic] he says I created the world in balance.

The Qu’ran is filled with passages relating to the environment as the creation of God and highlights why humans must protect the earth. (Photo: Riyaad Minty, Flickr, CC BY-NC-2.0)

CURWOOD: In fact, this idea is at the very heart of some East Asian ways of thought.

Mary Evelyn Tucker is the co-founder and co-director of the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology.

TUCKER: Confucianism has a very rich cosmology, of continuity of being, of interdependence, and it's very specific: of cosmos, earth, and human. That's their Trinity, that’s their triad. We humans complete the triad of cosmos and earth. And we are co-creators with what they speak of as the transforming and nourishing powers of heaven and earth.

CURWOOD: Mary Evelyn Tucker explains that Lao Tzu is the progenitor of Daoism, with its values that include simplicity, humility and living in harmony.

A hanging scroll depicting Confucius, Lao-Tzu and a Buddhist Arhat. (Image: 丁云鹏 (Ding Yunpeng), Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

TUCKER: Lao Tzu would say, we have to go with the flow, we've got to understand the power of water to carve out the Grand Canyon. We've got to understand that which is passive, hidden, dark, mysterious and yet generative of life and transformation. This is an extraordinary contribution to human thinking, nature's ways.

CURWOOD: So, from Lao Tzu and Daoism we have this idea of resonance with nature. Confucianism takes that a step further.

TUCKER: There’s a practical dimension to Confucianism. It says, that’s necessary but not sufficient, going with the flow. Because we also have to recognize human agency is critical. And if we don't align ourselves with these processes to create political systems, educational systems, and social systems for the common good, it will just be a personal transformation, that will feel good.

CURWOOD: What we choose to do, or fail to do, affects everyone around us. Rabbi Yonatan Neril speaks about self-interest and the climate.

RABBI NERIL: So there's a teaching from Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, who lived about 2000 years ago, in the north of Israel during Roman times. And he talks about somebody who goes onto a ship and starts drilling underneath his or her own seat, and the other people on the ship, say to the person, what are you doing? How could, how can you drill underneath your own seat? And the person says, Well, I'm doing whatever I want, because here's my ticket, and this is my seat, and I can do whatever I want. And the other people say to that person, well, no, you can't, because what you're doing impacts us. So, I think that this teaching has relevance for the climate crisis. Because each human being today, or most people, most of the 8 billion people alive today, are drilling underneath the collective ship of planet Earth. And similarly, on that ship, this person may not have been psychotic or crazy, this person may have just been trying to fish because they were hungry or get some fresh water because they were thirsty or put their feet on in the water because their feet were hot, the person may have been rational. And so too each of us is acting rationally, but but collectively, what we're doing is crazy, because we want the next generation to inherit a livable planet. But if we act with more spiritual awareness and engage in long term thinking, and care about other people and creatures, then we will actually be able to have a ship that is sustainable and seaworthy and can continue for many generations.

Mary Evelyn Tucker says, “Lao Tzu would say, we have to go with the flow, we’ve got to understand the power of water to carve out the Grand Canyon.” (Photo: Alan Carrillo, Unsplash)

CURWOOD: Stories from ancient traditions highlight this very idea: that we are not alone on the earth and our actions transcend through time. When Native American Joe Bruchac visited the jungles of the Mexican state of Chiapas, he spoke with Chon King Viejo an elder of the Lacandon Mayan people.

BRUCHAC: Chon King said, and I love this, though it's scary. He said, first of all, every time you cut a great tree in the forest, a star falls from the sky. So, before you cut a tree, you must ask the guardian of the tree, the guardian of the star, if what you're doing is correct. And he said, if we cut down all the trees of the forest, then the gods of diseases will come out of the forest and come among the people. He also said, if we cut all the trees, a great darkness will come upon the world. And in that darkness, you will hear the growl of the jaguar and you will be afraid. And so, if we do not maintain that balance, we are going to be experiencing that jaguars growl. That great darkness. So, to me, having traveled at some of the world, having met some of the people whose indigenous traditions I found so meaningful and similar to my own. I have to say that we all live on the same Earth, that our original teachings are very much the same. If we look to their relationship of us with our mother planet.

CURWOOD: It’s not easy to think that long-term, and we sometimes fall into the trap of thinking that we can engineer our way out of our problems and into the future. That’s only part of it. As we conclude, here are some voices, starting with Mary Evelyn Tucker.

Mary Evelyn Tucker co-founded and co-directs the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology alongside her husband, John Grim. (Photo: Courtesy of Mary Evelyn Tucker)

TUCKER: We've got a lot of the science and technology and economics and policy. But we don't necessarily have this deep, inner, spiritual sensibility that we can make it through this bottleneck of extinction, and climate emergency and so on. So, the human spirit needs care and activation on every level, I think.

RABBI NERIL: Over the past 12 years, I've been involved in interfaith environmental work. And I have the privilege of working with amazing people, priests, pastors, Imams, Swamis, monks, who care deeply about ecological sustainability and are approaching it from their different religious traditions. So, you know, it's a commonality, it's, and that's, you know, if we're on a, we're on this ship together. And and so the most important thing is that we learn to live here sustainably together.

CURWOOD: That was Rabbi Neril, and finally, Mamphele Ramphele is a South African physician, activist and widow of Steve Biko. She says our gifts of today are bright possibilities.

RAMPHELE: And so we now have an opportunity to reimagine a world where we see ourselves as part of nature. We are not saving nature; nature will save itself. We have to save ourselves from this existential crisis by changing fundamentally the way we live, how we relate to one another, and how we relate to the rest of life. And that's the opportunity we have.

Links

Read the Encyclical Letter Laudato Si’ of the Holy Father Francis on Care of Our Common Home

Learn More about writer and storyteller Joseph Bruchac

Learn more about Mary Evelyn Tucker and the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology

About Rabbi Yonatan Neril and the Interfaith Center for Sustainable Development

Learn more about Father Albert Fritsch’s website, Earth Healing

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth