February 23, 2024

Air Date: February 23, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Flooded Out by Racism

View the page for this story

Dr. Robert Bullard continues to earn his moniker as the “father of environmental justice” by calling for justice for the community of Shiloh, Alabama. The area has suffered repeated flooding ever since a highway was widened and elevated in 2018, causing destruction to homes that Black landowners have proudly kept since the Reconstruction era. Dr. Bullard sat down with Host Steve Curwood to describe the trouble in Shiloh and how it’s affecting residents. They also take a wider look at environmental racism in America today and increasing vulnerabilities from climate change in the years to come. (19:14)

One Step Further: The Story of Katherine Johnson

View the page for this story

The 2021 children’s book One Step Further: My Story of Math, the Moon, and a Lifelong Mission tells the story of Katherine Johnson, an African American woman who while living under Jim Crow in the south worked at NASA as a mathematician and helped put a man on the moon. Host Steve Curwood spoke with one of Katherine’s three daughters, Katherine Moore, who co-authored One Step Further to help share her mother's story. (11:11)

Soil: The Story of a Black Mother's Garden

View the page for this story

Over seven years poet Camille Dungy gradually transformed her sterile lawn in white Fort Collins, Colorado into a pollinator haven teeming with native plants and the wildlife they attract. Her book Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden recounts that journey alongside a world in turmoil amid the coronavirus pandemic, police violence and wildfires. Camille Dungy joined Host Steve Curwood to talk about how all her hard work amending hard clay soil has yielded gifts of joy as well as metaphors. (16:51)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240223 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Robert Bullard, Camille Dungy, Katherine Moore

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

For Black History Month, Dr. Robert Bullard on how a highway put a Black community underwater.

BULLARD: Federal dollars are supposed to be used to bring about opportunity, to bring about mobility. It is not to destroy. And it's not just destroying the property and the houses for the people that are living today. You're talking about the theft of inheritance.

CURWOOD: Also, Katherine Johnson, the Black mathematician who helped put the first man on the moon.

MOORE: We say she was fearless. Because she didn't go into a job thinking, oh, she had to be subservient to the white engineers. She went in, “I know my math, they need me, I have a job to do.”

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Flooded Out by Racism

The highway drainage pipes let water out directly towards homes in Shiloh. Typically, drainage runs parallel to roadways to prevent such issues. (Photo: Lee Hedgepeth, Inside Climate News)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth.

I’m Steve Curwood. And today, we're celebrating Black History Month, starting with a man who has already made history and still is making it. Back in 1979, Robert Bullard was a freshly minted Ph.D. sociologist at Texas Southern University, researching segregated residential housing. One day his then-wife Linda McKeever Bullard came home to announce she had sued the state of Texas, Harris County, and the City of Houston. Her case cited civil rights laws to fight the siting of a municipal waste dump in the middle of a predominately black middle-class neighborhood. To back up her case, Professor Bullard used his skills with mapping and zip codes to document all five city dumps, and six of eight trash incinerators were located in Black communities, even though only 25 percent of Houston's population was Black. This was the first major case to apply civil rights laws in the fight against environmental racism, and it launched Dr. Bullard's career through the following decades, writing about and actively bringing to light eco-discrimination. Today, as the director of the Robert D. Bullard Center for Climate and Environmental Justice and a distinguished professor at Texas Southern University, Dr. Bullard is widely known as the father of environmental justice. But he's not resting on his laurels that include honorary degrees and many awards. Right now he is busy working on yet another case, and this one brought him to his roots in Coffee County, Alabama. Shiloh is just east of Elba, in Alabama, in an area that has been proudly kept by Black landowners since the Reconstruction era. But the widening and elevation of nearby Highway 84 has caused repeatedly destructive flooding for the past six years, with no signs of stopping. And now this disaster has become a personal mission.

I recently sat down with Dr. Bullard, and I asked him how he learned about the trouble in Shiloh.

BULLARD: I grew up in Elba, Alabama in the 50s. And I went to a segregated elementary, middle, and high school. And I grew up in a time when our streets weren't paved. We didn't have sidewalks, we didn't have indoor plumbing and sewer lines, etc. I left Alabama in 1968. And I hadn't been back to Alabama for any extended time. And so I got a call, and it was June of last year, from some of the people I had gone to school with, saying that, Bullard you need to come back to Elba, because there's a highway that's in Shiloh community, which is outside of the city, in Coffee County, in the rural area. This highway is now causing flooding in the community. The Alabama Department of Transportation elevated the highway, you know, 10, 15 feet high and placed the community in a bowl. And the drainage system, storm water is now pushing water into the community. And I said what? I knew Shiloh was flat, it was farmland. There was no elevated highways or anything like that. And so I told them, I said, as soon as I get through what I'm doing, I'll come. And so I went in July. And what did I see? It happened to be raining in July. And I went to the community in Shiloh. That highway was just standing tall over the community. And we were there for like 45 minutes standing and I was up to my ankles in water. I said this is, this is terrible. This had been going on since 2018.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about Shiloh, in Coffee County, Alabama. Please paint a picture for us, if you will. What's the community like there?

Professor Robert Bullard grew up in Elba, Alabama, which is in the same county as the Shiloh community. (Photo: Lee Hedgepeth, Inside Climate News)

BULLARD: Well, you know, Coffee County is part of the family of Black landowners. Like my family. My family has owned land in Elba, Alabama since 1875. And that land is still in our family. Well, in Shiloh, you also have landowners that have owned land since Reconstruction. And these landowners survived slavery, Jim Crow segregation, and this highway now, it's created a nightmare. And so you're talking about land that is now being flooded. This is not a flood zone, residents out there don't qualify for flood insurance. And so you're talking about an area that is rural with septic systems. And when you have a septic system that is overburdened with flood waters, you have major problems of sewer line backups in homes, that people's homes are sinking into the ground. And their foundations are cracking, their roofs, the whole infrastructure of these homes are cracking. You're talking about veterans, in some cases, who went back home, retired after spending 25, 30 years in the military. They went back to live out their remaining days in peace. It has created a nightmare. I wrote a book on Highway Robbery: Transportation Racism in 2023. If I had to write a book today, the cover of that book would be Shiloh. This is highway robbery.

CURWOOD: Wait, I'm scratching my head. Ordinarily, highway drainage pipes are parallel to the road. But in Shiloh, what, they're pointing directly at this part of the community?

BULLARD: You know, I'm no engineer. But this is not rocket science. If you look at the way that this highway was built, you take a level neighborhood that's flat, and then you elevate a highway, and then the law of gravity will send that water down into the community. And if you look at the damage that has been caused over the last six years that this has happened, you can see the drainage systems are pointed like cannons into the community. It's almost as if the state is saying, “We want you out of here. And if you don't leave, we're gonna drown you. We're gonna drive you out.” This is one of the worst cases of environmental racism that I have seen in the 40 years that I've worked on this. This is not an industry, this is not some corporate. This is government, where people pay taxes. And this is tax dollars that's been used to build an infrastructure that is creating a nightmare for the community. This is an area where you have a lot of retired people who are living on fixed incomes, who don't have $5,000, $10,000 to repair or to replace a septic system. This is where you have homeowners. They're now being threatened with their homeowners' insurance to be canceled. And the stress. Some of the folks are saying that it's almost like they've been in a war zone. PTSD, mental stress. The residents don't have the money to fix up their homes, to have them cleaned up when their bathrooms backup and the stuff is coming out. I just had a call today saying that the septic systems now are overflowing and now raw sewage is running into the yards. This is not safe. This is not sanitary. This is not healthy.

CURWOOD: So in a situation like this, people will go to court. What's happened down in Shiloh?

Detention ponds and makeshift ditches can remain full of several feet of water even days after a rainstorm. The deep ditches present safety risks, and the standing water increases chances of mosquito borne disease in the community. (Photo: Lee Hedgepeth, Inside Climate News)

BULLARD: Well, the residents filed a Title VI discrimination complaint with the Federal Highway Administration, and that investigation is still ongoing and it's been over a year, and they're still investigating and the community is patient. But while the Federal Highway Administration, the government is doing that investigation, it's getting worse and worse and worse. And not only the flooding, the community discovered that there's a pipeline, a gas pipeline that runs parallel to the highway. They didn't know anything about this until recent. And New Year's Eve, there was a gas leak from that pipeline that created a lot of concerns about the residents. There are no warning signs in terms of pipelines. And as it turns out, the gas company, Southeast Gas came out and replaced two pressure regulators. And both the flooding and the pipeline are controlled and are under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Transportation. So Secretary Pete Buttigieg is basically overseeing, and the community has asked Secretary Pete to come to Shiloh and visit and see exactly that this is not a good use of transportation dollars. Even though that road was built under the Trump administration, the community is saying that the Biden administration has the responsibility and the obligation to fix this now because of the billion dollars under the bipartisan infrastructure law. And under the billions of dollars that's under the Inflation Reduction Act. We want to see action now. This community has waited too long for justice, and justice delayed is justice denied. And this community is hurting every day that this problem goes unfixed.

CURWOOD: You suggest that perhaps this was intentional, the building up of this highway and having the drainage come into this community with the idea of perhaps pushing that community out. And this is the year 2024. This is not something from the era of Jim Crow. This is happening in this Black community. Why?

BULLARD: This is happening today because somehow this community is considered less than. It has not been given the same opportunities and the same kind of care that's taken with white communities that run along that highway. There were white families that were bought out, there were white businesses that were bought out. And then they were not given the same level of treatment. So if we talk about Jim Crow, or differential treatment, we're talking about the whole idea of being treated differently if you live on one side of the road, and that side of the road that you live on happens to be Black. Now that is black and white. That is something not made up. It's real. And if the Secretary of Department of Transportation come and visit, we would say to him, in person, “This is not what federal dollars are supposed to be used for.” The federal dollars are supposed to be used to bring about opportunity, to bring about mobility. It is not to destroy. And it's not just destroying the property and the houses for the people that are living today. You're talking about the death of inheritance. Most of the families that live out there, as I said before, can trace their heritage back over a hundred years in terms of when that land was given. And so the loss of wealth that's taken by that flood, and by so close to pipeline, we say that is highway robbery. It is theft of wealth. And we say that that is not how tax dollars should be spent.

[MUSIC: The Staple Singers, “Respect Yourself” on The Very Best Of The Staples Singers, Concord Music Group]

CURWOOD: We’ll be back after the break with more from our conversation with the father of environmental justice, Dr. Robert Bullard. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Louis Armstrong and His All Stars, "West End Blues" (Live 1955) on Ambassador Satch, Sony Music Entertainment]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

And we’re back with our Black History Month special we began with Dr. Robert Bullard, the father of environmental justice. The community of Shiloh, Alabama has been facing disastrous flooding for six years, thanks to a decision to elevate a nearby highway. That turned the flat neighborhood into a sort of geographic bowl, and homeowners have been unable to keep up with the continual damage to their homes and daily lives. Professor Bullard explains that this is only going to worsen with climate disruption.

Shiloh residents are also concerned about a nearby gas regulator, which leaked on New Year’s Day. (Photo: Lee Hedgepeth, Inside Climate News)

BULLARD: You know, climate change is a vulnerability accelerator. Climate change, like flooding, will increase in coming years. And so the fact that we now have a manmade flooding situation, in terms of this highway, it's only going to get worse. As I said, I've been to Shiloh in the last seven months, it's flooded three times that I've been there. And it's not just hurricanes that we're talking about, or tropical storms, we're talking about heavy rains, that the area's flooding. We're likely to see more and more flooding. This is not a floodplain, the area does not qualify for flood insurance. And so you're talking about a widening economic gap and a widening wealth gap in coming years because of the vulnerability and the geographic location of where they are.

CURWOOD: What's the solution? Some suggest a buyout of the people there, some suggest doing the engineering to move the risks of the pipeline, and the grading of the highway away from this community. What do you think should be done?

BULLARD: Well, I think the community should drive the solution, and the perpetrator of the problem should pay. It's like, we have a principle in the environmental justice movement. It's called the polluter pays principle. In this case, the person or the organization or the institution or the agencies that caused the problem should fix the problem, and compensate the communities for their loss and damage. Everything that was damaged, the community should be made whole. And for some residents who want to be bought out, I think that's their preference. But for those who want to stay, and want to maintain their lineage, they want to maintain their inheritance and want to keep that land being passed down from one generation to the next, unbroken, they should have that right. The highway department did not have the right to destroy this community, it does not have the right to continue to create harm for this community. So I think there has to be a solution with the city, the county, the state and the federal government. But the ultimate solution is to make this community and the homeowners whole. Property owners whole. And it's not just fix the highway and forget the people. The damage that has been caused in terms of people's homes, people's property that's damaged, the mental stress. I've talked to the residents and they are stressed out. They have lived six years of hell, their American dream has been turned into a nightmare. And whatever compensation, whatever mental health counseling or whatever that's needed, I think we bring in experts to talk about solutions to this problem in terms of how do we make this community whole. And to make sure that it never happens again.

The water carried into Shiloh is often polluted with litter and debris, which is then deposited on the residents’ land. (Photo: Lee Hedgepeth, Inside Climate News)

CURWOOD: Now, you're Robert Bullard, you're not just an ordinary advocate here. Many call you the father of environmental justice, you've written I believe, some 18 or more books about environmental racism. And by the way, you sit on something known as the White House Advisory Council on Environmental Justice. So you have direct access to the White House. What kind of response were you able to get at the national level to get this situation taken care of? I mean, another way of asking this question is, if Bob Bullard with his resume and his connections can't get this fixed, where could anything ever get fixed when it comes to environmental racism?

BULLARD: Well, you know, when 2024 came in, I said, I'm gonna make a New Year's resolution. It's something I don't usually do. But I said, I'm gonna make an exception. I said, 2024 will be the year that Shiloh gets justice. And I said if I can't get justice for Shiloh, I need to knock my name off of that, quote, "father of environmental justice." And I need to somehow resign from the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council. Because if this is not the example, this poster child for environmental racism, if we can't get justice, there needs to be some changes. And I think the idea, we're getting traction, we're getting into those rooms, there's consideration right now as we speak. And, you know, I'm not just a professor, but I'm also a Vietnam-era Marine Corps vet, oorah. We are relentless. We are like the Terminator. And I told the community when I came there in July of 2023, I will be back, laser-focused. And so we will get justice in 2024. This is Black History Month, and the fact that we need to highlight our history. We need to highlight our victories. But we also need to make history. We want to make history in 2024 by getting justice for Shiloh. Justice for these Black landowners that inherited land from their parents and grandparents that came out of Reconstruction. That is what we're talking about getting justice for.

Shiloh resident Willie Horstead Jr.'s home is sinking into the ground due to the extreme flooding. The sinking house has even caused his gas meter to rip through the home’s underpinning. (Photo: Lee Hedgepeth, Inside Climate News)

CURWOOD: Professor Bullard, why do you think environmental racism is still so pervasive in this country?

BULLARD: Well, you know, America is segregated, and so is pollution. And so are the vulnerabilities to climate. So are the vulnerabilities to where highways are built or infrastructure is built, I call it infrastructure apartheid. It's hard to unpack those centuries of history, and to get that out of our policymaking. And it's true in voting, civil rights, environmental protection, as well as issues around education. We have to dismantle those systems that create these inequalities. And we have to fight harder today because there are forces that are trying to take us back to literally the cotton fields, or trying to take away our right to vote or take away our right to education. And so we have to fight harder. And we have to understand that young people are more likely not to see these barriers that are artificially thrown in front of us. They want to move forward and move fast and furious. And I think climate change is one of those areas. As I said, I'm a Boomer, proud of it. Still fighting, still standing. But Millennials, Gen Xers and Gen Zers or Zoomers, they outnumber us. That new majority has to be given that platform to make those changes and dismantle this artificial system that create these separate and unequal opportunities and realities. That's the struggle. And that's the challenge of the future.

CURWOOD: Now, you've been working on environmental justice for virtually all of your career. What gives you hope, from all this work?

Professor Robert Bullard, nicknamed as the “father of environmental justice” has made getting justice for the Shiloh community a personal goal for 2024. (Photo: Dave Brenner, University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BULLARD: Well, what gives me hope is, we have come a long way. What keeps me going is the fact that we have generations of environmental justice scholars, activists, lawyers. I have students who have students who have students that are doing this work now. And when I started, there was no money, when President Clinton signed the executive order for environmental justice, February 11, 1994. And 30 years later, when President Biden signed the executive order on environmental justice, the day before Earth Day in 2023. Now we have an Inflation Reduction Act that has $60 billion, billion with a B, for environmental justice and another $60 billion for a clean energy transition. We have made a lot of progress. But in 2024, we still have Shiloh that's flooding. So we still have a hell of a lot of work. And a hell of a lot of convincing that these issues of structural and institutional racism that drive a lot of the environmental degradation, and even drive the vulnerability for climate change. In the coming years, flooding is going to be a major problem for the country. 25% increase in flood risk. But for communities of color and Black communities it's not 25%, it's 40%. So we need to concentrate on solving these problems, and making sure that we build vulnerability indices and deal with these communities that are at greater risk for climate and make sure that when we come up with solutions, they just don't somehow plan for the more affluent, but we have to plan for the most vulnerable. If we plan for standards, environmental standards that would protect children, the most vulnerable in our society, we protect everybody. When we place the most vulnerable at risk, we place everybody at risk. Going forward we have to make sure we put justice and environment justice and climate justice in housing, transportation, energy, and health. It's one movement now and that movement is about justice.

CURWOOD: Robert Bullard is a Distinguished Professor of Urban Planning and Environmental Policy at Texas Southern. Thank you so much for taking the time.

BULLARD: My pleasure. Thank you.

Related links:

- About Dr. Robert Bullard

- Inside Climate News | “How Racism Flooded Alabama’s Historically Black Shiloh Community.”

[MUSIC: The Staple Singers, “Respect Yourself” on The Very Best Of The Staples Singers, Concord Music Group]

One Step Further: The Story of Katherine Johnson

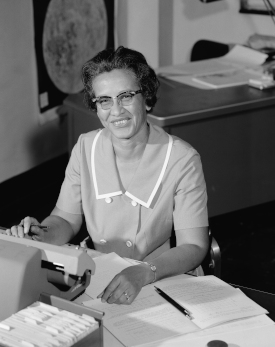

Katherine Johnson, watching the movie premiere of Hidden Figures on December 1, 2016. (Photo: Aubrey Gemignani, NASA, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: The compelling story of a mathematics genius who grew up as an African American girl during the era of Jim Crow shows the sky isn’t even the limit when one considers outer space. The 2021 graphic book for children called One Step Further: My Story of Math, the Moon, and a Lifelong Mission tells the story of Katherine Johnson. You may know that name as she was the NASA employee who did the hand calculations for many of America’s earliest manned space voyages and her story was featured in the movie Hidden Figures. One scene shows her as a child prodigy amazing a teacher:

YOUNG KATHERINE: If the product of two terms is zero, then common sense says at least one of the two terms has to be zero to start with. So, if you move all the terms over to one side, you can put the quadratics into a form that can be factored, allowing that side of the equation to equal zero. Once you’ve done that, it’s pretty straightforward from there.

TEACHER: In all my years of teaching, I’ve never seen a mind like the one your daughter has.

CURWOOD: Hidden Figures tells the story of three Black female mathematicians – Katherine Johnson and her colleagues Dorothy Vaughn and Mary Jackson, and their lives as they worked as human computers at NASA during the Space Race. The film earned three Academy Award nominations and several dozen awards after its release in 2016, and Katherine started to write her own autobiography and memoir. Katherine Johnson passed away in February of 2020 at the age of 101, leaving behind her pioneering legacy in astrophysics and three daughters. For our live book club event, we were joined by one of those daughters, Katherine Moore, named after her mother, who is also a coauthor of this picture book for children. Katherine Moore told us her mother showed signs of being a math genius even before she had begun school – around the time when a young child might be picking up this very picture book and reading about Katherine’s Johnson’s life. The story goes that the family was told by a neighbor that

MOORE: At four years old, she was walking up the street and they said, “Well, where are you going, little girl?” She said, “My brother is having trouble with math in school, and I'm going to help him.” She was the youngest. My grandfather did not stop her or make her go home. At four the friend of the grandmother said, I think I need to start a kindergarten class, she needs to be in school. And that's how it started.

CURWOOD: And Katherine Johnson passed down her fascination with numbers to her own children:

MOORE: And her love of numbers. She said, I just like numbers. They were fun. I counted the plates and the saucers and the steps to church. She counted everything; she really did. And I can remember as a child, we would ride in the car because that's how you traveled. And she'd say, all right, who can add up the numbers on the license plates the fastest. And we'd all do it. So, we were all good in math, because we had fun from the beginning.

CURWOOD: Katherine Johnson graduated high school at the age of 14 and enrolled at the historically Black university West Virginia State College, where her genius was recognized and nurtured. Later on for graduate school she was hand-picked to be one of three students to de-segregate West Virginia University in 1939.

Katherine Johnson at NASA in 1966. (Photo: NASA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

[MUSIC]

MOORE: She actually had a professor in college, W. W. Schieffelin Claytor was his name. And in those days, if you think about it, a lot of the teachers that were in our HBCUs, back in the 20s and 30s, were very frustrated doctors and lawyers and people that could not get jobs other than teaching other Black children. So, he was there. She was so good at math. He said, “You'd make a good research mathematician,” because that was his passion. But he never got to do what his passion was. And he said, “And if that's what your job is going to be, I'm gonna see that you're prepared.” So he wrote a course where she was the only student.

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Of course, Katherine Johnson was a Black woman in the Southern United States during the Jim Crow era. Her daughter recalled that old adage of Black people having to be “twice as good to get half as much” and says that was certainly true in Katherine’s case. But Katherine Johnson figured out how to finesse the racism she faced.

MOORE: You don't rock the boat; you just found another way to go around the boat. And I think what she taught us was, you can do what you have to do and stay in your lane. But the minute there's an opportunity, you take it. You don't have to be afraid. Because her father taught her, “Katherine, you're no better than anybody else. But nobody's better than you.” And that's how she lived her life.

[MUSIC]

MOORE: I know what the rules say, I don't have to agree with them. But they don't have to, you know, kill my spirit. I'm not gonna allow that. And they just worked around it. So, the times were hard, you know, there were rough spots. But that was not her way. Her way was just to do her job.

CURWOOD: Before there was NASA there was the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, where Katherine Johnson started working at the age of 35. She started off in the pool of Black women performing mathematical computations for the all-male, all-white flight research teams. In those days the human mathematicians were called computers.

MOORE: She went into the West Computers, the group of women. They would come every morning and say, “We have some engineers, they're looking for two mathematicians who can do A, B and C.” So this particular day, when they came, Dorothy Vaughn said, “Oh, I know just the girl for that job.” And that's how she got to the flight mechanics branch, which is where she ended up staying the rest of her 33 years at NASA. It was almost as if her steps were ordered, because she ended up in the right place at the right time for the right job.

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: And while Katherine Johnson had to fight at times to be acknowledged for her exceptional mind and math skills, she nevertheless played a critical role in some of the most important moments in the American space race. Her brain had to juggle analytic geometry, celestial mechanics and rocket science to compute trajectories for missions including the first spaceflight of Alan Shepherd, the first American astronaut in space, and the Apollo 11 voyage to the moon and back. Notably, before John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth, he personally requested she check the calculations for his flight.

Astronaut John H. Glenn Jr. entering the Mercury capsule “Friendship 7”. Before Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth, he asked for Katherine Johnson to personally check over the flight calculations to ensure they were correct. (Photo: NASA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

MOORE: You saw how Glenn was. He said, “Well, I don't know if I trust the computer.” He knew that there was a woman there who always did the math, and it was always accurate. He said, “If she says they're right, then I'll trust the computer,” because the computer had worked out what they needed. But he wanted to know that by hand, if she says they are right, then I'll go.

[SOUNDS FROM LAUNCH]

T MINUS TEN SECONDS, COUNTING. 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0. IGNITIONS, LIFTOFF. [ROCKETS FIRING]

CURWOOD: Katherine Johnson’s daughter was a college freshman that day.

MOORE: I was here at Bennett at the time. And that's when I really found out what it was she did. Because her picture was on the front page of the newspaper in March of 1962. And I looked down in the library, and I said, “That's my mother!” And when you read the article, it says, the headline said, “Lady mathematician at NASA gets man to space,” something like that. I have the picture framed somewhere. But the point I'm making is, the work was secret. She'd come home every day; she didn't bring anything home. But that important work was what she was doing.

CURWOOD: Katherine’ Johnson’s legacy continues to resonate to this day, and her name now appears everywhere from NASA’s Katherine Johnson Computational Research Facility to a spacecraft called the SS Katherine Johnson, launched in February 2021 to resupply the International Space Station. Also in 2021, for National Women’s Month, Katherine Johnson was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. We asked Katherine Moore about which of her mother’s honors she and her mother were most proud of:

Katherine Johnson, being awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama in 2015. (Photo: Bill Ingalls, NASA, Public Domain)

MOORE: I have to say the experiences of hearing what people think of her. It would be very difficult to choose, but I'll tell you how she felt when she got the invitation to go to the White House with President and Mrs. Obama. She said, “And he kissed me on my cheek!” Because she was able to go, it was just, it was a thrill of a lifetime. But she didn't do any of it for awards.

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Katherine Johnson’s story has been told many times over, in Hidden Figures, in her own autobiography and memoir, and now this children’s book. I asked Katherine Moore about the importance of sharing this story with children, especially the parts about her mother’s struggles as a woman working with a white all-male engineering team during Jim Crow, a decision made by the editors at National Geographic.

MOORE: I didn't even know about how it was going to turn out, because we didn't put it together this way. This is how they summarized her story. And I think it just played more into “in spite of” - you can be successful. You can dream dreams. You can teach people things, no matter what you look like. And I told my sister, I said, I never could have done this on my own, it would have just been, you know, tell her story and all. But they wanted to put it in perspective. And I just think it makes it that much more meaningful.

Two of Katherine Johnson’s daughters, and co-authors of One Step Further , Katherine Moore (left) and Joylette Hylick (center) at a NASA Black History Month program in February 2016. (Photo: Aubrey Gemignani, NASA, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: That’s Katherine Moore, on One Step Further: My Story of Math, the Moon, and a Lifelong Mission, the story of her mother, NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson.

Related links:

- Find the book “One Step Further” (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Katherine Johnson memoir: My Remarkable Journey

- More on Katherine Johnson at NASA’s website

- Space.com | “Katherine Johnson: Pioneering NASA Mathematician”

- The New York Times | “Katherine Johnson Dies at 101; Mathematician Broke Barriers at NASA”

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Coming up as we continue our Black History Month special – a poet’s garden teems with native life, diversity, and of course, metaphors. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Louis Armstrong and His All Stars, "Dardanella" (Live 1955) on Ambassador Satch, Sony Music Entertainment]

Soil: The Story of a Black Mother's Garden

The cover of Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden. (Image: Courtesy of Simon & Schuster)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

We turn now to a fresh take of the genre of nature writing. Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden is mostly written in prose, but poet Camille Dungy says she couldn’t resist weaving in several poems to her book, including one called “Clearing.”

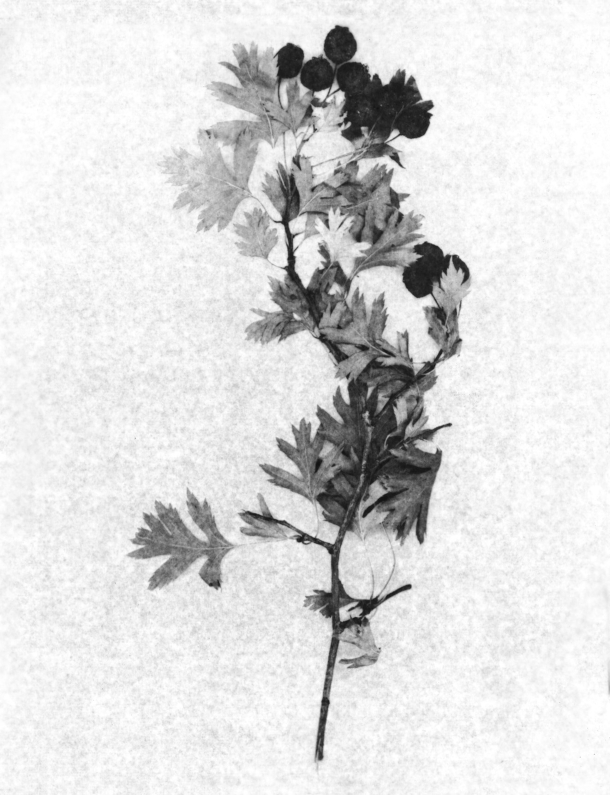

Hawthorn branch with berries. (Photo: Camille T. Dungy and Dionne Lee)

DUNGY:

all night the wind blows & my mind

my mind is like the hawthorn that loses

limbs they litter the ground crush

the black-eyed susan scatter buds

over rows of lettuce bean sprouts

whose greens are clusters of worry

in raised beds blown leaves & cracked limbs

threaten our foundation water backs up

in gutters seeps into the house’s walls

but my mind my mind is not in the house

in the yard’s far corner the eye of my mind rests

on a hawthorn branch shaken snapping

hectic then still the day dawns

without anger the blue jay I’ve looked for

pushes sky off his crest how splendid

his wings & tail it’s not so much

that before this he’d hidden himself

it’s only he favored a roost

I could not see until the storm thinned the tree

CURWOOD: Camille Dungy, reading a poem from her memoir Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden. It recounts her seven-year odyssey to diversify her plantings in the very white community of Fort Collins, Colorado. With a lot of grit and elbow grease, she transformed her sterile lawn into a pollinator haven teeming with native plants and the wildlife they attract. Camille Dungy is the poetry editor of Orion Magazine.

Camille Dungy is a University Distinguished Professor at Colorado State University and Poetry Editor of Orion Magazine. (Photo: Beowulf Sheehan)

DUNGY: This is not the book I thought I was writing. I thought I was writing a book that may, in fact, have aligned more closely with some of the conventions of nature writing I was raised in. And those are conventions that leave a lot of the people out. It's like, this kind of odd, really odd absence of mothers, of women who are mothers. And I was continuously confused by that absence. And I think with that sort of failure of imagination, where we haven't seen particular kinds of people, particular kinds of bodies, particular ethnicities, particular sort of genders, in those spaces, it erases the ability for those communities to be seen doing the work they are doing. My kind of environmental literary education of 19th and 20th century American nature writing suggested to me that the way to be a nature writer is to go out into the woods by yourself, and just look at things for a long time, and then write about it in incredible solitude. If that is the only way to engage with the world, with the greater than human world, with the natural world, most of us can't do it. Most of us do not have access to that kind of space and time. Most people do not have the ability to wander away from their families for days, months, years at a time. Most of us have to have a deeply interconnected, often urban or suburban sort of life. And you know what, you can still be deeply engaged with the greater than human world, you can be deeply engaged with your natural landscapes, and be living in a city, and be living in a suburb. And until we work on this aspect of the American imagination that has somehow been allowed to believe that nature always means out there, away, someplace far away, the catastrophic state of the planet cannot be amended. And I just feel like it's really, really important in my yard, to make a stand against that kind of destruction, and to make a space instead of welcome and connectivity and possibility.

Camille Dungy holding native flax blossoms. (Photo: Camille T. Dungy and Dionne Lee)

CURWOOD: At one point in your book, you write that -- let me see if I can get the quote right here -- "Whether a plot in a yard or pots in a window, every politically engaged person should have a garden." Which of course in part reflects your experience, because of the rules and regulations in your town and some of the politics, frankly, about setting up your yard the way you would like to have it. So is it fair to say that your garden was a bit of an act of revolution?

DUNGY: I think that that is fair to say; it's still oddly not as common to find native plantings in a lot of suburban developments. There's still a sense that the aesthetic of cleanliness and refinement does not include winter brown growth still left up in April. And so there's a way in which my yard looks unkept. And it looks kind of scraggly, and it's full of brown, and wild things that are often considered weeds, and a kind of rangy rowdiness.

CURWOOD: And it fits into a stereotype: if Black people move into the neighborhood, it's not gonna do so well.

A cluster of native flowers in the central plot of Camille Dungy’s yard (Photo: Camille T. Dungy and Dionne Lee)

DUNGY: Yeah, yeah. There are often preconceived notions about what Black people do to a neighborhood, what they do to your property values, how well they'll keep their house and their land. Which, since my family is the only all-Black family in our neighborhood, for me to then have that yard, which is that way because I'm using native plantings, because I'm using low-water processes, because I leave those winter things up a long time so that the overwintering beneficial insects have a safe space -- like there's a reason that I'm doing this, but that still doesn't fit this particular kind of cookie-cutter aesthetic. My town, Fort Collins, Colorado, has moved in the direction that I was already in. And so I'm lucky. But there are people all over the country who do end up with really severe fines for making these kinds of decisions, who come home and have their yards bulldozed by the city, right? That there's stakes for making these kinds of decisions in your yard.

CURWOOD: Well, I think at one point, you talk about getting fined for the appearance.

DUNGY: I did get fined. I had my green bin, my compost bin was visible. You can't have the compost bin visible, because that's not attractive to see that.

CURWOOD: Ooh, shocking! Very shocking. Oh, my goodness! But on a more serious note, with a range of acceptance, shall we say, from the Fort Collins community, you're also in the middle of America, and you're, well, actually, you're in the Front Range. Well, you talk about the trauma in your book. I mean, police violence, of course; you had fires coming down the hills towards you.

Thick smoke from the Cameron Peak Fire filled Fort Collins, Colorado in the fall of 2020, creating air too hazardous to garden in. (Photo: FarGah1, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DUNGY: Very close. They got, they got very close!

CURWOOD: Why was it important to you to include all of this alongside writing about your garden?

DUNGY: Yes. I wanted to write an honest portrayal of what it meant for me to try and build a more sustainable and diverse landscape around me from the ground up, right? That this was not just a frivolous act, this is something that really required digging in for me. And part of why this was sometimes not easy is that in the time that I'm trying to do this, all these other things that you're describing are happening, they can never be far from my mind. Sometimes I can't go out and garden because I couldn't breathe outside, the smoke was so bad that it was impossible to be outside. And yet, I am inside and I'm sheltered, and I'm relatively safe in that sense. But the sweet birds who nest in the big tree in our yard, they didn't get to get away from that. And so I'm watching them, trying to figure out how to cope with this human-caused catastrophe that is catastrophically disrupting their existence. I didn't think I could honestly describe the world that I was living, and the world that I was working to make better in my own little corner, right, without honestly and directly talking about the many traumas in the present, and this foundational history that were swirling around me all the time, are swirling around me all the time.

CURWOOD: Yeah, never an easy time. But even more challenging right now. Talk to me a little bit about the patience that all this required. Your garden was not exactly an instant project. At one point, it sounded like you could have used a jackhammer to get down through what was there.

Bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis) (Photo: Camille T. Dungy and Dionne Lee)

DUNGY: Oh, the soil, the soil here can be miserable to work with. It's clay soil, so it's really, when it's dry, it's really, really dry. And what's left behind under heavy Kentucky bluegrass sod or the river rocks that were the other ways that this yard had been landscaped, hardscaped, like underneath that it was just compacted clay. Like, just hard, awful. And, yeah, I broke tools trying to get through it, it was tough. And the garden is never finished. I have a giant project that we're about to start actually next week. It's this ongoing process. And I think, again, returning to that question of why I think a politically engaged person should have a garden and also a clarifying note that when I'm talking about a politically engaged person, I'm thinking about anybody who has a vested interest in the decisions that we make as a culture towards how we want the future to look. And so that's what I mean when I say any political person. And the garden, because it's ongoing, because the process just continues and every year, there's things that have to be done again, and every day, during the height of growing season, there are particular kinds of insidious weeds I have to look for daily and pull out and deal with on a regular basis. That kind of constant care and constant attention reminds me that anything that matters will require that kind of constant care and attention. So anything that I want to do in the world, any place that I want to see more beauty in the world, or more diversity or more sustainability, I don't get to just do it once and be finished. I have to return. But here's the blessing that the garden also gives me. That peace, that quiet, that full, robust life, the beautiful smells, the sounds, all those lovely birds -- I get joy, and pleasure, and a kind of reciprocal grace from having done that work.

_(3105112704).jpeg)

Bindweed bears attractive flowers but chokes out other plants in the garden. (Photo: Phil Sellens, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: They say a weed, of course, is just a plant in the wrong place. But you had a lot of those, I think! Yeah, I think you tried some cardboard to see if you could bump them off. But those, those weeds, they, they are able to make their way up through everything. Talk to me about uprooting things that need to be removed and uprooted as a metaphor, really, for societal change.

DUNGY: I had already written a couple of responses to the 2016 elections, describing what happened in my house the day after the election, and then right after the inauguration. And I had written those pieces and they felt very important to me. But then I was out gardening and had to pluck some bindweed from around the stem of some native blue flax. And you have to do this process very carefully, because pull it out in the wrong way and it redistributes itself. And I realized that bindweed could work very well as a metaphor for the kind of noxious actions, behaviors and political courses that put my body and my family and so many people who I love and care about at great jeopardy. The thing about bindweed that's very interesting is that at first, it actually looks very lovely. It looks appealing and attractive and wonderful at first, and then it will kill anything that gets in its way.

Showy milkweed with a western honeybee. (Photo: Camille T. Dungy and Dionne Lee)

CURWOOD: Yes, bindweed is, it literally chokes things. It just chokes things, after looking so good.

DUNGY: And tears them down, right, and just pulls them down. And like, I say in the book that I end up trying to pay more attention to what I want to grow than what I don't. And in fostering and filling the space with as many beneficial plants as possible, I crowd out the noise, and allow more of the beauty and possibilities for variety to manifest.

CURWOOD: You know, it's funny, you get to play with your title "Soil," because, of course, it means transforming dirt into something that's productive with all the living organisms. But it's also a verb that we use to make something dirty. We say it's "soiled."

Smoke from the East Troublesome Fire towers over Fort Collins, Colorado, October 2020. (Photo: qurlyjoe, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DUNGY: I'm a poet, right? I mean, I trained as a poet, I love language. I love the multiplicity of language. And I love the ways that the same word has both. And then the one thing that I would say about soil that I find fascinating is that, you're right, like when something is degraded, we use the word soil, but also, when I'm thinking about why it was important for me in this book, even when I'm writing about the wonders and the splendors and the joy of my garden to include that, like, huge wildfire that we had, to include the COVID epidemic, to include the 2020 police violence and related uprisings, to also include those things -- good soil has absorbed and transformed rot and decay and feces and death, and it transforms those realities of the world into a material out of which new possibilities can grow. Until I acknowledge those realities and figure out how to absorb them into the soil of my being, there's no way for me to have fertile soil to grow imaginatively and personally.

CURWOOD: You’ve been listening to poet Camille Dungy talking about her memoir Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden.

Related links:

- Find the book “Soil” (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Watch the full video of our live event with Camille Dungy

- Learn more about Camille Dungy and her books

- Camille talks about the cover art and photographs in her book

[MUSIC: Buddy Guy, “The World Needs Love” on The Blues Don’t Lie, RCA Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Quentin Bell, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mattie Hibbs, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth