May 14, 2021

Air Date: May 14, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Youth Activists Win Stronger Climate Action in Germany

View the page for this story

After a trial brought forth by youth climate activists, Germany's highest court recently ruled that present government commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are insufficient to protect future needs. At the same time, the German Green Party is leading in the polls. Nils Meyer-Ohlendorf is a governance expert for the Ecologic Institute based in Berlin and joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the support for strong climate action in Germany. (08:13)

French Climate Bill Disappoints Activists

View the page for this story

In France, the government is moving ahead with a climate bill shaped by citizen proposals. But those citizens say the government has weakened their proposals and the public has taken to the streets to protest. Lola Vallejo, the climate director for the think tank IDDRI, joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about the climate legislation and the social response. (06:32)

Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future

/ Aynsley O'NeillView the page for this story

Humans have altered the environment in innumerable ways. We’ve reversed rivers, introduced invasive species, and disrupted the climate. In the new book Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future, Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Elizabeth Kolbert explores cutting edge and controversial technologies aimed at solving some of these problems. She joins Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill. (14:14)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Host Steve Curwood and Environmental Health News editor Peter Dykstra go beyond the headlines to discuss the record-breaking rates of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest and the battle over the future of offshore wind development in Maine. They also revisit the anniversary of solar cell manufacturing company Solyndra’s public collapse in 2011. (04:34)

Note on Emerging Science: Biochar and Irrigation

/ Casey TroostView the page for this story

Intense drought in the Western United States has led to record-breaking wildfires in recent years, but new research shows that fire may indirectly help to conserve water in drought-prone areas. Living on Earth's Casey Troost has this note on emerging science about the benefits of biochar. (02:21)

The Colorado River’s Dwindling Water Supply

View the page for this story

The Colorado River that carved the Grand Canyon and now quenches the thirst of much of the American West is parched in a “megadrought.” Two key reservoirs are expected to drop to record low levels this year and trigger a formal water shortage declaration. Reporter Luke Runyon covers the Colorado River Basin and joins Host Steve Curwood from station KUNC in Greeley, Colorado. (11:27)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

210514 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Elizabeth Kolbert, Nils Meyer-Ohlendorf, Luke Runyon, Lola Vallejo

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Casey Troost

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Germany’s high court rules in favor of young people who want stricter climate measures as the Green Party now leads in the polls.

OHLENDORF: I think there is a sentiment in a pretty large part of the population that there should be a change, there should be something new. We still have 5 months to go to the election but if that sentiment of we want change is lasting, I think the Greens have a fair chance to win the election which would be truly historic.

CURWOOD: Also, much of the Colorado River basin is experiencing a megadrought, forcing tough decisions about who gets water.

RUNYON: If you compare it to the Mississippi River, it’s a very small river but because the area is so arid the reliance on the Colorado River is huge and there’s just not enough water supply to go around.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Youth Activists Win Stronger Climate Action in Germany

Thousands rally across Cologne Germany during a Fridays for Future Climate strike. (Photo: Marco Verch, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Young people have the human right to effective action to combat climate disruption, says the highest court in Germany. The German Constitutional Court recently ruled present government commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 55% below 1990 levels within this decade are insufficient to protect the future. The high court’s order for stronger climate action appears to reflect broad German public opinion, and polling shows the Green party may well lead the German government after the September elections. Chancellor Angela Merkel is retiring after sixteen years of shaping some of the world’s strongest climate policies. Trained as a chemist, her understanding of science has helped her lead a series of German government coalitions committed to climate action. But deepening awareness of the climate emergency is raising stakes on climate even further in German politics. Nils Meyer-Ohlendorf is a governance expert for the Ecologic Institute based in Berlin, and he joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

OHLENDORF: Good to talk to you.

CURWOOD: So recently Germany's high court rule that a law passed in 2019 there to protect the climate is insufficient to protect future generations. What impact does that have now on the political mix there in Germany?

In Munich, Fridays for Future organizes a human chain and a petition delivery to Siemens Energy to stop coal mining in Australia. (Photo: Zack Helwa, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

OHLENDORF: It has a huge impact on Germany's climate policies. And you can see that the German climate law that you just mentioned, will be revised. And the Ministry of Environment proposed to scale up Germany's reduction target from currently 55% by 2030, compared to 1990 to 65. There will also be a target for climate neutrality, not by 2050, but by 2045. So that is already a drastic change. And on top of that, the state of Bavaria, which is one of the largest German bundeslander or states, is also one of the most conservative, if not the most conservative states, has voted to reach climate neutrality by 2014 rather than 2015. And that was really the aftermath of that court decision. So the court decision in fact, has a big impact. To what extent it has an impact on the politics and the election campaign, we will see. But I mean, it's just like the official blessing to much more climate policies. And it's just the official seal, if you like, for what the greens have been advocating, and environmental NGOs have been advocating for a very long time. And I think it's important to understand that the Constitutional Court in Germany is not only the highest court in the country, it's also one of the most respected institutions in the country. So it really has a lot of authority, not only in terms of law, but also in terms of this is one of the most trusted institutions in Germany and if they have the statement, if they make this verdict, it matters to many people.

CURWOOD: There's been litigation here in the United States, in the federal courts to try to say that federal policy isn't protecting the future of young people well enough, that has not succeeded in the courts. What is it about Germany that in fact, young people could sue and get a ruling saying that yeah, present climate policy isn't protecting our futures and the government needs to do more?

OHLENDORF: Well, it's the procedural structure of that court, and the German law, every single citizen is entitled to go to the Constitutional Court, claiming that he or she has been violated in his or her constitutional rights. The main argument of the court was the human rights in basic freedoms of future generations. The court ruled that if we use up a very large chunk of remaining emissions before 2030, then there will be very little left for future generations, meaning their freedoms to do all kinds of different things would be infringed. And that is why the court ruled that there should be a target after 2030. That is important to understand the court did not rule that the current 2030 target would be unconstitutional. The court said it is unconstitutional to leave so little emissions remaining after 2030 for future generations. So that was the main argument of the court.

Annalena Baerbock is a German politician serving as a co-leader of Alliance 90/The Greens and candidate for the chancellor for Germany in the 2021 elections. (Photo: LDK Dortmund, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: The Christian Democratic Party has governed Germany for much of the last 16 years under the leadership of Angela Merkel. But now as she has said that she's stepping away the Green Party is leading in the polls, what's going on?

OHLENDORF: The greens and the Christian Democrats, they were actually neck to neck more or less last year, before COVID hit the country. And then COVID hit the country. And that was, I think the main reason why the Christian Democrats were increasing their shares from the post drastically. So they went from about 27 - 28% at the time, to 40%. And that was because they were trusted as the solid party in government, who has a long history of managing the country. And now this image of being the natural party of government that is changing because Germany is not handling the COVID crisis as efficiently anymore as it did during the first wave. And lots of people are frustrated how vaccination is being rolled out how testing has worked. I mean, it's it has been improving, but I mean, it has not been managed well at the beginning. And now we're looking at the lockdown in the country for almost six months now. So a lot of people are really frustrated, and they put the blame on the leading party, which are the Christian Democrats and that was the main reason why they're going down and the greens are going up.

CURWOOD: So there's been some intense squabbling now between the Social Democrats in the Christian Democrats recently to what extent do you think that is helping the Green Party?

OHLENDORF: I think what is helping the Green Party are various things. I mean, one is that this coalition, the coalition of the Christian Democrats, and the Social Democrats, appears to be worn out. They have been in power for most of last 16 years. And I think there is a sentiment in a pretty large part of population, there should be a change, there should be something new. And if you look at the candidates, I mean, the Christian Democrats that is Armin Laschet, who is from North Rhine Westphalia is a lawyer on the one hand you have Olaf Scholz, who's leading, who’s candidate for Chancellor who Social Democrat who is also a lawyer. And then on the other hand, you have Annalena Baerbock, who is 40 years old, who is not a lawyer, who is a fresh face, only still five months to go to the election. That's a long time. But if that sentiment of one change is lasting, I think the Greens have a fair chance to win the elections here, which would be truly historical.

Angela Merkel has been serving as the chancellor of Germany since 2015. She has been nicknamed as the “Climate Chancellor” for her work in keeping with Germany’s emission goals. (Photo: Arno Mikkor, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Niels before you go, the climate talks a UN climate talks, the Conference of the Parties is coming up in November in Scotland. How will the then September federal elections in Germany do you think influence your country's climate goals and ambitions during those negotiations?

OHLENDORF: That is hard to tell at this point, because we don't know the composition of the next government. But I think it's the most likely scenario that the Greens will be member of the next government. But even without them and I think that's really important to understand. It's the country as a whole that has embraced climate to a new level, I would say. So but what I find really interesting is that we are in the midst of a deep economic crisis. I mean, Germany has not hit as bad as other EU countries. But still, unemployment has gone up, public debt has increased drastically. So there is an impact that COVID had on our country and quite a bit actually. And yet, despite that, we see a very broad agreement on increasing our climate ambition. And I think that is really something to be noted that in the midst of an economic crisis, we decided to do more, because we believe it makes economic sense.

CURWOOD: Niels Meyer Ohlendorf is the head of international and European Governance for the Ecologic Institute in Berlin. Thank you so much for taking the time with us.

OHLENDORF: Thank you so much, Steve. pleasure talking to you.

Related links:

- DW | “'German Law is Partly Unconstitutional, Top Court Rules”

- The Guardian | “'Polls put German Green Party in Lead Five Months Before Election”

- Clean Energy Wire | “'Polls Reveal Citizen Support for Climate Action and Energy Transition”

French Climate Bill Disappoints Activists

CURWOOD: We turn now to Germany’s western neighbor, France where the “yellow vest” movement has been protesting social and economic inequalities since 2018. The protests began when a carbon tax caused an increase in fuel prices that disproportionately affected low-income citizens. In response to the protests the French President, Emanuel Macron, formed the Citizen’s Convention on Climate which randomly selected 150 French citizens and asked them to come up with proposals to reduce carbon emissions from France in a way that was more socially just. The convention spent 9 months at the task and came up with 149 proposals to dramatically curtail French emissions. But by the time the proposals made their way through the French legislature members of the commission say they their bold ideas were weakened and watered down, prompting some activists to take to the streets.

[SFX PROTESTS]

CURWOOD: Lola Vallejo, is the Climate director for IDDRI an independent think tank based in France, focused on sustainable development.

VALLEJO: I think part of the disappointment we're seeing now in French society at large, but more particularly from the citizens, is that they made some very consistent policy proposals. And they have just been disappointed by what the government and what the Congress has done with their proposals. Based on their proposals, the government has proposed a draft bill, that was actually already cherry picking among the measures that they proposed, it was either, you know, suggesting to delay their implementations or suggesting to narrow their enforcement. So already, citizens were concerned about the lack of teeth of the proposal. And then as it went through lecture through Parliament, then many felt like it wasn't really strengthened, but maybe even weakened further. And also, we've just heard that one of the symbolic measure of the work of the citizens was to suggest a referendum to amend the constitution to create a new crime against the environment called the ecocide, which would basically make it easier to sue against those that were responsible of crime against the environment. And Macron has just announced that it's actually pretty likely that there will not be a referendum. So either the law and the referendum not happening that means that the citizens are just pretty disappointed with what happened to their work.

CURWOOD: So what are some of the most important parts of the climate resilience bill that the government is putting forward? Could you give me some specifics, please.

VALLEJO: So one of the most implementing measures of the slow is that it bans domestic flights, when there is an alternative that takes you less than two and a half hours. In France, we're lucky to have a good rail network and if your rail journey takes less than two and a half hours, then you will not be able to take plane and you will have to take the train. So this is a very emblematic measure, because it's the first time in the world that there is any kind of ban to domestic flights. However, this is an example of a measure which has still disappointed activists because first, the proposal from the citizens was to have this ban for any trip, that would take under four hours, and not two and a half. And then there's also another loophole, which is if this flight is for connecting flight, then that means you can still maintain the line.

The French President Emmanuel Macron has been criticized for taking too little action to combat climate change. (Photo: Présidence de la République, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So we've seen in France, President Macron tried his fuel tax, which immediately set off the the yellow vest movement protests. Now we see protesting against the proposed climate legislation, because it's not strong enough. What's going on in France, how much of a crisis is the climate now for France do you think?

VALLEJO: I think it's good to take a step back maybe about what the gilet jean we're about, because I think what the protesters were criticizing was not so much the hike and the carbon price. But also maybe underneath that the overall system of how we address carbon, if you just put a price on carbon, that is the same for everyone it's not a progressive policy, because there are a lot of people who are locked into carbon intensive ways of living. And if you don't give them alternatives to switch to low carbon lifestyle, then this is just really bad for social justice. I don't think there is a discontinuity between the yellow vest and what we're seeing today, because there always has been a very strong support for strong environmental action in France, and even the gilet jaune were in agreement with that. But effectively, the French people do want strong environmental action. They just wanted to be fair. So progressive climate action policies are going to find a strong support, it's just that we haven't seen them at the scale that is needed.

CURWOOD: How important is this fight over having a constitutional amendment creating this class of crimes that will be known as ecocide?

VALLEJO: I mean, opinions differ. To be honest, it was more of a symbolic measure for the convention, it was also a way to ensure that environmental protection was given a higher status in our Constitution. I personally don't think it's, you know, it's going to make a big difference not to have the referendum and not to have this sentence in the constitution is not going to change that much on a daily basis. What is negative though, is more about how people view the political promise because there has been a promise made by the President of the Republic to citizens to have this referendum. And he said, I'm going to take your proposals without a filter, that was the expression he used. And I think that's just quite dangerous to have this experiment and to raise the hopes of these citizens and more broadly of any environmentally minded person that followed this process and then to show that there is actually some level of disregard of the work that the citizens have done and not to actually respect the promise that the President made. So I think that's, that's probably the more dangerous consequence of this lack of referendum is more on how much people value the things that are said by our politicians.

CURWOOD: Lola Vallejo, is the climate director for IDDRI in Paris, France. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today, Lola.

VALLEJO: Thank you very much. It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- DW | “'France’s Citizens Climate Assembly”

- Climate Home News | “'French Draft Law Criticized for Weakening Ambition of Citizen’s Assembly”

- Euro News | “'Protests Across France Over ‘Pseudo’ Climate Change Bill”

[MUSIC: Rouge, “Bravo, Pour le Clown!” on La Terre des Nos Desirs, by Louiguy/Contet, Rouge Music]

CURWOOD: Coming up – how one idea to slow climate disruption could turn the sky white. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ninine Garcia Quintet “Revoir Paris” on Nouvelle vie, Djaz Records]

Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future

Solar geo-engineering could cool the planet but could leave behind a white sky. (Photo: Wilbur Ince, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

In 2015, Elizabeth Kolbert won the Pulitzer Prize for her book The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History, which chronicles the human-made mass extinction crisis. Now she's out with a book that explores some cutting edge and controversial technologies that could address some of the world's most pressing environmental challenges. Her book, Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future features scientists and other leaders who argue that in order to save the planetary systems that humans have altered, we must alter it again. Elizabeth Kolbert spoke with Living on Earth's Aynsley O'Neill about some of these controversial new technologies including the gene-editing process, CRISPR.

O'NEILL: When it comes to human hubris, there is the as always, cynics saying, well, you're playing God here. And what I'm talking about is microbiology and genetic engineering and CRISPR, physically changing the genetic composition of an organism. How does this process work? And where does that come into play in your book?

The Cane Toad is a poisonous amphibian that is invasive in Australia. Scientists are working on genetically modifying the animals to break their toxicity genes. (Photo: Brian Gratwicke, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

KOLBERT: So CRISPR is a set of gene editing techniques that humans have borrowed from bacteria, interestingly enough. So what bacteria do is they can incorporate little bits of viral genetic material into their own genome. And then they use those as like mug shots, so that they can identify their enemies. They create these enzymes that can cut their enemy at very precise locations. And so now it's been discovered that you can program these enzymes basically, you can just program this system to cut DNA wherever you want to. And that's incredibly powerful. It really revolutionized gene editing. And that has opened up a lot of possibilities, including in the world of wildlife conservation. And one of the projects that I've visited in Australia, which was at a very, very bio secure one of the most secure facilities in the world in the city of Geelong, near Melbourne, they were gene editing an animal called a cane toad, which is an invasive, very destructive, invasive species. Cane toads are highly toxic. And so a lot of creatures eat them, you know, reptiles, snakes, lizards, birds, mammals, they're marsupials, now. And Australia, for for many reasons, mostly having to do with introduced species, is the mammalian extinction capital of the world. More of Australia's native mammals have gone extinct than anywhere else. And they're very, very interesting fauna, this unique marsupial fauna. So cane toads are considered a big, big threat, because you know, whatever eats them tends to drop dead. And certain animals have really, their populations have really plunged as soon as cane toads come into their territory. And so the idea behind this experiment was to see if you could sort of break the toxicity gene. There's one gene that creates an enzyme, which really makes their toxin much, much more potent. And so if you could basically disable that gene, which which they had done, the toads would be a lot less toxic.

O'NEILL: And there are those critics of CRISPR out there, what do they say? And how do you respond to that?

KOLBERT: You know, these animals were never leaving the lab, the ones that had been gene edited, but the question obviously arises, should they be allowed to leave the lab? And, you know, if they're aiding in a conservation project, would we want them you know, out there, you know, in that helping the world, helping a species, or maybe many species recover? These are really, really hard questions, and they do get into the playing God question. Now, one thing I will say is, you know, the guy who was in charge of this project that I visited, a scientist by the name of Mark Tizard, is very, very nice guy. He made the point to me, which I also thought was very compelling. Look, we're playing God all the time. You know, we are moving things around all the time. You know, your pets are not native species. You know, everything that you plant in your garden, much of it is probably not a native species. Every day in the ballast water of our supertankers, something like, you know, 10,000 species are being moved around. We're just doing it kind of willy nilly, we're not doing it purposefully. But we're moving whole genomes around and what gene editors do is they move, you know, a tiny sliver of DNA. So, you know, you can think about that we're playing God all the time. We're just ignoring that fact. So these are interesting things to think about. And that's really at the heart of the book, some of these questions, which are very, very difficult to answer, right. And I don't want to say there's a right answer here.

O'NEILL: You also describe something in the book known as the gene drive. Can you tell me about that, please.

Using “gene drive” technology, scientists have come up with mosquitos that could potentially deplete their own populations. (Photo: Eli Christman, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

KOLBERT: So gene drive is a really interesting phenomenon. And gene drive exists in nature. There are genes, many of them probably, that defy the ordinary rules of inheritance. So you get two sets of chromosomes, right? One from your mom, one for your dad. And then when you go to pass on your genes, you will give one of those variants to your own children. And your mate, you know, will give one too. But some genes manipulate the rules of inheritance. They're very sly. And they pass themselves on more than 50% of the time, often, much more than 50% of the time. So those had been identified in the natural world. Now, what CRISPR allows you to do which is one of the many reasons that it's really a revolutionary technology is it allows you to, it itself is the whole system, the whole gene editing system is in effect encoded in DNA. It's a biological system. And you can insert that system into an organism, and basically program it to reprogram its own genetics, and then can be passed on generation after generation. And so what gene drive allows you to do is if you want a certain genetic variant to spread, you can insert that. And gene drive mosquitoes already exists. They are mosquitoes, that would pass on a trait that's quite deleterious, that makes it very, very difficult for them to reproduce. And so, in theory, at least, these mosquitoes as the generations go on, are basically doing themselves in. And it is planned or hoped by some people, how's that, that these mosquitoes that already exist, as I say, will be released in a part of Africa, where malaria rates are very high, and where a lot of people are dying of malaria. And it raises a lot of, you know, once again, profound questions. But gene drive could also be used for all sorts of other purposes. So a group that I visited also in Australia, also to a very bio secure facility was working on a gene drive mouse. And the idea behind the gene drive mouse was that invasive rodents are extremely destructive, you know, humans brought rodents everywhere, brought rats, brought mice. And they have been responsible for hundreds and probably more extinctions on islands, especially birds, like ground nesting birds. And so the idea, the hope, is you could create a gene, drive rodent, rat, or mouse. So you start with a mouse, that would also do the same thing as these mosquitoes, carry some deleterious trait that would eventually drive the population to zero. And you could release them on an island, once again, the hope, the theory, could release them on an island where they would only do in the other rodents on this island, they wouldn't do in you know, every rodent in in the world. But you know, that raises a lot of, you know, once again, complicated questions.

O'NEILL: It does raise a lot of interesting questions. And near the end of the book, you delve into a problem that some would say is much larger than genetically modifying individual animals. You explore geoengineering, the climate, in order to combat climate disruption. And that really is a truly global problem, and a truly global solution. So what would that geoengineering look like?

One way to cool the planet could be to solar-geoengineer the climate through releasing sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere, like volcanoes do. (Photo: RPP Photos, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

KOLBERT: One of the really profound challenges of dealing with climate change is that carbon dioxide is not like a lot of other sort of more conventional pollutants, where if you stop pouring them into the air, they will drop out of the atmosphere and your problem will be, you know, after a certain amount of time, solved. Carbon dioxide hangs around, you know, for all intents and purposes forever. So if you got to a point where you said, okay, this amount of climate change is really, you know, a disaster, either humanitarian disaster or an ecological disaster, it would be extremely difficult to reverse that or, you know, get rid of it in a human timescale. And the only idea that people have come up with, scientists have come up with where you could actually reverse climate change, you often hear people talking about reversing climate change. But really, there's no way to reverse climate change except through solar geoengineering, where you would counter the effects of all the CO2 in the air by pouring another chemical compound, potentially sulfur dioxide, potentially calcium carbonate into the stratosphere, little tiny particles that would reflect, have a reflective quality would reflect sunlight back out to space and basically diminish the amount of direct sunlight that was hitting the earth. And that would have a cooling effect. And we know that this can be done. Because volcanoes do it. When you get a big volcanic eruption. It spews a lot of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere. And that creates these tiny little droplets that are called aerosols. And those reflect sunlight back to space, you get these fantastic sunsets, and you get cooling. It's temporary, because eventually that drops out of the stratosphere. But so you'd have to constantly replenish these particles. But that's the idea.

O'NEILL: And that would create the white sky that your book is talking about living under.

KOLBERT: Yes, exactly. One of the many potential side effects of, you know, trying to re-engineer the stratosphere is that it would change the reflectivity of the stratosphere in a way that would turn the sky you know from very blue to more whitish. So the first step first question that really needs to be answered is are we going to even allow experiments to go forward. If we don't allow even experiments to go forward then never know if it works or not.

Elizabeth Kolbert is a journalist and author who has contributed to the New Yorker for the last two decades. (Photo: John Kleiner)

O'NEILL: And among these questions, there is the scientific. And then there's also the ethical questions. There's the global conflict questions. There's all these different things that have to be a factor in making decisions.

KOLBERT: Yes, absolutely, it really brings to the fore. I mean, there are two ways that we're really messing around with what for lack of a better word I will call natural systems. And one of them is intentionally, and one of them is unintentionally. And, you know, climate change, as we've discussed, is the unintended side effect of industrialization and of living the way we do, and then we will have to decide, okay, do we want to intentionally intervene here we've created, there's so much damage that we need to try to intentionally do something, and that does raise a lot of different questions. But, you know, the sad fact is that we have unintentionally, these questions already are questions we should be asking, because, you know, what we're doing just the way we lead our daily lives here in the U.S. certainly is impacting people all around the planet, you know, including a lot of people who had very little to do with creating the problem. So the possibilities, you know, for global conflict over climate change, they're also very real. But I think that the idea of intervening intentionally raises that to a whole new level.

O'NEILL: And now, I think it is not inaccurate to say that your book really brings up a lot more questions than answers. What should we make of that?

In addition to Under a Whte Sky, Elizabeth Kolbert is the author of Field Notes from a Catastrophe: Man, Nature, and Climate Change and The Sixth Extinction, for which she won the Pulitzer Prize. (Image Courtesy of Penguin Random House)

KOLBERT: Well, I thought of making the epigraph of the book a quote from a British environmental writer and activist, a guy named Paul Kingsnorth, who I think has written some very interesting stuff. And he, I'll try to get the quote, as close as possible. He says, you know, at a time like this, I'm not really sure anyone has any useful answers, but we can try to raise useful questions. And I think that, that is what I'm trying to do. I think what I'm also trying to do with the book is really bring home how extraordinary the time that we live in is, you know, I don't think we've really fully come to appreciate that we live in an unprecedented moment, I mean, truly unprecedented in Earth history, where one species is changing the world at a remarkable rate, a rate, you know, equaled only by the great catastrophes in earth history, like asteroid impacts, you know, very, very fast by geological standards. It doesn't seem that way to us, you know, we go about our lives, we drive our cars, you know, we used to go to work, we used to go to restaurants, but all these things that are, you know, pumping CO2 into the atmosphere, changing the way that, you know, land is used, changing the surface of the earth, changing the atmosphere, we're now thinking of mining the deep sea. That will change the surface of the sea floor. We're just a remarkable creature that has this remarkable power to change the world. And now we're suddenly, not suddenly, but we're, it's dawning on us. Wow, some of these are really dangerous changes, I mean, really dangerous. And what are we going to do? And that gets a little bit back to the, you know, can we solve these problems with the same thinking that got us into them? Can we solve them at all? You know, these are really the big questions of our time, I think.

CURWOOD: That’s Elizabeth Kolbert, author of Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future speaking with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill.

Related links:

- More on the book, Under a White Sky (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- A passage from Under a White Sky as published in the New Yorker

- Find other books featured on Living on Earth (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Snarky Puppy, “Skate U” on Tell Your Friends, Ropeadope]

CURWOOD: Coming up – looking beyond the Headlines at some reluctance for offshore wind development in the Gulf of Maine. That’s ahead on Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Vasen, “Shapons Vindaloo” on Live At the Nordic Roots Festival” by A. Ferrari, NorthSide Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Satellite monitoring data from Brazil indicates that deforestation in the Amazon is up 43% over the April last year. These results come after Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro promised to curb deforestation at the virtual Climate Leaders Summit last month. (Photo: Quapan, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

And it's time for us to take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and dailyclimate.org. And when he's not looking behind those headlines for us, he's relaxing at his place there in Atlanta, Georgia, and he's on the line now I think. Hey there, Peter, how you doing? What you got for us?

DYKSTRA: I am here, I'm doing well, Steve. And we're going to go to a meeting held last month on Earth Day April 22, where President Biden brought together world leaders in a cyber summit to talk about the environment and climate change. One of those leaders was Brazil's President Jair Bolsonaro. He's been heavily criticized for allowing huge growth in the deforestation of the Amazon. And he pledged in that April 22 meeting to knock it off, to increase enforcement, and to make sure that the Amazon is better protected than it is.

CURWOOD: I have a feeling that there's a "but" to this, and that but is...

DYKSTRA: There's an awfully big but here, Steve. And that is that the April numbers from Brazil's own satellite monitoring show that April 2021 showed a 43% increase in deforestation over the month of April a year ago, 2020.

CURWOOD: Well, that's a lot of trees. Hey, what else do you have for us today, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Well, we shall see if the deforestation decreases in the Amazon, but in this country, President Biden has pledged to greatly increase clean energy, including offshore wind. But in the state of Maine, there's a Republican Representative named Billy Bob Faulkingham, who has filed a bill that would effectively ban offshore wind power in Maine state waters.

A lobster boat approaches the dock off the coast of Maine. Republican state lawmakers and fishing interests put forth a bill that would effectively ban offshore wind development in the state, citing fears over its impact on the lobster industry. (Photo: Paul VanDerWerf, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, Maine has done a lot of research though on offshore wind because it's kind of deep there and I believe the University of Maine has spent maybe the better part of a decade trying to figure out how you could put wind turbines out there that wouldn't get washed away in storms.

DYKSTRA: It can be done despite the deep waters in much of the Gulf of Maine. But representative Faulkingham, citing some exotic stats on the cost of wind development that I have a little trouble believing, he favours nuclear power and importing hydro power from Quebec. And obviously there are environmental concerns there. He says this is to protect lobstermen already under threat by warming waters. The representative told the Portland Maine Press Herald, quote, it is time to put a permanent halt to offshore wind development. He called it a "science project".

CURWOOD: Okay, Peter. Well, let's take a look now back in history. I'm staring, you're staring, what do you see?

DYKSTRA: Well, we have a happy 10th anniversary for Solyndra, a name many of us knew and a name many of us have forgotten. But in May 2011, this quiet failure in Obama's energy program became public. The Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit journalism center, reported that a half billion dollar Department of Energy loan guarantee to the solar panel manufacturer Solyndra had gone bad. Solyndra declared bankruptcy months later in September 2011, stranding over 1,000 employees and launching an absolute Republican field day for attacking not just Solyndra, not just Obama, but the entire notion of solar energy.

Solyndra, a solar panel manufacturer based in California, received half a billion dollars in federal Department of Energy loans before going bankrupt in 2011. (Photo: Jonathan Cutrer, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Of course, that Department of Energy loan guarantee fund also gave about a half a billion dollars in loan guarantees to one Elon Musk to get Tesla going up to scale. So for a fund that was designed to fund long shots, how would you say the balance is?

DYKSTRA: Well, certainly because Elon Musk hosted Saturday Night Live last week, he's certainly alive and well and still kicking. Certainly so is Tesla. But the other thing that gets me is imagine, just 10 years ago, when a half billion dollar scandal was a lot of money. But a half billion dollar scandal is not much in today's trillion dollar economy.

CURWOOD: Indeed not. Thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News thats ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Alright Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon!

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth web page, that's loe.org.

Related links:

- Chicago Sun Times | “Brazil’s Amazon Deforestation Surged in April After Pledges”

- Portland Press Herald | “Maine Fishing Interests Seek Total Ban on Offshore Wind Energy”

- The New York Times | “The Solyndra Mess”

CURWOOD: Just ahead, with a warming and drier climate the Colorado River is struggling to meet demand but first this note on emerging science from Casey Troost.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Note on Emerging Science: Biochar and Irrigation

A partially-burned forest after a fire in Norse Peak, outside of Tacoma, Washington. (Photo: Richard Droker, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

TROOST: Intense drought in the Western US is fanning the flames of record wildfires in recent years, but new research shows that fire can indirectly help conserve water in drought-prone areas. The key is biochar, a sort of charcoal-dirt made of burned plant remnants. A study from Rice University found new evidence that biochar can slow the flow of water through sandy soils. Sandy soils cover much of the American west and lock in less water than soils mixed with silt or clay. This is because of surface area: Water sticks to surfaces, and the more surface area there is, the harder it is to move. For example, take a big straw versus ten small straws. You might be able to drink the same amount of water with both, but the small straws’ extra surface area will make you work harder. For soil, sandy soils are the big straw. They have bigger particles and gaps than soils with silt or clay, and this can make for thirsty plants. Without enough surface area in the soil, the water runs off the field too fast, and farmers in places like Nebraska have to pump up more than their crops actually need. That’s part of the reason why agriculture alone swallows 80% of US water consumption. But biochar can help reduce wasted water and keep more water on the land.

Biochar is a type of charcoal formed by burning organic material in a zero- or low-oxygen environment. (Photo: Marcia O’Connor, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The researchers found that its unique shape breaks up the big spaces between sand particles, slowing down the water. And tiny pores inside each biochar particle absorb even more; under a microscope, it looks like a honeycomb. These new findings are great news for water conservation. The researchers found that farmers in certain parts of Nebraska can save nearly 40% of irrigated water by incorporating biochar into their sandy soils. And water isn’t the only benefit. The little pores in biochar also absorb atmospheric carbon, phosphorus, nitrogen, and other nutrients, and store them for plants to use. Just think - biochar is like a little lunch box and water bottle combined! That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Casey Troost.

Related link:

Read the full study here

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

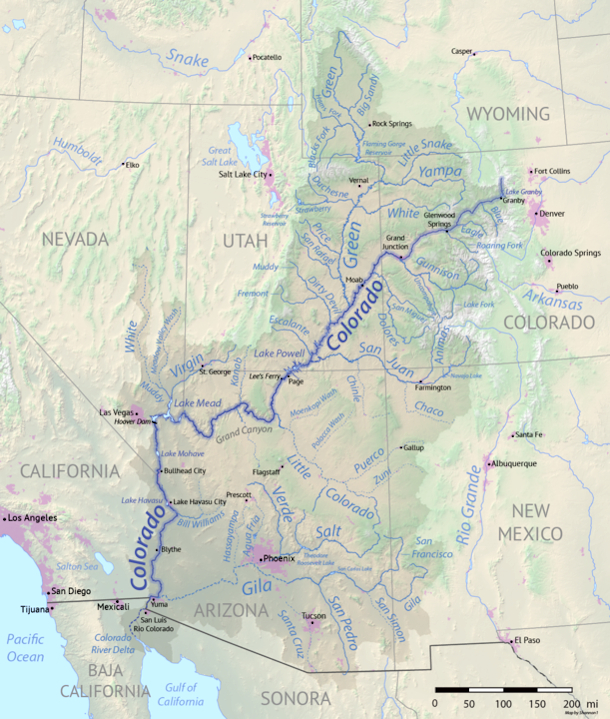

The Colorado River’s Dwindling Water Supply

The thick white “bathtub ring” at shrinking Lake Mead, which is impounded by Hoover Dam. (Photo: Ricardo Frantz on Unsplash)

CURWOOD: The Colorado river that carved the Grand Canyon and now quenches the thirst of much of the American West is parched in a “megadrought,” with two key reservoirs expected to drop to record low levels this year. Lake Mead behind the Hoover Dam is the biggest human made reservoir in the US and it’s now just 43% full. Our second biggest reservoir, Lake Powell behind the Glen Canyon dam, is even worse off at just 35 percent capacity. With forecasts that hot and dry drought conditions could persist for years, the odds now favor the federal government declaring a formal water shortage in the Colorado River Basin later this year. Reporter Luke Runyon covers the Colorado River Basin and is on the line now from station KUNC in Greeley, Colorado. Welcome to Living on Earth Luke!

RUNYON: Hi, thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So Luke Runyon, you cover the Colorado River Watershed as a beat, huh? What's the extent of the watershed?

RUNYON: So the Colorado River flows through seven US states. Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Wyoming make up the upper watershed. And California, Nevada and Arizona make up the lower watershed. It also crosses over the US-Mexico border and two Mexican states use water from the river as well. And it acts as a drinking water supply for some of the West's largest cities; when you think of Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Denver, they all pull water from the Colorado River. And it also acts as a really important agricultural irrigation water supply. You're looking at some of the most intensely farmed areas of the country: California's Imperial and Coachella Valleys use water from the Colorado River; the Yuma, Arizona area, which is kind of the "lettuce basket" of the country, that uses Colorado River water as well. So it's a really important water source for a large swath of the American Southwest.

Lake Powell is holding just 35% of its capacity. (Photo: Zetong Li on Unsplash)

CURWOOD: Wow, how big is the Colorado River flow when it's at its full-throated strength? Compare it to another major river for me, would you?

RUNYON: Well, it's actually, if you compare it to, like, the Mississippi River, it's a very small river. It, you know, it flows through some of the most arid reaches of the country. But we've tasked the river with a lot of different jobs. Because the area is so arid, the reliance on the Colorado River is huge. And there's just not enough water supply to go around. And so it's an intensely managed system in order to try and stretch it as far as we can.

CURWOOD: Now just how low today are the Colorado River water levels? We're speaking in May of 2021.

RUNYON: The Colorado River, you can kind of judge its health based on its two largest reservoirs. And this is Lakes Mead, and Lake Powell, which are in southern Utah for Lake Powell, and kind of the border between Nevada and Arizona, near Las Vegas, for Lake Mead. They are approaching record low levels. And that's because we've had essentially 20 years of above average temperatures in the basin, and below average flows on the whole over that 20 year period. And that's showing up in these reservoirs that are supposed to cushion between the really dry years. We're also seeing some changes in soil moisture, which is another thing, it's kind of like the hidden water bank. We always get so focused on surface water because we can see it, we can, you know, look at a river and know, oh, the river is high, or the river is low. But groundwater plays a huge role in the Colorado River Basin. And right now, soil moisture levels in parts of the Colorado River Basin are at the lowest that we've ever seen, and some much below the record. And you can kind of think of the ground as this giant sponge: when it's really dry, any new precipitation that falls, it's going to fill up that deficit that's left in the ground before it flows off into rivers. And so even a year where you have decent snowpack, you can see that snow not necessarily turn into a huge amount of water supply, because it's getting soaked up by that sponge in the ground.

CURWOOD: Now how much of the shortage in the Colorado River system is because of growing demand, that we have more and more people in places like Los Angeles and Phoenix and throughout the Southwest?

The Colorado River basin. Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Wyoming make up the upper watershed, while California, Nevada, and Arizona make up the lower watershed and two Mexican states use water from the river as well. (Photo: Shannon1, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

RUNYON: Demand definitely plays a role. But I think the biggest concern really is on the declining supply. In a lot of big cities in the West, demands have been flat, or in some cases have actually declined. And there are many different case studies of cities that have been able to grow while having their water demands either stay static or actually decline. The problem really is when you have the same amount of demand that you've had for a long time, but then the supply is shrinking. Those demands have to shrink along with that supply. And that's really the hard part. And those are the hard discussions that are going on in the basin right now, is, whose water supply should be curtailed in order for us to match the declining supply that we're seeing? And that's a really hard discussion to have, because we've built up massive cities and we've built up agriculture. We have all these expectations of what the river is is supposed to deliver to us and it just doesn't want to deliver that anymore, because of climate change and warming temperatures.

CURWOOD: So what are water officials on both, well, the regional as well as the national, federal level, saying they're going to do about this shortage?

RUNYON: It's not like there's one agency, or one overriding commission that makes all of the decisions on the Colorado River. It's managed by all of the people who, who depend on it. All of the various agencies and states, the federal government plays a role. And so it has to be collaborative by nature, because all of these various entities have to come to the table and decide who gets what amount of water. And they come to these agreements. And right now, all of these various entities are coming to the table, deciding how to implement old agreements and how to come up with new ones. And really, the driving question is, who has to use less water? The current agreement that the watershed is under is called the Drought Contingency Plan. It was passed in 2019. And really, it's kind of a band-aid to some of the past agreements that haven't been enough to halt the decline in some of these reservoirs. The Drought Contingency Plan lays out this series of cutbacks that Arizona, Nevada, Mexico and California have to take as Lake Mead declines. As the level of the reservoir gets lower, those states and the country of Mexico have said, we will take less water from the Colorado River.

Most of the water people take from the Colorado River quenches the thirst of crops like lettuce in Yuma, Arizona. (Photo: Tina Sibley, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, to what extent would the federal government be in a position to come in and, say, declare an official water shortage situation? I gather if the Interior Department were to declare that there is an official water shortage in the Colorado River Basin, it would trigger, I would think, some reductions, even some mandatory cuts. What's the status of that at this point?

RUNYON: We're looking at a very high likelihood of an official water shortage being declared in the Colorado River Basin later this year. That declaration is tied to the level of Lake Mead. And so when Lake Mead dips below a certain threshold, within an agreement, it says that the Interior Secretary will be able to declare an official water shortage. And it's a bold statement, saying, we don't have enough water to meet everyone's needs.

CURWOOD: So Luke, to what extent can water conservation practices help alleviate the shortage, bring things back from the break?

RUNYON: It depends on the type of water conservation practice that you're talking about. If you're talking about like a large, systemic conservation initiative, like installing a new water recycling plant in a large city, that can play a huge role in, you know, ensuring that that city has enough water to meet the really dry times ahead. You know, a lot of cities in the Colorado River Basin have put some effort toward getting people to remove their lawns because outdoor residential water use is some of the largest water usage in a large metropolitan area. So I think the individual decisions that people make play a really big role. But the Colorado River Basin is such a large, complex system, it really takes states, large governments, federal agencies coming together to manage this crisis. Because really, these issues are so much larger than just the individual decision.

CURWOOD: As I understand it, what, 70, 80% of the water in the Southwest goes to agriculture, to growing things, even some things that are not very water efficient, like rice, or hay. What are ways that agriculture could conserve water to help alleviate this, this shortage?

RUNYON: You can talk to a lot of farmers who say, yes, we need to figure out how to use water more efficiently. You know, we need to be looking at different types of infrastructure, different methods to irrigate, maybe even different crops to grow in order to be more water efficient. You're also starting to see some of the states talk about what they refer to as demand management. So these are programs that would essentially pay farmers not to irrigate, and send that water downstream for another use or put it into a reservoir for later storage.

Reporter Luke Runyon covers the Colorado River basin for KUNC and 20+ NPR stations in the southwest. (Photo: Courtesy of Luke Runyon)

CURWOOD: You know, given the effect that climate disruption is having on drought and, and water usage, what's the long term outlook for water supplies in the West and Southwest?

RUNYON: Yeah, and I wouldn't want somebody to hear this conversation and think that, you know, we're quickly approaching Mad Max-style water wars in the Southwest. But I do think that there is a certain level of alarm that you're hearing from those who pay really close attention to the Colorado River. You're starting to see a lot more scientists, you know, water managers, saying that this is a huge issue and it needs a lot of attention and it needs a lot of investment in order to make sure that, that we don't approach the level where we're having people fighting over water in the Colorado River Basin.

CURWOOD: Luke Runyon is a reporter with KUNC in Greeley, Colorado, who covers the Colorado River Basin. Luke, thanks so much for taking this time with me today.

RUNYON: Thanks, Steve.

Related links:

- KUNC | “With First-Ever Colorado River Shortage Almost Certain, States Stare Down Mandatory Cutbacks”

- The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation predicts at least 2 more dry years ahead for the Colorado River Basin

- About reporter Luke Runyon

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Peace” on Spirit, by Horace Silver, Jazz Legacy Productions]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Grace Callahan, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Natalie Seo, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. We bid farewell to our intern Paige Greenfield, thanks for your work, Paige! You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth