Soil: The Story of a Black Mother's Garden

Air Date: Week of February 23, 2024

The cover of Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden. (Image: Courtesy of Simon & Schuster)

Over seven years poet Camille Dungy gradually transformed her sterile lawn in white Fort Collins, Colorado into a pollinator haven teeming with native plants and the wildlife they attract. Her book Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden recounts that journey alongside a world in turmoil amid the coronavirus pandemic, police violence and wildfires. Camille Dungy joined Host Steve Curwood to talk about how all her hard work amending hard clay soil has yielded gifts of joy as well as metaphors.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

We turn now to a fresh take of the genre of nature writing. Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden is mostly written in prose, but poet Camille Dungy says she couldn’t resist weaving in several poems to her book, including one called “Clearing.”

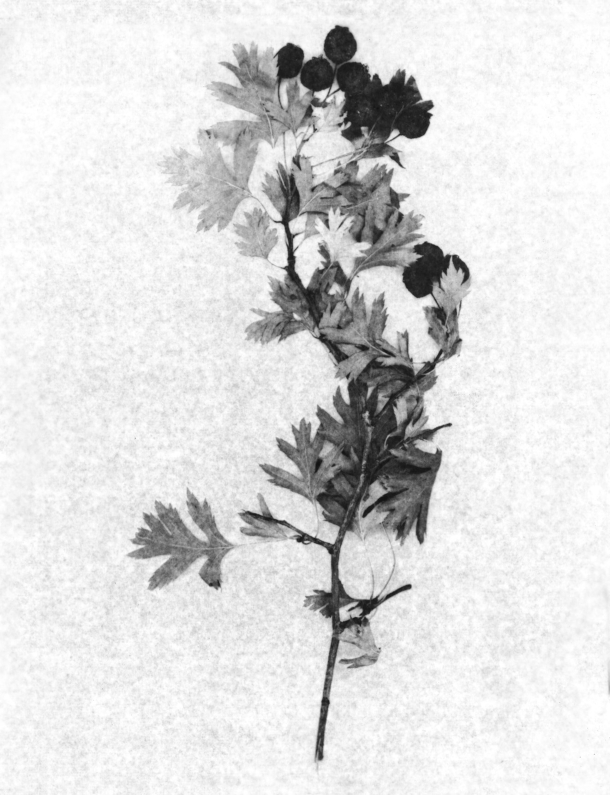

Hawthorn branch with berries. (Photo: Camille T. Dungy and Dionne Lee)

DUNGY:

all night the wind blows & my mind

my mind is like the hawthorn that loses

limbs they litter the ground crush

the black-eyed susan scatter buds

over rows of lettuce bean sprouts

whose greens are clusters of worry

in raised beds blown leaves & cracked limbs

threaten our foundation water backs up

in gutters seeps into the house’s walls

but my mind my mind is not in the house

in the yard’s far corner the eye of my mind rests

on a hawthorn branch shaken snapping

hectic then still the day dawns

without anger the blue jay I’ve looked for

pushes sky off his crest how splendid

his wings & tail it’s not so much

that before this he’d hidden himself

it’s only he favored a roost

I could not see until the storm thinned the tree

CURWOOD: Camille Dungy, reading a poem from her memoir Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden. It recounts her seven-year odyssey to diversify her plantings in the very white community of Fort Collins, Colorado. With a lot of grit and elbow grease, she transformed her sterile lawn into a pollinator haven teeming with native plants and the wildlife they attract. Camille Dungy is the poetry editor of Orion Magazine.

Camille Dungy is a University Distinguished Professor at Colorado State University and Poetry Editor of Orion Magazine. (Photo: Beowulf Sheehan)

DUNGY: This is not the book I thought I was writing. I thought I was writing a book that may, in fact, have aligned more closely with some of the conventions of nature writing I was raised in. And those are conventions that leave a lot of the people out. It's like, this kind of odd, really odd absence of mothers, of women who are mothers. And I was continuously confused by that absence. And I think with that sort of failure of imagination, where we haven't seen particular kinds of people, particular kinds of bodies, particular ethnicities, particular sort of genders, in those spaces, it erases the ability for those communities to be seen doing the work they are doing. My kind of environmental literary education of 19th and 20th century American nature writing suggested to me that the way to be a nature writer is to go out into the woods by yourself, and just look at things for a long time, and then write about it in incredible solitude. If that is the only way to engage with the world, with the greater than human world, with the natural world, most of us can't do it. Most of us do not have access to that kind of space and time. Most people do not have the ability to wander away from their families for days, months, years at a time. Most of us have to have a deeply interconnected, often urban or suburban sort of life. And you know what, you can still be deeply engaged with the greater than human world, you can be deeply engaged with your natural landscapes, and be living in a city, and be living in a suburb. And until we work on this aspect of the American imagination that has somehow been allowed to believe that nature always means out there, away, someplace far away, the catastrophic state of the planet cannot be amended. And I just feel like it's really, really important in my yard, to make a stand against that kind of destruction, and to make a space instead of welcome and connectivity and possibility.

Camille Dungy holding native flax blossoms. (Photo: Camille T. Dungy and Dionne Lee)

CURWOOD: At one point in your book, you write that -- let me see if I can get the quote right here -- "Whether a plot in a yard or pots in a window, every politically engaged person should have a garden." Which of course in part reflects your experience, because of the rules and regulations in your town and some of the politics, frankly, about setting up your yard the way you would like to have it. So is it fair to say that your garden was a bit of an act of revolution?

DUNGY: I think that that is fair to say; it's still oddly not as common to find native plantings in a lot of suburban developments. There's still a sense that the aesthetic of cleanliness and refinement does not include winter brown growth still left up in April. And so there's a way in which my yard looks unkept. And it looks kind of scraggly, and it's full of brown, and wild things that are often considered weeds, and a kind of rangy rowdiness.

CURWOOD: And it fits into a stereotype: if Black people move into the neighborhood, it's not gonna do so well.

A cluster of native flowers in the central plot of Camille Dungy’s yard (Photo: Camille T. Dungy and Dionne Lee)

DUNGY: Yeah, yeah. There are often preconceived notions about what Black people do to a neighborhood, what they do to your property values, how well they'll keep their house and their land. Which, since my family is the only all-Black family in our neighborhood, for me to then have that yard, which is that way because I'm using native plantings, because I'm using low-water processes, because I leave those winter things up a long time so that the overwintering beneficial insects have a safe space -- like there's a reason that I'm doing this, but that still doesn't fit this particular kind of cookie-cutter aesthetic. My town, Fort Collins, Colorado, has moved in the direction that I was already in. And so I'm lucky. But there are people all over the country who do end up with really severe fines for making these kinds of decisions, who come home and have their yards bulldozed by the city, right? That there's stakes for making these kinds of decisions in your yard.

CURWOOD: Well, I think at one point, you talk about getting fined for the appearance.

DUNGY: I did get fined. I had my green bin, my compost bin was visible. You can't have the compost bin visible, because that's not attractive to see that.

CURWOOD: Ooh, shocking! Very shocking. Oh, my goodness! But on a more serious note, with a range of acceptance, shall we say, from the Fort Collins community, you're also in the middle of America, and you're, well, actually, you're in the Front Range. Well, you talk about the trauma in your book. I mean, police violence, of course; you had fires coming down the hills towards you.

Thick smoke from the Cameron Peak Fire filled Fort Collins, Colorado in the fall of 2020, creating air too hazardous to garden in. (Photo: FarGah1, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DUNGY: Very close. They got, they got very close!

CURWOOD: Why was it important to you to include all of this alongside writing about your garden?

DUNGY: Yes. I wanted to write an honest portrayal of what it meant for me to try and build a more sustainable and diverse landscape around me from the ground up, right? That this was not just a frivolous act, this is something that really required digging in for me. And part of why this was sometimes not easy is that in the time that I'm trying to do this, all these other things that you're describing are happening, they can never be far from my mind. Sometimes I can't go out and garden because I couldn't breathe outside, the smoke was so bad that it was impossible to be outside. And yet, I am inside and I'm sheltered, and I'm relatively safe in that sense. But the sweet birds who nest in the big tree in our yard, they didn't get to get away from that. And so I'm watching them, trying to figure out how to cope with this human-caused catastrophe that is catastrophically disrupting their existence. I didn't think I could honestly describe the world that I was living, and the world that I was working to make better in my own little corner, right, without honestly and directly talking about the many traumas in the present, and this foundational history that were swirling around me all the time, are swirling around me all the time.

CURWOOD: Yeah, never an easy time. But even more challenging right now. Talk to me a little bit about the patience that all this required. Your garden was not exactly an instant project. At one point, it sounded like you could have used a jackhammer to get down through what was there.

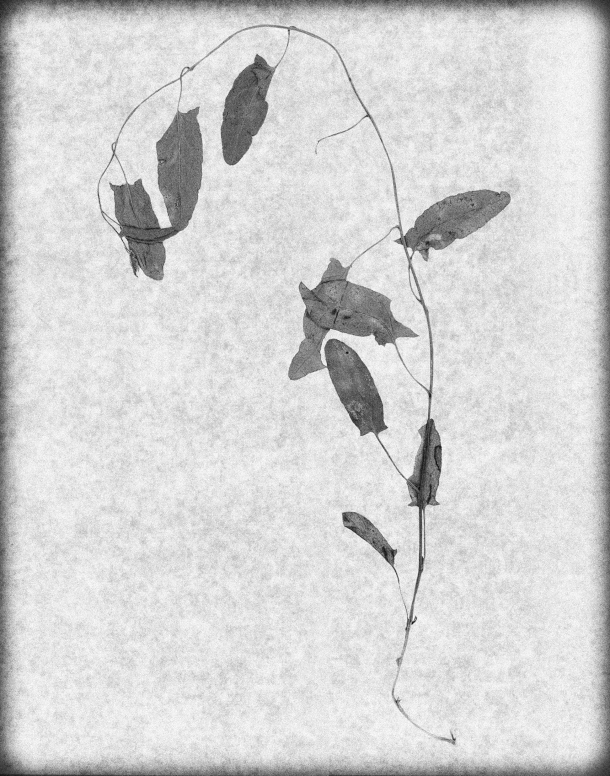

Bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis) (Photo: Camille T. Dungy and Dionne Lee)

DUNGY: Oh, the soil, the soil here can be miserable to work with. It's clay soil, so it's really, when it's dry, it's really, really dry. And what's left behind under heavy Kentucky bluegrass sod or the river rocks that were the other ways that this yard had been landscaped, hardscaped, like underneath that it was just compacted clay. Like, just hard, awful. And, yeah, I broke tools trying to get through it, it was tough. And the garden is never finished. I have a giant project that we're about to start actually next week. It's this ongoing process. And I think, again, returning to that question of why I think a politically engaged person should have a garden and also a clarifying note that when I'm talking about a politically engaged person, I'm thinking about anybody who has a vested interest in the decisions that we make as a culture towards how we want the future to look. And so that's what I mean when I say any political person. And the garden, because it's ongoing, because the process just continues and every year, there's things that have to be done again, and every day, during the height of growing season, there are particular kinds of insidious weeds I have to look for daily and pull out and deal with on a regular basis. That kind of constant care and constant attention reminds me that anything that matters will require that kind of constant care and attention. So anything that I want to do in the world, any place that I want to see more beauty in the world, or more diversity or more sustainability, I don't get to just do it once and be finished. I have to return. But here's the blessing that the garden also gives me. That peace, that quiet, that full, robust life, the beautiful smells, the sounds, all those lovely birds -- I get joy, and pleasure, and a kind of reciprocal grace from having done that work.

_(3105112704).jpeg)

Bindweed bears attractive flowers but chokes out other plants in the garden. (Photo: Phil Sellens, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: They say a weed, of course, is just a plant in the wrong place. But you had a lot of those, I think! Yeah, I think you tried some cardboard to see if you could bump them off. But those, those weeds, they, they are able to make their way up through everything. Talk to me about uprooting things that need to be removed and uprooted as a metaphor, really, for societal change.

DUNGY: I had already written a couple of responses to the 2016 elections, describing what happened in my house the day after the election, and then right after the inauguration. And I had written those pieces and they felt very important to me. But then I was out gardening and had to pluck some bindweed from around the stem of some native blue flax. And you have to do this process very carefully, because pull it out in the wrong way and it redistributes itself. And I realized that bindweed could work very well as a metaphor for the kind of noxious actions, behaviors and political courses that put my body and my family and so many people who I love and care about at great jeopardy. The thing about bindweed that's very interesting is that at first, it actually looks very lovely. It looks appealing and attractive and wonderful at first, and then it will kill anything that gets in its way.

Showy milkweed with a western honeybee. (Photo: Camille T. Dungy and Dionne Lee)

CURWOOD: Yes, bindweed is, it literally chokes things. It just chokes things, after looking so good.

DUNGY: And tears them down, right, and just pulls them down. And like, I say in the book that I end up trying to pay more attention to what I want to grow than what I don't. And in fostering and filling the space with as many beneficial plants as possible, I crowd out the noise, and allow more of the beauty and possibilities for variety to manifest.

CURWOOD: You know, it's funny, you get to play with your title "Soil," because, of course, it means transforming dirt into something that's productive with all the living organisms. But it's also a verb that we use to make something dirty. We say it's "soiled."

Smoke from the East Troublesome Fire towers over Fort Collins, Colorado, October 2020. (Photo: qurlyjoe, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DUNGY: I'm a poet, right? I mean, I trained as a poet, I love language. I love the multiplicity of language. And I love the ways that the same word has both. And then the one thing that I would say about soil that I find fascinating is that, you're right, like when something is degraded, we use the word soil, but also, when I'm thinking about why it was important for me in this book, even when I'm writing about the wonders and the splendors and the joy of my garden to include that, like, huge wildfire that we had, to include the COVID epidemic, to include the 2020 police violence and related uprisings, to also include those things -- good soil has absorbed and transformed rot and decay and feces and death, and it transforms those realities of the world into a material out of which new possibilities can grow. Until I acknowledge those realities and figure out how to absorb them into the soil of my being, there's no way for me to have fertile soil to grow imaginatively and personally.

CURWOOD: You’ve been listening to poet Camille Dungy talking about her memoir Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden.

Links

Find the book “Soil” (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

Watch the full video of our live event with Camille Dungy

Learn more about Camille Dungy and her books

Camille talks about the cover art and photographs in her book

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth