April 5, 2024

Air Date: April 5, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Ohio Senate Race and Climate

/ Dan GearinoView the page for this story

The razor-thin majority Democrats hold in the Senate could be crucial to passing more climate legislation under a second term for President Biden, and in the event former President Trump is re-elected, could prevent the total unraveling of President Biden’s climate agenda. One of the key Senate races to watch in 2024 is the Ohio contest between incumbent Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown and Trump-endorsed Republican Bernie Moreno. Inside Climate News reporter Dan Gearino talks with Host Steve Curwood about the candidates and how electric vehicles and agriculture factor into the politics of this race. (14:39)

Land Back for the Yurok Tribe

View the page for this story

On the northern California coast the Yurok tribe is getting 125 acres of its stolen land back thanks to an historic partnership between the National Park Service, California State Parks, and Save the Redwoods League. Chairman of the Yurok Tribe Joseph L James joins Host Jenni Doering to describe how the land will help nurture Yurok cultural traditions. (09:43)

The Little Gods of the Forest

/ Major JacksonView the page for this story

Poet Major Jackson joins Host Jenni Doering to read his poem, “The Body’s Uncontested Need to Devour, An Explanation” and reflect about forest bathing and immersing ourselves in nature as a vital life-giving experience. (03:02)

From the History Books

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In their look back in history Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood celebrate the birthday of Everglades protector Marjory Stoneman Douglas. They also mark the debut of prepared frozen meals marketed as TV dinners. (03:10)

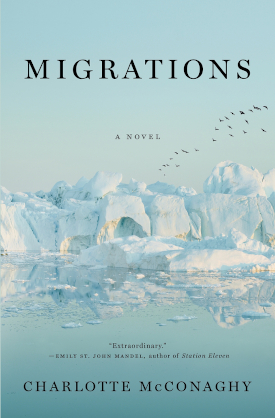

Migrations: A Powerful Novel About A World Losing Life

View the page for this story

In the 2020 novel Migrations set in the future, polar bears are extinct. So are chimpanzees and wolves and big cats. For the novel’s protagonist, this mass extinction is personal. So, she does the first thing that comes to mind: she makes her way onto a fishing boat to follow what might be the very last migration of the Arctic Tern from pole to pole. Host Steve Curwood speaks with author Charlotte McConaghy about her masterful debut work of environmental fiction. (15:42)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240405 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Dan Gearino, Major Jackson, Joseph L James, Charlotte McConaghy

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

The battle for a seat from Ohio could determine which party controls the US Senate…

GEARINO: This race is incredibly important for having the ability to pass additional climate and clean energy legislation or also having the ability to stop a President Trump from unraveling some of that legislation that's already been passed.

CURWOOD: Also, native Americans win back stolen land in California …

JAMES: It means healing. Healing for myself, healing for our people, knowing how far we have come as indigenous people, knowing our people had to get sent to boarding schools, knowing their language at one point trying to wipe our language away. And when I see this piece of property and a village coming back with the Yurok ancestral territory, it makes my heart feel good.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Ohio Senate Race and Climate

Prior to the 2016 election of Donald Trump, Ohio had been seen as a swing state for many years. (Photo: Tim Ide, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Voters in 2024 will not only choose who lives in the White House, but will also decide which party controls the Senate, with its unique powers to advance or block legislation and also approve or reject the appointments of judges and other high officials. Ohio is pivotal in the fight for Senate control, and after a hotly contested primary Republicans have chosen Bernie Moreno, a former car dealer who has closely aligned himself with 45th President Donald Trump. In November Mr. Moreno will face Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown. Speaking on MSNBC Senator Brown said that after already electing him three times to the Senate, Ohio voters know his record, and also know why they shouldn’t vote for his opponent.

BROWN: Well, they know that Bernie Moreno likes to look out for himself. I mean, he said in this campaign that he won't work with Democrats, he just is going to go to Washington and do his own thing. He's illustrated that by again, calling for a national abortion ban, with no exceptions, even though Ohio overwhelmingly last November, voted by 13 points for constitutional amendment on abortion rights, and the arrogance of he doesn't really care what the voters want. That's really who he is. And we will make that contrast of “I fight for Ohio. I listen to people. I do roundtables all over the state.” That's how we got a good infrastructure bill. That's how we got the chips bill. It's gonna create 1000s of jobs in Ohio. That's how you do this job.

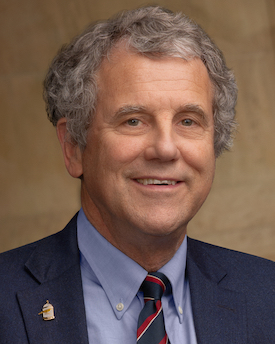

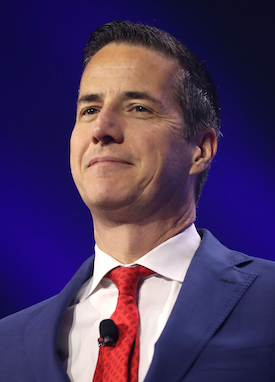

Ohio Democrat Sherrod Brown is seeking his fourth term as United States Senator in 2024. (Photo: Rebecca Hammel, U.S. Senate Photographic Services, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

CURWOOD: In his primary night victory speech, Mr. Moreno rejected the notion that Senator Brown knows what’s good for Ohio.

MORENO: He says he advocates for working class Americans. So, let's dissect that for a second. Under Sherrod Browns watch. China has gone from a $4 billion trade deficit to a $235 billion year trade deficit with America. The middle class in his country has shrunk under his watch. We've lost factory after factory under his watch. This is a guy who is for unfettered immigration. He is an open borders radical. What does that do? Who does that hurt? It hurts the very people he pretends to help. These are people who are getting crushed every single day at the grocery store, at the gas station. He's all for this green New Deal. This idea that all of us should drive an electric car, have whatever stove he tells us to, live in some small hut somewhere. While, of course, he hangs out with his buddies in Martha's Vineyard. That's who Sherrod Brown really is.

CURWOOD: Inside Climate News reporter Dan Gearino is based in Columbus and is following this contest. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Dan!

GEARINO: It's great to be back.

CURWOOD: So why is Ohio a significant Senate race in 2024?

GEARINO: Democrats barely control the Senate right now. And they have a pretty tough map. When you look at who is up for re-election, Joe Manchin is retiring, and Democrats are going to almost certainly lose that seat. That means that they pretty much need to run the table on almost all of their other close races. And that includes Ohio. Ohio is part of this short list--the others are Montana, Nevada, Arizona--of states where the Democratic incumbent or the Democratic candidate has to win, or else Republicans would take control. Unless there's some other race out there that becomes a competitive race that we don't think is competitive at the moment.

A house in Ohio displays an American flag and a flag in support of Donald Trump. Seen as a swing state, Ohio went to Barack Obama in the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections, and to Donald Trump in 2016 and 2020. (Photo: Elli, Flickr, public domain)

CURWOOD: So of course, Ohio has been thought of for many years as a swing state. In fact, Obama won in '08 and '12, right, but Trump won last time around, and won big. What sort of chance does Sherrod Brown have as a Democrat who knows how to win in Ohio?

GEARINO: I think that the fundamentals to pay attention to here, this has become a tougher state for Sherrod Brown to win. And with each successive election that he's had, you've seen a state that did go for Obama twice, a state that used to be almost the definition of a swing state that has the last two presidential elections gone pretty handily for Republicans and for Donald Trump. And a lot of the kind of, the Trumpiness of this Ohio electorate is that Democrats are losing white working-class voters. And there's more to it than that, but they're losing in rural areas by larger margins than used to before. And these are factors that if you're going to have a candidate who can kind of counteract that, who can work against that, Sherrod Brown is pretty close to, you know, if you were to design someone in a lab to be able to do that it would look a lot like Sherrod Brown. But the really tough part is he's on the ballot with Donald Trump. So presuming that Donald Trump wins Ohio by substantial enough margin, you would need some Trump-Brown voters for Sherrod Brown to win, and that's where it gets to be tough. But you look at polling and you look at some of the kind of prognostication about this race. It's viewed as a dead heat. So, there will be some of those Trump-Brown voters. The question is how many?

CURWOOD: Let's talk about Sherrod Brown's opponent, then, for the general election. Who is Bernie Moreno? He's the Republican candidate that Donald Trump has campaigned pretty heavily for so far.

GEARINO: So Bernie Moreno is a car dealer, a business person. And for the purposes of this race, I would say his identity is he is very much a Trump proxy. He's, if you like Donald Trump, you like Bernie Moreno. As far as like issue differences, and as far as the political track record of Bernie Moreno, he doesn't have a political track record, you know, he is someone who would be a first-time office holder, and this is the first time he's gotten a long look in a campaign like this. He did run in the primary for the US Senate seat two years ago, but he didn't stay in long enough to the point where people actually had an opportunity to vote for him. So, it's basically a pretty known quantity in Sherrod Brown against someone whose main selling point in the eyes of voters is that he was endorsed by Donald Trump.

CURWOOD: So, let's talk about the kind of record that incumbent Sherrod Brown has on the environment and other things. What's he look like? What's he sound like? What's he done?

GEARINO: Sherrod Brown is not to be confused with his neighbor to the east, Joe Manchin. So, both of these guys, they have to an extent kind of blue-collar credentials. But Sherrod Brown is much more of a down-the-line Democrat in terms of his voting record. And also, just in terms of his demeanor when handling major pieces of energy and environment legislation. You look at the Inflation Reduction Act, you look at the bipartisan infrastructure law, Sherrod Brown is someone who was a dependable supporter of those things. So, Sherrod Brown is someone who will talk about wanting an equitable energy transition. It has been important to him over the course of his career to have policies that make US manufacturing more competitive. And there's a lot of things in the Inflation Reduction Act that do that. But he is not someone who was going to put himself out there and say he's going to hold up a major piece of legislation because it doesn't do this or that for fossil fuels the way that, that Joe Manchin did.

Businessman Bernie Moreno won the Republican primary in the 2024 Ohio Senate seat race. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, he's on the Senate Agriculture Committee, and this is a time that they're rewriting the Farm Bill. And despite the fact that most of the money for that is around food stamps, there are, of course, important environmental aspects to the Farm Bill. How is he threading that needle? There are a lot of farmers who are fairly conservative in Ohio. What kind of support can he expect from the farming community?

GEARINO: He's able to, at the very least, kind of minimize the scale of his losses in agricultural communities, in rural communities, by being pretty friendly with farming organizations, by being on the Ag Committee and by proposing legislation that will at times take an environmentally friendly approach to agriculture practices like, say, encouraging cover crops, and framing these environmentally friendly practices in terms of incentives as opposed to penalties, which of course is about the only politically palatable way that you can do some of these things trying to get farmers to modify practices. And as our politics have changed in the last couple election cycles, you see Democrats relying so much on running up the score in urban and suburban areas, and then just losing rural areas overwhelmingly. If you were kind of drawing up the plan for how Sherrod Brown holds on to the seat, it's by losing those rural areas but not getting absolutely decimated in those rural areas. And one of the reasons he can do that is that at town halls or at events, he can talk about the issues that people care about there and seem--seem credible, seem like he's not just reading talking points off of a note card. He's clearly steeped in this stuff.

CURWOOD: Dan, Ohio is pretty big when it comes to automobiles, everything from the tire making there to actual vehicle construction, some union jobs, some not union jobs. What's going on in terms of the electric vehicle transition there? And how might that end up playing in this campaign?

A farm building in Ohio. Senator Sherrod Brown is a member of the U.S. Senate Agriculture Committee. (Photo: Tom Bower, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

GEARINO: Right now, it's an unknown how it's gonna play in the campaign. But I think that it is something I'm going to be watching out for, for a couple reasons. One is, Honda is building a gigantic battery plant in Ohio. General Motors, its joint venture that makes batteries, has a big plant in Ohio. And that's just two of a bunch of examples of how Ohio stands to benefit in a really big way from the shift to electric vehicles, in terms of adding jobs, in terms of adding investment. And in terms of the kind of partisan breakdown on this issue of the shift to electric transportation, Democrats like it a lot better than Republicans do. And it'll be interesting to see if Sherrod Brown tries to and then also interesting to see if he succeeds in saying, you know, that was legislation that Joe Biden helped to pass, that Sherrod Brown helped to pass, that is a big reason that some of these huge investments are happening. There's also this kind of anti-EV sentiment. There are those who are unionized workers who fear that EVs are bad for the long-term health of the auto worker in terms of pay and benefits, and that the shift to EVs will mean fewer workers. That's very much an open question. Whether or not that's true or not depends a lot on how well the UAW organizes battery plants. But it's something that I think Sherrod Brown could potentially argue has been a really good thing. It's also easy for opponents to just kind of stoke this anti-EV sentiment, to say EVs are new and weird and we should be scared of them. And you know, and I think that it's a sentiment that we've seen. It's a sentiment we've seen from Donald Trump, it's a sentiment we've seen from some other candidates. So, I'm curious, especially because Bernie Moreno is a car dealer. Car dealers tend to be more interested in than your average person in the new cool thing, and a bunch of automotive brands, their research and development is focusing on the electric vehicle sides of their lineups. I'm eager to see if questions about EVs come up in a debate. I'm eager to see kind of how that issue plays or if it plays very much in this campaign.

Senator Brown and Mr. Moreno diverge on the importance of electric vehicles for jobs and the environment. Above, the General Motors transmission factory Toledo Propulsion Systems (formerly known as Powertrain Toledo) recently invested $760 million in the production of drive units for electric vehicles. LG Energy Solution and Honda are currently building a plant in Jeffersonville, Ohio, that will make batteries for EVs. (Photo: MrJacon000, Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: You know, some of the record shows that Bernie Moreno is against government mandates on EVs. He's someone who speaks out for market-driven decisions, and I think it was at a rally for him that Trump went off about EVs.

GEARINO: Yes, it was at the rally just a couple weeks ago where Trump framed the effects of EVs on the auto industry as this bloodbath. And he was talking about EVs and this idea that it would be a bloodbath for the auto industry, a bloodbath for the economy, and some people heard this and thought he was talking about a literal bloodbath. I'm not really sure. But it is indicative of the way that the politics of EVs are probably going to be part of this race in some way. I don't think it's going to be a big part, but it's definitely something that we're going to see, and it'll be interesting to see how the candidates talk about it over the course of a campaign that is going to be so long, by the end of it, I swear, we're all going to just be falling over it. I joke it's gonna be like 20 eternities between now and November on this one.

CURWOOD: Dan, how much does this race matter in the context of the national elections in the presidential race, the balance of the Senate in play here, and what might happen in terms of climate and environmental policies?

Dan Gearino is a reporter for our partner Inside Climate News. (Photo: Brooke LaValley)

GEARINO: This race is incredibly important for global climate environment policy. Right now, Democrats have an incredibly thin majority in the Senate, and they're almost certainly going to lose one seat. They can't lose any of these really close races. If they lose this seat in Ohio, Republicans will most likely have control of the Senate. So if Republicans have control of the Senate, that could mean a couple different things, both of which are likely not good for climate and environment legislation. One is, if there's a Biden presidency and Republicans have control of the Senate, it will be very difficult to pass anything that would kind of expand upon what the Biden administration did with the Inflation Reduction Act and other actions. If you have a Trump presidency and Republicans, again, control the Senate and they also retained control of the House, this Republican trifecta would be able to unravel big parts of what the Biden administration just did. And the same could be said for the seat in Montana, the seat in Arizona, the seat in Nevada, and just this whole larger question of do Democrats retain control of the Senate. Any one of these seats is really important for having the ability to pass additional climate and clean energy legislation or also having the ability to stop a President Trump from unraveling some of that legislation that's already been passed.

CURWOOD: Dan Gearino is a reporter based in Columbus, Ohio for our media partner Inside Climate News. Thanks, Dan, for taking the time.

GEARINO: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- NPR | "One of the Tightest Senate Races in the Country Will Play Out in Ohio"

- New York Times | "Sherrod Brown Embarks on the Race of His Life"

- AP News| "Cleveland Businessman Bernie Moreno Lands Trump Endorsement in Ohio’s US Senate GOP Primary"

- Dan Gearino’s reporting on Inside Climate News

- Read more from Dan Gearino

[MUSIC: Zander Jazz Trio. “Let There Be Love” on Misty, Zander Jazz Trio]

DOERING: Just after the break, the Yurok tribe is getting back ancestral lands on the California coast. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Zander Jazz Trio. “Let There Be Love” on Misty, Zander Jazz Trio]

Land Back for the Yurok Tribe

(From left) Save the Redwoods League President and CEO Sam Hodder, Redwood National and State Parks Superintendent Steven Mietz, Yurok Chairman Joseph L. James, and California State Parks North Coast Redwoods Superintendent Victor Bjelajac sign the landmark agreement at ‘O Rew. (Photo: Matt Mais, Yurok Tribe)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Over the last few centuries Native Americans have endured genocide, land theft, and attempts to erase their very cultures. But they are still here, and although the past can’t be changed, there is some healing now underway. On the northern California coast the Yurok tribe is getting some of its stolen land back thanks to an historic partnership.

The National Park Service, California State Parks, and Save the Redwoods League have agreed to transfer 125 acres of ancestral lands back into the hands of the tribe by 2026. For thousands of years the Yurok have lived near the mouth of the Klamath River, where the plentiful salmon nourished them and have been invoked in dance and music.

[“NEYPUY REK’WOY” SONG BY James Gensaw Sr.]

DOERING: This song called Neypuy Rek’Woy translates to “I went down to the mouth of the Klamath and caught a lot of salmon.”

[“NEYPUY REK’WOY” SONG]

DOERING: The place that the Yurok tribe is getting back is called O’ Rew in the Yurok language and includes habitat for young coho and chinook salmon. Joining me now is Joseph L. James, Chairman of the Yurok tribe. Chairman James, welcome to Living on Earth!

The 125-acre ‘O Rew property, part of traditional Yurok lands, used to be a mill site. (Photo: Matt Mais, Yurok Tribe)

JAMES: Thank you, glad to be here to talk about a historical moment for the Yurok tribe and its people.

DOERING: So first, Chairman James, can you tell me a bit about your people, the Yurok tribe, and your traditional lands? What are some of the core values of your culture?

JAMES: We're the largest populated tribe in the state of California. Our Yurok reservation is located in two counties, Humboldt and Del Norte county, up here in northern California along the Klamath River, just south of the Oregon border. We're river people. The Klamath River is our life way. We're a fishing tribe. So we're very grateful and appreciative of what the land and the river provides for us. Salmon and fishing, it's not just a food, it's our culture. It's our way of life as people.

Yurok children at play. The Yurok Tribe is the largest Tribe in the state of California, with over 6400 enrolled members. (Photo: Matt Mais, Yurok Tribe)

DOERING: And tell me more, please, about this place that we're talking about here, the 'O Rew land. You know, Save the Redwoods League is involved in this land back, so there must be redwoods there. I remember going to that Northern California coast a long time ago and it's very lush, rainy a lot of the time, but that makes it so prolific and there's so much nature and wildlife there. Can you describe that a little bit for us?

Tribal members in Yurok adornments. The Yurok Tribe plans to build a traditional village at the ‘O Rew site, where their community can gather for ceremonies and other cultural activities. (Photo: Matt Mais, Yurok Tribe)

JAMES: This property of 125 acres used to be a mill site, you know, where they decked back in the day-old growth logs and the large second old growth logs, specifically redwood. It's one of the southern areas from our reservation. It's a gateway into the redwoods. We have used redwoods for our ways of housing and lodging. We use our redwoods for our dugout canoes for traveling on the river. We also have streams running through the property along the highway. We have beaver there, we have small juvenile salmon, we have coho there. So, we're really excited to have our piece of property come back to the Yurok tribe, it's an old village site for us. It's exciting times.

DOERING: And by the way, what does 'O Rew mean in your language?

JAMES: It's the name of the village and location. A number of Yurok people have come from villages along the Klamath River and along the north coast. And so again, it's just our place of origin, where we come from.

DOERING: How do the Yurok people want to transform this piece of land that will be returned to you in 2026? What are your plans?

The Yurok people have been involved in restoring this area for over a decade. They plan to continue this work when the land is transferred to them in 2026. (Photo: Matt Mais, Yurok tribe)

JAMES: What we'll have is a visitor center here on the property, we'll also have a cultural center there, where we'll showcase our materials that we have used, whether it's making for boats, whether it's materials we gather for making baskets. So, we'll have our cultural items there that are appropriate to share. And then we'll also have a traditional village there that will be used by our tribal citizens. You know, we continue to dance, we continue to have our ceremonies, we continue to pray and continue to gather. We're looking forward to showcasing this with our young men, our young women and our adults, and a place to come, to gather, to continue that traditional practice. Also, this area, we have trail systems and networks of trails that we use for our ways of travel. And so, we're gonna include a network of trail systems there, using our Yurok language, using traditional knowledge of way showing and interpretive signage, plants, animals, what has the Yurok tribe since the beginning of time utilized these resources for, from a traditional perspective, not from a Western science perspective. That's what I'm so also proud of, the land not just coming back to us, but as first peoples, we get to share that knowledge and experience of what the work we have been doing since the beginning of time as people.

The Yurok Tribe has released 11 California condors in their ancestral areas. (Photo: Matt Mais, Yurok Tribe)

DOERING: So even though there has been logging of redwoods and other trees in this area, to what extent has the forest been able to grow back over time and with your help as well?

JAMES: Yeah, the Yurok tribe has been involved in this rehabbing the area to its original state for last 10 years. I'll start along the stream, the work that we've been doing, improving that stream habitat for our young juvenile fish to return, putting root wads in the streams, and also planting new trees along the stream bed to provide shade and canopy. It's exciting that we're doing the great work we're doing, improving habitat and salmon for future generations to come. You've got elk on the property. We just reintroduced the California condor. It's been 100 years since the California condors come back home to Yurok country. Now we have eleven flying California condors, probably about maybe 10 miles from this location. It's gonna take time, it's going to take time to bring the piece of property back to its original state, but we're fully invested in it. And we're able to have the help with our partners of Save the Redwoods, the California State Parks, and Redwood National Park. Our values and missions align. And we're continuing to continue that great work moving forward.

Elk roam the ‘O Rew area. (Photo: Matt Mais, Yurok tribe)

DOERING: Yeah, and this is a historic partnership with Redwood National Park, California State Parks and Save the Redwoods League working with the Yurok tribe on this land management. How have you collaborated with these folks in the past and how do you hope to grow that bond in the future?

JAMES: The Yurok tribe has a long-standing relationship with all three of them. The Yurok tribe has been working with the California state park system, you know they're located in the Yurok tribe's ancestral territory, so we do a lot of work with them, through trails improvements, through our cultural projects. You know, Redwood National Park is also located in the Yurok tribe's ancestral territory. So, the same model there, we've been working with the Redwood National Park regarding trails, maintenance. Save the Redwoods, you know, within the last 12, 13 years. They purchased this property in 2013. They are aware it was in the Yurok ancestral territory; they reached out to us. And, you know, we just had that conversation, and we've just grown over the years. And how you get to that trust is just sitting at the table in the room and growing that bond. Doesn't happen overnight, doesn't happen over, over one year. We're not looking to build trust for short term, we're looking to build for long term. And that's what you have here. And when I look at that, I've got a private organization, I've got a federal organization, and I've got a California state organization, giving land back to the Yurok tribe, right? You let that sink in. We all aligned and through discussion, partnership and trust, and collaboration, we are transferring 125 acres back to the ownership of the Yurok tribe. So, we're really proud of that.

A Yurok child holds a wooden carving of a salmon. Salmon and fishing are an integral part of the Yurok culture. (Photo: Matt Mais)

DOERING: Chairman James, what is this return of the 'O Rew land mean for the Yurok people?

JAMES: It means healing. Healing for myself, healing for our people, and now we got to heal the land and the property. It means excitement, it means very proud, privileged, and honored to have this piece of property come back in the hands of Yurok. Knowing how far we have come through the state of California, even across the nation, as indigenous people. How far our ancestors have paved the way to get to this point, knowing our people had to get sent to boarding schools, knowing their language at one point tried to wipe our language away. It wasn't successful. We're still here today practicing our culture, our traditions. And when I see this piece of property, in a village coming back with the Yurok ancestral territory, it makes my heart feel good. But also at the same time, we've got a lot of work yet to do. This is just one piece of property that we have.

The Yurok people will steward the land alongside their partners, Save the Redwoods League, California State Parks, and the National Park Service. (Photo: Matt Mais, Yurok Tribe)

DOERING: We've heard in recent years about this movement for land back in North America. How do you hope that this project and this land transfer might kind of help ignite that and transfer into other traditional lands?

JAMES: We look at this partnership, the way we've come together, it's not just for us. It's for all of Indian country. It's for all of us to to share, this model is for us to share. And again, it's a first of its kind here in our neck of the woods, up here in northern California. So, it's truly a historical moment for our land to come home, gives not just us hope, but gives others hope.

DOERING: Joseph L. James is Chairman of the Yurok tribe. Thank you so much, Chairman James.

JAMES: Thank you for having me on the show.

Related links:

- Yurok Tribe | “Save the Redwoods League, the Yurok Tribe, and Park Partners Sign Historic Agreement to Return Tribal Land”

- Learn more about the Yurok Tribe

- Living on Earth | “Replanting the Klamath River”

[MUSIC: “NEYPUY REK’WOY” SONG BY James Gensaw Sr.]

The Little Gods of the Forest

Major Jackson’s poem the Body’s Uncontested Need to Devour, An Explanation is inspired by the moss he sees during his long walks across the Vermont forest. (Photo: Joshua Mayer, Flickr CC BY SA 2.0)

DOERING: April is National Poetry Month, so we turn now to a poem inspired by lush mossy forests like the redwoods. Here’s Major Jackson with his poem “The Body’s Uncontested Need to Devour, An Explanation.”

I am bathing again, burying my face

into the great nations of moss.

I am leaning in, smelling the emerald mountains

and the little inhabitants crossing

over rock-like boulders and tree trunks empired

bit by bit. My nose must come to them

like a probing spaceship causing a mighty eclipse.

They speak in whispers but do not shriek

when gazing into the dim landing bays

of my cavernous thoughts. I am grazing

like a Dionysian. I come not with religion.

I come yearning for first spring and a thirst for spores

pooling like mercenaries in the dark.

The little gods of the forest live here.

I want to ingest their verdant settlements

until they carpet my cavities and convert my raptorial

self into its own ecosystem, off into the green.

Major Jackson is an American poet and professor at Vanderbilt University. (Photo: Patrice O’Brien)

DOERING: Towards the end it seems like you are contemplating dissolving into this green world, into this ecosystem. Can you talk about that?

JACKSON: Yeah. Well, we've all heard the term forest bathing now and Shinrin-yoku and the idea of healing through nature. And some part of me experiences that every time I go out as a transformation of sorts. And so, in that particular instance, I am alluding to that feeling that I get. But I also as a Dionysian, you know, someone who wants to not only experience that healing but also someone who believes that this is how we remain alive. We are part of the biodiversity that makes up our ecosystem, so that interrelatedness, that sense of life giving life is kind of what I'm exploring there. Which may mean interestingly enough, now that you pose that question there, which may mean a dissolving into the world around us, which we know we're eventually going to do. So, there's this wonderful kind of tension there.

DOERING: Major Jackson is a poet and Professor at Vanderbilt University and the host of the Slowdown Podcast. Thank you so much for joining us Major.

JACKSON: Thank you Jenni, it’s been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Learn more about Major Jackson

- Major Jackson’s profile from the Poetry Foundation

- The New York Times | “The Body's Uncontested Need to Devour, An Explanation”

- Orion Magazine (No paywall) | “The Body’s Uncontested Need to Devour, an Explanation”

- Pre-order Major Jackson’s forthcoming book of poems “Razzle Dazzle”

- Follow Major Jackson on Instagram

- Listen to “The Slowdown” podcast, hosted by Major Jackson

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Upholding”]

From the History Books

Conservationist Marjory Stoneman Douglas, author of The Everglades: River of Grass, lived to be 108 years old and was 104 when this photo was taken. (Photo: Abigail B. Wright, Miranda Productions, Inc., Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia is Peter Dykstra, Living on Earth contributor who takes a look at history for us. Hey, Peter, what do you see now in the history books today?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. We're going to go back to April 7, 1890, and the birth of a true environmental hero and journalism hero Marjory Stoneman Douglas born in Minneapolis, but she made her fame and her impact in Miami, Florida. A reporter for the Miami Herald, later a columnist, she wrote frequently about the Everglades and how they were becoming endangered. But in 1947, she gave up her first career and started her second as a full-time environmental advocate, writing the book River of Grass. Bear in mind 1947 Marjory was already 57 years old starting a new career.

CURWOOD: Fifty-seven years old, and how long did she live?

DYKSTRA: She lived until age 108. She died in 1998. Before then she became the most effective advocate for protecting the Everglades, seeing it become first partly a state park then later a national park. She was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Clinton in 1993. And up until age 108, she was active almost till the very end of her life.

CURWOOD: What else do you have for us, Peter?

DYKSTRA: We can go back to April 6, 1954, what is generally noted as the first sale of the TV dinner. Swanson company offered four entrees, none of which made great service to the American diet, meatloaf, fried chicken, turkey, or Salsbury steak — those little hockey pucks of beef that were so common in college cafeterias. They were baked in a frozen tin foil tray that sold for 98 cents.

CURWOOD: And Swanson called this the TV dinner because?

DYKSTRA: Because people were tempted to eat those dinners while sitting in front of the TV, watching I Love Lucy or the Honeymooners or Gunsmoke. They sold 10 million TV dinners in the first year.

The original TV dinners came in tin trays and today they are typically packaged in plastic. (Photo: Sir Beluga, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

CURWOOD: And I wonder how many households stopped having dinner around the dinner table and instead just watched television.

DYKSTRA: It put a real dent in those family dinners at the dinner table. It has many descendants today, with microwave dinners becoming a staple for families eating on the run, working two jobs, and all sorts of other things.

CURWOOD: And Peter, I guess you can't exactly put a 1954 TV dinner in 2024 microwave these days.

DYKSTRA: Not with that tin foil tray unless you wanted to watch your microwave spark and burn.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is a regular contributor Living on Earth. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth webpage. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Florida Everglades, the habitat Marjory Stoneman Douglas fought so hard to protect

- Read a history of the TV dinner

[MUSIC: Desi Arnaz Orchestra with pianist Marco Rizo, “I Love Lucy” Theme Song, by Eliot Daniel]

DOERING: In last week’s broadcast, in our story about PFAS in sewage sludge we misreported the home state of farmer Wilbur Tennant. He was a West Virginia farmer, and we regret the error. Coming up, a dystopian novel with a message of hope for vanishing species. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Toby Walker, “Generosity Rag” on Hand Picked, by Walker, BAND IN THE HAND RECORDS]

Migrations: A Powerful Novel About A World Losing Life

The Arctic tern has the longest migration route out of any bird. Every year, it flies from the Arctic to the Antarctic and back. (Photo: Ed Dunens, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

With summer just around the corner you might be starting to dream of books to add to your reading list, and if you like fiction we’ve got a true standout to suggest. The novel Migrations by Charlotte McConaghy uses beautiful prose to explore the core theme of climate disruption. Migrations is set in a future in which many of the animals we know and love, like polar bears and the great apes are extinct and the oceans are running out of fish. Yet, the Arctic Tern, a bird known for having the world’s longest migration, remains. In years yet to come one woman follows what might be the very last migration of Arctic Terns from pole to pole. But this work of fiction is about a voyage of discovery far beyond the birds. Charlotte McConaghy joined me back in 2020 from her home in Australia and I asked her to start by reflecting on what inspired her to write Migrations.

MCCONAGHY: Well, it's tricky for me to pinpoint it because it was one of those things that came in a lot of different pieces. It was quite fragmented. But I wanted to engage with my kind of concern around the climate crisis. But I didn't know how, because it felt just far too big. So, I sort of parked that notion. And I went traveling, and I wanted to explore the UK, which is where my ancestors are from. And I started noticing all the beautiful birds, the migrating birds over there, particularly the graylag geese, which I learned about while I was in Iceland. And I just became really fascinated with where they must be flying and these incredible journeys that were going on. And I started thinking about the idea that wouldn't it be amazing if we could follow them and experience those, those migrations with them? So, I think that's where that initial spark of an idea of this woman who's following the last migration of the Arctic tern.

CURWOOD: So, tell me, I mean, of all the animals on this planet, why the Arctic tern?

MCCONAGHY: Well, I didn't know initially, which bird she would be following. So, I did, I was doing a lot of research into a lot of different birds. And the moment I came across the Arctic tern, I knew it was the one - I fell in love with it. It has the longest migration of any animal in the world, from the Arctic to the Antarctic, and then back again within a year. And because it lives for about 30 years, over the course of its lifespan, it will fly the equivalent distance of to the moon and back three times, which I just thought was absolutely beautiful and kind of amazing that such tiny creatures could go so far for survival, and we're making this journey more difficult for them every year. So, they sort of became a metaphor for courage, the courage that Franny would need to take on her journey, and I think she takes a lot apart from them. If they can do it, then she can, too.

CURWOOD: So recently, we've been learning quite a lot about the emotional toll that climate anxiety and climate grief have for so many of us. How do you think this affects Franny, the protagonist of your novel?

MCCONAGHY: Quite severely. I think one of the reasons that I wanted her to be such a migratory creature herself, and such a wild creature, and so similar to the animals that she loves, is because I wanted her to have a really deep connection to the natural world, which would allow her to be a great mouthpiece for her to experience the loss of this wildlife and the natural world that's disappearing piece by piece, just as we're losing it. I think she suffers that grief, perhaps more intensely than the rest of us do, which is why she's so driven to do something about it.

Migrations tells the story of one woman who wants more than anything to follow what might be the very last migration of the Arctic tern. (Image: Flatiron Books)

CURWOOD: Yeah, she's willing to risk her life to follow this passion.

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, that's right.

CURWOOD: One might say in some respects, climate change is perhaps changing everything. I mean, it just has so many impacts on the way that we're living now. But your character Franny is looking at the human aspects on the climate largely through their effects on animals. So, what is it do you think about animals that so resonates with Franny?

MCCONAGHY: I think, I think because she grew up without a family, she made a family of the wild creatures around her and the natural spaces. So, they became a kind of home for her when she didn't have a normal home. And they became her loved ones when she didn't have anyone else to cling to. And so, I think a big part of her is bound to these creatures. And I think also one of the things that originally was an inspiration for me was growing up, I really loved Celtic mythology and the myth of the Selkie, which is the story of seals that can shed their seal skin and become humans. And they can, the tragedy of the selkie is that they can fall in love and get married and have children, but they'll always be bound to the ocean. And this is something that kind of plays into Franny and her character. She says, at one point in the book, it's not fair to be a creature who is able to love but unable to stay. And so, I think that that is also part of her creaturely-ness, and this idea that she's not, she doesn't subscribe to a lot of societal values. She has no ambition. She doesn't want wealth. She is really just living in the moment, in a way that I think we all would love to be able to.

CURWOOD: Mm hmm. And she loves water, or she certainly spends a lot of time in and around and above water.

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, she absolutely does. And I think that's another element of that selkie myth coming in. I've always loved the ocean, there's something very mysterious and frightening and wonderful about it. I guess it's the most important part of our planet, really, because we're the only planet that has ocean which makes it a habitable planet for us. So, there's something kind of immense and important about the ocean. I hate the idea of it being pillaged for our benefit.

CURWOOD: And of course, Franny's quite concerned about, shall we say, overfishing?

MCCONAGHY: She is. Absolutely, yeah, it's a real problem for us. And in the world of the book, it's even more of a problem. And so, there's that terrible conflict for her that she has to talk her way onto a fishing boat. And it's the only way that she's going to be able to fulfill her journey. But it's sort of really gets under her skin. She hates it because she's so anti fishing. But I think that's one of the things that this book is about it. It's about overcoming our judgement of the other side of this as this big schism in the world, I think, between conservation and fishing and farming. And, and one of the things that this book, I think, is trying to say is that we need to be able to communicate and not judge each other in order to understand each other and actually try to find ways to support each other to move beyond the employment the way it is now and make it sustainable for the future.

CURWOOD: In other words, we're all in this thing together.

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, that's exactly right. Yep.

CURWOOD: So I guess it was Camus, who said, if you want to be a philosopher, write novels, maybe you took that to heart because at one point, you start, you have this discussion about whether people should work to save, quote, important animals, the ones that benefit societies versus working to save everything that seems to be slipping away from our ecosystem. And Franny is not happy that people would even think about making this choice. I think she says, and let me quote here, it's page 209: "What of the animals that exist purely to exist because millions of years of evolution have carved them into miraculous being?" So, talk to me about this discussion and why you decided to include it in this book.

A baby Arctic tern. (Photo: Gregory Smith, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, I think this really strikes to the heart of what the book is about, actually. It really upset me to think about the fact that in a dire future, we would only be focused on saving the animals that provide us with some measure of survival, the ones who offer us something. So, at this conservation base in the book, they're putting most of their resources into saving the pollinators because they're an integral to our food sources. But yeah, as you read, Franny voices something that I found really tragic myself and I struggle. I know that there's practicalities that need to be taken into account, but it seems immensely unfair, the tragedy of leaving all the rest of the animals to go extinct. You know, it's not their fault that they can't survive. It's our fault. And I think I realized that by writing this book, I was trying to remove humans from the center of all things, trying to point out that we are not the only creatures on this planet that have a right to be here and that deserve survival. And we shouldn't be behaving as though we are. I think, in a way, it's a love letter to animals, not because of what they offer us. But just because they're beautiful in their own right. And we would have a much poorer world without them. Biodiversity is key, but on a purely emotional level, we will have such immense loss if we let go of the animals.

CURWOOD: It makes me wonder if they could get together and let us go, would they make that choice?

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, I think they would if they could, although there are a lot more compassionate than we are, I think.

CURWOOD: In that same section of your story, you also have a scientist saying that birds should be contained and stopped from migrating as a way to save them. And yet, the husband of your main character here claims that migration is well, it's just part of being a bird. Talk to us about these dueling ideas and how this discussion made it into the book.

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, well, this was me trying to put myself in the headspace of the scientists and conservationists who are having to figure out how to save these animals, and really trying to imagine what we need to be doing. What do you do if you have an animal that is instinct bound to go on this epic migration in order to find food and breeding grounds, but the journey itself isn't survivable for them? Do you contain them to feed them and keep them alive? Do you force them to adapt? Or, is our involvement in their existence part of the problem that got us into this mess in the first place? Are we having too much of an impact on them? And should we just leave them alone? I don't really know what the answer is. And I think it's clear in the book because there's this ongoing discussion. I do think it's crucial for us to save critically endangered animals from the planet that we made too hard for them. You know, that's the least we can do. But there's something that sits very wrong for me in trying to change their fundamental natures, and the instincts that have led them through those millions of years of evolution. I find it heartbreaking thinking of caging birds.

CURWOOD: And don't imagine you think much of zoos then.

MCCONAGHY: I struggle with zoos, I don't like them. I like it when they use their resources for conservation efforts. But I don't visit them because I find it too sad.

CURWOOD: So, the title of your book is Migrations. So, what does the theme of migration mean for you in writing this book?

MCCONAGHY: Well, it was initially just about the birds. As I said, I was traveling around the UK and looking for a sense of roots and history and belonging. And I became fascinated with the gorgeous birds that I could see. I think I was fascinated with the idea of movement for survival, and what that might mean for humans, because it often means the same for humans. But I wanted to explore a character who had a kind of driving force inside her, and instinct like the birds for movement as survival, and yet, it was more of an emotional survival than a physical one. And I knew that pretty quickly, the kind of woman who would follow these birds would have to be a fairly special person, she started to form into this wild creature in my mind, who never stops moving, always roaming. And this impacts her relationships quite badly. But it's a compulsion of sorts like it is for the animals, she's searching for where she belongs. And I guess that kind of started bringing up the idea of people who don't know where they belong. And that can certainly be true of settler societies and migrant families, they can often feel a bit rootless, I think. Franny is kind of straddling these two worlds, one that belongs to the people who stayed and abound to their homes, and then one that belongs to the people who left, and perhaps maybe lost that sense of home. I think that's the complexity of migration for people.

Charlotte McConaghy is the author of Migrations. She lives in Sydney, Australia. (Photo: Emma Daniels)

CURWOOD: Now, your story has a lot of destruction, a lot of loneliness. And the impact of human activities is apparent on many of the pages of this book. Yet, somehow, it's fair to come away from it with a sense of hope. So, talk to me about hope and, and how is it that you're able to cast a spell of hope in such a dark tale as this one.

MCCONAGHY: It wasn't easy to be honest. I'm an optimist at heart. I couldn't live if I didn't think there was hope. But all joy in life would be gone for me. But writing this was one of the most difficult things I've ever done, it took me to some very dark places, and I often felt lost in them. So, I would stop, and I'd go outside. And I think even without realizing it, I'd be taking nourishment from the little pieces of the natural world around me that I could find, the birds that I spotted walking in trees, even if there are only a few. I'm city bound, so it was not always easy to find these little pockets of wildness. But you can do it if you're looking for them. And I read a lot of Mary Oliver poetry, which is all about our connection to nature and how it can feed our souls. And that would kind of inspire me to look around and see the truth of the fact that there's so much we haven't yet lost. That's what kept me going. I think we're saturated by bad news these days. It comes at us from every angle, and it's easy to become apathetic or to give up. But now is not the time to give up. It's the opposite. It's the time to fight. And it was really important to me that this book be about hope more than anything, because hope is energizing, it leads to action. And that's what we really need. I think in some ways, the book is a battle cry, and it’s reminding myself of that is how I kept going because I was able to see that there's hope everywhere. It's in the kindness and the generosity that we show each other every day. That's the real stuff. And I think that's what we need to be feeding.

CURWOOD: Charlotte McConaghy is the author of the novel Migrations. Charlotte thanks so much for taking time with us today.

MCCONAGHY: Thank you so much for having me. It's been lovely to chat.

Related links:

- Migrations by Charlotte McConaghy

- More on Charlotte McConaghy

- Purchase Migrations and support both Living on Earth and local bookshops

[MUSIC: Xavier Rudd “Follow The Sun” on Spirit Bird, Salt.X.Records Ltd]

CURWOOD: Next week on the show, EPA bans asbestos thanks to new authority from Congress.

DOA: It's extremely important that EPA is finally banning chrysotile asbestos, which, is still used in industry and also in some consumer products including after-market brakes. So, there's a potential for exposure from all these uses. So, it's really important that the door is finally going to be closed on this very deadly chemical.

CURWOOD: That’s next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Xavier Rudd “Follow The Sun” on Spirit Bird, Salt.X.Records Ltd]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mattie Hibbs, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth