November 12, 2021

Air Date: November 12, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Cashing Out Coal

View the page for this story

At the COP26 climate talks, the US and European nations agreed to provide $8.5 billion in financing to help South Africa phase out its use of coal power. South Africa, which is experiencing yet another wave of power outages, gets most of its electricity from burning coal and is the largest carbon emitter in Africa. Jesse Burton, a senior associate with the think tank E3G, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss what international aid means for South Africa's energy transition. (10:56)

Tropical Forest Riches

View the page for this story

Tropical forests are a treasure trove of biodiversity and contain vast stores of carbon that threaten the stability of Earth’s climate system if released through deforestation. Max Holmes, acting President and Executive Director of the Woodwell Climate Research Center, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the threats to tropical forests and explain the importance of protecting them from further degradation. (12:00)

Saving the Tropical Forest Carbon Bank

View the page for this story

At the COP26 climate talks in Glasgow more than 130 countries representing 90 percent of the world’s forest cover pledged to end net forest loss by 2030. Rhett Butler, editor in chief of the environmental news agency Mongabay, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to provide some perspective on the declaration. (07:36)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Host Bobby Bascomb and Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra discuss a genetic diversity crisis in orca whales, and why non-native water buffalo pose an emerging threat to the Amazon rainforest. In the history calendar they look back to perhaps the first and only trash pickup in space. (05:04)

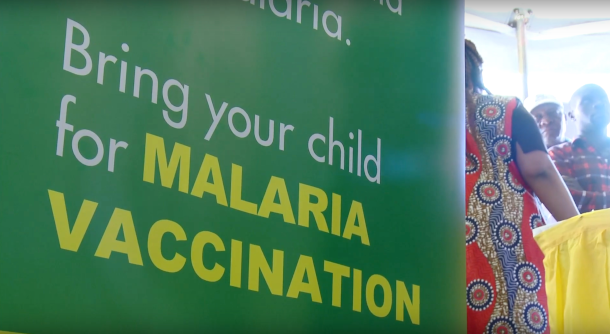

Malaria Vaccine Gets Green Light

View the page for this story

Malaria is responsible for almost a half-million deaths every year, many of them among children. Researchers have been working on developing a malaria vaccine for nearly a half century, and at last the World Health Organization has given its first-ever stamp of approval to a malaria vaccine. Immunologist Dyann Wirth of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health joins Living on Earth's Aynsley O'Neill for more. (11:04)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

211112 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jesse Burton, Rhett Butler, Max Holmes, Dyann Wirth

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

COP26 emphasized tropical forests are crucial for the climate.

HOLMES: Forests with this vast amount of carbon that they contain, it takes them a long time to build it up. It’s not a year, it’s not 10 years, it’s in many cases it’s not even a hundred years. It’s longer than that to build up all that carbon. You chop those trees down, you burn them, all that carbon goes back to the atmosphere right away.

CURWOOD: Most countries, including Brazil, agree to halt deforestation by 2030.

BUTLER: So, it's a big deal that Brazil signed it. There are some caveats though, so there's been an emphasis on net zero deforestation, which means that clearance of national forest can still happen, but it could be quote-unquote offset by plantations. So that's a significant loophole.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Cashing Out Coal

The Majuba coal power station powered by Eskom is located between Volksrust and Amersfoort in Mpumalanga, South Africa. (Photo: James Oatway for CER)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. As we prepared this broadcast delegates at the COP26 UN Climate Summit in Glasgow were still negotiating, so we’ll have the final results in next week’s show. The questions remaining include how global warming gases might be taxed or traded in markets and what more will be done to help less developed countries deal with loss and damage from climate disasters. Any agreements will be enforced on the honor system, as COP 26 did not try to create a binding treaty that would require formal ratification by nations, as was done for the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 at COP 3. So, it’s on the basis of handshakes that many, but not all, of the nearly 200 nations in Glasgow agreed to reduce methane emissions, move away from gasoline and diesel-powered cars, and protect the world’s forests. We’ll have more on forests commitments later in this broadcast. A big handshake came between the US and China who put aside their geopolitical tensions and issued a joint communique reestablishing an Obama era working group that facilitated contact between US and Chinese local governments, academics, and others. Yet to be agreed upon, as we bring you this show, is draft language that calls for the phase-out of fossil fuel subsidies and the use of coal. And even if those provisions don’t survive the final rounds of negotiations the US and several European nations agreed to provide $8.5 billion dollars to help South Africa phase out its use of coal. Despite plenty of sunlight more than 80% of South Africa’s electricity comes from coal, making it the largest carbon emitter in Africa. Eskom is the state utility company that provides more than 90 percent of the electricity used in South Africa and it’s currently drowning in more than 27 billion dollars in debt and as a result can’t keep the lights on all the time. Joining us now is Jesse Burton, a senior associate with the think tank E3G who provides analysis and advice for socially just coal transitions in South Africa and globally. Welcome to Living on Earth Jesse!

BURTON: Thanks for having me.

Delegates at the Opening Ceremony of COP26 in Glasgow, where the US and several European nations agreed to provide $8.5 billion in financing to help South Africa phase out its use of coal. (Photo: Karwai Tang / UK Government, COP26, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, tell me how does the national grid work in South Africa, especially when it comes to coal?

BURTON: Well, actually at the moment, it's not working. We're facing something called loadshedding, which is a word which is very familiar to South Africans which really just means Eskom is not meeting demand. And kind of what's happened is South Africa is incredibly coal dependent, so we get about 87% of our electricity from.. from coal fired power plants, a little bit about 5% from wind and solar and a small contribution from nuclear and hydro and some imports. What's happened is that that Eskom has been building some new coal fired power plants, Majipa and Kasile, and they're not working very well. And at the same time, the rest of the fleet is very old, kind of similar to the US in many ways. A lot of the plants were built in the 60s and 70s, and 80s. And they haven't been maintained very well. And they're kind of they're falling over like an old car that you haven't maintained. And so, Eskom's big challenge at the moment is how does it get those coal plants that are still under construction to work? Can it maintain some of the old ones in the short term? And how to think about phasing out the coal in the medium and longer term as it transitions away?

Emissions from coal include sulfur dioxide (S02), nitrogen oxides (NOx) and particulates all of which contribute to respiratory illnesses and lung disease. (Photo: James Oatway for CER)

CURWOOD: What are the health costs of the coal industry in South Africa? The people in the mines and the people who are running them are now people of color. It's not the same thing as under apartheid. But coal, well puts out a lot of particulates.

BURTON: Yeah, it's an interesting question. I mean, paradoxically, coal has in some ways been the backbone of development in South Africa. It's been this cheap input for cheap electricity which brought a whole lot of development, created the basis for all the industry in the country. At the same time, it's been accompanied by this deep environmental injustice. Most of the coal mines and the coal plants are in sort of 100-kilometer radius in this province called Mpumalanga. And so, you have air pollution problems, you've got water pollution problems, the most polluted river catchment in the country that Olifants catchment runs through the mining areas. From an air pollution perspective you know, you've got extraordinarily high levels of particulates, but also SOx and NOx. To the point where the.. the government's own health study, which was recently leaked, it wasn't even released, it was discovered through some litigation that civil society is undertaking to try and force the government to implement its own air pollution laws. But in that process, they discovered that the government's modeling sees that air pollution in Mpumalanga leads to the premature death of about 5,000 people per year, has twice as much asthma in the region as there is anywhere else. So, it just comes with these enormous costs. On top of that, you know, you've got a lot of abandoned mines. You know, the mines now are better, they're doing rehab as they go and that sort of thing but historically, there were a lot of mines that were just let go that were abandoned that companies went under, you know. So, there's also issues around degraded land, and this really starts to impact people's health. We hear from activists on the ground that people who've grown up in the region who want to work in mining, because this is the only sector that has any growth in the area, in part because other sectors are put at risk by these kinds of impacts, you know, and health and water and air.

If you've grown up in the area, people are often too sick to pass the health tests that you need to pass to get into mining.

CURWOOD: Really?

"SA’s coal industry, the world’s fifth-largest, employs 90 000 miners, generates 80% of the country’s electricity, and supplies the feedstock for about a quarter of the country’s liquid fuel, all at a time of soaring unemployment and frequent blackouts."https://t.co/xuFmQ3RkZ0 pic.twitter.com/yMiBLwiVHi

— Centre for Environmental Rights (@CentreEnvRights) November 9, 2021

BURTON: Yeah.

CURWOOD: You're saying that if you live near the mines, where the jobs might be in your neighborhood, if you grew up there, your health has been so compromised, that you won't qualify to go and work at the mine

BURTON: Often, yeah.

CURWOOD: Whether in the office or down in the pit?

BURTON: Exactly and it's very hard. I mean, South Africa as a whole has incredibly high levels of unemployment. They've always been very bad, but post-COVID it's even worse, you know, 45% unemployment in the country and slightly higher in Mpumalanga province itself. And that's even worse for youth unemployment. If you're a young black woman, unemployment levels are almost 70%. So, it's incredibly difficult.

CURWOOD: So, during the Conference of the Parties in Glasgow, the US and a number of European nations pledged to put together eight and a half billion dollars for South Africa's transition away from coal. How precedented is this? And how important is it for South Africa?

Aerial view of the Majuba coal fire plant. A study conducted by the state-owned Council for Scientific and Industrial Research conducted research that found that more than 5,000 South Africans die annually in the nation's coal belt because of lack of air quality enforcement. (Photo: James Oatway for CER)

BURTON: I think it's hugely important. I mean, this is the first time a country led donor supported process like this is going to unfold in this way. You know, the donor countries came together, and then they've pledged this 8.5 billion and the South African government came together, and they put together their asks around where they needed support and they've signed this political declaration at COP, and it's huge. I think this is a test case for seeing how coal intensive developing countries, and there are a lot of them, can be supported in this way. You know, it's fascinating to see because now we’re getting down to talking, you know, what is it going to take to decarbonize the power sector or to get to that low NDC range of kind of enroute to decarbonization. Well, it requires a huge build out of transmission infrastructure. You know, we've got to build 40 gigawatts of wind and solar over the next decade, at the moment we've only got six gigawatts installed, so it's a huge scale up. And this just energy transition partnership is a way for developed countries to kind of step up and deliver on the finance that they've been promising for many years and the support they've been promising to developing countries to do this.

CURWOOD: So, what about interest rates? Because in the United States, the government borrows for around, say. 1% and in South Africa, what's that, at five or six and even more in the private sector. To what extent is the international community committing to having the loans be at the same rate that people going green in the Global North can borrow the money?

BURTON: Well, this is what I would expect to see. I think it's a really good question. This, I think, is precisely the kinds of negotiation that will need to happen in the next six months. I would expect to see the developed countries say yes, we're borrowing at 1% or less, and we offer to transfer some of that value to you. Because it's very important for South Africa, we can't really afford to indebt ourselves further. If the terms of those concessional loans are not good enough. We can't grow faster; we can't afford to. The people in Mpumalanga who don't have work can't afford to. So, this is really that context. What made me very optimistic about it is that the political declaration very much centers just transition. So, it acknowledges all of these constraints. It acknowledges that South Africa has an employment crisis, that looking after fossil fuel workers is important that you have to look at the mining value chain and the communities in Mpumalanga. But exactly how all of those pieces fit together is not fully known yet.

Jesse Burton is a Senior Associate of E3G providing analysis and policy advice on coal transitions in South Africa and globally. She is based in Cape Town, South Africa where she also works as a researcher at the University of Cape Town. (Photo: Courtesy of Jesse Burton)

CURWOOD: How hopeful are you, Jesse, that this will all come to pass that the money will be there that there'll be this conversion going forward? In South Africa with a utility, which has been frankly, troubled for decades.

BURTON: I'm feeling remarkably hopeful. I mean, there's always the risk. There's the risk the money doesn't come, there's a risk that the money comes on the wrong terms. You know that it's too expensive to actually do a just transition, there's a risk that it goes only into renewable energy, and not so much into the aspects of the core value chain where I see a lot of future risk for people, you know, especially looking after miners looking after communities. But I'm very optimistic, I think it's the first time that in South Africa, we're talking a lot about what is really going to be needed to make sure that the transition happens in a way that is fair, not just a transition happens, that it is actually a just transition, and that is finance to support that. And it is a long-term process, where finance can keep coming in to support that. And it also demands of the South African government that they think a lot now about their plan on going into the future. You know, what do they actually want? How do they see this unfolding? What are the needs for retraining or relocation or new skills development or SMMEs, small, small, medium businesses in that core region. There are more than enough jobs in renewable energy to offset the job losses in the coal mining and the coal power plant chain but of course, they're not always in the same place as the existing coal jobs. So, there's a lot of work to be done to say, how do we put some of these renewables in the coal region? How do we make sure that workers in renewable energy plants are unionized? You know, because it's very dispersed. How do we make sure that the wages are similar or better? So that all of those kind of things line up? I feel quite inspired, actually. I hope it happens and this of course, you know, we wanted to be ambitious, we want it to be transformational and we have to work to make that happen. It won't just happen automatically. But I think the runway is there to have a just transition in South Africa and that makes me really excited.

CURWOOD: Jesse Burton is a senior associate at E3G, speaking to us from South Africa. Thanks so much Jesse for taking the time with us today.

BURTON: Thank you so much for having me.

Related links:

- Learn more about Jesse Burton

- E3G | “No New Coal By 2021”

- BBC News | “COP26: South Africa Hails Deal To End Reliance On Coal”

- Watch this documentary produced by KCET that looks into coal mining in South Africa

- NPR | “Draft Agreement At The COP26 Climate Summit Looks To Rapidly Speed Up Emissions Cuts”

- Human Rights Watch | “South Africa’s 'Deadly Air' Case Highlights Health Risks from Coal”

- The Japan Times | “The Cost Of Coal In South Africa: Dirty Skies And Sick Kids”

[MUSIC: Vusi Mahlasela, “Natate Mahlasela” on The Voice, by Vusi Mahlasela, ATO Records/BMG]

BASCOMB: Coming up – To protect the climate, protect tropical forests. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

ANNOUNCER: Support also comes from friends of Smeagull the Seagull, and Smeagull’s guide to wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you. That’s Smeagull, S M E A G U L L, smeagullguide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Pacific Express, Tony Cedras, Jonathan Butler “7th Avenue” on Cape Jazz, Templit Ltd for Mountain Records]

Tropical Forest Riches

A tropical rainforest in the Danum Valley Conservation Area, Malaysia on the island of Borneo. (Photo: Jeremy Bezanger on Unsplash)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

One of the biggest promises made at COP26 alongside the main negotiations were pledges from more than 130 countries to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by the year 2030. More on that later in the show, but first let’s talk about why tropical forests are such an important part of flattening the carbon emissions curve. With me now is Max Holmes, he’s acting President and Executive Director of the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Falmouth, Massachusetts. Welcome to Living on Earth, Max!

HOLMES: Thanks, Steve. It's great to be here.

CURWOOD: It's our pleasure. So, tell me, why are tropical forests in particular so important to the carbon cycle?

HOLMES: In short, because tropical forests hold a vast amount of carbon in them. And the concern is that if the trees are cut down, if they burn, if human activities otherwise get rid of those, those trees, that carbon that's been locked up in the trees for decades and centuries, in many cases, goes to the atmosphere and leads to more warming. A few numbers that help put this in context: first, I'll just start with the amount of carbon that's in the atmosphere right now -- carbon is carbon dioxide. So, this is about 850 billion tons of carbon in the atmosphere, currently. All the forests on Earth contain about 500 billion tons of carbon, that's carbon in the vegetation, so in the trees, the stuff that you see above ground, as well as the roots below ground, so around 500 billion tons in trees. Tropical forests have about 300 billion tons, so something like 60% of the global forest carbon is in tropical forests, so a really big number. And so, you can see how losing carbon from tropical forests can have a big impact on how much carbon is in the atmosphere, and thus how much the earth warms.

CURWOOD: And by the way, how much do humans put into the atmosphere every year at this point?

Deforestation from July 4, 2000 - July 16, 2019 around BR-163, a highway in the northern Brazilian state of Pará that links soy-growing areas with an ocean-going port on the Amazon River. (Photo: Lauren Dauphin, NASA Earth Observatory, public domain)

HOLMES: Human activities right now are putting something around eleven, eleven and a half billion tons per year into the atmosphere -- around ten billion tons from fossil fuel combustion, so that's oil, gas and coal that we're using, and around a billion or a billion and a half tons from land use change from, from deforestation.

CURWOOD: So crude mathematics would say if you do that for the last 30 years, since we've been talking about the climate agreement, we're getting up there at least a couple of hundred, maybe even 300 billion tons of carbon we've put into the atmosphere just since we started talking at the UN.

HOLMES: Yeah, that's right, we have put a lot of carbon into the atmosphere since we started talking about this problem, recognizing the problem. And that just means that we have to work a lot harder now. It's getting a lot more difficult and a lot more expensive to reverse course now. But that also just makes it a lot more urgent that we get to work on this right away. Of the carbon that we do put into the atmosphere, only about half of it stays there. The other half gets split between the ocean and land. So, the land is sucking carbon out of the atmosphere and the ocean is also absorbing carbon. So, they're both doing us a big favor, helping to pull some of that carbon that we put into the atmosphere back out.

CURWOOD: Max, by the way, where are the main tropical forests in the world? There's the Amazon, of course, but talk to me about the group of them.

HOLMES: Yeah, the largest is the Amazon, the one that we all think about and hear about a lot. The second largest is in the Congo, also just a vast tropical forest. And then the forests of Indonesia are also super important -- not as large, but they're very carbon rich. And they're all under threat. So, there's been some pretty rapid change underway in the Amazon right now, that, that needs to reverse. The Congo, ironically, it is more pristine, it has had less direct human intervention. It doesn't mean that there hasn't been any, but there hasn't been widespread clearing in the Congo for the most part. It's not necessarily that there's been particularly enlightened environmental policy. It's been an unstable region, and because of that, you know, big multinational corporations haven't come in there. It hasn't really been safe for lots of the activities that have led to deforestation in the Amazon, for example. So, it's this situation where, as peace and stability increase, we hope, we certainly hope those things increase in the Congo, that could lead to additional threats to the forests.

CURWOOD: And Indonesia?

HOLMES: Yeah, so some of the big activities happening there that lead to deforestation, so palm oil plantations are a big driver of that; forests are cleared to plant palm trees to create palm oil. A lot of those forests in Indonesia, they're, they're on peatlands, which are very carbon rich areas. So, you get the, let's say, a double whammy when you clear those forests. Not only are you losing the carbon that's in the trees, but there's a lot of carbon locked up in those peatlands soils in some of those areas that you're also -- once they dry out, associated with the clearing of the land, the soils dry out, and that carbon that's been locked up in the peat for a long time can also be released to the atmosphere. So that's contributing a lot of carbon to the atmosphere.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about how the storage of carbon in old growth tropical forests compares to young, regrowing or planted forests there and elsewhere in the world.

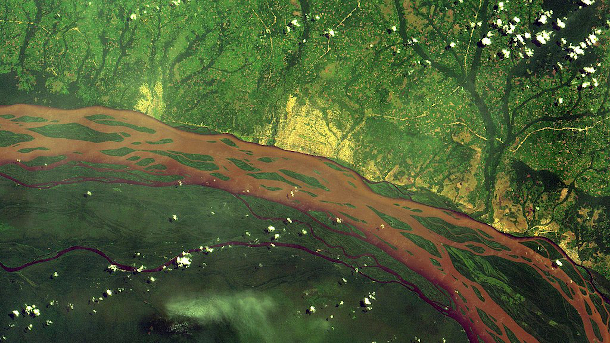

A satellite image of the Congo River running through the rainforest in the Democratic Republic of Congo. (Photo: Coordenação-Geral de Observação da Terra/INPE, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

HOLMES: Yeah, so that's an interesting question. And I'm looking out my window right here in Woods Hole, in Falmouth, on Cape Cod, and there are beautiful trees out the window. And, you know, all of those trees started with a little seed, a tiny little seed. And now they're these massive, you know, 100 feet tall, 100 and some feet tall, with loads of carbon in their bodies. And you think about, okay, where did this carbon come from? The carbon in those trees -- and it's mainly carbon, that's, that we're looking at when you're looking at a tree -- that all came out of the atmosphere, the trees pull that carbon out of the atmosphere, that carbon dioxide, and they use that to build themselves, to build the tree. So, you know, sometimes it's argued that, yeah, you can, you know, cut down trees and the forests are going to regrow. This is a renewable resource. On the one hand, that's certainly true. The issue is the timeframe. I like the analogy of a bank account. You can think of a savings account that maybe you started as a kid, and you're, you know, every year or every month, you're putting your allowance into that, and you're putting some money into it, year after year, and over time, you build up some, some amount of money. And it took a long time, a lot of work to build up that bank account, that savings account balance, but you can blow it in a hurry if you go out and buy that thing that you've, you know, that new car or whatever it might be that you're interested in, and you go down to zero. Can you renew that, that amount of money that's in that savings account? Of course, you can, but it's going to, again, take a lot of time to do it. And it's a similar thing with forests. Forests with this vast amount of carbon that they contain, it takes them a long time to build it up. It's not a year, it's not ten years, it's in many cases, not even a hundred years. It's longer than that to build up all that carbon. Just like you can empty out your bank account in a hurry, you can empty the carbon out of a forest in a hurry. You chop those trees down, you burn them, all that carbon goes back to the atmosphere right away. Yeah, you can build it back. But it takes a lot of time. With climate change right now, we don't have that time. We've got to keep the carbon in the forests that are standing; where we can restore forests, we need to start doing it, it will pull carbon out of the atmosphere, but it's gonna, it will take them a long time to restock that balance they'd started with before we deforested.

CURWOOD: Max there's some research that we reported on earlier this year that suggests that parts of the Amazon are so degraded that they're becoming sources of carbon, rather than serving as carbon sinks, that is absorbing it. And then there are even other compounds coming out of the Amazon, such as methane, and nitrogen compounds, that also can, can warm the atmosphere. How close do you think we're at a tipping point where the tropical forests, and the Amazon in particular, is no longer able to function as the lungs of the planet?

Rainforest in Kinabalu Park, Malaysian Borneo (Photo: Dukeabruzzi, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

HOLMES: Yeah, so it's kind of scary news, some of this latest research, and it does seem to show that the Amazon is getting really close to that point where instead of pulling carbon out of the atmosphere on net, it's turning into a source of carbon to the atmosphere. I think some of the latest studies I've seen have suggested that the Brazilian part of the Amazon, which is the biggest chunk of the Amazon, it may already be a small carbon source to the atmosphere. The Amazon, overall, still seems to be a small carbon sink, but we're getting close to that point where it's going to be a net carbon source overall. Now, with respect to, are we going to hit some tipping point, that's certainly a concern. One of the things that, that maintains the forests of the Amazon is precipitation that's generated by the forest. So, trees need a lot of water to survive, they also lose a lot of water through their leaves to the atmosphere. That water that's lost, that water vapor that's lost, can lead to more precipitation. So, water loss from one tree may lead to precipitation that sustains another tree in the Amazon farther downwind. If you lose enough trees, if you do enough deforestation that can impact the amount of rain that falls in the Amazon, it can lessen the amount of rain that falls in the Amazon. And that can cause the forest to die. So, there's concern that, you know, there have been estimates that if you deforest 40% of the Amazon, that might be enough to hit that tipping point where the whole thing just collapses. There are some other studies that suggest it might be 20% -- if you deforest 20%, it might put you over the edge where the forest can't maintain itself. That's within range, so that just means that, given we don't know exactly where that tipping point or threshold is, all the more incentive to slam on the brakes right now, while we can.

CURWOOD: The countries who have pledged to stop deforestation in less than 10 years feel like they're taking pretty good action. But we know what actually happens isn't just up to what the leaders decide or pledge at a conference in Glasgow. What else would you recommend to people listening to this doing? What can people do to help in the situation of the threats to our forests?

HOLMES: Yeah, I mean, it gets back to thinking about the drivers of forest loss, globally and in the tropics. One of the big drivers is just climate change overall. The Earth's climate is changing, it's human activities that are driving those changes, that's leading to forest loss, forest dieback, fires, insect outbreaks, all those things. So, you know, there's the list of individual activities, community activities, family activities, business activities we can all do to help put the brakes on climate change. Another of the big drivers of deforestation in the tropics, in the Amazon, is agriculture, right? So, they're clearing forests to grow soy. Why are they growing soy? The soy is not to feed us. There's, yeah, okay, we eat some soy. But it's not primarily to make tofu or something like that that we're eating, it's to feed animals that we're eating. And that is a very big driver of deforestation in the Amazon. So, what can we do as individuals? We can think about what we're eating, we can eat less meat. That's something I'm trying to do; I'm not a, know, I, there's a lot more I can do in that area. But it's getting increasingly difficult for me just to justify eating very much meat if I think about how important it is to protect the Amazon forests and other forests of the earth. Another thing we can do is waste less food. We should do that anyways. But yeah, do you want to protect the Amazon forest? Waste less food, eat less meat.

Max Holmes is the Acting Director and Executive Director of the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Falmouth, Massachusetts. (Photo: Chris Linder)

CURWOOD: Max, before you go, what gives you hope, in terms of addressing the climate emergency?

HOLMES: What gives me hope is that we know what needs to be done. What gives me pause is because we've known for a while and we haven't done it. So we have to figure out how to motivate the action to do what needs to be done to get this thing under control. The other thing that gives me hope is I have kids, and I think about what their future holds. And that's kind of what keeps me coming to work every day and doing everything I can to try to change the direction that we're headed.

CURWOOD: Max Holmes is the Acting President and Executive Director of the Woodwell Climate Research Center. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today, Max.

HOLMES: Thanks, Steve, I enjoyed it.

Related links:

- Learn more about the importance of the tropics

- About Max Holmes

[MUSIC: Bill O’Connell, The Latin Jazz All-Stars, “Tabasco” on Heart Beat, Savant Records]

Saving the Tropical Forest Carbon Bank

Forest family photo of World Leaders at COP26 in Glasgow (Photo: Karwai Tang / UK Government, COP26, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, tropical forests are critical to the world’s carbon budget and ensuring a livable climate. And at the recent COP26 in Glasgow more than 130 countries pledged to end net forest loss by 2030. The countries that signed on represent roughly 90 percent of the world’s forest cover and 85 percent of tropical forests. The Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use, as it’s known, includes roughly 19 billion dollars in related funding commitments. Rhett Butler is editor in chief of the environmental news agency Mongabay, which focuses on tropical forests, and he joins us now to give us some perspective on the declaration. Rhett, welcome back to Living on Earth!

BUTLER: Thank you. It's a pleasure to be here.

BASCOMB: Well, halting deforestation in that much of the world's tropical forests. I mean, it's a wonderful goal. But, practically speaking, how could they go about that?

BUTLER: One of the ways that a lot of conservation groups are recognizing is critical for reducing deforestation is recognizing local land tenureship. So, helping indigenous local communities secure land rights because there's plenty of research to show that these communities have the lowest deforestation rates in their traditionally managed forests. And so, if we look at like where forests exist today, a large share of those forests are in territories that are stewarded by indigenous local communities. So, a lot of groups are now rallying around the idea that helping strengthen land rights is a key mechanism for reducing deforestation. Beyond that, forest monitoring, it's got a lot better. So, we're able to see where deforestation and forest degradation is occurring now. So, we no longer have ignorance as an excuse for not taking action. And then there's some groups that have been pushing more for payments for ecosystem services. So, the idea of looking at the carbon value of those forests and then paying countries to, to preserve them.

The Amazon Rainforest, an important carbon sink at risk of deforestation. (Photo: Diego Perez, USDA Forest Service, NASA, public domain)

BASCOMB: Well, as we said, roughly 130 countries have signed on to this declaration, including Brazil, which is home, of course, to the majority of the world's largest tropical rainforest, the Amazon. But deforestation rates in Brazil have been marching steadily upwards for the last decade or so. And even more so since Jair Bolsonaro became president almost three years ago. So, what do you make of Brazil signing on to this pledge to halt deforestation?

BUTLER: So, it's a big deal that Brazil signed it, there are some caveats, though. So, there's been an emphasis on net zero deforestation, which means that clearance of national forests could still happen, but it could be quote-unquote, offset by plantations. So that's a significant loophole. And then Brazil's leadership has been focusing on illegal deforestation. So illegal deforestation is, you know, a subset of overall deforestation. But what's been happening in Brazil under the Bolsonaro administration, is that deforestation that was, you know, once illegal is now being legalized. So essentially, environmental laws are being relaxed. So, it's kind of like a shifting baseline.

The devastating results of deforestation. (Photo: Dikshajhingan, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BASCOMB: So, focusing on illegal deforestation doesn't do you much good when you keep changing the laws to make deforestation legal.

BUTLER: Yeah, exactly. And then also when you're not enforcing the law.

BASCOMB: Well, at the other end of the spectrum is Indonesia, which is also signed on to this declaration. And as I understand it, Indonesia has been really effective at reducing deforestation rates. Can you tell us about that? And what are they doing right there?

BUTLER: Well, so yeah, Indonesia seen a big drop in deforestation over the past five years from a pretty high baseline. So, if we compare the first half of the decade to the second half of the decade, deforestation fell by about a million hectares, we're talking primary forests, which is a lot. So why is it happening? So, there are a few things. So, there's both factors that are, that are within Indonesia's control, and there are macro economic factors that are sort of outside of Indonesia's control. So, within the things that Indonesia could control, in the early 2010s, they established a moratorium on converting certain types of forests for plantations. So, the oil pump plantations and wood pulp plantations. And so that moratorium has been renewed every, every few years, and remains in place. And so that is probably a factor in the reduction, deforestation. Sort of factors outside of Indonesia's control have been the price of palm oil. So, until about the past year, palm oil prices have been sort of declining, relative to the, the historical highs where they've been, you know, in the first part of the decade. And so, since palm oil is the most profitable form of land use in a lot of these tropical forests in Indonesia, if the price is falling, then there's less incentive to actually clear forest. And so that's, that's also a factor.

Palm oil plantations are common in Indonesia and a major cause of deforestation of tropical forests. (Photo by CEphoto, Uwe Aranas, Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: Well, this new declaration is accompanied by about $19 billion in funding commitments. How might that be spent in an effective way, do you think?

BUTLER: I think a lot of that money is probably gonna go towards mechanisms that were previously applied, which hasn't really worked that well so far. But the fact that it is a significant amount of money is, you know, is important. So given this large push around securing land rights and recognizing land rights of indigenous peoples, I would expect to see some of that money going to funds that would then be reallocated towards those efforts, especially in geographies where there are large tracts of forests that are stewarded by indigenous people. So especially like in the Amazon and Congo basin, and even parts of Indonesia. So that money will go into technological systems. So, we have decent monitoring now, but the carbon accounting around land use emissions is still pretty poor, there are a lot of gaps, and some countries aren't exactly being transparent in terms of what they report to the UN versus what's actually happening. So, I'd expect to see some of that money allocated towards kind of the accounting and monitoring. And then I think a lot of the money is just going to go towards, you know, conventional conservation initiatives. So, you know, these are typically initiatives that are implemented by either governments or NGOs, which include both protected areas, but then also conservation measures that are outside protected areas. So, working towards more sustainable landscapes, restoration projects, so that would be both allowing degraded areas to recover naturally, but then also doing tree planting and afforestation. So, I think those are all where this money will probably be applied.

BASCOMB: Now, you mentioned earlier the New York Declaration on Forests, which was endorsed at a UN Climate Summit in 2014. Can you compare that for us to this more recent pledge in Glasgow?

The Amazon Rainforest is densely covered and collects an immense amount of carbon from the atmosphere. (Photo: Phil P Harris, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.5)

BUTLER: Yeah, I mean, so the New York Declaration on Forests was both more limited and more expansive in scope. And so, I'll clarify what that means. So, there was a smaller number of national governments that signed the agreement. So, it was 39, endorsed the declaration, but then there were sub-national entities about 20. So sub-national entity would be like a state or province that signs the declaration, whereas the national government does not. And then there were also companies, NGOs, and indigenous communities that signed it as well. It was a smaller group of national governments that signed it, but it was a broader array of society and groups, institutions that signed the agreement. That said the, the amount of land that was covered by that declaration was much smaller. So, the New York signatories, it was about 1.5 billion hectares of tree cover, whereas the Glasgow signatories represent about 3.5 billion hectares. So, it's more than twice. The New York Declaration aimed to halve deforestation by 2020 and end it by 2030. The Glasgow declaration aims to quote-unquote, halt forest loss by 2030. So those targets are aligned.

BASCOMB: Rhett Butler is founder and CEO of the environmental news agency Mongabay. Rhett, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

BUTLER: Thank you so much for having me.

Related links:

- Mongabay | “Do Forest Declarations Work? How Do the Glasgow and New York Declarations Compare?”

- Mongabay | “What Countries Are Leaders in Reducing Deforestation? Which Are Not?”

[MUSIC: The David Wax Museum, “The Persimmon Tree” on Carpenter Bird, based on traditionalson jarocho songs/arr.David Wax, self-published]

BASCOMB: The next meeting of the Living on Earth book club is coming up on November 18th at 6:30 pm eastern. We’ll be talking with Devi Lockwood about her book 1,001 Voices on Climate Change. She sets out to bike around the world collecting real, personal stories about how flood, fire, drought, and rising seas are changing communities. From Sweden to China, and the Canadian Arctic to the Peruvian Amazon, she covered every continent except Antarctica. You can register for this free event at loe.org/events. That’s loe.org/events. And if you like, email a question in advance for Devi Lockwood to loebookclub@loe.org. That’s loebookclub@loe.org. See you there!

[MUSIC: The David Wax Museum, “The Persimmon Tree” on Carpenter Bird, based on traditionalson jarocho songs/arr.David Wax, self-published]

CURWOOD: Coming up—The good news for people in the tropics, there’s now an approved malaria vaccine. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Antonia Carlos Jobim, “The Red House” on Wave, UMG Recordings]

Beyond the Headlines

Killer whales hunt a seal in Monterey Bay, California. (Photo: Robin Agarwal, Flickr, CC By NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

BASCOMB: Well, it's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Bobby, I've got something that probably not too many folks know, unless they like to read studies from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology on orca whales. Orca pods are very distinct throughout the world, and that according to this research, led by Andrew Foote, orcas may be heading toward a really serious genetic diversity problem which of course can lead to inbreeding and a whole lot of ills.

BASCOMB: Why is there a problem with their genetic diversity?

DYKSTRA: Well, historically, orcas started out in warmer water and 1000s of years ago, the only warm water was near the equator. As the Ice Age ended, orcas spread out to north and south. And now they occupy a lot of very distinct areas, like the Orca pod in Puget Sound. Certainly, the most famous one in US waters. Those orcas never intermingle with other orca populations. And for most of these 1000s of years, they've been breeding unto themselves, that can only lead to bad things.

BASCOMB: Right. Too much inbreeding would cause some, you know, health problems and any disease that they're all susceptible to could wipe out a whole pod, I should think.

DYKSTRA: That's one of the biggest concerns. However, they're also looking at another concern. And that's that the warming of the oceans through climate change, may push orcas even farther away from the equator and to the poles. That could create hardship for orca pods. It also, possibly, theoretically, could drive orca pods together, sharing the same waters and possibly mingling with each other and reducing diversity problem.

BASCOMB: Hmm, yeah, could go either way. Something to keep our eye on anyway. What else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, there's something called buffalo frenzy going in the Amazon rainforest. No, it has nothing to do with buffalo chicken wings, it has nothing to do with the city of Buffalo. It has to do with the water buffalos, and they're increasingly prized by farmers and ranchers that are clearing the Amazon. Water buffalo can provide the same products, meat and dairy, that cows provide but water buffalo are a lot bigger and can provide more of those products, they could do so at even greater harm to the fragile Amazon ecosystem.

BASCOMB: Hmm, well, cows are plenty harmful. I mean, you have to completely cut down the forest to be able to grow them and they can only graze there for so long before you have to cut down new pasture for them, but buffalo are even worse, you say.

The clearing of the Amazon rainforest for grazing domestic water buffalo has encroached on 18 indigenous reserves in the Autazes municipality. (Photo: Kate Evans, CIFOR, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: The water buffalo can occupy larger areas, which is a problem. They can do more damage to those areas, which is a problem. They can out graze the areas that are cleared, which is still another problem. It all adds up to multiplying an already potentially lethal threat to the world's most important rainforest.

BASCOMB: And of course, both Buffalo and cattle are not native to the Amazon. So, you know, generally, when you introduce a lot of non-native species, it's a recipe for disaster for the ecosystem.

DYKSTRA: A water buffalo sized non-native species especially.

BASCOMB: Yeah, for sure. All right, well, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

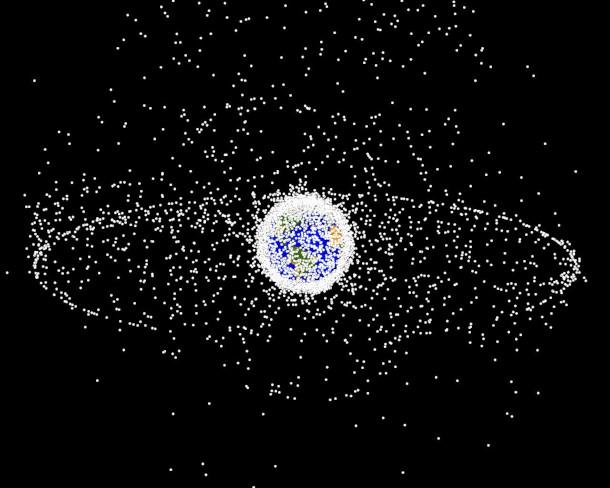

DYKSTRA: November 12, 1984. The first and, as far as we know, the only trash pickup in space. Two astronauts from the Space Shuttle Discovery, Joseph Allen and Dale Gardner did a spacewalk. They managed to wrangle a disabled satellite, put it in the space shuttles cargo hold and bring it back to Earth. That's one down and about a half a million pieces of space junk to go. Space junk can be as tiny as a bolt, it can be as big, apparently, is a satellite.

BASCOMB: Hmm, yeah. Well, you can certainly see how that could be a huge hazard for space travel. You know, it's just shocking too though. I mean, we've polluted our own planet, and we've even polluted this space around our planet. There's no end to the garbage that we produce, I suppose.

A computer-generated representation of objects in Earth orbit currently being tracked. (Photo: NASA image, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

DYKSTRA: Right. And picking up that one satellite in 1984 was a bit of a demonstration. In no way should we think that picking up space trash, especially a half a million bits of it is ever going to be easy, because as we all know, in space, you cannot call a tow truck.

BASCOMB: No, certainly not. All right. Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with environmental health news. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Bobby, thanks a lot. I'll talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: And there’s more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That’s loe.org.

Related links:

- Hakai Magazine | “Killer Whales’ Low Genetic Diversity Offers a Warning for the Future”

- Mongabay | “Indigenous Lands Under Siege as Buffalo Frenzy Grips the Amazon”

- The New York Times Archive “Astronauts Snare Errant Satellite for the First Time”

[MUSIC: Nashville Mandolin Ensemble, “Where No Mandolin Has Gone Before – a/k/a Star Trek” on Plectrasonics, by Alexander Courage, CMH Records]

Malaria Vaccine Gets Green Light

The World Health Organization has announced their recommendation of the RTS,S malaria vaccine. (Photo: UNICEF Ethiopia, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: A big risk for people living in or even visiting in the tropics is malaria. Fever, shaking, chills and excruciating pain are hallmarks of this tropical disease that is also found in some primates and transmitted to humans by mosquitoes. Malaria infects more than 200 million people every year around the world, kills about 400,000, and half of these victims are children in Africa. After nearly fifty years of research scientists have finally developed a vaccine for malaria that has won the first-ever approval by the World Health Organization. This first vaccine is considered to be about 40 percent effective, and while it is less than perfect and requires boosters, it is being heralded and deployed, as it is better than nothing to help human immune systems ward off malaria, even as efforts continue to develop even more effective vaccines. Dyann Wirth is an immunologist and Professor of Infectious Disease at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She spoke with Living on Earth's Aynsley O'Neill.

O'NEILL: Please briefly remind our listeners as to what malaria is and how we currently treat the disease.

WIRTH: Malaria is an infectious disease. It's caused by a microorganism that is carried by mosquitoes. And the disease that we know of as malaria, primarily, the symptoms are caused by the result of the parasite infecting the human's red blood cells. And the disease can be very severe, it can lead to coma and death, that could happen to anyone. But the burden of the disease is primarily in young children in Africa. So once the parasite has successfully infected the individual, that individual then can serve as a source of infection for new mosquitoes when they feed on the person, so then the cycle continues. Unlike many of the infectious diseases we've been hearing about recently, the COVID virus, for example, which is transmitted through airborne from person to person, this disease requires the mosquito as an intermediate host.

There are about 100 species of mosquito that can transmit human malaria. Mosquitos are responsible for more human deaths than any other animal on the planet. (Photo: Ryszard, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

O'NEILL: How is the world faring right now in the fight against malaria?

WIRTH: In many ways the world is making progress. In the first half of this century, we have seen reductions in overall burden of disease and reductions in death. And in some countries, we've actually seen malaria completely eliminated from those countries and WHO has declared countries as certified as malaria free. But in sub-Saharan Africa, progress over the first 15 years of this century was really quite successful, there was a reduction in overall malaria cases, and importantly, a reduction in the number of deaths. However, starting in around 2015, progress seemed to stall. Now, it's important when we say stall, that is the number of cases now and in 2015, are quite similar, and the number of deaths are quite similar. But that's of course, in a background of a growing population in sub-Saharan Africa. So, the current measures are still reducing malaria burden, but we're not making progress toward eliminating the disease, particularly in the high burden countries in Africa.

O'NEILL: Can you tell us a little bit more about this vaccine that's just been recommended by the World Health Organization?

A child dies from #malaria every two minutes.

— World Health Organization (WHO) (@WHO) October 6, 2021

One death is one too many.

???? Today, WHO recommends RTS,S, a groundbreaking malaria vaccine, to reduce child illness & deaths in areas with moderate and high malaria transmission https://t.co/xSk58nTIV1#VaccinesWork pic.twitter.com/mSECLtRhQs

WIRTH: This is the first ever vaccine for a human parasitic disease. Parasites are very complicated organisms, they have 5000 genes compared to say, a virus that has 10 or 20 genes. And it's been very hard to create vaccines that are able to impact the parasite's infection, or its ability to cause disease. So, this is a very exciting development.

O’NEILL: And what have been some of the steps in getting this vaccine developed and then approved?

WIRTH: It has been over 30, even 40 years in development, this particular vaccine, and it has gone through both standard clinical trials, both phase one, phase two and phase three clinical trials. The phase three clinical trial was in about 16,000 children in 11 sites in seven countries in Africa. And after the conclusion of this trial, there was a positive recommendation by the European Medicines Authority for the vaccine. However, the World Health Organization wanted to first test the feasibility of implementing this vaccine on a broad scale in Africa, particularly to children, the most susceptible group, and so the result of these implementation trials was the vaccine is indeed safe. Those safety signals seen in the phase three trial were by chance. It is feasible, the vaccine was implemented using an existing vaccine delivery program called the Expanded Program in Immunization, or the EPI program, which is implemented across the African continent and reaches very high levels of coverage, especially for a recently introduced vaccine. And the impact of vaccinating children was the overall 30% reduction in hospitalizations due to severe malaria, a reduction and, although the implementation studies didn't look at vaccine efficacy directly, there were reduced numbers of malaria cases in those children vaccinated. So the recommendation by the top committees at WHO that consider vaccines, and consider the malaria program and policies around malaria was in fact, to recommend the vaccine for broader use. Clearly, the vaccine is not ideal. It doesn't completely prevent infection, and it requires multiple doses. However, it is a completely different mechanism of preventing disease than existing measures, which include controlling the vector, so reduce essentially the mosquito's ability to get to and bite individuals, and diagnosis and treatment of clinical malaria, also very important in reducing disease burden, but different mechanisms. A vaccine actually teaches the human immune system to recognize the parasite as it enters the body and attack it. After vaccination, the person is poised to respond to infection rapidly, and thereby prevent the disease from manifesting itself.

A poster advertises a malaria vaccine clinic from a trial program in 2019. (Photo: GHTC, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

O'NEILL: Now, what issues, if any, might we see with the rollout of the vaccine now that it has been approved?

WIRTH: Well, I think one of the main issues of course, there's a lot of excitement, everyone will want the vaccine but in the first years, the supply will be limited because of course, until the vaccine was approved, the company and those providing funding for the vaccine weren't ready to make the investment. The Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations is the funding agency for vaccine purchase for many of the countries where malaria is endemic. So, the GAVI board now that WHO has made the recommendation, this will go before the GAVI board, and they will make a determination about whether or not they will invest in purchasing doses of the vaccine for countries to use. This is a very important step and it's not necessarily a foregone conclusion that GAVI will approve this. So, I think it's very important at this point, that countries and populations who want this vaccine let their views be known. GAVI has a broad base board, including board members from disease endemic countries, and I think it will be important to listen to those voices. But the vaccine interest and uptake among the families who were part of this 800,000 children in the implementation pilots were very enthusiastic about this opportunity for their children.

O'NEILL: What does this vaccine mean for other malaria vaccines and mean for vaccine science in general?

WIRTH: This work has proved that a vaccine for malaria is possible. There were many who didn't believe it was possible. And this also opens the door for innovation. We're already seeing potential new uses of this vaccine in preventing the major peak or seasonal peak of malaria infection in young children by providing a booster shot to those already vaccinated to give them a little extra protection during the peak of malaria transmission. There will need to be more evidence for final kind of regulatory recommendation, but its data is accumulating that this is a very clever use.

Immunologist Dyann Wirth is the Richard Pearson Strong Professor of Infectious Disease at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (Photo: Courtesy of Harvard T.H. School of Public Health)

There are other vaccines that are in the pipeline for development, some that are based on the same actual antigen molecule, but different formulations and presentations, which are in clinical trials. There's a whole cell vaccine. And excitingly, we heard very recently that the group in Germany, the company in Germany, BioNTech, that has been involved in the breakthrough COVID vaccine, actually is taking on a development project to develop an RNA-based malaria vaccine. Again, these are innovations. We don't know if they're going to work. But I think this gives a kind of validity to this strategy. And one that I think is, is both exciting, and I think will allow the scientific community to begin to imagine making even better vaccines. This first one is a groundbreaker. And it's, it's very important to say here that this represents years of work. It takes a village to raise the child. It takes a super village to make a vaccine.

CURWOOD: Dyann Wirth is an immunologist and Professor of Infectious Disease at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neil.

Related links:

- World Health Organization | “WHO Recommends Groundbreaking Malaria Vaccine for Children at Risk”

- More on Dyann Wirth

[MUSIC: Abdullah Ibrahim, “Soweto” on African Herbs, The Orchard Music]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Genevieve Santilli, Teresa Shi, Gabriell Urton, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth