Migrations: A Powerful Novel About A World Losing Life

Air Date: Week of April 5, 2024

The Arctic tern has the longest migration route out of any bird. Every year, it flies from the Arctic to the Antarctic and back. (Photo: Ed Dunens, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

In the 2020 novel Migrations set in the future, polar bears are extinct. So are chimpanzees and wolves and big cats. For the novel’s protagonist, this mass extinction is personal. So, she does the first thing that comes to mind: she makes her way onto a fishing boat to follow what might be the very last migration of the Arctic Tern from pole to pole. Host Steve Curwood speaks with author Charlotte McConaghy about her masterful debut work of environmental fiction.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

With summer just around the corner you might be starting to dream of books to add to your reading list, and if you like fiction we’ve got a true standout to suggest. The novel Migrations by Charlotte McConaghy uses beautiful prose to explore the core theme of climate disruption. Migrations is set in a future in which many of the animals we know and love, like polar bears and the great apes are extinct and the oceans are running out of fish. Yet, the Arctic Tern, a bird known for having the world’s longest migration, remains. In years yet to come one woman follows what might be the very last migration of Arctic Terns from pole to pole. But this work of fiction is about a voyage of discovery far beyond the birds. Charlotte McConaghy joined me back in 2020 from her home in Australia and I asked her to start by reflecting on what inspired her to write Migrations.

MCCONAGHY: Well, it's tricky for me to pinpoint it because it was one of those things that came in a lot of different pieces. It was quite fragmented. But I wanted to engage with my kind of concern around the climate crisis. But I didn't know how, because it felt just far too big. So, I sort of parked that notion. And I went traveling, and I wanted to explore the UK, which is where my ancestors are from. And I started noticing all the beautiful birds, the migrating birds over there, particularly the graylag geese, which I learned about while I was in Iceland. And I just became really fascinated with where they must be flying and these incredible journeys that were going on. And I started thinking about the idea that wouldn't it be amazing if we could follow them and experience those, those migrations with them? So, I think that's where that initial spark of an idea of this woman who's following the last migration of the Arctic tern.

CURWOOD: So, tell me, I mean, of all the animals on this planet, why the Arctic tern?

MCCONAGHY: Well, I didn't know initially, which bird she would be following. So, I did, I was doing a lot of research into a lot of different birds. And the moment I came across the Arctic tern, I knew it was the one - I fell in love with it. It has the longest migration of any animal in the world, from the Arctic to the Antarctic, and then back again within a year. And because it lives for about 30 years, over the course of its lifespan, it will fly the equivalent distance of to the moon and back three times, which I just thought was absolutely beautiful and kind of amazing that such tiny creatures could go so far for survival, and we're making this journey more difficult for them every year. So, they sort of became a metaphor for courage, the courage that Franny would need to take on her journey, and I think she takes a lot apart from them. If they can do it, then she can, too.

CURWOOD: So recently, we've been learning quite a lot about the emotional toll that climate anxiety and climate grief have for so many of us. How do you think this affects Franny, the protagonist of your novel?

MCCONAGHY: Quite severely. I think one of the reasons that I wanted her to be such a migratory creature herself, and such a wild creature, and so similar to the animals that she loves, is because I wanted her to have a really deep connection to the natural world, which would allow her to be a great mouthpiece for her to experience the loss of this wildlife and the natural world that's disappearing piece by piece, just as we're losing it. I think she suffers that grief, perhaps more intensely than the rest of us do, which is why she's so driven to do something about it.

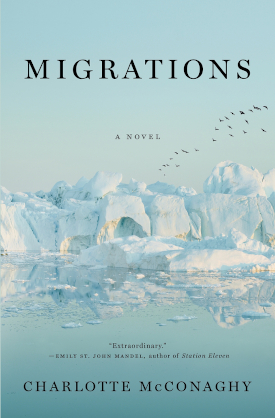

Migrations tells the story of one woman who wants more than anything to follow what might be the very last migration of the Arctic tern. (Image: Flatiron Books)

CURWOOD: Yeah, she's willing to risk her life to follow this passion.

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, that's right.

CURWOOD: One might say in some respects, climate change is perhaps changing everything. I mean, it just has so many impacts on the way that we're living now. But your character Franny is looking at the human aspects on the climate largely through their effects on animals. So, what is it do you think about animals that so resonates with Franny?

MCCONAGHY: I think, I think because she grew up without a family, she made a family of the wild creatures around her and the natural spaces. So, they became a kind of home for her when she didn't have a normal home. And they became her loved ones when she didn't have anyone else to cling to. And so, I think a big part of her is bound to these creatures. And I think also one of the things that originally was an inspiration for me was growing up, I really loved Celtic mythology and the myth of the Selkie, which is the story of seals that can shed their seal skin and become humans. And they can, the tragedy of the selkie is that they can fall in love and get married and have children, but they'll always be bound to the ocean. And this is something that kind of plays into Franny and her character. She says, at one point in the book, it's not fair to be a creature who is able to love but unable to stay. And so, I think that that is also part of her creaturely-ness, and this idea that she's not, she doesn't subscribe to a lot of societal values. She has no ambition. She doesn't want wealth. She is really just living in the moment, in a way that I think we all would love to be able to.

CURWOOD: Mm hmm. And she loves water, or she certainly spends a lot of time in and around and above water.

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, she absolutely does. And I think that's another element of that selkie myth coming in. I've always loved the ocean, there's something very mysterious and frightening and wonderful about it. I guess it's the most important part of our planet, really, because we're the only planet that has ocean which makes it a habitable planet for us. So, there's something kind of immense and important about the ocean. I hate the idea of it being pillaged for our benefit.

CURWOOD: And of course, Franny's quite concerned about, shall we say, overfishing?

MCCONAGHY: She is. Absolutely, yeah, it's a real problem for us. And in the world of the book, it's even more of a problem. And so, there's that terrible conflict for her that she has to talk her way onto a fishing boat. And it's the only way that she's going to be able to fulfill her journey. But it's sort of really gets under her skin. She hates it because she's so anti fishing. But I think that's one of the things that this book is about it. It's about overcoming our judgement of the other side of this as this big schism in the world, I think, between conservation and fishing and farming. And, and one of the things that this book, I think, is trying to say is that we need to be able to communicate and not judge each other in order to understand each other and actually try to find ways to support each other to move beyond the employment the way it is now and make it sustainable for the future.

CURWOOD: In other words, we're all in this thing together.

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, that's exactly right. Yep.

CURWOOD: So I guess it was Camus, who said, if you want to be a philosopher, write novels, maybe you took that to heart because at one point, you start, you have this discussion about whether people should work to save, quote, important animals, the ones that benefit societies versus working to save everything that seems to be slipping away from our ecosystem. And Franny is not happy that people would even think about making this choice. I think she says, and let me quote here, it's page 209: "What of the animals that exist purely to exist because millions of years of evolution have carved them into miraculous being?" So, talk to me about this discussion and why you decided to include it in this book.

A baby Arctic tern. (Photo: Gregory Smith, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, I think this really strikes to the heart of what the book is about, actually. It really upset me to think about the fact that in a dire future, we would only be focused on saving the animals that provide us with some measure of survival, the ones who offer us something. So, at this conservation base in the book, they're putting most of their resources into saving the pollinators because they're an integral to our food sources. But yeah, as you read, Franny voices something that I found really tragic myself and I struggle. I know that there's practicalities that need to be taken into account, but it seems immensely unfair, the tragedy of leaving all the rest of the animals to go extinct. You know, it's not their fault that they can't survive. It's our fault. And I think I realized that by writing this book, I was trying to remove humans from the center of all things, trying to point out that we are not the only creatures on this planet that have a right to be here and that deserve survival. And we shouldn't be behaving as though we are. I think, in a way, it's a love letter to animals, not because of what they offer us. But just because they're beautiful in their own right. And we would have a much poorer world without them. Biodiversity is key, but on a purely emotional level, we will have such immense loss if we let go of the animals.

CURWOOD: It makes me wonder if they could get together and let us go, would they make that choice?

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, I think they would if they could, although there are a lot more compassionate than we are, I think.

CURWOOD: In that same section of your story, you also have a scientist saying that birds should be contained and stopped from migrating as a way to save them. And yet, the husband of your main character here claims that migration is well, it's just part of being a bird. Talk to us about these dueling ideas and how this discussion made it into the book.

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, well, this was me trying to put myself in the headspace of the scientists and conservationists who are having to figure out how to save these animals, and really trying to imagine what we need to be doing. What do you do if you have an animal that is instinct bound to go on this epic migration in order to find food and breeding grounds, but the journey itself isn't survivable for them? Do you contain them to feed them and keep them alive? Do you force them to adapt? Or, is our involvement in their existence part of the problem that got us into this mess in the first place? Are we having too much of an impact on them? And should we just leave them alone? I don't really know what the answer is. And I think it's clear in the book because there's this ongoing discussion. I do think it's crucial for us to save critically endangered animals from the planet that we made too hard for them. You know, that's the least we can do. But there's something that sits very wrong for me in trying to change their fundamental natures, and the instincts that have led them through those millions of years of evolution. I find it heartbreaking thinking of caging birds.

CURWOOD: And don't imagine you think much of zoos then.

MCCONAGHY: I struggle with zoos, I don't like them. I like it when they use their resources for conservation efforts. But I don't visit them because I find it too sad.

CURWOOD: So, the title of your book is Migrations. So, what does the theme of migration mean for you in writing this book?

MCCONAGHY: Well, it was initially just about the birds. As I said, I was traveling around the UK and looking for a sense of roots and history and belonging. And I became fascinated with the gorgeous birds that I could see. I think I was fascinated with the idea of movement for survival, and what that might mean for humans, because it often means the same for humans. But I wanted to explore a character who had a kind of driving force inside her, and instinct like the birds for movement as survival, and yet, it was more of an emotional survival than a physical one. And I knew that pretty quickly, the kind of woman who would follow these birds would have to be a fairly special person, she started to form into this wild creature in my mind, who never stops moving, always roaming. And this impacts her relationships quite badly. But it's a compulsion of sorts like it is for the animals, she's searching for where she belongs. And I guess that kind of started bringing up the idea of people who don't know where they belong. And that can certainly be true of settler societies and migrant families, they can often feel a bit rootless, I think. Franny is kind of straddling these two worlds, one that belongs to the people who stayed and abound to their homes, and then one that belongs to the people who left, and perhaps maybe lost that sense of home. I think that's the complexity of migration for people.

Charlotte McConaghy is the author of Migrations. She lives in Sydney, Australia. (Photo: Emma Daniels)

CURWOOD: Now, your story has a lot of destruction, a lot of loneliness. And the impact of human activities is apparent on many of the pages of this book. Yet, somehow, it's fair to come away from it with a sense of hope. So, talk to me about hope and, and how is it that you're able to cast a spell of hope in such a dark tale as this one.

MCCONAGHY: It wasn't easy to be honest. I'm an optimist at heart. I couldn't live if I didn't think there was hope. But all joy in life would be gone for me. But writing this was one of the most difficult things I've ever done, it took me to some very dark places, and I often felt lost in them. So, I would stop, and I'd go outside. And I think even without realizing it, I'd be taking nourishment from the little pieces of the natural world around me that I could find, the birds that I spotted walking in trees, even if there are only a few. I'm city bound, so it was not always easy to find these little pockets of wildness. But you can do it if you're looking for them. And I read a lot of Mary Oliver poetry, which is all about our connection to nature and how it can feed our souls. And that would kind of inspire me to look around and see the truth of the fact that there's so much we haven't yet lost. That's what kept me going. I think we're saturated by bad news these days. It comes at us from every angle, and it's easy to become apathetic or to give up. But now is not the time to give up. It's the opposite. It's the time to fight. And it was really important to me that this book be about hope more than anything, because hope is energizing, it leads to action. And that's what we really need. I think in some ways, the book is a battle cry, and it’s reminding myself of that is how I kept going because I was able to see that there's hope everywhere. It's in the kindness and the generosity that we show each other every day. That's the real stuff. And I think that's what we need to be feeding.

CURWOOD: Charlotte McConaghy is the author of the novel Migrations. Charlotte thanks so much for taking time with us today.

MCCONAGHY: Thank you so much for having me. It's been lovely to chat.

Links

Migrations by Charlotte McConaghy

Purchase Migrations and support both Living on Earth and local bookshops

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth