Reining in Methane

Air Date: Week of November 5, 2021

Gas flares such as the above burn off methane gas, converting it into carbon dioxide, before releasing it into the atmosphere. CO2 and methane (CH4) are both greenhouse gases, but methane is roughly 80 times more potent over the near term. (Photo: WildEarth Guardians, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The U.S. oil and gas industry leaks millions of tons of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere every year. New Environmental Protection Agency rules propose to strengthen requirements for industry to prevent, identify, and repair methane leaks, as science says methane emission reductions will quickly help put the brakes on planetary warming. Harvard Law Professor Jody Freeman joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the rules and why tackling methane emissions can make an immediate difference.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood

When it comes to global warming, methane is like CO2 on steroids. Over time methane decays to CO2 but when it is first released into the air methane is about 80 times more powerful than plain carbon dioxide. Methane of course is the principal active ingredient in natural gas, and hydraulic fracturing releases a lot of methane that is captured and sold. But there are a lot of leaks from the natural gas pipe systems and oil wells and coal mines also release a lot of methane that is not captured. These so-called fugitive methane emissions add up to close to a third of the climate forcing that is raising temperatures right now around the world. Without any major federal climate legislation so far in the United States President Biden went to Glasgow to say the US is adopting stringent rules and joining with other countries to fight climate disruption from super-warming methane.

BIDEN: Together with the European Union, we're launching a global methane pledge to collectively reduce methane emissions, one of the most potent greenhouse gases, by at least 30% by the end of the decade. It's the simple, most effective strategy, we have to slow global warming in the near term.

CURWOOD: The White House has issued plans to reduce methane from landfills and food production, but the biggest move so far is an EPA regulation now in the works that would require oil and gas producers to capture methane. They say the EPA rule alone could reduce methane emissions by about 41 million tons through 2035, which would have the climate benefits of taking 200 million cars off the roads for a year. Joining us now is Harvard Law professor Jody Freeman who served as Counselor for Energy and Climate Change in the Obama White House. Jody, welcome back to Living on Earth!

FREEMAN: Great to be with you, Steve.

CURWOOD: Give us a primer about why methane matters so much, right now.

FREEMAN: Well, it's a big deal, because methane is responsible for about 30% of the global warming we're experiencing. And cutting methane is the single fastest, most effective opportunity to reduce climate change risks in the near term. Unlike carbon dioxide, its warming power doesn't come from a gradual build up over time. It's almost entirely from recent emissions. So by reducing methane, now, we can reduce warming that would happen in the near term; it has almost an immediate beneficial impact.

CURWOOD: So interestingly, Jody, the United States has never actually legislated climate change in a big way. We've never really had the laws out of Congress to do this. So it's been up to executive action to address climate disruption so far. So how significant is this announcement from the Biden administration about rules to address domestic methane emissions?

FREEMAN: Well, you're right, Steve, Congress has never passed a comprehensive climate bill. And the Obama team tried to get that done, got it through the House, but didn't get it through the Senate; Biden tried to get a big plan to reduce carbon from electricity through the Congress, doesn't look like that'll pass. And if you remember, back in the day in the Clinton administration, he tried to adopt a BTU tax, which would have reduced emissions too and that went down to spectacular defeat. So in that historical context, what presidents have to use is their executive power. And they use the agencies they've got, primarily the EPA, which implements the Clean Air Act. And it's that authority that EPA used to establish this new methane rule. And it's a really big deal. First of all, it regulates everything in the oil and gas chain: production, processing, transmission and storage. And oil and gas is the largest industrial source of methane emissions. So it's a big target for the agency. And there are really meaningful reductions that they can get. The estimate is that by 2030, this proposal would reduce methane emissions from oil and gas sources by about 75% compared to 2005 levels.

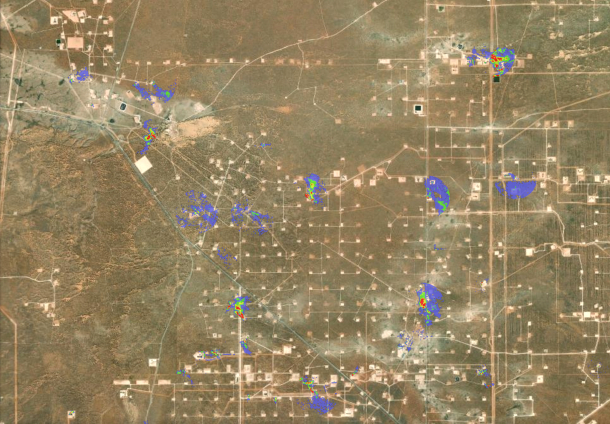

Methane plumes in the New Mexico portion of the Permian Basin oil and gas fields, from remote sensing data gathered during September and October 2019. (Image: Derived from JPL/NASA Methane Source Finder)

CURWOOD: How far would these methane emission reductions get the United States towards its overall commitment in the Paris process?

FREEMAN: Well, it's hard to put an exact number on that. But it's a significant policy that would make real progress, I think we can confidently say. It's hard to get percentages right now, because there's so many proposals that have been made that aren't final. You've got to think about the proposal to cut transportation sector emissions that came out of EPA earlier, which would set fuel efficiency standards, greenhouse gas standards for cars and trucks. And you've got to think about the power plant standards that the agency announced it's going to move forward on. So if you put all that together, you've got the major pillars of the US commitment to reduce emissions that the President has made going into the Glasgow meetings, which is a commitment to get to 50 to 52%, below 2005 levels by 2030, and net zero by 2050. I think it's fair to say the methane component of that is very significant.

CURWOOD: By the way, Professor, can you put the domestic methane plans of Mr. Biden in the context of what a number of countries, in fact, I think it's close to 100 countries around the world, are now pledging to do about methane?

FREEMAN: Yeah, the domestic policy that the EPA just announced is really our part of a global climate pledge to reduce methane. So what the Biden team did was decide to back a global methane commitment. And that commitment is to cut 30% of methane emissions by 2030 compared to 2020 levels, and try to sign up as many countries as possible to that global methane pledge. And so far, over 100 have signed up.

CURWOOD: 100 plus countries have signed on, but some of the biggest sources -- I'm thinking India, I'm thinking China, I'm thinking Russia -- haven't signed on. How effective do you think that international methane pledge is going to turn out to be?

FREEMAN: Well, what I'd say is, I think they have at least half and maybe more than half of the largest emitters signed up to the pledge. I'd say, though, that this process isn't over; even overnight, more countries joined it. So I think you'll see progress. I think you'll see a lot of pressure in bilateral meetings and in other international fora to add members to the pledge and a lot of pressure will be put, eventually, on countries like China and others who haven't joined. But I think the framework is a crucial first step. So it's a very important global commitment, because as I said, even though methane is a relatively small share of global emissions, it's a very powerful climate forcer.

U.S. President Biden, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, and other world leaders at a high-level session at COP26 in Glasgow, Sweden. The U.S. and the U.K. were among more than 100 countries to sign on to the Global Methane Pledge at the climate talks. (Photo: Andrew Parsons / No 10 Downing Street, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: And it happens over the short term --

FREEMAN: And it happens over the short term.

CURWOOD: I mean, we're seeing the storms, we're seeing the floods, we're feeling the droughts and the fires now, and this is a way that might have a faster impact.

FREEMAN: Yes, almost immediate impact, scientists say. So I think it's a really significant rule proposal that EPA came out with this week. And it has a number of features that are really impressive, and shows that the administration is leaning into this. First thing is it doesn't just set standards for new oil wells coming on, but for all of the existing wells, and we've got about 900,000 wells in this country. So this is a very significant policy in terms of scope of coverage: new and existing sources. The other thing it does is that it requires more frequent monitoring. And you know, you can only fix leaks when you detect them. And you can only detect them when you monitor. So more frequent monitoring is really critical. And the rules EPA already has in place say, if you detect a leak, you must repair. So more frequent monitoring is important. The other thing that policy does is it would eliminate venting, that's just allowing the methane to go up in the atmosphere without being burned first, which reduces its global warming potential. And the final thing to mention is that the rule seeks to stimulate advanced technology adoption. This is really important, because like I say, you've got to detect methane first. It's odorless, right? You can't see it, you can't smell it. So you have to figure out when it's leaking from these facilities. And the way to do that now is to take advantage of these really interesting technology. You can use drones, you can use advanced sensors, you can use satellites; all these things are relatively new, and they work, and they can be lower cost. That's going to make all the difference. And the rule sets up an alternative pathway for companies to deploy those new technologies.

CURWOOD: Now, Jody Freeman, we're talking to you because you're a professor of law at Harvard Law School, which leads me to this question. Regulations like this, big deal regulations like this -- which, I imagine there are portions of industry aren't thrilled by this, it's going to cost them money to implement -- are difficult to promulgate and difficult to keep going in the face of the ability of various folks to contest them in the courts. How strong is this regulation from the legal perspective, in your view? And what sort of gauntlet does it have to run in the legal system to be sure that it in fact endures and becomes effective?

Jody Freeman is the Archibald Cox Professor of Law and the founding director of the Harvard Law School Environmental & Energy Law Program. (Photo: Harvard Law School)

FREEMAN: You're right: most of these major rules, especially the climate rules, get litigated, they get challenged, and the courts are not always friendly to these standards, to say the least. And the Supreme Court at the moment is probably quite unfriendly in its posture, when it comes to agencies doing big things. And the good news about this rule is, it's on a really strong legal foundation. EPA's legal authority is crystal clear. They have a really strong technical record and economic record to support what they've done. There's also the fringe benefit that in this Biden administration, Congress passed a resolution disapproving the Trump rollback of the methane standards, which means Congress has spoken, and EPA actually can't set deregulatory standards. So the legal foundation with Congress having spoken like that is even extra robust.

CURWOOD: Jody Freeman is the Archibald Cox Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

FREEMAN: My pleasure. Great to be with you, Steve.

Links

Learn more about the EPA’s proposed new methane regulations

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth