April 23, 2021

Air Date: April 23, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Greening the Economy

View the page for this story

As we celebrate Living on Earth's 30th year on the air, we're offering an Earth Day special that examines this decisive moment for the human species and our challenging relationship with our planet. Host Steve Curwood starts by meeting people who envision a future reshaped by an emerging energy system and new power structures, as we wean off of fossil fuels. (14:35)

A Living Earth Called “Gaia”

View the page for this story

Next, Host Steve Curwood and the Living on Earth team explore Earth as a complex and self-sustaining organism called Gaia. Over billions of years life has interacted with the air, water and rocks of this planet to keep life in the sweet spots for temperature and resource supplies. With the help of scientists, deep ecologists, children, an astronaut and more, we explore our place on this living planet. (18:13)

Ecological Conversion and Solidarity

View the page for this story

Science and policy are vital in building a more sustainable world, but they often don’t convey the values we need in order to engage people to do so. With spiritual guides who carry diverse traditions and teachings, Host Steve Curwood surveys the values that can guide us along this path towards ecological harmony. Indigenous stories, holy scriptures, East Asian cosmologies, papal encyclicals and divine revelation all shed light on our duties and relationship to each other and to our common home. (15:27)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

210423 Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

On this Earth Day in the climate crisis we are looking forward to how the world is reimagining a greener economy.

WILKINSON: The care economy is largely a green economy. It's largely a low carbon set of industries. Interestingly, predominantly held by women, and women of color.

CURWOOD: Also the values solution to the climate crisis.

RAMPHELE: We have to save ourselves from this existential crisis by changing fundamentally the way we live, how we relate to one another, and how we relate to the rest of life.

RABBI NERIL: The ecological crisis is not a crisis of the birds and the bees or the trees and the toads. It's a crisis of how we live as spiritual beings in a physical reality.

CURWOOD: That’s this week on Living on Earth, stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Greening the Economy

Protesters at a rally in Oakland cite the economy as a focus of climate activism. (Photo: Lily Rhoads, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: Miles Davis “Milestones” on Milestone, Sony Music Entertainment Inc.]

CURWOOD: Earth Day 2021 marks an important milestone for Living on Earth. In April of 1991 Living on Earth started broadcasting weekly on public radio, and for these past 30 years we’ve been hitting the airwaves ever since. Biologist and Woods Hole Research Center founder George Woodwell helped inspire me to start this show when he told me that global warming from burning fossil fuels and forests would likely melt the Arctic. He explained that as the permafrost released its CO2 and methane, those added greenhouse gases would cause more warming and melt the arctic even more, which would add yet more carbon to the atmosphere. At some point these self-reinforcing reactions, this feedback loop, would be beyond human control.

[MUSIC: Miles Davis “Milestones” on Milestone, Sony Music Entertainment Inc.]

CURWOOD: As a journalist it seemed to me that if what George described was allowed to get out of hand, little else would matter much for society. So I decided that climate change and so many other environmental stories needed reporting, and here we are. Now many things have changed since 1991 and science has made some amazing advances. The human genome was sequenced, and gene therapy began. The Hubble telescope gave us fantastic views of deep space. Technology gave us the world wide web, which made e-commerce, Google and Facebook possible, and the invention of the smart phone put the world in our pocket. And in politics and society, South Africa ended apartheid and freed Mandela and the US elected its first president of direct African descent, Barack Obama. But the numbers show we are still failing to preserve the climate. Over the last 30 years human-caused emissions have increased by 60 percent. Today the atmosphere holds the equivalent of about 500 parts per million of CO2. That is not good news. We began the industrial age in 1760 with concentrations of CO2 at about half those levels and we are now living through the hottest decade in modern human history. As a result we are seeing record breaking heat waves and wildfires from California to Siberia, floods, rising sea levels and shrinking Arctic sea ice. Not to mention, record-breaking Atlantic hurricane seasons, searing droughts and massive tornado clusters. And all this climate disruption is a result of just a single degree centigrade rise in average earth surface temperatures since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. But our broadcast today is not simply a look back or lament. We are also looking ahead, to shine a light on some possibilities to head off climate disruption before civilization as we know it becomes untenable. We will consider the possibilities of economics, politics, applied science and technology to address climate disruption, though so far they have fallen short. So, we will look to see what they may be missing. And since we humans have caused the climate emergency, we’ll also consider how we can think differently about our place on this planet. For some clues we’ll look to some ancient wisdoms and contemporary anthropology.

[MUSIC: Brian Rolland’s “Along the Amazon” on Dreams of Brazil, On The Full Moon Productions]

CURWOOD: Correlation doesn’t necessarily mean causation, but there are two striking trends that run parallel to the alarming rise in global warming gases. One is the astonishing growth of economic wealth, and in recent years that increase in wealth in the US has been confined to the very richest. In fact, most families in the US have seen little or no gain, with many losing economic power, as many young adults today can’t afford to buy homes like the ones they grew up in. The other trend is the loss of confidence in government action at the national and local levels and the failure of international rules governing climate change emissions to go beyond the honor system. The concentration of economic and political power related to those trends has historically thrived on the extraction and burning of fossil resources. Climate policy critics including Van Jones, Kristina Karlsson and Bill McKibben say that has to change, if we are to halt our present march toward climate Armageddon.

Kristina Karlsson is a program manager for the climate and economic transformation team at the Roosevelt Institute. (Photo: Courtesy of Kristina Karlsson)

JONES: The first industrial revolution hurt the people and the planet, too. —the next industrial revolution has to help the people and the planet.

KARLSSON: Meaningfully addressing climate requires an economic transformation in basically all corners of our economy

MCKIBBEN: I think we’re reaching a turning point. I think that the political power of the fossil fuel industry has begun to wane after a century or two of waxing. And our job is to accelerate that to push hard for really rapid, rapid change.

CURWOOD: There are plenty of ideas about how to preserve a livable climate. And the conventional answer so far has been to double down on approaches that have yet to work, including unproven technology. To save us many advocates say we need market-based solutions such as pricing carbon and technologies such as renewable electricity from solar, wind and other clean energy sources to power our lives. They say we just need to update the systems of the Industrial Revolution that relied on abundant fossil fuels:

GROSS: We had all this energy available, a huge quantity that had never been available before. And that allowed just a complete revolution in the world: revolutions of transportation and manufacturing, all kinds of things that we just never been able to do before.

CURWOOD: Samantha Gross was a senior climate and energy official for the Obama Administration. Now at the Brookings Institution, she notes that by the twentieth century, oil had become the most valuable commodity on world markets.

GROSS: If you were to design a fuel to be used for transportation, you really couldn't do a lot better. It's very energy dense, it has a lot of energy within it for its weight and its size. It's easily transportable. It's a liquid, so it works in an internal combustion engine. It's really an excellent transportation fuel.

CURWOOD: So, she calls for new technologies to power the world while avoiding more climate disruption.

GROSS: We absolutely need both cleaner energy and more energy. There's roughly a billion people in the world right now who don't have access to modern energy services. And so, dealing with climate change, while not providing those people with a better standard of living is no solution at all.

CURWOOD: When climate change first hit the headlines the fossil fuel industry and pushed back on the perceived threats to their profits. Some fossil fuel companies spent millions on disinformation campaigns to stoke climate denial. But now as climate dangers can no longer be ignored and the world is going greener, big capital is excited about new prospects for growth.

WINSTON: We're talking about what many would say is probably the largest new economic opportunity, right?

Andrew Winston is a sustainability consultant for major corporations and co-author of the 2006 book, Green to Gold. (Photo: Courtesy of Andrew Winston)

CURWOOD: Andrew Winston is a sustainability consultant for major corporations and co-author of the 2006 book, Green to Gold, which became popular among fortune 500 executives.

WINSTON: In the past and the 90s 2000s. It's the internet, it's, you know, the growth of connection and mobile. Now, it's the clean economy. And you know, I think we're talking many, many trillions of dollars of market in, you know, transportation in different kinds of fuels and building efficiencies in regenerative agriculture, I mean, just the whole range of things that are in multi trillion-dollar markets. So, the companies that take advantage of that, just like, you know, any former kind of industrial revolution, we've had any of the major Waves of Change, the companies that are prepared for it, and conserve that future, do very well, and the ones that don't, and kind of stick to how they've done things forever disappear.

CURWOOD: But even with the advent of electric cars like the Tesla and pricing of solar power well below that of coal, the growing profits of green tech have yet to halt the climate emergency. More is needed, says Kristina Karlsson, program manager for the climate and economic transformation team at the Roosevelt Institute.

KARLSSON: The markets will have to be a part of this, we can't do this without private money. But focusing on those types of mechanisms alone will not get us anywhere near where we need to be in terms of mitigating climate, and it will also further deepen the unequal structurally racist outcomes that that system has already created.

CURWOOD: She says systemic racism has distorted government policies and spending when it comes to environmental justice and climate justice at home and abroad.

KARLSSON: All fiscal policy, even if it seems completely unrelated to climate will have climate implications. So, it's, it's really a framing argument and a sort of a policy development principle that saying, you can't, you can't ever be climate blind as you're making choices.

CURWOOD: And Kristina Karlsson adds that if human rights and fairness guide the conduct of governments and businesses it would have a more positive economic impact in the long run than self-centered free market approaches.

KARLSSON: Climate is already an economic cost and an economic drag on our economy. Not only are we actually spending money to mitigate climate disaster that's happening now. But we're also seeding risk in our financial system by not dealing with the issue that we all rely on fossil fuels, you know, so we are actively paying for inaction. And as the more we put it off, the more these economic costs are going to compound over time.

CURWOOD: Some of the costs include lives lost to the burning of fossil fuels, as some 8 million people around the globe and more than 300,000 in the US die each year from fossil fuel pollution, most from disadvantaged groups.

[MUSIC: Brian Rolland’s “Blues for doc Watson” on Long Night’s Moon, On The Full Moon Productions]

Treating people as more or less disposable inputs for the economic system helped to create the climate crisis, observes activist and lawyer Colette Pichon Battle.

BATTLE: That we could commodify this earth that we can commodify, the river, the tree, the water and the land. This is all rooted in a philosophy of extraction, and exploitation. This is the, this is the underbelly of our great society.

Colette Pichon Battle is an activist and lawyer who founded the climate justice and human rights center The Gulf Coast Center for Law & Policy. (Photo: Courtesy of Colette Pichon Battle)

CURWOOD: The flaw in this thinking she says is the belief that economies can infinitely expand, even though we live on a finite planet with limited resources. And seeking efficiencies by cutting costs and resiliency can have inhumane results, like the millions left frozen in the dark without water during the Texas power grid disaster in February of 2021. The state failed to consider climate related risks linked to the shifting polar vortex.

BATTLE: If you understand what's accelerating this human accelerated climate impact, you get to our economy. You get to capitalism. You get to extractive and exploitative practices that are rooted in a very dark past.

CURWOOD: So, looking forward to what could solve the climate crisis some say it comes down to who has power.

WILKINSON: I think in so many ways, money and power are really the crux of the of the issue, right?

CURWOOD: That’s Katharine Wilkinson, co-founder of the All We Can Save project and editor of the breakthrough book on climate solutions, Drawdown.

WILKINSON: Money and power is so much of what has kept us stuck in the status quo. It's so much what has caused denial delay, blockading by standing.

CURWOOD: According to Katharine Wilkinson, money determines who has the power to either maintain the status quo or transform the system, so to make the changes needed to save ourselves from climate catastrophe we have to think beyond dollars and cents, beyond national indicators like GDP.

Katharine Wilkinson is co-founder of the All We Can Save project and editor of the breakthrough book on climate solutions, Drawdown. (Photo: Buck Butler / Sewanee)

WILKINSON: We've somehow somehow seem to have landed on GDP is like the one big needle that we're all hearing about, you know, you tune into the news. And that's the key performance indicator that you're going to hear about, about how we're doing as a society. And, of course, sort of when we think about things that were laid bare by the pandemic, while it was you know, the gap between how the markets seemed to think we were doing last year and how average people were doing last year, we're wildly divergent. And if that sort of doesn't reveal some insanity to us, I don't know. I don't know what will.

CURWOOD: Katharine's done a lot of thinking about how to build a green economy, and to her a lot of it requires reframing the issue.

WILKINSON: I think a lot of times, our mind goes to oh, so that means, you know, installing wind and solar power. And that means retrofitting, building and building alternative transit. And I think all of that is true. But I think it also means recognizing, where we already have a quote unquote, green economy, but we've never seen it as such. So, for example, most care jobs right, the care economy is largely a green economy. It's largely a low carbon set of industries. Interestingly, predominantly held by women, and women of color.

CURWOOD: She foresees a green economy that is built upon unity, and says we’re moving in the right direction:

WILKINSON: Even as wealth inequality widens, even as concentrations of money and power in some way as are growing larger and larger, in a smaller and smaller set of hands. We're seeing the collective right rise up in various ways, as the corrective, the collective as the corrective to that situation and the collective as the means to shift the deployment of money and power towards a just and livable future.

Related links:

- The Brookings Institution | “Why Are Fossil Fuels So Hard to Quit?“

- All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Count Basie’s “Swingin At Newport – Live (1957/Newport)” on Count Basie At Newport]

CURWOOD: Just ahead on the program- call her Mother Earth, Pachamama or Gaia we’ll look at how understanding our place on the planet can help us keep livable climate. Keep listening to Living on Earth

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Count Basie’s “Swingin At Newport – Live (1957/Newport)” on Count Basie At Newport]

A Living Earth Called “Gaia”

Earthrise is the image of planet Earth taken from the Apollo spacecraft during the first manned mission to the moon, led by NASA in 1968. This event has continuously sparked interest in the beauty of the earth, and the possibilities brought forth by science. (Photo: NASA, www.earthday.org, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood

[MUSIC: Keith Jarrett Trio “Poinciana – Live At Palais Des Congres, Paris / 1999” on Whisper Not, ECM Records GmbH]

CURWOOD: One of the most fascinating aspects of science is the way its knowledge base is always changing, and new discoveries can come almost, if not entirely, by accident. Indeed, so many discoveries like radioactivity and antibiotics came when researchers were looking for something else in their laboratories and then, fortunately, had the good sense to pay attention when they got unexpected results. And some of that good sense comes from the humility of knowing that there are so many amazing things that accepted science still doesn’t understand. Consider, for example, that few of us would dispute the existence of love, though hopefully all of us have experienced it. But science cannot explain precisely what love is or even the exact process that creates, shares and enjoys love. Some day we may be able to explain in more scientific terms what is now the mystery of love, as unromantic that might sound, much as after millennia of observing birds fly, humans finally figured out the physics of how the birds do it so we could make wings to carry ourselves. When it comes to Earth’s climate there are still huge gaps in our knowledge of how the Earth stays neither too hot nor too cold to support life. The big unanswered questions are why and exactly how. We do understand which molecules reflect the sun’s heat and which ones can trap it. But modern humans have never lived through a major shift in the climate, so we can only speculate what might happen if the Goldilocks range of temperatures we need to survive are ever knocked out of whack. Right now, we are guessing that a more than a 2-degree centigrade rise in average global surface temperatures over preindustrial levels will literally start toasting civilization, and the climate disruption we already can see and feel comes from little more than a one-degree rise. Our guesses come from models run on supercomputers, but among their weaknesses they are poor at modeling clouds, and water vapor is our most prevalent greenhouse gas. But we humans do have the power to observe, and thanks to the observations of a genius named James Lovelock there is a hypothesis that could unlock a whole systems approach to protecting the amazing life forms that have arisen on Earth. Thanks to the suggestion of a friend, James Lovelock called it the Gaia Hypotheses, after the Greek Goddess who symbolizes Earth. Simply put, the Gaia hypothesis says the whole Earth system acts like it is alive and uses mechanisms that living creatures use to stay alive by constantly regulating temperature, chemical and physical inputs and outputs, and adapting through evolution. James Lovelock ,who turned 101 in 2021 came up with his accidental discovery when NASA asked him back in the 1960s to see if his inventions could detect life on the other planets by looking at their atmospheres.

[MUSIC: The Crusaders “So Far Away (1974 The Roxy)” on Scratch, The Verve Music Group]

CURWOOD: Venus, our nearest neighbor at 25 million miles closer to the Sun than Earth, is literally a hot mess with steady surface temperatures of nearly 900 degrees Fahrenheit, and an atmosphere of mostly carbon dioxide laced with bits of sulfur droplets. Not hospitable for life forms we know. Mars, 100 million miles further from the Sun than Earth is a bit less hostile to life with days of searing heat and nights of deep cold like our moon, but also with an atmosphere that is overwhelmingly made up of carbon dioxide with just tiny traces of oxygen. His genius kicked in when he realized the bigger question was not if there was life on those other planets, but why there was life on here on Earth. All three planets have histories of strong volcanos that spew out huge amounts of carbon dioxide. Left on its own the CO2 -belching volcanos on Earth would have led to a hothouse or desert over time. But something has kept carbon dioxide levels in a sweet spot, just four hundredths of a percent of the Earth’s atmosphere, enough to keep it warm but not too warm for life while the oxygen needed for animals is in great abundance. And that something is life itself. About a billion years after the Earth was formed, air, rocks and microbes likely came together and photosynthesis evolved. Photosynthesis is how plants, algae and other organisms convert sunlight into chemical energy and break down CO2 into its elements, carbon and oxygen. So, over millions of years plants and algae sequestered in their cells all that carbon from volcanos, and when buried in the ground or under the sea some of it eventually became coal and oil. Four times in Earth’s geologic history giant eruptions of volcanoes belched out so much CO2 they set off mass extinctions. There was also the mass extinction linked to an asteroid strike that likely shut down a lot of photosynthesis and allowed CO2 to rise. In every case Earth had to start sequestering carbon again as life evolved to adapt to new conditions. So, when we drill and dig up fossil fuels today, we are upsetting a balance the Earth works hard to keep. But if we keep those fossil fuels in the ground, we help support the living planet and all the life that we know about in the universe.

James Lovelock, shown here in 2005, is an English independent scientist who first proposed the Gaia hypothesis. (Photo: Bruno Comby, The Association of Environmentalists For Nuclear Energy, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 1.0)

[MUSIC: Xavier Rudd “Follow The Sun” on Spirit Bird, Salt.X Records Ltd]

CURWOOD: Many scientists have helped advance the Gaia hypothesis over time which now includes seeing the whole planet including life, atmosphere, water, and rocks as a single complex organism. Back in 1970’s the late UMass Amherst Professor Lynn Margulis co-published journal articles about the Gaia with James Lovelock. Her insights about symbiotic evolution rather than brutal competition suggested some mechanisms for Gaia’s self-regulation. One of the most public voices now on the Gaia hypothesis is a former student of James Lovelock, Stephan Harding. He is now a Deep Ecology Research Fellow at Schumacher College in England. In sum, he says, every living plant and animal on Earth interacts with the non-living rocks, atmosphere and water to make the planet an independent living organism.

HARDING: The scientific idea is that when they start interacting with each other, these four components, something extraordinary emerges out of those interactions, which you couldn't have known in advance. It's called an emergent property. It says the science is the ability of the whole of all four of them working together, all of them, life, atmosphere, rocks and water working together to keep the surface conditions on the planet suitable, or within the limits that life can tolerate. You see, life has a very important role here. Life is intimately involved in regulating the temperature, the acidity of the planet, the distribution of key elements. And so, the idea suggests that the earth is one great living organism.

Stephan Harding is an ecologist author, and Head of Holistic Science at Schumacher College. (Photo: Courtesy of Stephan Harding)

CURWOOD: One living organism. And as thinking about Gaia has evolved more credence is given to the notion that not just biologically active beings but also the so-called inanimate things like rocks and water can also support life. Observations reveal countless examples of the ways in which life in its many forms regulate the planet. Again, Stephan Harding.

HARDING: Well, basically, we now know that many kinds of organisms, including marine algae, and forests, like rain forest, they emit chemicals that seed clouds. And those clouds are dense and white and they cool the earth. And this is happening over the rain forests, and over parts of the ocean. So just think of that living beings are actually helping to cool the surface of the planet. I mean that's amazing . There’s more, there’s also we're pretty sure we know how Gaia has regulated her temperature, over geological time, despite volcanoes continually emitting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, which of course, as we know, is a greenhouse gas. And simultaneously, the sun getting brighter and brighter and brighter throughout geological time. So that now it's about 30% brighter than it was when life began maybe 4,000 million years ago or so. So, these two combined, you know, the increasing co2 in the atmosphere, and the increasing brightness of the sun is a recipe for an absolute disaster for life. eventually the planet will get so hot. The surface gets so hot, all the water would evaporate, boil off, like in a kettle. It's called a runaway greenhouse. That's what happened on Venus. But it didn't happen on Earth, because of life because of life interact, holding the water down, capturing the hydrogen as it was trying to flee.

CURWOOD: Many of the very chemicals we take for granted for life on earth are themselves a result of life on earth, including the oxygen from photosynthesizing, notes Martin Ogle a scientist and educator with Entrepreneurial Earth.

OGLE: If it weren't for life, that some huge number of the minerals on Earth would not exist. And so, if you just think of oxides, for instance, as many of the minerals of earth that they wouldn't exist, if it were not for life.

Martin Ogle is the founder of Entrepreneurial Earth and formerly served as Chief Naturalist for the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority for 27 years. (Photo: Courtesy of Entrepreneurial Earth)

CURWOOD: And by the way, a most valuable oxide is aluminum oxide in the form of the gem ruby.

Gaia as a living system is complex, and not fully understood. But just as we can observe and enjoy love without understanding its exact scientific mechanisms and we watched birds for millennia before we figured out the mechanics of flight, our observations can tell us a lot about Gaia. In fact, long before modern science emerged, traditional and aboriginal societies already saw the Earth as alive. Joe Bruchac is a Native American storyteller and tells the story of the Shinnecock tribe from Long Island.

BRUCHAC: It is said that in the 17th century, a group of missionaries visited there, and they gathered together a group of Native people. And assuming these people knew nothing about God or creation but had very unsophisticated ideas. They said, We wish to teach you about God, but do you have any idea of God or the creation? And then people said, oh, yes, we do. And let us show you, they drew a circle on the ground, and the earth, then they drew a very small circle in the center of that. And they said, this is the eye of creation. And we human beings are that small dot, the middle, surrounded by all the creation, by the great mystery, we are always in the eye of the creation, we're always seen by the great mystery. And the missionaries didn't quite know what to say in response to that.

CURWOOD: Today some people dismiss the Gaia hypothesis and the role of rocks and water in life as a pseudo intellectual exercise to put a more acceptable face on animism beliefs of aboriginal societies. But even a child in modern America can feel and express a deep connection to the earth in ways many of us lose or feel awkward talking about as adults. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb recently read Marc Majewski’s book for children, Does Earth Feel with some children in her life. The book poses 14 simple but profound questions for anyone to consider, including does the Earth feel?

Joe Bruchac is Nulhegan Abenaki elder, a storyteller and author of more than 120 books for children and adults. (Photo: Courtesy of Joe Bruchac)

ALL KIDS: Yes!

BASCOMB: Does Earth feel curious?

VERONICA: Yeah, it's curious because there's lots of fluttering animals like butterflies.

BASCOMB: Yeah. And then the question here is, does the earth feel hurt?

ALL KIDS: Yes. Yes.

BASCOMB: What? Why?

VERONICA: People aren't being as nice to it.

BASCOMB: What do they do that's not nice?

VERONICA: They chop down trees and shoot animals for fun. Because people put oil in the water.

BASCOMB: How do you think that hurts the earth?

SAGE: Because it hurts animals in the earth.

BASCOMB: Do you think when the animals are hurt the whole earth feels hurt?

SAGE: Yes!

CURWOOD: Stephan Harding says we are all born with an intrinsic understanding of Gaia.

HARDING: So it's, it's just our natural humanity to feel the earth is alive. And as a mother built into us, you could say, Oh, that's good. That's natural selection. those groups that felt the earth as a mother and treated her well survived. And those that didn't, and treated her like, like we treat her didn't survive. Quite right. Natural Selection. In a way, well I don’t know you can imagine a scenario like that. Modernity is headed for an extinction because of the way we relate. You don't relate to Gaia with our aboriginality we relate to her through our greed. You know, and our desire for more stuff and more money and more prestige and Competitive urges are just over exaggerated. So that council like that will be will go extinct.

CURWOOD: If modern humans don’t change our ways to find harmony with the earth Gaia will do it for us.

HARDING: That's a classic Gaian feedback. we've, we've pushed nature back, we’ve destroyed her to such an extent that there have to be very powerful feedbacks to control this species, the species of modernity. I won't say humans, because humans are wonderful, it’s modernity that's the problem. I've come to that conclusion, modernity, this modern way of life. It's a big problem. And it's evoking these feedbacks from Gaia. The coronavirus is just the start. I mean, if we don't do anything about greenhouse gases and the destruction of biodiversity, which help us control greenhouse gases, amongst other things, you know, we haven't got we haven't got much hope really? I mean, really? Not in the long term. That's the science.

CURWOOD: Perhaps the most powerful observations of Gaia come from people who have seen the Earth from outer space, including retired NASA astronaut Ron Garan, who flew in the shuttle and got to take a spacewalk.

Ron Garan is a retired NASA astronaut who spent 177 days in space, with 27 hours spent on EVAs, or extravehicular activities. (Photo: Robert Markowitz, NASA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

GARAN: As the payload bay doors opened, blue light was starting to seep in through the opening. And these massive payload bay doors, that was Earth shine, you know, reflected light from the Earth's surface. And as the payload base doors continue to open, eventually the horizon came into view. And when the horizon came into view, I was immediately thrust out of this disappoint of just being in an aircraft looking at the planet in high altitude to seeing the planet hanging in the blackness of space. A planet that all of the primates where no longer on. And so there was this feeling of detachment like I was physically detached from the earth, and that that feeling of detachment, I think, was immediately followed by something I can't really fully explain to this day, but that detachment, I think, led to this feeling of a deep interconnection with everyone and everything on the planet. It was as if for the first time in my life, I stepped outside the frame of the masterpiece, you know, we're looking at this beautiful, breathtaking, planet turning blue, you know, 240 miles below us was, was looking at it at a masterpiece. So, looking at this, this work of art, this, this beautiful thing, hanging in the blackness of space from the outside in. And I had obviously never seen the earth from that vantage point. And I thought about that, you know, when we when we look at, you know, go to the rim of the Grand Canyon, look at the Grand Canyon, when we sit on a beach at sunset and look at a beautiful sunset, gravity is pushing us into that scene, we're inside the frame of the masterpiece, we're part of that, of that painting, if you will. But for the first time in my life, I was seeing this exquisite beauty from the outside and, and somehow that outsider perspective, what I call the orbital perspective compelled me to feel deeply interconnected with everybody and everything on the planet.

CURWOOD: Ron Garan says the name Gaia is fine but he balks at the word hypothesis.

GARAN: I don't think it's a hypothesis. I think it's obvious I am seeing the planet from the vantage, that vantage point of space makes it obvious that we're looking at a living breathing organism, a multi celled organism, an organism that has different, you know, aspects of it, that based on the various, you know, multi varied species of life that exists upon the surface and below the surface of earth, and in the atmosphere of earth. And all of those different species, different individual animals, and plants are all part of an implicit wholeness, that is the planet itself. It's all not only interconnected, it's deeply, deeply interdependent.

The Blue Marble, a photograph of Earth taken by the crew of Apollo 17 in 1972. (Photo: Apollo 17 Crew, NASA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: One doesn’t have to go to outer space to feel Gaia. It can as simple as taking a moment outdoors to be aware of the beauty around you and feel yourself drawn into the presence of the Earth. And by the way, some skeptics say Gaia doesn’t qualify as a living being because things that are alive reproduce. Well, the simplest way organisms reproduce is by division. And some already envision a colony of humans and other Earth life forms on Mars. Indeed Perseverance, the most recent NASA expedition to Mars ,has an experimental machine called Moxie that mimics photosynthesis to produce oxygen. So, the gestation may be taking billions of years, but Gaia is in fact taking the steps to reproduce herself, which would truly make her Mother Earth.

Related links:

- Watch James Lovelock explain the Gaia hypothesis for Naked Science in 2007

- More on Stephan Harding

- More on Martin Ogle

- More on Joseph Bruchac

- More on Ron Garan

- More on Lynn Margulis

[MUSIC: Richard Strauss’s “Also sprach Zarathustra, Op.30, TrV 176: Prelude (Sonnenaufgang)” on Strauss, R.: Also sprach Zarathustra; Till Eulenspiegel; Don Juan; Salamone’s Dance Of The Seven Veils, Performed by Berliner Philharmonic]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Brian Rolland’s “Ask Me Again” on Dreams of Brazil, On The Full Moon Productions]

Ecological Conversion and Solidarity

“This is who you are”: In the Lakota language of Tiokasin Ghosthorse’s people, the word for water is “mni” and also conveys the idea of “the living relationship between you and I and all things.” (Photo: Linus Nylund, Unsplash)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: The Gaia hypothesis is a fairly recent take on cosmology that science is coming to respect more and more, but many ancient societies and religious traditions have long shaped our values based on being a part of, and not apart from the lives we share on this planet.

GHOSTHORSE: My name is Tiokasin Ghosthorse, and I am from the Cheyenne River Lakota reservation in South Dakota.

When I was four, my father had passed away. And I had spent the days in the summer along a small creek. And it was very warm, the sun was coming down, it was about noon, and I was watching the water and the crows and woodpeckers play, in their reflections. And I was sitting there, and I probably was thinking about my father, I don't remember but I felt a little sad. I heard some crunching of rocks on the ground, I looked behind me and at a distance around the bend of a creek came an old man. And this old man I've never seen before, but he had raggedy leggings on, and moccasins, and they were leather.

Tiokasin Ghosthorse is a member of the Cheyenne River Lakota Nation of South Dakota (Photo: Courtesy of Tiokasin Ghosthorse)

And he stood there, and I wasn't afraid of him for some reason. And he reached down, and he grabbed some dirt, some Earth, and he threw it out over the water, and it sprinkled, and you know how stones and pebbles hit the Earth -- there's small circles everywhere. And he said, this is who you are. And I was amazed and in that time construct of a young person four years old, you were looking at all the the circles and then you looked up, I looked up and I didn't see him, and he was not there.

CURWOOD: That mystifying experience stuck with Tiokasin. Later, he came to understand better what it meant.

GHOSTHORSE: So in life, I wanted to know what that that magic to me was, and it was basically water. And in the Lakota definition, "Mni", is the “m” means something like that which is related between you and I and all things. And “ni” is living, or life; and the “i” is voicing. So voicing the living relationship between you and I, and all things is what we call water. And water has consciousness.

CURWOOD: In the English language, we don’t quite have the words to convey what he is saying. But essentially, to the Lakota, water is more than the physical substance we splash on our faces in the morning, or use to slake our thirst. It is a way to define how we as individual people are connected to all of life.

GHOSTHORSE: You heard it out of Standing Rock: they were saying Water is life. "Mni wiconi”: water is life.

Joe Bruchac is Nulhegan Abenaki elder, a storyteller and author of more than 120 books for children and adults. (Photo: Courtesy of Joe Bruchac)

CURWOOD: But in many ways our current economic and political system lacks protection for our water and natural resources, which are essential for the health of the planet and humankind. And Native American beliefs like the Seven Generations Principle are counter to the destructive tendencies in our current systems that value transactions, short-term gains and efficiency over resiliency. Joe Bruchac is a writer and storyteller of the Nulhegan Abenaki Nation and sees this concept as a guideline for a better world.

BRUCHAC: We must think in terms of seven generations, what will happen seven generations from now, if I do this. And that goes way beyond ideas of investment, way beyond ideas of contemporary short-term politics, it becomes an investment in a future that is sustainable, that idea of seven generations is something central to my heart, and to the hearts of most people who live a traditional native way.

CURWOOD: People from other spiritual traditions are making similar connections. Rabbi Yonatan Neril, who directs the Interfaith Center for Sustainable Development in Jerusalem is one.

RABBI NERIL: The ecological crisis is not a crisis of the birds and the bees or the trees and the toads. It's a crisis of how we live as spiritual beings in a physical reality.

Rabbi Yonatan Neril founded and directs the Interfaith Center for Sustainable Development in Jerusalem. (Photo: Courtesy of Rabbi Yonatan Neril)

CURWOOD: He says spiritual leaders who see the ecological crisis through this lens find faith and hope in a variety of sacred texts.

RABBI NERIL: The teachings in, whether in the Bible or the Quran, or the Bhagavad Gita for Hindus, all sacred texts contain deep teachings about ecological sustainability. For one, the great spiritual masters of previous generations were living much closer to nature than the average human being is today.

CURWOOD: And today’s spiritual leaders are seeing that distance from nature, and the climate emergency, and calling their congregants to act. Pope Francis wrote Laudato Si’: the encyclical on climate change in 2015, which is a call for Catholics and non-Catholics alike to undergo an ecological conversion and care for our common home.

He writes, “Our planet is a mother for all of us. We must hand it on to our children, cared for and improved, because it’s a loan they make to us”. Pope Francis is famous for living simply in the Vatican and traveling in a small, unostentatious vehicle, the Kia Soul. Christiana Peppard is a professor of Theology at Fordham University and sees Laudato Si' in the canon of the followers of Saint Francis of Assisi, who dedicated his life to the poor, the animals and the environment.

Pope Francis spoke to the U.S. Congress in September 2015 about climate and other issues while thousands of climate activists rallied on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. (Photo: Stephen Melkisethian, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

PEPPARD: I think the Pope sees a lot of the dynamics of environmental degradation globally as driven by economic structures of profit, and a focus on economic development and growth that is not accountable to the limitations of what the planet can absorb, and it is not accountable to the burdens that are carried by people living in poverty.

CURWOOD: Like Pope Francis Father Albert Fritsch is a Jesuit priest who was trained in chemistry. The pope earned a master’s degree in chemistry and Father Albert a PhD in chemistry before either were ordained. Father Albert went on to co-found the Center for Science in the Public Interest in Washington and a related organization in Appalachia where he is now a parish priest and director of the website Earth Healing. There’s a very personal element to his environmental work. Asked if he had ever felt Jesus Christ speak directly to him, he told the story of visiting the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem which houses the rock where the body of Jesus was laid after he was taken down from the cross. There is a hole in the display case covering the rock:

Father Albert Fritsch is director of Earth Healing, a website dedicated to providing daily reflections on simple living and matters of faith. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

FRITSCH: And so I reached into the hole. And when I did, it was a voice came saying, “Look what they've done to my earth”. And it came as clearly as anything I've ever heard in my life. And so, when you asked me, What would Christ say? I said, I heard the voice of Christ. And it said it with tremendous sorrow, and difficulty because he thinks so much of his Earth: “look what they've done to my earth.” It changed my life. I never, I wasn't the same after that. But I feel that Christ was telling me that the Earth itself has been damaged, and that it hurts him very badly.

CURWOOD: From then on Father Albert devoted his work to caring for the environment. Islam also has much to say about ecology.

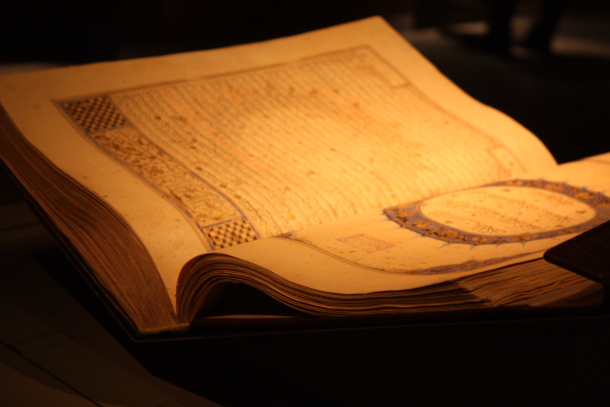

KHALID: Nearly almost every page as in seven, eight times out of ten you you turn the Quran randomly and you will get a sentence of a verse or a reference to the clouds, the sky, the birds, the bees, the trees, and creation and so on and so on.

CURWOOD: Professor Fazlun Khalid, is a theologian and Founder-Director of the Islamic Foundation for Ecology and Environmental Science.

KHALID: So, the Quran, I would say is an environmental manual. You see when the Quran talks about [Speaking Arabic], you see the Najm (star) and the shadows, the plants and the trees bow in adoration to Allah. And Allah says, then I created [Speaking Arabic] he says I created the world in balance.

The Qu’ran is filled with passages relating to the environment as the creation of God and highlights why humans must protect the earth. (Photo: Riyaad Minty, Flickr, CC BY-NC-2.0)

CURWOOD: In fact, this idea is at the very heart of some East Asian ways of thought.

Mary Evelyn Tucker is the co-founder and co-director of the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology.

TUCKER: Confucianism has a very rich cosmology, of continuity of being, of interdependence, and it's very specific: of cosmos, earth, and human. That's their Trinity, that’s their triad. We humans complete the triad of cosmos and earth. And we are co-creators with what they speak of as the transforming and nourishing powers of heaven and earth.

CURWOOD: Mary Evelyn Tucker explains that Lao Tzu is the progenitor of Daoism, with its values that include simplicity, humility and living in harmony.

A hanging scroll depicting Confucius, Lao-Tzu and a Buddhist Arhat. (Image: 丁云鹏 (Ding Yunpeng), Wikimedia Commons Public Domain)

TUCKER: Lao Tzu would say, we have to go with the flow, we've got to understand the power of water to carve out the Grand Canyon. We've got to understand that which is passive, hidden, dark, mysterious and yet generative of life and transformation. This is an extraordinary contribution to human thinking, nature's ways.

CURWOOD: So, from Lao Tzu and Daoism we have this idea of resonance with nature. Confucianism takes that a step further.

TUCKER: There’s a practical dimension to Confucianism. It says, that’s necessary but not sufficient, going with the flow. Because we also have to recognize human agency is critical. And if we don't align ourselves with these processes to create political systems, educational systems, and social systems for the common good, it will just be a personal transformation, that will feel good.

CURWOOD: What we choose to do, or fail to do, affects everyone around us. Rabbi Yonatan Neril speaks about self-interest and the climate.

RABBI NERIL: So there's a teaching from Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, who lived about 2000 years ago, in the north of Israel during Roman times. And he talks about somebody who goes onto a ship and starts drilling underneath his or her own seat, and the other people on the ship, say to the person, what are you doing? How could, how can you drill underneath your own seat? And the person says, Well, I'm doing whatever I want, because here's my ticket, and this is my seat, and I can do whatever I want. And the other people say to that person, well, no, you can't, because what you're doing impacts us. So, I think that this teaching has relevance for the climate crisis. Because each human being today, or most people, most of the 8 billion people alive today, are drilling underneath the collective ship of planet Earth. And similarly, on that ship, this person may not have been psychotic or crazy, this person may have just been trying to fish because they were hungry or get some fresh water because they were thirsty or put their feet on in the water because their feet were hot, the person may have been rational. And so too each of us is acting rationally, but but collectively, what we're doing is crazy, because we want the next generation to inherit a livable planet. But if we act with more spiritual awareness and engage in long term thinking, and care about other people and creatures, then we will actually be able to have a ship that is sustainable and seaworthy and can continue for many generations.

Mary Evelyn Tucker says, “Lao Tzu would say, we have to go with the flow, we’ve got to understand the power of water to carve out the Grand Canyon.” (Photo: Alan Carrillo, Unsplash)

CURWOOD: Stories from ancient traditions highlight this very idea: that we are not alone on the earth and our actions transcend through time. When Native American Joe Bruchac visited the jungles of the Mexican state of Chiapas, he spoke with Chon King Viejo an elder of the Lacandon Mayan people.

BRUCHAC: Chon King said, and I love this, though it's scary. He said, first of all, every time you cut a great tree in the forest, a star falls from the sky. So, before you cut a tree, you must ask the guardian of the tree, the guardian of the star, if what you're doing is correct. And he said, if we cut down all the trees of the forest, then the gods of diseases will come out of the forest and come among the people. He also said, if we cut all the trees, a great darkness will come upon the world. And in that darkness, you will hear the growl of the jaguar and you will be afraid. And so, if we do not maintain that balance, we are going to be experiencing that jaguars growl. That great darkness. So, to me, having traveled at some of the world, having met some of the people whose indigenous traditions I found so meaningful and similar to my own. I have to say that we all live on the same Earth, that our original teachings are very much the same. If we look to their relationship of us with our mother planet.

CURWOOD: It’s not easy to think that long-term, and we sometimes fall into the trap of thinking that we can engineer our way out of our problems and into the future. That’s only part of it. As we conclude, here are some voices, starting with Mary Evelyn Tucker.

Mary Evelyn Tucker co-founded and co-directs the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology alongside her husband, John Grim. (Photo: Courtesy of Mary Evelyn Tucker)

TUCKER: We've got a lot of the science and technology and economics and policy. But we don't necessarily have this deep, inner, spiritual sensibility that we can make it through this bottleneck of extinction, and climate emergency and so on. So, the human spirit needs care and activation on every level, I think.

RABBI NERIL: Over the past 12 years, I've been involved in interfaith environmental work. And I have the privilege of working with amazing people, priests, pastors, Imams, Swamis, monks, who care deeply about ecological sustainability and are approaching it from their different religious traditions. So, you know, it's a commonality, it's, and that's, you know, if we're on a, we're on this ship together. And and so the most important thing is that we learn to live here sustainably together.

CURWOOD: That was Rabbi Neril, and finally, Mamphele Ramphele is a South African physician, activist and widow of Steve Biko. She says our gifts of today are bright possibilities.

RAMPHELE: And so we now have an opportunity to reimagine a world where we see ourselves as part of nature. We are not saving nature; nature will save itself. We have to save ourselves from this existential crisis by changing fundamentally the way we live, how we relate to one another, and how we relate to the rest of life. And that's the opportunity we have.

Related links:

- Read the Encyclical Letter Laudato Si’ of the Holy Father Francis on Care of Our Common Home

- About Tiokasin Ghosthorse

- Learn More about writer and storyteller Joseph Bruchac

- Learn more about Mary Evelyn Tucker and the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology

- Watch an interview hosted by the Islamic Human Rights Commission with eco-theologian Fazlun Khalid on his book Signs on the Earth

- About Rabbi Yonatan Neril and the Interfaith Center for Sustainable Development

- Learn more about Father Albert Fritsch’s website, Earth Healing

[MUSIC: Keith Jarrett Trio “Poinciana – Live At Palais Des Congres, Paris / 1999” on Whisper Not, ECM Records GmbH]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Grace Callahan, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Paige Greenfield, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Natalie Seo, and Jolanda Omari. Jake Rego engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood, thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth