August 27, 2021

Air Date: August 27, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

A Block on Oil Drilling in Alaska

View the page for this story

A major Alaska drilling project to tap 600-million-barrels of oil has been blocked. A federal judge ruled in favor of Indigenous and environmental groups, finding that the permitting process has yet to fully consider impacts on the climate and polar bears. Both the Trump and Biden Administrations have backed this ConocoPhillips project, and to explain why, Host Jenni Doering speaks with Pat Parenteau of Vermont Law School. (10:15)

Climate and the California Recall

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

The upcoming recall election for California Governor Gavin Newsom, who is aggressively pursuing climate action, could result in a climate change-denying candidate becoming Governor. Co-hosts Jenni Doering and Aynsley O’Neill talk about how the unusual rules for California recall elections could impact climate policy in the state and beyond. (02:41)

Note on Emerging Science: Oh, What a Tangled Web They Weave

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

New research suggests that some sticky spider webs contain paralytic neurotoxins that help catch prey. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman reports. (01:34)

‘Mosquito-Borne’ No More?

View the page for this story

Mosquitoes carry diseases like malaria, Zika, and dengue fever that kill more than a million people every year. In a breakthrough study, scientists released mosquitoes infected with a special kind of bacteria into an Indonesian city and saw a 70% drop in dengue cases. World Mosquito Program Founder Scott O’Neill joins Host Jenni Doering to talk about how the Wolbachia bacteria can reduce transmission of dengue virus and save lives. (07:48)

Chemicals and Breast Cancer Risk

View the page for this story

Higher levels of the hormones estrogen and progesterone lead to a greater risk of breast cancer. Researchers at the Silent Spring Institute have shed new light on how chemical exposure can raise those hormone levels in women. They found that nearly 300 chemicals increased one or both hormones. Environmental Health News reporter Elizabeth Gribkoff talks with Host Aynsley O’Neill about this latest research. (06:23)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

July 2021 was the Earth’s hottest month on record, and in this week’s Beyond the Headlines segment Peter Dykstra of Environmental Health News sat down with Host Aynsley O’Neill to explain the climate change connection. They also discuss exciting developments in emissions reduction for steel making and the anniversary of the discovery of destructive boll weevils in Alabama, which ironically helped one enterprising town find economic prosperity. (04:28)

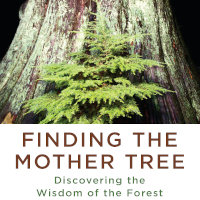

Finding the Mother Tree

View the page for this story

An intricate web of roots and fungi connects life in an old growth forest, allowing ancient “Mother trees” to nourish and protect their kin. Forest ecologist Suzanne Simard studies these connections at the University of British Columbia and takes readers into the field with her in her new book, Finding the Mother Tree. She joins Host Jenni Doering to share her research findings and reflects on how mother trees helped her through the challenges of motherhood and a cancer diagnosis. (13:49)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Elizabeth Gribkoff, Scott O’Neill, Pat Parenteau, Suzanne Simard

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill

Scientists have discovered a bacteria that can reduce the transmission of mosquito borne illnesses.

O'NEILL: We found out by chance that it actually prevented a range of viruses from growing, replicating in the body of the mosquito, and they can't be transmitted to people: dengue fever, Zika, chikungunya, yellow fever, all these viruses transmitted by the same mosquito couldn't grow.

DOERING: Also, research finds that old growth, or mother trees, pass on energy and information to their offspring.

SIMARD: You know, an old tree never really dies, right? Yeah, I mean, the individual passes on, but that dispersal of energy to the next generations or even to the soil food web -- it's alive. Right, it's alive with the past, it's alive with the present and it's alive with the future.

O’NEILL: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

A Block on Oil Drilling in Alaska

A ConocoPhillips oil refinery in California in 2008. At its peak, this refinery can produce over 100,000 barrels of oil every day. (Photo: Thomas Hawk, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

O’NEILL: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

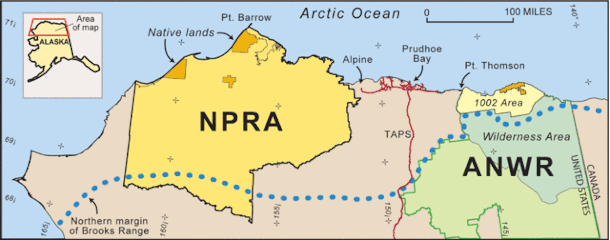

A major Alaska drilling project that would tap into 600-million-barrels of oil has been put on hold by a federal judge. The Willow project in the National Petroleum Reserve would produce as much as 160,000 barrels a day for ConocoPhillips and had the support of both the Trump and Biden Administrations. Judge Sharon Gleason of the U.S. District Court ruled in favor of Indigenous and environmental groups, finding that the permitting process failed to fully consider the impacts on the climate and polar bears. For more I’m joined by Pat Parenteau, professor of environmental law at Vermont Law School. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Pat!

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Jenni, good to be with you.

DOERING: Yeah, so how big of a setback is this decision for the Willow project?

PARENTEAU: Well, these are procedural rulings, right? I mean, the judges didn't say 'you can't drill', she really doesn't have the power to do that. But you know, they're the kinds of rulings that will take a long time for the Department of Interior to fix. You can imagine this challenge of having to actually quantify how much additional carbon is going to result from this leasing of this area in Alaska. It's a really complicated thing, it's going to take some time to do that. The consideration of alternatives isn't going to, I don't think consume a lot of time, but it will take some time. When you go back to correct errors in these environmental impact statements, you have to go back through the same process that you did when you adopted the EIS, which means an opportunity for public comment. And you know, this area we're talking about is the homeland of the Inupiat people, several tribes with certain claims that have to be respected. And the Biden administration, of course, has made a big point with environmental justice. So that's going to take some time. And then finally, the Endangered Species Act, that's got to go back through another round of what's called consultation. And what the court said is, if you're going to say that impacts on the polar bear and its habitat, this is areas where the polar bear dens, so if you're going to have impacts, and you say you're going to mitigate them, you have to demonstrate not only how you're going to mitigate them, but what requires the mitigation. How will the mitigation actually be enforced? And if it doesn't work the way you thought, how are you going to correct for that? So my estimation is, if this decision is not overturned by the Ninth Circuit, it's going to take more than a year to go back through all of this review and assessment and outreach before they could move forward again.

Map of northern Alaska showing location of the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska, where the Willow Project would be developed, and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. (Photo:USGS)

DOERING: Wow, and so to what extent is this just a matter of documenting the possible impacts of this project and then moving forward with the same plans? Or do you think they might actually have to change the project scope a little bit here?

PARENTEAU: I think they might have to change certainly the footprint on the ground. I think the judge's ruling is basically saying you didn't work very hard to limit the environmental impacts from this drilling activity. So I'm not sure that it would shrink the amount of area that has been leased. But it's certainly going to have an impact on how the project is configured. And of course, it does give the Biden administration the opportunity to take a second look at this, and maybe decide that this amount of leasing or this amount of production isn't justified. I think that's a long shot, you know, this area was set up to be developed. Obviously, there's tremendous political support within Alaska for this development. We talked on another show about how the Biden administration has taken a harder line on drilling in the ANWR, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. So I think it's very unlikely, honestly, that the Biden administration is going to cancel these leases. That, among other things, that would cost a lot of money. So I think this leasing actually is probably going to go forward, maybe in a way that has a less impact on this sort of sensitive Alaskan area.

DOERING: Now, as you mentioned, the company can appeal this decision up to the Ninth Circuit. In that case, what do you think we might see?

PARENTEAU: That's going to be an interesting challenge for the Biden administration. The administration could basically agree with the lower court and not appeal and say we're going to embark on a new EIS and a new review. I think, frankly, that's a good chance that the Biden administration will do that. Conoco then can try to take its own appeal. That's a complicated legal question where the federal government is the one that has the responsibility to comply with NEPA, the National Environmental Policy Act. There is some judicial decisions that suggest where the government has confessed error, the third party, here Conoco, doesn't have standing to challenge that. So that would be another, to lawyers anyway, interesting question of would the Ninth Circuit entertain a challenge to the lower court's decision where the Biden administration was not challenging it. That will be an interesting thing to watch.

In addition to the threats to Indigenous communities and the climate, the ConocoPhillips Willow project is also likely to impact the breeding grounds of the local polar bear population. (Photo:Cheryl Strahl, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: You know, in May the Biden administration threw its support behind the Willow project, despite blocking other oil and gas activity nearby in ANWR, the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. So what's the bigger picture here? And what's the administration's strategy on oil and gas leasing on federal lands?

PARENTEAU: I think the administration is sincere in saying it wants to wind down oil and gas leasing. I think that President Biden during the campaign probably exaggerated when he said he was going to end, you know. First he said, he was going to end all fracking and then he backed off and said he's at least going to end oil and gas on public lands. He's finding out of course, that that's more difficult to do than he thought. So I would not expect to see a sudden stop to oil and gas leasing. There are legitimate legal questions about how far and how fast the Biden administration can go in quote, ending oil and gas development, even on federal land, and in offshore waters, like the Gulf of Mexico and others. So what I would say is, is people have to temper their expectations about how quickly we're going to see an end to oil and gas leasing. That isn't to say, people shouldn't keep putting the pressure on, because I know they will. But I think it's probably unrealistic to expect that the administration will just announce tomorrow, no more oil and gas leasing anywhere, that's not going to happen. But I do see the curve of oil and gas production from federal land and federal water bending down. And certainly, if the administration is going to meet its targets, you know, of a electricity or an energy sector, that's carbon neutral by something like 2035 or 2040, even, they're going to have to severely curtail oil and gas development. And then, of course, as that happens, we'll have to see what Congress's response is. Not only the Congress we have today, but the Congress we're going to have after the midterm elections, and of course, ultimately in 2024.

With the recent court decision about the Willow Master Development Plan, Bureau of Land Management has a chance to actually listen to Nuiqsut residents when ConocoPhillips applies again.#SilaInuat #Inupiaq #IndigenousVoices #StopArcticOilExtraction #BuildBackFossilFree pic.twitter.com/4uWHpD1ps1

— silainuat (@silainuat) August 25, 2021

DOERING: Now, back in June, Pat, you and I had a chance to talk about this judge in Louisiana, who blocked the Biden administration's attempts to pause oil and gas leasing on federal lands and waters. And the judge basically said that it needed to go ahead and hold those lease sales. What's the status of that decision, and how is the administration responding now?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, the administration is being rather coy, is the word I would use, in response. They're saying on the one hand, we intend to comply with the judge's order.. Secretary Haaland has promised to deliver to Congress and basically to the public. A report on this review that President Biden had ordered of the oil and gas program, we haven't seen that report. It's being promised sort of virtually any day. We know that this report is going to contain proposed revisions to the oil and gas leasing program, for example, it's going to require a lot more rigorous analysis of the climate effects of all this leasing. It's going to require imposing what's called the social cost of carbon in the analysis of whether further leasing is justified. It's going to increase the amount of royalties that have to be paid for these oil and gas leases. So all of that is pointing to the in the direction of less, not more leasing. We haven't seen that report.

Former EPA Regional Counsel Pat Parenteau teaches environmental law at Vermont Law School. (Photo: Courtesy of Vermont Law School)

In the meantime, the Department of Justice just announced, not surprisingly, that it is appealing the district judge's decision from Louisiana to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. So it could very well go all the way to the Supreme Court. Some court is going to have to resolve what is the administration's obligation to continue a leasing program, at what level and with what restrictions and so on and so forth. Another really interesting area where we're going to have to wait a while to see how, as we say in Vermont, how some of this sugars off in the courts.

DOERING: Pat Parenteau is a professor of environmental law at Vermont Law School. Thanks so much, Pat.

PARENTEAU: You're very welcome, Jenni.

DOERING: As we are going to air, the Department of Justice has announced a plan to hold the Biden Administration’s first oil and gas lease sale later this year. In a statement, the Interior department said it will quote, "conduct leasing in a manner that fulfills Interior’s legal responsibilities, including to take into account the programs’ documented deficiencies". So, the Biden administration is moving forward with lease sales but they continue to fight the Louisiana ruling that requires them in court.

Related links:

- E&E News | “Court Axes Permits for Massive Alaska Oil Project Backed by Biden”

- Click to hear our last story on Judge Gleason and oil leasing in ANWR

- Listen here to our most recent story with Pat Parenteau about the legal issues with pausing oil and gas development during the Biden Administration’s first months in office.

- E&E News | “Interior Announces First Oil Drilling Sales of the Biden Era”

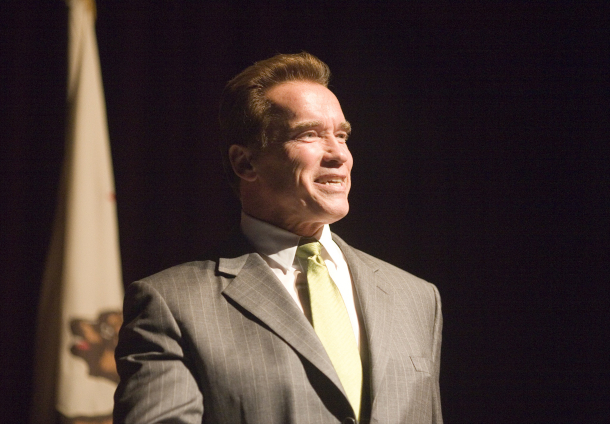

Climate and the California Recall

Gavin Newsom has been governor of California since 2019 and has pushed for environmental policies such as signing a 2020 executive order to phase out sales of gasoline-powered vehicles and require all new passenger vehicles sold in the state to be zero-emission by 2035. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: And Aynsley, while judges decide these climate questions on a federal level, voters in California are deciding the future for Democratic Governor Gavin Newsom, and by proxy, the future for climate policy in the Golden State.

O’NEILL: Oh, what’s going on there?

DOERING: Well, Governor Newsom, who’s aggressively pursuing climate action, is facing a recall election on September 14th, partly over the pandemic restrictions he’s put in place. Democratic voters outnumber Republicans 2 to 1 in the state but because of its unusual rules for recalls, the GOP sees this as the best chance for ousting a Democratic governor.That’s how Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger went “Total Recall” on Governor Gray Davis in 2003 to become “The Governator”.

Arnold Schwarzenegger was elected during the 2003 gubernatorial recall of Governor Gray Davis. The Republican governor passed legislation focused on addressing climate change like AB 32, the California Global Warming Solutions Act, making California the first state in the nation to cap greenhouse gas emissions. (Photo: Thomas Hawk, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

O’NEILL: Haha, wait, what kind of strange rules does California have that gave rise to the Governator?

DOERING: Well, the ballot asks two questions: First, should Governor Newsom be recalled, yes or no? A simple majority will decide his fate. And so far, polls put the Governor with a slim lead, but it’s within the margin of error, so it’s close.

O’NEILL: Ok, that doesn’t seem too odd so far.

DOERING: No, but here’s the thing: if he should lose, the second question asks voters to pick his successor and there are 46 candidates on the ballot. Of them, whoever gets the most votes would become the next Governor of California, even someone who earns just a few percent.

O’NEILL: Ah ha… well, what do we know about the climate records for the candidates who are leading in the polls?

DOERING: Well, frontrunner Larry Elder, a Republican, has called the climate crisis “a crock”. Also polling well is moderate Democrat Kevin Paffrath, a real estate agent who supports expanding solar and wind. There’s also John Cox, a Republican businessman who says climate change is real, but not necessarily all bad, especially for agriculture.

Larry Elder is a conservative talk radio host who has called climate change a “crock”. He’s one of the top contenders for the 2021 California recall elections, according to polling as of August 25, 2021. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

O’NEILL: Plenty of scientists would disagree with that, of course. And Governor Newsom, in contrast, has taken some big steps to address the climate crisis, right?

DOERING: Yeah, he put 14 billion dollars towards climate initiatives in the latest state budget, far more than many states, and he’s steering California towards an end to gas car sales by 2035. And, those investments can have a huge impact. If it were an independent nation California would have the world’s fifth largest economy. So, what happens in California on these issues can ripple beyond the state. And regardless of the outcome, some will see this as a referendum on climate. Whatever happens in this race, we’ll be sure cover it after the election on September 14th.

O’NEILL: Sounds good, thanks Jenni.

Related links:

- E&E News “Newsom loss would test Calif. climate policies”

- The Washington Post “How California’s Gavin Newsom could lose his job to a Republican in a recall”

[MUSIC: Will Lyle, “Rains of Change” on Source Codes, by Will Lyle, self-published CD]

DOERING: Coming up – New research finds nearly 300 chemicals increase hormone production in women, elevating the risk for breast cancer. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stick around!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Stephanie Trick and Paolo Alderighi, “Stephanie and Paolo’s Boogie”]

Note on Emerging Science: Oh, What a Tangled Web They Weave

A banana spider in its neurotoxic web. (Photo: Under the same moon, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Just ahead, a scientific breakthrough that may help reduce mosquito borne illnesses but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

LYMAN: It’s long been assumed that spider’s webs were merely sticky traps that captured prey. But new research suggests that the webs of some species of spiders may actually contain neurotoxins that paralyze prey. Researchers in Brazil, first suspected some 25 years ago that the webs of the orb weaver spider, contain neurotoxins, when they observed freshly entangled prey like bees and flies convulsing, a possible symptom of neurotoxin poisoning. Scientists recently analyzed the genes and proteins in the silk glands of banana spiders, a species of orb weaver and found proteins that resemble known neurotoxins which may turn the spiders’ webs into “paralytic traps.” In fact, scientist were able to isolate the proteins and and injected them into bees, which caused the insects to become paralyzed in under a minute, confirming their suspicions about the neurotoxic quality the webs. And researchers believe the webs of other spider species probably have similar neurotoxins. Next on the scientists’ research agenda is looking into the possibility that smaller unidentified proteins the researchers found in webs may help keep the spiders’ prey alive until the spiders are ready to feed. Oh, what a tangled web they weave. That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

Related links:

- Science News | “Some spiders may spin poisonous webs laced with neurotoxins”

- Read the journal article in the Journal of Proteome Research

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

‘Mosquito-Borne’ No More?

Dengue virus is spread through the bite of an infected mosquito. According to the CDC, 40% of the world’s population live in areas with a risk of dengue. (Photo: Sanofi Pasteur, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

[MOSQUITO BUZZ SFX]

DOERING: They’re not just annoying. Mosquitoes are the most efficient disease transmitters on the planet, killing more than 1 million people every year according to the World Health Organization. But a tiny and unlikely hero could help in the fight against diseases like zika virus and yellow fever. It’s a type of bacteria called Wolbachia, and it makes mosquitoes much less likely to carry and transmit disease. Scientists at the World Mosquito Program recently reached a breakthrough in a trial that used Wolbachia to try to combat the virus that causes dengue fever. They released mosquitoes infected with Wolbachia into parts of an Indonesian city and saw a huge drop in dengue cases in those neighborhoods. Scott O’Neill is the founder of the World Mosquito Program and joins me now from France. Welcome to Living on Earth!

O'NEILL: Hi, it's a pleasure to be here with you.

DOERING: So tell me about how you and your colleagues developed this technique of using the Wolbachia bacteria to combat dengue fever.

O'NEILL: Yeah, so I was very interested in the properties of Wolbachia, which enabled it to be able to spread into a wild mosquito population and maintain itself. And we spent a lot of time working out how to transfer Wolbachia into mosquitoes. So it was stably maintained. When we got it into the mosquitoes, we found out by chance that it actually prevented a range of viruses from growing, replicating in the body of the mosquito, and they can't grow in the body of the mosquito, they can't be transmitted to people: dengue fever, Zika, chikungunya, yellow fever, all these viruses transmitted by the same mosquito couldn't grow.

DOERING: How does this Wolbachia bacteria actually push out the viruses?

O'NEILL: Yeah, so what it does is it stops them from replicating. And we think it's doing that in a couple of different ways. Most importantly, it's competing for key resources that the virus needs to be able to produce more copies of itself. And as a result, the virus doesn't grow as well, if this Wolbachia is in the insect, and if it doesn't grow, then it can't get spat out again when it bites somebody in its saliva, which is how people get the virus transmitted to them. So it's a natural way in which we can completely stop transmission of a whole range of viruses simultaneously.

DOERING: Right. So this is a really common bacterium in nature, but it wasn't already in mosquitoes.

O'NEILL: That's right. So it occurs naturally, we estimated around 50% of all insects and bees, or butterflies, all sorts and including a number of mosquitoes. But it didn't occur in this one mosquito that transmits all these viruses to people. And so the work of my laboratory for many years was involved in transferring it into that mosquito so that it would maintain itself there, which we were ultimately successful at doing.

DOERING: How did you tweak it over the years?

O'NEILL: Oh, you know, it's, it's a long and complicated story that took us many years of different approaches of, you know, at the end, we needed to inject it into mosquito eggs that have been laid and handled in a certain way with certain needles with preparations of or Wolbachia extracted from a fruit fly. And took us many, many years. But once we had done at once, we were able to have a colony of mosquitoes and with the discovery that it would prevent the transmission of these viruses. We then embarked on a program where we wanted to release mosquitoes that contain this fall back here into the wild, where they would then breed with wild mosquitoes and pass the Wolbachia into that population of wild mosquitoes and it would spread naturally and maintain itself.

According to the studies by researchers at the World Mosquito Program, infecting mosquitoes with the Wolbachia bacteria can reduce the incidence of dengue, Zika, chikungunya and yellow fever. (Photo: Master Sgt. Brian Ferguson, U.S. Air Force Photo, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: So I understand you've tested this first in Australia, and then Yogyakarta, on the Indonesian island of Java, where dengue is very common. So how did you go about testing this in Indonesia?

O'NEILL: Yeah, so we collaborated with a local university in Indonesia, but also with scientists in other parts of the world, including UC Berkeley, for statistical assistance with the trial. And we took the city of around 400,000 people and we cut it up into 24 areas. Of those 24 areas, 12, or half of them got the Wolbachia release of mosquitoes and the other half didn't. After we let the Wolbachia into the mosquito population, and it had established, we then turned on surveillance for disease in healthcare clinics throughout the city. And we were looking to see the people that came to health care clinics if they were tested and found to be positive for dengue. Did they live in a Wolbachia area? Or did they live in an area that didn't receive Wolbachia? And what we found is that there was a 77% reduction in the number of dengue cases in people that lived in Wolbachia areas, and an 86% reduction in hospitalizations if you lived in a Wolbachia area. We're very delighted about that. But it's good to understand that in this sort of trial design, they're probably an underestimate. And the reason is that, you know, even though you might live in a Wolbachia area, you might not spend your whole time there, you might get on your motorbike and go across into a neighboring area to go take your child to school or to go to the market and you could catch dengue there. So we think that the true impact we're having on things is bigger than the 77%, we measured. And we've now covered the whole city, we've filled in the control areas so that all the people within Yogyakarta got to benefit from it, from the intervention. And now we're waiting to see with the large coverage, whether we actually eliminate dengue transmission completely from Yogyakarta in upcoming years.

DOERING: So how did you actually gain the community's trust? I mean, you were proposing to release live mosquitoes right next to their homes with this bacterium that maybe you know most people don't haven't have never heard of don't know much about.

O'NEILL: We spent a lot of time doing engagement with communities, talking to communities about what we're doing, listening to their concerns and answering those concerns. And when we work in an authentic way with communities, we find that communities are very supportive. And I think part of the fundamental reason for that is that people are fearful of dengue and fearful of their children getting sick and potentially dying of dengue, and not really having any effective treatments at the moment. And so given that risk, people seem to be quite willing to try out something novel.

DOERING: Right, I understand Dengue fever is a pretty serious disease. What is it like when someone comes down with this?

O'NEILL: It can be terrible for people. If it doesn't kill you, which it does to many people, you know, it's a spectrum of disease, sort of, like we're seeing with COVID. You know, some people die, and some people have mild disease, it's the same with dengue. If you have a bad dose of it, you know, you have these piercing headaches, have a metallic taste in your mouth, a rash on your body, you're vomiting, you can't get out of bed to go to the toilet. People will describe it as one of the worst couple of weeks of their lives. So it's quite devastating for communities, hospitals fill up people can't go to work. It has a big social and economic costs as well as a direct health cost.

In 2016 Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes were released over a six-month period throughout parts of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. After several years of trials rates of dengue were 77% lower in the research areas compared to areas that did not receive mosquitoes. (Photo: Master Sgt. Brian Ferguson, U.S. Air Force Photo, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: So how likely do you think it is that Wolbachia could someday help completely eliminate dengue?

O'NEILL: Well, I think we're probably going to need multiple tools. You know, it's such an entrenched problem, up to 400 million people being infected every year, all the top major tropical cities of the world at risk of dengue. Probably any one tool by itself may not be sufficient to completely eliminate, but a combination of tools and a concerted effort to work on dengue elimination, I think we should be able to make great headway in the future to reducing disease. Certainly, where we're releasing more back here and putting it out, we're seeing elimination of local disease, we'd love to see the methods scaled up enormously around the world to benefit communities. And so we're hopeful that in the coming years, we'll see an expansion but just because of the size of the problem, it's going to take many years.

DOERING: Scott O'Neill is the founder of the World Mosquito Program. Thank you so much, Scott.

O'NEILL: Yeah, you're very welcome. Thanks for having me on.

Related links:

- The Atlantic | “A Pivotal Mosquito Experiment Could Not Have Gone Better”

- Nature | “The Mosquito Strategy that Could Eliminate Dengue”

- Learn more about the Wolbachia-mosquito studies carried out by the World Mosquito Program

[MUSIC: Raquel Cepeda, “Berimbau” on Passion – Latin Jazz, by Baden Powell and Vinicius de Moraes, Raquel Cepeda Music]

Chemicals and Breast Cancer Risk

Estrogen is a female hormone made mainly in the ovaries. From the first monthly period to menopause, estrogen stimulates normal breast cells but a higher lifetime exposure to estrogen may increase breast cancer risk. (Photo: Healthy mind and Kat, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

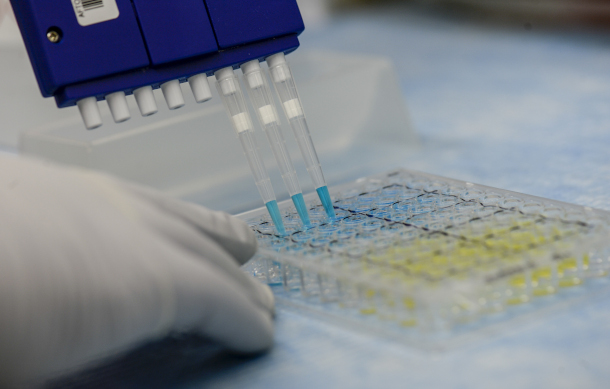

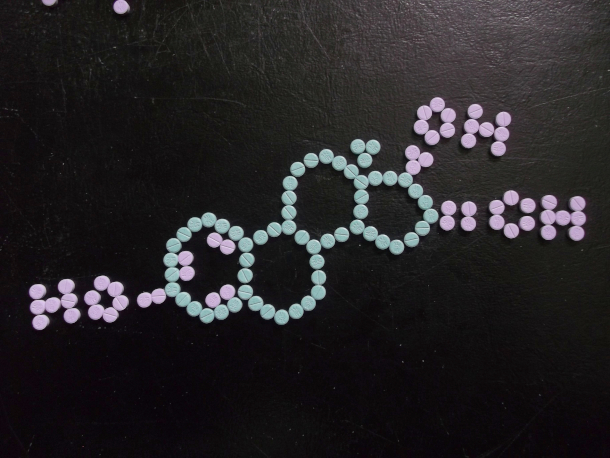

O’NEILL: Roughly one in eight American women will develop breast cancer in their lifetime, according to the American Cancer Society. And breast cancer rates are on the rise, up half a percent each year for the last several years. A link between breast cancer and the naturally occurring hormones estrogen and progesterone is well known. Higher levels of these hormones lead to a greater risk of developing breast cancer. So, women who start puberty early or enter menopause late are exposed to more estrogen over the course of their lives and are at increased risk. What’s been less well understood is how chemical exposure can actually raise those hormone levels in women. But researchers at the Silent Spring Institute recently concluded a study that looked at 1800 chemicals listed on the EPA’s toxicity forecaster, ToxCast, to see which ones caused an increase in estrogen and progesterone. They found nearly 300 chemicals increased one or both of the hormones, elevating the risk for breast cancer. Elizabeth Gribkoff, is a reporter for Environmental Health News, and has been covering the latest research.

GRIBKOFF: So, a little bit of background first: historically, a lot of chemical safety assessments have been done using animal studies. And that kind of makes sense. The idea is like, we'll see how mice or whatever respond to chemicals and that can kind of give us a window into how humans might respond. The only challenge is that that's pretty expensive and time consuming. So increasingly, regulatory agencies have been looking at basically doing like en masse chemical safety testing, where they'll like, expose cells and other molecules to, you know, a large array of chemicals, and then see if that triggers any changes. So the EPA had done that and released data on like, almost, I think about 2000, chemicals, in 2018. So Silent Spring, researchers essentially looked through that existing data and saw which of those chemicals cause cells to make higher levels of estrogen and progesterone, and they found 296 chemicals that did that.

About 1 in 8 American women will develop breast cancer over the course of their lives. (Photo: Marco Verch, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

O’NEILL: Now, that's a very particular definition of how these are harmful. But had any of these chemicals previously been identified as harmful? Say, were any of them carcinogens?

GRIBKOFF: Yes, so 77 of them had previously been identified as carcinogens, and some other ones had previously been found to be potential reproductive toxicants as well. But another kind of key finding was that they noticed that a lot like over 200 chemicals, you know, hadn't been identified previously as potential carcinogenic, and a lot of them hadn't even really been looked at. You know, it wasn't like they'd been studied for that potential have been found to be safe. It was just more that a bunch of the chemicals had never really been there, safety hadn't really been screened.

O’NEILL: In the United States, safety screening for consumer products rarely looks at how the chemicals affect the production of estrogen and progesterone. Could you share with us any insights as to why you think this might be?

GRIBKOFF: You know, historically, a lot of women's health issues have often been underfunded, or for whatever reason haven't been taken quite as seriously. Researchers also told me that a lot of existing chemical safety tests didn't really look at effects to the mammary gland or dismissed those effects when they were found. And one of the researchers I talked with said, You know, I can't help but kind of wondering if this is because a lot of women's health issues have gotten short shrift.

The Silent Spring Institute found toxic chemicals linked to higher hormone levels in common products, including pesticides. Gribkoff suggests that consumers purchase organic foods or thoroughly wash their foods to reduce the risk of exposure to harmful chemicals. (Photo: Departement des Yvelines, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

O’NEILL: And when these issues are getting overlooked, what can sort of be done in order to remedy this problem?

GRIBKOFF: Yeah, I think there's a few different steps. I mean, you know, the research and the study said that this was of 296 chemicals, this kind of provides a good starting point for, hey, we might need to, you know, look at these chemicals further, maybe we should really be looking at could these affect mammary tissues, maybe we should be in larger scale epidemiological studies, when you're actually looking at, you know, population level exposure, maybe these should be chemicals that we should be seeing whether you know, women who are exposed to these are having higher rates of breast cancer. And I think just in general, when we have, say existing chemical safety screening data, we should also be looking at whether chemicals could be causing cells to make more estrogen and progesterone. And I think something that's kind of interesting is that I guess in toxicology research, toxicologists have already been looking at hormone mimicking effects, like whether something chemical could be mimicking estrogen, but for whatever reason, haven't been looking as much at hey, can this actually cause cells to make more estrogen. So it just seems like that needs to be, I think that is becoming more of an area of focus, but continuing to do that. And just also, you know, not dismissing effects to the mammary gland, if that's found in a chemical safety test.

O’NEILL: And Elizabeth, let's chat a little bit more about these couple hundred of chemicals. They've been found in common places, such as hair dye and pesticides. How common exactly are these chemicals and what consumers are being affected?

Chemicals linked to breast cancer include everything from substances in anti-aging creams, to bisphenol A in canned foods, to flame retardants. (Photo: Maro Verch, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

GRIBKOFF: Sure. So I think that that's something that researchers still need to get something of a better handle on one of the researchers I talked to said, you know, she wasn't exactly sure how consumers were being exposed to all of these. But I mean, something, you know, a lot of them are pesticides. So one way people could kind of, you know, maybe reduce exposure, that would be eating organic food, making sure that you're, you know, washing fruits and vegetables adequately. And of course, for farm workers, you know, making sure that they have adequate protection when they're working in the fields, that they're not getting exposed to these chemicals. And then, you know, in general, even before this study happened, there's been research showing that, you know, there's a lot of like hormone mimicking chemicals in personal care products, especially those marketed toward Black women. So that's just something that people when you go to the store and you know, buy whatever shampoo, you think, Oh, it's going to be safe. Well, unfortunately, that's not necessarily the case. So Silent Spring actually has this app called Detox Me that people can use. And I think that's probably easier for people that you can actually go and like scan a product barcode, that's probably easier than trying to remember in your head, you know, which specific chemicals you know, are going to be in which product. And Environmental Working Group also has this skin deep database that has where you can kind of go and look up, you know, sunscreen or whatever to see if it's safe. So there's, you know, ways out there that consumers can kind of take measures to protect their own health. Obviously it would be better if these products were tested before they got to market so that people actually knew that what they were buying was safe, but that's not how it stands currently.

O’NEILL: Elizabeth Gribkoff is a reporter for environmental health news. Elizabeth, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

GRIBKOFF: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News “Breast cancer: Hundreds of chemicals identified as potential risk factors”

- More about Silent Spring’s app “Detox Me,” which has tips to prevent exposure to toxic chemicals

- The Skin Deep database from the Environmental Working Group

[MUSIC: Tanya Dennis, “Slow Reckless Tango” on White Sails Blue Skies, by Tanya Dennis, Paloma Records]

DOERING: Coming up – July 2021 was the earth’s hottest month ever recorded. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Saturday Night Live Band, “Boiler Room Inspection” on The Saturday Night Live Band-Live From New York, by Leon Pendarvis/arr.Leon Pendarvis, ProJazz]

Beyond the Headlines

July 2021 broke the record for Earth’s hottest month. (Photo: Damian Gadal, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

Well, it’s time for a trip Beyond the Headlines now with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org and daily climate.org and he’s in Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter. What do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: We're gonna look back the month of July, which is now officially Earth's hottest month on record here in the US. We had record ridiculous temperatures. Last month, July 2021, was almost 1.7 degrees Fahrenheit, above the average July temperatures throughout the 20th century, another very convincing fact on the path to establishing that we're already in the grips of global warming.

O'NEILL: Wow, I know the previous record holder was a three way tie July 2016, July 2019, July 2020. It's scary to think that we've now surpassed that.

DYKSTRA: And of course, all those three years were in the last five or six years, kind of tells you there’s pattern developing. And here in the Northern Hemisphere, the record was shattered even more. July 2021, 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit, warmer than any of the average years of the 20th century. Think of all of the disasters that have happened that are unprecedented. There are symptoms of a warming planet, and we're not even beginning to deal with climate change.

Steel production contributes roughly 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions. The promise of “fossil fuel free” steel from Swedish company Hybrit could be a significant step forward in efforts to slash global emissions by mid-century. (Photo: Yasin Hm, Unsplash)

O'NEILL: Yeah, all of those natural disasters that we've been predicting all this time. I'm a little afraid to ask, but how do you think some of the Arctic sea ice might be doing?

DYKSTRA: We'll see how it's doing. It doesn't look like it's in very good shape at all. The middle of September September 15th, traditionally, is the date for the annual low point for melting Arctic sea ice. In recent years, we've seen both the Northwest Passage, the fabled route over northern Canada for shipping, and the Northeast passage, which goes up top from Russia and Siberia, open up and, in a tragic irony, a lot of that shipping potential is going to be moving oil and gas from Russia to other countries and shipping from Europe in the US to the Pacific Rim.

While the boll weevil brought devastation to Alabama’s cotton crops a century ago, it helped Enterprise, Alabama, a town which had diversified its crops before the pest’s introduction, prosper. The town’s statue of a Greek goddess holding a boll weevil is one of the nation’s most unique monuments. (Photo: US Library of Congress)

O'NEILL: Well, Peter, do you have anything a little more uplifting for us?

DYKSTRA: As a matter of fact, I do. There's a potential breakthrough in the field of making steel steelmaking accounts for roughly 8% of the greenhouse gases being entered into the atmosphere. And a Swedish firm called Hybrit is looking to cut back on using coal and coke, eliminating them completely. They've been used historically, to heat the super hot kilns used in steel mills. full production, according to the company is expected by 2026. And there's a rival Swedish company saying there'll be online by 2024. So climate help may be on the way in one of the dirtiest industries out there steel making.

O'NEILL: Peter What do you have for us from the history books for this week.

DYKSTRA: 3rd of September, 1910, Alabama's state entomologists makes the feared announcement that boll weevils, these cotton destroying pests, have been found. And the crop loss that occurred then and into the 1930s in the depression, ruined a lot of farmers in the south, except in one Enterprise, Alabama, where they've actually erected a statue, a Greek goddess holding a boll weevil, in the center of town, where the Confederate veteran statues are usually found and are now very contentious.

O'NEILL: Honestly, Peter, I can't say I've ever heard of a statue with a boll weevil on it before. What happened that made enterprise want to erect a statue commemorating it?

DYKSTRA: The reason that the people of enterprise like the boll weevil is that they had the foresight to get out of cotton farming, and many of their farms, just as the weevils hit, they moved to diversify. Other crops were grown, mainly peanuts. Enterprise kept thriving, while other towns were down. And nobody's talking about removing the boll weevil statue from the center of town.

O'NEILL: Well, thank you, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with environmental health news. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Thanks again and we'll talk to you soon.

DYKSTRA: All right. Aynsley. Thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

O'NEILL: And there's more on these stories at the living on earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- NOAA | It’s official: July was Earth’s hottest month on record

- CNBC | “‘World’s first fossil-free steel’ produced in Sweden and delivered to Volvo”

- Smithsonian Magazine | “Why an Alabama Town Has a Monument Honoring the Most Destructive Pest in American History”

- Read more on Environmental Health News

- Check out The Daily Climate

[MUSIC: Tex Ritter, “Boll Weevil Song” on Capitol Collectors Series, by Tex Ritter, Capitol Records Nashville]

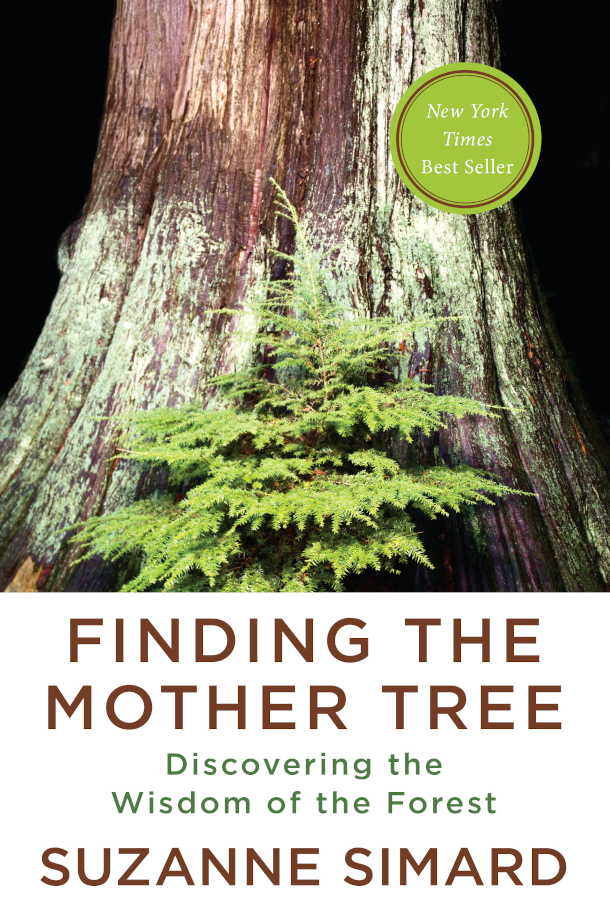

Finding the Mother Tree

“Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest” takes readers into the field with Suzanne Simard as she describes her forest experiments and shares how her findings helped her through the challenges of motherhood and a cancer diagnosis. (Photo: courtesy of Knopf)

DOERING: Walking in an old growth forest like the towering Sequoias in California can be something akin to a spiritual experience for some. Ancient forests thousands of years old, are awe-inspiring but no less impressive is the complicated network of life beneath the soil that we can’t see. There, an intricate web of roots, insects, fungi, and bacteria is teeming with life, and contains twice as much carbon as the trees themselves. The soil fungi called mycorrhiza create a complex “wood wide web.” It’s how ancient “Mother trees” and other plants can send nutrients and warning signals back and forth for the benefit of the entire forest ecosystem. In her new book, “Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest,” ecologist Suzanne Simard reveals what she’s discovered about these connections through decades of experiments with trees. She teaches forest ecology at the University of British Columbia and joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Suzanne!

SIMARD: Thank you, Jenni. It's good to be here.

DOERING: So, you just really have this way of looking at a forest and seeing so much more than I think most of us ever do. Where do you trace your connection with the forest back to?

SIMARD: Well, I grew up in forests. So you know, I live in a province of forests in British Columbia, and there's so many different kinds, but I grew up in what are called the inland rain forests, beautiful, huge trees, cedars, and hemlocks, Bruce's larches. birches, it's very, very species diverse forest for the Pacific Northwest. And so I grew up there, my great grandfather, my grandfather, my dad and uncles were all horse loggers, and seeing how, you know, how to live in forests and make a living out of it without actually destroying the forest.

DOERING: It sounds like understanding the forest being in the forest is in your blood.

SIMARD: Yeah, well, it is. It's also in my DNA, because it was like multiple generations of families doing this, our family doing this. So yeah, I kind of grew up with it in my background, and my blood, my bones, my DNA.

DOERING: Well, what got you curious, in a scientific way about the connections between trees and the rest of the forest?

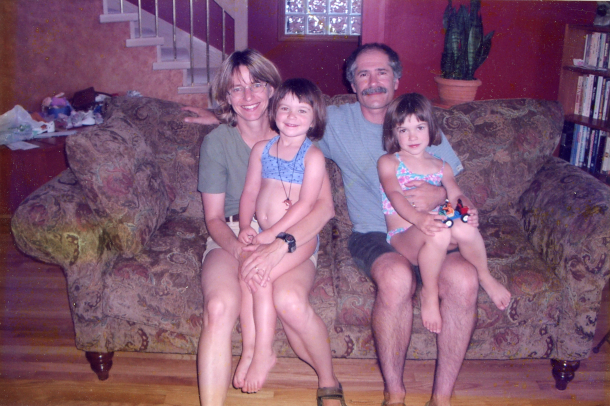

Simard grew up in the forests of British Columbia and often camped with her family. Left to right: her brother Kelly, three; sister Robyn, seven; mother Ellen June; and five-year-old Suzanne. (Photo: courtesy of Suzanne Simard)

SIMARD: Yeah, so after I grew up, I became a forester, myself. And when I entered into the forestry profession, at the age of 22, I started to learn that, you know, when I grew up with my grandfather, horse logging wasn't at all what the forest industry had become. It had become, you know, this clear cutting machine that wouldn't just take out the odd tree here, and there wasn't selective logging, it was clear cut logging. And that means, you know, taking every tree out, and my job at the time was to replant these forests, with trees, seedlings and try to help them recover. But what I found was that, you know, when you don't have you know, surrounding trees, and good soil, that it's harder to get trees growing. And so I saw this and the practices that were getting hold like herbiciding the native plants to get rid of them to make way for these trees that we were planting to give them a better shot at sun and light, and water, actually was having, you know, a detrimental effect on the trees. So the trees actually seem to need these native plants around them as part of their successional process of, you know, healing the land. And that was that what I was seeing that started to get me to look below ground at what we might be doing wrong.DOERING: So you noticed as a forester, when you were trying to help these plantations succeed, you noticed that they just weren't regenerating very well. They weren't healthy. They didn't seem like they were going to survive. How did you then go about trying to figure out what could help them survive?

SIMARD: Yeah, so one of the things I noticed, you know, some trees would do really well, but others would suffer from pathogens and insect infestations, and especially a root pathogen was infecting a lot of the Douglas firs and it would spread from fir to fir to fir and affect the whole plantation. And so I thought, well, if it's a root pathogen, I need to look below ground at what's going on here. And these root pathogens, these fungal pathogens, really were attacking the big roots of the trees and then girdling them in other words, infecting the base of the tree, and then they would just die within a year or two. And so I thought, well, we're disrupting the soil balance. So I started looking at the fungal communities below ground, there's thousands of species of fungi, you know, there's kind of three or four main groups: there's pathogens, like I mentioned, that kill trees, there's saprotrophs, which decay stuff, and there's mycorrhizal fungi, which are helper fungi. Which by the way, mycorrhiza literally means fungus root. It's a relationship, a symbiotic mutualistic relationship between trees and fungi, where the tree provides photosynthate or carbon energy to the fungus. The fungus then uses that energy to grow mycelium through the soil. And as it does that, it kind of coats all the particles and soil pores and draws out the nutrients and delivers it back to the plant or the tree in exchange for this photosynthate. So they both are benefiting from this. And I learned in my research that these fungi can actually connect trees together, they can connect trees of the same species, they can even connect trees of different species. And I found out that in my research that paper birch, which was a target of these herbicide treatments, because it's shading the fir.

A clearcut in British Columbia. (Photo: meaduva, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

DOERING: It's a competitor.

SIMARD: Yeah, as a competitor, that it actually was connected to Douglas fir, and delivering carbon to Douglas fir, which, you know, we hadn't thought of that before. And that kind of changed the equation then like it's not just a competitor. It's actually also a collaborator at the same time.

DOERING: What could your discovery of how carbon moves between trees with the help of fungi mean for our climate change efforts?

SIMARD: Lots and lots. So for one forest cover a third of our terrestrial land base, they contain about 80% of our terrestrial carbon. And so they're hugely important in the carbon budget. And of course, we know carbon is sort of, you know, a key indicator of climate change. And so forests are important in this, anything that happens to forests affects the global carbon budget. And we are affecting our forests every single day. What my research shows is that keeping these old forests, these old trees, the mother trees, which are sort of the linchpins, or the nucleus of the recovery of forests from any kind of disturbance, whether it's fire or logging or insect infestations, these old trees are essential in the recovery of the forests in the regeneration of the forest. But they're also really important because these old forests, especially old growth forests, which are you know, basically the most ancient forests, they store so much carbon in the soil in their trunks. And they're also rich in biodiversity, the fungi in the soil, they support the lichens in their crowns, the birds that use them and the animals, so on these old forests are hubs of biodiversity. But we're logging them at this incredible rate right now. In where I live in British Columbia, we really only have 3% of our valley bottom, huge old growth forests left. And this isn't just happening in British Columbia, it's happening around the world. The other thing that my research shows is if we're going to log, which we're going to continue to do, but we can focus our logging in areas where it's not so impactful on biodiversity and carbon budgets. But where we do it, to leave the old trees behind, you know, don't just take them because that is, you know, historically, that's what we've done. We, we high grade the biggest trees, but it turns out, they're the most important trees in the recovery of the ecosystem. So the harvesting shouldn't be clear cut harvesting, like we're practicing worldwide now, it should be selective harvesting. It should be leaving these old trees behind to facilitate the recovery of the forest.

As a young forester, Simard noticed that the seedlings planted after a clearcut were often sickly, and her observations prompted a whole career of research on mother trees. (Photo: © Bill Heath)

DOERING: So you write, that these fungi that connect trees in a forest might be able to evolve and adapt much faster to a changing climate and help the trees adapt too. So how could that work?

SIMARD: Yeah, that's a great question. Um, so you know, trees, of course, they're the foundation of the forest. They're photosynthetic. They're what links carbon in the sky to carbon in the soil, they convert light energy to chemical energy and drive all of our cycles. So whatever happens to trees, happens to all of us. And so really, to keep the biosphere in balance, we need to maintain forest cover across the globe. And we're losing it really quickly, you know, not just because of logging, but wildfire and insect infestations that are driven by climate change. And so trees are not going to be able to migrate or adapt as quickly as they need to, to keep up with the velocity at which climate is changing. So what is their other choice? Well, a lot of them are going to die. And we're seeing that. And yet, you know, because you know, evolution and trees take so long but evolution and fungi doesn't take as long fungi have a shorter lifespan, right, they reproduce within a year, they can mutate and be different from one year to the next. And so they can actually serve as an interface between the rapidly changing climate and the more slowly changing trees. And so the one way that we can sort of capture that adaptation or adaptability of the fungi is to make sure that trees have their appropriate microbiome, which is the fungi, the bacteria that have short lifespans, short life cycles are healthy in the soil. And that can help the trees survive, and possibly migrate a little bit further. The other thing that we need to do though, is we need to assist the migration of trees and the fungi, to keep up with the velocity of climate change to make sure that in the new environments that they're in, that they're able to cope as best as they possibly can.

DOERING: Your book, "Finding the Mother Tree" is also a memoir. How does your quest to understand mother trees resonate with your own experience of motherhood?

Simard and her family in 2005. (Photo: courtesy of Suzanne Simard)

SIMARD: That's a great question. So I wrote the book because I wanted the science to get out. But I also wanted to show that science is such a personal journey, right? It's not something to be distrusted. It comes from us. It comes from our hearts, it comes from our curiosity, to make sense of our world. And, you know, the work that I did was a reflection of my life. And so I started, the questions that I asked came from my experiences in the forest, but also as a mother, myself, and I found that the trees told me about motherhood. And I informed my research about looking at motherhood in forests, or the role of nurturing and forests, because I was going through that myself. And the role of, for example, sickness as well, I had breast cancer and I wanted to understand what if an old tree is sick and dying? What happens? Is there a connection with their kin, their children? And can that inform how I'm going to respond to this? And so, actually, when I got breast cancer, I set up a series of experiments with my graduate students saying, What if a mother tree is sick? What if she's injured? What if a mother tree is dying? And we found that these dying mother trees would actually send warning signals to her own kin more so than strangers, as well as provide more carbon energy to those kin seedlings so that they could grow bigger networks and grow healthier and stronger. And that sort of was a way of those trees of passing on their life energy into the next generations. It's a very Darwinian, in a way, it's survival of the fittest. Honestly, I don't think I would have asked those questions if I hadn't gone through this experience myself. The trees have taught me so much. And of course, when I learned this, I was already, you know, passing things on to my kids in case I didn't make it. And then I did make it, but I learned a lot about, about the importance of, of where to put your energy when the stakes are really high.

Suzanne Simard has published over 200 peer-reviewed articles and her work has influenced filmmakers (the Tree of Souls in James Cameron’s Avatar). Her TED talks have been viewed by more than 10 million people worldwide. ( (Photo: © Diana Markosian)

DOERING: Before you go, Suzanne, what you've been able to uncover in the forest is really profound, these deep connections between all the species in the forest. You say that we don't have to be a forestry scientist to deepen our own connections with the natural world. So how can we try this at home?

SIMARD: Yeah, I mean, there's so many things you can do. So I mean, the first thing is just being reconnected with your trees, your plants, what you have around you, most of us have access to some kind of natural plant community, and just being with them helps you to reconnect. And when you get that connection back, then you'll fight for the forest. So that is the absolutely the first step. You know, it's like falling in love. You know, once you fall in love, you care for that person and you keep, you know, you nurture that relationship. It's the same thing with your connection with forests. And then from there, the actions you can take, of course, you know, you can make choices like don't buy, you know, furniture that's from a tropical tree that's endangered, try to reduce your consumption of cardboard and toilet paper and paper products, making choices as a consumer. And that sends a strong message to the companies that are logging forests, you know, making sure that they're sustainable practices. And you can do that by looking at you know, certification, which has its own flaws, but in a sense, you have a lot of power as a consumer to boycott those companies that are basically mining forests. And then of course, the next step is to become beyond that is to become active in the change itself, the change makers, the ones that are on the lines, maybe a protester, or maybe a writer, or you know, doing interviews like this, those are all important steps as well. Getting the word out educating, getting people aligned so that we all care and fight for our planet because we need it to survive.

DOERING: Suzanne Simard is a professor of forest ecology at the University of British Columbia and the author of "Finding the Mother Tree." Thank you so much, Suzanne. Thanks, Jenny. That was great.

Related links:

- Find the book “Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest” (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Author Suzanne Simard’s website

- Learn how to get involved with the Mother Tree Project

- Watch Suzanne’s popular TED talk, “How Trees Talk to Each Other”

[MUSIC: Shubh Saran Hmayra, “Haze” on Hmayra, Art of Life Records]

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Anna Canny, Jay Feinstein, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Joshua Siracusa, Tivara Tanudiaia, Tom Tiger and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Jake Rego engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering

O’NEILL: I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth