November 1, 2024

Air Date: November 1, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Climate Goal in Trouble

View the page for this story

The UN says the current plans of nations to reduce global warming emissions would result in a destructive three degrees Celsius of warming above pre-industrial levels, far higher than the 1.5 C goal set by the Paris Climate Agreement. Bob Berwyn of Inside Climate News joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss the widening gap between these plans and the ambition that’s needed to prevent catastrophic climate impacts. (10:31)

Facing the Biodiversity Crisis

View the page for this story

As the world meets in Cali, Colombia at the 2024 UN biodiversity summit, we speak with KM Reyes, co-founder of the Centre for Sustainability Philippines, in a conversation first broadcast in 2022 about how indigenous people are often vital protectors of land and biodiversity. She joined Host Steve Curwood to describe indigenous land protection on the island of Palawan in the Philippines. (09:32)

EV Chargers Good for Business

View the page for this story

Research shows that public EV charging stations bring more customers and income to nearby businesses. Tik Root, senior staff writer at Grist, joins Host Jenni Doering to explain these benefits and how businesses can take advantage of them when installing EV charging. (08:16)

Sy Montgomery on the Brains Behind the Cluck

View the page for this story

Author and naturalist Sy Montgomery has trekked across the world to write about pink dolphins in the Amazon and tigers in Asia. But for her latest book, What the Chicken Knows: A New Appreciation of the World’s Most Familiar Bird, she stayed right in her own New Hampshire backyard. Sy sat down with Host Steve Curwood to talk about the social intelligence of chickens, how to handle a feisty rooster and much more. (18:38)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

241101 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Bob Berwyn, Sy Montgomery, KM Reyes, Tik Root

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Science says we are moving too slowly to meet the Paris Climate Agreement goals, but it’s no time to give up.

BERWYN: 1.5 isn't just a sort of a trap door where everything changes all at once. It gets worse with every 10th of a degree. And so, if you can't stop warming at 1.5 degrees, it's better to stop it at 1.6 or 1.7 as soon as we possibly can.

CURWOOD: Also, back yard chickens can come with feisty roosters.

MONTGOMERY: What you ought to do when a rooster attacks you do not run, do not attack him back. What you should do is pick him up and cuddle him, carry him around with you as you do your chores. And by the end of the day, you're going to have a rooster who loves you.

CURWOOD: That’s this week on Living on Earth—stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Climate Goal in Trouble

A recent report from the United Nations admits that the goal of keeping global warming to 1.5º Celsius may now be out of reach. (Photo: Xabi Oregi, Pexels.com, public domain)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

As the world prepares for the UN climate treaty summit COP29 in Azerbaijan, a trio of scientific reports is warning that we are headed for a destructive three degrees Celsius of warming above pre-industrial levels. That’s a far cry from the 1.5 degrees Celsius goal set by the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015. With 1.3 degrees of average warming so far, our planetary fever is already spawning more catastrophic storms, heat waves, and sea level rise. To meet the Paris goal, the world needs to cut global warming emissions by nearly half by 2030, and so far, we are way off track. The continued burning of fossil fuels and the destruction of forests now has global warming gas emissions higher than ever, and the current plans of the 198 nations in the treaty add up to only a paltry reduction of 2.6 percent. Bob Berwyn who follows climate negotiations for our media partner, Inside Climate News, is here and he explains what’s required to meet Paris.

BERWYN: The annual reductions needed now are about 7.5% a year, and we're very far away from that. And each year that it doesn't drop, that percentage cut gets bigger and bigger, so we're sort of slipping away. And actually, one of the most interesting things in the three reports was a comment from senior United Nations officials who acknowledged, one of the first times that I've seen it in writing from the UN, that the 1.5-degree goal may not be reachable.

DOERING: Well, this 2.5% projected emissions reduction by 2030 it's where the world is headed collectively. But to what extent are certain countries pulling more weight here? Who is actually on track to make the most impact?

BERWYN: Probably have to single out Europe, which has decreased its emissions by about 32 and a half percent since 1990 and so is really on track to meet that 40 to 50% emissions cut by 2030. And they've in the last couple of years, have even toyed with setting a more ambitious target of 50 to 55% reductions by 2030. And the US has cut emissions by about 17% in comparison to 1990. US emissions peaked in 2007 and so there is some progress among some developed countries, but again, not as much as is needed to meet these global goals. And when you look at the EU and the US, you're looking at a huge percentage of total global emissions, along, of course, with China, which is now the leading global emitter annually, and is hopefully also gonna peak emissions at some point. Under the Paris Agreement, countries are not all tied to reducing emissions at the same rate. In fact, it's recognized under the UNFCCC framework that developed, rich industrial countries have emitted the most historically, and thus have an obligation to make the biggest cuts the soonest, too. So, it's a very tiered, complex, layered system.

With every tenth of a degree the planet warms, climate change related weather events like drought and storms will become more pronounced. (Photo: NOAA Satellites, NOAA.gov, public domain)

DOERING: You know, hearing about this gap between where we need to be in order to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius and where we're headed at the moment, I imagine some people may be feeling a bit cynical about the efficacy of the UNFCCC right now. Some might even say, why keep having these meetings if we're so far off the mark? What's your response to that?

BERWYN: Well, my response is that the UNFCCC process did deliver the Paris Climate Agreement, which 198 countries agreed to. I suppose, going into COP29 you can say it's good that we still have 198 countries at the table talking about this and at least in principle, agreeing that it's important and that something needs to be done. At COP28 last year, we had a statement about transitioning away from fossil fuels, finally. That was COP28, so that was after 27 years of climate summits. And it's not very specific, but it was, you know, it was hailed as a huge success. And there are studies out there showing that emissions globally would probably be higher, quite a bit higher, if we didn't have these global climate talks ongoing since the early 1990s. So, they have managed something. I mean, think about it, we might already be at two degrees warming now, instead of 1.2 degrees if we hadn't initiated these efforts.

You know, look back to the Kyoto Protocol in the early 2000s, some countries took that really seriously. And I'm going to use Europe as an example, again, because I'm based here, and I'm a bit familiar with it. They took the goals of the Kyoto Protocol and kind of started working on them right away. And even when it fell apart, they said, well, this isn't our interest, and we're going to continue on this path. And so now they're sort of set to meet these next level climate targets that kind of come from the Paris Agreement. And I think that shows the benefit of persistence and incremental efforts and incremental improvements. And at the same time, things are getting worse fast, and it really is a climate emergency, a climate crisis, if you will. And I think we've seen that in the last few months in so many different ways. So there needs to be an urgency too. And I'm afraid that people will say, well, okay, well, then shoot, we'll just aim for two degrees and wow, that gives us a few more decades to kind of ease off, and, you know, hopefully invent some new technology that will help get us out of this mess.

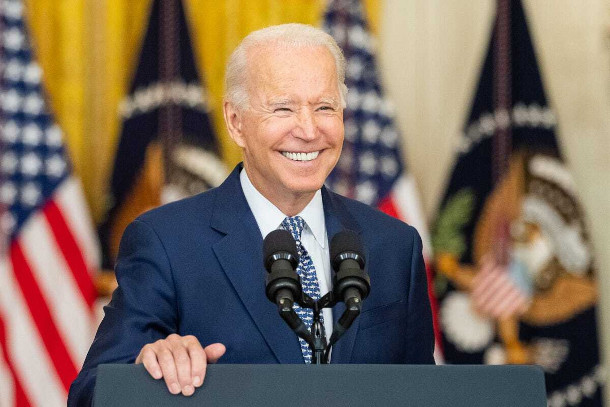

The international community is accustomed to the United States flipping back and forth between climate policies. The Clinton Administration of Democrats declined to sign the final Kyoto Protocol and submit it to the Senate for ratification. Former Republican President Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Agreement. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: You mentioned that one of these reports grappled with the very real possibility that the world will overshoot 1.5 degrees Celsius at some point, of warming. What then? What happens if we go past that point?

BERWYN: There's still lots of scientific discussion about what happens at those different levels of warming, but one thing is for sure, that the impacts from these increases are incremental. You know, some of these numbers don't sound like that much, you know, the difference between 1.5 and 1.6. But we know now, from climate science done just in the last few years, that small increments of warming make heat waves worse by magnitudes. A few tenths of degree in warmer ocean temperatures loads up hurricanes with that much more moisture, that makes that much more rainfall and can make the wind stronger as well, and so the impacts don't increase by these tiny increments. They're magnified many times over each time the increment goes up a little bit. But we still have to do everything we can to limit warming, because 1.5 isn't just sort of a trap door where everything changes all at once. It gets worse with every tenth of a degree, and so if you can't stop warming at 1.5 degrees, it's better to stop it at 1.6 or 1.7 as soon as we possibly can.

DOERING: So, we're speaking on the eve of the US presidential election. What's the mood like in the international community about how this election might shape the next few years, or even decades of global climate action?

While some from European countries believe that a win for the Democratic party will keep the U.S. on track for climate pledges, African experts say it won’t much affect them one way or the other. (Photo: United States Senate, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

BERWYN: I'd say that there's a pretty wide range of reactions from different parts of the world. You know, with close trade partners like Europe, where we've shared sort of a somewhat common climate policy, there's great concern that the election outcome will affect what happens over the next few years. It's pretty clear from the candidates in the US, their positions on energy and so forth, that a Republican win would probably result in more emissions, and a Democratic win would result in, you know, continued reductions, at least moderate, and maybe more. In other parts of the world, I spoke with a couple of climate economists in Africa over the last few months, and they don't really have as big a stake in it as some other regions of the world. Some of the comments I heard, well, the US doesn't really have any cohesive strategy or climate interests in Africa, other than perhaps, you know, getting minerals for the energy transition. So, they didn't feel that the outcome would have a really direct, strong effect on them. They may be right, or they may be wrong, depending on what happens.

Bob Berwyn is a reporter based in Europe for Inside Climate News. (Photo: Courtesy of Bob Berwyn)

But one overriding sense that I got is that the world is pretty used to the US kind of reversing course on climate policy every now and then. I mean, that's the only country that's pulled out of the Paris Agreement, then rejoined. It also refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol. And so, I don't think a reversal of US course would be a big surprise to a lot of people. And there's a consensus that, you know, the rest of the world is going to truck along and continue. The global climate effort will definitely be slowed, it can be delayed by US non-participation, or possibly even, you know, interference in promotion of fossil fuels, let's say, rather than trying to reduce them. But the rest of the world, with the exception of a few other countries, are gonna keep trying to do this because they all know that it's critical and that it's in their own interest to do it. In fact, some climate economists said that the US runs the risk of sort of ending up like a rusty locomotive on a railroad siding in terms of the energy transition. It's gonna leave the US isolated at some point in a world that has moved on beyond fossil fuels.

DOERING: Bob Berwyn is a reporter with our media partner Inside Climate News, based in Austria. Thank you so much, Bob.

BERWYN: You're very welcome.

Related links:

- Read Berwyn’s article in Inside Climate News

- Explore COP29

- Learn more about the Paris Agreement

- Is the Paris Goal of Keeping Below the 1.5C Limit Out of Reach?

[MUSIC: Junior Mance “Whisper Not” on Jubilation, Wnts]

CURWOOD: Just ahead, research finds that EV charging stations give nearby businesses a boost. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Junior Mance “Blues for Beverlee” on Jubilation, Wnts]

Facing the Biodiversity Crisis

Palawan Island is the largest in the Philippines and is known as “The Last Ecological Frontier of the Philippines." (Photo: Patrick Kranzmüller, Flickr, CC_BY_NC_ND_2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

According to the United Nations, some 1 million species are at risk of going extinct within decades. To try to avert that grim future, the world’s nations are meeting in Cali, Colombia, at the 2024 UN biodiversity summit known as COP16. The last round of talks in 2022 yielded an agreement to protect 30% of the earth’s lands and oceans by 2030, simply known as “30 by 30.” But protecting those vast areas isn’t as simple as putting up a “keep out” sign, because humans, especially indigenous peoples, are often vital protectors of land. In 2022 Filipino conservationist KM Reyes joined us to discuss how indigenous practices can safeguard biodiversity. Here’s an excerpt from our conversation.

REYES: Yeah, so the Philippines is one of only 17 mega-biodiverse countries on the planet. It was previously 95% covered in pristine rainforest, and now only 3% is left.

CURWOOD: Whoa, wait, you've lost all but the last 3%?

REYES: Yes, of pristine rainforest.

CURWOOD: Wow. Okay.

REYES: And even though we only have 3% of pristine rainforest left, we actually still have the most vertebrate diversity on the planet. So, we're a really small country, we're made up of 7,000 islands. But we still have incredible biodiversity across our islands, and also in our oceans, so our coral reefs and our seas. We have all sorts of really charismatic wildlife and ocean fauna, from thresher sharks to the Philippine pangolin, which is critically endangered and the number one poached animal globally. And this area is also this perfect meeting place of volcanoes and the Coral Triangle. So, it's a meeting place for all sorts of different, you know, tectonic movements that happened. And that's why we are also really mega biodiverse. And the reason why this specific treaty is so important for us in the Philippines is if we don't have a good global strategy, then we don't have a national strategy to build off. And obviously, as a conservationist, I want the strongest possible policies at the international level, as well as at the national level. And if we're going to reach our biodiversity targets, if we're going to reach these very ambitious goals, we need adequate financing to do it, especially with something like 30 by 30, that requires a lot of follow up monitoring and management of these protected areas.

Palawan Pangolin. Pangolins are among the most critically endangered animals due to heavy poaching and worldwide trafficking. (Photo: John Christian Yayen)

CURWOOD: Tell me a bit more about the role of the Global North here and why financing is necessary to help protect the biological diversity in the Philippines.

REYES: Yeah, so a lot of the environmental destruction is often caused by Global North and industries in the Global North. And so, there is a lot of importance here on ensuring that the Global North also pays their dues. For example, you know, we're working on a protected area in Palawan. And we're up against a mining company that is Canadian, funnily enough. And so, these are the kinds of international and kind of transnational issues that we deal with when trying to protect biodiversity. And so, it's extremely important that the Global North really takes responsibility for the footprint that they're making on biodiversity in different areas, especially in the Global South. And you will see this across mega-biodiverse, you know, Global South countries, the Democratic Republic of Congo is another classic example, whether it's cobalt or nickel, or, you know, other kinds of minerals. And specifically in the Philippines, the big issue that we're dealing with is that we're very rich in nickel. And so, this is obviously a key mineral for the electric car revolution. And so, for us, in the Philippines, it's very far away in our timeline that we're going to have access to these electric cars, right? A lot of these electric cars will go to Europe and North America, but they're coming from and destroying biodiversity in Global South countries like the Philippines.

Indigenous Batak mothers of Manggapin. (Photo: Jessa Garibay)

CURWOOD: Now, what about the Indigenous communities living within the islands there, what's their role in protecting biological diversity?

REYES: So Indigenous peoples globally represent 5% of total population and protect 80% of global biodiversity. So Indigenous peoples and local communities play an outsized role in ensuring that biodiversity continues. And actually, the reason why we still have biodiversity now is because of our Indigenous peoples and local communities that are living in and around our frontlines and protecting these areas, whether it's freshwater and salmon runs to pristine rainforest. Certainly, in the area that we protected, at Cleopatra's Needle Critical Habitat, this is home to the disappearing Batak tribe, there's only 200 people left of this ethnic group, and they have protected this area since time immemorial. So, wherever we are in the world, Indigenous peoples and local communities are the key to ensuring that these areas are protected, and biodiversity is retained.

Batak women and children in traditional dress. (Photo: Jessa Garibay-Yayen)

CURWOOD: Yeah, tell me more about Cleopatra's Needle. Your organization, the Center for Sustainability PH worked on helping to protect this area. Why is it so important?

REYES: Cleopatra's Needle Critical Habitat is the Philippines' biggest critical habitat. It's the size of the City of Montreal, so some 41,350 hectares, and it's the highest peak of our city, Puerto Princesa city. It's about 1500 meters above sea level, it takes about four days to hike up to the peak because it's extremely difficult terrain to get up. And it's pristine rainforest, as I mentioned, that is the ancestral home of the Indigenous Batak tribe. And with summary scientific research, we've already been able to identify that it's home to 61 Palawan endemic species and 31 globally threatened IUCN species. So, it's an area of extremely important biological diversity. And it's also very important as a critical habitat, because this is habitat that's critical for the survival of a very, very special and threatened species globally, not just in the Philippines. So, this area is magical. It's, you know, flowing rivers and pristine rainforest, the hiking is incredible. It's an area that has many, many sacred spots, and is tied with the culture and tradition of the Indigenous Batak community. And I think without their stewardship, we would not have Cleopatra's Needle, for sure. And also, without this forest remaining, the Batak people would also not survive, they are so tied with this forest that for them, their existence could not be without it. And so, for example, you know, their naming of how they name their children is always about, what are the natural things that are around them at the time of birth. So sometimes they're named after the tree that they're born under, or the weather on the day of their birth. It's very much tied in with specifically this rainforest.

A Batak woman washing clothes in the river. (Photo: Robin Moore)

CURWOOD: By the way, why is it called Cleopatra's Needle? That doesn't sound like an Indigenous term to me anyway!

REYES: Yeah, so Cleopatra's Needle is a military name that came from the US, because it was the US military that mapped most of our island, but it does actually have an Indigenous name. So, Cleopatra's Needle is named after the obelisk peak of the mountain, but Puyos ni Bayi is the Indigenous name. And this means the hair bun of Bayi. So Bayi is a common foremother of the Indigenous Batak people, so generations before she was seen as the foremother of their people. And puyos means hair bun. So, they see it as the hair bun at the top. And that's what makes it so pointy. And so, they see Bayi as the protector of this forest. So internally, we talk about it as Puyos ni Bayi, but internationally, it's called Cleopatra's Needle.

A Batak woman and children fish in the river. (Photo: Robin Moore)

CURWOOD: KM Reyes is Co-Founder of the Centre for Sustainability Philippines. Since we spoke with her in 2022 there have been legal challenges to mining on the island of Palawan, and in 2023 the Philippine Supreme Court ordered a nickel mining venture there to take proper care of the environment and people. The UN biodiversity conference COP16 is scheduled to wrap up on Nov. 1 and during next week’s broadcast we plan to dive into what took place, so don’t forget to tune in!

Burned rainforest near Cleopatra’s Needle in the Philippines. (Photo: Jessa Garibay-Yayen)

KM Reyes is a conservation lobbyist, community organizer, and National Geographic Explorer, based on Palawan Island, the Philippines. She’s the Co-Founder & Advisor of the environmental non-government organization, Centre for Sustainability PH, which she co-founded together with a small group of local colleagues. Their mission is to conserve the Philippines’ last remaining 3% of pristine rainforest through the legal establishment of protected areas. (Photo: Courtesy of KM Reyes)

Related links:

- Centre for Sustainability PH Instagram

- Learn more about Centre for Sustainability

- Centre for Sustainability video

- Learn more about KM Reyes

[MUSIC: Rob Harris, “More Lemon Juice” Single, Harritoons]

EV Chargers Good for Business

Even as EVs' popularity grows, functioning charging ports are still difficult to find in some parts of the country. (Photo: Michael Quinn, NPS Photo, Picryl.com, public domain)

DOERING: On a road trip in an EV, you can’t just fill up anywhere. The US is still building out a reliable public charging network, and according to Pew Research, with two and half million electric vehicles on the road in the US there are only 61,000 publicly available places to plug in. To jumpstart the needed buildout, in late August the Biden administration announced a fresh round of grants to the tune of $521 million, funded in part by the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. And recent research suggests that these charging stations will not only power the next generation of cars, but also boost nearby businesses. That might explain why companies like Walmart, Starbucks and Subway are adding EV chargers in their parking lots. Tik Root is a senior staff writer at Grist who reported on this research and joins us now. Hi Tik and welcome to Living on Earth!

ROOT: Hi, thanks for having me.

DOERING: So, as you wrote in your article, research suggests that having EV chargers nearby may give a boost to businesses. What were the findings of that research?

ROOT: So, the one study found there was roughly a $1,500 a year annual increase, and another found there was a roughly 4% increase in visitors. And one of those studies found that the rough distance was around 500 feet, that those chargers need to be within the business to have that effect.

DOERING: Right? Because the idea is, you plug your vehicle in. You are on foot at that point, wandering around getting a bite to eat, but you got to be back and unplug when you're done charging.

ROOT: Yeah, I think that's the idea. The researchers were telling me that they saw the most benefit for businesses whose services overlap with the charge time, anywhere from 20 minutes to an hour or so, which makes sense to me.

DOERING: And what types of businesses are installing EV chargers?

ROOT: So, I think you see them everywhere. I mean, at least anecdotally, from me driving around, I see them at everything from shopping malls to movie theaters to my local co-op, I think has a few EV chargers. But I think one of the places where I've heard that it makes the most sense, is convenience store type locations, they tend to also have disproportionately a lot of EV chargers.

DOERING: And why is that, do you think?

ROOT: I think they're usually located along transportation corridors, interstates, areas with high volume, so I think it's places where people will be needing to charge is, I guess, the idea.

DOERING: Right, because oftentimes people who use an EV would be able to charge at home, and then when they're on a road trip they would need to be able to stop and charge.

ROOT: Yeah, exactly. And my dad's an EV driver, and I've heard him stop at everywhere from a national park to a Subway sandwich shop.

DOERING: And you spoke with one of these stakeholders who's actually working on getting some of these chargers in, someone who works at this line of convenience stores called RaceTrac in the South. What were they grappling with as they considered whether to add these chargers?

RaceTrac, a southern convenance store chain installed EV chargers at some of its locations, boosting business. (Photo: Harrison Keely, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

ROOT: I think they had a few different factors. One big one was how to make money on actually selling electrons and making sure they could make that a profitable business. And a big part of that is that they have a complex input from the utility company in the way that they're charged. They're charged both connection fees, they're charged for the amount of energy they use, and they're charged for peak demand when they use it. And so, there's a whole bunch of factors that they have to weigh when deciding how much to charge a customer to charge as well. It's something they've grappled with. And others in the industry have told me that people have played with everything from time of day pricing to dynamic pricing, like Uber, to static pricing. And so, there's a lot of development in that field about how to charge customers for charging, so there's been some changes on that front. And then they are also looking at incentives from not only utilities but also the federal government that could help them install these chargers, which can be expensive. Level two chargers can run in the 10s of thousands of dollars to install and level three chargers can go into the hundreds of thousands, depending on the project. And you're seeing the federal government step in, the Biden administration has put billions of dollars towards rapidly expanding the EV network by 2030. And they've started to release grants to places Racetrack, for example, that I think it's nearly $700,000 to put in a few of these chargers. And so, this upfront money from the government, I think, is going to spur a lot of installations of new charges.

DOERING: And what are those different types of chargers, level two versus three?

ROOT: Yeah. So, level one chargers, just to start, they are the basic ones that you can plug into any outlet, and basically are slow trickle. They take a very long time to charge. We have a plug-in hybrid electric, and the level one charger takes about 12 hours to charge our car overnight. Well, we have a level two at our house. And so, the level two is basically a 220 outlet at your house, the same thing a dryer would run off of. And that takes about four hours on my car. And then my car is not compatible with level three charging. But level three is the fastest kind of charging, and those are the ones that can go from, say, 20 to 80% charged in a matter of half an hour or so depending on the car.

The Biden administration has set aside billions of dollars to build America’s EV charging infrastructure. Some of their grants are enabling local businesses to install chargers and reap the financial benefits. (Photo: Adam Schultz, Official White House Photo, public domain)

DOERING: So, what's going on at a business that's deciding which kind of charger to put in near their business? So, for example, when you talked with this person from RaceTrac, this line of convenience stores, how did they decide what ultimately was the kind of charger they were going to put in?

ROOT: I think most places that are trying to keep you there for 20 minutes, 30 minutes or so, would have to install a level three charger. A level two charger just wouldn't do much good for somebody who's on a road trip. You'd have to really be there for a few hours or so. I think predominantly convenience stores, etc., are putting in level three chargers. And then I think some places, like my local ski area, for example, has level two chargers because it's somewhere that you might be for 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, hours at a time. And I've seen level two chargers at malls. I think it's very much a use case situation.

DOERING: Having these chargers can be attractive to people who are on the road. They may be more likely, according to this research, to go into a nearby business. So, what are businesses doing to try and sweeten the deal for consumers?

ROOT: I think you're seeing a lot of businesses install the chargers. That's probably the first and most important thing they can do, is actually have one. And then I've seen everything from free charging for a certain amount of time to discounted charging. My ski area offers free charging when I'm skiing. There's a brewery in town that offers free charging. So, I think it's something that companies are grappling a lot with. I think you'll see that continue to evolve over time as more and more data becomes available. Internal combustion cars have been around for 100 plus years, and we're still in sort of the infancy of electric vehicles, so I think companies are still figuring out exactly what their approach will be, but it's interesting to watch them go about it.

Tik Root is a senior staff writer at Grist. He recently wrote an article about how nearby EV chargers boost business’ profits. (Photo: Mark Thiessen, National Geographic)

DOERING: So, what are the long-term implications of this research, and how might it shape the way EV chargers get built out across the country?

ROOT: One thing is it sort of dispels any notion that a business has to make some sort of tradeoff between being EV friendly and making money. Clearly, there are ways to do both of those things, which I think was apparent to some, but maybe not all businesses involved. Even for companies or businesses that may not have any interest in the other benefits of electric vehicles, they can at least know that they can potentially attract customers and at least sell the electricity in the way that it's profitable. That, in itself, takes some of the economics arguments against doing this off the table. It shows that we could potentially be poised for a big jump in EV charging stations in the future here. But of course, it's chicken or the egg, and you've seen EV sales start to slow. Perhaps you'll see some calibration as EV sales change, but it seems like the money, federally, at least, to install these charging stations, is there.

DOERING: Tik Root is a senior staff writer at Grist. Thank you so much, Tik.

ROOT: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Read the original Grist story

- Learn about how you can receive a tax credit if you purchase an EV

- Get advice on how to take a road trip in an EV

[MUSIC: The Beach Boys, “Fun, Fun, Fun” on 50 Big Ones: Greatest Hits, Capitol Records, LLC]

CURWOOD: Coming up, author Sy Montgomery on why chickens are far more intelligent than we give them credit for. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Junor Mance, “A Smooth One” on Junior, The Verve Music Group]

Sy Montgomery on the Brains Behind the Cluck

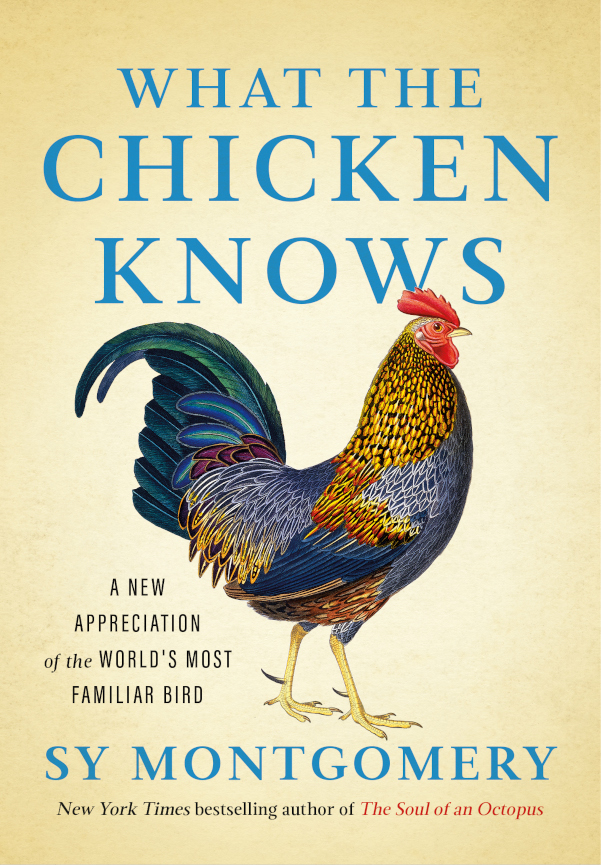

What the Chicken Knows: A New Appreciation of the World’s Most Familiar Bird by Sy Montgomery. (Photo: Atria Books)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Author and naturalist Sy Montgomery has trekked across the globe to write about animals. From pink dolphins in the Amazon to tigers in Asia, she’s no stranger to exotic creatures. But this time, Sy stayed right in her own backyard in New Hampshire. Her new book, What the Chicken Knows: A New Appreciation of the World’s Most Familiar Bird, takes us on a journey into what Sy Montgomery calls “The Chicken Universe.” Sy, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MONTGOMERY: Thrilled to be here with you.

CURWOOD: Always great to talk to you. I think you point out in your book that if you go to the dictionary to look up "chicken," you see it listed first as flesh, something to be eaten, not even mentioning the creature itself. And I think probably most of us, you know that's how we are acquainted with chickens, as something that goes on the dinner plate. Why should people know more about these birds in a personal way, why dedicate a whole book to them, Sy?

MONTGOMERY: Well, dead and cooked is never the best way to get to know someone. So, I kind of think it's a waste of a perfectly good friendship to cook and eat them. But chickens are the one bird that even if you can't recognize a crow, even if you can't recognize a robin, people can identify a chicken. But even though we recognize them, and everyone thinks they know a chicken, people underestimate them all the time. Chickens have a lot of wonderful things about them, but to me, the most wonderful of all is their company, and being able to travel in the chicken universe, and be able to see that even in this, you know, commonest of creatures that everyone can recognize, there is still like mystery and excitement. There's still a soul there. Each animal is highly individual, and we have so much to learn from them.

A White Bearded Silkie sports the poufy headdress that lands this breed in the “Top Hat” section of the chicken catalog. Despite the stereotypes, chickens are in fact quite intelligent. For example, they can recognize over 100 different chicken and human faces. (Photo: Tianne Strombeck)

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about the language of chickens. I suspect most of us, myself included, would just think, well, they say, bawk, bawk, bawk, bawk!

MONTGOMERY: Exactly. But you know, haven't you traveled in a foreign country, and people who are talking in their beautiful language, which has all kinds of poetry and song, it just sounds like wah, wah, wah? Remember Charlie Brown when the adults were talking? I mean, so of course, when we don't understand what's being said, it's hard to parse the words of the sentences, even of other people. So, it's no wonder that we have trouble understanding what chickens might be saying.

CURWOOD: So, what do they say?

MONTGOMERY: Well, we're just starting to decode the complexity of their chicken language. For example, we do know that chickens have a way of telling other chickens, not just that there's a predator, but is it coming on land or by air. Is it close, or is it far? But they say much more than that. They'll also say not just here's food, but here's food that you're really gonna like, versus, you know, here's some food you might want to have it. And a friend of mine discovered that her chicken had a name for her. This person, Melissa, who's written several books about chickens, which are excellent, by the way, I met her as her book was getting an award from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, as was one of my books. And her book was about chickens, and she was saying that there was one chicken in particular, her favorite chicken, Tilly, who would say something, but only when she was around. And we figured out that that was the name that Tilly had given her. Her name, by the way, was almost like a trumpet. It went like, bawk bawk bawk baaah! I mean, it was a special announcement, like, the queen is coming, get ready! And Tilly is gone now, but Tilly taught that name to other chickens who still speak her name.

The gorgeous Silver Sebright breed is named for its early 1800s originator, Sir John Sebright. Chickens also have a “language,” in which they communicate about food and predators. One of Sy’s friends even reports her chickens had a name for her. (Photo: Tianne Strombeck)

CURWOOD: So, the flock knows her name. So, these are really complex sentient beings, these chickens, is what you're telling me.

MONTGOMERY: They totally are. And the other thing that they're genius at is relationships, social relationships, and this is something that humans pride ourselves on. Oh, you know, our brains are so big because we had to keep track of our many friends and enemies as we go through our lives, but it is now known that a chicken can recognize at least 100 different faces, chicken faces and human faces. They know us and they know their friends.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about the sociology of the chicken flock. I mean, we hear things like pecking order, but that's just a tiny bit of how chickens organize themselves, I gather.

MONTGOMERY: Yes, you're absolutely right, and even the pecking order is way more about order than it is about pecking. They have best friends who they sleep next to on the roost each night. My chickens always were next to their two best friends. There is a hierarchy in a chicken flock, but it doesn't necessarily mean that there's one chicken that's getting beat up all the time. That's not necessarily the case. And even in human organizations, not everyone wants to be the top boss. Often you want to have a top boss who is looking out for hawks so they don't attack you, so that you can go about your business of laying eggs. And that's what the situation is with chickens. Often, the pecking order, the hierarchy, determines not necessarily who's going to eat first, but if there is a struggle for something really delicious, who's ultimately going to swallow it. They have culture in their flock, and each flock is different. And I discovered this when we had a new tenant who came with her own flock. Now I called my flock The Ladies. She called her flock The Rangers. And The Rangers were ready to rumble.

Sy’s former tenant, Elizabeth Kenney, with her flock, “The Rangers.” (Photo: Sy Montgomery)

CURWOOD: Uh oh, tough birds.

MONTGOMERY: Yeah, they were tough birds. In fact, even though her birds and my birds were never together outside, her birds were just cursing out my birds and threatening my birds, I could see it. And so, what did my flock do? They were a peaceful, loving group of ladies. They basically just moved next door. And I, like, never saw them, because the other birds were giving them the feather. I mean, they were giving them, giving them the finger. And even I could see that that's what those birds were doing. They were ready to rumble. And her birds too, they were such, they were so interesting. Her birds were real drama queens. My ladies, they never had strife. It was a peaceful flock. But in her flock, somebody was always getting packed, and somebody was always squawking. And so, there was definitely stuff going on in her flock that wasn't going on in my flock, and it was culture. And I found that even when I would adopt different breeds of chicken, vastly different breeds of chicken, as long as I introduced them to my existing flock, they adopted the peaceful culture of that flock. And if one chicken, for example, has befriended your neighbor, all the other chickens learn from that chicken to befriend that neighbor. They are really smart about watching everyone around them and how they act. And one of the most astonishing observations that I made was that my chicken flock understood what was going on between our house and our neighbor's house long before we did.

Sy says her flock, “The Ladies,” were a peaceful bunch. (Photo: Sy Montgomery)

CURWOOD: Wait a second. So, in other words, if you needed advice about dealing with your neighbors, you could have asked the chickens?

MONTGOMERY: Well, what happened was, for a long time, I had my flock, and there was a nice neighbor next door, and he had a nice dog who never attacked the chickens, but we didn't, like, see him socially a lot. He was just there to say hi, and you know, if he needed some help in the yard, or if we needed help in the yard, we'd help each other. Well, anyway, he moved away. That house sat vacant for a long time. The whole time the chickens never went into his yard, even though it was vacant, and I'm sure the bugs there were delicious. Then this lovely woman and her two children, seven and nine, Kate and Jane, moved in, and we became the best of friends. They met our pig, Christopher Hogwood, and they were over our house every single day. Our chicken flock then annexed their property and began going into their yard all the time. And that was when Howard and I realized that we had all become one unit, that Lilla, Kate and Jane, and Howard and I and Christopher Hogwood and our chickens and all of our other animals were part of a family, and the chickens had seen it first.

CURWOOD: So, your new book opens with the effect of the pandemic on chickens, because a lot of people went out and they started to keep chickens, and then when that moment passed, then they didn't wanna keep their chickens anymore, and they wound up in rescue facilities. Talk to me a bit about that.

Sy’s neighbor, Jarvis Coffin, gets affection from “The Ladies.” (Photo: Sy Montgomery)

MONTGOMERY: Yeah, that happened with a lot of our animals, dogs and cats as well. But so many people really wanted to kind of homestead during the pandemic, because, you know, here was a time to concentrate on home, but then they went to work, and where were their animals gonna live? And in particular, roosters got kicked out. And this is too bad, because a lot of folks who adopt chickens don't realize that 50% of those eggs turn into roosters.

CURWOOD: They do.

MONTGOMERY: And roosters are great pals, but A, they crow and not every city wants to have roosters in town, crowing and two, sometimes roosters, in an effort to protect their hens, will turn, as we had discovered when we had gotten some free exotic chicks with our order of baby chicks, and they turned out to be roosters. One day, while Howard was fixing the lawnmower…

Sy introduces her chicks to her young neighbor, Jane. Sy’s flock recognized the bond forming between the two households and expanded its territory voluntarily. (Photo: Tianne Strombeck)

CURWOOD: Your husband, Howard.

MONTGOMERY: Yes, he looked underneath the lawnmower and saw a pair of scaly spurred feet marching toward him in a menacing manner, and he knew this chicken was up to no good, so we leapt up and the rooster leapt up at him, and we knew we had a rogue rooster. But amazingly enough, just a couple of years ago, this wonderful family moved in practically across the street from me and started doing rooster rescue.

CURWOOD: Whoa.

MONTGOMERY: Yes.

CURWOOD: Rescuing these roosters that were being put out by people who didn't want a creature who crows in the morning and who, and on their legs, they have these spurs. I mean, you don't really want to mess with a rooster who, who's messing with you, right?

MONTGOMERY: No, you don't. And boy, when a rooster is on the rampage, you are reminded that birds really are dinosaurs. They are the direct descendants of the dinosaurs, and not just any dinosaurs. They're the direct descendant of the theropod dinosaurs like T Rex, the hunting dinosaurs.

Sy’s neighbor, Ashley Nagley, used to run a rooster rescue program. Here she demonstrates that the best way to calm a rogue rooster is to cuddle him. (Photo: Tianne Strombeck)

CURWOOD: Or velociraptor or something?

MONTGOMERY: Yes, absolutely. So, velociraptor probably tasted like chicken. Anyway, the spurs can be intimidating, and so can someone who can fly attacking you. But what Ashley Nagley, my neighbor, who for years had a rooster rescue, told me, is totally counter intuitive. What you want to do when a rooster attacks you? Do not run. Do not attack him back. She said, what you should do is pick him up and cuddle him, carry him around with you as you do your chores. Wisely, you probably should put his feet in some kind of a towel or a blanket to keep those spurs from hurting you, and it would be smart not to keep his beak too close to your face, but by the end of the day, you're going to have a rooster who loves you, and they can be like the best friends you ever had. They're very observant. They follow her everywhere. They watch her husband fix the car. And one rooster brings her gifts, little, shiny presents, just like crows are known to do.

CURWOOD: Smart animals. And by the way, you say that roosters are important for people who are keeping hens because of the predator problem, you have a story about that in your book.

Roosters are fierce protectors of their flock and will fight to the death in defense of their hens. (Photo: tingley, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

MONTGOMERY: Oh, boy, do I ever. Well, Howard says, if you want to see wildlife in New Hampshire, get chickens, because it's going to attract foxes. It's going to attract hawks, weasels, bobcats, skunks. We've had mink. I mean, basically everybody who can eat a chicken is going to try to eat a chicken. But roosters are quite valiant, and they will give their lives for their flock. And sometimes you can see roosters chasing off foxes. You can see roosters chasing off bobcats. Often it turns the other way, but they are steadfast defenders, and they're very good generally to their ladies. They're the ones that are always telling their ladies, look over here, I found a delicious tidbit. And they'll stand back after calling their ladies and let the ladies eat first before they do.

CURWOOD: So, who says chivalry is dead?

MONTGOMERY: Yeah, right, it's living in roosters.

CURWOOD: So, chickens are, you know, stereotypically referred to as being "bird brained", and people will say, oh, you cut their heads off, and they'll still run around. They can't be very smart. And your response obviously, already you're saying that they're pretty smart. But how badly are we really underestimating these animals?

MONTGOMERY: Well, I think enormously, because if you look at how chickens are raised on factory farms, they’re not treated like thinking, feeling creatures at all. And I remember when I first read Animal Liberation, over 40 years ago, I closed the covers and never ate meat again. That was a long time ago, and at that point, things have improved a little bit, but chickens were kept in cages so small they could hardly turn around. Their toes would grow through the mesh of their cages. They never saw sunlight or never got to interact with other chickens. It's a very bad thing when we fail to recognize that animals think and feel and know.

Inhumane practices at factory farms include cramming chickens into cages where they can barely move. (Photo: Matt MacGillivray, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, we have to sort of make chickens very dumb so we can eat them. If we really recognized how smart and powerful chickens can be, and I dare say, in your book, even loving?

MONTGOMERY: Oh yeah.

CURWOOD: Then how could we eat them?

MONTGOMERY: Exactly. Well, I know that there are home farms where chickens live a good life and then suddenly cut their heads off and eat them. I'm not interested in eating anybody these days, but I know lots of people are, and if you must eat a chicken, I would say, go to one of those farms or eat a pasture raised chicken. But don't give your hard-earned money to people who are torturing sentient beings.

CURWOOD: So, you know, many animal people have to fend off accusations of anthropomorphism or projecting human emotions and motives onto other non-human animals. So, what's your perspective on that when it comes to chickens?

Worse than anthropomorphism, Sy says, is anthropocentrism, in which we assume that we are the only creatures who think and feel. (Photo: Tianne Strombeck)

MONTGOMERY: Well, I think we constantly make that same mistake with our fellow humans. You know, we project our emotions onto each other. Who hasn't gotten a gift they thought was going to go over great for their spouse or their children and they didn't like it. Or ask someone out on a date when they really didn't want to go. So of course, that's an easy mistake to make, but worse than anthropomorphism, I think, is anthropocentrism, in which we assume that we are the only creatures that think, feel and know. And also, the unwise assumption that the way in which animals think, feel and know, is exactly the same as us. For example, chickens don't do this, but other birds feed each other by essentially throwing up into their mouths. That's a sign of great affection. That would not work for me with my husband, okay? So, you know, we would totally miss what was going on with these birds if we tried to assume that they behaved like we did. I mean, animals behave differently than we do, but I am sure that they think and feel and know. We just have to develop that beginner's mind and learn how they experience the world, rather than assume that we're the only ones who are having mental experiences or assuming that our kind of mental experiences are the only ones that matter.

Sy Montgomery is a naturalist, adventurer, and author of more than thirty acclaimed books of nonfiction for adults and children. (Photo: Vicki Steifel)

CURWOOD: Sy, in your view, what is it you think that chickens can teach us? What things can they teach us?

MONTGOMERY: Well, first of all, humility, because we misjudge them. They can teach us that all creatures have something to show, some magic to share, and that we need to be patient and pay attention to this world. Even a chicken can fill you with awe. And I think that sense of awe, that sense of connection, is something that we're all very hungry for, and a humble chicken can give that to you.

CURWOOD: Sy Montgomery, thank you so much for taking the time to come by to talk about your new book, What the Chicken Knows.

MONTGOMERY: Well thanks so much, this is a blast. I always love seeing you, Steve.

CURWOOD: Bawk, bawk, bawk!

MONTGOMERY: Bawk, bawk, bawk!

Related links:

- Learn more about Sy Montgomery

- Purchase What the Chicken Knows: A New Appreciation of the World’s Most Familiar Bird (Affiliate link supports LOE and indie bookstores)

- Check out our interview with Sy: Of Time and Turtles

- Check out our interview with Sy: The Hawk’s Way

[MUSIC: James Brown, “The Chicken – Instrumental” on The Popcorn, Universal Records]

CURWOOD: Interested in gaining hands-on experience with producing a radio show and podcast? Apply to be a Living on Earth intern this spring! The deadline is November 20th. To learn more, go to loe.org and click on the About Us tab at the top of the page. That’s L-O-E dot O-R-G.

[MUSIC: James Brown, “The Chicken – Instrumental” on The Popcorn, Universal Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Josh Croom, Daniela Faria, Mehek Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, and El Wilson.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks to NHPR, New Hampshire Public Radio. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth