August 2, 2024

Air Date: August 2, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean

View the page for this story

The oceans cover 70 percent of our “blue planet” yet remain largely unexplored because of the intense pressures at depth. But there are some intrepid few who have descended into this “underworld” and lived to tell of its marvels. (14:41)

Why Fish Don’t Exist

View the page for this story

Fish scientist David Starr Jordan discovered thousands of new fish species around 1900, and kept going even as he faced repeated disasters that threatened to obliterate his life’s work. His stubborn optimism is the springboard for science journalist Lulu Miller’s new book, “Why Fish Don’t Exist”, and the search for order in a cold, chaotic world. Lulu Miller and Host Steve Curwood discuss what her journey into science and the past uncovered about the astonishing life of David Starr Jordan. (15:38)

Farewell to Peter Dykstra

View the page for this story

Living on Earth host Steve Curwood announces the death of our beloved correspondent Peter Dykstra. We are preparing a tribute, and invite listeners to write in with your own fond memories. (00:38)

“Earth, Sometimes I Try to Play It Casual”

View the page for this story

Poet Catherine Pierce reads her poem, “Earth, Sometimes I Try to Play It Casual” about the meaning of “celebrating the Earth” by being present to the wonders around us. (01:33)

Ross Gay's Book of (More) Delights

View the page for this story

Poet and essayist Ross Gay is back with a follow up to his 2019 Book of Delights, loaded with moments of good that sprout amid our troubles. He joins Host Steve Curwood to share readings from his new Book of (More) Delights celebrating simple joys such as clothes on a clothesline, garlic sprouting, and dandelion abundance. (14:58)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

240802 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Susan Casey, Lulu Miller, Catherine Pierce, Ross Gay

CURWOOD: From PRX this is Living on Earth

(THEME)

I’m Steve Curwood

What it’s like to dive miles beneath the surface of the ocean.

CASEY: To go into the underworld, it’s the hero’s journey. It’s, you’re going down there and it’s not an easy journey. At the bottom of the Mariana Trench, for example, you’re going to have 16,000 pounds of pressure per square inch. So there are rules that you have to adhere to, to be able to make this journey.

CURWOOD: Also, more delights from poet Ross Gay.

GAY: It is truly overnight sometimes it seems that the dandelions put on their crowns, and just like that, the world is suddenly brighter, more abundant, more possible— this, of course, if you, like me, adore the dandelion, see their un-martialed ranks suddenly outflanking the gloom, outflowering the doom.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth—stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean

The Underworld: Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean is Susan Casey’s latest book. (Image: Courtesy of Susan Casey)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Summer’s not over yet so we’re sharing some of our favorite author interviews in case you’re inspired to tuck another book in your beach bag.

And this first one features wonders you’ll only find offshore. Seen from space, ours is a blue planet thanks to the oceans that cover some 70 percent of its surface. Yet despite their dominance we really know very little about them. Our soft human bodies just aren’t designed to withstand the intense pressures of the deep oceans, let alone the lack of air for lungs to breathe. But there are some intrepid few who have descended into this vast and seemingly forbidden underworld and lived to tell of its marvels. Journalist Susan Casey is among them, and in her book, The Underworld: Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean, she illuminates the immense world miles beneath the surface and the people committed to exploring it, and she joins me now. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Susan!

CASEY: Thanks, Steve.

CURWOOD: So when you step into the formal text of your book, you start talking about the history of the ocean and how humans thought of it as filled with monsters hundreds of years ago, their drawings are some famous ones. There are myths that Atlantis is down there. This is supposed to be a fairly spooky place. Of course, nowadays, we know better. But I have to say some of the photos in your books of some of the deep-sea creatures, well, maybe they are kind of monstrous. How do you think about both how far we have come in understanding the ocean and the mysteries that remain?

The Limiting Factor landing on the seafloor of the Mariana Trench’s Challenger Deep, the ocean’s deepest spot (35,876 feet). (Photo: Courtesy of Susan Casey)

CASEY: Well, it's really exciting to me that basically, we're the first generations of people that will actually be able to know, what are these creatures, what is down there. Technology is helping us, but it wasn't all that long ago, only about 150 years, that nobody knew at all what the bottom of the ocean looked like, what it was made of, you know, what lived down there, did anything live down there? So there were, preceding that, a lot of superstitions and myths and lack of knowledge, which led to confusion, I think. And one of the things I say in the book is, imagine you're a medieval farmer, and you're walking along the shore in Scandinavia sometime during the 16th century. And you come across the stranded, beached body of a sperm whale, like what are you thinking that is? You don't really know. But it looks pretty monstrous. And we've been told, throughout sort of the deep history, that, you know, there were monsters in the Bible, there was Leviathan, there were monsters in Greek myths. They lived underwater in this hidden underworld that we weren't privy to. And the thing is, they really aren't monstrous, but they're very different from us. They have a very different set of evolutionary needs. They've adapted to incredible pressures. They've adapted to living full time in the darkness. And this is not something that we relate to, life that really doesn't look like us. It may not even obey the same basic laws of life that we do, that, you know, say we thrive on photosynthesis. There are creatures at the bottom of the ocean that will never see the sun. And so their lifeforce is basically coming from the internal heat and minerals and gases and microbes from the planet in a process known as chemosynthesis. We only discovered this in 1977. So life had this entirely different trick up its sleeve that we didn't even know about. And we're still finding out all sorts of things. But I do think it's the otherness, sometimes, that makes people think ‘monster.’ But a lot of the times when you see these creatures, I mean, I tend to think of them as just adorable. A lot of the times they're quite small, the fish with the really big teeth and the big eyes, that's what you get when you adapt to living in the darkness 100% of the time, and food doesn't come along very often, and when you catch it, you have to have jail bars on the front of your mouth to make sure it doesn't get away.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, you point out in your book that yeah, maybe they don't have the visual acuity all the way down, but they use sound in intricate and exquisite ways.

The elongated bristlemouth, a tiny, glittery predator that is likely the most abundant vertebrate on earth. Trillions of these fish live in the uppermost layer of the deep ocean, known as the twilight zone (from 200–1,000 meters). More creatures live in the twilight zone than in all the other regions of the ocean combined. (Photo: Paul Caiger, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

CASEY: Oh, absolutely. I mean, sound travels far and fast in the ocean, more so than it does in air. And when you think about it, you know, we're primarily visual creatures. But that's not the greatest sense on a planet that's 95% in darkness 100% of the time. So there are other means in the ocean of communicating, and sound is one of them. There's also bioluminescence, which is the ability to create light. Not very many creatures have this on land. But in the ocean, it's a major part of the arsenal of tools that they have to be able to hunt, to mate, to get away from danger, to do all sorts of things. So when you go down in a submersible, you see these bursts of light, like fireworks kind of all around you. Because 80% of the animals in the uppermost parts of the deep ocean can illuminate themselves.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the layers of the deep ocean. I mean, I've gotten to go, I don't know, maybe 70 or 80 feet down. And you know, with a tank strapped to my back at one point, there's a lot more ocean there. And you in fact, were able to go on a few deep-sea dives. What was that like? And talk to me about the layers that you went through.

A Sloan’s viperfish, also found in the twilight zone. Eighty percent of the twilight zone’s creatures use bioluminescence for hunting, mating, hiding, and other purposes. Deep-sea fishes like this one look fearsome, but most are quite small. (Photo: Paul Caiger, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

CASEY: When people think of the ocean, they typically think of the very uppermost layer, which is the sunlight or photic zone, where there's light through the water. And even at the deepest you can scuba dive, you're still seeing sunlight, at least there is sunlight in the water. But below that is the uppermost layer of the deep ocean, and that's the twilight zone or the mesopelagic zone. And that goes from 200 meters, so about 600 feet, down to 1000 meters, so about 3300 feet. And then below that you have another vast midwater area called the midnight zone that goes from 1000 meters to 3000 meters. Below that you have the abyssal zone, or the abyss, which goes - it's the largest ecosystem on Earth, and it's 3000 meters to 6000 meters. And then below that, in certain parts of the ocean, there's the deepest part. It's where the tectonic plates collide and one plate is being subducted beneath another, and that's from 6000 meters almost down to 11,000 meters in the deepest spot in the ocean. That's called the hadal zone. And those deep areas are called hadal trenches, where these tectonic plates are colliding. The Mariana Trench is one that people tend to know. But there are dozens of others. So the deepest spot that we know of is called the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, and that's 35,867 feet by our latest calculations. It's actually very hard to get an exact depth calculation. And I went as far down as the abyssal zone. I went about 17,000 feet, about 5200 meters. I also went through the twilight zone, which is really amazing, because I call it the Manhattan of the deep, because there are more creatures living in the twilight zone than in all the other regions of the ocean combined. So it's a really active place and very scenic because all these creatures are illuminating themselves and flashing and blinking and wafting in front of you and sparkling.

A Triton three-person submersible with a transparent pressure sphere at 3,300 feet in the Bahamas. Transparent pressure spheres offer passengers a kaleidoscopic view of the deep, but they can’t be used below 6,000 feet. At greater depths, a titanium or steel pressure sphere is required because of the immense pressures. (Photo: Courtesy of Susan Casey)

The abyss is... it took us two and a half hours of free falling to get down into that realm and get the sense that the deeper you go, the more profound it feels. You're definitely aware of the weight, the pressure. I mean, that's 500 atmospheres on your head. There's a gravitas to it. But there's also a serenity, a real serenity, you realize that it is not space, because it's alive. I never forgot where I was. But I was in such awe of where I was that the time goes very elastic, like you could be down there for an hour and you would think you were down there for 15 minutes. There's no signposts. There's none of the things that we tend to look for above, you know, that give us a sense of our surroundings. It's all fluid. It's a spectacular experience that really changes your perspective of your place on Earth. This vast, vast, vast region that we never even think of - it is the vast majority of the Earth. So it's amazing to meet it.

CURWOOD: It's interesting the nomenclature, though, we use culturally. All the way at the bottom, the Hades zone. Hades, the god of the underworld. Your book, in fact, is called The Underworld. And in a colloquial way, we are thinking of, you know, crime, the wrong side of life when we talk about the underworld. Why did you pick this title? Why did you pick this name? And why do people who look at the oceans use such names to describe what's there?

Leptothecata jellyfish are one of the many creatures living in the twilight zone. (Photo: Paul Caiger, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

CASEY: Well, I think we have it baked into our language, you know, enlightenment, you're being raised up. And anything that takes us upward toward the light, like, up is good, down as bad. And we're kind of scared of bad, you know, it's dark, and we don't know what's there and we can't breathe. But to go into the underworld in Greek mythology is, it's the hero's journey. It's, you’re going down there, and it's not an easy journey. It takes humility, actually, it's the opposite of conquest. When we go into the deep ocean, we're using the best technology that we have, the best engineering that we, we have, and we know exactly what kind of forces we're going to be meeting. At the bottom of the Mariana Trench, for example, it's, you're gonna have 16,000 pounds of pressure per square inch. So there are rules that you have to adhere to, to be able to make this journey and come back home. And we're not necessarily the best at that. We're good at, you know, we love to the idea of blasting our rockets into space, and maybe we'll get a Mars colony, and maybe we'll expand our reach. But the inward journey, the journey into darkness, it's a different kind of journey. And the underworld in other cultures, it - that's where they kept the treasure. And I mean, I think that's one of my major theses in this book, is that this is a realm that is magical beyond measure, fascinating beyond measure. And we've neglected it, even though it really behooves us to understand more about it, because we're a little bit scared of it. And some people are a lot scared of it. But it is where the treasure is.

A species of cusk eels known as robust assfish, found in the waters as deep as 27,000 feet. These assfish live in the ocean’s deepest realm, known as the hadal zone (named after Hades, the underworld). (Photo: Alan Jamieson and Thomas Linley)

CURWOOD: So your book describes a series of some kind of amazing characters, people who, in fact, decide to go down there. Talk to me about some of those people and their love of this underworld.

CASEY: When I report my books, I try to embed myself with people that are sort of doing the most extreme things in the environment that I want to write about and doing them well, so that there's a sense of being on the cutting edge as I'm following them through, say, in this book, it was embedding with the Five Deeps Expedition, which took place in 2019, and it was sort of the debut of the first full ocean depth manned submersible, which was owned by an individual named Victor Vescovo, businessman from Texas, who's also a very committed adventurer. And by the time I met up with him, Victor had already been to the top of the tallest peaks on every continent and skied to the north and south poles, and had looked around and thought, "Okay, what else can I do?" and was kind of shocked to find out that we hadn't been to the bottom of the hadal trenches, for the most part. And only three people in history had been to the bottom of the Challenger Deep, which is the deepest spot in the Mariana Trench. And in the time that it had taken three of us to get down there, you know, like 200 people had been to the International Space Station and thousands of people had been to the top of Mount Everest. So he thought, "Well, wait a minute, let's do that." I tend to like very obsessive, very colorful characters, and he is certainly one. He commissioned, I think the best submersible company in the world, this company Triton Submarines based in Florida (I call them the Apple of submarine design) to create a two-person sub that could repeatedly go safely to the bottom of the deepest spots in the ocean every day of the week. And we had never had such a vehicle. It was not necessarily agreed upon that it was even possible because of the pressures to do this. And so Five Deeps was this sort of historical expedition that I was fortunate enough to be able to embed myself with. You know, in nonfiction, I make room for luck. And this was really a stroke of luck, timing wise, because I think in the history of deep-sea exploration in the future, will be divided before this submersible and after this submersible. It really opened up the hadal zone. And along with taking me down there, Victor also took a whole lot of hadal scientists who had been studying this realm, and it's not easy to study the deepest parts of the ocean, but they had never seen it. So he took them down in person. It just changed everything, this submersible, so I really wanted to share all kinds of details of that with readers.

These hadal snailfish, photographed in the Mariana Trench, are the world’s deepest fish. They’ve been found as deep as 29,300 feet and have adapted to the hadal zone’s crushing pressures. Hadal snailfish have no swim bladders or other air cavities in their bodies; their innards are encased in a buoyant, transparent gel. (Photo: Alan Jamieson)

CURWOOD: You have the curiosity for what's down there, then you get to go. What did you discover?

CASEY: I love the question because you discover things about yourself. You discover this perspective, our place on Earth, like I really am a fan of this humility in the face of nature that's bigger than we are, so much bigger than we are. And I think it's very hard for people to wrap their heads around how vast the deep ocean is. Everything we know, we see on land, is 2% of Earth's biosphere. The deep ocean is 95. So you get the sense of yourself as exquisite, but insignificant piece of the cosmos. You know, we're just here as part of it. And I love that. I love that feeling of humility, of being part of nature and being able to sort of revel in it. I think we lose sight of the fact that we are part of nature, and we think our job is to run it and own it, and, you know, use it. That's a delusion, and the ocean will set you very straight about this very fast.

CURWOOD: So, Susan, before you go, what do you hope for the future of underworld exploration?

Susan Casey, the author of The Underworld, entered the hatch of Victor Vescovo’s full ocean depth sub, the Limiting Factor. (Photo: Joe MacInnis, Courtesy of Susan Casey)

CASEY: You know, if you're not claustrophobic, I think going deep, like going below 600 feet if the possibility arises, and I think there will be more opportunities in the future to do this safely, it really is something that I think everybody would revel in, except for possibly claustrophobic people. But I just think that it is, the ocean is the greatest teacher, and the deep ocean in particular, for the sense of humility. I think it's a superpower. And I wish we could avail ourselves of it more above the surface, because I think that we would have a smoother ride. If we realize that this is all this massively interconnected, intricate system, and we're just beginning to understand that, and we should move with respect and caution. And at the same time, just delight in the beauty of it. Because everybody thinks they know that the deep ocean is spooky and scary, but I don't think people realize at all how beautiful it is.

CURWOOD: Susan Casey's book is called The Underworld: Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

CASEY: It's my pleasure.

Related links:

- Explore more of Susan Casey’s work.

- Learn more about the Five Deeps Expedition

- Differentiate the ocean’s zones.

- Purchase The Underworld and support both local bookstores and Living on Earth.

Abel Korzeniowski, “Dance For Me Wallis” on W.E.-Music From The Motion Picture, Interscope Records.

CURWOOD: Coming up, Lulu Miller on, Why Fish Don’t Exist. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org.

Jacob Christoffersen Trio, “We Want You” on Stunt Records 2017, by J. Christoffersen, Sundance Music

Why Fish Don’t Exist

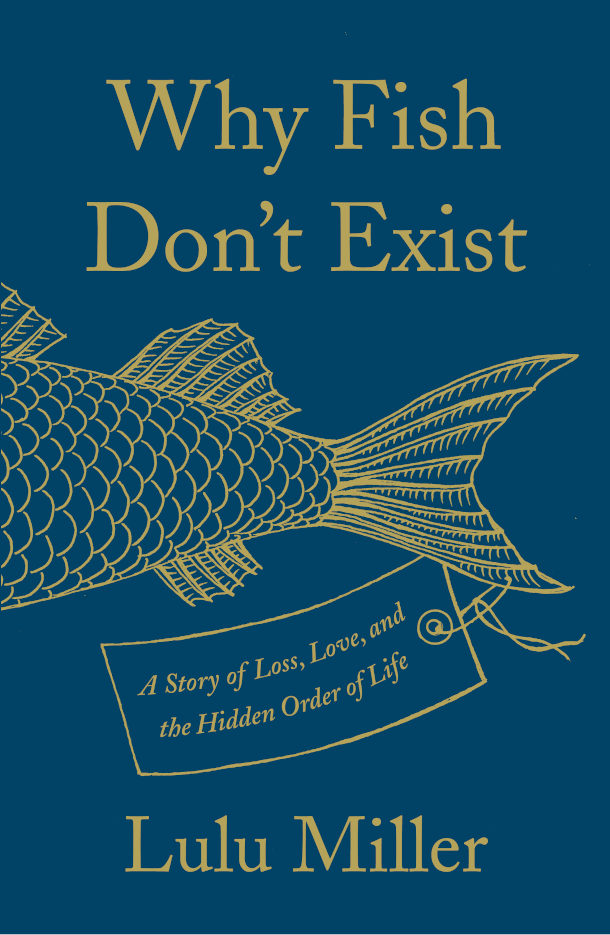

“Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life” is Lulu Miller’s first book. (Image: Courtesy of Simon & Schuster)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

You might recognize the voice of our next guest from your radio or podcast app. Lulu Miller is the co-host of Radiolab and co-founder of Invisibilia.

But she’s also the talented author of the 2020 book “Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life". Lulu uncovers the story of a scientist named David Starr Jordan, who discovered and named thousands of new aquatic species even as disaster after disaster threatened to obliterate his life’s work. Lulu Miller joins me now from Chicago. Welcome!

MILLER: Thank you so much for having me. I've been a huge fan of the show for years, and it's a real treat to be with you.

CURWOOD: Lulu, let's start where you started on this book project. What about David Starr Jordan, this obscure ichthyologist, fish scientist, caught your eye and why?

MILLER: Yeah, why! You know, I didn't even know his name at first. I had just heard this one detail about somebody, the person in charge of a fish collection in San Francisco, that was destroyed after the 1906 earthquake. Hundreds of fish fell, the jars were shattered, they were separated from their names. And I had just heard this detail that after the earthquake, instead of just kind of giving up and being overwhelmed, this man innovated and he started this new way of attaching labels to the fish. He sewed them on with a sewing needle as this kind of hope that chaos would never get him again. And it was this really tiny detail that for some reason just kind of made me chuckle and made me think, Oh, he's such a good emblem for the human spirit, like our refusal to back down even when, when the world completely destroys our mission. And I just slowly began to wonder about him. I began to wonder, hey, did his trick work? Did chaos get him later? What, what becomes of someone so confident in the face of chaos itself?

CURWOOD: Of course, he was a collector of all those fish. Part of your book explores collecting as a passion. What is it about collecting as a passion?

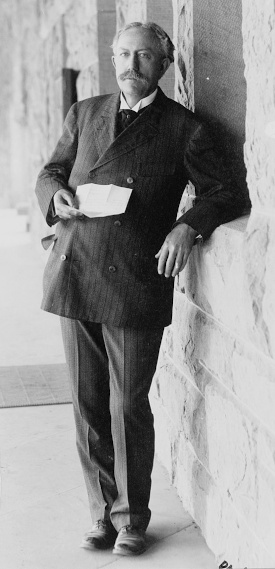

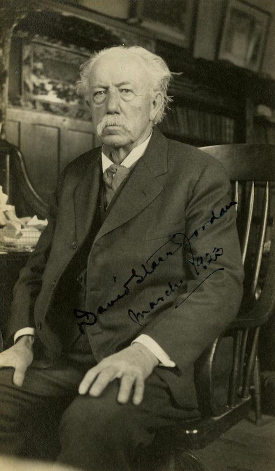

David Starr Jordan in 1908. (Photo: F. Davey, Public Domain)

MILLER: I just think there's something so human about it, and so odd when you zoom out, like, I think that was one of the things that drew me in. What is this desire to preserve and order, to fussily arrange everything? For him, it's natural objects, it's fish. And so he's trying to understand the shape of the great tree of life and how everything is connected evolutionarily to one another. But we all do this in certain ways. You know, as a documentarian, I'm walking around with a microphone all the time collecting moments, and it's like a tick, I can't stop. And I think there's part of me that wonders where that desperation comes from in people. And so I think in certain ways, I, it was a very different form: collecting fish, versus collecting moments and memories, but I think I really identified with him. And I kind of wondered, what becomes of you when you don't even let yourself get a handle on it, like, he just gave into it and he was just so obsessive.

CURWOOD: Your own writing suggests that maybe collecting is a way to deal with chaos.

MILLER: Absolutely. Yes, I think it is one of the few ways; you might not be able to stop the lightning or the earthquake or the virus; you know, you might not be able to stop it. But if you can collect little bits of information, little bits of the world; if you can know them, if you can name them, with more and more accuracy, you might have better ability, I think, to protect yourself from the chaos, or at least have the illusion of control. There's a psychologist, Werner Muensterberger, I write about who studied obsessive collectors for decades. And he wrote that oftentimes people's collecting became sort of pathological and obsessive after some huge deprivation or tragedy, and that with each new acquisition, there was this temporary burst of, he called it, "fantasized omnipotence". Like, this little hit, that you have control, in a world where we know we don't.

CURWOOD: Who was this guy, really, this fish scientist David Starr Jordan?

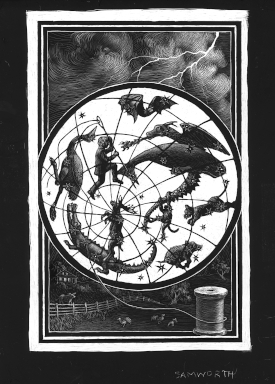

The artwork for the book’s prologue. (Illustration by Kate Samworth)

MILLER: Yeah, so he was, he was an American. He was born in upstate New York, and he was born in 1851. And always loved nature. And as a little kid, he was kind of mocked for his love of nature. And the way he studied the world, by literally crawling around in the dirt and looking at it, was actually starting to fall out of fashion sort of temporarily in academia, where people were putting more weight on books and recitation of beliefs. And so he couldn't get a job. His first job was a teaching job and his students grabbed the pointer out of his hand and set it on fire. Like, he couldn't get a girl; I mean, he was just, he was as a younger kid, he was beat up. I mean, he was just your classic, nature loving, sweet nerd, and the world would not cut him a break. So that sort of made me fall in love with him, because he just stayed dedicated; you know, the first thing he wanted to do was name the stars. And then he believes that he learned the name of every star, and then he moved on to flowers. And then finally he moved on to fish. And so he's in his early 20s, when he meets a teacher who really changes his life and that's Louis Agassiz, the famous Swiss naturalist who told him, "Study nature, not books". And when he starts studying under the tutelage of Agassiz, his life changes. He suddenly kind of gains this sense of purpose in what he's doing. He gets a great job at Indiana University. He becomes the president of Indiana University. Then he becomes the first president of Stanford. You know, he gets a wife and kids and he starts commissioning with the Stanfords' money, all these expeditions all over the world to collect fish. And as the years go on, he and his team just start discovering hundreds of new species. And I think about like, in a scientist's life, I think to discover one species is, is huge. And to discover over 2,000, at that point, it was like a fifth of fish known to man in his day, so he really helped uncover a massive amount of the tree of life. Like, I think of this whole scaly, lower branches, like a big section of it.

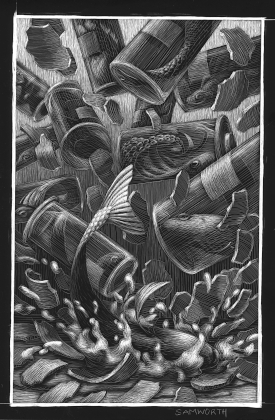

The only fish David Starr Jordan chose to name after himself is the Agonomalus Jordani, a kind of MC Escher of a fish, according to Lulu Miller. (Illustration by Kate Samworth)

CURWOOD: So to what extent was this a nice guy?

MILLER: In certain ways, he's full of charm. And from a young age, he says he dedicated his life to the, quote, "hidden and insignificant". He believed that the best clues to nature's plan lied in the unknown, that the true scientists notices everything, and the small. You see that in his life and you see this just profound curiosity. And he's really charming; his, one of the things that made him so great to study is he's really funny, like, he's a funny writer. And he has these odd little goals, like he wants to be able to clasp his hands and jump through them as a little boy, which you just picture. And he, he writes these hilarious satires about people who believe in the occult, and you know, he's kind of mean, but he's really funny. And he does a lot of good. He was really passionate about coeducation, about women getting equal education at Stanford. He was he was a pacifist, he was opposed to World War I at a time that was really unpopular and spoke out against it.

CURWOOD: But?...

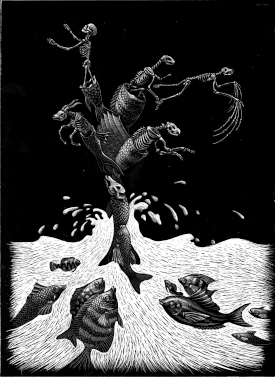

An illustration from the book capturing the moment of destruction during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, when David Starr Jordan’s entire collection shattered on the floor of the Stanford Zoology building. (Illustration by Kate Samworth)

MILLER: [LAUGHS] But, there was, um . . . if you got in the way of his goals, he was an utter bulldozer. I mean, he got people fired. There is a lot of evidence that suggests he was involved in a murder; if not in the murder, he was definitely involved in a cover up of a murder. And then the latter third of his life, he was a passionate eugenicist and just could not hear any of the opposition, you know, whether it was the Catholic Church or other scientists calling his ideas, quote, "rot", or judges calling eugenics "an engine of tyranny and oppression". I mean, there was opposition, and he just didn't hear it. Even victims of sterilization themselves saying, quote, "I'm a human being just like you". He just dedicated himself further and further to the cause, and in so doing harmed thousands of lives. So, he's got . . .

CURWOOD: Hmm, well, and being a scientific descendant of Louis Agassiz, who, you know, saw a biological basis for race and all that, that makes a lot of sense.

MILLER: Yes. Yeah.

CURWOOD: One of the things that you point out, you know, of the thousands of species, you said like 2,000 species that he and his team identified, he named one after himself. And you actually went to the Smithsonian to see the specimen. Describe it for me, please.

To add insult to injury, not only did the 1906 earthquake virtually obliterate David Starr Jordan’s precious fish specimen collection, it also toppled the statue of his beloved mentor, the naturalist Louis Agassiz, that had stood just outside the Stanford Zoology building. Lulu Miller observes, “If I were the director of this particular play, I’d tell the set designers to dial it back a notch.” (Photo: Mendenhall, Stanford University, Wikimedia Commons)

MILLER: Ah! Okay. It's a kind of poacher fish called the Agonomalus Jordani. It looks like a dragon, looks like a tiny dragon with big wings, sort of serrated wings. And it almost, its body almost looks like a curling staircase, a spiral staircase. To me it almost looks like an MC Escher drawing where like there are so many corners and curves, but nothing quite lines up. And there's just something a little unsettling about it. It also is really spiny. And so I went to see it, the one; it's called the holotype, which is the very first specimen of a species, so the first physical creature that was ever named; this kind of holy object. And they, they took it; the scientist, she took it with metal tongs out of the jar, and then she placed it in my hand! And I got to hold it with my bare hand. And they're, they're known for being these kind of violent hunters; they'll camouflage themselves with muck and then they'll use those wing-like things, which are fins obviously to, to just strike at incredible speed and get their prey, little crustaceans, before they know what hit them. And so, he discovered so many beautiful, rainbow-colored; crimson; things that glow. And I just I wondered, huh, that was the one in the entire sea, the only one he chose to grace with his name, and I wondered why? I mean, did he see something of himself in that? Did he admire that? Why was that the one.

CURWOOD: That he loved a fish that one might call a monster.

MILLER: Yeah. As a boy, he was always drawing, one of my favorite parts of his archives is it is filled with drawings and doodles, like scientific drawings of flowers, beautiful with ink, and he's not great at it but he's dedicated. They're, they're just, everything's filled in, every single petal, hundreds of them. And then in his later life, he just started drawing beasts, hundreds of them. These, these fantastical beasts that he was making up. He was definitely increasingly obsessed with monsters, I think that that is fair to say.

David Starr Jordan in 1923, at age 72. (Photo: Unknown Author, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Well, I'll leave it to the reader to consider the monster within that you wonder about. Of course, David Starr Jordan, as you write, faced personal disaster after personal disaster. I mean, what's the list? First he loses his big brother in the Civil War to disease, the way most soldiers died in the Civil War, by the way. And then you talked about his collection getting smashed during the earthquake, and . . .

MILLER: And before that, the first collection he built was struck by lightning and burned to the ground. Like, just another detail in his life that doesn't faze him! His first wife died very young after they had had three kids. Then following her death, their baby died. His very first collection you could argue of maps was destroyed by the chaotic force of his own mom. She took all his maps, she thought that what he was doing was a waste of time. She was this Puritan and she chucked 'em. He recruited his one of his best friends from college to come help him on the quest of, he wanted to discover every freshwater fish of North America. And less than a year into their quest, his colleague fell overboard and froze to death while they were searching for fish. I mean, just all around him -- two of his favorite students that he trained in the art of relentlessly pursuing the unknown died while collecting. It felt like his life was plagued by destruction in a fairly uncanny way.

CURWOOD: Now, one of the things you write is that David Starr Jordan had this unflappable optimism about ordering the world, persisting even as all these disasters happen. And he did some pretty horrible things along the way. You know, you raise the questions, ooh, was he involved in a murder? Oh, was, he spent a lot of time with eugenics. So I take it by the end of your book, you're pretty disgusted with David Starr Jordan. [LAUGHS] And you are delighted when you come across a kind of cosmic justice for him. What happened?

“Fish do not exist” because as scientists began to realize in the 1980s, the category of “fish” is evolutionarily nonsensical. (Illustration by Kate Samworth)

MILLER: Yeah. So in a certain way it looked like he went to the grave unpunished for his sins and his bad behavior. But then posthumously, there was this incredible discovery, basically, in the 1980s, that fish -- the group, the category of fish -- does not exist. It is not a valid grouping of creatures. So you could say -- it's a category you could make. So you could say, you know, if you wanted to make a group of all creatures that have stripes, fine, that's a group you can call it the stripies. Similarly, fish, you could say all finny things that you know, swim underwater, but aren't whales, aren't mammals. You know, you could say that's a group and you could call it fish. But if you want to actually look at how creatures are related evolutionarily, fish is a totally bunk category. There are creatures such as the lungfish or the coelacanth, which are far more closely related to us, for example, than to their near twin, it looks like, you know, from the outside, a salmon or something.

CURWOOD: And by the way, for those who aren't so acquainted with the Linnean way of classifying, you know, amphibians are a class, mammals are a class. Some would say birds are a class. But fish are not?

_Kristen_Finn.jpg)

“Why Fish Don’t Exist” author Lulu Miller is also a cofounder of NPR’s “Invisibilia”. (Photo: Kristen Finn)

MILLER: Correct. And to me, there's something so poignant about, you know, the universe first strikes with lightning and then with an earthquake and it keeps trying to steal its fish back. Or, you know, this is one way to read his tale. And he keeps trying to overcome it. And then right at the end, the way the universe finally steals his fish is, in a way is by his very own hand, by his own obsession, by his own desire to order creatures. If you were to follow that to its current end, you would see that fish was never, was never an actual grouping at all.

CURWOOD: Lulu, so then how did you come to process this idea that fish don't exist? And, and what does that mean for your life?

MILLER: The best way I can explain it, what I've slowly come to understand is what these scientists are saying is that fish is a gerrymandered category. It's a term we use, it's a proxy that we use to parse the chaos. But it is a way that we keep our sense of superiority intact. And if you want to look more closely at nature, having an openness to the sense that most of our intuitive categories might actually be wrong, can help you see the world more expansively. And so I think, for me, this, this wacky concept that fish does not exist. It's become a mantra in my mind and a reminder, to think about what other categories and hierarchies we may be believing in that we need to re examine.

CURWOOD: Lulu Miller is a cofounder of NPR's Invisibilia and the author of Why Fish Don't Exist. Lulu, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MILLER: Thank you so much, Steve.

Related links:

- Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life

- Learn more about Lulu Miller

Bruce Springsteen. “Terry’s Song” from the album Magic Columbia Records 2007

Farewell to Peter Dykstra

Peter Dykstra was a journalist who worked on environmental issues for decades, including time at CNN's Science, Tech and Weather Unit, Environmental Health News and The Daily Climate, as well as Living On Earth. He was loved by many and will be missed. (Photo: Courtesy of Peter Dykstra's family)

We interrupt this broadcast to bring you the late breaking and so sad news that our beloved colleague and friend Peter Dykstra has died at 67 in an Atlanta hospital from respiratory failure linked to pneumonia.

Almost every week for more than a decade Peter was the puckish bard of concise environmental news and histories, delivered from his home in Atlanta with a twinkle in his eye you could hear on the radio.

We’ll have a tribute to Peter Dykstra later this month, and if you’d like to say something about him as well please write to comments@loe.org.

So, for now, with a heavy heart we say, good bye Peter, we miss you and thanks for everything.

Related links:

- EHN | "Environmental journalism loses a hero"

- SEJ | "SEJ Mourns Loss of Long-Time Member Peter Dykstra"

Coming up, poetry and delights with Ross Gay but first this poem from Catherine Pierce.

“Earth, Sometimes I Try to Play It Casual”

“Earth, what I want is to sit gentle under your twilight purple.” – Catherine Pierce (Photo: Bowen Chin, Unsplash)

Earth, Sometimes I Try to Play It Casual

like Hey mercury, hey malachite, I’m busy today,

can’t stop to marvel, but always my blood is saying

O god you starsprung miracle. It’s self-preservation,

letting myself believe laundry matters,

letting myself believe there’s anything other than

egrets and oceans and vast moss carpets and

the finite heart of every single person I love.

Earth, you terrify me—you are fierce green

and honeysuckle, you are herds of wild ponies,

and you are leaving, always. Is it any wonder

some days I look at my laptop instead of out

the window? Every time I glance up

there you are, quaking me with your fern fronds

and silver frost. O you of the rhyolite mountains.

You of the dew-hung web. You are lemon quartz

and quicksand. Muskrats and starfish. How

could I be any way but staggered? O blue spruce,

O white fir, O green forever, you know

my nonchalance is a sham. It’s so hard to admit

our real desires. Earth, what I want is to sit gentle

under your twilight purple, watch your bats

hunt and dive. What I want is to know about

endings and still love each wingbeat, each shade

of the boundless, darkening sky.

Catherine Pierce is the author of four books of poems including Danger Days and The Tornado Is the World and is professor of English and co-director of the creative writing program at Mississippi State University. (Photo: Megan Bean / Mississippi State University)

That’s poet Catherine Pierce. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

Related links:

- Catherine Pierce’s website

- Find Catherine Pierce’s book of poetry, “Danger Days”, here (Affiliate link supports LOE & indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Skyforager”]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Kilkerrin”]

Ross Gay's Book of (More) Delights

Ross Gay’s The Book of (More) Delights highlights the joy one can find in everyday life and in the natural world. (Photo: Courtesy of Ross Gay and Algonquin Books)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Living on this earth can be a challenge these days.

Plenty of crises from the climate to geopolitics can make you feel blue.

But poet and essayist Ross Gay keeps creating antidotes to brighten you up.

A few years ago, he compiled The Book of Delights, loaded with moments of good that sprout amid our troubles.

And now he’s back with The Book of (More) Delights with even more scrumptious moments to savor on our complicated planet.

Hi Ross and welcome back to Living on Earth!

GAY: Thank you. It's good to see you.

CURWOOD: So this is your second Book of Delights. But what is a delight, exactly?

GAY: You know, I lately have been thinking of it as just like the sort of pleasant, fleeting, often evidence of life. That's really what I've been thinking of it as, this kind of something sweet that happens that often is surprising, that often we don't necessarily know it's delightful, but it happens and we recognize it. And that that, to me, sort of constitutes, "Oh, delight."

CURWOOD: Now, your first Book of Delights came out in 2019. Since then, a few things have happened, like the pandemic. So how did your approach change when writing this book?

Ross Gay’s work focuses on delight not only as one of the pleasures of human life, but as a source of resistance against oppression. (Photo: Natasha Komoda)

GAY: I feel like the books are, they're contemporary. They're sort of like considering what's happening day to day, they have a kind of diaristic quality to them. So I'm talking about what's happening. I think, really, the thing that changed most is that it was five years later. I had aged.

CURWOOD: Oh, my goodness, that does happen, doesn't it?

GAY: So you know, like, in the process of writing it, elders died, you know, like, my relationship with my mother is changing as we both are getting older. All kinds of things like that. The book is really a book about aging. I feel like that's one of the things that it is.

CURWOOD: Yeah, this is not television, of course, but you do have a few more gray hairs in that beard, Ross.

GAY: [LAUGHS.] It's true.

CURWOOD: Now, one of your delights is about the joy of clothes on a clothesline. My mother and grandmother loved bringing the clothes in from the line, and this one really hits home for me. I mean, she’d tell me to bury my face in the sheets—“Smell that,” she'd say. Would you mind reading that delight for us? It's on page 19.

The Book of (More) Delights reminds us that we are life. (Photo: Natasha Komoda)

GAY: Yes. "The Clothesline." There are so many simple pleasures, simple delights, and maybe the goal, the practice, is to be delighted especially by them, the simplest of things. For instance, today, among the many, I offer the clothesline, not only for its utility, how it keeps the house from getting hot in the summer, how it saves a little energy and burns a little less CO2, but also for how it reminds you that your grandma in northern Minnesota loved to hang her sheets on a clothesline in the winter for how they smelled after they froze, and that your mother loves the smell of anything hung out. But also this, I’m thinking today, as I admire my T-shirts and shorts and drawers and towels blowing in the wind like Tibetan flags, like a ramshackle and sometimes threadbare rainbow: that a clothesline reminds you how often we make of our simple daily labors (hanging clothes, folding clothes, washing dishes, arranging the fridge or the cupboards, chopping veggies or wrapping the bread, sweeping up, or mopping) an art.

CURWOOD: Indeed. Now a lot of your essays talk about finding delight in the natural world. How intentional was that? Or does it just simply kind of emerge on its own?

GAY: I think it emerged on its own. I'm a serious gardener. I love the garden. And you know, I spend a lot of time kind of paying close attention to trying to pay close attention to what's happening out there. So I think it probably just emerges by being part of what I do regularly.

CURWOOD: There's a great example of a delight about the natural world and you getting your fingers dirty in the ground. It's called "Garlic Sprouting." It's on page 145. Could you read that, please?

Author Ross Gay enjoys spending time in his garden, watching garlic sprout. (Photo: Natasha Komoda)

GAY: "Garlic Sprouting." Although I infrequently feel it when I’m planting garlic in the fall, always later than I’m supposed to (ballpark Halloween, in my book), and although this is my thirteenth consecutive year of planting garlic, during which I’ve had twelve either reasonably or exceptionally successful crops, I realized today that I plant garlic, every year, with no small degree of doubt that it will actually come up, or make, as we say in the trade. I mean, when it comes to garlic, I am batting 1.000. I should say, garlic is batting 1.000. I just hand garlic the bat. But you get my point. Though I didn’t realize, or better yet, I didn’t register, that I plant garlic doubtfully until today, as I was sitting on the back porch, because spring is springing and we’re having a warm one, and midway through a phone call I cast my gaze unexpectantly over the garlic beds and, wouldn’t you know, they were all sprouting, unsheathing a few hundred green blades up toward the sun. With the enthusiasm of someone witnessing a miracle, Lazarus waltzing from his cave or something, I interrupted the friend I was talking to, Wait, wait, yo, it’s up, it’s sprouting! The garlic’s sprouting! It’s up! (The friend seemed glad for me.) Who knew that in addition to vampires and getting your tomato sauce right, garlic’s your tiny professor of faith, your pungent don of gratitude?

CURWOOD: Indeed. I never knew that until now.

GAY: [LAUGHS.] I know, it took me a long time to realize that too. And again and again and again it feels like the garden shows me that like, oh, and this is another thing to be grateful for.

CURWOOD: One of my other favorite delights that you have is the "Squirrel in a Pumpkin." It's on page 80 And I will try to not laugh while you're reading because I don't want to mess up the recording. But could you please read it for us?

Ross Gay’s work includes books such as Inciting Joy: Essays, Be Holding, and Catalog of Unbashed Gratitude. (Photo: Courtesy of Ross Gay and Algonquin Books)

GAY: Sure. "Squirrel in a Pumpkin." On a porch, down the block, on my way, distracted from which, reminded of which, and I was very still, so the critter gobbled away though with an eye on me, which you could tell was really on me when looking down into the pumpkin for more goodies, looking at me, then looking down, then looking at me, then looking down, then looking at me one more time to be sure I guess I was not actually one of the neighborhood cats dressed up like a human being with a backpack, before plunging headlong into the gourd so that all that remained visible of the critter was that plump butt, those long-footed rear legs, and that tail, buoyant, flamboyant, and well, gaudy, even gauche, truth be told. Until popping back out of the pumpkin, eyeballing me again while working over this seed, which, to the squirrel, from the looks of it, would be like me eating a little pizza. I’m talking scale here. This squirrel was in the plumping phase of the year, not worried about spring break. And because of my job, a lucky job as far as they go, I thought, Oh, this is a delight, let me write this down. So I elegantly swiveled my backpack into my frontpack, unzipped slowly as possible, reached into the bag, and as I was pulling out my notebook, the squirrel looked at me like Oh no you don’t you cat dressed as a human, and tipped away, as they do, which might be a small but useful lesson on the differences, or perhaps the consequences, of acquiring, versus being with, or in, or of, the delight.

CURWOOD: So I love this image of make sure that one of those neighborhood cats dressed up like a human.

GAY: It's a sweet one.

CURWOOD: And then gently admonishing us to stay in the moment.

GAY: Yeah.

CURWOOD: You know, like so many of us pull out our iPhones to take a picture of something that’s going on.

GAY: I know it. I know it. That's one of the things that I sort of recognize, and people ask, also, is if the writing down of the delight is a kind of interruption of that process of being in the delight. I think it's a great question. And I also think there's some real deep impulse in us to note and share what we love. And I think that's also like a thing to really value.

Ross Gay finds delight in the simplest of tasks, like doing laundry. (Photo: Natasha Komoda)

CURWOOD: Now, you wrote a delight almost every day for an entire year, but you limit the book to 81 delights. So what makes a delight really compelling in your view?

GAY: There's probably a bunch of things. But one of the things, for sure, is if the delight comes from a question as opposed to an understanding. So if the delight sort of holds the fact that I'm wondering about what makes it delightful, as opposed to this other thing, which is like sometimes I'm delighted by something that I kind of know why, and I'm going to explain it. In a way, it almost feels like that's the simplest sort of measure of whether or not I'm going to find it interesting enough to keep. The reason that I write, as I sometimes think these days, is to unknow myself. I want to write with a kind of wonder that makes what I thought I had thought a little bit shaky. Thinking about what you love is one of the ways to do that, to think as powerfully, as closely, as sort of intensely about something. Ideally, for me, I'll come to know that whatever it is that I'm thinking about differently.

CURWOOD: By the way, you have in your book, a recipe for dandelion fritters. The delight is called “Truly Overnight Sometimes It Seems.” I'm wondering if you could please read that essay for us. It's on page 177.

Writing The Book of (More) Delights following 2019's The Book of Delights inspired Ross Gay to think more about the aging process. (Photo: Ross Gay and Algonquin Books)

GAY: "Truly Overnight Sometimes It Seems." It is truly overnight sometimes it seems that the dandelions put on their crowns, and just like that, the world is suddenly brighter, more abundant, more possible—this, of course, if you, like me, adore the dandelion, see their unmartial ranks suddenly outflanking the gloom, outflowering the doom, and if you, like me, make love (a little much?) with its absolutely usable body, body of utter benevolence, body of total beneficence, petite and profligate and gleeful lovenote: the roots for all kinds of medicine, not to mention your various probiotic, bitter, hot morning drinks (for the caffeine-weaning among us); the flowers, which are actually (get close—no, closer—you’ll see what I mean) a million flowers, which the pollinators bloom into a winged dancefloor at our feet; and the leaves, little lion’s teeth, which, in addition to throwing them into your tomato sauce or greens or smoothie or black-eyed-pea fritters, you might do like this: handful or two of leaves, chopped, flour of your choice (cornmeal, chickpea, lentil, whole wheat), onion, garlic powder, paprika, salt, baking powder, water enough to get it all to a clumpy, dandy consistency. Fry in oil on low heat. Or bake them. You can use the flowers for this, too, which can probably be a way of managing or curtailing their reproduction—they [BEEP] like bunnies: those million flowers turn into a million seeds turn into a million million dandelions turn to a million million seeds, all of which is to say, the dandelion giggles at the capitalistic (and monotheistic [No other god but me & etc.] and pop song monogomistic [no one will ever love you like I do & etc.]) myth of scarcity for which it must be destroyed, and quick!—which I have no interest in doing, for they are my most consistent, prolific, generous, trouble- and labor-free crop. I mean, when the squash bugs get the squash, and the cabbage moths the collards, and the blight the tomatoes, the dandelions are steady Freddy. They are the Draymond Greens and Marcus Smarts of the garden. The Brian Grants. The Mo Cheekses or Bobby Joneses. The Patrick Beverleys. They always show up and give their all. We need to give them their flowers! They are also little beacons of the it’ll be okay, and if they had a soundtrack, it would be “O-o-h Child.” Maybe their prettiness, by which I really mean beauty, is because their roots go so far down, they fathom the depths (which, pretty sure, also explains their nutritive profile: Kale can’t hold dandelion’s jockstrap), and those beautiful flowers are missives from the deep. Or the dark. Or the mystery. Or the unknown. Or the underworld. Whichever word we want to use today to mean the dead, or at least the dead-adjacent. Missives from the dead, these little festive blooms. To which, I don’t know about you, but I’m trying to listen.

CURWOOD: Ross, these are difficult times for some of us, maybe all of us. I mean, you think of the climate crisis, various political situations, the world does not feel to be in such a great place. And sometimes when people get depressed they, they're not necessarily interested in finding delights. How can they make the connection, get the antidote to this despair and, and sadness?

GAY: The thing that I think I could say is that it often feels like we live inside of a kind of culture of death, say economy of death, certainly. By which I mean, there's money to be made off of war. There's money to be made off of illness. There's money to be made off of precarity. It feels to me that among the things that delight does, is to remind us, as I said at the beginning, that it reminds us that we are life. It reminds us that we are among the living. And it feels to me that the reason we refuse brutality is because we savor and honor and love the sweetness. We refuse the brutality because we are being reverent to life. And it feels like delight is like a little way that we're reminded like, oh, remember life, like remember this sweetness of our connection to one another. Remember this way that we are in fact beholden to one another, and the one another as sort of grand and you know, like these, you know, when the garlic comes up. That's the evidence of being beholden to this thing called life. It seems to me that we have to remember we are in fact beholden to and we need to spend time revering.

CURWOOD: Ross Gay is a poet and author of The Book of (More) Delights. Ross, thanks so much for taking time with us today.

GAY: Thank you. It's great to talk with you.

Related links:

- Listen to our previous interview with Ross Gay

- Read more of Ross Gay’s work

- Purchase Ross Gay’s The Book of (More) Delights: Essays from Bookshop.org to support both Living on Earth and local independent bookstores

[MUSIC: Taj Mahal, “When I Feel the Sea Beneath My Soul” on Sun Rise, by Taj Mahal, Geffen Records (Rereleased by Sony Music)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Shanzay Asif, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Karen Elterman, Daniela Fahria, Swayam Gagneja, Sommer Heyman, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth