July 9, 2021

Air Date: July 9, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Ocean Warming Speeding Up

View the page for this story

A study published in the journal Science finds that our earth’s oceans are warming 40 percent faster than the IPCC reported in 2013. This means rising sea levels, stronger, wetter and larger storms, and more intense droughts. Kevin Trenberth, Distinguished Senior Scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, CO, talks with Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood about these new scientific findings. (07:51)

BirdNote®: Black-footed Albatross, Graceful Giant

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Black-footed albatrosses are some of the most magnificent pelagic creatures off our shores. But as BirdNote®’s Michael Stein points out, though the adults may be glorious and graceful birds, the infants are kind of frumpy. (01:50)

Oceans Losing Oxygen

View the page for this story

Warmer water holds less oxygen than cool water does, so as the globe and the oceans heat up, they’re losing oxygen. The problem is heightened by pollutants like nitrogen and phosphorus, which contribute to oxygen-starved “dead zones” in the Gulf of Mexico and elsewhere. Denise Breitburg is a senior scientist with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center and explains to LOE’s Bobby Bascomb what declining ocean oxygen is doing to sea creatures, and what needs to be done to address the crisis. (08:38)

Oyster Shell Recycling

/ Kara HolsoppleView the page for this story

Fertilizer runoff can create massive algae blooms in water that suck up oxygen and creates dead zones for most other forms of life. The Chesapeake Bay is particularly vulnerable but as Kara Holsopple from Allegheny Front reports, restaurants in Pittsburgh are pitching in to help. (06:55)

Mother and Son: Sea Otter Bonding

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Mother sea otters spend a lot of time grooming their young pups. It’s a bonding experience as well as a matter of survival. Clean and well-groomed fur keeps these sea otters afloat on the coastal waters where they spend their entire lives. Living on Earth’s Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender narrates a precious scene of an attentive otter mom and her young pup. (02:18)

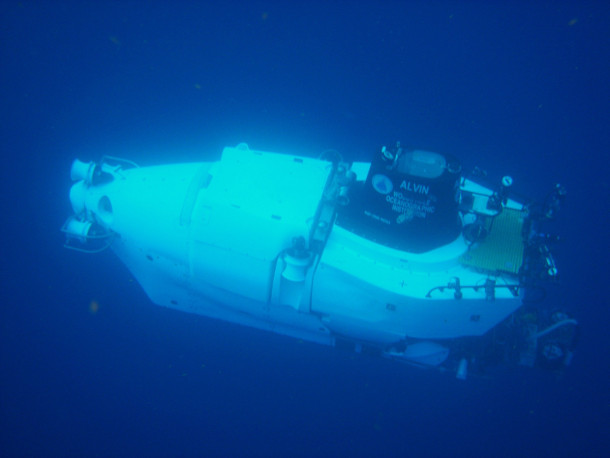

Note on Emerging Science: Deep-Sea Vehicle Alvin Reaches New Depths

/ Casey TroostView the page for this story

Oceanographers have gathered a lot of evidence on how pollution and climate change impact the world’s oceans. But knowledge of the way these factors come into play in the deep ocean has been limited. Now, upgrades to the deep-sea research submersible Alvin will put 99% of the ocean floor within reach of its crew. Living on Earth’s Casey Troost reports. (02:26)

Secrets of the Whales

View the page for this story

On Earth Day 2021, National Geographic released Secrets of the Whales, a video documentary miniseries that seeks to unravel the secrets of whale behavior and understand whale cultures of orcas, humpbacks, narwhals, belugas, and sperm whales. National Geographic Explorer and wildlife photographer Brian Skerry joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about the experience of filming this epic project and the breathtaking complexity of whale societies across the world. (16:13)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Denise Breitburg, Brian Skerry, Kevin Trenberth

REPORTERS: Kara Holsopple, Mark Seth Lender, Michael Stein, Casey Troost

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX this is Living on Earth

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Oxygen levels in the world’s oceans are in decline partly because climate change increases water temperatures.

BREITBURG: Warm water can't hold as much oxygen as cool water can, and since the 1970s the open ocean has lost about 2 percent of its total oxygen. That may not sound like a lot but that's 150 billion tons of oxygen.

BASCOMB: Also, we’ll take a look at the cultures of whales.

SKERRY: These charismatic ocean animals are showing behaviors that are really cultures, not unlike humans. So they are not only teaching their offspring the skills that they will need to survive, but they're teaching them their ancestral traditions, the things that matter to them.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

Ocean Warming Speeding Up

In September 2018 the unusually long duration of Hurricane Florence led to severe flooding in the Carolinas. (Photo: NASA, Wikimedia Commons CC)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

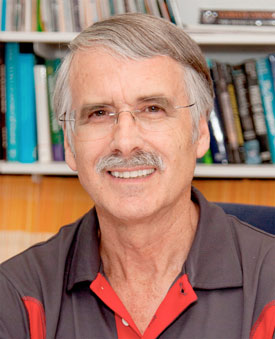

Research published in Science Magazine finds that the world’s oceans are getting warmer at a much faster rate than the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reported back in 2013. The latest research used updated scientific instrumentation and modeling to recalibrate past data. The oceans play a dominant role in the Earth’s weather in a number of ways, from brewing storms to creating El Niños. Warmer oceans lead to bigger, longer and stronger storms and it will take centuries for the seas to cool down even if emissions of heat-trapping gases such as carbon dioxide and methane are eventually reduced. Kevin Trenberth, is a Distinguished Senior Scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder and a co-author of the study. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

CURWOOD: So Kevin, bottom line is, is that the ocean is getting hotter, some 40% faster than what had been previously thought, huh?

TRENBERTH: That's correct. And especially in recent times. So the main period we talked about in the record in the paper, based upon the IPCC report was from 1971 to 2010. And of course, we can go right up to the present in the new record. And so the record, not only are the values higher, but there's clear evidence of an accelerating rate. So, the oceans are warming faster now than they used to be.

CURWOOD: Faster and faster. What does that mean, in terms of actual temperature rise?

TRENBERTH: A lot of the deep ocean is changing by very small amounts, so only a few hundredths of a degree Celsius and so the deep ocean is warming by very tiny amounts. The surface ocean as a whole has warmed by, a little over one degree Fahrenheit, and the air above the oceans has about five to 10% more water vapor. As a consequence of that the air is warmer, and it's moisturer. And it's best to think of it that way. Because one degree Fahrenheit produces air that can hold about 4% more moisture on average. And we're finding in general that this five to 10% number is about what we're seeing over the global oceans. So this is what feeds the storms, and leads to immediately a five to 10% increase in rainfall. But that increase in rainfall also means that the heat that went into evaporating the moisture in the first place is released, that heat gets released into the storm, and it can invigorate the storm. And so you can easily double that amount. So it can easily convert into 15 to 20% increase in rainfall. And some of the experiments that have been done using models of different kinds suggest that in the case of Harvey, for instance, that there was about a 30% increase in the rainfall as a consequence of the warming of the oceans and the climate change.

CURWOOD: So where are the temperatures rising the most in the oceans?

TRENBERTH: We have maps of that actually, and some of the biggest warming is occurring over the southern oceans. That's a region where there are strong winds and the heat gets carried down. It's also warming quite substantially throughout much of the Atlantic Ocean, and including the North Atlantic.

CURWOOD: What implications could this dramatic temperature acceleration that you're now able to observe, what does that mean for sea level rise?

TRENBERTH: So sea level has gone up by about 30 millimeters relative to the average, from 1970 to 2010. In recent times, we've had altimeters in space, that are measuring sea level, to millimeter accuracy. And so the rate of increase of sea level is about 3.1 millimeters per year. So if you think of 3.1 millimeters, think of a foot ruler, that's about 30 centimeters. And so this is a little over a foot per century, if you like to think of it that way. That's the current rate of sea level rise. And so we can estimate now how much sea level has risen from the expansion of the ocean.

Warming oceans can increase the intensity of storms. (Photo: Dr. DeNeo, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Gee, a foot per century doesn't sound very bad.

TRENBERTH: That's only a part of the sea level rise overall, of course. The other part, a slightly larger part, is the melting of glaciers and Greenland and Antarctica, which is contributing also to sea level rise. And, so, the total sea level rise is maybe three times that.

CURWOOD: And, now how are these rising ocean temperatures affecting our weather?

TRENBERTH: So some spots of the ocean get warmer than others because of the weather events over the past year. And one of the warmest spots in 2018 was off the coast of the Carolinas, which is where Florence developed. And that led to tremendous flooding and a very slow moving storm that caused a tremendous amount of problems in that area. The previous year, 2017, one of the warmest spots was in the Gulf of Mexico, where Harvey developed and indeed led to tremendous flooding in the Houston area. And we've been able to show indeed, that there's a direct relationship there between the heavy rainfalls and the ocean heat content.

CURWOOD: Whoa, so wait a second, we're talking about in the Paris deal keeping warming below one and a half degrees centigrade. So you know, my math is a little wobbly, but we're talking say two and a half degrees Fahrenheit, 2.7, maybe; we're getting a 15, 20% increase in storm strength, just from that one degree Fahrenheit, what would the world be like if we were to hit that target that's been talked about for Paris?

TRENBERTH: Well, this is indeed, what we're seeing around the world, is that the dry spots, the places where it's dry, things are drying out a little more, increasing the risk of wildfire, but then the moisture that is being evaporated, gets carried around and converges into the locations where the storms form. And so that's a key reason why that amplification occurs; rather than 5% change, you immediately get a 10% change. And then the lifetime of the storm is another key factor and the size of the storm is the other factor that can easily get you up to something like maybe a 30% change when you take all of those factors into account. And so the storms sort of reach out and grab all of the available moisture in the area, bring it into the storm and drop it down in the form of rainfall. And so we've got very good evidence that when it rains, it rains harder. And that's especially true along the east coast, and especially the Northeast.

CURWOOD: Yes, as you said, it’s been important to go back and look at data that was gathered in different ways and if you have gaps in data that makes things very difficult.

TRENBERTH: Yes, observations that are not taken are lost forever. We cannot go back and redo those.

Kevin Trenberth is a Distinguished Senior Scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research. (Photo: National Center for Atmospheric Research)

CURWOOD: You've been doing this research for a number of years. How do you feel about what we're seeing now?

TRENBERTH: Well, it's quite worrying. There’ve been a number of reports that have come out recently, some from the National Climate Assessment in the United States, and also the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and there’s a more complete IPCC report underway as a next major assessment as to what's going on on a worldwide basis. They have been consistently shouting out a warning that we're headed for, potentially an increase of two degrees Celsius, which has been a metric in the Paris Agreement, for instance, saying that we really should not get to that level if we possibly can, in terms of the global mean temperature increases, because going along with that is a whole lot of very disruptive effects and potentially dislodging ecosystems. And there are many consequences that get progressively worse. The sort of things we've already talked about increase substantially. And about that level, food shortages and water shortages could become very widespread. So we need to avoid that if we possibly can. In addition, we need to plan for these things and build resiliency.

BASCOMB: Kevin Trenberth is a distinguished senior scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood.

Related links:

- Science Magazine | “How fast are the oceans warming?”

- More about Kevin Trenberth and his work

[MUSIC: Dr. Lonnie Smith, David “Fathead” Newman “Tropicalia” on Boogaloo to Beck, Scufflin’ Records 2003]

BirdNote®: Black-footed Albatross, Graceful Giant

The Black-footed Albatross uses wind currents and shifts in air pressure to fly for hours over the Pacific Ocean while barely needing to flap its wings. (Photo: Tom Grey)

BASCOMB: We stay at sea for today’s BirdNote®, and catch up with some of the most magnificent pelagic creatures off our shores. But as Michael Stein points out, though the adults may be glorious and graceful birds, the infants are kind of frumpy.

BirdNote®

Black-footed Albatross, Graceful Giant

[SOUND OF WAVES AND SEA BREEZE AND CALL OF THE BLACK-FOOTED ALBATROSS]

STEIN: Just a couple of dozen miles off the Pacific Coast, immense, dark birds with long, saber-shaped wings glide without effort above the wave-tops. These graceful giants are Black-footed Albatrosses, flying by the thousands near the edge of the continental shelf.

[SOUND OF WAVES AND SEA BREEZE AND CALL OF THE BLACK-FOOTED ALBATROSS]

Albatrosses arc and coast over the ocean for hours with hardly a flap of their wings. Making the most of wind currents and shifts in air pressure, these wondrous seabirds seem to levitate over the water.

[SOUND OF WAVES AND SEA BREEZE AND CALL OF THE BLACK-FOOTED ALBATROSS]

Albatross parents travel hundreds of miles to collect food for their nestlings, which are raised one at a time and grow to be massive. (Photo: Eric VanderWerf, US Fish and Wildlife Service, CC)

Black-footed Albatross numbers peak off the coast in summer. Many adults return to the Hawaiian Islands during our winter and spring, to court and nest on sandy islands.

In Hawaiian waters, the Black-footed Albatross collects squid and masses of flying-fish eggs with its long, hook-tipped bill. Adult birds may fly hundreds of miles at sea to provide food for the single, goliath nestling, which looks more than a little like a portly, gray, recumbent version of Big Bird.

[BLACK-FOOTED ALBATROSS ADULT WITH BEGGING NESTLING]

I’m Michael Stein.

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Sounds of the Black-footed Albatross provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Call of the adult and begging call of the young recorded by W.V. Ward.

Ambient track provided by Kessler Productions

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2005-2017 Tune In to Nature.org October 2017

Narrator: Michael Stein

http://birdnote.org/show/black-footed-albatross-graceful-giant

BASCOMB: For pictures soar on over to the Living on Earth website, loe dot org

Related links:

- The “Black-footed Albatross, Graceful Giant” story on the BirdNote® website

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology: About the Black-footed Albatross

[MUSIC: Rikard From, “It’s an Upright Thing”, Rikard From]

BASCOMB: Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line anytime at 617-287-4121 that’s 617-2870-4121. Our email address is comments@loe.org, comments@loe.org. And visit our webpage at loe.org.

Coming up – Warmer ocean temperatures mean less oxygen in the water, a challenge for many marine species.

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green, and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

Oceans Losing Oxygen

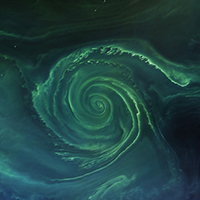

A swirling green phytoplankton bloom in the Baltic Sea traces the edges of a vortex, July 18, 2018. Algae blooms now regularly cause dead zones in the basin. (Photo: Joshua Stevens and Lauren Dauphin / NASA Earth Obervatory)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb. As we talked about earlier in the program, one of the most far-reaching consequences of climate change is ocean warming. Higher ocean temperatures affect everything from fish health to hurricane strength, and worsen sea level rise. And warmer ocean temperatures are even changing the chemistry of the ocean itself by reducing the amount of oxygen in the water. Pollution is also depleting ocean oxygen. Here to explain is Denise Breitburg, she’s a Senior Scientist with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. Denise, welcome to Living on Earth!

BREITBURG: Oh, thank you.

BASCOMB: So Denise, what's going on here? How much have ocean oxygen levels declined in the last few decades?

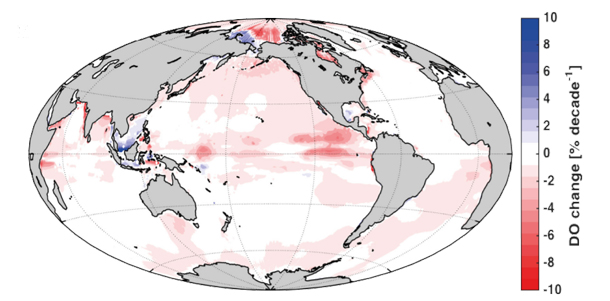

BREITBURG: Well, since the 1970s, the open ocean has lost about 2% of its total oxygen content. That may not sound like a lot, but that's 150 billion tons of oxygen. And then during the same time, we have recorded occurrences of low oxygen in over 600 coastal sites around the world, places like estuaries and inland seas.

Dissolved oxygen changes in the oceans over the past five decades. While oxygen has increased in some locations, overall the world’s oceans are losing oxygen. (Image: Schmidtko, S., Stramma, L. and Visbeck, M., 2017. Decline in global oceanic oxygen content during the past five decades. Nature, 542(7641), p.335.)

BASCOMB: And how does that less oxygen actually affect ocean creatures? Can you give us a couple examples?

BREITBURG: The best way to think of the effect of oxygen decline on creatures that live in the ocean is by the old motto of the American Lung Association, which is "if you can't breathe, nothing else matters". So low oxygen affects the ability of organisms to survive in the ocean, it affects where they live. It affects where they're fished. And for microbes, it really affects how they influence the chemistry of the ocean. So when oxygen is really low microbes in the ocean will produce things like methane or nitrous oxide that are really potent greenhouse gases.

BASCOMB: And why are oxygen levels in decline?

BREITBURG: There are two main reasons. One is that the earth is getting warmer. Warm water can't hold as much oxygen as cool water can, and warm temperatures also make it much harder for oxygen from the atmosphere to mix into deeper water. The other problem is that we are discharging way too much nutrients into our coastal waters. You can think about nutrients as fertilizing a lawn; a little bit is you know, not damaging, it can stimulate growth. But as we put more and more nutrients in from sewage, from burning of fossil fuels, and from agriculture, we are growing way too much phytoplankton; way too much biomass is created. And as that decays, the decay process uses up oxygen.

BASCOMB: And then you're looking at dead zones?

BREITBURG: Right, they're dead zones when you think about where fish and crabs and things like that can live, they're not dead in terms of microbes. It's great habitat for microbes that live in the absence of oxygen or where oxygen is incredibly scarce. So basically, energy from the ecosystem that would be going into production of fish and corals and all those kinds of organisms that we normally think of living in the ocean, instead get shuttled into microbes.

A phytoplankton bloom in the Chesapeake Bay in 2014. (Photo: Joshua Stevens and Jesse Allen / NASA Earth Observatory)

BASCOMB: And you've studied the problem of dead zones in the Chesapeake. Can you tell me about some of the impacts that you're seeing there?

BREITBURG: In the Chesapeake Bay during summer, oxygen concentrations are really low in bottom waters in the middle of the bay, in some of the tributaries, and at nighttime, even in really shallow water. And when oxygen is low, things that can swim away do, and animals that can't avoid the low oxygen die, or they don't grow as well or they're more susceptible to disease where oxygen is really low in the dead zone. Instead of waters filled with fish and jellyfish and all kinds of animals swimming around, it's empty and silent.

BASCOMB: What about the very base of the food chain in the ocean, zooplankton -- how are they impacted by lower oxygen levels?

BREITBURG: Zooplankton will often avoid low oxygen if they can. But it's critical to their ability to use habitat and some new work that has been done out in the open ocean in some of these low oxygen areas shows that even small changes, just a small further decrease in oxygen can completely exclude these animals.

BASCOMB: How troubling is that? I mean, zooplankton, of course are eaten by tiny fish which are eaten by larger fish and so on up the food chain, until you get to whales and sharks at the very top.

BREITBURG: Low oxygen can completely change the way food webs operate. They can control whether things like zooplankton are available to fish to eat, they can control whether they are able to escape predators or become more sensitive. And we also really worry that for fish and other things that are targets of fisheries, low oxygen can actually make them more susceptible to becoming overfished.

Low oxygen levels cause fish kills in the Chesapeake Bay and other coastal waters that experience phytoplankton blooms. (Photo: Chesapeake Bay Program, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: And how might lower oxygen levels ultimately impact people that rely on fish for their subsistence or commercial fishermen?

BREITBURG: We really worry that low oxygen can make fisheries less sustainable and can have negative effect on fishing communities, especially ones that are very dependent on local resources. If you have a fishery that's, you know, highly industrialized, can move to where the fish are, they may be able to catch fish in spite of low oxygen, but even there, there's potentially a problem. If fish are avoiding low oxygen areas, they're becoming more concentrated in areas with higher oxygen which may be closer to the surface or if we think about the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico, they can become really abundant around the edges of the dead zone. Fishers know how to target these areas. And so what oxygen can do is it can concentrate the fishing fleets and the fish or shrimp into the same area, make it easier to catch them. And then we really worry about overfishing.

BASCOMB: So it's literally like shooting fish in a barrel.

BREITBURG: Yeah, it can be like that.

Oysters are an important part of the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem and help clean the water, but they are particularly vulnerable to low oxygen, which appears to suppress their immune systems. (Photo: Steve Freeman, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, Denise, what can be done about this? I mean, what can we do to address this problem of declining oxygen levels in the world's oceans?

BREITBURG: There are two basic things that we need to do. The first is to reduce nutrients coming into coastal waters, from agriculture, from fossil fuel burning and from human waste. And these are all things that have real direct human health benefits if we take those steps as well as benefits to the ocean. So if we are doing a better job at sewage treatment that makes for a much cleaner environment that is less likely to cause health problems for humans. For agriculture, there are practices that can reduce the amount of nutrients nitrogen and phosphorus that are added to our waterways while still producing the food that the growing human population needs. The other major thing that we need to do is to take the steps needed to reduce the problem of global warming and reverse the trajectory that we're on.

BASCOMB: So stop the warming of the oceans, you know, that would go quite a long ways in addressing this problem.

BREITBURG: We absolutely need to stop the warming of the oceans, both for the sake of the oceans and for the sake of the human population that's on land.

BASCOMB: Denise Breitburg is a senior scientist with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. Thank you for taking this time with me.

BREITBURG: Thank you so much.

Related links:

- Scientific American | “The Ocean Is Running Out of Breath, Scientists Warn”

- Science | “Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters”

[MUSIC: Ma Kru, “Palabras” on Tu Mission, self-published]

Oyster Shell Recycling

Chesapeake Bay oysters wait to spawn. (Photo: Kara Holsopple, The Allegheny Front)

BASCOMB: The Chesapeake Bay is routinely inundated with fertilizer runoff from the surrounding watershed in parts of Pennsylvania and Maryland. The result is algae blooms that suck up oxygen in the water and create dead zones for most other forms of life in the Bay. Oysters are particularly vulnerable but as Kara Holsopple of The Allegheny Front reports some local groups have come up with a novel way to help oysters recover.

[AMBI RESTAURANT KITCHEN]

HOLSOPPLE: Jessica Lewis says shucking an oyster is like picking a lock...

LEWIS: You press down and then you just wiggle, pop it open and, the abductor muscle right there. You clean that.

HOLSOPPLE: Lewis is the executive chef of Spirits & Tales at the Oaklander Hotel in Pittsburgh. She runs a small knife around the sides of a closed oyster shell...

[NAT POP SOUND]

Jessica Lewis, executive chef of Spirit & Tales at the Oaklander Hotel in Pittsburgh, prepares oysters. (Photo: Kara Holsopple, The Allegheny Front)

LEWIS: You can't really muscle through it. You clean under it and see all that liquor? This one’s got a lot of liquor in it.

HOLSOPPLE: That’s the salty ocean water still inside the shell, and it makes the oyster slide out smoothly...into your mouth...

LEWIS: That's perfect. I'm going to take this one right here.

HOLSOPPLE: Lewis says they go through about three to four hundred oysters here a week...from the East and West coasts. This oyster is from Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay...and its top and bottom shell are going back there…

[AMBI OUTSIDE NOISE/TRUCK]

Lewis and her staff toss the spent shells in a 35 gallon barrel with a screw-on lid, located in the trash area on the ground floor of the building.

LEWIS: So, nobody likes to recycle the oyster shells because there's flies everywhere and it's nasty. Gross

LEWIS: But we're doing something good. Let's get out of here.

[AMBI OUTDOORS/TRUCK OUT]

HOLSOPPLE: About once a month a truck picks up the old shells from this and six other participating restaurants in Pittsburgh, and drives them more than 250 miles to a staging area just across the Chesapeake Bay Bridge in Maryland.

From there, the oyster shells from Pittsburgh, and ones collected from Maryland, Virginia and the D.C. area are taken to a site at the University of Maryland’ Horn Point Laboratory in Cambridge, for processing.

[AMBI OUTDOOR]

KING: “So here you’re looking at about 7K tons of clean shell…”

HOLSOPPLE: Karis King is with Oyster Recovery Partnership, a nonprofit which works to increase oyster numbers in the Chesapeake Bay. We’re standing at the base of a mountain of gray shells.

They’ve been dumped into a machine that’s like a modified potato hopper, which sorts the shells...

[NAT SOUND OF SHELLS DUMPED]

And washed with water from the nearby Choptank River...a major tributary of the bay. Smaller fragments of broken shell fall away as a conveyor belt deposits the half shells into wire cages or piles where they’re cured for a year.

[NAT SHELL ON BELT]

Then they’re ready to go on to the next phase of the recycling chain...

KING: even with all the shell that we do recycle, and that we also purchase from shucking houses, we still don’t have enough to do large scale restoration, at the rate that we could.

[AMBI OUTDOORS OUT]

HOLSOPPLE: That’s because of the scale of the problem. Stephanie Alexander manages the Horn Point Lab oyster hatchery.

ALEXANDER: When John Smith sailed up in the 1600s he was running aground on oysters...

HOLSOPPLE: Alexander says that’s before these waters were overharvested, before there was agricultural runoff and soil erosion from development...

ALEXANDER: We've pretty much wiped the oyster out to less than 1 percent of historic levels. So we started this restoration effort where we're using a hatchery to produce spat on Shell to put back into the bay so we can kind of help jump start Mother Nature.

HOLSOPPLE: The concept is pretty simple: Scientists here at the lab produce baby oysters from adults harvested from the bay, nurture the microscopic larvae with a custom algae diet, then get them attach to the recycled, treated oyster shells...that’s the ‘spat on shell.’

In practice, it’s a lot harder than it sounds…

[AMBI LAB]

Ben Malmgren is an intern here, a student from St. Mary's College of Maryland.

[NAT PLACING OYSTERS]

MALMGREN: Right now we're placing the oysters out on the spawning table where we are going to simulate river conditions that are ideal for spawning.

[NAT WATER]

HOLSOPPLE: The saltiness and temperature of the water in the shallow black basins has to be just right. Malmgren places the oysters in a grid formation, so it’s easier to separate the males from the females…

MALMGREN: Because if we just let them spawn out on the table all these eggs are gonna go down to the into the drain. So once we see a female and we'll we'll know she's a female by she'll clap her top and bottom shell together and we'll see a plume of eggs come out and kind of look like Splenda like in a cup of coffee.

HOLSOPPLE: Then he’ll pull the females off the table, where they’ll continue to spawn in a tub. Those eggs will be fertilized with the sperm collected from the male oysters. But the oysters aren’t cooperating today…Left to their own devices, it could take hours...

MALMGREN: It's a lot like just watching a pile of rocks but can be exciting when they all start going.

[AMBI LAB WATER OUT]

[AMBI LAB]

Stephanie Alexander manages the Horn Point Lab oyster hatchery. (Photo: Kara Holsopple, The Allegheny Front)

HOLSOPPLE: Even in the lab, nature is in charge. Stephanie Alexander says it was a slow summer...a lot of rain meant the adult oysters have lived with lower salinity levels, and they’re stressed. Out in the bay, the water is warmer, meaning the spat on shell might have a harder time growing that second shell, and over the years, forming the clusters that create oyster reefs.

ALEXANDER: When one thing gets out of whack everything else is going to kind of follow. So we're trying to get the oysters back into balance so then hopefully everything else will follow as well.

HOLSOPPLE: Over the last 2 decades, the lab and Oyster Recovery Partnership have planted over 8 billion oysters on the bottom of the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries, with the help of other partners like the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Throughout the summer spat on shell are released from a boat on sites where they’re most likely to survive. And Alexander says that’s critical…

ALEXANDER: Oysters are the vacuum cleaners or the kidneys of the bay and they just suck the water in, they decide if it's food or not food. But no matter what it is that will remove it from the water column and that's how they vacuum the bay up and clean it.

HOLSOPPLE: Because of this superpower, oyster aquaculture is a best management practice identified by the regional partnership that oversees cleaning up the Chesapeake Bay.

Some of the spat raised at the Horn Point Lab will make its way to oyster farmers, and those are the oysters on a half shell that are served in restaurants. But the majority of the spat will help rebuild oyster reefs, creating habitat for fish, and restoring the ecosystem.

[RESTAURANT AMBI]

BACK IN PITTSBURGH, Jessica Lewis is educating diners and trying to convince other Pittsburgh restaurants to join the oyster shell recycling effort that feeds the conservation work... to see the value in giving back...

LEWIS: With all this like climate change going on and all those scary things it's like a bright light shining through...that we did something good.

HOLSOPPLE: Her pitch: Every shell counts.

BASCOMB: Kara Holsopple’s story comes to us courtesy of State Impact Pennsylvania, a collaboration of public media outlets covering Pennsylvania's energy economy.

Related links:

- Hear this story on the Allegheny Front website

- Learn more about oyster restoration in the Chesapeake Bay

- This story was produced in partnership with StateImpact Pennsylvania

[MUSIC: Arturo Sandoval “Blues in F” on My Passion For The Piano, Crescent Moon Records]

Mother and Son: Sea Otter Bonding

Sea otters give birth in the water and can spend their whole lives without ever leaving the water. To care for her young, a mother sea otter places her newborn on her belly, grooming it from head to tail. (Photo: (c) Mark Seth Lender)

BASCOMB: Oysters and other shellfish can be a staple food for many marine species including sea otters. Living On Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender has our story.

Mother and Son

Southern Sea Otter

Elkhorn Slough, Monterey Bay

© 2021 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

In the narrowed channel, slack tide, a mat of kelp or weed or salt grass floats along, without a notion of its own, captured by the absent-minded tug and turn of eddies at slack tide between the sand bars. It drifts, closer. Then shifts, further. Catching in a spiral of water turning, turning until…

Recognition!

Mother and Son Sea Otter!

The sea otter has the thickest fur of any animal. Such dense fur allows for insulating pockets of air, keeping them warm and helping them stay afloat as they lie on their backs. When ungroomed, dirty hairs will clump together, losing captured air, so grooming is a matter of survival. (Photo: (c) Mark Seth Lender)

The baby is newborn, one week, maybe two. Round and wet, unable to fend for himself. Cannot care for himself. His mother washing, scrubbing, rubbing, combing every inch of him. And when she finishes one end, working from the long spiky fur of his tail, she turns him on the Lazy Susan of her belly and starts all over the opposite way, from his sweet wet face on down. He opens his eyes. He has a sleepy look. She props him up on a cushion of water and dives, and comes back with a clam she breaks open and divides but does not share with him.

He is too young. But soon…

When they are not foraging or grooming, sea otters are often resting. To keep themselves from drifting out to sea, they will wrap themselves in kelp and hold on to each other as they snooze. This group of resting sea otters is called a “raft.” (Photo: (c) Mark Seth Lender)

Then sea clam will be food to him, the taste he will follow all his life. When he is older and stronger and heavy enough he will learn to follow her down and down to the cloudy bottom, and recognize the shapes and smells and take a stone and crack the shell. There will be a lot to learn. He is lucky. She will as mother otters do take the time to teach him.

As much, and as long, as he needs.

BASCOMB: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Read Mark's Field Note for this essay

- Learn more about author and photographer Mark Seth Lender’s work

- All you need to know about sea otters!

- Special thanks this week to Kayak Connection of Moss Landing, CA

[MUSIC: Gary Burton, “Clarity” on Next Generation, by Julian Lage, Concord Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – The potential for the deep sea submarine, Alvin, to explore the bottom of the world’s oceans.

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[MUSIC: Ruby Braff, “I Got Rhythm” on Ruby Braff (The Concord Jazz Heritage Series), by George Gershwin/Ira Gershwin, Concord Records]

Note on Emerging Science: Deep-Sea Vehicle Alvin Reaches New Depths

The ALVIN submersible begins its descent to the bottom. 2006 May 21. (Photo: Gavin Eppard, WHOI, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It's Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb. Just ahead we’ll take a deep dive into the culture of whales but first this note on emerging science from Casey Troost.

TROOST: Oceanographers have gathered a lot of evidence on how pollution and climate change impact the world’s oceans. But a newly upgraded research submersible will deepen their understanding even more.

This September, engineers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Falmouth will finish seven years of upgrading and testing the deep-sea research submersible Alvin. First created in 1968, Alvin has been completely stripped down and upgraded many times over.

ALVIN in 1978, a year after first exploring hydrothermal vents.(Photo: NOAA Photo Gallery)

The newest round of upgrades outfit the vessel with a third sampling arm, better cameras, a reinforced cabin, ballast spheres for stabilizing, and many other improvements. The upgrades will improve the quality of Alvin’s research and enable it to descend more than a mile deeper than it was previously able. Alvin’s reach will extend from less than 70% of the seabed to 98%, bringing the submersible into a group of less than ten others in the world that can carry scientists that far. But one of the most intriguing possibilities with the new and improved Alvin is that it will able able to enter the Hadal Zone, where undiscovered wildlife is coming into contact with human pollution.

The Hadal Zone extends from nearly four miles below the surface to the very bottom, roughly. While this region is unique for its isolation and hostility to most life, it plays a crucial role in carbon cycling for the ocean above.

You see, carbon in the form of waste, like whale carcasses and dead plankton, descends through the ocean to feed scavengers, bacteria, and fungi living below. But the same gravity that feeds the Hadal zone also exposes it to trash and chemicals. Already scientists have found toxic microplastics and PCB chemicals in the bodies of important scavengers.

Venturing four miles down, Alvin will just scratch the surface of the Hadal Zone. But this extra distance will help scientists keep better track of pollution, and its impacts. Not to mention new forms of life that wait in the depths.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Casey Troost.

Related links:

- Learn more about Alvin and its history

- If you’re interested in submersibles, you can subscribe to the National Deep Submergence Facility newsletter

Secrets of the Whales

A mother Humpback Whale with her calf in the waters off of Rarotonga, Cook Islands along with two escort males. Humpbacks in this region spend summers feeding in Antarctica, then migrate to the South Pacific to places like the Cook Islands where they have their calves and spend time in the warm, protected waters here. (Photo: Brian Skerry)

BASCOMB: A recent 4 part National Geographic video series, Secrets of the Whales, takes a deep dive into the culture of several whale species.

[HUMPBACK WHALE SONG]

From the ever evolving song of humpback whales...

[HUMPBACK WHALE SONG]

... To the unique way Orcas in Patagonia beach themselves to catch unsuspecting seals, or how narwhals know when to be silent to avoid predators in their migration.

All of these are learned behaviors, some passed between individuals and many taught to young whales by their mothers. Brian Skerry is a National Geographic photojournalist. He spent 3 years filming the series and joins me now. Brian, welcome to Living on Earth.

Orcas in New Zealand follow a unique hunting technique: taking stingrays off the bottom - sometimes in very shallow water. (Photo: National Geographic for Disney+/Kina Scollay)

SKERRY: Thank you so much, Bobby. It's a pleasure to be here.

BASCOMB: So, a theme that comes up again and again in this series is culture: that whales have distinct cultures. And not just between different species of whales, but between different pods or families. Broadly, how is culture expressed in whales?

SKERRY: Well, that is the essence of Secrets of the Whales. You're absolutely right. When I created this, I saw this as a game changer that the latest and greatest science was revealing that these charismatic ocean animals are showing behaviors that are really cultures, not unlike humans. My friend, Dr. Shane Gero, who's a sperm whale biologist, he defines it this way. He says behavior is what we do, culture is how we do it. So for example, most humans eat food with utensils, that would be behavior, but whether you use knives and forks or chopsticks, that is culture. So what we see in whales, you know, you might have a family of Orca that live in New Zealand, and their preference for ethnic food is stingrays. And they figured out how to eat those there. And the ones in the Norwegian Arctic, like to eat herring, and they figured out how to predate on herring. And the ones in Patagonia like seal pups, and they are the only ones in the world who have that strategy. They not only figured out this stuff, which is culture, but they pass it on to their children. So they are not only teaching their offspring the skills that they will need to survive, but they're teaching them their ancestral traditions, the things that matter to them. Whales have unique dialects. Sperm whales that Shane studies in the Eastern Caribbean, he's identified about 24 families that all speak the same dialect or language, and they belong to a clan. But they don't intermingle with other sperm whales that might come into those waters that speak another language. I think we can look at culture from a number of perspectives. But it's clear that like humans, they are doing things differently and what they know about their regions, their geographic location is unique to them. And that's what they celebrate.

Orca hunting rays in the waters off of the North Island in New Zealand. (Photo: Brian Skerry)

BASCOMB: And during your time in New Zealand with orcas there, there was a moment in the series where you were invited to share in the spoils of their hunt. Can you tell us about that experience?

SKERRY: I can. This was certainly one of the most extraordinary moments of my career of four decades of exploring the ocean. We worked in 24 locations collectively for this series worldwide over three years. And I had just come from six weeks in the Canadian Arctic and I had about 10 days in New Zealand. I was working with a researcher Dr. Ingrid Visser, who is the orca expert, lives in New Zealand, understands these animals. But again, you can never predict when something is going to happen. And we got lucky this one day, we heard about this, we drove three hours to get there, got in the boat, went out, found the orca, they were hunting in shallow water. I got in the water and started swimming towards them. And lo and behold, here is this adult female swimming towards me with a stingray actually hanging out of her mouth. My mind is on overload now, I'm thinking, I can't believe this. And then she drops it. So I'm thinking, oh man, you know, it's over.

She just gonna keep swimming. And I swim down to the bottom and I knelt on the sandy floor next to the dead stingray just laying there. And then out of the corner of my right eye, I see this orca coming back, and she swings behind my back, I lose sight of her for a moment. And then she emerges on the left side of my view, she swings around directly in front of me. And now we're staring at each other with a stingray between us. And she's looking at me and looking at the ray looking at me looking at the ray as if to say, "Well, are you going to eat that"? And when I don't go for it, then she very gently just bends over, picks it up in her mouth and lifts it up in front of me. And then she turns and begins sharing her food with another member of her family. You know, I don't think I fully processed what was occurring until after. That night over dinner, I started to think about just how remarkable that was. I talked recently with James Cameron about this. And he said, well you know, cultures do this. They share food. It's it's an offering. Very possibly that's what's going on. And you know, for me, I've had so many extraordinary moments with wildlife over the years. But this was right at the top of the list. It was really something very, very special.

National Geographic photographer Brian Skerry travels to Norway's remote fjords for a chance to capture new orca behavior. (Photo: National Geographic for Disney+/Luis Lamar)

BASCOMB: Yeah. And there's a cameraman right there so the viewer can watch this whole scene and you're wearing a black wetsuit. And I gotta wonder, does the orca just think you look like a skinny whale who maybe need some help?

SKERRY: Maybe, I mean, it's very possible. Who's to say? These are animals that share food, that's what they do. They catch a ray and then they turn around and one will hold it in their teeth in their mouth and another one will come over and take a piece off. So you know, I mean, it's very possible she was thinking, come on, join in the feast with us.

BASCOMB: The second part of your series is about humpback whales and you focus a lot on the sophisticated ways that they have of communicating across really vast distances. The males make up a new song each year that can travel thousands of miles. Can you tell us more about that?

SKERRY: Yeah, I call it the "American Idol" of the sea. It's a bit of a singing competition where, as you described, these males will compete every year at the beginning of the year with a tune, and then one tune gets to be the winning tune. And they adopt it and everybody sings that same song, pretty much. They might add little bits and pieces here and there, but they essentially pass it across the entire ocean. It's been described in scientific papers as the horizontal transmission of culture. Now, the interesting thing is that it's always been believed that the humpback whale song sung by the males is something to do with mating, that they are attracting females the way that a bird would attract a mate with its song. And there very well may be truth to that. But I've talked to researchers who have spent decades studying the humpback whale song, and I asked them what percentage of the time do you actually see a female come over and pair up with a male? And I forget the exact number, but it was something like 0.001%. So it doesn't get seen that often.

Humpback whales undergo one of the longest migrations of any mammal on Earth - over 6,000 miles. (Photo: National Geographic for Disney+/Adam Geiger)

Now, might it be that the collective number of males that are singing in a given place are attracting the females to those waters, and then they can do their courtship and mating and so forth? Perhaps, but I wonder, they're creating these very lyrical, 20 minute-long songs, and to be in the water next to them and to hear it is awe inspiring. It resonates your body, and maybe a little mystical, but I wonder, is there other information encoded in that message? Might it be like an Aboriginal song line that they're including some cultural elements of that song? Is it purely just to attract a mate? Or are they weaving in stories of their ancestors? Maybe that's a little bridge too far. Maybe that's a limb that some scientists won't go out on. But the bottom line is, we've been studying these animals for decades, we don't fully understand. I think there's a lot more secrets out there that, you know, need to be revealed in the time ahead. So hopefully, we'll figure that out.

BASCOMB: Yeah, it's amazing. And you know, we've been talking about male humpback whales. But I have to say, I think the females are really just as amazing. Can you talk to us please about the sacrifice they make each year when they have a calf and and the tremendous journey that they make with their babies?

SKERRY: Absolutely. You know, humpback whale mom invests a great deal into her calf. It's a year-long gestation period. And then for the first year of that life, it is learning everything that it needs to know from mom, it is joined at the hip. There up nuzzling next to its chin, and going along next to its eye, and then nursing underneath. It's such a tender moment to go out in the morning and one of these tropical locations like the Cook Islands, or Tonga, go into a quiet little Cove and then slip in the water. And just at the edge of visibility, you see this tenderness, this absolute love that's being shared by the mom and calf. And then as you say, they have to make this epic journey. There's new science that's come out just maybe in the last year or so that reveals that humpback whale moms whisper to their babies when they're traveling through areas where predators might be so they don't give away their location. So again, I think there's just so much richness to these bonds, these relationships. And again, so much of that we don't fully understand as well.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I was really struck by the fact that the mothers will feed their babies something on the order of more than 100 gallons of milk each day without eating themselves, they go for months and months without eating and are still nursing the babies just a tremendous amount of milk. It's amazing.

A group of humpbacks approach biologist Nan Hauser and National Geographic photographer Brian Skerry while on assignment for Planet of the Whales. (Photo: National Geographic for Disney+/Hayes Baxley)

SKERRY: It is, and that's how that calf grows. But think about the impact on that mom's body. I mean, the humpback baby is gaining weight every day, but she's losing it. So by the time it's ready to make that journey, she must be exhausted, you know, she doesn't have any energy. And now she has to make this epic migration to the feeding grounds and look after her calf and protect it from predators and all of those things. So you make a good point. She is deeply invested in that next generation. And it's it's a huge sacrifice, indeed.

BASCOMB: And you can see why they're obviously so invested. You know, we've heard stories of mothers losing their babies, they die for some reason or other, and pushing them through the water for just days and days, maybe even weeks, just unable to let go. You can see why after such an investment.

SKERRY: Of course, and we've captured that in the orca episode where in the Norwegian Arctic, it was Thanksgiving Day. You know, I've been working for National Geographic for almost 25 years and I travel eight or nine months a year but this was the first time I had been away from my own family on Thanksgiving Day. So I woke up that morning and I was thinking about my family at home eating turkey and celebrating and wishing I was home, but I got on the boat with my wetsuit and we went out and we saw this family of orca moving very purposely through one of the fjords. I was able to get in the water and see this funeral procession, this mom carrying it's dead baby and all the other members of the family sort of protecting the mom and calf and, you know, you see this grief, there's no other way to interpret that I think then mourning. And it was very emotional for me to be able to see that. But clearly, these animals have empathy and share grief and joy. And I think that's the message of Secrets of the Whales is that if we can see our planet, the ocean, through the lens of culture through the lens of these animals that have rich societies, then maybe we change our view of our connection to the natural world and maybe protect this beautiful planet on which we live.

A baby beluga smiles at the camera. Belugas are the only whale that can use their lips to form different shapes to communicate. (Photo: National Geographic for Disney+/Peter Kragh)

BASCOMB: Gosh, I sure hope so. This series also documents the formation of a surprising cross species adoption between lost Narwhal, a youth, and a pod of beluga whales. What exactly happened there? And what does that tell us about the culture of whales?

SKERRY: Yeah, thats a really special situation. And these are two polar species that have some similarities. But generally, you're not seeing them in that kind of close proximity. I think that is quite unique. And I think it speaks to the empathy and the accepting nature of these beluga whale families. I mean, clearly, they know that that's not one of their own. But yet they saw this narwhal that was alone, and just made it part of the family. They adopted it as one of their own. And, I mean, how wonderful is that? I think this is one of the messages that I've sort of taken away. You know, I spent three years working on this. As I've processed a lot of these moments that we witness in the series, it occurred to me that I've been reminded of things that I already knew, and that is that community matters, that family matters, that the whales make time for each other. A sperm whale for example, these are matrilineal societies led by the older, wiser females, they spend most of their life in the deep ocean foraging for squid. Life in the ocean is hard, but yet every day or every couple of days, they make time to come together and socialize. You see them rolling around and enjoying each other's company, reaffirming their family bonds. And for me to reflect back on this was to be reminded of how important social creatures are, that humans and whales can't do it alone. We need each other, we need family, we need community, and that that alone can bring us the greatest joy in life.

A narwhal's tusk is a long, hollow tooth that usually only develops in males. Its full function is still a mystery. (Photo: National Geographic for Disney+/Thomas Miller)

BASCOMB: It's a beautiful message. Well how important is it, do you think, to protect not just whale species, but whale cultures? So maybe some sperm whales in one place are doing okay, but if the resident pod and Dominica for example were to die out, what would be lost with them?

SKERRY: Well, that is a wonderful question and nobody has ever quite asked that. And I think it is immensely important. My friend, Dr. Shane Gero, who studies the sperm whales in Dominica, he wrote an op ed for the New York Times a few years ago, called the Loss of Whale Culture, and he specifically cited Dominican whales. He said that they are on a 3% annual decline because of anthropogenic stresses, they get entangled in fishing gear, they get hit by ships. And he argued that historically, biologists would look at that and say, you know, while tragic, it is not the end of the world because even if those whales go away, other sperm whales will come in and fill that niche. But what he says is no, what those whales know about those waters, the seamounts, the canyons, where the good food is, all the things that make them unique, would be lost. I think the loss of whale culture is an important aspect that gets lost in the bigger equation here, but in the way that we want to preserve human culture, we should want to preserve animal culture as well.

Marine biologists Shane Gero and Asha DeVos eavesdrop on sperm whale conversations with a hydrophone. They are listening for dialects that differentiate whale populations. (Photo: National Geographic for Disney+/Luis Lamar)

BASCOMB: It's really like our shared heritage.

SKERRY: It is, absolutely. You know, there's a great quote in my book from Henry Beston, in a book he wrote called the Outermost House about Cape Cod, and I won't get the quote, right, but he basically says that these other species that we share this planet with, they are not our underlings. They are not our brethren, necessarily. They are independent nations that we are traversing this journey on earth with, and therefore we must have equal respect.

A family unit of Sperm Whales socializing underwater in the waters off of the island of Faial in the Azores. (Photo: Brian Skerry)

BASCOMB: What do you hope your audience takes away from this series? What's your goal here?

SKERRY: I guess my hope, on a very basic level is that everybody enjoys it that it's entertaining and that they're happy to learn something about whales. But if I could have a bigger wish, it would be that audiences begin to see our planet a little bit differently. If we can look at whales, and as a result the ocean, and as a result our planet through that lens of culture, understanding that these highly cognitive, sentient animals are living in the ocean, that they have rich ancestral traditions, they are doing things much the way that we do, that maybe we will see our planet and our connection to it in a different way. And that maybe we will change our detrimental behaviors to the planet as a result of that. So that would be my grander hope. And that maybe without overtly being about conservation, that it could change the way we do things.

Sperm whales prefer to hunt for squid far beneath the surface. They routinely stay an hour below and can explore as deep as 10,000 feet. (Photo: National Geographic for Disney+/Luis Lamar)

BASCOMB: Brian Skerry is a National Geographic explorer and marine wildlife photographer. Brian, thank you so much for taking this time with me and for this wonderful series.

SKERRY: Thank you so much, Bobby. It's a real pleasure.

National Geographic Explorer and wildlife photographer Brian Skerry (Photo: Courtesy of Brian Skerry)

Related links:

- Stream Secrets of the Whales | Disney+

- Brian Skerry’s official website

- Read More on the Dominica Sperm Whale Project

[MUSIC: Taj Mahal, “When I Feel the Sea Beneath My Soul” on Sun Rise, by Taj Mahal, Geffen Records (Rereleased by Sony Music)]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Anna Canny, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Joshua Siracusa, and Tivara Tanudiaia and Jolanda Omari. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to Kayak Connections of Elkhorn Slough.

You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth.We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer.

I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth