Sy Montgomery on the Brains Behind the Cluck

Air Date: Week of November 1, 2024

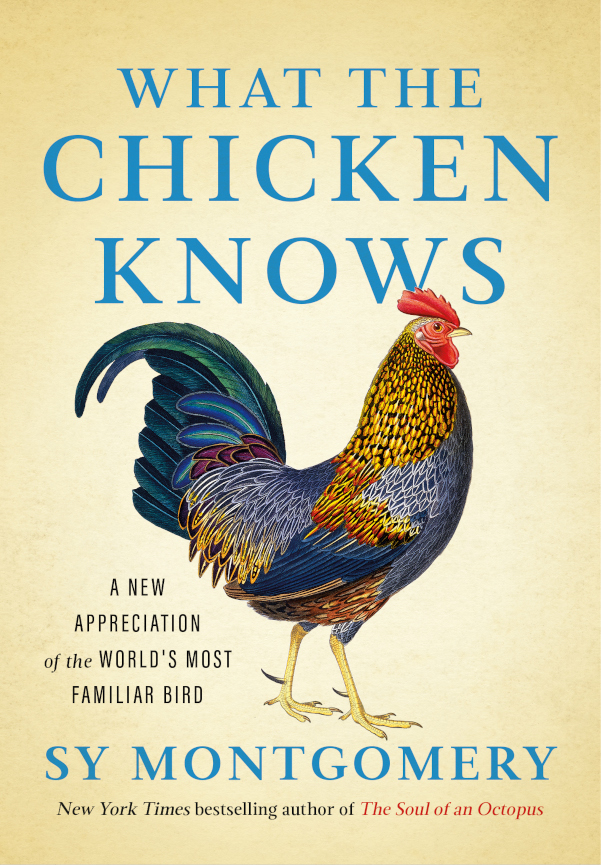

What the Chicken Knows: A New Appreciation of the World’s Most Familiar Bird by Sy Montgomery. (Photo: Atria Books)

Author and naturalist Sy Montgomery has trekked across the world to write about pink dolphins in the Amazon and tigers in Asia. But for her latest book, What the Chicken Knows: A New Appreciation of the World’s Most Familiar Bird, she stayed right in her own New Hampshire backyard. Sy sat down with Host Steve Curwood to talk about the social intelligence of chickens, how to handle a feisty rooster and much more.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Author and naturalist Sy Montgomery has trekked across the globe to write about animals. From pink dolphins in the Amazon to tigers in Asia, she’s no stranger to exotic creatures. But this time, Sy stayed right in her own backyard in New Hampshire. Her new book, What the Chicken Knows: A New Appreciation of the World’s Most Familiar Bird, takes us on a journey into what Sy Montgomery calls “The Chicken Universe.” Sy, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MONTGOMERY: Thrilled to be here with you.

CURWOOD: Always great to talk to you. I think you point out in your book that if you go to the dictionary to look up "chicken," you see it listed first as flesh, something to be eaten, not even mentioning the creature itself. And I think probably most of us, you know that's how we are acquainted with chickens, as something that goes on the dinner plate. Why should people know more about these birds in a personal way, why dedicate a whole book to them, Sy?

MONTGOMERY: Well, dead and cooked is never the best way to get to know someone. So, I kind of think it's a waste of a perfectly good friendship to cook and eat them. But chickens are the one bird that even if you can't recognize a crow, even if you can't recognize a robin, people can identify a chicken. But even though we recognize them, and everyone thinks they know a chicken, people underestimate them all the time. Chickens have a lot of wonderful things about them, but to me, the most wonderful of all is their company, and being able to travel in the chicken universe, and be able to see that even in this, you know, commonest of creatures that everyone can recognize, there is still like mystery and excitement. There's still a soul there. Each animal is highly individual, and we have so much to learn from them.

A White Bearded Silkie sports the poufy headdress that lands this breed in the “Top Hat” section of the chicken catalog. Despite the stereotypes, chickens are in fact quite intelligent. For example, they can recognize over 100 different chicken and human faces. (Photo: Tianne Strombeck)

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about the language of chickens. I suspect most of us, myself included, would just think, well, they say, bawk, bawk, bawk, bawk!

MONTGOMERY: Exactly. But you know, haven't you traveled in a foreign country, and people who are talking in their beautiful language, which has all kinds of poetry and song, it just sounds like wah, wah, wah? Remember Charlie Brown when the adults were talking? I mean, so of course, when we don't understand what's being said, it's hard to parse the words of the sentences, even of other people. So, it's no wonder that we have trouble understanding what chickens might be saying.

CURWOOD: So, what do they say?

MONTGOMERY: Well, we're just starting to decode the complexity of their chicken language. For example, we do know that chickens have a way of telling other chickens, not just that there's a predator, but is it coming on land or by air. Is it close, or is it far? But they say much more than that. They'll also say not just here's food, but here's food that you're really gonna like, versus, you know, here's some food you might want to have it. And a friend of mine discovered that her chicken had a name for her. This person, Melissa, who's written several books about chickens, which are excellent, by the way, I met her as her book was getting an award from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, as was one of my books. And her book was about chickens, and she was saying that there was one chicken in particular, her favorite chicken, Tilly, who would say something, but only when she was around. And we figured out that that was the name that Tilly had given her. Her name, by the way, was almost like a trumpet. It went like, bawk bawk bawk baaah! I mean, it was a special announcement, like, the queen is coming, get ready! And Tilly is gone now, but Tilly taught that name to other chickens who still speak her name.

The gorgeous Silver Sebright breed is named for its early 1800s originator, Sir John Sebright. Chickens also have a “language,” in which they communicate about food and predators. One of Sy’s friends even reports her chickens had a name for her. (Photo: Tianne Strombeck)

CURWOOD: So, the flock knows her name. So, these are really complex sentient beings, these chickens, is what you're telling me.

MONTGOMERY: They totally are. And the other thing that they're genius at is relationships, social relationships, and this is something that humans pride ourselves on. Oh, you know, our brains are so big because we had to keep track of our many friends and enemies as we go through our lives, but it is now known that a chicken can recognize at least 100 different faces, chicken faces and human faces. They know us and they know their friends.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about the sociology of the chicken flock. I mean, we hear things like pecking order, but that's just a tiny bit of how chickens organize themselves, I gather.

MONTGOMERY: Yes, you're absolutely right, and even the pecking order is way more about order than it is about pecking. They have best friends who they sleep next to on the roost each night. My chickens always were next to their two best friends. There is a hierarchy in a chicken flock, but it doesn't necessarily mean that there's one chicken that's getting beat up all the time. That's not necessarily the case. And even in human organizations, not everyone wants to be the top boss. Often you want to have a top boss who is looking out for hawks so they don't attack you, so that you can go about your business of laying eggs. And that's what the situation is with chickens. Often, the pecking order, the hierarchy, determines not necessarily who's going to eat first, but if there is a struggle for something really delicious, who's ultimately going to swallow it. They have culture in their flock, and each flock is different. And I discovered this when we had a new tenant who came with her own flock. Now I called my flock The Ladies. She called her flock The Rangers. And The Rangers were ready to rumble.

Sy’s former tenant, Elizabeth Kenney, with her flock, “The Rangers.” (Photo: Sy Montgomery)

CURWOOD: Uh oh, tough birds.

MONTGOMERY: Yeah, they were tough birds. In fact, even though her birds and my birds were never together outside, her birds were just cursing out my birds and threatening my birds, I could see it. And so, what did my flock do? They were a peaceful, loving group of ladies. They basically just moved next door. And I, like, never saw them, because the other birds were giving them the feather. I mean, they were giving them, giving them the finger. And even I could see that that's what those birds were doing. They were ready to rumble. And her birds too, they were such, they were so interesting. Her birds were real drama queens. My ladies, they never had strife. It was a peaceful flock. But in her flock, somebody was always getting packed, and somebody was always squawking. And so, there was definitely stuff going on in her flock that wasn't going on in my flock, and it was culture. And I found that even when I would adopt different breeds of chicken, vastly different breeds of chicken, as long as I introduced them to my existing flock, they adopted the peaceful culture of that flock. And if one chicken, for example, has befriended your neighbor, all the other chickens learn from that chicken to befriend that neighbor. They are really smart about watching everyone around them and how they act. And one of the most astonishing observations that I made was that my chicken flock understood what was going on between our house and our neighbor's house long before we did.

Sy says her flock, “The Ladies,” were a peaceful bunch. (Photo: Sy Montgomery)

CURWOOD: Wait a second. So, in other words, if you needed advice about dealing with your neighbors, you could have asked the chickens?

MONTGOMERY: Well, what happened was, for a long time, I had my flock, and there was a nice neighbor next door, and he had a nice dog who never attacked the chickens, but we didn't, like, see him socially a lot. He was just there to say hi, and you know, if he needed some help in the yard, or if we needed help in the yard, we'd help each other. Well, anyway, he moved away. That house sat vacant for a long time. The whole time the chickens never went into his yard, even though it was vacant, and I'm sure the bugs there were delicious. Then this lovely woman and her two children, seven and nine, Kate and Jane, moved in, and we became the best of friends. They met our pig, Christopher Hogwood, and they were over our house every single day. Our chicken flock then annexed their property and began going into their yard all the time. And that was when Howard and I realized that we had all become one unit, that Lilla, Kate and Jane, and Howard and I and Christopher Hogwood and our chickens and all of our other animals were part of a family, and the chickens had seen it first.

CURWOOD: So, your new book opens with the effect of the pandemic on chickens, because a lot of people went out and they started to keep chickens, and then when that moment passed, then they didn't wanna keep their chickens anymore, and they wound up in rescue facilities. Talk to me a bit about that.

Sy’s neighbor, Jarvis Coffin, gets affection from “The Ladies.” (Photo: Sy Montgomery)

MONTGOMERY: Yeah, that happened with a lot of our animals, dogs and cats as well. But so many people really wanted to kind of homestead during the pandemic, because, you know, here was a time to concentrate on home, but then they went to work, and where were their animals gonna live? And in particular, roosters got kicked out. And this is too bad, because a lot of folks who adopt chickens don't realize that 50% of those eggs turn into roosters.

CURWOOD: They do.

MONTGOMERY: And roosters are great pals, but A, they crow and not every city wants to have roosters in town, crowing and two, sometimes roosters, in an effort to protect their hens, will turn, as we had discovered when we had gotten some free exotic chicks with our order of baby chicks, and they turned out to be roosters. One day, while Howard was fixing the lawnmower…

Sy introduces her chicks to her young neighbor, Jane. Sy’s flock recognized the bond forming between the two households and expanded its territory voluntarily. (Photo: Tianne Strombeck)

CURWOOD: Your husband, Howard.

MONTGOMERY: Yes, he looked underneath the lawnmower and saw a pair of scaly spurred feet marching toward him in a menacing manner, and he knew this chicken was up to no good, so we leapt up and the rooster leapt up at him, and we knew we had a rogue rooster. But amazingly enough, just a couple of years ago, this wonderful family moved in practically across the street from me and started doing rooster rescue.

CURWOOD: Whoa.

MONTGOMERY: Yes.

CURWOOD: Rescuing these roosters that were being put out by people who didn't want a creature who crows in the morning and who, and on their legs, they have these spurs. I mean, you don't really want to mess with a rooster who, who's messing with you, right?

MONTGOMERY: No, you don't. And boy, when a rooster is on the rampage, you are reminded that birds really are dinosaurs. They are the direct descendants of the dinosaurs, and not just any dinosaurs. They're the direct descendant of the theropod dinosaurs like T Rex, the hunting dinosaurs.

Sy’s neighbor, Ashley Nagley, used to run a rooster rescue program. Here she demonstrates that the best way to calm a rogue rooster is to cuddle him. (Photo: Tianne Strombeck)

CURWOOD: Or velociraptor or something?

MONTGOMERY: Yes, absolutely. So, velociraptor probably tasted like chicken. Anyway, the spurs can be intimidating, and so can someone who can fly attacking you. But what Ashley Nagley, my neighbor, who for years had a rooster rescue, told me, is totally counter intuitive. What you want to do when a rooster attacks you? Do not run. Do not attack him back. She said, what you should do is pick him up and cuddle him, carry him around with you as you do your chores. Wisely, you probably should put his feet in some kind of a towel or a blanket to keep those spurs from hurting you, and it would be smart not to keep his beak too close to your face, but by the end of the day, you're going to have a rooster who loves you, and they can be like the best friends you ever had. They're very observant. They follow her everywhere. They watch her husband fix the car. And one rooster brings her gifts, little, shiny presents, just like crows are known to do.

CURWOOD: Smart animals. And by the way, you say that roosters are important for people who are keeping hens because of the predator problem, you have a story about that in your book.

Roosters are fierce protectors of their flock and will fight to the death in defense of their hens. (Photo: tingley, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

MONTGOMERY: Oh, boy, do I ever. Well, Howard says, if you want to see wildlife in New Hampshire, get chickens, because it's going to attract foxes. It's going to attract hawks, weasels, bobcats, skunks. We've had mink. I mean, basically everybody who can eat a chicken is going to try to eat a chicken. But roosters are quite valiant, and they will give their lives for their flock. And sometimes you can see roosters chasing off foxes. You can see roosters chasing off bobcats. Often it turns the other way, but they are steadfast defenders, and they're very good generally to their ladies. They're the ones that are always telling their ladies, look over here, I found a delicious tidbit. And they'll stand back after calling their ladies and let the ladies eat first before they do.

CURWOOD: So, who says chivalry is dead?

MONTGOMERY: Yeah, right, it's living in roosters.

CURWOOD: So, chickens are, you know, stereotypically referred to as being "bird brained", and people will say, oh, you cut their heads off, and they'll still run around. They can't be very smart. And your response obviously, already you're saying that they're pretty smart. But how badly are we really underestimating these animals?

MONTGOMERY: Well, I think enormously, because if you look at how chickens are raised on factory farms, they’re not treated like thinking, feeling creatures at all. And I remember when I first read Animal Liberation, over 40 years ago, I closed the covers and never ate meat again. That was a long time ago, and at that point, things have improved a little bit, but chickens were kept in cages so small they could hardly turn around. Their toes would grow through the mesh of their cages. They never saw sunlight or never got to interact with other chickens. It's a very bad thing when we fail to recognize that animals think and feel and know.

Inhumane practices at factory farms include cramming chickens into cages where they can barely move. (Photo: Matt MacGillivray, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, we have to sort of make chickens very dumb so we can eat them. If we really recognized how smart and powerful chickens can be, and I dare say, in your book, even loving?

MONTGOMERY: Oh yeah.

CURWOOD: Then how could we eat them?

MONTGOMERY: Exactly. Well, I know that there are home farms where chickens live a good life and then suddenly cut their heads off and eat them. I'm not interested in eating anybody these days, but I know lots of people are, and if you must eat a chicken, I would say, go to one of those farms or eat a pasture raised chicken. But don't give your hard-earned money to people who are torturing sentient beings.

CURWOOD: So, you know, many animal people have to fend off accusations of anthropomorphism or projecting human emotions and motives onto other non-human animals. So, what's your perspective on that when it comes to chickens?

Worse than anthropomorphism, Sy says, is anthropocentrism, in which we assume that we are the only creatures who think and feel. (Photo: Tianne Strombeck)

MONTGOMERY: Well, I think we constantly make that same mistake with our fellow humans. You know, we project our emotions onto each other. Who hasn't gotten a gift they thought was going to go over great for their spouse or their children and they didn't like it. Or ask someone out on a date when they really didn't want to go. So of course, that's an easy mistake to make, but worse than anthropomorphism, I think, is anthropocentrism, in which we assume that we are the only creatures that think, feel and know. And also, the unwise assumption that the way in which animals think, feel and know, is exactly the same as us. For example, chickens don't do this, but other birds feed each other by essentially throwing up into their mouths. That's a sign of great affection. That would not work for me with my husband, okay? So, you know, we would totally miss what was going on with these birds if we tried to assume that they behaved like we did. I mean, animals behave differently than we do, but I am sure that they think and feel and know. We just have to develop that beginner's mind and learn how they experience the world, rather than assume that we're the only ones who are having mental experiences or assuming that our kind of mental experiences are the only ones that matter.

Sy Montgomery is a naturalist, adventurer, and author of more than thirty acclaimed books of nonfiction for adults and children. (Photo: Vicki Steifel)

CURWOOD: Sy, in your view, what is it you think that chickens can teach us? What things can they teach us?

MONTGOMERY: Well, first of all, humility, because we misjudge them. They can teach us that all creatures have something to show, some magic to share, and that we need to be patient and pay attention to this world. Even a chicken can fill you with awe. And I think that sense of awe, that sense of connection, is something that we're all very hungry for, and a humble chicken can give that to you.

CURWOOD: Sy Montgomery, thank you so much for taking the time to come by to talk about your new book, What the Chicken Knows.

MONTGOMERY: Well thanks so much, this is a blast. I always love seeing you, Steve.

CURWOOD: Bawk, bawk, bawk!

MONTGOMERY: Bawk, bawk, bawk!

Links

Learn more about Sy Montgomery

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth