Tropical Forest Riches

Air Date: Week of November 12, 2021

A tropical rainforest in the Danum Valley Conservation Area, Malaysia on the island of Borneo. (Photo: Jeremy Bezanger on Unsplash)

Tropical forests are a treasure trove of biodiversity and contain vast stores of carbon that threaten the stability of Earth’s climate system if released through deforestation. Max Holmes, acting President and Executive Director of the Woodwell Climate Research Center, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the threats to tropical forests and explain the importance of protecting them from further degradation.

Transcript

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

One of the biggest promises made at COP26 alongside the main negotiations were pledges from more than 130 countries to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by the year 2030. More on that later in the show, but first let’s talk about why tropical forests are such an important part of flattening the carbon emissions curve. With me now is Max Holmes, he’s acting President and Executive Director of the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Falmouth, Massachusetts. Welcome to Living on Earth, Max!

HOLMES: Thanks, Steve. It's great to be here.

CURWOOD: It's our pleasure. So, tell me, why are tropical forests in particular so important to the carbon cycle?

HOLMES: In short, because tropical forests hold a vast amount of carbon in them. And the concern is that if the trees are cut down, if they burn, if human activities otherwise get rid of those, those trees, that carbon that's been locked up in the trees for decades and centuries, in many cases, goes to the atmosphere and leads to more warming. A few numbers that help put this in context: first, I'll just start with the amount of carbon that's in the atmosphere right now -- carbon is carbon dioxide. So, this is about 850 billion tons of carbon in the atmosphere, currently. All the forests on Earth contain about 500 billion tons of carbon, that's carbon in the vegetation, so in the trees, the stuff that you see above ground, as well as the roots below ground, so around 500 billion tons in trees. Tropical forests have about 300 billion tons, so something like 60% of the global forest carbon is in tropical forests, so a really big number. And so, you can see how losing carbon from tropical forests can have a big impact on how much carbon is in the atmosphere, and thus how much the earth warms.

CURWOOD: And by the way, how much do humans put into the atmosphere every year at this point?

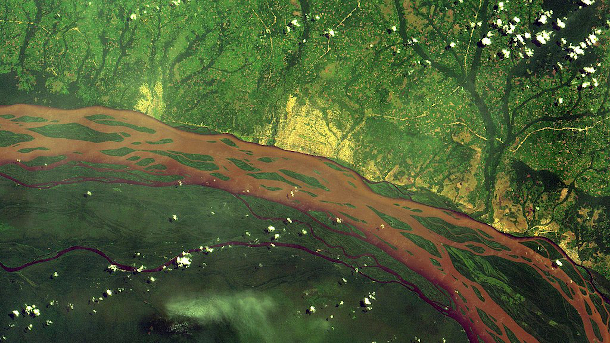

Deforestation from July 4, 2000 - July 16, 2019 around BR-163, a highway in the northern Brazilian state of Pará that links soy-growing areas with an ocean-going port on the Amazon River. (Photo: Lauren Dauphin, NASA Earth Observatory, public domain)

HOLMES: Human activities right now are putting something around eleven, eleven and a half billion tons per year into the atmosphere -- around ten billion tons from fossil fuel combustion, so that's oil, gas and coal that we're using, and around a billion or a billion and a half tons from land use change from, from deforestation.

CURWOOD: So crude mathematics would say if you do that for the last 30 years, since we've been talking about the climate agreement, we're getting up there at least a couple of hundred, maybe even 300 billion tons of carbon we've put into the atmosphere just since we started talking at the UN.

HOLMES: Yeah, that's right, we have put a lot of carbon into the atmosphere since we started talking about this problem, recognizing the problem. And that just means that we have to work a lot harder now. It's getting a lot more difficult and a lot more expensive to reverse course now. But that also just makes it a lot more urgent that we get to work on this right away. Of the carbon that we do put into the atmosphere, only about half of it stays there. The other half gets split between the ocean and land. So, the land is sucking carbon out of the atmosphere and the ocean is also absorbing carbon. So, they're both doing us a big favor, helping to pull some of that carbon that we put into the atmosphere back out.

CURWOOD: Max, by the way, where are the main tropical forests in the world? There's the Amazon, of course, but talk to me about the group of them.

HOLMES: Yeah, the largest is the Amazon, the one that we all think about and hear about a lot. The second largest is in the Congo, also just a vast tropical forest. And then the forests of Indonesia are also super important -- not as large, but they're very carbon rich. And they're all under threat. So, there's been some pretty rapid change underway in the Amazon right now, that, that needs to reverse. The Congo, ironically, it is more pristine, it has had less direct human intervention. It doesn't mean that there hasn't been any, but there hasn't been widespread clearing in the Congo for the most part. It's not necessarily that there's been particularly enlightened environmental policy. It's been an unstable region, and because of that, you know, big multinational corporations haven't come in there. It hasn't really been safe for lots of the activities that have led to deforestation in the Amazon, for example. So, it's this situation where, as peace and stability increase, we hope, we certainly hope those things increase in the Congo, that could lead to additional threats to the forests.

CURWOOD: And Indonesia?

HOLMES: Yeah, so some of the big activities happening there that lead to deforestation, so palm oil plantations are a big driver of that; forests are cleared to plant palm trees to create palm oil. A lot of those forests in Indonesia, they're, they're on peatlands, which are very carbon rich areas. So, you get the, let's say, a double whammy when you clear those forests. Not only are you losing the carbon that's in the trees, but there's a lot of carbon locked up in those peatlands soils in some of those areas that you're also -- once they dry out, associated with the clearing of the land, the soils dry out, and that carbon that's been locked up in the peat for a long time can also be released to the atmosphere. So that's contributing a lot of carbon to the atmosphere.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about how the storage of carbon in old growth tropical forests compares to young, regrowing or planted forests there and elsewhere in the world.

A satellite image of the Congo River running through the rainforest in the Democratic Republic of Congo. (Photo: Coordenação-Geral de Observação da Terra/INPE, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

HOLMES: Yeah, so that's an interesting question. And I'm looking out my window right here in Woods Hole, in Falmouth, on Cape Cod, and there are beautiful trees out the window. And, you know, all of those trees started with a little seed, a tiny little seed. And now they're these massive, you know, 100 feet tall, 100 and some feet tall, with loads of carbon in their bodies. And you think about, okay, where did this carbon come from? The carbon in those trees -- and it's mainly carbon, that's, that we're looking at when you're looking at a tree -- that all came out of the atmosphere, the trees pull that carbon out of the atmosphere, that carbon dioxide, and they use that to build themselves, to build the tree. So, you know, sometimes it's argued that, yeah, you can, you know, cut down trees and the forests are going to regrow. This is a renewable resource. On the one hand, that's certainly true. The issue is the timeframe. I like the analogy of a bank account. You can think of a savings account that maybe you started as a kid, and you're, you know, every year or every month, you're putting your allowance into that, and you're putting some money into it, year after year, and over time, you build up some, some amount of money. And it took a long time, a lot of work to build up that bank account, that savings account balance, but you can blow it in a hurry if you go out and buy that thing that you've, you know, that new car or whatever it might be that you're interested in, and you go down to zero. Can you renew that, that amount of money that's in that savings account? Of course, you can, but it's going to, again, take a lot of time to do it. And it's a similar thing with forests. Forests with this vast amount of carbon that they contain, it takes them a long time to build it up. It's not a year, it's not ten years, it's in many cases, not even a hundred years. It's longer than that to build up all that carbon. Just like you can empty out your bank account in a hurry, you can empty the carbon out of a forest in a hurry. You chop those trees down, you burn them, all that carbon goes back to the atmosphere right away. Yeah, you can build it back. But it takes a lot of time. With climate change right now, we don't have that time. We've got to keep the carbon in the forests that are standing; where we can restore forests, we need to start doing it, it will pull carbon out of the atmosphere, but it's gonna, it will take them a long time to restock that balance they'd started with before we deforested.

CURWOOD: Max there's some research that we reported on earlier this year that suggests that parts of the Amazon are so degraded that they're becoming sources of carbon, rather than serving as carbon sinks, that is absorbing it. And then there are even other compounds coming out of the Amazon, such as methane, and nitrogen compounds, that also can, can warm the atmosphere. How close do you think we're at a tipping point where the tropical forests, and the Amazon in particular, is no longer able to function as the lungs of the planet?

Rainforest in Kinabalu Park, Malaysian Borneo (Photo: Dukeabruzzi, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

HOLMES: Yeah, so it's kind of scary news, some of this latest research, and it does seem to show that the Amazon is getting really close to that point where instead of pulling carbon out of the atmosphere on net, it's turning into a source of carbon to the atmosphere. I think some of the latest studies I've seen have suggested that the Brazilian part of the Amazon, which is the biggest chunk of the Amazon, it may already be a small carbon source to the atmosphere. The Amazon, overall, still seems to be a small carbon sink, but we're getting close to that point where it's going to be a net carbon source overall. Now, with respect to, are we going to hit some tipping point, that's certainly a concern. One of the things that, that maintains the forests of the Amazon is precipitation that's generated by the forest. So, trees need a lot of water to survive, they also lose a lot of water through their leaves to the atmosphere. That water that's lost, that water vapor that's lost, can lead to more precipitation. So, water loss from one tree may lead to precipitation that sustains another tree in the Amazon farther downwind. If you lose enough trees, if you do enough deforestation that can impact the amount of rain that falls in the Amazon, it can lessen the amount of rain that falls in the Amazon. And that can cause the forest to die. So, there's concern that, you know, there have been estimates that if you deforest 40% of the Amazon, that might be enough to hit that tipping point where the whole thing just collapses. There are some other studies that suggest it might be 20% -- if you deforest 20%, it might put you over the edge where the forest can't maintain itself. That's within range, so that just means that, given we don't know exactly where that tipping point or threshold is, all the more incentive to slam on the brakes right now, while we can.

CURWOOD: The countries who have pledged to stop deforestation in less than 10 years feel like they're taking pretty good action. But we know what actually happens isn't just up to what the leaders decide or pledge at a conference in Glasgow. What else would you recommend to people listening to this doing? What can people do to help in the situation of the threats to our forests?

HOLMES: Yeah, I mean, it gets back to thinking about the drivers of forest loss, globally and in the tropics. One of the big drivers is just climate change overall. The Earth's climate is changing, it's human activities that are driving those changes, that's leading to forest loss, forest dieback, fires, insect outbreaks, all those things. So, you know, there's the list of individual activities, community activities, family activities, business activities we can all do to help put the brakes on climate change. Another of the big drivers of deforestation in the tropics, in the Amazon, is agriculture, right? So, they're clearing forests to grow soy. Why are they growing soy? The soy is not to feed us. There's, yeah, okay, we eat some soy. But it's not primarily to make tofu or something like that that we're eating, it's to feed animals that we're eating. And that is a very big driver of deforestation in the Amazon. So, what can we do as individuals? We can think about what we're eating, we can eat less meat. That's something I'm trying to do; I'm not a, know, I, there's a lot more I can do in that area. But it's getting increasingly difficult for me just to justify eating very much meat if I think about how important it is to protect the Amazon forests and other forests of the earth. Another thing we can do is waste less food. We should do that anyways. But yeah, do you want to protect the Amazon forest? Waste less food, eat less meat.

Max Holmes is the Acting Director and Executive Director of the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Falmouth, Massachusetts. (Photo: Chris Linder)

CURWOOD: Max, before you go, what gives you hope, in terms of addressing the climate emergency?

HOLMES: What gives me hope is that we know what needs to be done. What gives me pause is because we've known for a while and we haven't done it. So we have to figure out how to motivate the action to do what needs to be done to get this thing under control. The other thing that gives me hope is I have kids, and I think about what their future holds. And that's kind of what keeps me coming to work every day and doing everything I can to try to change the direction that we're headed.

CURWOOD: Max Holmes is the Acting President and Executive Director of the Woodwell Climate Research Center. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today, Max.

HOLMES: Thanks, Steve, I enjoyed it.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth