‘Mosquito-Borne’ No More?

Air Date: Week of August 27, 2021

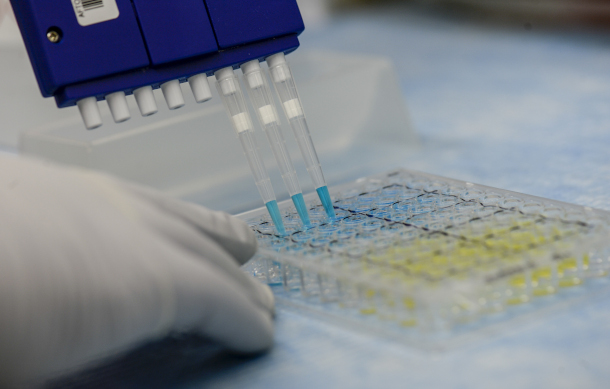

Dengue virus is spread through the bite of an infected mosquito. According to the CDC, 40% of the world’s population live in areas with a risk of dengue. (Photo: Sanofi Pasteur, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Mosquitoes carry diseases like malaria, Zika, and dengue fever that kill more than a million people every year. In a breakthrough study, scientists released mosquitoes infected with a special kind of bacteria into an Indonesian city and saw a 70% drop in dengue cases. World Mosquito Program Founder Scott O’Neill joins Host Jenni Doering to talk about how the Wolbachia bacteria can reduce transmission of dengue virus and save lives.

Transcript

[MOSQUITO BUZZ SFX]

DOERING: They’re not just annoying. Mosquitoes are the most efficient disease transmitters on the planet, killing more than 1 million people every year according to the World Health Organization. But a tiny and unlikely hero could help in the fight against diseases like zika virus and yellow fever. It’s a type of bacteria called Wolbachia, and it makes mosquitoes much less likely to carry and transmit disease. Scientists at the World Mosquito Program recently reached a breakthrough in a trial that used Wolbachia to try to combat the virus that causes dengue fever. They released mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia into parts of an Indonesian city and saw a huge drop in dengue cases in those neighborhoods. Scott O’Neill is the founder of the World Mosquito Program and joins me now from France. Welcome to Living on Earth!

O'NEILL: Hi, it's a pleasure to be here with you.

DOERING: So tell me about how you and your colleagues developed this technique of using the Wolbachia bacteria to combat dengue fever.

O'NEILL: Yeah, so I was very interested in the properties of Wolbachia, which enabled it to be able to spread into a wild mosquito population and maintain itself. And we spent a lot of time working out how to transfer Wolbachia into mosquitoes. So it was stably maintained. When we got it into the mosquitoes, we found out by chance that it actually prevented a range of viruses from growing, replicating in the body of the mosquito, and they can't grow in the body of the mosquito, they can't be transmitted to people: dengue fever, Zika, chikungunya, yellow fever, all these viruses transmitted by the same mosquito couldn't grow.

DOERING: How does this Wolbachia bacteria actually push out the viruses?

O'NEILL: Yeah, so what it does is it stops them from replicating. And we think it's doing that in a couple of different ways. Most importantly, it's competing for key resources that the virus needs to be able to produce more copies of itself. And as a result, the virus doesn't grow as well, if this Wolbachia is in the insect, and if it doesn't grow, then it can't get spat out again when it bites somebody in its saliva, which is how people get the virus transmitted to them. So it's a natural way in which we can completely stop transmission of a whole range of viruses simultaneously.

DOERING: Right. So this is a really common bacterium in nature, but it wasn't already in mosquitoes.

O'NEILL: That's right. So it occurs naturally, we estimated around 50% of all insects and bees, or butterflies, all sorts and including a number of mosquitoes. But it didn't occur in this one mosquito that transmits all these viruses to people. And so the work of my laboratory for many years was involved in transferring it into that mosquito so that it would maintain itself there, which we were ultimately successful at doing.

DOERING: How did you tweak it over the years?

O'NEILL: Oh, you know, it's, it's a long and complicated story that took us many years of different approaches of, you know, at the end, we needed to inject it into mosquito eggs that have been laid and handled in a certain way with certain needles with preparations of or Wolbachia extracted from a fruit fly. And took us many, many years. But once we had done at once, we were able to have a colony of mosquitoes and with the discovery that it would prevent the transmission of these viruses. We then embarked on a program where we wanted to release mosquitoes that contain this fall back here into the wild, where they would then breed with wild mosquitoes and pass the Wolbachia into that population of wild mosquitoes and it would spread naturally and maintain itself.

According to the studies by researchers at the World Mosquito Program, infecting mosquitoes with the Wolbachia bacteria can reduce the incidence of dengue, Zika, chikungunya and yellow fever. (Photo: Master Sgt. Brian Ferguson, U.S. Air Force Photo, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: So I understand you've tested this first in Australia, and then Yogyakarta, on the Indonesian island of Java, where dengue is very common. So how did you go about testing this in Indonesia?

O'NEILL: Yeah, so we collaborated with a local university in Indonesia, but also with scientists in other parts of the world, including UC Berkeley, for statistical assistance with the trial. And we took the city of around 400,000 people and we cut it up into 24 areas. Of those 24 areas, 12, or half of them got the Wolbachia release of mosquitoes and the other half didn't. After we let the Wolbachia into the mosquito population, and it had established, we then turned on surveillance for disease in healthcare clinics throughout the city. And we were looking to see the people that came to health care clinics if they were tested and found to be positive for dengue. Did they live in a Wolbachia area? Or did they live in an area that didn't receive Wolbachia? And what we found is that there was a 77% reduction in the number of dengue cases in people that lived in Wolbachia areas, and an 86% reduction in hospitalizations if you lived in a Wolbachia area. We're very delighted about that. But it's good to understand that in this sort of trial design, they're probably an underestimate. And the reason is that, you know, even though you might live in a Wolbachia area, you might not spend your whole time there, you might get on your motorbike and go across into a neighboring area to go take your child to school or to go to the market and you could catch dengue there. So we think that the true impact we're having on things is bigger than the 77%, we measured. And we've now covered the whole city, we've filled in the control areas so that all the people within Yogyakarta got to benefit from it, from the intervention. And now we're waiting to see with the large coverage, whether we actually eliminate dengue transmission completely from Yogyakarta in upcoming years.

DOERING: So how did you actually gain the community's trust? I mean, you were proposing to release live mosquitoes right next to their homes with this bacterium that maybe you know most people don't haven't have never heard of don't know much about.

O'NEILL: We spent a lot of time doing engagement with communities, talking to communities about what we're doing, listening to their concerns and answering those concerns. And when we work in an authentic way with communities, we find that communities are very supportive. And I think part of the fundamental reason for that is that people are fearful of dengue and fearful of their children getting sick and potentially dying of dengue, and not really having any effective treatments at the moment. And so given that risk, people seem to be quite willing to try out something novel.

DOERING: Right, I understand Dengue fever is a pretty serious disease. What is it like when someone comes down with this?

O'NEILL: It can be terrible for people. If it doesn't kill you, which it does to many people, you know, it's a spectrum of disease, sort of, like we're seeing with COVID. You know, some people die, and some people have mild disease, it's the same with dengue. If you have a bad dose of it, you know, you have these piercing headaches, have a metallic taste in your mouth, a rash on your body, you're vomiting, you can't get out of bed to go to the toilet. People will describe it as one of the worst couple of weeks of their lives. So it's quite devastating for communities, hospitals fill up people can't go to work. It has a big social and economic costs as well as a direct health cost.

In 2016 Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes were released over a six-month period throughout parts of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. After several years of trials rates of dengue were 77% lower in the research areas compared to areas that did not receive mosquitoes. (Photo: Master Sgt. Brian Ferguson, U.S. Air Force Photo, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: So how likely do you think it is that Wolbachia could someday help completely eliminate dengue?

O'NEILL: Well, I think we're probably going to need multiple tools. You know, it's such an entrenched problem, up to 400 million people being infected every year, all the top major tropical cities of the world at risk of dengue. Probably any one tool by itself may not be sufficient to completely eliminate, but a combination of tools and a concerted effort to work on dengue elimination, I think we should be able to make great headway in the future to reducing disease. Certainly, where we're releasing more back here and putting it out, we're seeing elimination of local disease, we'd love to see the methods scaled up enormously around the world to benefit communities. And so we're hopeful that in the coming years, we'll see an expansion but just because of the size of the problem, it's going to take many years.

DOERING: Scott O'Neill is the founder of the World Mosquito Program. Thank you so much, Scott.

O'NEILL: Yeah, you're very welcome. Thanks for having me on.

Links

The Atlantic | “A Pivotal Mosquito Experiment Could Not Have Gone Better”

Nature | “The Mosquito Strategy that Could Eliminate Dengue”

Learn more about the Wolbachia-mosquito studies carried out by the World Mosquito Program

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth