Why Fish Don’t Exist

Air Date: Week of August 2, 2024

“Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life” is Lulu Miller’s first book. (Image: Courtesy of Simon & Schuster)

Fish scientist David Starr Jordan discovered thousands of new fish species around 1900, and kept going even as he faced repeated disasters that threatened to obliterate his life’s work. His stubborn optimism is the springboard for science journalist Lulu Miller’s new book, “Why Fish Don’t Exist”, and the search for order in a cold, chaotic world. Lulu Miller and Host Steve Curwood discuss what her journey into science and the past uncovered about the astonishing life of David Starr Jordan.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

You might recognize the voice of our next guest from your radio or podcast app. Lulu Miller is the co-host of Radiolab and co-founder of Invisibilia.

But she’s also the talented author of the 2020 book “Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life". Lulu uncovers the story of a scientist named David Starr Jordan, who discovered and named thousands of new aquatic species even as disaster after disaster threatened to obliterate his life’s work. Lulu Miller joins me now from Chicago. Welcome!

MILLER: Thank you so much for having me. I've been a huge fan of the show for years, and it's a real treat to be with you.

CURWOOD: Lulu, let's start where you started on this book project. What about David Starr Jordan, this obscure ichthyologist, fish scientist, caught your eye and why?

MILLER: Yeah, why! You know, I didn't even know his name at first. I had just heard this one detail about somebody, the person in charge of a fish collection in San Francisco, that was destroyed after the 1906 earthquake. Hundreds of fish fell, the jars were shattered, they were separated from their names. And I had just heard this detail that after the earthquake, instead of just kind of giving up and being overwhelmed, this man innovated and he started this new way of attaching labels to the fish. He sewed them on with a sewing needle as this kind of hope that chaos would never get him again. And it was this really tiny detail that for some reason just kind of made me chuckle and made me think, Oh, he's such a good emblem for the human spirit, like our refusal to back down even when, when the world completely destroys our mission. And I just slowly began to wonder about him. I began to wonder, hey, did his trick work? Did chaos get him later? What, what becomes of someone so confident in the face of chaos itself?

CURWOOD: Of course, he was a collector of all those fish. Part of your book explores collecting as a passion. What is it about collecting as a passion?

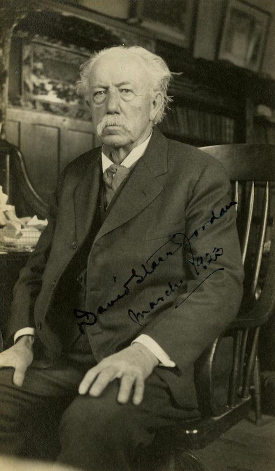

David Starr Jordan in 1908. (Photo: F. Davey, Public Domain)

MILLER: I just think there's something so human about it, and so odd when you zoom out, like, I think that was one of the things that drew me in. What is this desire to preserve and order, to fussily arrange everything? For him, it's natural objects, it's fish. And so he's trying to understand the shape of the great tree of life and how everything is connected evolutionarily to one another. But we all do this in certain ways. You know, as a documentarian, I'm walking around with a microphone all the time collecting moments, and it's like a tick, I can't stop. And I think there's part of me that wonders where that desperation comes from in people. And so I think in certain ways, I, it was a very different form: collecting fish, versus collecting moments and memories, but I think I really identified with him. And I kind of wondered, what becomes of you when you don't even let yourself get a handle on it, like, he just gave into it and he was just so obsessive.

CURWOOD: Your own writing suggests that maybe collecting is a way to deal with chaos.

MILLER: Absolutely. Yes, I think it is one of the few ways; you might not be able to stop the lightning or the earthquake or the virus; you know, you might not be able to stop it. But if you can collect little bits of information, little bits of the world; if you can know them, if you can name them, with more and more accuracy, you might have better ability, I think, to protect yourself from the chaos, or at least have the illusion of control. There's a psychologist, Werner Muensterberger, I write about who studied obsessive collectors for decades. And he wrote that oftentimes people's collecting became sort of pathological and obsessive after some huge deprivation or tragedy, and that with each new acquisition, there was this temporary burst of, he called it, "fantasized omnipotence". Like, this little hit, that you have control, in a world where we know we don't.

CURWOOD: Who was this guy, really, this fish scientist David Starr Jordan?

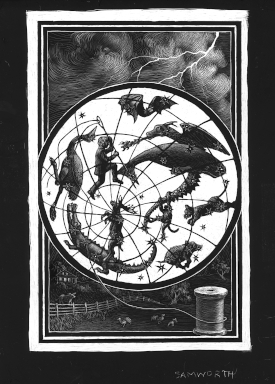

The artwork for the book’s prologue. (Illustration by Kate Samworth)

MILLER: Yeah, so he was, he was an American. He was born in upstate New York, and he was born in 1851. And always loved nature. And as a little kid, he was kind of mocked for his love of nature. And the way he studied the world, by literally crawling around in the dirt and looking at it, was actually starting to fall out of fashion sort of temporarily in academia, where people were putting more weight on books and recitation of beliefs. And so he couldn't get a job. His first job was a teaching job and his students grabbed the pointer out of his hand and set it on fire. Like, he couldn't get a girl; I mean, he was just, he was as a younger kid, he was beat up. I mean, he was just your classic, nature loving, sweet nerd, and the world would not cut him a break. So that sort of made me fall in love with him, because he just stayed dedicated; you know, the first thing he wanted to do was name the stars. And then he believes that he learned the name of every star, and then he moved on to flowers. And then finally he moved on to fish. And so he's in his early 20s, when he meets a teacher who really changes his life and that's Louis Agassiz, the famous Swiss naturalist who told him, "Study nature, not books". And when he starts studying under the tutelage of Agassiz, his life changes. He suddenly kind of gains this sense of purpose in what he's doing. He gets a great job at Indiana University. He becomes the president of Indiana University. Then he becomes the first president of Stanford. You know, he gets a wife and kids and he starts commissioning with the Stanfords' money, all these expeditions all over the world to collect fish. And as the years go on, he and his team just start discovering hundreds of new species. And I think about like, in a scientist's life, I think to discover one species is, is huge. And to discover over 2,000, at that point, it was like a fifth of fish known to man in his day, so he really helped uncover a massive amount of the tree of life. Like, I think of this whole scaly, lower branches, like a big section of it.

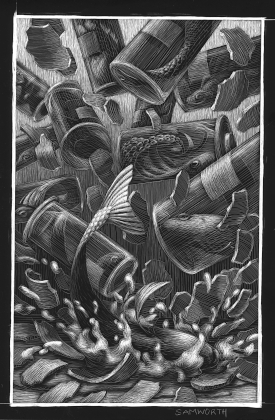

The only fish David Starr Jordan chose to name after himself is the Agonomalus Jordani, a kind of MC Escher of a fish, according to Lulu Miller. (Illustration by Kate Samworth)

CURWOOD: So to what extent was this a nice guy?

MILLER: In certain ways, he's full of charm. And from a young age, he says he dedicated his life to the, quote, "hidden and insignificant". He believed that the best clues to nature's plan lied in the unknown, that the true scientists notices everything, and the small. You see that in his life and you see this just profound curiosity. And he's really charming; his, one of the things that made him so great to study is he's really funny, like, he's a funny writer. And he has these odd little goals, like he wants to be able to clasp his hands and jump through them as a little boy, which you just picture. And he, he writes these hilarious satires about people who believe in the occult, and you know, he's kind of mean, but he's really funny. And he does a lot of good. He was really passionate about coeducation, about women getting equal education at Stanford. He was he was a pacifist, he was opposed to World War I at a time that was really unpopular and spoke out against it.

CURWOOD: But?...

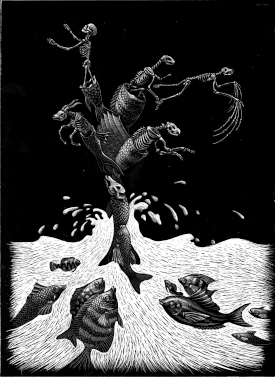

An illustration from the book capturing the moment of destruction during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, when David Starr Jordan’s entire collection shattered on the floor of the Stanford Zoology building. (Illustration by Kate Samworth)

MILLER: [LAUGHS] But, there was, um . . . if you got in the way of his goals, he was an utter bulldozer. I mean, he got people fired. There is a lot of evidence that suggests he was involved in a murder; if not in the murder, he was definitely involved in a cover up of a murder. And then the latter third of his life, he was a passionate eugenicist and just could not hear any of the opposition, you know, whether it was the Catholic Church or other scientists calling his ideas, quote, "rot", or judges calling eugenics "an engine of tyranny and oppression". I mean, there was opposition, and he just didn't hear it. Even victims of sterilization themselves saying, quote, "I'm a human being just like you". He just dedicated himself further and further to the cause, and in so doing harmed thousands of lives. So, he's got . . .

CURWOOD: Hmm, well, and being a scientific descendant of Louis Agassiz, who, you know, saw a biological basis for race and all that, that makes a lot of sense.

MILLER: Yes. Yeah.

CURWOOD: One of the things that you point out, you know, of the thousands of species, you said like 2,000 species that he and his team identified, he named one after himself. And you actually went to the Smithsonian to see the specimen. Describe it for me, please.

To add insult to injury, not only did the 1906 earthquake virtually obliterate David Starr Jordan’s precious fish specimen collection, it also toppled the statue of his beloved mentor, the naturalist Louis Agassiz, that had stood just outside the Stanford Zoology building. Lulu Miller observes, “If I were the director of this particular play, I’d tell the set designers to dial it back a notch.” (Photo: Mendenhall, Stanford University, Wikimedia Commons)

MILLER: Ah! Okay. It's a kind of poacher fish called the Agonomalus Jordani. It looks like a dragon, looks like a tiny dragon with big wings, sort of serrated wings. And it almost, its body almost looks like a curling staircase, a spiral staircase. To me it almost looks like an MC Escher drawing where like there are so many corners and curves, but nothing quite lines up. And there's just something a little unsettling about it. It also is really spiny. And so I went to see it, the one; it's called the holotype, which is the very first specimen of a species, so the first physical creature that was ever named; this kind of holy object. And they, they took it; the scientist, she took it with metal tongs out of the jar, and then she placed it in my hand! And I got to hold it with my bare hand. And they're, they're known for being these kind of violent hunters; they'll camouflage themselves with muck and then they'll use those wing-like things, which are fins obviously to, to just strike at incredible speed and get their prey, little crustaceans, before they know what hit them. And so, he discovered so many beautiful, rainbow-colored; crimson; things that glow. And I just I wondered, huh, that was the one in the entire sea, the only one he chose to grace with his name, and I wondered why? I mean, did he see something of himself in that? Did he admire that? Why was that the one.

CURWOOD: That he loved a fish that one might call a monster.

MILLER: Yeah. As a boy, he was always drawing, one of my favorite parts of his archives is it is filled with drawings and doodles, like scientific drawings of flowers, beautiful with ink, and he's not great at it but he's dedicated. They're, they're just, everything's filled in, every single petal, hundreds of them. And then in his later life, he just started drawing beasts, hundreds of them. These, these fantastical beasts that he was making up. He was definitely increasingly obsessed with monsters, I think that that is fair to say.

David Starr Jordan in 1923, at age 72. (Photo: Unknown Author, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Well, I'll leave it to the reader to consider the monster within that you wonder about. Of course, David Starr Jordan, as you write, faced personal disaster after personal disaster. I mean, what's the list? First he loses his big brother in the Civil War to disease, the way most soldiers died in the Civil War, by the way. And then you talked about his collection getting smashed during the earthquake, and . . .

MILLER: And before that, the first collection he built was struck by lightning and burned to the ground. Like, just another detail in his life that doesn't faze him! His first wife died very young after they had had three kids. Then following her death, their baby died. His very first collection you could argue of maps was destroyed by the chaotic force of his own mom. She took all his maps, she thought that what he was doing was a waste of time. She was this Puritan and she chucked 'em. He recruited his one of his best friends from college to come help him on the quest of, he wanted to discover every freshwater fish of North America. And less than a year into their quest, his colleague fell overboard and froze to death while they were searching for fish. I mean, just all around him -- two of his favorite students that he trained in the art of relentlessly pursuing the unknown died while collecting. It felt like his life was plagued by destruction in a fairly uncanny way.

CURWOOD: Now, one of the things you write is that David Starr Jordan had this unflappable optimism about ordering the world, persisting even as all these disasters happen. And he did some pretty horrible things along the way. You know, you raise the questions, ooh, was he involved in a murder? Oh, was, he spent a lot of time with eugenics. So I take it by the end of your book, you're pretty disgusted with David Starr Jordan. [LAUGHS] And you are delighted when you come across a kind of cosmic justice for him. What happened?

“Fish do not exist” because as scientists began to realize in the 1980s, the category of “fish” is evolutionarily nonsensical. (Illustration by Kate Samworth)

MILLER: Yeah. So in a certain way it looked like he went to the grave unpunished for his sins and his bad behavior. But then posthumously, there was this incredible discovery, basically, in the 1980s, that fish -- the group, the category of fish -- does not exist. It is not a valid grouping of creatures. So you could say -- it's a category you could make. So you could say, you know, if you wanted to make a group of all creatures that have stripes, fine, that's a group you can call it the stripies. Similarly, fish, you could say all finny things that you know, swim underwater, but aren't whales, aren't mammals. You know, you could say that's a group and you could call it fish. But if you want to actually look at how creatures are related evolutionarily, fish is a totally bunk category. There are creatures such as the lungfish or the coelacanth, which are far more closely related to us, for example, than to their near twin, it looks like, you know, from the outside, a salmon or something.

CURWOOD: And by the way, for those who aren't so acquainted with the Linnean way of classifying, you know, amphibians are a class, mammals are a class. Some would say birds are a class. But fish are not?

_Kristen_Finn.jpg)

“Why Fish Don’t Exist” author Lulu Miller is also a cofounder of NPR’s “Invisibilia”. (Photo: Kristen Finn)

MILLER: Correct. And to me, there's something so poignant about, you know, the universe first strikes with lightning and then with an earthquake and it keeps trying to steal its fish back. Or, you know, this is one way to read his tale. And he keeps trying to overcome it. And then right at the end, the way the universe finally steals his fish is, in a way is by his very own hand, by his own obsession, by his own desire to order creatures. If you were to follow that to its current end, you would see that fish was never, was never an actual grouping at all.

CURWOOD: Lulu, so then how did you come to process this idea that fish don't exist? And, and what does that mean for your life?

MILLER: The best way I can explain it, what I've slowly come to understand is what these scientists are saying is that fish is a gerrymandered category. It's a term we use, it's a proxy that we use to parse the chaos. But it is a way that we keep our sense of superiority intact. And if you want to look more closely at nature, having an openness to the sense that most of our intuitive categories might actually be wrong, can help you see the world more expansively. And so I think, for me, this, this wacky concept that fish does not exist. It's become a mantra in my mind and a reminder, to think about what other categories and hierarchies we may be believing in that we need to re examine.

CURWOOD: Lulu Miller is a cofounder of NPR's Invisibilia and the author of Why Fish Don't Exist. Lulu, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MILLER: Thank you so much, Steve.

Links

Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth