April 12, 2024

Air Date: April 12, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Supercharged Hurricane Season

View the page for this story

Some scientists are predicting this year’s Atlantic hurricane season will be extremely active as a La Niña develops amid ocean warmth linked to global warming. Meteorologist Ryan Truchelut of Weather Tiger joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the science behind these factors and how people along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts can stay safe. (10:58)

Big Cash for Clean Energy

View the page for this story

The Biden Administration EPA recently awarded $20 billion to organizations who will turn around and offer low-interest loans to help communities participate in the clean energy transition. EPA Administrator of New England David Cash and Host Steve Curwood cover how the program is catalyzing far more private capital and will help fund projects like insulating homes and replacing gas heating and cooking with heat pumps and induction stoves. (10:40)

From the History Books

View the page for this story

This week Living on Earth Contributor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood look back to a couple of big milestones in protecting species from human impacts, starting with when Starkist announced a shift to dolphin-safe tuna after an intrepid activist sparked a boycott. They also look back to the day the last wild California condor was captured as part of an intense captive breeding program that has helped the huge birds bounce back to around 400 today. (02:44)

The Solar Eclipse Takeaways

/ Jenni Doering & Aynsley O'NeillView the page for this story

The 2024 Great American Eclipse is now in the history books but still front of mind for Host Steve Curwood and Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill and Jenni Doering. They gather to swap stories about experiencing totality and shed light on some of the strange phenomena of the April 8 total solar eclipse. (05:18)

Poetry in the Time of Climate Troubles

View the page for this story

In her poems, Catherine Pierce grapples with unfolding climate disaster and other 21st century perils, and the ways they reframe parenting. She joins Host Steve Curwood to share poems from her books Danger Days and The Tornado Is the World, and to reflect on finding beauty and calls to action during the Anthropocene. (17:04)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240412 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: David Cash, Catherine Pierce, Ryan Truchelut

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Atlantic hurricanes could be supercharged this year.

TRUCHELUT: There's really two main predictors that you look at at this time range: is the Pacific going to be in an El Niño or a La Niña? And how warm is the tropical Atlantic Ocean? And right now, both of those factors are likely to be very favorable for highly elevated Atlantic hurricane activity in the 2024 season.

CURWOOD: Also, $20 billion to kickstart clean energy in local communities.

CASH: These sources of revenue from Congress and the Biden-Harris administration allow the private sector and individuals to convert to clean energy technologies, get cost savings, clean up the environment and create local jobs.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Supercharged Hurricane Season

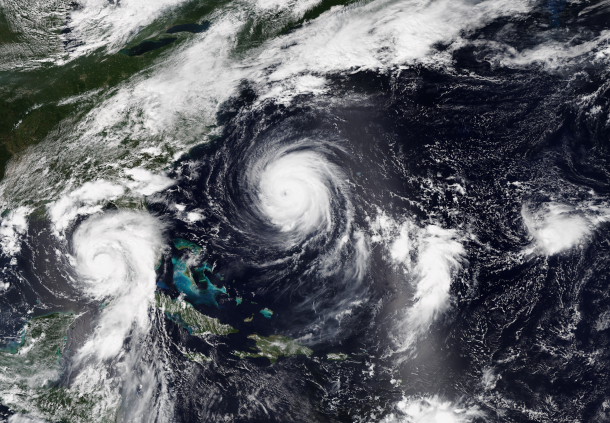

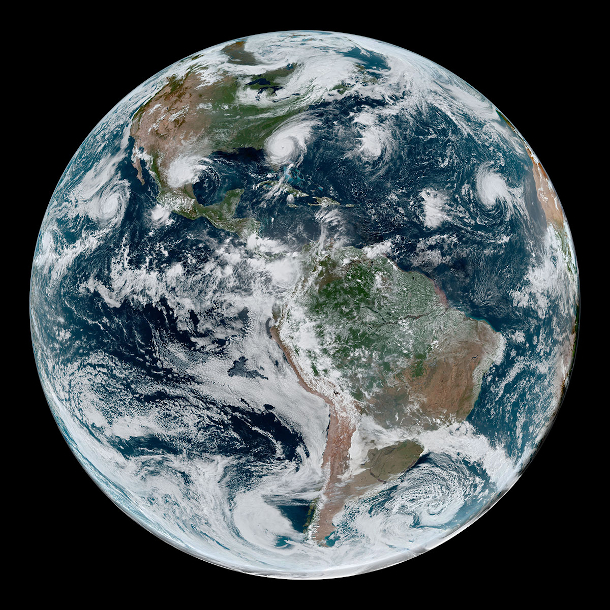

Three simultaneous tropical cyclones form in the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season. Idalia (left), Franklin (center), and what would eventually become Jose (far right). (Photo: S imagery from NOAA's NOAA-20 Satellite, NOAA View Global Data Explorer, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

If you live or work near the Atlantic or Gulf coasts, listen up: Some scientists are predicting this year’s hurricane season will be extremely active. They include Ryan Truchelut, the chief meteorologist at Weather Tiger in Tallahassee, Florida, and he’s on the line now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Ryan!

TRUCHELUT: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So, in June, the formal start of the Atlantic hurricane season begins. Look into your crystal ball, what are the indicators that you see that can give us a good prediction for this coming summer when it comes to those hurricanes?

TRUCHELUT: Well, when you're making a forecast for the hurricane season overall activity in March or April, there's really two main predictors that you look at at this time range. And those are, is the Pacific going to be in an El Niño or a La Niña? And how warm is the tropical Atlantic Ocean? And right now, unfortunately, both of those factors are likely to be very favorable for highly elevated Atlantic hurricane activity in the 2024 season.

CURWOOD: Hmm. Sea surface temperatures are hotter. How much hotter?

TRUCHELUT: Well, they've really been breaking records here as we've gone through winter 2023-24. They were very, very hot during the 2023 hurricane season, and they never really cooled off. So the average temperature in the tropical Atlantic, kind of the region that we watch for hurricane development as the season rolls forward, has been about a third to half a degree warmer than it ever has been previously in a northern hemisphere winter.

CURWOOD: It's changing now from the El Niño to the La Niña, as you say. What does that do to hurricanes?

Hurricane season 2024 outlooks are calling for a hyperactive season. However, it's still too soon to confidently predict U.S. impacts.

— WeatherTiger - weathertiger.substack.com (@wx_tiger) April 4, 2024

Our analytics show a >90% chance of a top tercile ACE season, but only a ~55% chance of top tercile season from a U.S. landfall perspective. pic.twitter.com/CQqp1n8u2i

TRUCHELUT: Well, unfortunately, that is also very favorable for hurricane development in the Caribbean Sea, the western Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico. And the way that that matters, people often ask me, you know, why does it matter what's happening in the Pacific, we're looking at the Atlantic. Well, El Niño and La Niña really set the tone for weather patterns worldwide. When the waters of the Central Pacific near the equator are warmer than average and we're in an El Niño, that results in a weather pattern that results in unfavorably strong upper level winds over the western Caribbean and the western Atlantic that are unfavorable for hurricane development. So when there is an active El Niño, the Atlantic hurricane season tends to be quieter than normal. In La Niña, when the waters of the Central Pacific near the equator are cooler than average, it's just the opposite. Those upper level winds are lighter than average over the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. That's favorable for tropical storms to develop and intensify. And unfortunately, that means it's often a busier than average hurricane season in the Atlantic when a La Niña is going on.

CURWOOD: Now, last year, we had the El Niño and still there was some pretty tough hurricanes that hit the Gulf of Mexico, Florida. So, it sounds to me with La Niña switching on, it's like adding steroids to the system.

TRUCHELUT: Right. Last year, the 2023 hurricane season was a real conundrum for hurricane forecasters, because we'd never faced such a divergence in those two key predictors. Atlantic sea surface temperatures were very, very warm. Record warmth, far above average. But at the same time, we were looking at the development of a pretty strong El Niño in the Pacific. So there was a real question in the hurricane research community and hurricane forecaster community of which of those influences was going to win out. And in the end, it was a busier than average hurricane season, it was about a third more active than average. Fortunately, most of that activity stayed out to sea in the central Atlantic. But as you point out, I'm in North Florida. So we had to deal with a threat from Category Four hurricane Idalia in late August. It's very unusual for the Gulf Coast to be threatened by a Category Four hurricane during a strong El Niño year. But it's that offsetting Atlantic warmth that really gave some of the storms an extra boost last year.

CURWOOD: And now we're going to move into a situation where those accelerators, those additive factors are coming together. Warmer ocean and a La Niña. Ryan, if you wouldn't mind, just crack open your history book for us for a moment. Talk to me about some of the past years that have had similar conditions to the ones that you're seeing for this upcoming 2024 season. How did those years fare?

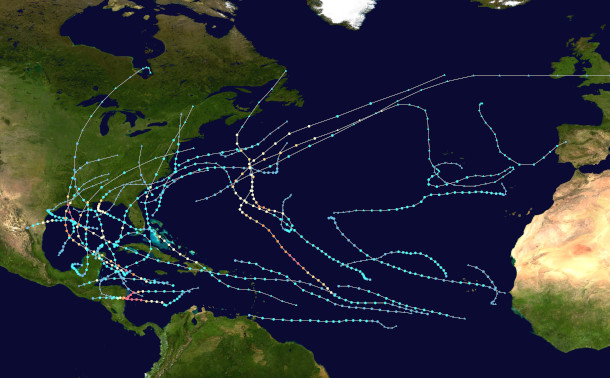

A map tracking all the tropical cyclones in the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season. With similar conditions of very warm tropical Atlantic Ocean temperatures and a peak season La Niña, 2020 is a good indicator of how much hurricane activity the Atlantic is likely to see in 2024. (Photo: MarioProtIV, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

TRUCHELUT: Well, in the past few decades, we do have a couple other years that we can use as reference points. The key ones are 1998, 2010, and 2020. In all three of those seasons you started out the year with an ongoing El Niño. That El Niño weakened and dissipated by the summer months and was replaced by a La Niña in the fall. The Atlantic sea surface temperatures were also warmer than average in those key development regions in each of those three years. Now not quite as warm as we are right now in 2024. But certainly warmer than average. All three of those years were significantly more active than a normal Atlantic hurricane season. More active by about 75%. So, all three of them had essentially the same amount of overall activity. But if there's something that's a little bit comforting to take away from this, it's that those three years had very different outcomes in terms of impacts on the continental United States, as well as populated areas bordering the Caribbean and in Central America and Mexico. In the 1998 hurricane season, the United States saw three hurricane landfalls, but no major hurricane landfalls. We did see Hurricane Mitch, which was a horrible storm for Central America, one of the worst of all time in the Caribbean. In the 2010 hurricane season we saw next to no impacts in the continental United States. We did see some hurricane landfalls in the Caribbean and in Central America, but it was a light year for the United States even though there were a lot of hurricanes out in the open waters. Unfortunately, in 2020, that was a very, very busy hurricane season. Not only did we have the most named storms ever on record, with 30, but we saw seven major hurricanes, and numerous landfalls along the Gulf of Mexico coast, including Category Four Hurricane Laura. And we also saw horrific storms in Central America going into October and November of that year. We had Eta and Iota off the Greek name list that just pummeled Central America deep into November. So there's a range of outcomes still on the table. Just because it's an active hurricane season doesn't necessarily mean that it'll be a very busy one for the United States. But it certainly does raise the baseline risks when there's more activity.

CURWOOD: Looks like conditions are right for a hyperactive season this year. What will meteorologists, folks like you, be watching out for as we get closer to June?

Putting those together, that means 2024 is going to be in rare company, among just 8 other years since 1950 to have a cool Pacific and very warm Atlantic.

— WeatherTiger - weathertiger.substack.com (@wx_tiger) March 22, 2024

Six of these eight years were "hyperactive" Atlantic hurricane seasons, with 60-150% more activity than normal. pic.twitter.com/kYrMTWjMG1

TRUCHELUT: Well, we'll be watching to see if there's any changes in the depth or the extent of that warmth over the tropical Atlantic. Those sea surface temperatures can change with time. They can warm up, they can cool down. They can pivot pretty quickly as trade winds shift. So I will say it's going to be difficult to pull back the warmth. We're so far above average that even if they cooled off, we have a lot of cushion and we'd still probably be well above average for the season, heading into the peak of the season, even if we don't warm up quite on the rate that we have been. And we'll also watch to see how La Niña is developing in the Pacific. Right now, there's every indication that El Niño will be ending over the next month or so. And we'll be proceeding pretty quickly through neutral conditions and then into La Niña by the end of the summer. But if that changes, if there's a delay or we don't see La Niña developing quite as quickly as many of the models now suggest, that, too, would change the risk profile somewhat. So, you know, overall, kind of the way that I phrased this in my seasonal outlook is that we're very likely to have an above average hurricane season. That's almost baked in at this point. But we don't know are we going to have a size L hurricane season or are we going to have a size XXXL? How many extra larges are we going to have in terms of impacts? That's still up in the air.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about what those who are in the hurricane parts of the world should know in preparing for a season with this elevated risk.

TRUCHELUT: Well, people who live along the coast need to have a plan for what they would do if a major hurricane is heading in their direction. And when, once the watches and warnings go up, once you receive evacuation orders from local emergency management, you need to know what you would do in that circumstance, where you would go. Now in many cases, when you receive an evacuation order, you don't need to flee to another state. You just need to move far enough inland so that you're above the dangerous floodwaters and surge waters that are occurring along the immediate coastline. So know your surge zone, know your evacuation zone and be ready with a plan to heed that order when the time comes. Because that will save your life. You can hide from wind, but you need to run from water.

CURWOOD: The media often focuses on the speed of the hurricane. OMG, it's a Category Four, it's a Category Five, but I gather from your work the storm surge is a much bigger risk to people. Talk to me about that, please.

Ryan Truchelut is co-founder, president, and chief meteorologist at WeatherTiger. (Photo: Courtesy of Ryan Truchelut)

TRUCHELUT: That's true. For a long time we focused on wind. Wind is how we categorize and classify hurricanes. The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale is completely based on the maximum sustained wind. Now, maximum sustained wind only occurs in a tiny sliver of a hurricane’s eyewall. And it really, that maximum wind is only occurring offshore. Anytime a hurricane moves over land, just the friction between the wind and the trees and the buildings slow down those maximum sustained winds. So that's really not the right focus to have as we're kind of holistically evaluating the total threat that a hurricane poses to life and property. Now, wind is a serious risk. I don't want to play that down. It certainly does quite a bit of damage when a major hurricane makes landfall, but only about 10% of the deaths and casualties in a hurricane are caused by wind itself. The vast majority of damage and casualties are caused by flooding and storm surge flooding, river flooding, excessive precipitation, as well as the wind pushing those waters on shore. So as hurricane forecasters and risk communicators, science communicators, we're kind of trying to move away from the category of a storm and kind of think about all the different threats that a hurricane poses, whether it be wind, surge, flooding or tornado threats.

CURWOOD: Okay. Ryan Truchelut is chief meteorologist at WeatherTiger in Tallahassee, Florida. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Ryan.

TRUCHELUT: Of course. Thank you. Anytime.

Related link:

WeatherTiger | “Atlantic Hurricane Season First Look: March 2024”

[MUSIC: Emmet Cohen “Dardanella”, Mack Avenue Records II]

CURWOOD: Just after the break, massive federal funds to help people have cleaner air and water while fighting climate disruption. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Rikard From “It’s an Upright Thing”]

Big Cash for Clean Energy

The Environmental Protection Agency has awarded grants -- ranging in the hundreds of millions to billions of dollars -- to eight nonprofits that will loan the money to clean energy projects. (Photo: US EPA, Flickr, Fair Use)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

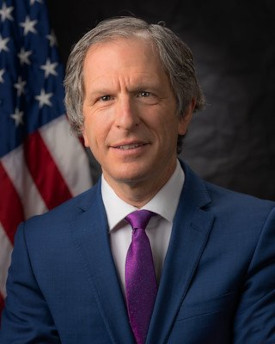

As part of the bid by the Biden administration to fight climate disruption, the Environmental Protection Agency recently awarded $20 billion to help finance clean energy projects across the United States. The money is part of the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, created under the Inflation Reduction Act. Unlike a typical grant program, the EPA will not fund projects directly. Instead it is providing grants to select organizations who will turn around and offer low-interest loans in communities that need them the most. The $20 billion in federal funds are expected to stimulate as much as $150 billion more in private capital to advance the clean energy transition. Here to explain is David Cash, Administrator of EPA's New England Region. Administrator Cash, welcome back to Living on Earth!

CASH: It's great to be on the show, Steve.

CURWOOD: Tell me, what sort of work went into building this grant program?

CASH: Yeah, so the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, this is just one of the many, many different efforts that the EPA and the Biden-Harris administration is making to address the climate crisis and to grow the clean energy economy here and to reduce energy costs for people all over the country. So this is just one piece of that. And it was created in President Biden's Inflation Reduction Act. And with the program, EPA is creating a first-of-its-kind national network of mission-driven, community-led, financial institutions. So you could think of these institutions that says, creating, you know, loan funds that can go out to communities that will finance climate, clean energy projects, and especially in low-income and disadvantaged communities.

CURWOOD: So I gather there are a couple of parts of this process. What are they?

CASH: Sure, so there are three big parts of the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. The first I'm not going to talk about, it's the Solar for All program, $7 billion. We haven't made a final announcement on that, that's coming probably later in the spring. But the two big pieces that were announced are the National Clean Investment Fund, that's $14 billion, and the Clean Communities Investment Accelerator, that's another $6 billion, so $20 billion dollars. And the first one, the National Clean Investment Fund, it has three selected applicants, and those will create funds, partnering with the private sector to provide accessible, affordable financing for tens of thousands of clean energy projects nationwide. So enabling individuals, families, nonprofits, governments, businesses to access capital in a way that they haven't been able to before. We know that there has been underinvestment in this country in clean energy, clean technology, clean deployment. And that's what this is designed to do.

The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) was authorized by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) largely for clean energy and energy efficiency projects. Among the programs is Solar for All which will award up to 60 grants to expand the number of low-income and disadvantaged communities primed for residential solar investment. (Photo: Jonsowman, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Give me a couple of examples of what this might finance.

CASH: Sure. So let's say, for example, there is like an affordable housing provider that's rehabilitating a 50-year-old, 200-unit, Section 8 rental property. We know these are all over the country, these kinds of affordable housing projects. And they may be short on financing to fully electrify the building, to get them up to a way where they'll be as energy efficient as possible. So the funds can then help finance that network. And the affordable housing provider can be able to turn to that network and fill the specific financing gaps for these kinds of projects. And let me bring this down to the really personal level. We visited a public housing unit in Boston where we met with some of the tenants who showed us the gap underneath their door that they said snow blew into, they showed us windows that didn't close completely, they showed us old appliances that were incredibly energy inefficient. This kind of funding is going to be able to rehab that apartment to make sure that that family is comfortable, pays less for their electric bill, has new appliances, and is part of the clean energy future. And we see these funds, these $20 billion, leveraging private funding in like a seven-to-one ratio, about $150 billion for a $20 billion investment roughly. It's going to be huge.

CURWOOD: And let's talk about the other part then.

CASH: Sure. So the Clean Communities Investment Accelerator, those are designed to establish hubs to provide funding and technical assistance to community lenders. And working primarily all of those, that $6 billion, is going to low-income and disadvantaged communities. By the way, a large section of that prior one I mentioned to you, the 14 billion, is also going to low-income and disadvantaged communities. Those communities, by the way, who have suffered under the burden of pollution in the last decades. And in fact, those communities that have been dependent on the fossil fuel economy, but have seen that waning. And so these are funds that can go out to those communities and create a new clean energy economy and jobs and investments there as well. And you know, one of the things about this is we've often heard from federal government that federal government can be top down. These programs are designed to be bottom up, to respond to the needs of communities so that communities are driving where investments go.

Appalachian Community Capital, a nonprofit CDFI working with community lenders in Appalachia, is slated to receive a $500 million award and plans to launch the Green Bank for Rural America. (Photo: Ted Auch, Flickr, FracTracker Alliance, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So how can these communities get access to these funds? Typically, more affluent communities have people who know how to write grant proposals and work the government system. If you're living in public housing where the snow is blowing under the door, it’s unlikely that you have kind of the intellectual capital to navigate the system. So how do you get folks who need it to get plugged into the system?

CASH: Yeah, so here's one of the things that was brilliant about the way that our team in headquarters structured the competition process for these. Each of the winners have had to articulate how they are going to connect precisely with the community lenders, such as community development, financial institutions, credit unions, minority depository institutions, how they're going to connect with those, so that when you have a household, or even a community organization, they're already going to be tapped into the network. So that communicating about the availability of these kinds of funding opportunities, these kind of revolving loan funds, will be made more and more apparent to those who precisely need it. You know, in fact, what I mentioned to you before about communities that have depended on fossil fuel economy, one of the hubs is going to be the Appalachian Community Capital, a nonprofit CDFI, which has a decade of experience working with community lenders and Appalachian communities, so they know who to go to. And similar on the tribal side, so tribal communities will know where to go.

CURWOOD: For folks who don't know, what's a CDFI?

CASH: Yes, so it's a community development financial institution. So you can think of it as a lending institution, a bank that is closely connected to communities that otherwise would have a difficult time raising capital. Unlike what you had said, you know, in your relatively wealthy community, there's going to be a lot of understanding about how to access this capital and these CDFIs go a long way toward creating that capacity in these communities.

CURWOOD: So if you were to summarize, what are the environmental issues that these grant programs are seeking to redress?

David Cash is the Administrator of EPA's New England Region. (Photo: Courtesy of the EPA)

CASH: Clearly the climate crisis. We know that we need to take action on that, and urgent action. So these investments are going to go a long way in reducing emissions that cause climate change by deploying solar and wind, electric vehicles, by doing energy efficiency, which in many cases is by far the cheapest way to reduce emissions. So that's one. The other is addressing local air pollution. Again, we know, whether it's through power plants, or manufacturing facilities, or buses, or trucks or cars, that local air pollution is a huge problem and a huge problem in communities that have been overburdened by these pollutants for decades upon decades. And then on the water side, we see the replacement, for example, of lead pipes as incredibly important for communities that have relied on the old housing stock. So we see a lot of that in New England, of course, where we have buildings that are, you know, 100-plus years old, we're gonna find a lot of lead pipe. And we know that lead is particularly damaging to children. And so President Biden has a goal to get rid of all lead pipes in the next 10 years. And there's billions of dollars that are in the bipartisan infrastructure law that's going to address that. And of course, it goes hand in glove with creating new clean energy jobs, whether it's to put on a solar panel on your roof or replace the windows or put in heat pumps, you know, those are all opportunities for huge job growth.

CURWOOD: So how excited are you about this $20 billion and this program that you and the folks at the EPA are now administering?

CASH: Yeah, so it's interesting, EPA had grant programs and got money out the door, but nothing, nothing on the scale of what we're doing now. And it's incredibly exciting, because we're at a moment where it's both incredibly urgent that we take action and we have huge opportunities. And so to be part of an agency that is going to be providing funding in the way that we're providing, lifting up communities, helping them identify what they need, where they want the investments to be, so that they can reduce their costs, so that they can breathe cleaner air, so that they can be part of the clean energy job growth. I mean, that's incredibly exciting. And for this project to be just part of one of many that EPA, the Department of Energy, Department of Commerce are working on to get these kinds of results. Very, very exciting, Steve. This is, you know, I wake up every morning and, you know, basically I skip to work.

CURWOOD: Well, I want to thank you, David, for taking this time with us today. David Cash is Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency's New England region. Thanks so much.

CASH: It's been a pleasure, Steve, thank you so much, and it's an incredibly exciting time to be talking about this. Thanks.

Related links:

- The Washington Post | “America’s New High-Risk, High-Reward $20 Billion Climate Push”

- Learn more about David Cash the Administrator of EPA's New England Region

- EPA | “Summary of Inflation Reduction Act Provisions Related to Renewable Energy”

[MUSIC: Elton John, “Crocodile Rock” on Don't Shoot Me I'm Only The Piano Player, by Elton John, This Record Company Ltd.]

From the History Books

StarKist began purchasing tuna only from fishing companies that used dolphin-safe fishing practices after a boycott of their product. (Photo: Mike Mozart, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: On the line now from Atlanta, Georgia is the one and only Peter Dykstra, Living on Earth contributor and now a historian for us today. What do you see in the history books, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. April 12, 1990, a red letter day thanks to a green activist, the StarKist brand announced it will no longer buy and sell tuna that's caught by methods that also cause the deaths of thousands of dolphins each year.

CURWOOD: And what was that method?

DYKSTRA: It's called purse seining. The fishermen would use nets that look like a gigantic string purse. They'd find tuna and literally draw the purse strings around a huge school of tuna. Many dolphin species associate with the tuna, were caught up in those nets and literally drowned. Not only were there tuna killed this way, but thousands of dolphins. It was causing an immense problem.

CURWOOD: So how did this come to light? Who's the green activist?

DYKSTRA: Sam LaBudde crewed as a cook aboard a tuna seiner. He did so at the risk of his own life. And what he did was videotape dozens of dolphin carcasses being hauled in with the tuna. That was shown. It prompted a boycott of the tuna industry. And StarKist executives, just before Earth Day were swayed. They decided to convert to what they called dolphin-safe tuna, and no longer used that purse sein method. LaBudde's courage won him the Goldman Environmental Prize the following year in 1991.

CURWOOD: Hey, Peter, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: On April 19, 1987, the last California condor believed to be alive in the wild, named AC9, was captured. Over the next 20 years, an intense captive breeding program brings the species back from the brink of extinction. They were nearly wiped out by habitat destruction, DDT use, and other threats. There are now over 400 California condors alive, nearly half of them rereleased into the wild, a real victory in saving a gravely endangered species.

Conservationists saved the California condor from extinction via a captive breeding program. (Photo: Wade Tregaskis. Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: That's such a great story, Peter. Let's just hope that we can do that with other species that are on the brink.

DYKSTRA: Well, we have with some and we will.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is a contributor to Living on Earth, and we'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth webpage. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- Read more about Samuel LaBudde’s Goldman prize win

- Learn more about efforts to save the California condor

[MUSIC: Postmodern Jukebox-Featuring Ashley Campbell, “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” on http://pmjlive.com/rizz and on "Puttin' On The Rizz", by Paul Simon, Mud Hut Digital/Concord Records]

The Solar Eclipse Takeaways

Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering, Steve Curwood, and Aynsley O’Neill all got a chance to see the total solar eclipse in the Northeast. Jenni Doering’s friend, Tina Chen, took this picture of the moment of totality. (Photo: Tina Chen)

CURWOOD: Well, it's been a few days since the total solar eclipse, but we're still taking it in, and with me now are Living on Earth's Jenni Doering and Aynsley O'Neill, here to share their experiences and reactions. Jenni, tell me, what happened to you when you were chasing this eclipse?

DOERING: Hi, Steve. Yeah, wasn't this amazing? We had beautiful weather. I went up to New Hampshire, a little town called Colebrook. It's right along the Vermont border. The Connecticut River is the border. And you know, despite all of the crowds on the way to the eclipse and coming back, it was so worth it.

CURWOOD: And what about you, Aynsley?

O'NEILL: Yeah, I had an awesome time; a group of friends and I road-tripped up to Vermont. We found this little town called St. Johnsbury, which was supposed to have beautiful clear skies and boy, did it! And so we were able to stretch out on this baseball field with a couple of other groups of people. One nice family even let us use their filtered telescope, which was really awesome. And it was just a really cool time to come together with all these people.

Producer Aynsley O’Neill (right) stands in a baseball field in St. Johnsbury, Vermont to eclipse-watch with her friends. (Photo: Gabe Trotz)

CURWOOD: Yeah, I went pretty close to where both of you were, also in northern New Hampshire, a little town called Errol. St. Johnsbury is just across from Lancaster in northern New Hampshire. I don't think they'd seen as many people there in probably the whole last century. But we were part of a nice, large, friendly crowd behind a furniture store. Some folks had turned it into tailgating, they had grills and everything going, even though of course, it's mud season this time of year.

DOERING: Oh, yeah.

CURWOOD: And when the totality hit, I spotted some bats flying--

O'NEILL: Whoa.

CURWOOD: --at three in the afternoon.

DOERING: Oh, that's cool.

O'NEILL: Oh, there was nothing like totality. It was so cool to see the sort of night come on so quickly. I saw Venus and Jupiter really bright in the sky. But I wish I had been able to see some stars too.

DOERING: I saw a few stars. I saw the planets, and did you see the ground rippling?

O'NEILL: The rippling? No.

Managing Producer Jenni Doering (second from right) and her friends watched the 2024 total eclipse from Colebrook, New Hampshire. (Photo: Courtesy of Jenni Doering)

DOERING: So, there were these like shadows moving across the lawn where I was. And I saw other people noticing this too, and like kind of pointing and gaping at it. And I Googled it later, I guess it's called shadow bands. And scientists don't even know really what causes this. But they think that it is basically when the sun is down to this tiny sliver, that the rays of light are moving through the turbulence in the atmosphere and getting distorted. And kind of similar to what makes the stars twinkle.

O'NEILL: Well, I mean, the whole time leading up to and leading away from totality was pretty cool, too. I thought it was so interesting how the color sort of sapped from the landscape. What I found out is that your eyes are stopping using the cones as much and starting to use the rods. So longer wavelength colors like red are starting to dim, and shorter wavelength colors like blue and green are starting to pop. And because it happens so quickly during the eclipse, it's really kind of surreal, and everything looks kind of metallic.

CURWOOD: Yeah, but there was some red, actually, it was in the corona of the sun there—bright red spots along the edge of the disk. I wondered if they were solar flares. But then someone in the crowd mentioned prominences?

DOERING: Yeah, Steve, those were so bright, I was honestly worried that they were going to hurt my eyes. So I kept putting my solar glasses back on, just to check. But I read that they're actually part of the sun's super hot plasma that kind of arcs out following the powerful magnetic fields that the sun has. And unlike a solar flare, they kind of stay attached instead of flinging off into space.

CURWOOD: Yeah, this is really, of course, a huge, extremely powerful fusion reaction that we were watching there, hydrogen getting fused into helium, there's a ton of energy. So as totality came on, the temperature went down, and we had to put on our sweaters.

DOERING: Us too!

O'NEILL: Oh, it got chilly!

Executive Producer Steve Curwood captures totality in Errol, New Hampshire. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

DOERING: It was weird. The sun was like, visibly weakening, noticeably weakening. I guess researchers were expecting some solar energy production drop as a result of this eclipse. So the National Renewable Energy Lab, NREL, they predicted that it might drop by as much as 35 gigawatt hours along the path of the eclipse.

O'NEILL: Ooh, it's going to be interesting to see all this data coming in. Even with just a couple of minutes of totality, I'm sure so much science was being done. Although, you know, we only had a couple of minutes, but there are ways to get more than a couple of minutes. I found out that in 1973, a group of scientists chartered a supersonic Concorde jet to chase the eclipse. They got something like 70-plus minutes. I am so jealous!

DOERING: That's a long eclipse!

O'NEILL: That's a long eclipse.

Steve Curwood’s group braved the mud to watch the eclipse. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: And well, so what about chasing eclipses? When's the next one?

DOERING: Yeah, so I guess there's an annular one coming up this October. But what that means is that the moon is farther away. And so it's actually not big enough to block out the entire sun like this eclipse was.

CURWOOD: Hmm, so I guess any eclipse chasers or umbraphiles, as they are sometimes called, will need to wait until August of 2026 and travel to either the Arctic or Western Europe to catch a glimpse.

O'NEILL: And since it's not going to be in the US, a couple of us might be looking to hang up our eclipse glasses, and you can find out more about how to donate them on our webpage, loe.org.

CURWOOD: Well, science is always interesting, but who knew that science could be so much fun?

DOERING: A lot of fun—and really memorable.

O'NEILL: And really enjoyed in a crowd. That was awesome.

Related link:

NASA | “2024 Eclipse: Where and When”

[MUSIC: The Beatles, “Here Comes The Sun – Remastered 2009” on Abbey Road (Remastered), Apple Corps Ltd]

CURWOOD: Coming up, poetry in the time of climate troubles. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jackie McLean, Herbie Hancock, “Yams” on Vertigo, Blue Note Records]

Poetry in the Time of Climate Troubles

Poet Catherine Pierce confronts the climate emergency head-on in her work, and even finds beauty within it. (Photo: Catherine Pierce)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

The climate crisis is picking up pace, with important heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere at record levels in 2023, which was also the warmest year on record in modern times. And as we heard earlier in the show, forecasters are predicting a busier than usual hurricane season this year thanks in part to warmer than ever sea temperatures. Science can help us understand our disrupted world, but poetry can also enlighten us. So as Poetry Month continues, we turn to Catherine Pierce, Poet Laureate of Mississippi. Her poetry collections include Danger Days and The Tornado Is the World. Catherine Pierce, welcome to Living on Earth!

PIERCE: Thank you so much for having me on.

CURWOOD: Our pleasure. So Catherine, environmental disaster seems to be, well, can I call it a muse of sorts for you? Tell me, tell me why is that?

PIERCE: [LAUGHS] That's a great question, a muse! Yeah, I guess, I mean, I guess we could call it that. It's a terrifying muse, but I guess we could call it that. I've become increasingly impacted, just in my day-to-day life, by extreme weather, by these things that are changing, in the way that I think a lot of us have. I live in Mississippi and we've had, you know, more and more tornadoes, tornadic weather, strong storm systems coming up through the Gulf. And people's lives have just been completely disrupted and sometimes destroyed by these things. And so that's part of it, is having had some very real experiences, very close calls with tornadoes, and knowing a lot of people who have had homes destroyed, or who have lost loved ones because of these things. And I also became a mother while I was living in Mississippi, I have two kids, and we try to get outside a lot, we try to experience the outside world as much as we can. And it's a thing that brings us a lot of joy. But there's something about trying to impart that joy to my children; it's always kind of tinged with this sadness, or this feeling of guilt as I think about how this world as we know it is shifting every single day. And what's going to be left by the time they're my age?

Photomontage of the evolution of a tornado: Composite of eight images shot in two sequences as a tornado formed north of Minneola, Kansas on May 24, 2016. (Image: JasonWeingart, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: Now, if you grew up near the Chesapeake, then you must have been well aware of nature as a child, as a young person coming up. What's changed about your perception of the environment now, as an adult in these times of climate disruption?

PIERCE: I mean, one thing that I've noticed is the fact that small things are different. Things like the fact that when I was growing up, we had snow pretty regularly, you know, up in Wilmington, Delaware, where I grew up. And now there's less of that. I mean, we're getting extreme snow, we're getting crisis snow. But we're not getting as much of that sort of reliable, pleasant, you know, several inches, close-the-school-for-a-day kind of snow. And so you know, you see these little changes. Or I see things like, I teach at Mississippi State, and we have this beautiful campus with all these beautiful blooming trees. And a couple of years ago, I remember walking outside and seeing that one of our trees near the English building was blooming, but it was the fall, it was a tree that should be blooming in the spring. And the tree was confused, something about the weather had, had confused it. So and you know, you see these things occasionally. And then thinking about just extreme weather popping up throughout the country, the tornadoes that are getting increasingly bad in the Deep South, and also in the Midwest; the extreme weather that we saw in Texas not so long ago. All these things, all of this extreme weather that's coming through, all as a result of disruption and of climate crisis. And these are things that, you know, again, I'm observing from the perspective of just a person, you know, living my life. And I'm not a meteorologist, I'm not a scientist, but I'm paying attention. And I'm aware of the way the sun feels on my face. And I'm aware of the way the wind feels when I step outside. And they're subtle shifts, but they're very real, and if you look at the data, all the stats are there. But I think we can see it in very day-to-day ways as well.

CURWOOD: You have a poem that I'd like to ask you to read that really seems to capture, well, kind of the element of, of exhaustion of dealing with constant climate disruption now. It's called, If/When.

On Sept. 4, 2019, a chain of tropical cyclones lined up across the Western Hemisphere. (Image: NASA Earth Observatory/Joshua Stevens; NOAA National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service)

PIERCE: Yeah, this poem was first published in the Southern Review.

If/When.

The poem I planned to write

was about last week’s hurricane,

about how I live in Mississippi,

not that far from the storm’s rages,

and how even still we felt

nothing here, nothing at all.

That was going to be the ending,

because I wanted to make a point

about how easy it is to ignore

disaster when it’s not churning

directly over your town, and I was hoping

a reader might then extrapolate

a larger point about disturbance

and proximity, like how politicians

are always saying they used to oppose X

until some terrible Y happened

to their daughters, and it seems

to me we’re requiring an awful lot

from daughters these days. Sons, too.

This week a message from my kids’

school district included the phrase if/when

a lockdown is ever necessary. The reason

I’m writing this poem instead

of the one I’d planned is that I keep

thinking about that email and also

now the hurricane was a week ago

and there’s a new disturbance

forming near the Bahamas. And

last night Sioux Falls was tornado-

shredded and in Sterling, Colorado,

egg-size hail pummeled windshields,

and I guess what I’m saying is, why bother

with one poem about one hurricane,

one email? There will be more,

and there will be more,

and there will be more until

there is nothing left. The thing

about the poem I was going to write

is that it would have been a lie.

That nonsense about how we don’t

feel it here. We feel it everywhere,

don’t we? Dear daughter, dear son,

dear someone’s something, we’re well

past the if and into the when.

Talk about proximity—

some days I wear the world

like a skin. I am tired of waiting

for extrapolation. Let us all

be disturbances now.

CURWOOD: Yeah. So what are the climate impacts that have made perhaps the deepest impressions on you?

PIERCE: Certainly, for me, it's been the tornadoes that I've seen living in Mississippi. And we see tornadoes every year, we have tornado warnings regularly in the spring and fall especially. And, you know, the sirens go off, and everyone's in their bathtubs, because we don't have basements there because the, the water level is too high. So everyone just hunkers down in their bathtubs and hopes for the best. But that for me has had a huge impact. In 2011, that was when the tornado super outbreak occurred, if you remember that, that really decimated a lot of the Deep South. More than 300 people were killed that day, and thousands more were injured. And on that day, I happened to be traveling with my husband and our infant son—I had just had my first son, he was four months old—and we were driving. We knew the weather was supposed to be bad, but we didn't really have a sense of things exactly. And this was before we had smartphones, so we couldn't really check anything, we just had the radio on as we were driving. And we got to Cullman, Alabama, and saw that the sky looked really bad and really strange. And so we pulled over and went into a Days Inn. And soon as we got inside, some people came running in saying, it's out there, the tornado was coming. And so we all, me and my husband and our son, and the few people in the lobby, we all ran into the bathrooms because they were the most interior rooms off the lobby. And we all just kind of hunkered down there. And I just remember people screaming, and the power went out. And I mean, it was definitely the scariest single moment of my life, and we were all pretty sure we were going to die. And we didn't, obviously; and the tornado did not hit the Days Inn where we were, although it did hit Cullman, and several people were killed, and many more were injured. But we were very lucky. And that experience crystallized a lot of things for me about weather and climate, but also about being a parent, and being a parent who writes poems. And that experience became the catalyst for the book that I went on to write, which was called The Tornado Is the World, and became sort of a lens through which I could explore parenthood, which was new for me, and which I didn't quite know how to write about yet. And so I did, I developed a series of personae in that book and used those and sort of created a narrative of people dealing with the aftermath of an EF4 tornado, which was what that tornado had been.

Pierce composed the poems in The Tornado Is the World in the aftermath of the 2011 Super Outbreak that left a swath of destruction through Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee and other states. (Image: Courtesy of Catherine Pierce)

CURWOOD: So, why don't you read one of your tornado poems for us?

PIERCE: Sure. And this was the first poem that I wrote after that tornado experience. And so this is the one that is pretty autobiographical, at least in terms of what I was feeling in that moment. And in the book, the tornado takes on its own persona, because to me, it always feels like a tornado has agency. I always feel like it's making a decision about what it's doing, somehow. And so this poem addresses that. It's called The Mother Warns the Tornado.

I know I’ve already had more than I deserve.

These lungs that rise and fall without effort,

the husband who sets free house lizards,

this red-doored ranch, my mother on the phone,

the fact that I can eat anything—gouda, popcorn,

massaman curry—without worry. Sometimes

I feel like I’ve been overlooked. Checks

and balances, and I wait for the tally to be evened.

But I am a greedy son of a b****, and there

I know we are kin. Tornado, this is my child.

Tornado, I won’t say I built him, but I am

his shelter. For months I buoyed him

in the ocean, on the highway; on crowded streets

I learned to walk with my elbows out.

And now he is here, and he is new, and he

is a small moon, an open face, a heart.

Tornado, I want more. Nothing is enough.

Nothing ever is. I will heed the warning

protocol, I will cover him with my body, I will

wait with mattress and flashlight,

but know this: If you come down here—

if you splinter your way through our pines,

if you suck the roof off this red-doored ranch,

if you reach out a smoky arm for my child—

I will turn hacksaw. I will turn grenade.

I will invent for you a throat and choke you.

I will find your stupid wicked whirling

head and cut it off. Do not test me.

If you come down here, I will teach you about

greed and hunger. I will slice you into palm-

sized gusts. Then I will feed you to yourself.

Debris and damage from the EF4 tornado that hit Cullman, Alabama on April 27, 2011 while Pierce and her family sheltered inside a Days Inn. (Photo: WildBamaBoy, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: How fair is it to say that the climate has given you PTSD?

PIERCE: Oh, very fair. [LAUGHS] I think that following the tornado experience, that was something that I hadn't realized that was what I was kind of working through in writing those poems. But it, but it was, and a lot of those poems deal very directly with that, with that feeling of not being able to see the world the way that you saw it prior to this event.

CURWOOD: And as a mother, how do your kids shape your writing about something that, well, it's in the process now of impacting their lives, and it'll be with them for a long, long time?

Danger Days, Pierce’s latest book of poetry, confronts climate disruption and other 21st century perils while bearing witness to the beauty in their midst. (Image: Courtesy of Catherine Pierce)

PIERCE: Absolutely. Well, so I, my book Danger Days came out in October of 2020. And that book deals a lot with climate crisis and a lot with parenting through climate crisis, and thinking about ways that I can try to, you know, hold these two ideas simultaneously. The idea of being afraid and angry and trying to take action on behalf of the planet; and genuinely celebrating and finding joy in all the marvels of our planet. And trying to impart that to my kids, trying to say, Yes, let's go out, and let's find these beautiful things. And look, there is a blue heron, and oh my gosh, let's find out what kind of flower this is. And so trying to kind of find that balance of not wanting to frighten my kids, but also wanting them to be informed, while still finding genuine joy in our amazing planet and all it has to offer.

CURWOOD: Catherine, there's another poem of yours that grapples with what some might even see as beauty in climate disruption. It's called Anthropocene Pastoral. Could you read that for us and set it up for us as well?

PIERCE: Absolutely. So this poem is called Anthropocene Pastoral, and I wrote it following the California superbloom of 2017, when the deserts in California were covered in just these gorgeous, gorgeous wildflowers, and people were flocking there to see them. And when I did some reading about this, I found that this was caused by, the region had had its worst dry spell in history. And then it was followed by twice the normal wintertime precipitation. And that led to this really beautiful event. And so I was thinking about that, as I was writing this poem about the ways that sometimes destruction can look like beauty, can be beauty in a way.

The 2017 southern California super bloom, seen here at Walker Canyon, inspired Pierce’s poem “Anthropocene Pastoral.” (Photo: Beau Rogers, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

This is called Anthropocene Pastoral.

In the beginning, the ending was beautiful.

Early spring everywhere, the trees furred

pink and white, lawns the sharp green

that meant new. The sky so blue it looked

manufactured. Robins. We’d heard

the cherry blossoms wouldn’t blossom

this year, but what was one epic blooming

when even the desert was an explosion

of verbena? When bobcats slinked through

primroses. When coyotes slept deep in orange

poppies. One New Year’s Day we woke

to daffodils, wisteria, onion grass wafting

through the open windows. Near the end,

we were eyeletted. We were cottoned.

We were sundressed and barefoot. At least

it’s starting gentle, we said. An absurd comfort,

we knew, a placebo. But we were built like that.

Built to say at least. Built to reach for the heat

of skin on skin even when we were already hot,

built to love the purpling desert in the twilight,

built to marvel over the pink bursting dogwoods,

to hold tight to every pleasure even as we

rocked together toward the graying, even as

we held each other, warmth to warmth,

and said sorry, I’m sorry, I’m so sorry while petals

sifted softly to the ground all around us.

Catherine Pierce is the author of four books of poems including Danger Days and The Tornado Is the World and is professor of English and co-director of the creative writing program at Mississippi State University. (Photo: Megan Bean / Mississippi State University)

CURWOOD: Catherine, it sounds like you're in a way seeking permission to find beauty in, in what can happen during climate disruption, to, quote, "hold tight to every pleasure." How do you think allowing ourselves to see this beauty in the midst of this emerging disaster is vital for our emotional resilience?

PIERCE: I think it's crucial for two reasons. One is, I mean, as you say, it's, it's vital for our emotional resilience. If we're not able to take joy and pleasure in these moments as we find them, how can we possibly be strong enough to do what we need to do? Which is, which is the other part of why it's necessary, we need to be able to recognize this beauty so that we can try to save it. Right, we need to feel spurred to action by our relationship with this planet and with everything that it offers us. We need art, we need beauty, we need poems and walks in the woods and songs and essays, we need all these things, to allow us to feel the true pleasure that comes from paying attention to this world, which is just an absolutely remarkable place. But then we also need to feel strengthened by that into taking action, into trying to keep this amazing planet as something that our kids can explore with the same pleasure that we could, and that their kids hopefully can explore with the same kind of pleasure as well.

CURWOOD: Catherine Pierce is the author of Danger Days, The Tornado Is the World and other books of poems. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

PIERCE: Thank you so much for talking with me.

Related links:

- Catherine Pierce’s poetry and more

- Purchase Danger Days by Katherine Pierce from bookshop.org to support both Living on Earth and local independent bookstores

[MUSIC: The Mount Vernon Virtuosi Cello Gang/Amit Peled, Medley: “Hallelujah/What a Wonderful World” on Around the World in Five Cellos, by Leonard Cohen/ Bob Thiele and George David Weissin, live at Baltimore’s Creative Alliance]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Paloma Beltran, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Karen Elterman, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mattie Hibbs, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Sarah Mahaney, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments@loe.org. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth