Sheltering with Thoreau in the Age of Crisis

Air Date: Week of August 20, 2021

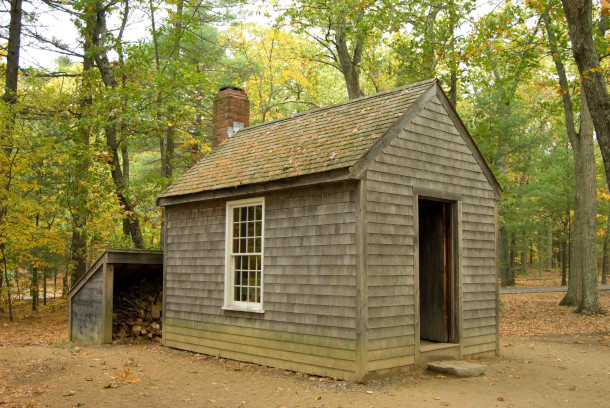

At Walden Pond, Thoreau developed his voice as a writer and generated much of the journal material that would later become the nature writing classic Walden. (Photo: Ashok Boghani on Flickr)

The COVID-19 pandemic brought the world to its knees and slowed the pace of life for many of us. For writer David Gessner, this era of retreating to our homes brought to mind one famous expert in social distancing, Henry David Thoreau. In his book, “Quiet Desperation, Savage Delight: Sheltering with Thoreau in the Age of Crisis,” David looks to Henry David as a guide to living through a pandemic, a time of racial reckoning, and a climate crisis, and he joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss.

Transcript

DOERING: The COVID-19 pandemic brought the world to its knees and slowed the pace of life for many of us. For writer David Gessner, this era of retreating to our homes brought to mind one famous expert in social distancing, Henry David Thoreau. In his book, “Quiet Desperation, Savage Delight: Sheltering with Thoreau in the Age of Crisis,” David looks to Henry David as a guide to living through a pandemic, a time of racial reckoning, and a climate crisis. David, welcome back to Living on Earth!

GESSNER: Thanks. It's great to be here again.

DOERING: Well, could you please introduce us to Henry David Thoreau for listeners who might not be familiar with his work?

GESSNER: Yeah, the big moment in Thoreau's life was in 1845. On July 4, his personal Independence Day, when he went to the woods, in Concord, Massachusetts, near where he lived not far from home, and squatted on Ralph Waldo Emerson's land. He kept journals, he explored the natural world, and he developed his voice as a writer there. That voice would find full flower in the book Walden, which many of us were forced to read in high school; some of us were bored by it, others had our lives changed by it.

DOERING: You mentioned being forced to read Walden in high school. You also in the beginning of your book, you write about how Henry David Thoreau ruined your life.

GESSNER: Yeah.

DOERING: Could you set that up? And could you read that passage for us?

“Quiet Desperation, Savage Delight: Sheltering with Thoreau in the Age of Crisis” reexamines Thoreau during the pandemic. (Image: Courtesy of David Gessner)

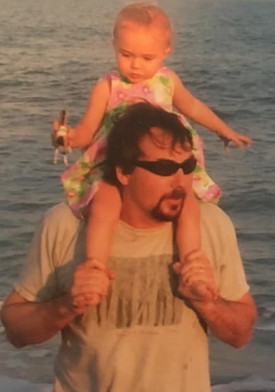

GESSNER: I would be happy to. The very beginning of the book, it starts like this: [READING] 16 years ago, when our daughter was just a baby, my wife and I took her on a trip to Walden Pond. As we approached the place where Henry David Thoreau's cabin once stood, with my daughter riding up on my shoulders, I said to her, "That's where the man lived, who ruined your father's life." Ruined in a mostly good way I meant. I discovered Walden when I was 16 and never quite recovered. I began to question the values of the system I found myself in. "The life that men praise and call successful is but one kind," Thoreau wrote, and I hollered, amen. In this way, Thoreau was like a more profound, less musical version of getting stoned and listening to Pink Floyd. But the effect was more lasting. I began to keep a journal in high school, and I keep one to this day. After college, the sentences from Thoreau's book, were still rippling outward through my life, affecting the choices I made. To hell with law school or any normal career, I would become a writer, I would value solitude. And I would move to my very own Walden.

DOERING: Can you tell me more about that idea that you had during this pandemic, this unprecedented time, David, why revisit Thoreau during the pandemic?

GESSNER: It was a weird string of coincidences really, for me. I had rebuilt the writing shack in my backyard on a tidal marsh in North Carolina that I built on my 50th birthday, but had been destroyed. In hurricane Florence, it flooded and basically floated out to sea. And I was rebuilding it that January before the pandemic. And I also, I was reading a biography of Thoreau by Laura Walls, great new biography. And I was thinking about self reliance and pulling back and being less busy. And then the pandemic hit. And I had this shack to retreat to. And I really took it as an opportunity to slow down. And I've always been interested in my own backyard, which is a salt marsh, which connects me to the Atlantic and the greater world. But I really studied it and I started to study the clapper rails, these birds in my backyard, and fiddler crabs. And it was so strange that this time of supposed isolation was a time movement and migration in the animal world. And you were seeing these flocks of birds come over. So like a lot of people, I rediscovered my own backyard and Thoreau if nothing else, is kind of the patron saint of discovering one's own backyard.

DOERING: So of course, I know that you're not new to observing nature, David, but I'd love to hear more about how sheltering in place really shaped your habits in the salt marsh that you call home.

Gessner’s daughter rides on his shoulders at Walden Pond, a moment Gessner recounts in the opening of his book. (Image courtesy of David Gessner)

GESSNER: Yeah, I think that the biggest thing for me was realizing that it wasn't just a casual thing. It was a discipline. Thoreau famously said, if you take a walk in the woods, and you have village thoughts, if you're thinking about your Things To Do List, your you know what you've got to do tomorrow, and not having Woods thoughts. You're not really walking in the woods. And I started to, you know, there were many great blue herons out on the marsh and I would watch them and I would see their patience, which isn't like kind of a groovy easy patience. It's waiting, waiting, waiting and then hitting, because it's effective, because it works. So I really, you know, I paid lip service to this stuff over the years, and I've talked about how, you know, we should try to be less anthropocentric and beyond ourselves. But what I was starting to see is, it's a discipline.

DOERING: So learning one's own backyard, part of your project here, it's not all birds and butterflies and wonderful things. In your case. It actually involved understanding this terrible legacy of racist terrorism in your hometown of Wilmington, North Carolina. What happened and what kind of reckoning is happening or still needs to happen?

GESSNER: Well, in 1898, before what was soon known as America's only coup, Wilmington was a majority black town. And it was a kind of cosmopolitan town because it's a port town. And it was actually a place where African Americans held political office held jobs on the police force. And where African Americans from elsewhere would come to Wilmington as kind of a refuge, a place to feel safe. Well, that all ended in November of 1898, when the minority white ruling class fired up the white lower class, essentially, and had a violent overthrow of the government. That legacy continues to this day in Wilmington, where it's because not only did they kill up between 80 and I think 400 people, they also exiled many others. So suddenly, this this place that had been a refuge became a nightmare, basically, and that legacy has continued to this day. Gradually, the history is being acknowledged, you know, our George Floyd protest, had another layer to them guess, as many towns do. But here we were in the south. So adding that to the just intense mix of kind of polar opposites of the year where we have the solitude, this isolation, and suddenly we're just so connected, not just to the place, but to history.

DOERING: So you mentioned in your book that Henry David Thoreau doesn't simply isolate himself from the world, he engages with it, how do you feel that he can help us meet the challenges of our current times?

Thoreau spent his time at Walden Pond in a 10x15 feet hand-built cabin, writing journals, reading, and observing nature. The above is a replica. (Photo: Ryan Taylor on Flickr)

GESSNER: So you know, Thoreau wasn't a hermit. He was famously a part of his neighborhood. In a way, Walden is just a response to people yelling down to him from the road, what the hell are you doing down there? He says, here's what I'm doing. And Laura Walls said, Thoreau didn't go to Walden to escape the world, but to confront it. You know, Civil Disobedience, which is not the full title, but it's how we know his famous essay, outlines his night in jail when he refused to pay tax that would support the Mexican War, but also slavery and the extension of slavery. And it was just one night in jail. It wasn't a great hardship. But symbolically, it had huge impact on thinkers from Martin Luther King to Gandhi. And it was because he said, that one could nonviolently resist what one deemed wrong. And he stuck to that throughout. So we think of him as the hermit at Walden. And he did go to Walden on July 4, but on a July 4, nine years after he went to Walden, he was in Framingham, Massachusetts with an upside down hanging American flag and another speaker who was burning the constitution and he was railing against slavery and in a classic Thoreauvian fashion, he kind of poo pooed the strict abolitionists because they were part of a group. But he individually, vehemently opposed slavery and was one of the only public supporters of John Brown after the rebellion that was a prelude to the Civil War basically.

DOERING: David, there's a passage in your book that explores how Henry David Thoreau provides some insight for this time of racial reckoning that we're in now. Could you read that passage?

GESSNER: Sure. [READING] What are we willing to give up to try and affect the change we want? Are we willing to sacrifice our private pleasure for the public good? Are we willing to interrupt our oh, so precious lives? It is dangerous business leaving the woods behind. It is scary out in the streets. Of course, it is more complicated than that, in at least one case, the ideas that inspire those on the streets, were born in the woods. I'll let Martin Luther King have the last word. He writes, "I became convinced that noncooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good. No other person has been more eloquent and passionate in getting this idea across than Henry David Thoreau. As a result of his writings and personal witness, we are the heirs of a legacy of creative protest. The teachings of Thoreau came alive in our civil rights movement. Indeed, they're more alive than ever before. Whether expressed in a sit in, at lunch counters, a Freedom Ride into Mississippi, a peaceful protest in Albany, Georgia, a bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. These are outgrowths of Thoreau's insistence that evil must be resisted, and that no moral man can patiently adjust to injustice."

While sheltering, Gessner further acquainted himself with the clapper rails in his salt marsh backyard. (Photo: Tom Murray on Flickr)

DOERING: It's remarkable how much of an impact Henry David Thoreau had on Martin Luther King and the way he was thinking about nonviolence and standing up against injustice.

GESSNER: Yeah. And you know, one interesting thing is people put Thoreau down and say, well, that was just one night in jail and it's just symbolic. Well symbols matter. And Thoreau in a way was famous for taking small things. Like he saw some red ants doing battle with black ants and he talked about a great war that was occurring. So in a way, that was a real part of what Thoreau did, and he saw the large and the small.

DOERING: One of the things that you discuss in your book is the impermanence of things that we call home, you know, grieving changes on the local scale, like the death of your writing shack, but also on a global scale with climate change. What insights does Thoreau have to offer on this, do you think?

GESSNER: Well, I just read a passage, it's not in the book, about how when a friend dies, you know, we die too, and how gradually, it starts to kind of pull away our core. And in the middle of the summer, a very close friend of mine, Brad Watson, who's a Great Southern writer, who I know, he was a National Book Award finalist, but he never really got his due, I felt, died suddenly of a heart attack. And for me, Thoreau lost his brother early on. And, you know, it always felt like he was looking for that one close friend who he could be completely honest to and trust in. And for me, that was a first loss of a peer. And that, and the events of the world that you're describing, and the climate, you know, I mentioned all the fires and the hurricanes, it can wear a spirit down. And I guess, on a large scale, I would say, Thoreau's looking to a world beyond the human world is vital, but on a smaller scale, recognizing the vital importance of the political, but at the same time, having carved out your private existence. You know, I actually have a chapter in there, not about Thoreau, but Montaigne, who said famously, the French writer from the 16th century, first essayist, he famously said, “we almost have a back shop to call our own”. So in a way, the pandemic year is perfect for that. It's so political, for obvious reasons. We had an election going on, I would come back from listening to bird calls, to listen to CNN, in my house, right and it was such a fraught year, but to keep you know, and to fight the political fights, and that's important, but to also keep that back shop, that place separate from there, where you're not overrun with the noise and clamor, and you have your own space, whether that's a shack, a walk you go on, a room in your house, a place, a garden in the neighborhood, just someplace apart, where you can refuel and renew yourself.

DOERING: David Gessner is the author of Quiet Desperation, Savage Delight: Sheltering with Thoreau in the Age of Crisis, and teaches at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. Thank you so much, David.

GESSNER: Thank you. I always love talking to you guys. And this was great.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth