Biodiversity Talks Unfinished

Air Date: Week of November 8, 2024

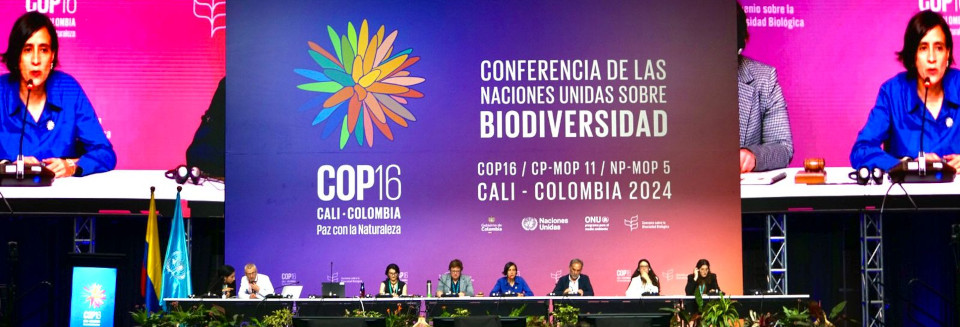

Susana Muhamad, the Colombian Minister of Environment and Sustainable Development, was the president of the 16th Conference of the Parties of the Biodiversity Convention (COP16). (Photo: UN Biodiversity, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

The latest summit for the UN’s biodiversity treaty to attempt to avert mass extinctions was recessed when it ran out of time to make major decisions. Vox journalist Benji Jones was at the meeting in Cali, Colombia and joins Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill to talk about what it did achieve and what is still unresolved.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

According to the World Wildlife Fund, the populations of vertebrate animals around the globe have plunged by three-quarters since 1970. The growing concern about biodiversity declines led to a landmark United Nations treaty in 1993 called the Convention on Biological Diversity. The latest talks for this treaty just halted at COP16 in Cali, Colombia, when attendance fell below a quorum as negotiators ran out of time, and many had to catch flights home. Key decisions have been postponed until an interim meeting set for next year in Bangkok. Benji Jones is an environmental journalist who covers biodiversity loss and climate change for Vox, and he went to Cali. He joined Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill to talk about what COP16 did achieve and what it left unresolved.

JONES: Yes. So, I just got back. It was incredible, in a sense, like it brought together leaders from pretty much every single country on the planet. When you think about what was the goal of this big conference, COP 16, it was really about checking in on progress: how much have things changed since the last conference in 2022 so lots of conversation about how we're not on track, the world is not on track. And then there were a couple other important kind of agenda items for this conference. One thing was trying to figure out the finance piece. So, when you think about what it takes to stop the biodiversity crisis, to prevent further extinctions, it's really expensive. So, the amount of money that's needed, in addition to what we're already spending, is about $700 billion so a big part of this conference in Cali Colombia was, how do we come up with that much money? There were also lots of conversations about, how do we make indigenous people and local communities more a part of these solutions? How do we have them have more influence in these spaces, just given that indigenous people in local communities are known for being some of the best conservation folks on the planet, and they've been doing it for a long, long time. And the third thing that caught my attention was a debate around something slightly obscure called Digital sequence information, and it is essentially about, how do we get companies who are developing drugs and other products using the DNA of wild animals or plants. How do we get those companies to pay for conservation?

O'NEILL: So, it's about getting something like, maybe, like a Moderna or a Pfizer to sort of pony up some money for biodiversity?

From left to right Brazil Foreign minister Leonardo Cleaver de Athayde, Eve Bazaiba Masudi Vice Prime minister and Environment Minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo (center), Daniel Thmpang Sumurung Simajuntak of Indonesia (right) raising arms at COP15 of the UN Biodiversity treaty in 2022 in Montreal. (Photo: UN Biodiversity, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

JONES: Yeah, it's a really interesting topic. We have been developing all kinds of drugs for many years now, using things that are found from nature. You think of things like aspirin, I think that comes from a kind of bark, even like the enzyme used to stonewash jeans, comes from microbes. So, tons of things that we rely on come from… From plants and animals, things found in nature. What this topic is referring to though, is actually not the physical plants and animals that we use to develop drugs, but the DNA, the genetic sequences of those plants and animals that gets uploaded to databases that companies will then use. So, you have to kind of think about the fact that today, when a company, yes, like Pfizer, like Moderna, is going to make products like a vaccine, they actually rely on databases that store genetic information in order to make these products. And so basically, genetic information, literally, like DNA and RNA sequences, are very valuable for commercial interests and this conversation at COP 16 was about, how do we get those companies that are benefiting from that information, they're making money, they're creating products that have a lot of value, that could save lives, in the case of vaccines, how do we get those companies to pay for conservation, and especially conservation in countries that harbor a lot of the biodiversity from which those genetic sequences come.

O'NEILL: And so, I mean, ultimately, what was decided at COP 16 about this topic?

JONES: So basically, leaders from around the world, they decided to create a mechanism whereby companies in sectors of the economy that rely heavily on genetic sequences for their products, so things like pharmaceuticals, food companies, plant breeding organizations and so forth. Under this new plan, those companies should contribute a portion of their profits or revenue into a fund called the Cali Fund, and that fund will go towards conservation.

O'NEILL: What have you seen from the pharmaceutical industry, sort of generally in response to this Cali Fund?

JONES: Yeah. So, I would say there's a mixed response. I've talked to companies who see themselves as leaders when it comes to biodiversity and conservation, and they're willing to contribute. And then there's the flip side, which is other companies that are very much frustrated with this new restriction, and you've already seen some organizations, including an association of pharmaceutical companies, push back and say that this is potentially going to harm corporate interests and is too restrictive and could potentially stymie innovation. So, I think what's really key here is that you'll have some companies play ball, and other companies are not going to and hopefully you'll get enough contributions to this fund that it will actually start channeling money into conservation.

Secretary-General António Guterres (center) poses for a photo with Regional Group Two - Asia Pacific, during the fifteenth meeting of the Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15) in Montreal in December 2022. (Photo: UN Biodiversity, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: Now the United States actually is not a member of the Convention on Biological Diversity. So, what does this decision mean for, you know, a US based pharmaceutical company? I know it's sort of on good faith, generally speaking but is there sort of any implication for a US based company?

JONES: Yeah so, you're totally right. The US is notably on the sidelines at these big meetings under this convention, which, by the way, is the most important biodiversity meeting on the planet. And the US is one of only two nations that are not members of this treaty. The other one is the Holy See, aka Vatican City, which is, of course, very, very tiny. So, the US is really effectively the only country that is not part of this agreement. And yeah, the US is the largest economy in the world. We are home to some of the biggest pharmaceutical companies, not to mention other companies that are in sectors that rely heavily on this digital biodiversity, data, the genetic sequences and so on. And so, it very much is a good question about, okay, if the US is not playing ball, or if the US is not part of this agreement, can we really expect the companies in the US to contribute to this new fund? And I think it's sort of unclear right now what will end up happening, but I've talked to a number of experts on this stuff, and they basically told me that a lot of the multinational companies in the US, so the biggest pharmaceutical companies, they probably are going to contribute, or at least they're going to think about the implications if they don't, which could be a reputational risk. So, I think a lot of the largest pharmaceutical companies that operate all across the world are gonna have more pressure to contribute, because if they wanna operate in other countries, including like the EU or Brazil or wherever those other parts of the world are members of this treaty. And so, they will likely feel pressure to contribute if they want to continue to operate on this kind of international scale. And so, I think that is like the mechanism by which the US based companies, especially the multinational ones, are more likely to contribute, but it's definitely an open question still.

O'NEILL: So, I mean, not to have you play mind reader here, but Benji, why is it that the US is not a party to this treaty?

JONES: The simple answer is that the US does not like treaties in general, no matter what the topic is, and that's because the US, and especially conservative lawmakers in the US tend to be wary of any kinds of treaties that might restrict what they see as American sovereignty. So, there's this idea that is espoused by some conservative lawmakers that if the US were to join a treaty like this, they would have to do something that businesses wouldn't like. So, for example, there's concern that companies that operate in the pharmaceutical space might have to share their intellectual property, or they might have additional environmental regulations placed on them. So, there are concerns about restrictions across the board, should the US join a treaty like this? What I understand based on lots of interviews with experts in international affairs, is that those concerns are mostly unfounded, but it remains to be an obstacle to getting the US to join any treaty. And I should just say no president since Bill Clinton in the 90s has introduced the Convention on Biological Diversity to the Senate to be ratified because they just don't believe that it has the votes. It requires a two thirds majority vote in the Senate to ratify any treaty.

O'NEILL: So, you said a little bit about the presence of indigenous communities at this convention. What was going on there?

Canadian artist Benjamin Von Wong built a six-meter art piece with showcasing different ecosystems, from tropical jungles to kelp forests with the help of 200 students. It was on display at COP 16 of the UN Biodiversity treaty in Cali, Colombia. (Photo: Von Wong Productions 2024, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

JONES: This was a really cool part of this COP. So, it took place in Cali Colombia, and it was kind of known among the leaders of this convention that it was the "COP de la gente, or COP of the people". And so, people were really a major focus of this meeting. And that hasn't always been the case, certainly at other COPs, and not even in the kind of history of conservation. Usually it's kind of wildlife first, and then people second, and now there's this understanding that people are actually essential to doing conservation. You can't protect the environment without also protecting people who help safeguard it. At this COP, there were more indigenous people at this event, I believe, than any other COP in history. So that was significant in itself, and also one of the major outcomes of this meeting was that world leaders, again, these officials from nearly every country agreed on creating a permanent body for indigenous people in the Convention on Biological Diversity. And essentially what that means is that going forward, indigenous people and local communities have much more say about the outcomes of these conventions. And again, this convention is about protecting life on Earth, and so having indigenous people who are all around the planet, who have a long history of safeguarding life on earth, having them more central, more influential in these discussions, is absolutely key. And it especially is key thinking about a history of conservation where indigenous people in local communities have been excluded from these conservation spaces and often kicked off their land to do conservation. So, I think this is a turning point for the movement to save nature.

O'NEILL: And now we've been talking about, you know, these wins that we were getting out of COP 16, but what sort of missed opportunities or lack of progress were you seeing there?

JONES: Yeah, it's a good question. So, I think one of them is, again, coming back to money. There just is not enough money flowing. There were commitments at this COP of I believe, 163 million dollars from wealthy nations for conservation, especially in developing countries, 163 million dollars is really not where it needs to be in terms of closing the 700 billion dollar gap in funding. So funding is a really big one. And the other thing to mention is that this COP just did not finish. So, at this event, countries were supposed to agree on a way to measure progress towards all these goals under the 2022 COP. And so, the finance piece and this measuring piece were not agreed on. And so, COP literally kind of ran out of time and actually, what ultimately happened was that on the last day, it ran so late, it went through the entire night the negotiations that people started peeling off, taking flights to go back home, and there was not a quorum. There weren't enough countries present to even continue making decisions; to continue negotiating and so they had to cut the entire COP short. And that means that there is not going to be an agreement around this strategy for raising money or the strategy for measuring progress for several months. So, there was a lot that just didn't get finished. And I think that is like a bit frustrating for people who are involved in this process, especially after spending two weeks in Cali negotiating.

COP16 ran out of time, closing plenary sessions ran out of time and several pledges had to be postponed. One important decision that wasn’t made was on how biodiversity targets should be measured. (Photo: UN Biodiversity, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: I saw a quote from a negotiator from Fiji who said that she was the only one left in her delegation and the only remaining Pacific Island country, because those nations didn't have the funds to be changing their flights to stick around any longer.

JONES: Yeah, totally and that underscores a broader problem at these conventions, which is that you have a divide between very wealthy countries and the global north, meaning north of the equator, typically, and the global south, where you have more of the developing countries. And that tension is always present at these international events.

O'NEILL: So Benji, from your perspective, how are we doing in terms of making progress on global conservation?

JONES: So, I think on the one hand it's easy to get depressed in the numbers showing extinction rates, showing deforestation, all of which is trending in the wrong direction. But then the flip side is that we have these venues to bring leaders from around the world together, and I'm talking about government officials, so people in the environmental ministries from every country, leaders in the nonprofit space, top scientists, companies, everyone together in this space to try to come together and solve this problem, to figure out a way forward where we can preserve biodiversity, the healthy functioning of ecosystems. And I think there's a lot to be hopeful for in these spaces, because everyone is together and trying to work on this collectively, and that is ultimately what it will take to solve these problems. So, I think, yes, while things are not looking good today, there's the will to plot a different future, and to me, that is pretty significant, and personally gives me hope in what it is otherwise like a very depressing beat to work on. There's a lot of excitement and energy in these rooms, in these spaces, that I do think has the potential to translate to action.

CURWOOD: That’s Vox correspondent Benji Jones speaking with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill. Multiple decisions from COP16 won't be officially adopted until the interim meeting set for 2025 in Bangkok. The next full Conference of the Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity, COP17, will be held in Armenia in 2026.

Links

VOX | “A groundbreaking new plan to get Big Pharma to pay for wildlife conservation”

VOX | “Every country is negotiating a plan to save nature. Except the US.”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth