The Colorado River’s Dwindling Water Supply

Air Date: Week of May 14, 2021

The thick white “bathtub ring” at shrinking Lake Mead, which is impounded by Hoover Dam. (Photo: Ricardo Frantz on Unsplash)

The Colorado River that carved the Grand Canyon and now quenches the thirst of much of the American West is parched in a “megadrought.” Two key reservoirs are expected to drop to record low levels this year and trigger a formal water shortage declaration. Reporter Luke Runyon covers the Colorado River Basin and joins Host Steve Curwood from station KUNC in Greeley, Colorado.

Transcript

CURWOOD: The Colorado river that carved the Grand Canyon and now quenches the thirst of much of the American West is parched in a “megadrought,” with two key reservoirs expected to drop to record low levels this year. Lake Mead behind the Hoover Dam is the biggest human made reservoir in the US and it’s now just 43% full. Our second biggest reservoir, Lake Powell behind the Glen Canyon dam, is even worse off at just 35 percent capacity. With forecasts that hot and dry drought conditions could persist for years, the odds now favor the federal government declaring a formal water shortage in the Colorado River Basin later this year. Reporter Luke Runyon covers the Colorado River Basin and is on the line now from station KUNC in Greeley, Colorado. Welcome to Living on Earth Luke!

RUNYON: Hi, thanks for having me.

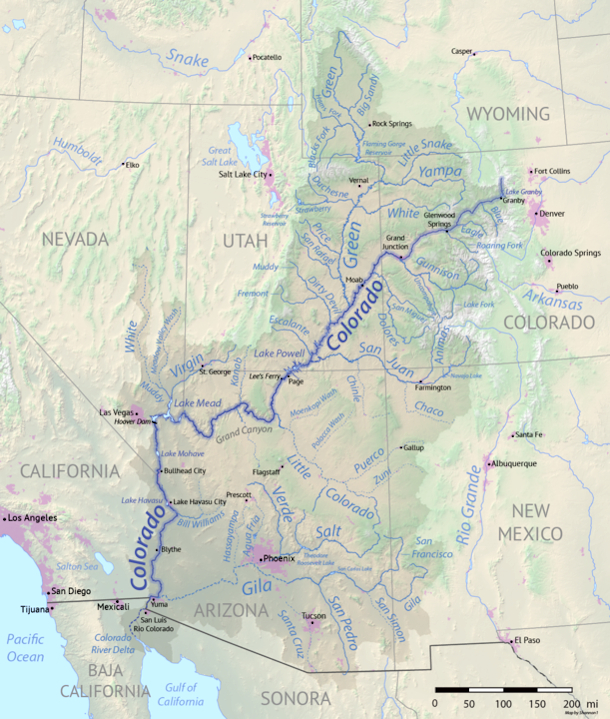

CURWOOD: So Luke Runyon, you cover the Colorado River Watershed as a beat, huh? What's the extent of the watershed?

RUNYON: So the Colorado River flows through seven US states. Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Wyoming make up the upper watershed. And California, Nevada and Arizona make up the lower watershed. It also crosses over the US-Mexico border and two Mexican states use water from the river as well. And it acts as a drinking water supply for some of the West's largest cities; when you think of Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Denver, they all pull water from the Colorado River. And it also acts as a really important agricultural irrigation water supply. You're looking at some of the most intensely farmed areas of the country: California's Imperial and Coachella Valleys use water from the Colorado River; the Yuma, Arizona area, which is kind of the "lettuce basket" of the country, that uses Colorado River water as well. So it's a really important water source for a large swath of the American Southwest.

Lake Powell is holding just 35% of its capacity. (Photo: Zetong Li on Unsplash)

CURWOOD: Wow, how big is the Colorado River flow when it's at its full-throated strength? Compare it to another major river for me, would you?

RUNYON: Well, it's actually, if you compare it to, like, the Mississippi River, it's a very small river. It, you know, it flows through some of the most arid reaches of the country. But we've tasked the river with a lot of different jobs. Because the area is so arid, the reliance on the Colorado River is huge. And there's just not enough water supply to go around. And so it's an intensely managed system in order to try and stretch it as far as we can.

CURWOOD: Now just how low today are the Colorado River water levels? We're speaking in May of 2021.

RUNYON: The Colorado River, you can kind of judge its health based on its two largest reservoirs. And this is Lakes Mead, and Lake Powell, which are in southern Utah for Lake Powell, and kind of the border between Nevada and Arizona, near Las Vegas, for Lake Mead. They are approaching record low levels. And that's because we've had essentially 20 years of above average temperatures in the basin, and below average flows on the whole over that 20 year period. And that's showing up in these reservoirs that are supposed to cushion between the really dry years. We're also seeing some changes in soil moisture, which is another thing, it's kind of like the hidden water bank. We always get so focused on surface water because we can see it, we can, you know, look at a river and know, oh, the river is high, or the river is low. But groundwater plays a huge role in the Colorado River Basin. And right now, soil moisture levels in parts of the Colorado River Basin are at the lowest that we've ever seen, and some much below the record. And you can kind of think of the ground as this giant sponge: when it's really dry, any new precipitation that falls, it's going to fill up that deficit that's left in the ground before it flows off into rivers. And so even a year where you have decent snowpack, you can see that snow not necessarily turn into a huge amount of water supply, because it's getting soaked up by that sponge in the ground.

CURWOOD: Now how much of the shortage in the Colorado River system is because of growing demand, that we have more and more people in places like Los Angeles and Phoenix and throughout the Southwest?

The Colorado River basin. Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Wyoming make up the upper watershed, while California, Nevada, and Arizona make up the lower watershed and two Mexican states use water from the river as well. (Photo: Shannon1, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

RUNYON: Demand definitely plays a role. But I think the biggest concern really is on the declining supply. In a lot of big cities in the West, demands have been flat, or in some cases have actually declined. And there are many different case studies of cities that have been able to grow while having their water demands either stay static or actually decline. The problem really is when you have the same amount of demand that you've had for a long time, but then the supply is shrinking. Those demands have to shrink along with that supply. And that's really the hard part. And those are the hard discussions that are going on in the basin right now, is, whose water supply should be curtailed in order for us to match the declining supply that we're seeing? And that's a really hard discussion to have, because we've built up massive cities and we've built up agriculture. We have all these expectations of what the river is is supposed to deliver to us and it just doesn't want to deliver that anymore, because of climate change and warming temperatures.

CURWOOD: So what are water officials on both, well, the regional as well as the national, federal level, saying they're going to do about this shortage?

RUNYON: It's not like there's one agency, or one overriding commission that makes all of the decisions on the Colorado River. It's managed by all of the people who, who depend on it. All of the various agencies and states, the federal government plays a role. And so it has to be collaborative by nature, because all of these various entities have to come to the table and decide who gets what amount of water. And they come to these agreements. And right now, all of these various entities are coming to the table, deciding how to implement old agreements and how to come up with new ones. And really, the driving question is, who has to use less water? The current agreement that the watershed is under is called the Drought Contingency Plan. It was passed in 2019. And really, it's kind of a band-aid to some of the past agreements that haven't been enough to halt the decline in some of these reservoirs. The Drought Contingency Plan lays out this series of cutbacks that Arizona, Nevada, Mexico and California have to take as Lake Mead declines. As the level of the reservoir gets lower, those states and the country of Mexico have said, we will take less water from the Colorado River.

Most of the water people take from the Colorado River quenches the thirst of crops like lettuce in Yuma, Arizona. (Photo: Tina Sibley, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, to what extent would the federal government be in a position to come in and, say, declare an official water shortage situation? I gather if the Interior Department were to declare that there is an official water shortage in the Colorado River Basin, it would trigger, I would think, some reductions, even some mandatory cuts. What's the status of that at this point?

RUNYON: We're looking at a very high likelihood of an official water shortage being declared in the Colorado River Basin later this year. That declaration is tied to the level of Lake Mead. And so when Lake Mead dips below a certain threshold, within an agreement, it says that the Interior Secretary will be able to declare an official water shortage. And it's a bold statement, saying, we don't have enough water to meet everyone's needs.

CURWOOD: So Luke, to what extent can water conservation practices help alleviate the shortage, bring things back from the break?

RUNYON: It depends on the type of water conservation practice that you're talking about. If you're talking about like a large, systemic conservation initiative, like installing a new water recycling plant in a large city, that can play a huge role in, you know, ensuring that that city has enough water to meet the really dry times ahead. You know, a lot of cities in the Colorado River Basin have put some effort toward getting people to remove their lawns because outdoor residential water use is some of the largest water usage in a large metropolitan area. So I think the individual decisions that people make play a really big role. But the Colorado River Basin is such a large, complex system, it really takes states, large governments, federal agencies coming together to manage this crisis. Because really, these issues are so much larger than just the individual decision.

CURWOOD: As I understand it, what, 70, 80% of the water in the Southwest goes to agriculture, to growing things, even some things that are not very water efficient, like rice, or hay. What are ways that agriculture could conserve water to help alleviate this, this shortage?

RUNYON: You can talk to a lot of farmers who say, yes, we need to figure out how to use water more efficiently. You know, we need to be looking at different types of infrastructure, different methods to irrigate, maybe even different crops to grow in order to be more water efficient. You're also starting to see some of the states talk about what they refer to as demand management. So these are programs that would essentially pay farmers not to irrigate, and send that water downstream for another use or put it into a reservoir for later storage.

Reporter Luke Runyon covers the Colorado River basin for KUNC and 20+ NPR stations in the southwest. (Photo: Courtesy of Luke Runyon)

CURWOOD: You know, given the effect that climate disruption is having on drought and, and water usage, what's the long term outlook for water supplies in the West and Southwest?

RUNYON: Yeah, and I wouldn't want somebody to hear this conversation and think that, you know, we're quickly approaching Mad Max-style water wars in the Southwest. But I do think that there is a certain level of alarm that you're hearing from those who pay really close attention to the Colorado River. You're starting to see a lot more scientists, you know, water managers, saying that this is a huge issue and it needs a lot of attention and it needs a lot of investment in order to make sure that, that we don't approach the level where we're having people fighting over water in the Colorado River Basin.

CURWOOD: Luke Runyon is a reporter with KUNC in Greeley, Colorado, who covers the Colorado River Basin. Luke, thanks so much for taking this time with me today.

RUNYON: Thanks, Steve.

Links

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation predicts at least 2 more dry years ahead for the Colorado River Basin

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth