Poetry in the Time of Climate Troubles

Air Date: Week of April 12, 2024

Poet Catherine Pierce confronts the climate emergency head-on in her work, and even finds beauty within it. (Photo: Catherine Pierce)

In her poems, Catherine Pierce grapples with unfolding climate disaster and other 21st century perils, and the ways they reframe parenting. She joins Host Steve Curwood to share poems from her books Danger Days and The Tornado Is the World, and to reflect on finding beauty and calls to action during the Anthropocene.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The climate crisis is picking up pace, with important heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere at record levels in 2023, which was also the warmest year on record in modern times. And as we heard earlier in the show, forecasters are predicting a busier than usual hurricane season this year thanks in part to warmer than ever sea temperatures. Science can help us understand our disrupted world, but poetry can also enlighten us. So as Poetry Month continues, we turn to Catherine Pierce, Poet Laureate of Mississippi. Her poetry collections include Danger Days and The Tornado Is the World. Catherine Pierce, welcome to Living on Earth!

PIERCE: Thank you so much for having me on.

CURWOOD: Our pleasure. So Catherine, environmental disaster seems to be, well, can I call it a muse of sorts for you? Tell me, tell me why is that?

PIERCE: [LAUGHS] That's a great question, a muse! Yeah, I guess, I mean, I guess we could call it that. It's a terrifying muse, but I guess we could call it that. I've become increasingly impacted, just in my day-to-day life, by extreme weather, by these things that are changing, in the way that I think a lot of us have. I live in Mississippi and we've had, you know, more and more tornadoes, tornadic weather, strong storm systems coming up through the Gulf. And people's lives have just been completely disrupted and sometimes destroyed by these things. And so that's part of it, is having had some very real experiences, very close calls with tornadoes, and knowing a lot of people who have had homes destroyed, or who have lost loved ones because of these things. And I also became a mother while I was living in Mississippi, I have two kids, and we try to get outside a lot, we try to experience the outside world as much as we can. And it's a thing that brings us a lot of joy. But there's something about trying to impart that joy to my children; it's always kind of tinged with this sadness, or this feeling of guilt as I think about how this world as we know it is shifting every single day. And what's going to be left by the time they're my age?

Photomontage of the evolution of a tornado: Composite of eight images shot in two sequences as a tornado formed north of Minneola, Kansas on May 24, 2016. (Image: JasonWeingart, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: Now, if you grew up near the Chesapeake, then you must have been well aware of nature as a child, as a young person coming up. What's changed about your perception of the environment now, as an adult in these times of climate disruption?

PIERCE: I mean, one thing that I've noticed is the fact that small things are different. Things like the fact that when I was growing up, we had snow pretty regularly, you know, up in Wilmington, Delaware, where I grew up. And now there's less of that. I mean, we're getting extreme snow, we're getting crisis snow. But we're not getting as much of that sort of reliable, pleasant, you know, several inches, close-the-school-for-a-day kind of snow. And so you know, you see these little changes. Or I see things like, I teach at Mississippi State, and we have this beautiful campus with all these beautiful blooming trees. And a couple of years ago, I remember walking outside and seeing that one of our trees near the English building was blooming, but it was the fall, it was a tree that should be blooming in the spring. And the tree was confused, something about the weather had, had confused it. So and you know, you see these things occasionally. And then thinking about just extreme weather popping up throughout the country, the tornadoes that are getting increasingly bad in the Deep South, and also in the Midwest; the extreme weather that we saw in Texas not so long ago. All these things, all of this extreme weather that's coming through, all as a result of disruption and of climate crisis. And these are things that, you know, again, I'm observing from the perspective of just a person, you know, living my life. And I'm not a meteorologist, I'm not a scientist, but I'm paying attention. And I'm aware of the way the sun feels on my face. And I'm aware of the way the wind feels when I step outside. And they're subtle shifts, but they're very real, and if you look at the data, all the stats are there. But I think we can see it in very day-to-day ways as well.

CURWOOD: You have a poem that I'd like to ask you to read that really seems to capture, well, kind of the element of, of exhaustion of dealing with constant climate disruption now. It's called, If/When.

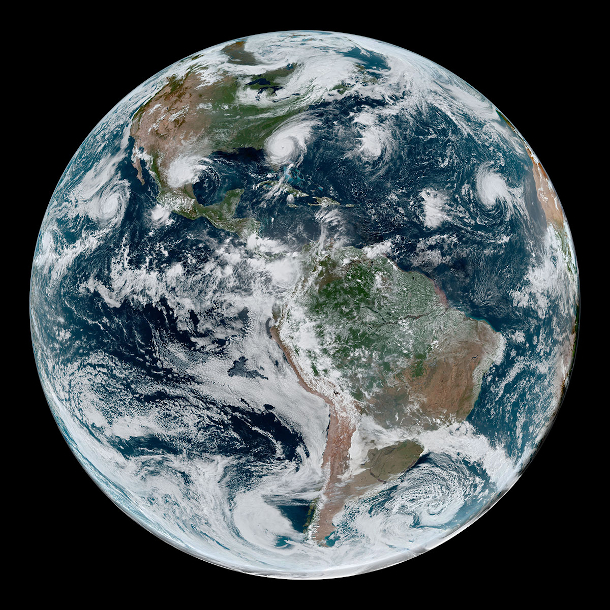

On Sept. 4, 2019, a chain of tropical cyclones lined up across the Western Hemisphere. (Image: NASA Earth Observatory/Joshua Stevens; NOAA National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service)

PIERCE: Yeah, this poem was first published in the Southern Review.

If/When.

The poem I planned to write

was about last week’s hurricane,

about how I live in Mississippi,

not that far from the storm’s rages,

and how even still we felt

nothing here, nothing at all.

That was going to be the ending,

because I wanted to make a point

about how easy it is to ignore

disaster when it’s not churning

directly over your town, and I was hoping

a reader might then extrapolate

a larger point about disturbance

and proximity, like how politicians

are always saying they used to oppose X

until some terrible Y happened

to their daughters, and it seems

to me we’re requiring an awful lot

from daughters these days. Sons, too.

This week a message from my kids’

school district included the phrase if/when

a lockdown is ever necessary. The reason

I’m writing this poem instead

of the one I’d planned is that I keep

thinking about that email and also

now the hurricane was a week ago

and there’s a new disturbance

forming near the Bahamas. And

last night Sioux Falls was tornado-

shredded and in Sterling, Colorado,

egg-size hail pummeled windshields,

and I guess what I’m saying is, why bother

with one poem about one hurricane,

one email? There will be more,

and there will be more,

and there will be more until

there is nothing left. The thing

about the poem I was going to write

is that it would have been a lie.

That nonsense about how we don’t

feel it here. We feel it everywhere,

don’t we? Dear daughter, dear son,

dear someone’s something, we’re well

past the if and into the when.

Talk about proximity—

some days I wear the world

like a skin. I am tired of waiting

for extrapolation. Let us all

be disturbances now.

CURWOOD: Yeah. So what are the climate impacts that have made perhaps the deepest impressions on you?

PIERCE: Certainly, for me, it's been the tornadoes that I've seen living in Mississippi. And we see tornadoes every year, we have tornado warnings regularly in the spring and fall especially. And, you know, the sirens go off, and everyone's in their bathtubs, because we don't have basements there because the, the water level is too high. So everyone just hunkers down in their bathtubs and hopes for the best. But that for me has had a huge impact. In 2011, that was when the tornado super outbreak occurred, if you remember that, that really decimated a lot of the Deep South. More than 300 people were killed that day, and thousands more were injured. And on that day, I happened to be traveling with my husband and our infant son—I had just had my first son, he was four months old—and we were driving. We knew the weather was supposed to be bad, but we didn't really have a sense of things exactly. And this was before we had smartphones, so we couldn't really check anything, we just had the radio on as we were driving. And we got to Cullman, Alabama, and saw that the sky looked really bad and really strange. And so we pulled over and went into a Days Inn. And soon as we got inside, some people came running in saying, it's out there, the tornado was coming. And so we all, me and my husband and our son, and the few people in the lobby, we all ran into the bathrooms because they were the most interior rooms off the lobby. And we all just kind of hunkered down there. And I just remember people screaming, and the power went out. And I mean, it was definitely the scariest single moment of my life, and we were all pretty sure we were going to die. And we didn't, obviously; and the tornado did not hit the Days Inn where we were, although it did hit Cullman, and several people were killed, and many more were injured. But we were very lucky. And that experience crystallized a lot of things for me about weather and climate, but also about being a parent, and being a parent who writes poems. And that experience became the catalyst for the book that I went on to write, which was called The Tornado Is the World, and became sort of a lens through which I could explore parenthood, which was new for me, and which I didn't quite know how to write about yet. And so I did, I developed a series of personae in that book and used those and sort of created a narrative of people dealing with the aftermath of an EF4 tornado, which was what that tornado had been.

Pierce composed the poems in The Tornado Is the World in the aftermath of the 2011 Super Outbreak that left a swath of destruction through Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee and other states. (Image: Courtesy of Catherine Pierce)

CURWOOD: So, why don't you read one of your tornado poems for us?

PIERCE: Sure. And this was the first poem that I wrote after that tornado experience. And so this is the one that is pretty autobiographical, at least in terms of what I was feeling in that moment. And in the book, the tornado takes on its own persona, because to me, it always feels like a tornado has agency. I always feel like it's making a decision about what it's doing, somehow. And so this poem addresses that. It's called The Mother Warns the Tornado.

I know I’ve already had more than I deserve.

These lungs that rise and fall without effort,

the husband who sets free house lizards,

this red-doored ranch, my mother on the phone,

the fact that I can eat anything—gouda, popcorn,

massaman curry—without worry. Sometimes

I feel like I’ve been overlooked. Checks

and balances, and I wait for the tally to be evened.

But I am a greedy son of a b****, and there

I know we are kin. Tornado, this is my child.

Tornado, I won’t say I built him, but I am

his shelter. For months I buoyed him

in the ocean, on the highway; on crowded streets

I learned to walk with my elbows out.

And now he is here, and he is new, and he

is a small moon, an open face, a heart.

Tornado, I want more. Nothing is enough.

Nothing ever is. I will heed the warning

protocol, I will cover him with my body, I will

wait with mattress and flashlight,

but know this: If you come down here—

if you splinter your way through our pines,

if you suck the roof off this red-doored ranch,

if you reach out a smoky arm for my child—

I will turn hacksaw. I will turn grenade.

I will invent for you a throat and choke you.

I will find your stupid wicked whirling

head and cut it off. Do not test me.

If you come down here, I will teach you about

greed and hunger. I will slice you into palm-

sized gusts. Then I will feed you to yourself.

Debris and damage from the EF4 tornado that hit Cullman, Alabama on April 27, 2011 while Pierce and her family sheltered inside a Days Inn. (Photo: WildBamaBoy, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: How fair is it to say that the climate has given you PTSD?

PIERCE: Oh, very fair. [LAUGHS] I think that following the tornado experience, that was something that I hadn't realized that was what I was kind of working through in writing those poems. But it, but it was, and a lot of those poems deal very directly with that, with that feeling of not being able to see the world the way that you saw it prior to this event.

CURWOOD: And as a mother, how do your kids shape your writing about something that, well, it's in the process now of impacting their lives, and it'll be with them for a long, long time?

Danger Days, Pierce’s latest book of poetry, confronts climate disruption and other 21st century perils while bearing witness to the beauty in their midst. (Image: Courtesy of Catherine Pierce)

PIERCE: Absolutely. Well, so I, my book Danger Days came out in October of 2020. And that book deals a lot with climate crisis and a lot with parenting through climate crisis, and thinking about ways that I can try to, you know, hold these two ideas simultaneously. The idea of being afraid and angry and trying to take action on behalf of the planet; and genuinely celebrating and finding joy in all the marvels of our planet. And trying to impart that to my kids, trying to say, Yes, let's go out, and let's find these beautiful things. And look, there is a blue heron, and oh my gosh, let's find out what kind of flower this is. And so trying to kind of find that balance of not wanting to frighten my kids, but also wanting them to be informed, while still finding genuine joy in our amazing planet and all it has to offer.

CURWOOD: Catherine, there's another poem of yours that grapples with what some might even see as beauty in climate disruption. It's called Anthropocene Pastoral. Could you read that for us and set it up for us as well?

PIERCE: Absolutely. So this poem is called Anthropocene Pastoral, and I wrote it following the California superbloom of 2017, when the deserts in California were covered in just these gorgeous, gorgeous wildflowers, and people were flocking there to see them. And when I did some reading about this, I found that this was caused by, the region had had its worst dry spell in history. And then it was followed by twice the normal wintertime precipitation. And that led to this really beautiful event. And so I was thinking about that, as I was writing this poem about the ways that sometimes destruction can look like beauty, can be beauty in a way.

The 2017 southern California super bloom, seen here at Walker Canyon, inspired Pierce’s poem “Anthropocene Pastoral.” (Photo: Beau Rogers, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

This is called Anthropocene Pastoral.

In the beginning, the ending was beautiful.

Early spring everywhere, the trees furred

pink and white, lawns the sharp green

that meant new. The sky so blue it looked

manufactured. Robins. We’d heard

the cherry blossoms wouldn’t blossom

this year, but what was one epic blooming

when even the desert was an explosion

of verbena? When bobcats slinked through

primroses. When coyotes slept deep in orange

poppies. One New Year’s Day we woke

to daffodils, wisteria, onion grass wafting

through the open windows. Near the end,

we were eyeletted. We were cottoned.

We were sundressed and barefoot. At least

it’s starting gentle, we said. An absurd comfort,

we knew, a placebo. But we were built like that.

Built to say at least. Built to reach for the heat

of skin on skin even when we were already hot,

built to love the purpling desert in the twilight,

built to marvel over the pink bursting dogwoods,

to hold tight to every pleasure even as we

rocked together toward the graying, even as

we held each other, warmth to warmth,

and said sorry, I’m sorry, I’m so sorry while petals

sifted softly to the ground all around us.

Catherine Pierce is the author of four books of poems including Danger Days and The Tornado Is the World and is professor of English and co-director of the creative writing program at Mississippi State University. (Photo: Megan Bean / Mississippi State University)

CURWOOD: Catherine, it sounds like you're in a way seeking permission to find beauty in, in what can happen during climate disruption, to, quote, "hold tight to every pleasure." How do you think allowing ourselves to see this beauty in the midst of this emerging disaster is vital for our emotional resilience?

PIERCE: I think it's crucial for two reasons. One is, I mean, as you say, it's, it's vital for our emotional resilience. If we're not able to take joy and pleasure in these moments as we find them, how can we possibly be strong enough to do what we need to do? Which is, which is the other part of why it's necessary, we need to be able to recognize this beauty so that we can try to save it. Right, we need to feel spurred to action by our relationship with this planet and with everything that it offers us. We need art, we need beauty, we need poems and walks in the woods and songs and essays, we need all these things, to allow us to feel the true pleasure that comes from paying attention to this world, which is just an absolutely remarkable place. But then we also need to feel strengthened by that into taking action, into trying to keep this amazing planet as something that our kids can explore with the same pleasure that we could, and that their kids hopefully can explore with the same kind of pleasure as well.

CURWOOD: Catherine Pierce is the author of Danger Days, The Tornado Is the World and other books of poems. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

PIERCE: Thank you so much for talking with me.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth