November 5, 2021

Air Date: November 5, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Troubled COP26

View the page for this story

As the UN climate negotiations among nearly 200 nations called COP26 continue in Glasgow, Scotland, all eyes are on world leaders and negotiators as they face strong headwinds in their efforts to ramp up ambition and commit to substantial climate finance. Alden Meyer is a Senior Associate at E3G and joined Host Steve Curwood from Glasgow to talk about the challenges that remain on important matters like loss and damage, and what it would take for the conference to have a successful outcome. (14:21)

Reining in Methane

View the page for this story

The U.S. oil and gas industry leaks millions of tons of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere every year. New Environmental Protection Agency rules propose to strengthen requirements for industry to prevent, identify, and repair methane leaks, as science says methane emission reductions will quickly help put the brakes on planetary warming. Harvard Law Professor Jody Freeman joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the rules and why tackling methane emissions can make an immediate difference. (09:53)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week, Host Bobby Bascomb talks with Peter Dykstra, an editor at Environmental Health News, about the public health hazards of cement kilns burning plastic waste as a source of fuel. And in California, Scripps Institution of Oceanography is building a 32,000-gallon simulated ocean to study the effects of climate change. Also, a trip back in time to November 1492 when native peoples introduced Christopher Columbus and his expedition to maize, which became a major food staple across the globe. (04:29)

Guardians of the Trees

View the page for this story

Indonesian Borneo is home to Gunung Palung National Park, which hosts diverse species found nowhere else and is beloved by the people who live on the island. But like many people who live near tropical forests, they have at times had to resort to illegal logging to pay for healthcare. To combat this, physician Kinari Webb founded the nonprofit Health in Harmony, which aims to keep the forest healthy by keeping people healthy. Dr. Webb writes about this in her memoir Guardians of the Trees: A Journey of Hope Through Healing the Planet, which she spoke about with Hosts Steve Curwood and Bobby Bascomb at a Living on Earth Book Club event. (18:38)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

211105 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jody Freeman, Alden Meyer, Kinari Webb

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra,

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

COP26 UN Climate talks are off to a bumpy start in Glasgow, Scotland.

MEYER: This process is basically a mirror that we hold up to ourselves to say how well we are doing as a planet in coping with this crisis. The fault is not in the process, the fault is really the absence of political will in too many countries around the world.

CURWOOD: Also, the US plan to tackle climate change by reducing methane emissions.

FREEMAN: Methane is responsible for about 30% of the global warming we’re experiencing and unlike carbon dioxide, its warming power doesn’t come from a gradual build up over time. It’s almost entirely from recent emissions so by reducing methane now it has almost an immediate beneficial impact.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Troubled COP26

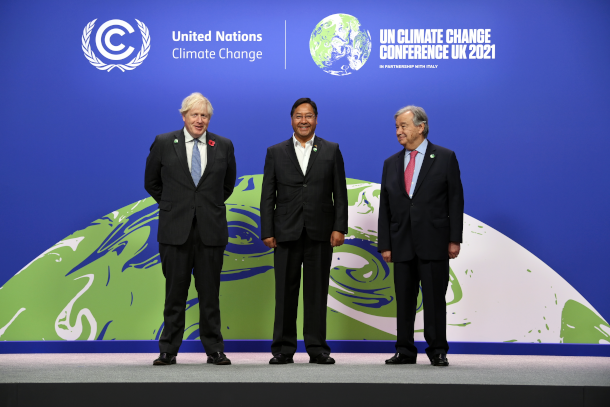

Prime Minister Boris Johnson, Luis Arce, President of Bolivia and Antonio Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations. During the opening of the COP26 world leader summit, the Bolivian President criticized the imbalance of power between developed and developing nations. He said "Developed countries are promoting a new world re-colonization process that we can call the New Carbon Colonialism, because they are trying to impose their own rules in the climate negotiations." (Photo by Karwai Tang, UK Government (Flickr, CC BY NC ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Negotiations are continuing in Glasgow, Scotland through the second week of November at the UN Climate Change Conference, COP26, and so far they are not going well. Under the Paris Climate Agreement of 2015 the nations of the world were due to report their individual national plans that together would cut emissions enough to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees centigrade above preindustrial temperatures. But so far submitted plans would still permit 2.7 degrees Celsius or nearly five degrees fahrenheit of warming, which scientists tell us would all but destroy human civilization as we know it. More than a hundred national leaders representing the US, much of Europe and the Global South attended the opening session, but the leaders of China, Japan, Russia, Brazil and Mexico were among those who stayed home. UK Prime minister Boris Johnson, host of this year’s climate talks, begged the nations of the world to come together.

JOHNSON: It's one minute to midnight on that doomsday clock, and we need to act now. If we don't get serious about climate change today, it will be too late for our children to do so tomorrow.

CURWOOD: Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley called out the missing heads of state and government.

MOTTLEY: Do some leaders in this world believe that they can survive and thrive on their own? Have they not learned from the pandemic? Can there be peace and prosperity, if 1/3rd of the world literally, prospers. And the other two thirds of the world, live under siege and face calamitous threats to our well being.

CURWOOD: Absent action by Congress President Joe Biden outlined executive actions to address US emissions, emphasizing rules he has proposed to slash potent methane emissions. We’ll have more on that later in the broadcast but first for a look ahead to the rest of COP26 I’m joined now by Alden Meyer. He’s a senior associate of E3G, currently in Glasgow Scotland Welcome back to the program, Alden!

MEYER: Thanks, Steve, it's good to be with you.

CURWOOD: So Alden what needs to happen next week, what would make the second week of COP26 successful in your view?

COP26 Logo (Photo: UK Government, Wikimedia Commons)

MEYER: What would register as a real success here in Glasgow would be to have a ambition accelerator package in the final decision, which acknowledge the fact that we're way off track between where we need to be in 2030 to keep any chance of staying below 1.5 degrees Celsius alive, and where we are heading now, and a call to all countries to increase the ambition of their current commitments under the Paris Agreement significantly, within the next year or two, that would be really moving the needle and creating some hope that we're going to come out of this conference with a chance of limiting temperatures to the point where we avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

CURWOOD: Let me ask you about the question of loss and damage, much of the global south has endured a lot of the damage from the effects of climate disruption. And of course, they really don't have the money to deal with it.

MEYER: That's right, and loss and damage refers to the now unavoidable climate impacts that we're starting to see around the world, the floods, the hurricanes and typhoons that are stronger than been experienced the wildfires, the droughts. And the science tells us that even if we were able to zero emissions overnight, and wave a magic wand to do that, those impacts will continue to mount over the next several decades because of historical emissions and inertia in the climate system. So this is an issue that countries are going to really need to start grappling with in a serious way. And we're hoping they're going to start here. The trick, of course, is that what's involved is not billions of dollars, or even tens of billions of dollars, it's literally hundreds of billions of dollars needed today to help these countries deal with the climate disasters, the economic losses that they're experiencing. And it will probably go to trillions of dollars later in the century. So it's a moral issue, i’s an economic survival issue. For many of these countries, it's actually a security issue, as our Pentagon and other security officials in the US have recognized because not helping these countries deal with these problems means mass migration, it means failed states, that means breeding grounds for terrorism. This is not a world that we would want to leave to our children and grandchildren. So dealing with loss and damage is critical. But it's also very difficult. Because countries like Europe, Japan, the United States that put out most of the emissions over the last century century and a half, that have led to this problem don't want to be held liable and feel like they have to compensate for those past emissions. So this is a very polarized issue. It's almost brought down two or three of the Conference of the Parties meetings over the last decade. Hopefully, it's going to be a more constructive tone here. And we'll actually start to give some hope to these vulnerable countries and communities that help us on the way.

CURWOOD: Explain to me the arguments of the countries that historically had the most emissions not being responsive to the question of loss and damage. What do they say is the reason to oppose taking action along loss and damage?

At least 23 countries have today made new commitments to phase out coal power.

— UN Climate Change (@UNFCCC) November 4, 2021

These countries include five of the world’s top 20 coal power-using countries.

Burning coal is the single biggest cause of climate change.

????https://t.co/P3KAC4gRxb | #COP26 pic.twitter.com/aYtGzR7Gep

MEYER: Well yeah, they say that it's only recently that we became fully aware of the impacts of those past emissions. And so one argument is it's sort of fine to hold us accountable in the North for emissions since 1990, for example, when we started negotiating the Rio climate treaty, but we shouldn't be held responsible for emissions over the previous century, century and a half. Others say yes, it is a responsibility, and we need to help. But it's not a legal responsibility. In other words, there's no liability on the table. Of course, some countries in the developing world argue just the opposite, that you are imposing these damages on us by your reckless behavior, and you should be held liable and pay compensation. So that's why I said this is a very charged debate. And we will see where the United Kingdom Presidency of this process is able to get us by the end of next week to try to start to address it in a constructive way.

CURWOOD: Going back to 2009, the climate talks in Copenhagen, didn't go very well. But out of that process, came a pledge from the rich nations to provide $100 billion dollars a year to less wealthy nations, starting in the year 2020 on an annual basis to help them adapt to climate change and mitigate more rises in temperatures. But so far, that hasn't happened, what went wrong and how will this process move forward in your view?

MEYER: Well, that pledge was made in Copenhagen. It was reiterated in Paris and made applicable to the years 2020 to 2025. So it's actually a six year commitment to mobilize public and private resources at that 100 billion dollar level. Why haven't we achieved that? Several reasons: first of all countries, including the United States did not put adequate public resources on the table. Second, those public resources did not leverage the volume of private resources that originally was thought would happen. And third, the World Bank and the other multilateral development bank's have not done what they need to do in devoting more of their financial firepower to addressing the climate crisis to helping developing countries decarbonize their development paths to helping the vulnerable countries deal with climate impact. So it's a combination of three or four different factors coming into this meeting in Glasgow, the United Kingdom presidency asked ministers from Germany and Japan, to consult with the developed countries and to put forward what they call the delivery plan for how those countries intend to meet the commitment. They did submit that a couple of weeks ago, it shows that they expect the 100 billion dollar level will be met in 2023. And it will be exceeded in 2024, and 2025. But of course, over that six year period, they will not meet the 600 billion cumulative target that they committed to and in Paris. So that has been a big topic of discussion here, how to make up some of that shortfall. What to do about the fact that only about 25% of that money is being devoted to climate impacts and adaptation, as opposed to the 50% fifty, fifty split, that many developing countries and international NGOs are are talking about. But of course, the 100 billion is just a prelude the discussion about the much larger sums, hundreds of billions or trillions that need to be mobilized to really decarbonize development in countries like India, Indonesia, South Africa and elsewhere.

CURWOOD: We've seen over this last year, incredible volatility in fossil fuel prices, whether it's the price of gasoline in the United States, or natural gas in the UK, or the price of coal for places like China that buy from overseas. Prices have just gone in some cases through the roof. All of those economies would do better with stable pricing under renewable resources, you know, you can't throw a meter on the sun and double the price. So what is it that's keeping folks from moving forward to the economic stability that a more sustainable and climate friendly set of economies would give us as opposed to the current struggles that we have with the fossil fuel economy?

Kenya President, Uhuru Kenyatta called on leaders of wealthier nations to provide support for Africa and the overall global south. Amongst the environmental issues Kenya faces are deforestation, water shortage, poaching and soil erosion. (Photo: Karwai Tang, UK Government, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MEYER: Well, you're right Steve, that no one puts a meter on the sun, no one charges you for the wind that's blowing. The trick of course, is many of these technologies have a higher upfront capital cost for investment. The good news is that over the last decade solar photovoltaics, LED light bulbs, lithium ion batteries, a whole host of technologies have fallen in cost by 90% or more to the extent where if you're comparing a clean energy package of renewable energy, energy efficiency, investments, storage technologies to a new central coal power station the clean package wins. But of course, we're still depending on fossil fuels for roughly 80% or more of our energy supply. So we're very vulnerable to these erratic price swings on natural gas, coal and oil. But as you say, the economics the national security, the independence from relying on stable imports, all would be addressed if we could accelerate that transition away from fossil fuels and towards these more stable sources.

CURWOOD: You know, I don't think the fossil fuel industry likes the idea of going out of business and perhaps not being able to make the profits that they've made historically.

MEYER: Yeah, they certainly don't and and over the history of this process as we've discussed in the past, they have put up ferocious resistance to every stage of this process. To the original Rio Treaty, where they worked with Saudi and Kuwaiti government officials to try to block adoption of the original treaty to the Kyoto Protocol where Exxon Mobil famously was telling China, India and other developing countries not to accept any binding commitments because it would hurt their economies, and then running multimillion dollar advertising campaigns in the US, saying that the US shouldn't ratify Kyoto because China, India and other developing countries weren't part of it. Totally cynical, but it worked. Now, some of them are starting to realize they have to reinvent themselves. They're seeing the direction of travel, especially in Europe, and realizing if they are going to stay in business unprofitable, they're going to have to move to diversify their portfolio. Some of them are doing that more willingly and gracefully than others. The European carbon majors are out ahead of the US. But none of them have really laid out a pathway to net zero emissions not only in just their operations, but in the products they sell.

The science is clear: We have only a brief window to raise our ambition and rise to meet the threat of climate change. We can do it if the world comes together with determination and ambition.

— President Biden (@POTUS) November 1, 2021

That’s what COP26 is about — and that’s the case I made today in Glasgow. pic.twitter.com/bTcky5oBsP

CURWOOD: Alden, as the climate emergency proceeds, what is the risk to this climate negotiation process that many people will see it as irrelevant to being unable to really fully address the crisis?

MEYER: Well, I think that is a growing concern. There's a widening gap between what this process is delivering and what the public needs and expect from their leaders. And that was pointed out by a number of, of leaders and others. The Queen of England actually talked to the leaders at the reception on Monday night and she said, It's time for you to rise above short term politics and rise to statesmanship that you're doing this not for yourself, but for your children, your children's children, and those that will come after. She was appealing to their better angels and saying get out of your usual food fighting and blame casting and finger pointing and act as if the planet really was at stake because in fact, it is. That is not something that leaders are accustomed to in our current geopolitical world. They're accustomed to maneuvering for advantage. They're accustomed to competing with each other, to trying to frustrate each other's plans. But this is really like an alien invasion. Would this be something that can unite the world to really address this climate emergency in a credible way. If they don't start to do that and signal that they've really moved to that level of urgency and ambition by the end of next week, I think people are going to have growing doubts about this process. But as I've said to you many times, Steve, this process is not to blame. It's basically a mirror that we hold up to ourselves to say how well are we doing as a planet in coping with this crisis, and the real problem is not at these annual conference of the party meetings. It's back in the capitals in Beijing and Delhi and Washington and Brussels, and Pretoria and elsewhere, where there's not enough being done before countries arrive here to move the needle on climate commitments on climate finance on helping deal with loss and damage. So the fault is not in the process, the fault is really in the absence of political will in too many countries around the world.

CURWOOD: Well, I want to thank you so much for taking the time with us today Alden. Alden Meyer is a Senior Associate of E3G and he joined us from Glasgow. Thanks so much Alden.

MEYER: Thanks Steve. I enjoyed the conversation.

Related links:

- Watch live full coverage of COP26 from SkyNews

- Learn more about Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)

- Nature | “The broken $100 Billion Promise of Climate Finance and How to Fix It”

- World Resources Institute | “What Vulnerable Countries Need from the COP26 Climate Summit”

- Inside Climate News | “World Leaders Failed to Bend the Emissions Curve for 30 Years. Some Climate Experts Say Bottom-Up Change May Work Better”

[MUSIC: Eugene Friesen, “Still Life With Moose” on In the Shade Of Angels, by Eugene Friesen, Fiddle Talk Music]

BASCOMB: Coming up – details of President Biden’s plans to cut emissions of the powerful greenhouse gas, methane. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you!

That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: David Cheven and Warren Byrd, “Let Us Break Bread Together” on Let Us Break Bread Together, traditional African-American, CD Baby]

Reining in Methane

Gas flares such as the above burn off methane gas, converting it into carbon dioxide, before releasing it into the atmosphere. CO2 and methane (CH4) are both greenhouse gases, but methane is roughly 80 times more potent over the near term. (Photo: WildEarth Guardians, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood

When it comes to global warming, methane is like CO2 on steroids. Over time methane decays to CO2 but when it is first released into the air methane is about 80 times more powerful than plain carbon dioxide. Methane of course is the principal active ingredient in natural gas, and hydraulic fracturing releases a lot of methane that is captured and sold. But there are a lot of leaks from the natural gas pipe systems and oil wells and coal mines also release a lot of methane that is not captured. These so-called fugitive methane emissions add up to close to a third of the climate forcing that is raising temperatures right now around the world. Without any major federal climate legislation so far in the United States President Biden went to Glasgow to say the US is adopting stringent rules and joining with other countries to fight climate disruption from super-warming methane.

BIDEN: Together with the European Union, we're launching a global methane pledge to collectively reduce methane emissions, one of the most potent greenhouse gases, by at least 30% by the end of the decade. It's the simple, most effective strategy, we have to slow global warming in the near term.

CURWOOD: The White House has issued plans to reduce methane from landfills and food production, but the biggest move so far is an EPA regulation now in the works that would require oil and gas producers to capture methane. They say the EPA rule alone could reduce methane emissions by about 41 million tons through 2035, which would have the climate benefits of taking 200 million cars off the roads for a year. Joining us now is Harvard Law professor Jody Freeman who served as Counselor for Energy and Climate Change in the Obama White House. Jody, welcome back to Living on Earth!

FREEMAN: Great to be with you, Steve.

CURWOOD: Give us a primer about why methane matters so much, right now.

FREEMAN: Well, it's a big deal, because methane is responsible for about 30% of the global warming we're experiencing. And cutting methane is the single fastest, most effective opportunity to reduce climate change risks in the near term. Unlike carbon dioxide, its warming power doesn't come from a gradual build up over time. It's almost entirely from recent emissions. So by reducing methane, now, we can reduce warming that would happen in the near term; it has almost an immediate beneficial impact.

CURWOOD: So interestingly, Jody, the United States has never actually legislated climate change in a big way. We've never really had the laws out of Congress to do this. So it's been up to executive action to address climate disruption so far. So how significant is this announcement from the Biden administration about rules to address domestic methane emissions?

FREEMAN: Well, you're right, Steve, Congress has never passed a comprehensive climate bill. And the Obama team tried to get that done, got it through the House, but didn't get it through the Senate; Biden tried to get a big plan to reduce carbon from electricity through the Congress, doesn't look like that'll pass. And if you remember, back in the day in the Clinton administration, he tried to adopt a BTU tax, which would have reduced emissions too and that went down to spectacular defeat. So in that historical context, what presidents have to use is their executive power. And they use the agencies they've got, primarily the EPA, which implements the Clean Air Act. And it's that authority that EPA used to establish this new methane rule. And it's a really big deal. First of all, it regulates everything in the oil and gas chain: production, processing, transmission and storage. And oil and gas is the largest industrial source of methane emissions. So it's a big target for the agency. And there are really meaningful reductions that they can get. The estimate is that by 2030, this proposal would reduce methane emissions from oil and gas sources by about 75% compared to 2005 levels.

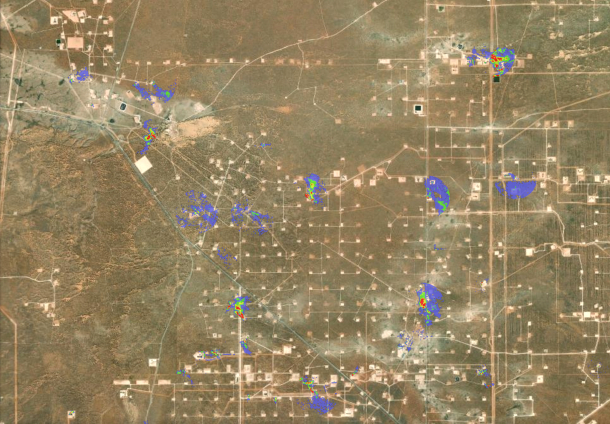

Methane plumes in the New Mexico portion of the Permian Basin oil and gas fields, from remote sensing data gathered during September and October 2019. (Image: Derived from JPL/NASA Methane Source Finder)

CURWOOD: How far would these methane emission reductions get the United States towards its overall commitment in the Paris process?

FREEMAN: Well, it's hard to put an exact number on that. But it's a significant policy that would make real progress, I think we can confidently say. It's hard to get percentages right now, because there's so many proposals that have been made that aren't final. You've got to think about the proposal to cut transportation sector emissions that came out of EPA earlier, which would set fuel efficiency standards, greenhouse gas standards for cars and trucks. And you've got to think about the power plant standards that the agency announced it's going to move forward on. So if you put all that together, you've got the major pillars of the US commitment to reduce emissions that the President has made going into the Glasgow meetings, which is a commitment to get to 50 to 52%, below 2005 levels by 2030, and net zero by 2050. I think it's fair to say the methane component of that is very significant.

CURWOOD: By the way, Professor, can you put the domestic methane plans of Mr. Biden in the context of what a number of countries, in fact, I think it's close to 100 countries around the world, are now pledging to do about methane?

FREEMAN: Yeah, the domestic policy that the EPA just announced is really our part of a global climate pledge to reduce methane. So what the Biden team did was decide to back a global methane commitment. And that commitment is to cut 30% of methane emissions by 2030 compared to 2020 levels, and try to sign up as many countries as possible to that global methane pledge. And so far, over 100 have signed up.

CURWOOD: 100 plus countries have signed on, but some of the biggest sources -- I'm thinking India, I'm thinking China, I'm thinking Russia -- haven't signed on. How effective do you think that international methane pledge is going to turn out to be?

FREEMAN: Well, what I'd say is, I think they have at least half and maybe more than half of the largest emitters signed up to the pledge. I'd say, though, that this process isn't over; even overnight, more countries joined it. So I think you'll see progress. I think you'll see a lot of pressure in bilateral meetings and in other international fora to add members to the pledge and a lot of pressure will be put, eventually, on countries like China and others who haven't joined. But I think the framework is a crucial first step. So it's a very important global commitment, because as I said, even though methane is a relatively small share of global emissions, it's a very powerful climate forcer.

U.S. President Biden, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, and other world leaders at a high-level session at COP26 in Glasgow, Sweden. The U.S. and the U.K. were among more than 100 countries to sign on to the Global Methane Pledge at the climate talks. (Photo: Andrew Parsons / No 10 Downing Street, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: And it happens over the short term --

FREEMAN: And it happens over the short term.

CURWOOD: I mean, we're seeing the storms, we're seeing the floods, we're feeling the droughts and the fires now, and this is a way that might have a faster impact.

FREEMAN: Yes, almost immediate impact, scientists say. So I think it's a really significant rule proposal that EPA came out with this week. And it has a number of features that are really impressive, and shows that the administration is leaning into this. First thing is it doesn't just set standards for new oil wells coming on, but for all of the existing wells, and we've got about 900,000 wells in this country. So this is a very significant policy in terms of scope of coverage: new and existing sources. The other thing it does is that it requires more frequent monitoring. And you know, you can only fix leaks when you detect them. And you can only detect them when you monitor. So more frequent monitoring is really critical. And the rules EPA already has in place say, if you detect a leak, you must repair. So more frequent monitoring is important. The other thing that policy does is it would eliminate venting, that's just allowing the methane to go up in the atmosphere without being burned first, which reduces its global warming potential. And the final thing to mention is that the rule seeks to stimulate advanced technology adoption. This is really important, because like I say, you've got to detect methane first. It's odorless, right? You can't see it, you can't smell it. So you have to figure out when it's leaking from these facilities. And the way to do that now is to take advantage of these really interesting technology. You can use drones, you can use advanced sensors, you can use satellites; all these things are relatively new, and they work, and they can be lower cost. That's going to make all the difference. And the rule sets up an alternative pathway for companies to deploy those new technologies.

CURWOOD: Now, Jody Freeman, we're talking to you because you're a professor of law at Harvard Law School, which leads me to this question. Regulations like this, big deal regulations like this -- which, I imagine there are portions of industry aren't thrilled by this, it's going to cost them money to implement -- are difficult to promulgate and difficult to keep going in the face of the ability of various folks to contest them in the courts. How strong is this regulation from the legal perspective, in your view? And what sort of gauntlet does it have to run in the legal system to be sure that it in fact endures and becomes effective?

Jody Freeman is the Archibald Cox Professor of Law and the founding director of the Harvard Law School Environmental & Energy Law Program. (Photo: Harvard Law School)

FREEMAN: You're right: most of these major rules, especially the climate rules, get litigated, they get challenged, and the courts are not always friendly to these standards, to say the least. And the Supreme Court at the moment is probably quite unfriendly in its posture, when it comes to agencies doing big things. And the good news about this rule is, it's on a really strong legal foundation. EPA's legal authority is crystal clear. They have a really strong technical record and economic record to support what they've done. There's also the fringe benefit that in this Biden administration, Congress passed a resolution disapproving the Trump rollback of the methane standards, which means Congress has spoken, and EPA actually can't set deregulatory standards. So the legal foundation with Congress having spoken like that is even extra robust.

CURWOOD: Jody Freeman is the Archibald Cox Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

FREEMAN: My pleasure. Great to be with you, Steve.

Related links:

- Washington Post | “Biden unveils new rules to curb methane, a potent greenhouse gas, from oil and gas operations”

- Learn more about the EPA’s proposed new methane regulations

- Explore JPL/NASA’s Methane Source Finder map tool

- Read the White House Office of Domestic Climate Policy’s overall U.S. Methane Emissions Reduction Action Plan

- About Jody Freeman

[MUSIC: Vusi Mahlasela, “Loneliness” on The Voice, by Vusi Mahlasela, ATO Records/BMG Music]

Beyond the Headlines

Some cement factories are collecting plastic waste from consumer goods businesses and landfills to use as fuel to fire their kilns, posing the risk of polluting air with toxic chemicals. (Photo: Xopolino on Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: It's time for a trip now Beyond the Headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org, and DailyClimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby. There's an investigative story from Reuters. They've looked into cement kilns, cement kilns are everywhere, especially in booming cities in the developing world. They're responsible for 7% of all the greenhouse gases emitted. So that's a huge chunk. And right now, those cement kilns are looking for a new source of fuel to fire up the kilns and they've hit upon plastic waste. And that can be a bigger problem than any problem they may be solving.

BASCOMB: Hmm. Well, that makes sense. I mean, plastic is made with fossil fuels. So it's, you know, pretty energy rich and there's so much plastic waste out there. It's free, or maybe even in some places might pay to have it, you know, burned like that. But of course, you know, it's not too good for air quality now, is it?

DYKSTRA: Right, and there are consumer firms that are funding projects to send their plastic trash to cement plants. It's a dangerous idea, given the amount of carcinogenic fumes that exists in those plastics, now burning straight, from, in many cases, the developed world to the developing world, to all of our lungs.

Cement factories are burning plastic to fire up massive cement kilns like the one pictured here. (Photo: LinguisticDemographer on Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: Yeah, I mean, looking at things like dioxins, heavy metals, carcinogens. I mean, it's pretty, pretty toxic stuff.

DYKSTRA: And it's been said that burning plastics in cement kilns doesn't help lessen the landfill problem. It simply transfers the landfills from being on the ground to in the skies.

BASCOMB: Well, that certainly is a big problem. Well, what else do you have for us this week Peter?

DYKSTRA: It's kind of a weird sci-fi sort of project. The Scripps Institute out in San Diego is building a 32,000 gallon tank that has a wind tunnel on top of it. And with all that, they hope to synthesize what happens in the ocean, and how the oceans can affect climate change.

BASCOMB: How will they do that?

DYKSTRA: There are wind currents brought in, water currents introduced mechanically into this tank, and we'll see what happens as climate change begins to alter both wind and wave and current patterns. It'll give a little bit more of an insight as to what lies ahead in our future, as climate change really takes hold in our oceans.

The surface layer of the ocean can tell scientists a lot when looking at climate change. That is one aspect researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography will study in their simulated ocean. (Photo: NOAA on Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: So they can simulate climate change in this pool and sort of speculate what we're going to be looking at then.

DYKSTRA: Right, and thanks for using the word pool because 32,000 gallons sounds like a lot, but it's actually about 5% of what it takes to fill in a competition sized Olympic swimming pool.

BASCOMB: So it's really not all that big then. It's amazing what they can do in such a small space.

DYKSTRA: It is. Scientists can have fun with it and can give us some information that’ll help guide us through a particularly dangerous time in our environmental future.

BASCOMB: Indeed, well, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: November 5, 1492. And we all know what happened in 1492. Columbus sailed the ocean blue. And on his subsequent stop to the Bahamas, Columbus went to Cuba in early November, and he was introduced to maize. That corn was brought back to Europe and has since become a global staple for both humans and livestock.

BASCOMB: Well, yeah, there's so much to that. I mean, that the Columbian Exchange brought tomatoes and potatoes to Europe. I mean, imagine Italian food without tomatoes, but before that, they made do I guess.

Maize has become a food staple around the world after it was introduced from the New World to the Old World in 1492. (Photo: Balaram Mahalder on Wikimedia Commons)

DYKSTRA: And even though Columbus was a tip of the spear, coming from Europe, in the genocide of native peoples in the West, one other thing that was a gift so to speak, from North America to Europe was of course, tobacco. So it's feed ya and kill ya, Mr. Columbus.

BASCOMB: All right. Well, thanks Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Bobby. Thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe dot org.

Related links:

- Reuters | “Trash and Burn: Big Brands Stoke Cement Kilns with Plastic Waste as Recycling Falters”

- WIRED | “This Groundbreaking Simulator Generates A Huge Indoor Ocean”

- Read more about the Columbian Exchange

[MUSIC: The RH Factor, “The Scope” on Nothing Serious, Verve Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – To heal the carbon-rich rainforests of Borneo first heal the people who live there. How to do it is ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Osland Saxophone Quartet, “Cityscapes-Lake Shore Drive” on Commission: Impossible, by Rick Hirsch, Sea Breeze Records]

Guardians of the Trees

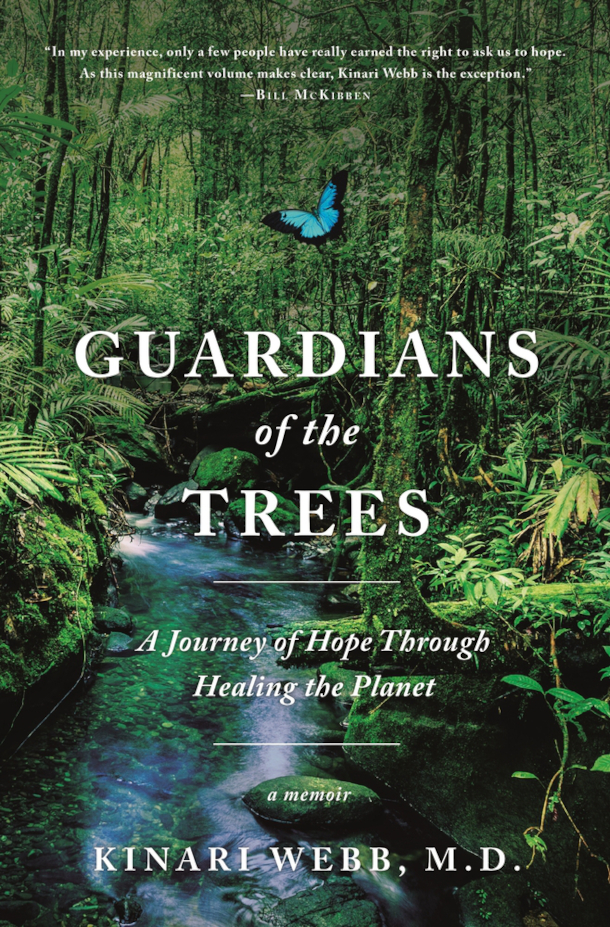

“Guardians of the Trees: A Journey of Hope Through Healing the Planet: A Memoir” reflects on the connections between human health and planetary health through the eyes of physician Kinari Webb as she treats patients in the rainforests of Indonesian Borneo. (Photo: Courtesy of Flatiron Books)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Gunung Palung National Park in Indonesian Borneo is home to hundreds of endemic species found nowhere else on earth; think orangutans, white bearded gibbons, and proboscis monkeys to name a few. And the rainforests of Borneo are vitally important both as a habitat and a sink to absorb and store climate warming carbon dioxide.

Much of the soil in Borneo is peat bogs, one of the most carbon dense ecosystems on earth. Largely because of deforestation Indonesia often ranks in the top 10 for greenhouse gas emitting countries.

CURWOOD: Kinari Webb is a physician who first saw the deforestation in Indonesia when she was still a college student. Deeply troubled she asked the local people what they needed to stop cutting the trees. And when they told her they needed medical care Kinari changed her life. She came home to the US, eventually went to medical school and completed a family practice residency before heading back to the rainforest to listen again to the people there to learn how she could best provide high quality health services. Her memoir, Guardians of the Trees: A Journey of Hope Through Healing the Planet explores her challenges and successes in Borneo. Doctor Webb recently joined Bobby and me for a Living on Earth Book Club live event at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health to tell her story.

WEBB: So when I first went to Borneo to study orangutans, I was just so angry at the local community members who were cutting down these giant rainforest trees, which might even be 1000 years old. And I just thought, how can they do this? Don't they know that the forest is also important for their own future wellbeing, and not just the future wellbeing of the whole planet? But then I got to know many of them and it just broke my heart when I realized what they told me was going on is that they were often forced to log to pay for health care. And that just shouldn't be. And why do these communities have so few resources? Because of many 100 years of colonialism, right? So what I like try to explain to people here in the US often, is your wellbeing is actually dependent on the wellbeing of people living around rainforests. And when they're also forced to invade into forest, you have a higher chance of spillover for pandemics. You know, this is not the only problem for loss. Of course, of course, we also have companies cutting down large amounts of forests. But this problem of local communities wanting to protect the forest and not able to, is a serious problem in many, many places. And it's often access to health care. Right? One woman told me if anyone tells you that they have not logged to pay for health care, they are lying to you, because that is the only way to get enough money for a medical emergency, which can cost an entire year's income.

CURWOOD: So I take it this is your inspiration for starting the group Health In Harmony.

WEBB: Yeah.

CURWOOD: And you say at one point this is a divine calling, this work.

Gunung Palung National Park is the unfortunate target of illegal logging, often by locals who resort such measures to pay for healthcare costs. (Photo: Tom, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

WEBB: Yeah, it is. It is, I'll tell you, this book is also a divine calling. And if I didn't have to do it, I wouldn't, I would much rather not have released this book. But we don't have time. And this is the great period of time, in probably all of human history. We either make this enormous change, where we recognize that we are all interrelated and that we will not survive without each other. And when I use the word all, I mean it in the way that many indigenous communities use it. Whereas our cousins, the trees and the animals, right? We are all interrelated. And we can't survive without our lungs and our heart. And it's like, we can't survive. And we can't survive if some people are suffering, because of a long history of colonialism, resources need to flow back. And these communities know what the solutions are. They know how to solve the problems, how to address the critical, I call them fulcrums of change. These areas where if you change those few things, and I think they're completely invisible to outsiders, but local communities can say if these things change, everything else will change.

BASCOMB; Well, that's certainly true. Can you tell our listeners some of the details of how it works? How do you provide health care to people in exchange for not logging? What were some of the details that you've worked out with them? Or really that they suggested to you?

WEBB: Yeah, so some of the cool things are, they wanted affordable, high quality health care, Okay, so affordable, how do we make it affordable? Well, we could just provide it for free. But then they said if they was free, they wouldn't value it as much. But we want everyone who can, no matter how poor they are to be able to pay for it. So the way that we did it was everyone can pay with non cash payment options, and you can pay with seedlings. And if a given community is not logging at all, they get a greater thanks from the world community. So they get a 70% discount on their health care costs. So they have to pay with fewer seedlings. If their community is logging, they have to pay with a little bit more seedlings. But they love this because they see this direct connection. And it helps them encourage the few folks who are continuing to log to stop. And then they asked for alternative livelihoods in organic farming training. So that's also, you can also in our clinic pay for your health care with manure, we use that manure for the for the organic farming training. So there's always this, you can see very clearly how the health of the natural ecosystem and the health of the economic system is fully related to the health of people. Which is true, right? That's just true. And it tends to be the way that rainforest communities see it, right, this everything is interconnected. But in the West, we tend to be very siloed. We think healthcare is somehow separate from the environment and somehow separate from economic well being. But of course it isn't.

Health in Harmony is part of the nonprofit ASRI founded by Dr. Webb which also has a location on Java Island in Indonesia. Here, ASRI’s Director of Conservation Programs, Dika, stands in a seedling nursery. (Photo: Stephanie Gee)

BASCOMB: That's really profound. And I think you really do have such a wonderful model here for other countries and other communities to emulate. Can you talk about, you know, maybe the personal story of one of the people that came into your clinic that you were able to help? I'm thinking of a patient named Dardi. Can you tell his story for us?

WEBB: Sometimes I think about his story as a metaphor for where we all are on the planet. Dardi, his mother found us at an eyeglass distribution center, when we were giving out eyeglasses one day, and she must have run long distance to come and find us. And she's "please, please come see my son". So we went to go see her son, she has a tiny little house very, very small. And within that space, she had created this sort of even tinier little room that was completely dark. And he had been in that dark room for eight years, suffering in horrible, excruciating pain in his head. He was also incontinent, although his mother kept him exquisitely clean. And he couldn't tolerate any noise, he couldn't tolerate any light. And it turned out that he had tuberculosis of his brain. And probably had like a tuberculoma, which is a kind of a massive tuberculosis in his brain. So he was in just terrible distress, suffering extremely. She had spent every bit of money they possibly had on care and had not been able to figure out what was wrong with him. We were able to correctly diagnose him and start him on treatment. He was, in fact, our first inpatient at the clinic when we started. And that was like, it was kind of a, this totally miraculous thing. We had to like, bring him at night, and like, you know, put all shades, nearly carry him into the clinic. And then we were able to give him antibiotics, that tuberculosis medicines and also some steroids to kind of prevent any, as all the TB bacteria are dying, they can create a lot of inflammation. So we were able to treat him. Within two days, he is like, like walking, he can tolerate light. I mean, it was, just the improvement was just unbelievably dramatic. And his mother paid with non-cash payments, she went paid with these beautiful handicrafts that she had made. But the thing about TB medicines, you have to take them for a very long time. Because even though you have this dramatic improvement right away, you really have to take your medicines. So that was a whole nother process. But then, even though he eventually was better, physically, he was terrified. He was terrified to go outside, after being in the dark for so long. You know, it makes sense that you would just be scared, right? It's a totally new thing out there. And so then we had to have a psychiatrist come and work with our Indonesian docs to teach them how to help him, slowly learn how to be in the world. And that did work. And then one day, he actually asked Dr. Made, who was the doctor is taking care of him, can I go to the beach. And for me, that is kind of like, that's where we are on this planet, right? We have been in the dark for a very long time. We are just beginning to see our interconnections. We are just beginning to see what a massive crisis climate change is. But now we're scared. Even though the truth, the healing knowledge of truth is basically here from almost all of us. We don't know what to do. We don't know how to be in the world. And there is that personal healing and that community healing that leads to the planetary healing. And eventually Dardi actually got a job and he was able to support his family. And, you know, he had this integrated health in all ways, with a healthy sustainable livelihood, and a sustainable family, and he could have access to continued care. That's what we need to do on our planet. We need to do the personal healing, and the community healing and the global healing. And we need to listen to those who have suffered the most about what the solutions are.

A patient is treated at the ASRI medical clinic. (Photo: Stephanie Gee)

BASCOMB: It seems a tall order, but you've really given us a path forward, I think, with this book and the beautiful stories within it.

WEBB: We're also working on a platform to really help people connect around the world, where people can see the solutions of rainforest communities and then be able to partner with them. And yeah, bring about this great healing.

BASCOMB: Before you really got going with your clinic and the reforestation efforts there, you engaged in something you called radical listening. You know, the notion that you want the members of the community, you want to go and ask them what they need and then listen to them. And that was sort of a radical approach to this type of work. Can you tell us a little bit about why is that a radical notion? Why isn't that done more often?

WEBB: Yeah, well, you wouldn't think it'd be radical, right? I mean, I always kind of joke like, like, the really radical thing is that we don't only listen to communities about the solutions are, we actually do it, right? Because lots of organizations say they listen, or they get input about what their idea is. That's, that's a common way of doing it as well, which from my perspective, is not radical listening. Radical listening is to let go of your own control of what the answer is. To say, I trust you, I trust the local knowledge that you know what the best solutions are. And then I will absolutely bring resources from the global north, and exactly execute your solutions. It's radical also, because it is a reversal of the colonial flow of resources. And it's not just like one and done. It's a constant process of like working with the communities. Okay. So how's this going? Now, do we want adjusted in any way? And how that's going? And what is, and it's not just like the biggest part of the solutions, but every detail of the solutions as well.

CURWOOD: So I want to follow up with a question because, I mean, you've had such remarkable results in Borneo. And the question is, how might these be replicated in other forest communities, the Amazon or the Congo and wanted to know, particularly about your experience in the Brazilian part of the Amazon, especially during this pandemic?

A young girl plants a seedling at the ASRI clinic in Gunung Palung National Park in Indonesian Borneo. (Photo: Chelsea Call)

WEBB: Yeah. So we have known we needed to move really fast. And we knew we had a model which looked like it was working in Borneo. It was very, Stanford did an evaluation, it looked very, very successful. The data is excellent. But we wanted to see if it would work in ecosystems that were very different. So we started working in Madagascar. Actually, Emerson, who's our fabulous program director, she says, if we can be successful in Madagascar, we were very successful anywhere in the world, because there are so many stressors, and it's very, very difficult to work there. But we have so far been wildly successful. And again, with radical listening, the communities are identifying healthcare, alternative livelihoods and education access as the key factors. And again, in Madagascar, the threat to the forest is primarily individuals who want to protect the forest, but just don't have a choice. And see that they are making a choice between their short term well being and their long term well being. But what are you going to do, right? I mean, if I had to cut down trees to pay for a C section, I would do it, right? Of course I would. It's a little different in the Amazon, what you have are rainforest communities, indigenous communities, other traditional communities, like descendants of rubber tappers, who are living in the forest and protecting it and protecting it from invaders. But when they get sick, and die, or when they have to leave to access services, they leave forest vulnerable to be invaded by outsiders, to be cut down. And occasionally they will make deals. There's one man we know of who had worked his entire life to protect the forest. And then his son got really sick and was going to need long term care. And he made a deal with a logging company who came in, right and they paid him enough that it would be, he would be able to take care of his son, and how can you blame him? And yet, I don't want anyone to ever have to make that decision. So we did radical listening again with these rainforest communities and asked them what they would need. What are the solutions that they see for protecting the forest? What do they need, we call it a thank you from the world community, so that they can protect this forest? And again, they needed access to health care, particularly during the pandemic. They needed the ability to be evacuated, if they were very sick. They needed vaccines. So we've been doing vaccine trips up, and they needed health care trips, like three or four times a year. And we've been doing that as well.

CURWOOD: How do you bring what you've learned with radical listening home to America? Because we have a society where instead of cutting down trees, people are burning or extracting fossil fuels, investing their retirement accounts in fossil fuels. So, how do you bring this concept of radical listening back to an America that is so broken right now seems like we don't listen to each other. We have nurses picketing hospitals protesting a vaccine mandate. I mean, man, it seems to me the folks in the rainforest are in a much better shape than we are right now.

Kinari Webb MD is the founder of nonprofit Health in Harmony and the author of Guardians of the Trees: A Journey of Hope Through Healing the Planet: A Memoir. (Photo: Courtesy of Flatiron Books)

WEBB: Well, I think actually, many of the issues are very similar. First of all, there are social justice issues. Right? There's intersectional environmentalism, which is to say, where are the worst polluting industries? In communities of color, right? What are the solutions? Those who are closest to the problems are going to know the solutions the best. And I believe that should be on a neighborhood basis, which is to say every neighborhood is going to know what the solutions are for their neighborhood. And the way we do radical listening is people sit in a circle, everyone would know, what would you need as a thank you from the world community so that you could actually reduce your fossil fuel emissions? Right? I highly suspect that access to health care is actually one of those key fulcrums of change also, in this country. That if we had universal health care, I know many people would change their jobs, would choose livelihoods that were actually about thriving, right, thriving personally and thriving globally. But they often don't feel like they can even leave the jobs that they have because of access to health care. I don't know what the solutions would be. But I know who to ask. Right? And I know that communities could come up with solutions. And even imagine if we got discounts on our health care premiums, if we were emitting, you know, less fossil fuels, right, like, they should be connected, they are connected. So why not directly connect them? I bet it would work wonders.

CURWOOD: Dr. Kinari Webb is the founder of Health In Harmony and the author of Guardians of the Trees: A Journey of Hope Through Healing the Planet. And just say, Kinari, thanks so much for for joining us.

BASCOMB: Thank you so much, and best of luck in the rest of the work that you're doing there.

WEBB: Thank you so much. It's such an honor.

Related links:

- Learn more about Kinari’s nonprofit, Health in Harmony

- Find the book "Guardians of the Trees" (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- More about “Guardians of the Trees” on the MacMillan website

- Watch the full recording of this Living on Earth Book Club live event

[MUSIC: Lotus, “The Monkey And The Moon” on Borneo]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Genevieve Santilli, Teresa Shi, Gabriell Urton, and Jolanda Omari. We say a fond farewell to Jay Feinstein who did so many things for us, including launching the LOE book club.

BASCOMB: Best of luck Jay. We’ll miss you. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb. And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth