Oceans Losing Oxygen

Air Date: Week of July 9, 2021

A swirling green phytoplankton bloom in the Baltic Sea traces the edges of a vortex, July 18, 2018. Algae blooms now regularly cause dead zones in the basin. (Photo: Joshua Stevens and Lauren Dauphin / NASA Earth Obervatory)

Warmer water holds less oxygen than cool water does, so as the globe and the oceans heat up, they’re losing oxygen. The problem is heightened by pollutants like nitrogen and phosphorus, which contribute to oxygen-starved “dead zones” in the Gulf of Mexico and elsewhere. Denise Breitburg is a senior scientist with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center and explains to LOE’s Bobby Bascomb what declining ocean oxygen is doing to sea creatures, and what needs to be done to address the crisis.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb. As we talked about earlier in the program, one of the most far-reaching consequences of climate change is ocean warming. Higher ocean temperatures affect everything from fish health to hurricane strength, and worsen sea level rise. And warmer ocean temperatures are even changing the chemistry of the ocean itself by reducing the amount of oxygen in the water. Pollution is also depleting ocean oxygen. Here to explain is Denise Breitburg, she’s a Senior Scientist with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. Denise, welcome to Living on Earth!

BREITBURG: Oh, thank you.

BASCOMB: So Denise, what's going on here? How much have ocean oxygen levels declined in the last few decades?

BREITBURG: Well, since the 1970s, the open ocean has lost about 2% of its total oxygen content. That may not sound like a lot, but that's 150 billion tons of oxygen. And then during the same time, we have recorded occurrences of low oxygen in over 600 coastal sites around the world, places like estuaries and inland seas.

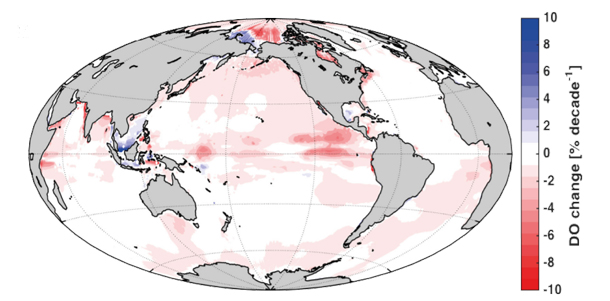

Dissolved oxygen changes in the oceans over the past five decades. While oxygen has increased in some locations, overall the world’s oceans are losing oxygen. (Image: Schmidtko, S., Stramma, L. and Visbeck, M., 2017. Decline in global oceanic oxygen content during the past five decades. Nature, 542(7641), p.335.)

BASCOMB: And how does that less oxygen actually affect ocean creatures? Can you give us a couple examples?

BREITBURG: The best way to think of the effect of oxygen decline on creatures that live in the ocean is by the old motto of the American Lung Association, which is "if you can't breathe, nothing else matters". So low oxygen affects the ability of organisms to survive in the ocean, it affects where they live. It affects where they're fished. And for microbes, it really affects how they influence the chemistry of the ocean. So when oxygen is really low microbes in the ocean will produce things like methane or nitrous oxide that are really potent greenhouse gases.

BASCOMB: And why are oxygen levels in decline?

BREITBURG: There are two main reasons. One is that the earth is getting warmer. Warm water can't hold as much oxygen as cool water can, and warm temperatures also make it much harder for oxygen from the atmosphere to mix into deeper water. The other problem is that we are discharging way too much nutrients into our coastal waters. You can think about nutrients as fertilizing a lawn; a little bit is you know, not damaging, it can stimulate growth. But as we put more and more nutrients in from sewage, from burning of fossil fuels, and from agriculture, we are growing way too much phytoplankton; way too much biomass is created. And as that decays, the decay process uses up oxygen.

BASCOMB: And then you're looking at dead zones?

BREITBURG: Right, they're dead zones when you think about where fish and crabs and things like that can live, they're not dead in terms of microbes. It's great habitat for microbes that live in the absence of oxygen or where oxygen is incredibly scarce. So basically, energy from the ecosystem that would be going into production of fish and corals and all those kinds of organisms that we normally think of living in the ocean, instead get shuttled into microbes.

A phytoplankton bloom in the Chesapeake Bay in 2014. (Photo: Joshua Stevens and Jesse Allen / NASA Earth Observatory)

BASCOMB: And you've studied the problem of dead zones in the Chesapeake. Can you tell me about some of the impacts that you're seeing there?

BREITBURG: In the Chesapeake Bay during summer, oxygen concentrations are really low in bottom waters in the middle of the bay, in some of the tributaries, and at nighttime, even in really shallow water. And when oxygen is low, things that can swim away do, and animals that can't avoid the low oxygen die, or they don't grow as well or they're more susceptible to disease where oxygen is really low in the dead zone. Instead of waters filled with fish and jellyfish and all kinds of animals swimming around, it's empty and silent.

BASCOMB: What about the very base of the food chain in the ocean, zooplankton -- how are they impacted by lower oxygen levels?

BREITBURG: Zooplankton will often avoid low oxygen if they can. But it's critical to their ability to use habitat and some new work that has been done out in the open ocean in some of these low oxygen areas shows that even small changes, just a small further decrease in oxygen can completely exclude these animals.

BASCOMB: How troubling is that? I mean, zooplankton, of course are eaten by tiny fish which are eaten by larger fish and so on up the food chain, until you get to whales and sharks at the very top.

BREITBURG: Low oxygen can completely change the way food webs operate. They can control whether things like zooplankton are available to fish to eat, they can control whether they are able to escape predators or become more sensitive. And we also really worry that for fish and other things that are targets of fisheries, low oxygen can actually make them more susceptible to becoming overfished.

Low oxygen levels cause fish kills in the Chesapeake Bay and other coastal waters that experience phytoplankton blooms. (Photo: Chesapeake Bay Program, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: And how might lower oxygen levels ultimately impact people that rely on fish for their subsistence or commercial fishermen?

BREITBURG: We really worry that low oxygen can make fisheries less sustainable and can have negative effect on fishing communities, especially ones that are very dependent on local resources. If you have a fishery that's, you know, highly industrialized, can move to where the fish are, they may be able to catch fish in spite of low oxygen, but even there, there's potentially a problem. If fish are avoiding low oxygen areas, they're becoming more concentrated in areas with higher oxygen which may be closer to the surface or if we think about the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, they can become really abundant around the edges of the dead zone. Fishers know how to target these areas. And so what oxygen can do is it can concentrate the fishing fleets and the fish or shrimp into the same area, make it easier to catch them. And then we really worry about overfishing.

BASCOMB: So it's literally like shooting fish in a barrel.

BREITBURG: Yeah, it can be like that.

Oysters are an important part of the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem and help clean the water, but they are particularly vulnerable to low oxygen, which appears to suppress their immune systems. (Photo: Steve Freeman, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, Denise, what can be done about this? I mean, what can we do to address this problem of declining oxygen levels in the world's oceans?

BREITBURG: There are two basic things that we need to do. The first is to reduce nutrients coming into coastal waters, from agriculture, from fossil fuel burning and from human waste. And these are all things that have real direct human health benefits if we take those steps as well as benefits to the ocean. So if we are doing a better job at sewage treatment that makes for a much cleaner environment that is less likely to cause health problems for humans. For agriculture, there are practices that can reduce the amount of nutrients nitrogen and phosphorus that are added to our waterways while still producing the food that the growing human population needs. The other major thing that we need to do is to take the steps needed to reduce the problem of global warming and reverse the trajectory that we're on.

BASCOMB: So stop the warming of the oceans, you know, that would go quite a long ways in addressing this problem.

BREITBURG: We absolutely need to stop the warming of the oceans, both for the sake of the oceans and for the sake of the human population that's on land.

BASCOMB: Denise Breitburg is a senior scientist with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. Thank you for taking this time with me.

BREITBURG: Thank you so much.

Links

Scientific American | “The Ocean Is Running Out of Breath, Scientists Warn”

Science | “Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth