August 20, 2021

Air Date: August 20, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

UN Report Charts Possible Climate Futures

View the page for this story

Scientists are once again sounding the alarm about the climate emergency, with part one of the 6th Assessment Report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC. Hundreds of experts collaborated to bring together the best science on past, present, and future climate change. Zeke Hausfather is a climate scientist and contributor to the most recent IPCC report, and he joins Host Jenni Doering to unpack the UN climate report. (11:19)

The Long and Winding Road to Green Infrastructure

View the page for this story

The $1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill includes some green measures to address and invest in crumbling American infrastructure. But climate and environmental justice advocates say much more is needed now from a much larger budget reconciliation package that’s in the works. Rachel Cleetus of the Union of Concerned Scientists joins Host Paloma Beltran to discuss where the bipartisan bill falls short on green investments and what’s needed in the budget reconciliation bill. (10:41)

Drought Threatens Migratory Birds

/ Erik NeumannView the page for this story

Every year, over a million birds migrate to several National Wildlife Refuges along the Oregon-California border. But this year unprecedented drought and low water levels pose a serious threat to the survival of several migratory bird species. Erik Neumann from Jefferson Public Radio has the story. (04:40)

Note on Emerging Science: The Beetle That Can Survive Being Eaten

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

For most insects, getting eaten by a frog is the end of the road. But a unique water beetle species can survive the perils of stomach acids and a lack of oxygen and pop out of the frog’s rear end unscathed. Living on Earth's Don Lyman reports on how an ecologist at Kobe University in Japan studied this beetle’s ability to defy death by digestion. (01:53)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Paloma Beltran discuss environmental fallout from the geopolitical standoff in the South China Sea. They also talk about how floods are washing away Black history in a Maryland cemetery, and in the history calendar, it’s 60 years since President Kennedy designated Cape Cod National Seashore. (04:30)

Sheltering with Thoreau in the Age of Crisis

View the page for this story

The COVID-19 pandemic brought the world to its knees and slowed the pace of life for many of us. For writer David Gessner, this era of retreating to our homes brought to mind one famous expert in social distancing, Henry David Thoreau. In his book, “Quiet Desperation, Savage Delight: Sheltering with Thoreau in the Age of Crisis,” David looks to Henry David as a guide to living through a pandemic, a time of racial reckoning, and a climate crisis, and he joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss. (13:51)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

210820 Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Rachel Cleetus, David Gessner, Zeke Hausfather

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman, Erik Neumann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran

Looking to Henry David Thoreau for guidance in difficult times

GESSNER: I was thinking about self-reliance and pulling back and being less busy. And then the pandemic hit. And I really, really took it as an opportunity to slow down. So, like a lot of people, I rediscovered my own backyard and Thoreau if nothing else, is kind of the patron saint of discovering one's own backyard.

DOERING: Also, severe drought threatens migrating birds in the Pacific Northwest.

SEUS: We’re taking what precious water is here and trying to accumulate it all into one spot to save 60-70,000 birds that perished last year that could be proportionately more than that this year.

BELTRAN: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

UN Report Charts Possible Climate Futures

Working Group I of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has released their portion of the 6th Assessment Report, which focuses on the physical science aspect of global warming. (Photo: Ania Mendrek, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BELTRAN: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Paloma Beltran.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Scientists are once again sounding the alarm about the climate emergency, with part one of the 6th Assessment Report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC. Hundreds of experts collaborated to bring together the best science on past, present, and future climate change. Dr. Zeke Hausfather is a climate scientist and contributor to the most recent IPCC report, and he joins us now. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Zeke!

HAUSFATHER: Thanks. It's great to be here.

DOERING: So I know that there are a whopping 4000 pages in this report. But I wanted to start by zooming way out. What are the most important takeaways from this IPCC report?

HAUSFATHER: So the most important takeaway at the top level is that, you know, there's an immense amount of scientific consensus at this point on some basic points about climate change: that it's real, it's caused by us, it'll be bad if we don't do anything about it. But we still have the power to decide how much warming the world experiences. But beyond that, it is a summation of the state of climate science. And there's a lot of new things that are reflected in this report that have changed over the last decade, you know, we have more certainty on the human role in warming. The report makes it very clear that our best estimate of the human contribution to the warming the world has experienced is pretty much all of it. About 100% of the warming the world has experienced is due to human activities according to the new report. It also unclouds our climate crystal ball in a really important way. So there's a concept in climate science called climate sensitivity. And what climate sensitivity refers to is essentially how much warming you get if you increase the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. And the reason that's a little bit uncertain is because there's a lot of feedbacks in the earth system. You know, if you increase the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere, you get more evaporation, you get more water vapor in the air, water vapor itself is a greenhouse gas and it traps more heat. You know, you get ice melting, revealing darker surfaces that absorb more sunlight. And so all these different types of feedbacks play together to determine how much warming the world experiences. And for a long time, there's been a range that climate scientists have given essentially, saying, if you double the amount of co2 in the atmosphere, you'll get somewhere between 1.5C, and 4.5C global average warming. That was the range given in 1979, in the Charney Report to the Carter administration, that was also the same range given in 2013 in the last major IPCC report. So you know, 30 years, and that range has remained fiendishly large, but what this IPCC report does for the first time is meaningfully narrow that range, and they say, you know, now we think if you double the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere, you end up with somewhere between 2.5 and 4 degrees warming globally. So that's half the uncertainty that we previously had in this range. And that's a really important advancement. And so narrowing this range is both bad in terms of less likely to have low amounts of warming and good in that some of the worst case scenarios now seem a little less likely.

DOERING: So Zeke, you're actually one of the reports, many contributing authors, what specific area did you work on?

HAUSFATHER: So, my research is cited in a number of areas of the report, the place I directly worked on in the report was on evaluating the performance of old climate models. So we looked at all of the climate models that have been published between 1970 and the early 2000s. And we look to see, you know, what did those models say would likely happen in the years after they were published, essentially, how much warming did they project, and then how much warming actually occurred in the real world. And it turned out that a lot of these climate models did a really good job at predicting what actually happened. We looked at 17 different climate model projections. Of those, 11 were indistinguishable from the rate of warming that happened in the real world. And the ones that missed off, about half of them were a little too low, and half of them were a little too high. And you know, this is really impressive, especially for the early models, you know, the first models published in the early 1970s. At the time, scientists didn't have a really good sense of what was happening to the world's temperatures, they hadn't gone around the world and digitized all these old logbooks and weather station records. And were relying mostly on a small number of temperature measurements from the northern hemisphere. And so in the early 70s, a lot of scientists thought that the world was actually slightly cooling at the time and had been for the last decade or two. And so essentially, what they were saying is, you know, we think this cooling trend is going to reverse, and the world is going to warm by 0.6 degrees centigrade by the year 2000. And that turns out is exactly what happened. You know, granted, the world wasn't actually cooling at the time as they thought, you know, we have better data now. And you know, the temperatures were mostly flat and starting to rise in the early 70s. But the fact that they predicted the amount of warming, you know, spot on is really impressive, and a testament to the fact that, you know, our climate models are getting the fundamentals right.

United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres described the 6th Assessment Report from the IPCC as “a code red for humanity”. (Photo: Faces of the World, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: To what extent do you think we've really grasped this different world that we're now seeing?

HAUSFATHER: I think, in some ways, what's happened over the last few years has made it much clearer for people than it used to be. You know, we used to talk about climate change as a problem for our children and our grandchildren. But with increasing heat waves, with increasing floods, which are due to higher amounts of water vapor in the atmosphere due to warming, massive wildfires ravaging the West Coast and you know, smoke covering the entire country at times now, the last few years have brought climate change home in a way that makes people realize that this is not a problem for our children and grandchildren. This is a problem that's affecting us today. And it's affecting us already. And you know, that's at 1.2 degrees Centigrade warming. And so it helps people see you know, just how much worse it can get if if we don't take action to cut our emissions.

DOERING: Right. I mean, I think UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres really called this IPCC report a "code red" for humanity. Could you break down for us how within reach is a lower emissions path at this point? And how does it compare with what people like to call "business as usual"?

HAUSFATHER: So that's a great question. You know, a decade ago, the world was in a really bad place as far as our climate goes, you know, global emissions had increased by 30% in just the past decade. And it seemed like we were heading toward a future where coal dominated the 21st century, and we might double or even triple our emissions in the next 80 years. Thankfully, things have started to change over the last decade, global coal use peaked at back in 2013, you know, clean energy has has largely become cheap, you know, prices of solar panels have fallen by a factor of 10 in the last 10 years, battery prices have fallen by a factor of 10, wind prices have fallen by a factor of three. And so we've started sort of flattening the curve of future emissions. You know, it seems like now we're entering a long plateau of emissions under policies that are in place today. But that still would lead us to, you know, somewhere around three degrees warming by the end of the century, under current policies. And as I mentioned, there are these uncertainties in climate sensitivity and carbon cycle feedbacks. So we certainly can't rule out four degrees warming or even more in the current policy world, even though our best estimate is three. And a three degree world is also not one we want to live in, it would be, you know, really hard for a lot of human systems to deal with, particularly in poorer countries where they don't have access to air conditioning or cooling centers or other sort of sea walls, adaptive capacity. And it would be devastating for natural ecosystems, which can't change nearly fast enough to keep up with that amount of warming.

DOERING: Well, so, how on track are we right now for potentially a lower emission scenario that's more in line with a two degrees C warming world?

ClimateChange 2021: the Physical Science Basis - provides the most updated physical understanding of the climate system and #climatechange, combining the latest advances in climate science, and multiple lines of evidence.

— IPCC (@IPCC_CH) August 9, 2021

➡️ https://t.co/uU8bb4inBB

➡️ https://t.co/4t8uyqoLXN pic.twitter.com/bUN6fQcjWY

HAUSFATHER: So we're not on track for a below two degree warming world today. We would need to take much more action than we are right now. And that requires policy. It's not just that we're gonna have some magical technological breakthroughs that have got the whole world there without, you know, strong policy interventions by countries. But it's a lot more possible to imagine that world today, it seems a lot more likely than it did just five years ago, in part because countries are starting to make longer term commitments that are more in line with a below two degree world. In the last year, we've seen a number of countries including the US, the EU, China, Japan, South Korea, etc, commit to get their emissions to zero by the middle of the century, either 2050 or 2060. Now, you know, if the US and China and the EU and these other major emitters do succeed in getting their emissions to zero by 2050, or 2060, that is in line with keeping global temperatures well below two degrees. The challenge for us all is though, it's very easy for countries to promise to do something 30 to 40 years from now. How seriously we take those commitments really depend on how well they're reflected in near-term policies.

DOERING: Lengthy as it is, this report from Working Group I is just the first part of the sixth IPCC edition. So when can we expect the next parts of this report to come out? And what can we expect that they'll say?

Zeke Hausfather is a climate scientist and Director of Climate and Energy at the Breakthrough Institute. (Photo: Courtesy of Zeke Hausfather)

HAUSFATHER: So Working Group II, which covers the impacts of climate change on human and natural systems will be coming out early next year. And it will sort of use all of the latest science about what is likely to happen to the climate that came out in this most recent report, to look at what that means for various ecosystems, what that means for agriculture, what that means for heat waves and cities. And I think it'll, you know, paint a pretty dire picture of potential impacts, particularly in a world where we don't reduce our emissions, and give us a lot more clarity on exactly what those impacts will be. And then Working Group III is more about solutions. It'll be out next summer. And it'll explore both, you know, where the world is headed today, and what the likely pathways are that the world could take. But also, you know, what we can do to reduce our emissions, the best way we can transition the global energy system away from fossil fuels, and toward clean energy, you know, what that will cost, what the benefits of it will be. And sort of some of the equity considerations around this, you know, making sure that the countries that are responsible for the problem are the ones that are doing the most to solve it. Because one of the challenges of climate change fundamentally, is that our emissions accumulate in the atmosphere. And so what is causing climate change isn't our emissions last year, it's all of our emissions since the Industrial Revolution. And so even though countries like China and India are big emitters today, they're not responsible for the majority of what is in the atmosphere that's causing warming right now. But that also means we really need leadership and resources devoted from the rich countries to help everyone else, you know, not repeat the mistakes we made that have screwed up the climate in the process, you know, we can't slam the door behind us and tell you know, India, that sorry, our development was too damaging, so you can't develop yourselves and catch up to the luxuries that we enjoy here in the US and lift hundreds of millions of people out of poverty in the process. Right, you know, that sort of message isn't gonna work and so helping countries with technology transfer, with green financing, allowing them to, you know, minimize the amount of fossil fuels they're going to use in the future and move more quickly to clean energy without sacrificing the development needs of the people live there is going to be key. And while the rich world is responsible for half of the emissions today, and most of the historical emissions, it is going to be the poor and middle income countries that are going to be responsible for most of future emissions if we don't develop in a way that is green, and that is low carbon. And so it's really critical that we all work together on this challenge and that we create a prosperous world without destroying our planet in a way that's you know, is equal for for everyone and not just, you know, benefits the rich.

DOERING: Dr. Zeke Hausfather is a climate scientist and contributor to the most recent IPCC report. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

HAUSFATHER: Thanks. Great to be here.

Related links:

- Read the 6th Assessment Report from the IPCC

- The Breakthrough Institute | “Flattening the Curve of Future Emissions”

- About Zeke Hausfather

[MUSIC: Charles Berthoud, “Happy” on Don’t Look Back]

BELTRAN: Coming up – The green investments in the infrastructure bill recently passed by the US Senate. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth, stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Charles Berthoud, “Happy” on Don’t Look Back]

The Long and Winding Road to Green Infrastructure

According to the American Society of Civil Engineers 2021 report card, more than 7% of US bridges are considered structurally unsound. (Photo: Thomas Hawk, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran

The Senate recently passed a 1.2 trillion dollar bipartisan infrastructure bill. That’s a lot of money but roughly half of what experts say is necessary to bring US infrastructure to where it should be. As it is, the American Society of Civil Engineers gave US infrastructure a grade of C-. According to their 2021 report card more than 7% of US bridges are considered structurally unsound. 40 percent of our roads are poor or mediocre, and we waste roughly 6 billion gallons of treated water each day due to breaks and leaks. The infrastructure bill promises to address many such problems - and is now heading to the Democratically controlled House of Representatives. At the same time, Democrats are working on a 3.5 trillion dollar budget reconciliation bill. That bill would go even further with green infrastructure and aligns with the administration’s Justice40 program. That’s the goal of delivering 40 percent of the benefits of federal investments in climate and energy to disadvantaged communities. Rachel Cleetus is the policy director and lead economist in the climate and energy program at the Union of Concerned scientists. She joins me now with details from the infrastructure bill.

CLEETUS: It has some important investments in electric vehicle infrastructure. It has some important investments in public transit, and rail, in broadband in investments in climate science for NOAA, in climate resilience, and it has some important investments in making sure that we're cleaning up communities that have been subjected to a disproportionate burden of pollution. So there are some really important investments across the board in this bill. That said, they're nowhere near the scale that we need to address climate change in a just bold and equitable way. And that's why we're going to be pushing for more in another bill, the door to which was also opened earlier this month when the Senate passed budget resolution.

BELTRAN: So transportation is now the biggest single source of greenhouse gases in the United States and a key focus of the infrastructure package. How does the bill address are carbon-intensive transportation system?

Infrastructure in the United States has been deteriorating for decades. The bipartisan infrastructure bill will invest in traditional infrastructure like highways and bridges, but those who are concerned about climate change hope it is the first step in a transition to renewable energy and climate resilient infrastructure. (Photo: born1985, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CLEETUS: So the bill includes about $7.5 billion to build out a national network of electric vehicle charging stations. This is obviously a very important foundational piece to get our transportation sector to move towards a more electrified transportation sector and one where the electricity is coming from clean sources. There is some investments, about $5 billion worth of investments, in zero emission, clean buses, and 2.5 billion for ferries. But there's nowhere near enough, we need much, much more to actually move our transportation sector to a more electrified infrastructure, we need much more in the EV infrastructure, as well as in public transit. There is some public transit money, which is actually ironically, we have so far under invested in public transit in our nation, that this $39 billion worth of new investment in public transit is actually the single biggest investment that's been made. And it's still falling far short of what's needed. There is, of course, a lot of traditional investment in roads and bridges and highways. But these investments need to be more climate resilient, going forward, because we're seeing worsening climate impacts wash out roads and bridges. And that is not just a cost in infrastructure, but it can lead to business interruptions, and it has a huge economic and financial burden. So as we move forward, we have to be thinking in this holistic frame, both low carbon and climate resilient.

BELTRAN: You know, Rachel, when it comes to climate impacts and extreme weather, it's safe to say that a lot of federal response in the past has been focused on directing funds towards recovery, and adaptation instead of mitigation. In other words, lowering greenhouse gas emissions to begin with. How might these packages change that, if at all?

As climate impacts like sea level rise become more and more tangible, traditional infrastructure is becoming compromised. For instance, coastal roads like this one in Norfolk, Virginia face the recurring threat of nuisance flooding due to sea level rise. New infrastructure must integrate climate resilience features in order to last. (Photo: Aileen Devlin, Virginia Sea Grant, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CLEETUS: The bipartisan infrastructure bill that just passed, the Senate included some important investments in programs run by FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the lead agency that's responsible for our nation's response to a variety of disasters, including climate-related ones. But what we have to do now is move towards a mindset where we're acting beforehand, proactively guided by the science guided by the needs of communities, and in an equitable and just way, not just picking up the pieces after a disaster hits. And what the bipartisan infrastructure deal included was an investment in a program called BRIC that the Federal Emergency Management Agency runs, which is about investing ahead of time in communities. Now, it's nowhere near enough money, we're going to need more than that. And we hope to see that in the next bill that's prepared. But this is the way in which we have to start working as a nation. There's also a very important opportunity if in this next bill, if we can secure the Civilian Climate Corps, which is another way in which we can help make sure that communities have the resources they need to be better protected ahead of time. And then finally, all of the infrastructure we're investing in, all of these roads, bridges, electric vehicle, charging infrastructure, the power grid, all of them have to be made resilient in the face of these climate impacts. We have to be thinking about this infrastructure as long lived infrastructure that's going to be around for decades and make sure that we're using science based projections of worsening climate impacts to guide how and where we build these investments.

BELTRAN: Tribal communities have long felt the burden of climate change and pollution here in the United States. How does this bill address their needs? Or how does this bill help them in terms of climate remediation?

CLEETUS: This bill does have some investments that can help tribal communities, the two areas of investment are in electric buses to move away from polluting diesel buses, there was also investments in clean drinking water. The legislation includes a $55 billion investment in clean drinking water nationwide. And some of that is going to be targeted to a tribal nations, which are among the most disadvantaged communities in our country, and have suffered from pollution from lead pipes and other contaminants to drinking water. The investments as well in climate resilience that will flow through the Federal Emergency Management Agency, some of that will also be directed to building resilience in tribal communities that have suffered from drought from wildfires from flooding, and other climate impacts. But again, as we know, in our nation, our history of systemic racism and discrimination has resulted in tribal communities bearing a disproportionate brunt, not just of pollution, but also economic inequities. So much more is needed, and in this next bill, what we hope to see is a more holistic approach that will include investments in social justice programs, public health programs, and education and other programs that are vital for tribal communities and indigenous communities.

The infrastructure bill allocates about $75 billion of the roughly $1 trillion total to broadband, cybersecurity and electric vehicle charging station funding. (Photo: Ivan Radic, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BELTRAN: Now, just hours after passing the infrastructure package, Senate Democrats got the ball rolling on a $3.5 trillion budget resolution. From what we know so far, how would this much larger package address the climate crisis?

CLEETUS: The much larger budget resolution that has just been introduced, is taking some really important steps to address a range of issues, a few key pillars, it is going to make sure that we actually deliver on power sector targets that are ambitious. Now, we still need to see the details. This is not secured yet. But the intention here is to ensure that we can get to a power sector that's at least 80% clean by 2030. And on a path to getting 100% clean soon thereafter, that we're actually investing in electric vehicles and electric vehicle infrastructure, that we're investing in a modernized power grid that will help enable integration of higher levels of renewables. There's a very important component around clean energy tax credits, making sure that they're fully funded. These tax credits have been critical and accelerating the deployment of wind, solar and other forms of renewable energy around the country. And we want to make sure that that momentum continues going forward. They're also really important investments in climate resilience that can happen through this larger bill, including a Civilian Climate Corps, that has a model of ensuring that communities around the country are getting the resources and then technical assistance they need to prepare and be protected from climate impacts. So these are just some of the important priorities that this larger bill can help deliver on. And in all cases, it's really important that we think about this not just as a investment in technology and infrastructure, but really an investment in our communities.

As the Policy Director of the Union of Concerned Scientists’ Climate and Energy Program, Rachel Cleetus helps to design equitable climate policy and advocate for its implementation. (Photo: Union of Concerned Scientists)

BELTRAN: This bill sets up a transition from fossil fuel energy to renewable energy. How does this bill address the communities of workers who have worked in the fossil fuel energy sector for years and years?

CLEETUS: The intention is for this plan to include is a very clear set of investments in coal dependent communities and coal workers who are being disproportionately affected as we transition away from coal. These communities, these workers deserve to be treated fairly. They have helped keep the lights on in our country for generations. And now, we need to make sure that they are not left behind as we make this transition. That means ensuring that there is investments and diversifying these local economies in treating workers fairly in terms of providing benefits, providing lost wage replacement for a period of time, providing job training, and educational benefits so that they can also avail of new economic opportunities going forward.

BELTRAN: Rachel Cletus is the policy director with the Climate and Energy Program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today, Rachel.

CLEETUS: Thank you so much for having me.

Related links:

- Learn more about Rachel Cleetus and the Union of Concerned Scientists

- NYTimes | What’s in the $1 trillion infrastructure package?

- NYTimes | Senate Passes $1 Trillion Infrastructure Bill, Handing Biden a Bipartisan Win

- Washington Post | Biden aims for sweeping climate action as infrastructure, budget bills advance

[MUSIC: Shakey Graves, “Tomorrow” single, Dualtone Music Group]

Drought Threatens Migratory Birds

Sump 1A in the Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge after being drained. (Photo: Erik Neumann/JPR)

DOERING: Every year, over a million birds migrate to several National Wildlife Refuges along the Oregon-California border. But this year unprecedented drought and low water levels pose a serious threat to the survival of several migratory bird species. Erik Neumann from Jefferson Public Radio has the story.

(Sound up of walking through grass)

NEUMANN: John Alexander is walking along wooden planks on the marshy edge of Upper Klamath National Wildlife Refuge. Between the bullrushes and willows, a 10-foot-high black mesh net is set up to catch songbirds that are singing all around us.

ALEXANDER: Western Tanager, kind of in the back. Sweet, sweet, sweet, I’m so sweet. Yellow warbler, long distance migrant. Beautiful brilliant yellow bird.

NEUMANN: Alexander is the director of the Klamath Bird Observatory. He’s here with a group of research biologists surveying birds at their Upper Klamath Lake field station.

Klamath Bird Observatory Director John Alexander removes a bird from a mist net for their field station survey near Rocky Point on Upper Klamath National Wildlife Refuge. (Photo: Erik Neumann/JPR)

ALEXANDER: So, we write their band number down, and then they take information about the bird’s body condition, its size, how much fat is on it.

NEUMANN: They’ve been collecting data here since 1997. Alexander says water levels are noticeably low this year.

ALEXANDER: See where those sticks are laid up? That’s the normal water level this time of year.

NEUMANN: So where we’re standing right now, can you kind of describe what it would be like in the past?

ALEXANDER: I’d be waist deep in water, with chest waders on.

NEUMANN: Upper Klamath Wildlife Refuge is one of six refuges in the Klamath Basin. These marshes provide temporary habitat for countless songbirds and waterfowl that migrate as far as Mexico and Alaska.

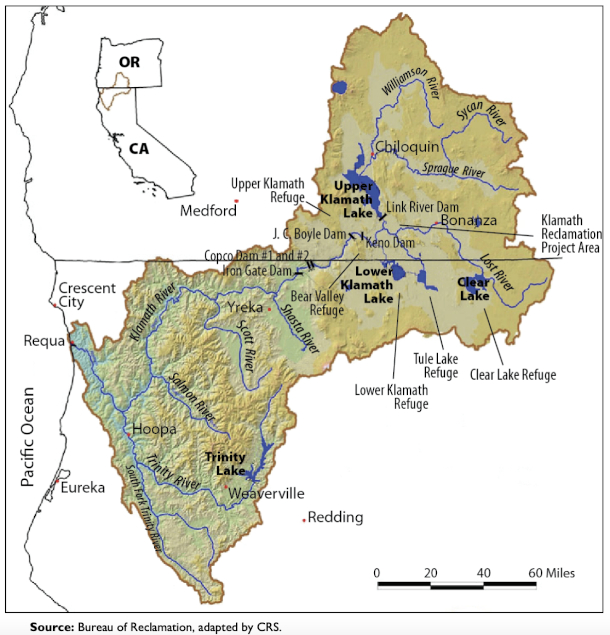

Map of the national wildlife refuge complex in the Klamath Basin. Klamath Marsh Refuge not shown on map. (Image: U.S. Bureau of Reclamation)

NEUMANN: Amelia Raquel is a biologist with the sportsmen conservation group Ducks Unlimited.

RAQUEL: The basin as a whole in southern Oregon northeastern California in my opinion, and I think would be supported, is the lynchpin for migration habitat in the Pacific Flyway.

NEUMANN: But when the refuges are dry, that habitat is gone. In this highly managed basin, the refuges have been given the lowest priority for water, after local tribes and endangered fish, and farmers. That can have devastating consequences. Last year tens of thousands of birds died from avian botulism. The natural waterborne bacteria thrive in warm temperatures when water is low. This year’s drought is worse. So it’s prompting some creative solutions.

On a nearby dike that divides two wetlands in Tule Lake Wildlife Refuge, shallow water is being pumped from one side to the other. Raquel, with Ducks Unlimited, is working on the project with local farmers like Scott Seus.

SEUS: We’re taking what precious water is here and trying to accumulate it all into one spot to save 60-70,000 birds that perished last year that could be proportionately more than that this year.

Amelia Raquel with Ducks Unlimited and Klamath Basin farmer Scott Seus stand in front of a pump moving water from Sump 1A to Sump 1B on the Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge. (Photo: Erik Neumann/JPR)

NEUMANN: The hope is that by collecting the shallow water in one area, they’ll ward off another major botulism outbreak. Refuge managers from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declined an interview request for this story. While there’s more attention on the drought in the Klamath Basin this year, in reality, it’s not the only reason the refuges don’t have water.

COLE: I don't go to the refuge's too often anymore because there's not a lot to see. It doesn't change much. It's pretty dry.

NEUMANN: That’s Ron Cole. He worked at the refuges for the Fish and Wildlife Service for 26 years, much of it as a manager. Cole says the local water rights and the endangered species act, which protects several species of nearby fish, have deprived the refuges of the water they need to create functioning wetlands, even during normal water years.

COLE: Thank God, we have the Endangered Species Act to help save these species. But we have to implement it in such a way that we don't create more of the same elsewhere.

NEUMANN: The refuges also do have some water rights, on par with those of farmers. One for Lower Klamath Wildlife Refuge dates back to 1905. But, Cole says, the federal agencies, the Bureau of Reclamation and Fish and Wildlife Service, could never agree on how to get that water to the refuge.

He says, when the refuges can get water, managers are good at creating habitat for birds and recreation for people.

COLE: We do know how to do those things and it worked and it wasn't broke, but we broke it. We broke it. And that's the saddest part of all of it is we broke that refuge and I'd like to see us put some effort into fixing it.

NEUMANN: Going forward, he says, whether in drought years or not, all the different groups in the basin need to find ways to work together with the limited water that exists if anything is going to change.

I’m Erik Neumann, reporting.

DOERING: Erik Neumann’s story comes to us courtesy of Jefferson Public Radio.

Related link:

JPR | Out of the Spotlight, Thousands of Birds Face a Dry Year at Klamath Basin Refuges

[MUSIC: Shakey Graves, “Roll The Bones” on Roll The Bones X, Dualtone Music Group]

BELTRAN: Coming up after the break – looking to Henry David Thoreau for guidance on getting through today’s challenges. But first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Note on Emerging Science: The Beetle That Can Survive Being Eaten

A study by Shinji Sugiura, a researcher at Kobe University, observed that an aquatic beetle that inhabits paddy fields can pass through a frog's system undigested. (Photo: Chris Luczkow, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

LYMAN: Most insects are doomed when they get eaten by a frog. But scientists recently discovered that a species of water beetle, Regimbartia attenuate, can actively travel through a frog’s digestive tract, survive stomach acids and lack of oxygen, and pop out of the frog’s rear end unscathed. Although rare, some animals do survive after being ingested by another animal. Some snails, for example, can seal their shells shut after being eaten by a fish or a bird, and wait to be excreted from the predator’s digestive tract. But the case of the water beetle is the first documentation of prey actively escaping through the digestive tract of a predator. Shinji Sugiura, an ecologist at Kobe University in Japan, put the water beetles in cages with frogs in his laboratory. The frogs readily ate the beetles, but Sugiura was quite surprised to see the beetles exit from the frogs’ behinds and continue on their way apparently unharmed. Sugiura conducted some 30 beetle-frog tests, and found that over 90 percent of the beetles survived being eaten. The average time it took for the beetles to escape was about six hours, but one beetle made it through a frog’s digestive tract in only six minutes. Sugiura immobilized some of the beetles using wax to stick their legs together to determine that the insects were actively escaping from the frogs’ digestive tracts. None of the immobilized beetles survived, and their remains took a day or more to pass through the frogs’ bodies.

Sugiura plans to test the beetles’ survival abilities by pairing the insects with bigger frogs, toads and fish. That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

Related link:

Kobe University | “An Insect Species Can Actively Escape From The Vents Of Predators Via The Digestive System”

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Clifford Brown, Max Roach Quintet, “Sandu” on Study In Brown, UMG Recordings]

Beyond the Headlines

The Spratly Islands and reefs in the South China Sea, as seen from space. (Photo: Image Science and Analysis Laboratory, NASA-Johnson Space Center, Public Domain)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

It's that time of the broadcast when we take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. And he joins us now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Paloma. We're going to take a look at a geopolitical and military standoff in the South China Sea, it's made some of its own headlines, but it also has some environmental buzzkill attached to it.

BELTRAN: So what's the environmental issue here?

DYKSTRA: In the South China Sea, the People's Republic of China is looking to build a military base and claim some property in the form of artificial islands. They've directed their fishing fleets to move in around the islands. And they're building a runway and a military base in the middle of what had been relatively pristine waters.

BELTRAN: And what effect is that having?

DYKSTRA: Well, number one, there are hundreds of boats going in and out of there: China's fishing fleets, fishing fleets from the nations who object to this, like Vietnam and the Philippines and Malaysia; occasionally, American naval boats keeping a watchful eye on this situation. But primarily, the construction ships and the Chinese naval ships that are pretty much stationary around these islands have caused damage to coral reefs, largely by helping to create algal blooms, and those in turn, are largely created by sewage that's dumped by these ships, harming the waterways that China wants to claim as its own land.

BELTRAN: Well, let's hope something can be done. It would be a shame to lose this marine habitat. What else do you have for us this week, Peter?

Headstones in Brewer Hill Cemetery, which is home to the remains of more than 7,000 slaves, freed African Americans, and Black veterans. (Photo: Ken Mayer, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: In Annapolis, the capital city of Maryland, there's some Black history that could be washed away with a link to climate change. The Brewer Hill Cemetery is the oldest African American graveyard in Annapolis. It contains remains of more than 7000 people, some slaves, freed slaves, historic figures in the African American community, and veterans from the Civil War, the Spanish American War, World Wars One and Two, and even the Korean War. There's a real problem, because the torrential rains that have become more frequent due to climate change, are literally washing the graveyard away.

BELTRAN: And as you mentioned, Peter, this is a historic site. So I imagine people want to protect it. Is there anything being done?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, part of it is just changing the building codes and regulations for the structures around the cemetery. The other part of it is simply climate and the big picture change. To limit the damage of any kind from climate change is something that would help save this historic cemetery.

BELTRAN: Peter, what do you have for us from history books this week? I understand you have a personal connection to this one.

DYKSTRA: I do. It's the 60th birthday this month of the Cape Cod National Seashore. Senator John F. Kennedy was the big proponent in getting the first National Seashore designation. And lo and behold, by 1961, Senator Kennedy was President Kennedy. He got to sign his pet project into law, protecting a huge amount of the outer Cape, the part that faces the ocean.

Sunset at Cape Cod National Seashore, which President John F. Kennedy designated on August 7, 1961. (Photo: Daniele Bertin, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BELTRAN: Yeah, it's a beautiful place. But unfortunately, it's one of the multiple sites in the East Coast that are threatened by sea level rise.

DYKSTRA: That's right. You gotta remember Cape Cod is nothing more than a sandbar created by the end of the Ice Age thousands of years ago. It's important to me because I spent at least a couple weeks of every year of my life, for years, at my uncle's place about a half mile from the National Seashore. And I got to see nature firsthand in this relatively pristine protected area. A happy 60th birthday to the Cape Cod National Seashore.

BELTRAN: Well, thank you, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org. And dailyclimate.org. Thanks a lot. Talk to you again soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Paloma. Thanks a lot and we'll talk to you soon.

BELTRAN: And there's more on these stories at the Living on Earth website. That's loe dot org.

Related links:

- Mongabay | “Geopolitical Standoff In South China Sea Leads To Environmental Fallout”

- E&E News | “Floods Are Washing Away Black History In This Md. City”

- Cape Cod National Seashore

[MUSIC: Snarky Puppy, “Shofukan” on We Like It Here, GroundUp Music]

Sheltering with Thoreau in the Age of Crisis

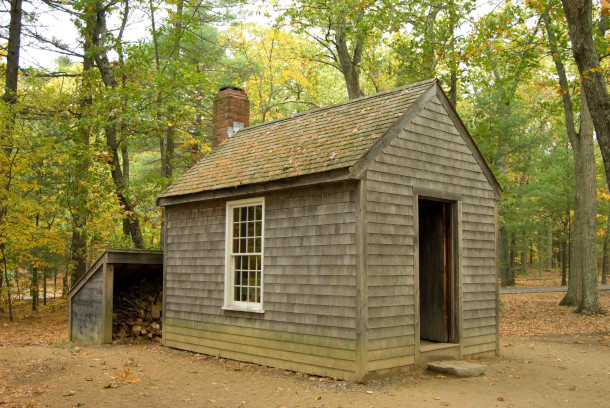

At Walden Pond, Thoreau developed his voice as a writer and generated much of the journal material that would later become the nature writing classic Walden. (Photo: Ashok Boghani on Flickr)

DOERING: The COVID-19 pandemic brought the world to its knees and slowed the pace of life for many of us. For writer David Gessner, this era of retreating to our homes brought to mind one famous expert in social distancing, Henry David Thoreau. In his book, “Quiet Desperation, Savage Delight: Sheltering with Thoreau in the Age of Crisis,” David looks to Henry David as a guide to living through a pandemic, a time of racial reckoning, and a climate crisis. David, welcome back to Living on Earth!

GESSNER: Thanks. It's great to be here again.

DOERING: Well, could you please introduce us to Henry David Thoreau for listeners who might not be familiar with his work?

GESSNER: Yeah, the big moment in Thoreau's life was in 1845. On July 4, his personal Independence Day, when he went to the woods, in Concord, Massachusetts, near where he lived not far from home, and squatted on Ralph Waldo Emerson's land. He kept journals, he explored the natural world, and he developed his voice as a writer there. That voice would find full flower in the book Walden, which many of us were forced to read in high school; some of us were bored by it, others had our lives changed by it.

DOERING: You mentioned being forced to read Walden in high school. You also in the beginning of your book, you write about how Henry David Thoreau ruined your life.

GESSNER: Yeah.

DOERING: Could you set that up? And could you read that passage for us?

“Quiet Desperation, Savage Delight: Sheltering with Thoreau in the Age of Crisis” reexamines Thoreau during the pandemic. (Image: Courtesy of David Gessner)

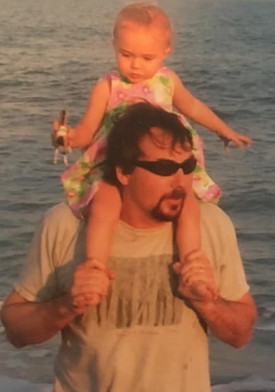

GESSNER: I would be happy to. The very beginning of the book, it starts like this: [READING] 16 years ago, when our daughter was just a baby, my wife and I took her on a trip to Walden Pond. As we approached the place where Henry David Thoreau's cabin once stood, with my daughter riding up on my shoulders, I said to her, "That's where the man lived, who ruined your father's life." Ruined in a mostly good way I meant. I discovered Walden when I was 16 and never quite recovered. I began to question the values of the system I found myself in. "The life that men praise and call successful is but one kind," Thoreau wrote, and I hollered, amen. In this way, Thoreau was like a more profound, less musical version of getting stoned and listening to Pink Floyd. But the effect was more lasting. I began to keep a journal in high school, and I keep one to this day. After college, the sentences from Thoreau's book, were still rippling outward through my life, affecting the choices I made. To hell with law school or any normal career, I would become a writer, I would value solitude. And I would move to my very own Walden.

DOERING: Can you tell me more about that idea that you had during this pandemic, this unprecedented time, David, why revisit Thoreau during the pandemic?

GESSNER: It was a weird string of coincidences really, for me. I had rebuilt the writing shack in my backyard on a tidal marsh in North Carolina that I built on my 50th birthday, but had been destroyed. In hurricane Florence, it flooded and basically floated out to sea. And I was rebuilding it that January before the pandemic. And I also, I was reading a biography of Thoreau by Laura Walls, great new biography. And I was thinking about self reliance and pulling back and being less busy. And then the pandemic hit. And I had this shack to retreat to. And I really took it as an opportunity to slow down. And I've always been interested in my own backyard, which is a salt marsh, which connects me to the Atlantic and the greater world. But I really studied it and I started to study the clapper rails, these birds in my backyard, and fiddler crabs. And it was so strange that this time of supposed isolation was a time movement and migration in the animal world. And you were seeing these flocks of birds come over. So like a lot of people, I rediscovered my own backyard and Thoreau if nothing else, is kind of the patron saint of discovering one's own backyard.

DOERING: So of course, I know that you're not new to observing nature, David, but I'd love to hear more about how sheltering in place really shaped your habits in the salt marsh that you call home.

Gessner’s daughter rides on his shoulders at Walden Pond, a moment Gessner recounts in the opening of his book. (Image courtesy of David Gessner)

GESSNER: Yeah, I think that the biggest thing for me was realizing that it wasn't just a casual thing. It was a discipline. Thoreau famously said, if you take a walk in the woods, and you have village thoughts, if you're thinking about your Things To Do List, your you know what you've got to do tomorrow, and not having Woods thoughts. You're not really walking in the woods. And I started to, you know, there were many great blue herons out on the marsh and I would watch them and I would see their patience, which isn't like kind of a groovy easy patience. It's waiting, waiting, waiting and then hitting, because it's effective, because it works. So I really, you know, I paid lip service to this stuff over the years, and I've talked about how, you know, we should try to be less anthropocentric and beyond ourselves. But what I was starting to see is, it's a discipline.

DOERING: So learning one's own backyard, part of your project here, it's not all birds and butterflies and wonderful things. In your case. It actually involved understanding this terrible legacy of racist terrorism in your hometown of Wilmington, North Carolina. What happened and what kind of reckoning is happening or still needs to happen?

GESSNER: Well, in 1898, before what was soon known as America's only coup, Wilmington was a majority black town. And it was a kind of cosmopolitan town because it's a port town. And it was actually a place where African Americans held political office held jobs on the police force. And where African Americans from elsewhere would come to Wilmington as kind of a refuge, a place to feel safe. Well, that all ended in November of 1898, when the minority white ruling class fired up the white lower class, essentially, and had a violent overthrow of the government. That legacy continues to this day in Wilmington, where it's because not only did they kill up between 80 and I think 400 people, they also exiled many others. So suddenly, this this place that had been a refuge became a nightmare, basically, and that legacy has continued to this day. Gradually, the history is being acknowledged, you know, our George Floyd protest, had another layer to them guess, as many towns do. But here we were in the south. So adding that to the just intense mix of kind of polar opposites of the year where we have the solitude, this isolation, and suddenly we're just so connected, not just to the place, but to history.

DOERING: So you mentioned in your book that Henry David Thoreau doesn't simply isolate himself from the world, he engages with it, how do you feel that he can help us meet the challenges of our current times?

Thoreau spent his time at Walden Pond in a 10x15 feet hand-built cabin, writing journals, reading, and observing nature. The above is a replica. (Photo: Ryan Taylor on Flickr)

GESSNER: So you know, Thoreau wasn't a hermit. He was famously a part of his neighborhood. In a way, Walden is just a response to people yelling down to him from the road, what the hell are you doing down there? He says, here's what I'm doing. And Laura Walls said, Thoreau didn't go to Walden to escape the world, but to confront it. You know, Civil Disobedience, which is not the full title, but it's how we know his famous essay, outlines his night in jail when he refused to pay tax that would support the Mexican War, but also slavery and the extension of slavery. And it was just one night in jail. It wasn't a great hardship. But symbolically, it had huge impact on thinkers from Martin Luther King to Gandhi. And it was because he said, that one could nonviolently resist what one deemed wrong. And he stuck to that throughout. So we think of him as the hermit at Walden. And he did go to Walden on July 4, but on a July 4, nine years after he went to Walden, he was in Framingham, Massachusetts with an upside down hanging American flag and another speaker who was burning the constitution and he was railing against slavery and in a classic Thoreauvian fashion, he kind of poo pooed the strict abolitionists because they were part of a group. But he individually, vehemently opposed slavery and was one of the only public supporters of John Brown after the rebellion that was a prelude to the Civil War basically.

DOERING: David, there's a passage in your book that explores how Henry David Thoreau provides some insight for this time of racial reckoning that we're in now. Could you read that passage?

GESSNER: Sure. [READING] What are we willing to give up to try and affect the change we want? Are we willing to sacrifice our private pleasure for the public good? Are we willing to interrupt our oh, so precious lives? It is dangerous business leaving the woods behind. It is scary out in the streets. Of course, it is more complicated than that, in at least one case, the ideas that inspire those on the streets, were born in the woods. I'll let Martin Luther King have the last word. He writes, "I became convinced that noncooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good. No other person has been more eloquent and passionate in getting this idea across than Henry David Thoreau. As a result of his writings and personal witness, we are the heirs of a legacy of creative protest. The teachings of Thoreau came alive in our civil rights movement. Indeed, they're more alive than ever before. Whether expressed in a sit in, at lunch counters, a Freedom Ride into Mississippi, a peaceful protest in Albany, Georgia, a bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. These are outgrowths of Thoreau's insistence that evil must be resisted, and that no moral man can patiently adjust to injustice."

While sheltering, Gessner further acquainted himself with the clapper rails in his salt marsh backyard. (Photo: Tom Murray on Flickr)

DOERING: It's remarkable how much of an impact Henry David Thoreau had on Martin Luther King and the way he was thinking about nonviolence and standing up against injustice.

GESSNER: Yeah. And you know, one interesting thing is people put Thoreau down and say, well, that was just one night in jail and it's just symbolic. Well symbols matter. And Thoreau in a way was famous for taking small things. Like he saw some red ants doing battle with black ants and he talked about a great war that was occurring. So in a way, that was a real part of what Thoreau did, and he saw the large and the small.

DOERING: One of the things that you discuss in your book is the impermanence of things that we call home, you know, grieving changes on the local scale, like the death of your writing shack, but also on a global scale with climate change. What insights does Thoreau have to offer on this, do you think?

GESSNER: Well, I just read a passage, it's not in the book, about how when a friend dies, you know, we die too, and how gradually, it starts to kind of pull away our core. And in the middle of the summer, a very close friend of mine, Brad Watson, who's a Great Southern writer, who I know, he was a National Book Award finalist, but he never really got his due, I felt, died suddenly of a heart attack. And for me, Thoreau lost his brother early on. And, you know, it always felt like he was looking for that one close friend who he could be completely honest to and trust in. And for me, that was a first loss of a peer. And that, and the events of the world that you're describing, and the climate, you know, I mentioned all the fires and the hurricanes, it can wear a spirit down. And I guess, on a large scale, I would say, Thoreau's looking to a world beyond the human world is vital, but on a smaller scale, recognizing the vital importance of the political, but at the same time, having carved out your private existence. You know, I actually have a chapter in there, not about Thoreau, but Montaigne, who said famously, the French writer from the 16th century, first essayist, he famously said, “we almost have a back shop to call our own”. So in a way, the pandemic year is perfect for that. It's so political, for obvious reasons. We had an election going on, I would come back from listening to bird calls, to listen to CNN, in my house, right and it was such a fraught year, but to keep you know, and to fight the political fights, and that's important, but to also keep that back shop, that place separate from there, where you're not overrun with the noise and clamor, and you have your own space, whether that's a shack, a walk you go on, a room in your house, a place, a garden in the neighborhood, just someplace apart, where you can refuel and renew yourself.

DOERING: David Gessner is the author of Quiet Desperation, Savage Delight: Sheltering with Thoreau in the Age of Crisis, and teaches at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. Thank you so much, David.

GESSNER: Thank you. I always love talking to you guys. And this was great.

Related links:

- Visit David Gessner’s author website

- Find the book “Quiet Desperation, Savage Delight: Sheltering with Thoreau in the Age of Crisis” (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Glymnopedie No. 1” on Kaleidoscope, High Note Records]

DOERING: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Anna Canny, Jay Feinstein, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Joshua Siracusa, Tivara Tanudiaia and Jolanda Omari.

BELTRAN: Sadly, on August 16th long time colleague and friend Thurston Briscoe died from cancer. Thurston helped market, promote and edit Living on Earth after a long career at NPR and WBGO. In the weeks ahead we will have a fuller remembrance, but he is already missed.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth.

BELTRAN: We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Paloma Beltran.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth