November 8, 2024

Air Date: November 8, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Climate and Trump's Re-Election

/ Vernon Loeb & Marianne LavelleView the page for this story

The re-election of Donald Trump casts US climate action into doubt. President-elect Trump has vowed he will again pull the US out of the Paris Climate Agreement, cancel President Biden’s climate policies and unleash American fossil fuels. Inside Climate News Executive Editor Vernon Loeb and Reporter Marianne Lavelle join Hosts Steve Curwood and Jenni Doering for a roundtable discussion about what’s next for the climate, environmental policy and journalism. (14:35)

Biodiversity Talks Unfinished

/ Benji JonesView the page for this story

The latest summit for the UN’s biodiversity treaty to attempt to avert mass extinctions was recessed when it ran out of time to make major decisions. Vox journalist Benji Jones was at the meeting in Cali, Colombia and joins Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill to talk about what it did achieve and what is still unresolved. (14:46)

Coke and Pepsi Face Plastic Lawsuit

View the page for this story

The County of Los Angeles is suing beverage giants Coca-Cola and PepsiCo over alleged deceptive marketing around plastics recycling. Coke and Pepsi as well as other brands they own including Mountain Dew, Sprite, Gatorade, and Smartwater are often packaged in single-use plastic bottles, which are not infinitely recyclable despite what many consumers allegedly have been led to believe. (02:01)

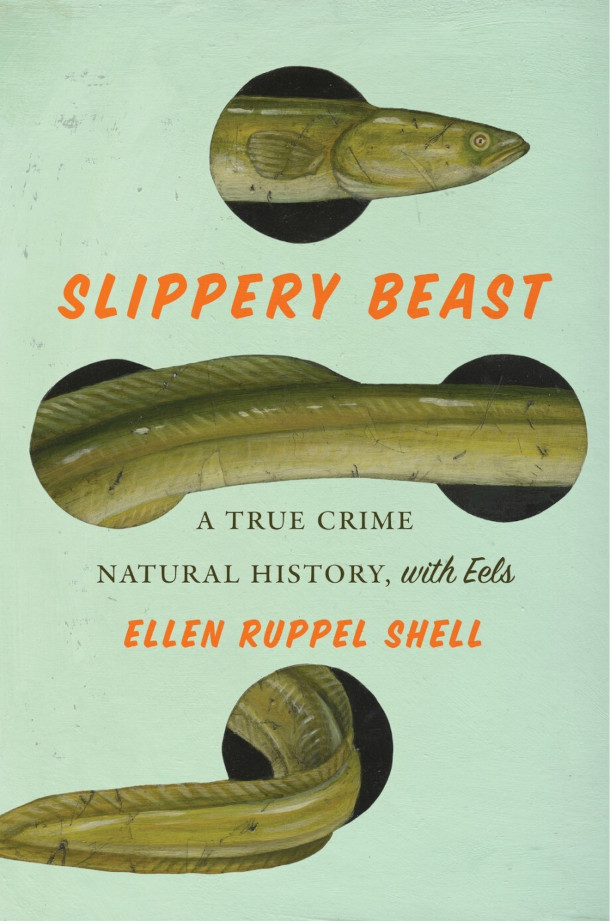

Slippery Beast: A True Crime Natural History, with Eels

View the page for this story

Eels play an important ecological role in many rivers and streams, but they’re so eel-usive that even eel scientists have been challenged to observe them mating in the wild. Ellen Ruppel Shell is author of the 2024 book Slippery Beast: A True Crime Natural History, with Eels, and she sheds light on the eel’s murky ecology and path through the seafood industry. (14:28)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

241108 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Benji Jones, Ellen Ruppel Shell

REPORTERS: Marianne Lavelle, Vernon Loeb

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The path forward for environmental policy and journalism now that Donald Trump has won another Presidential term vowing to drill, baby, drill.

LOEB: For the rest of our lives, every other story is going to play out on the stage of climate and if anything, the re-election of Donald Trump sort of accentuates that fact.

CURWOOD: Plus, why eels are giving some Mainers cold feet about fishing.

SHELL: He said, no, no, I’m not talking about eels big enough to bite me. I’m talking about those baby eels. Ever since the price on those things went through the roof, it’s gotten dangerous down by the river. This year, this season, they’re going for about $2500 a pound.

CURWOOD: Also, mixed results at the biodiversity summit. That and more this week on Living on Earth—stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Climate and Trump's Re-Election

President-elect Donald Trump. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I'm Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And we're here now to talk about what it means for the environment now that Donald Trump has won a second term in the White House.

DOERING: Yes, and with Republican control of the Senate as well, Steve.

CURWOOD: And we're joined now by our media partners from Inside Climate News. That's Vernon Loeb, he's Executive Editor, and Marianne Lavelle, who is the Washington bureau chief for them. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Marianne and Vernon.

LAVELLE: Thanks for having us.

LOEB: Thanks a lot. Great to be here.

CURWOOD: So, what's your view of how the world is gonna look at us that we have chosen a leader who denies climate change when we've been seeing temperatures going up and storms and such are getting worse and worse?

LOEB: Well, I think the world has seen this before. When Trump was in office the first time, one of the first things he did was take the country out of the Paris Agreement. Clearly, the world is expecting he'll do that again. Climate action didn't stop when he did that the first time. It won't stop this time. But I think clearly, world leaders feel like progress on climate is going to be a lot harder to achieve with Trump in office and with the US out of the official agreement. It's not a good moment for climate. Again, I don't think progress is going to grind to a halt, but it's not a good moment.

LAVELLE: Well, next week, climate negotiations begin in Azerbaijan and US negotiators, the Biden administration's negotiators, were going to go there and argue that more nations should be giving to the fund to address loss and damages in these developing countries that did so little to cause the climate crisis, but they are feeling the brunt of the climate crisis. It is going to be very hard for the US negotiators to have leverage or credibility when everyone there knows that policy is going to change completely on January 21 of next year. So, it just makes our role as a leader on these issues much smaller going forward as the rest of the world continues to grapple with climate change.

With Donald Trump expected to pull the US out of the Paris Climate Agreement again, the country is likely to lose credibility in the upcoming COP29 negotiations in Azerbaijan. (Photo: International Transportation Forum, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: So, President Biden was able to pass some pretty significant climate legislation with the Inflation Reduction Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. But to what extent will Trump potentially roll back some of that legislation, given what he said about these laws?

LAVELLE: Well, President-elect Trump has made clear that he is going to roll back the regulations that are meant to get the auto industry to nudge it toward electric vehicles over the next decade. He says he is going to repeal that on day one, and that is going to make a big difference. My colleague and I have been working all year on writing about the politics of electric vehicles, and one of the analysts we've talked to says that there is going to be 40% less demand for EV batteries and EV technology under a Trump administration than there would have been under a Harris administration. So those kinds of changes in policy are bound to make a huge difference in how quickly we make the transition that's already going on all over the world to electric vehicles.

CURWOOD: Vernon, your reporter Bob Berwyn said on our air recently that if the US falls behind on developing electric vehicles, it'll be like we're a rusting locomotive on a sidetrack while the rest of the world, i.e. China and many others, proceed in this area. What are the risks and possibilities there? What are we up against if incoming President Trump does succeed in pushing back on progress for electric vehicles?

LOEB: Well, I think clearly, we'll fall even farther behind on EVs than we are already. China is starting to show world dominance on EVs. They're selling Chinese EVs in Mexico right now. And but for the Trump tariffs on Chinese EVs, they'd undoubtedly be flooding our market as well. So, with the Trump tariffs, which he's given every indication it is going to continue, we're not going to see Chinese EVs coming into our country, but what we're going to see is Chinese EVs all over the world, and we will fall farther and farther behind the Chinese and the electric vehicle market, as we're already behind them in the battery market and the solar market.

Donald Trump has indicated that he will repeal regulations that encourage EV production. (Photo: Ivan Radic, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: I want to ask about Project 2025, which President-elect Trump has attempted to distance himself from, but it's broadly seen as a playbook of what might happen in terms of cuts at EPA, NOAA, Department of the Interior, when Trump comes back into the White House. So, what's your perspective, Marianne, on what might happen to agencies like EPA?

LAVELLE: I think the important thing to watch is who the President-elect appoints to these key agencies. In many cases, it may well be that some of the authors of Project 2025 are going to be top of the list to really take over those agencies, and that's because all of these folks who wrote Project 2025, they worked in the Trump administration, they know the agencies really deeply, and they know what programs they want to cut and that is very in line with what Trump has said he wants to do. He wants massive cutbacks in the agencies. And as much as he has tried to distance himself from Project 2025, they're right in line on what they see, which is a smaller role for the federal government, and that includes the environmental and science agencies.

LOEB: There's a long description in Project 2025, about how the EPA's enforcement capability should be pulled way back. And instead, the agency should move to something called compliance assistance, which is working more closely with corporations. The 2025 also talks about dismantling NOAA, which is the National Weather Service. It's the agency that tracks hurricanes and National Hurricane Center. Project 2025 even calls for the repeal of the EPA efficiency ratings for appliances, the ENERGY STAR efficiency ratings. So, Project 2025 could be a real disaster for environmental protection, if it is indeed the Trump blueprint.

Donald Trump will likely roll back environmental regulations yet again, following the record of his first administration. (Photo: Michael Levine-Clark, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND)

CURWOOD: I guess we're about to find out, huh? What do you see coming up in terms of environmental justice now? The Biden administration set up a White House Advisory Council on Environmental Justice and wanted to set aside 40% of certain funds for environmental justice communities. What might we expect under the next Trump administration?

LAVELLE: It's interesting. One of the things Project 2025 says to do is to eliminate EPA's Office of Environmental Justice. It definitely is in the sights of the team that is around Trump to really redirect this initiative to address environmental justice. One thing I noticed is that House Republicans this week put out a report on environmental justice grants by the Biden administration, and they're very critical of those grants because they're going to groups that, for example, oppose the natural gas export terminals on the Gulf Coast. What this report does is kind of gives a blueprint for the incoming Trump administration on what grants to withdraw, and also kind of a basis for withdrawing the program altogether. So, I think that that report came out very much with an awareness that Trump is coming into the White House with an eye to cutting back the support for these communities that are overburdened with pollution and have been for a long time.

DOERING: Marianne, you mentioned natural gas exports. So, Vernon, I want to ask you, what do you think is going to happen now that the Trump administration is coming back in and has 20 something projects which it can potentially give the green light to?

The power of federal agencies like the EPA and NOAA is expected to be curbed under a second Trump administration. (Photo: TexasGOPVote.com, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

LOEB: Yeah, the Biden administration put a hold on those projects as it considered the climate implications of them. And my hunch is that that will be one of the first things Trump does away with and basically gives those plants the green light as part of his, you know, energy dominance, "drill, baby, drill" approach. Of all the industries, none has fared better under Trump than the fossil fuel industry. So, I would expect a real explosion of LNG exports over the next four years under Trump too.

DOERING: And just remind us, why are climate activists so concerned about those terminals?

LOEB: You know, the terminals just lead to more fracking. We're already the leading oil and gas nation in the world, and if we can continue to frack and start exporting our natural gas as liquefied natural gas to Europe, which is still somewhat smarting from the loss of Russian natural gas, it just means more fracking. And when you've got more fracking, you've got more air pollution, more greenhouse gas emissions, more produced water piling up with no place to dispose of it. LNG exports means more fracking across the nation.

CURWOOD: And Vernon, I’ve seen some research that says that the actual climate footprint, carbon footprint, of exported natural gas can even exceed that of burning coal.

DOERING: So how do you both feel about this outcome? Marianne, and let's start with you, Vernon?

LOEB: I tend to look at climate change as a matter of fact in science and not as a partisan issue. And so, through that lens, I don't think the outcome is good here at all. We have a President-elect who's said that the first thing he's going to do is remove the nation from the Paris Agreement. Once again, that can't be good for the climate picture. Climate change comes down to cutting the emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gasses, and we haven't, as a global community, succeeded in doing that since the Paris Accord was negotiated in 2015. There's more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere now than any other point in human history. The planet is warming faster now than in any other point in human history. We have a President now coming in who says climate change is something of a hoax, and I'm not even going to be part of the global process to deal with it. I just don't see that as a good outcome.

President-elect Donald Trump has expressed support for natural gas and other fossil fuels. (Photo: Trudy E. Bell, Courtesy of FracTracker Alliance, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

LAVELLE: As somebody who's been writing about this for a long time, you know, I usually focus on the stories I'm telling and what I'm working on, not looking out at the big picture that much. This forces you to look at the big picture. And anyone who has, you know, young people in their lives, you think, you know, what kind of world are we leaving for them? And the way I deal with it is just kind of focus on the importance of the work we're doing, trying to explain the science, as Vernon said, and tell people really that there are things that can be done to address climate change, and we know what they are, and it's going to take all of us to do something about it.

CURWOOD: So, as we wrap up here, talk to me about what some people call the glimmer of hope, the states and localities. Vernon, can you start us on that?

LOEB: Yeah, so voters in Washington firmly rejected a measure on the ballot that would have overturned the state's signature climate law. In California, the voters approved a 10-billion-dollar bond fund to fund projects that that focus on resiliency and coastal adaptation and response to floods and wildfires. And similarly, in Honolulu, voters also approved a climate resiliency fund there. So, kind of a mixed result, right? While the national vote was going for Trump, who's someone who's sort of avowedly almost a climate denier, you've got majorities in these states clearly voting for climate change measures to fund things like adaptation and resiliency.

LAVELLE: And states always have been at the forefront of setting goals on clean energy that have been very effective over the years, and I am sure that environmental activists are going to be focusing on getting those goals strengthened and just continuing to go forward in the transition to renewable energy and policy at the states to make that happen.

CURWOOD: Well, you know, the founders of the United States did give states rights, and here's an interesting case where they will be employed.

DOERING: So, I think I hear both of you saying, you know, even with journalism at sort of this perilous time, you're not backing down, and you're going to follow these stories.

States and cities still showed support for climate legislation in the 2024 election. For example, voters in Honolulu approved a climate resiliency fund. (Photo: John Fowler, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

LOEB: You know, look, I think journalism is one of the most powerful civic forces in America. You know, without journalists, how would people know? So no, we're not backing down. If anything, I think our work is more essential than ever right now to tell the story of what I think is the most you know important story on the planet, which is climate change. For the rest of our lives, every other story is gonna play out on the stage of climate. And if anything, the reelection of Donald Trump sort of accentuates that fact.

CURWOOD: Jenni, we could just go on here, but I see that we're out of time. Let me thank Vernon Loeb, the Executive Editor of Inside Climate News.

LOEB: Great to be here. Thanks so much for having me.

DOERING: And thank you so much, Marianne Lavelle, reporter for Inside Climate News.

LAVELLE: Thanks so much, good to be here with you.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “Trump’s Win Casts Shadow over US Progress, Global Leadership”

- Inside Climate News | “After Trump Win, World Says, ‘We’ve Been Here Before’”

- Inside Climate News | “Climate Initiatives Fare Well Across the Country Despite National Political Climate"

[MUSIC: Joe Pass, “Chloe” on Intercontinental, Edel Germany GmbH]

DOERING: Just ahead, the latest global biodiversity talks run out of time to make major decisions. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joe Pass, “Chloe” on Intercontinental, Edel Germany GmbH]

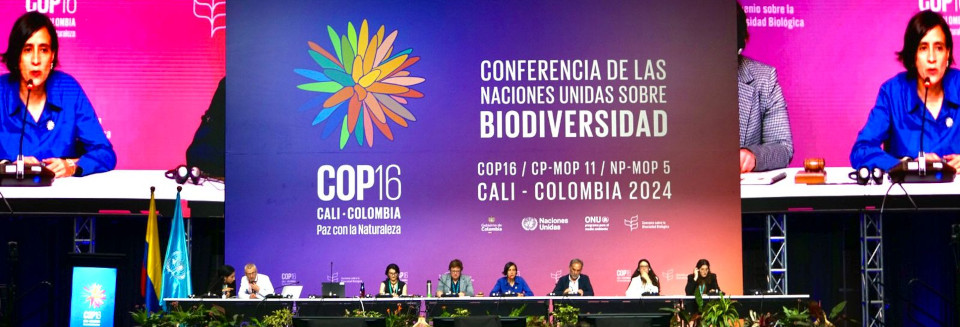

Biodiversity Talks Unfinished

Susana Muhamad, the Colombian Minister of Environment and Sustainable Development, was the president of the 16th Conference of the Parties of the Biodiversity Convention (COP16). (Photo: UN Biodiversity, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

According to the World Wildlife Fund, the populations of vertebrate animals around the globe have plunged by three-quarters since 1970. The growing concern about biodiversity declines led to a landmark United Nations treaty in 1993 called the Convention on Biological Diversity. The latest talks for this treaty just halted at COP16 in Cali, Colombia, when attendance fell below a quorum as negotiators ran out of time, and many had to catch flights home. Key decisions have been postponed until an interim meeting set for next year in Bangkok. Benji Jones is an environmental journalist who covers biodiversity loss and climate change for Vox, and he went to Cali. He joined Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill to talk about what COP16 did achieve and what it left unresolved.

JONES: Yes. So, I just got back. It was incredible, in a sense, like it brought together leaders from pretty much every single country on the planet. When you think about what was the goal of this big conference, COP 16, it was really about checking in on progress: how much have things changed since the last conference in 2022 so lots of conversation about how we're not on track, the world is not on track. And then there were a couple other important kind of agenda items for this conference. One thing was trying to figure out the finance piece. So, when you think about what it takes to stop the biodiversity crisis, to prevent further extinctions, it's really expensive. So, the amount of money that's needed, in addition to what we're already spending, is about $700 billion so a big part of this conference in Cali Colombia was, how do we come up with that much money? There were also lots of conversations about, how do we make indigenous people and local communities more a part of these solutions? How do we have them have more influence in these spaces, just given that indigenous people in local communities are known for being some of the best conservation folks on the planet, and they've been doing it for a long, long time. And the third thing that caught my attention was a debate around something slightly obscure called Digital sequence information, and it is essentially about, how do we get companies who are developing drugs and other products using the DNA of wild animals or plants. How do we get those companies to pay for conservation?

O'NEILL: So, it's about getting something like, maybe, like a Moderna or a Pfizer to sort of pony up some money for biodiversity?

From left to right Brazil Foreign minister Leonardo Cleaver de Athayde, Eve Bazaiba Masudi Vice Prime minister and Environment Minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo (center), Daniel Thmpang Sumurung Simajuntak of Indonesia (right) raising arms at COP15 of the UN Biodiversity treaty in 2022 in Montreal. (Photo: UN Biodiversity, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

JONES: Yeah, it's a really interesting topic. We have been developing all kinds of drugs for many years now, using things that are found from nature. You think of things like aspirin, I think that comes from a kind of bark, even like the enzyme used to stonewash jeans, comes from microbes. So, tons of things that we rely on come from… From plants and animals, things found in nature. What this topic is referring to though, is actually not the physical plants and animals that we use to develop drugs, but the DNA, the genetic sequences of those plants and animals that gets uploaded to databases that companies will then use. So, you have to kind of think about the fact that today, when a company, yes, like Pfizer, like Moderna, is going to make products like a vaccine, they actually rely on databases that store genetic information in order to make these products. And so basically, genetic information, literally, like DNA and RNA sequences, are very valuable for commercial interests and this conversation at COP 16 was about, how do we get those companies that are benefiting from that information, they're making money, they're creating products that have a lot of value, that could save lives, in the case of vaccines, how do we get those companies to pay for conservation, and especially conservation in countries that harbor a lot of the biodiversity from which those genetic sequences come.

O'NEILL: And so, I mean, ultimately, what was decided at COP 16 about this topic?

JONES: So basically, leaders from around the world, they decided to create a mechanism whereby companies in sectors of the economy that rely heavily on genetic sequences for their products, so things like pharmaceuticals, food companies, plant breeding organizations and so forth. Under this new plan, those companies should contribute a portion of their profits or revenue into a fund called the Cali Fund, and that fund will go towards conservation.

O'NEILL: What have you seen from the pharmaceutical industry, sort of generally in response to this Cali Fund?

JONES: Yeah. So, I would say there's a mixed response. I've talked to companies who see themselves as leaders when it comes to biodiversity and conservation, and they're willing to contribute. And then there's the flip side, which is other companies that are very much frustrated with this new restriction, and you've already seen some organizations, including an association of pharmaceutical companies, push back and say that this is potentially going to harm corporate interests and is too restrictive and could potentially stymie innovation. So, I think what's really key here is that you'll have some companies play ball, and other companies are not going to and hopefully you'll get enough contributions to this fund that it will actually start channeling money into conservation.

Secretary-General António Guterres (center) poses for a photo with Regional Group Two - Asia Pacific, during the fifteenth meeting of the Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP15) in Montreal in December 2022. (Photo: UN Biodiversity, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: Now the United States actually is not a member of the Convention on Biological Diversity. So, what does this decision mean for, you know, a US based pharmaceutical company? I know it's sort of on good faith, generally speaking but is there sort of any implication for a US based company?

JONES: Yeah so, you're totally right. The US is notably on the sidelines at these big meetings under this convention, which, by the way, is the most important biodiversity meeting on the planet. And the US is one of only two nations that are not members of this treaty. The other one is the Holy See, aka Vatican City, which is, of course, very, very tiny. So, the US is really effectively the only country that is not part of this agreement. And yeah, the US is the largest economy in the world. We are home to some of the biggest pharmaceutical companies, not to mention other companies that are in sectors that rely heavily on this digital biodiversity, data, the genetic sequences and so on. And so, it very much is a good question about, okay, if the US is not playing ball, or if the US is not part of this agreement, can we really expect the companies in the US to contribute to this new fund? And I think it's sort of unclear right now what will end up happening, but I've talked to a number of experts on this stuff, and they basically told me that a lot of the multinational companies in the US, so the biggest pharmaceutical companies, they probably are going to contribute, or at least they're going to think about the implications if they don't, which could be a reputational risk. So, I think a lot of the largest pharmaceutical companies that operate all across the world are gonna have more pressure to contribute, because if they wanna operate in other countries, including like the EU or Brazil or wherever those other parts of the world are members of this treaty. And so, they will likely feel pressure to contribute if they want to continue to operate on this kind of international scale. And so, I think that is like the mechanism by which the US based companies, especially the multinational ones, are more likely to contribute, but it's definitely an open question still.

O'NEILL: So, I mean, not to have you play mind reader here, but Benji, why is it that the US is not a party to this treaty?

JONES: The simple answer is that the US does not like treaties in general, no matter what the topic is, and that's because the US, and especially conservative lawmakers in the US tend to be wary of any kinds of treaties that might restrict what they see as American sovereignty. So, there's this idea that is espoused by some conservative lawmakers that if the US were to join a treaty like this, they would have to do something that businesses wouldn't like. So, for example, there's concern that companies that operate in the pharmaceutical space might have to share their intellectual property, or they might have additional environmental regulations placed on them. So, there are concerns about restrictions across the board, should the US join a treaty like this? What I understand based on lots of interviews with experts in international affairs, is that those concerns are mostly unfounded, but it remains to be an obstacle to getting the US to join any treaty. And I should just say no president since Bill Clinton in the 90s has introduced the Convention on Biological Diversity to the Senate to be ratified because they just don't believe that it has the votes. It requires a two thirds majority vote in the Senate to ratify any treaty.

O'NEILL: So, you said a little bit about the presence of indigenous communities at this convention. What was going on there?

Canadian artist Benjamin Von Wong built a six-meter art piece with showcasing different ecosystems, from tropical jungles to kelp forests with the help of 200 students. It was on display at COP 16 of the UN Biodiversity treaty in Cali, Colombia. (Photo: Von Wong Productions 2024, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

JONES: This was a really cool part of this COP. So, it took place in Cali Colombia, and it was kind of known among the leaders of this convention that it was the "COP de la gente, or COP of the people". And so, people were really a major focus of this meeting. And that hasn't always been the case, certainly at other COPs, and not even in the kind of history of conservation. Usually it's kind of wildlife first, and then people second, and now there's this understanding that people are actually essential to doing conservation. You can't protect the environment without also protecting people who help safeguard it. At this COP, there were more indigenous people at this event, I believe, than any other COP in history. So that was significant in itself, and also one of the major outcomes of this meeting was that world leaders, again, these officials from nearly every country agreed on creating a permanent body for indigenous people in the Convention on Biological Diversity. And essentially what that means is that going forward, indigenous people and local communities have much more say about the outcomes of these conventions. And again, this convention is about protecting life on Earth, and so having indigenous people who are all around the planet, who have a long history of safeguarding life on earth, having them more central, more influential in these discussions, is absolutely key. And it especially is key thinking about a history of conservation where indigenous people in local communities have been excluded from these conservation spaces and often kicked off their land to do conservation. So, I think this is a turning point for the movement to save nature.

O'NEILL: And now we've been talking about, you know, these wins that we were getting out of COP 16, but what sort of missed opportunities or lack of progress were you seeing there?

JONES: Yeah, it's a good question. So, I think one of them is, again, coming back to money. There just is not enough money flowing. There were commitments at this COP of I believe, 163 million dollars from wealthy nations for conservation, especially in developing countries, 163 million dollars is really not where it needs to be in terms of closing the 700 billion dollar gap in funding. So funding is a really big one. And the other thing to mention is that this COP just did not finish. So, at this event, countries were supposed to agree on a way to measure progress towards all these goals under the 2022 COP. And so, the finance piece and this measuring piece were not agreed on. And so, COP literally kind of ran out of time and actually, what ultimately happened was that on the last day, it ran so late, it went through the entire night the negotiations that people started peeling off, taking flights to go back home, and there was not a quorum. There weren't enough countries present to even continue making decisions; to continue negotiating and so they had to cut the entire COP short. And that means that there is not going to be an agreement around this strategy for raising money or the strategy for measuring progress for several months. So, there was a lot that just didn't get finished. And I think that is like a bit frustrating for people who are involved in this process, especially after spending two weeks in Cali negotiating.

COP16 ran out of time, closing plenary sessions ran out of time and several pledges had to be postponed. One important decision that wasn’t made was on how biodiversity targets should be measured. (Photo: UN Biodiversity, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: I saw a quote from a negotiator from Fiji who said that she was the only one left in her delegation and the only remaining Pacific Island country, because those nations didn't have the funds to be changing their flights to stick around any longer.

JONES: Yeah, totally and that underscores a broader problem at these conventions, which is that you have a divide between very wealthy countries and the global north, meaning north of the equator, typically, and the global south, where you have more of the developing countries. And that tension is always present at these international events.

O'NEILL: So Benji, from your perspective, how are we doing in terms of making progress on global conservation?

JONES: So, I think on the one hand it's easy to get depressed in the numbers showing extinction rates, showing deforestation, all of which is trending in the wrong direction. But then the flip side is that we have these venues to bring leaders from around the world together, and I'm talking about government officials, so people in the environmental ministries from every country, leaders in the nonprofit space, top scientists, companies, everyone together in this space to try to come together and solve this problem, to figure out a way forward where we can preserve biodiversity, the healthy functioning of ecosystems. And I think there's a lot to be hopeful for in these spaces, because everyone is together and trying to work on this collectively, and that is ultimately what it will take to solve these problems. So, I think, yes, while things are not looking good today, there's the will to plot a different future, and to me, that is pretty significant, and personally gives me hope in what it is otherwise like a very depressing beat to work on. There's a lot of excitement and energy in these rooms, in these spaces, that I do think has the potential to translate to action.

CURWOOD: That’s Vox correspondent Benji Jones speaking with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill. Multiple decisions from COP16 won't be officially adopted until the interim meeting set for 2025 in Bangkok. The next full Conference of the Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity, COP17, will be held in Armenia in 2026.

Related links:

- VOX | “A groundbreaking new plan to get Big Pharma to pay for wildlife conservation”

- VOX | “Every country is negotiating a plan to save nature. Except the US.”

- Learn more about Benji Jones

[MUSIC: Luise Fernanda Gonzalez, “Ojo al Toro” on Columbia en Flauta (Columbia en Intrumentos), Alvaro Roa Leguizamon]

Coke and Pepsi Face Plastic Lawsuit

Both PepsiCo and the Coca-Cola Company have been sued by Los Angeles County for allegedly misleading claims about plastic recycling. (Photo: josecarlosfernandez, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

DOERING: A brief update now on attempts to rein in plastic waste. Major negotiations aimed at a treaty curtailing plastics worldwide resume later in November in Busan, South Korea. But many localities are not waiting for the international community to act. On October 30th the County of Los Angeles sued Coca-Cola and PepsiCo over plastic. These two companies dominate the carbonated beverage market with Coke and Pepsi of course, but they also sell Mountain Dew, Sprite, Gatorade, Smartwater, and more, typically in plastic containers. L.A. County alleges that PepsiCo and Coca-Cola used misleading marketing tactics to convince consumers that their plastic bottles could and would be recycled. Though California has one of the highest plastic bottle recycling rates in the country, around 70%, that still means some 3.5 billion bottles are not recycled every year in the Golden state. These end up anywhere from landfills to waterways. According to the L.A. County complaint, plastic makes up seven out of ten litter products found on California’s prized beaches. And nationwide, only about 5 or 6% of all plastic is recycled. Even the bottles that are recycled are often "downcycled," meaning that they are processed into something that can't be used again, such as plastic furniture or fuel. It’s unclear what the penalties could be if the companies lose the lawsuit. While L.A. County is seeking $2,500 in damages per "violation," it’s unknown what might count as a violation if it succeeds. The State of California is also targeting plastic pollution. In September, the Attorney General sued ExxonMobil over its allegedly misleading marketing practices around recycling of plastic made with its fossil fuel products. As concerns grow regarding the environmental and health impacts of plastic waste, we will continue to follow the issue including these cases in California and the international efforts for a treaty on plastics.

Related link:

AP News | “Los Angeles County Sues Pepsi and Coca-Cola Over Plastic Bottles”

[MUSIC: Nazareno Aversa, Firework Katy Perry Piano Cover]

CURWOOD: Coming up, the mysterious and threatened lives of eels. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joe Pass, “Joe’s Blues” on Intercontinental, Edel Germany GmbH]

Slippery Beast: A True Crime Natural History, with Eels

Slippery Beast: A True Crime Natural History, with Eels tells the story of how a booming poaching industry is impacting the American Eel. (Photo: Courtesy of Abrams Books)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

There are many species humans find charismatic on this Earth, from koalas, to elephants, to great apes. And then there are creatures like the eel. Slippery, slimy and hardly endearing, the most recognition they get may be as the tasty sushi staple unagi. But they also play an important ecological role in many rivers and streams. Part of the reason eels are so misunderstood may come down to how mysterious and eel-usive they are. Even eel scientists have been challenged to observe eels mating in the wild. It was only in 2022 that scientists were finally able to track mature eels to the Sargasso Sea, which includes the Bermuda Triangle, to prove that they mated there. These eel enigmas and more intrigued Ellen Ruppel Shell, author of the 2024 book Slippery Beast: A True Crime Natural History, with Eels. She joined Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

BELTRAN: So, tell us, what got you interested in writing about eels in the first place? Do you fish, by any chance?

SHELL: Actually, I'm one of the few people who has written about eels who does not fish. The short answer to your excellent question is that I did not find eels. Eels found me. And the story behind that, if you'd like to hear it, involves the guy that I call Sam in the book. It's not his real name, but he is a real person. And Sam was a handyman who I'd hired to help me fix up my house on the coast of Maine. And one day, Sam came into my kitchen to share with me that he was hoping to put together enough money to buy a boat on which he was going to teach his grandson to fish. And I said, "Sam, why don't you mix business with pleasure and get yourself a commercial fishing license to go with that boat?" And Sam said, "Well, I would do that. In fact, I used to do that, but not anymore, because of the eels." Now that kind of stopped me. I said, "What do you mean? Are you afraid the eels are going to bite you?" And he said, "No, no, I'm not talking about eels big enough to bite me. I'm talking about those baby eels. Ever since the price on those things went through the roof, it's gotten dangerous down by the river." And I said, "What do you mean? The price went through the roof?" And he said, "Well, this year, this season, they're going for about $2,500 a pound, and with money like that around, you know, people have gotten greedy, and some have gotten mean, and they have guns, and they've been cutting nets, and it's just too dangerous to fish for eels or to fish at all." And after hearing it, obviously, I couldn't resist looking into the eel and to the you know, both as a product, as a commodity, but also as this incredible fish that have attracted the attention of people, what they call eel people, since Aristotle's time. It was really an incredible story.

BELTRAN: It really is. And you said, Sam says that a pound of eels is going up for $2,500 a pound. That's a lot of dough. That's a lot of money. Tell me a little bit about how eating eel became so popular in the United States.

SHELL: Oh, well, eel has quite a history in the United States. It begins with Native Americans who relied on eels, those in the maritime states, New England, for example, also in Canada. Native Americans relied on eel to get them through the winters, because you could smoke it, you could preserve it and salt it, and it's also very high in calories and because it's a very fatty fish. But as the centuries passed, post-colonial times, eel declined in popularity, although even at the turn of the last century, say, around 1900 it was still considered a delicacy preferable to things like lobster. But then it kind of died out in popularity in the United States, until the introduction of the Japanese cuisine and sushi, which was actually introduced to United States into, you know, around early 1900s but then kind of exploded in the 1960s and 70s. So, some consider eel, which is cooked, as kind of a gateway drug to sushi. Many Americans were afraid of eating raw fish, which is sushi, but they… They would eat eel, which is always serve cooked. And since that time, with the, you know, growth and interest in Japanese cuisine and sushi in particular, eel has become more and more popular in the United States.

The American eel may look like a snake, but it is a fish. (Photo: Duane Raver, USFWS, Flickr, public domain)

BELTRAN: So, the full title of your book is “Slippery Beast: A True Crime Natural History with Eels”. This is because there's a massive eel poaching industry. How does the supply chain actually work?

SHELL: Well, you're right. It is massive. In fact, the poaching, the illicit trade in eel, freshwater eel, in particular, is the world's largest wildlife crime in terms of dollars. It's about $4 billion a year illegal industry. In the United States, we harvest these eels mostly in Maine, okay, because that's the largest fishery for baby eels in the United States, and really the only significant fishery for baby eels. But we don't grow them up in the United States. We send them to China to be grown to market sized, and then there they're usually processed. They're killed and cut into filets and sometimes coated in sauce, and then shipped back to United States. So, it's a crazy supply chain. We also don't know too much about those eel ponds in China. They don't know what goes in them, whether it's healthy or not. We're really not sure. I's not very well regulated.

BELTRAN: So, the current eel fishing industry is complicated. Is anyone trying to build a shortcut around it?

SHELL: Yes. One of them is Sara Rademaker, who has recently opened the first eel farm in the United States on the coast of Maine, and she is hoping to kind of short circuit the crazy supply chain and have the eels that are fished in Maine, caught in Maine, stay in Maine, and grown up on a farm. And she has done that, and so far, so good. She's managed to grow her first two years of eels, and her goal is to farm about 6% of the eels that are consumed the United States. And she's well on her way to doing that.

Eel is most commonly eaten in the U.S. in the form of sushi. (Photo: stu_spivack, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BELTRAN: I was shocked to find out that at some point in history, there was a competition to find an eel that would show to be pregnant or have some sort of eggs, just to try to figure out how eels reproduce. Can you tell us more about that?

SHELL: Okay, so eel people stretch all the way back to Aristotle through history. I mean, Aristotle was obsessed with eels because no one knew how they reproduced, okay? Eels were ubiquitous. They were everywhere. In some waterways, they were the most abundant fish. Until relatively recently, they've made up about as much as 50% of biomass in many, many waterways, right? So, there were all these eels, they were very, very plentiful, and yet no one had ever seen them reproduce, and no one had ever seen an eel egg. Okay, so this mystery just really obsessed people throughout history, scholars throughout history, beginning with Aristotle, who assumed that they were created through spontaneous generation, right, that they just kind of appeared out of the mud, okay? And they were pretty good argument for spontaneous generation because no one had ever seen them reproducing, or, as I said, seen an egg, or even seen a sexually mature eel in the wild. So, through centuries, scholars have puzzled what they consider to be one of the greatest mysteries of biology, that is, how do eels, again, so common a fish, how do they reproduce? And as a consequence of this, in the 1800s into the 1900s a fisherman that could find an eel that was pregnant would get a certain amount of money, and they would fake it. They would take an eel and put other species eggs in the eels and hoping that they could pass this off as an eel, a pregnant eel. Of course, it never worked, but the hopes were high for this. There was essentially a bounty on finding pregnant eels.

BELTRAN: Your book goes through all of these crazy hypotheses that scientists came up with, what were some key moments through that timeline? What were some of your favorite hypotheses?

Eels are a key part of freshwater mussel reproduction, so without eels, mussels are put under threat. And because mussels clean waterways, their destruction could lead to more polluted rivers. (Photo: James St. John, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

SHELL: Ah, yes. So, the German Benedictine abbess Hildegard of Bingen, okay, so we're talking about 1100 A.D., sometime around that time. And so, she was a noted philosopher and a composer, and she was also a medical practitioner, if you can believe it. And so, she could not get her head around the idea of, maybe, because she was a Benedictine nun, the idea that there was an immaculate conception of the eel, right? Which, if you're talking about spontaneous generation, it is essentially an immaculate conception, right? So, Hildegard's idea was that each winter, the female eel choose an appropriate stone and spits seeds onto it, and then the male spits something like milk over the seeds. And after some struggle, the male and the female together lie on top of the seeds, the male protecting them with his tail and the female blowing, quote, vital air into them until they come alive. And so, I kind of think of this as a primitive version of in vitro fertilization. And that, given that, you know, this involves eels of both genders and not spontaneous generation, it's probably one of the more romantic tellings of the eel procreation story.

BELTRAN: There's romance booming in the ocean.

SHELL: Romance is a stretch, but I'll go with it.

BELTRAN: I think a huge question people would have listening to you right now is, why don't we just breed eels? Why don't we just try to breed eels ourselves? Why have to poach them?

The nun Hildegard of Bingen believed that eels reproduced sexually by spitting seeds onto a stone. She, like many before and after her, was wrong about eel reproduction. (Photo: W. Marshall, Courtesy of the Welcome Trust, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

SHELL: We can't. We can't breed the American eel in captivity. There was one scientist who spent a long time trying to do this. He was able to coax an American eel to breed, but all the larva died. Okay? It's a very, very difficult problem, and scientists in Japan have been working for decades trying to artificially breed Japanese eel in captivity. But the American eel, we haven't come close. We just simply cannot breed eels the way we can breed things like oysters or other animals. They simply refuse to breed in captivity, which is another part of their incredible mystery, right? Why not? No one knows for sure.

BELTRAN: So, Ellen, you wrote that the scary reality of the American eel is that it is "simultaneously abundant and doomed to extinction." How is that possible?

SHELL: Well, in this I make a comparison to the passenger pigeon, which was highly, highly abundant, as we all know, some thought it to be the most common feathered creature on Earth, certainly the most common bird on Earth at one point. And everybody thought it was so common. Scientists even thought it was so common that it would never go extinct, but it was a target of hunters in the United States, right? Very popular target because it didn't move a lot, and it was very tasty, and so hunters took it on. And as the population of the passenger pigeon diminished, it became extinct, because just like the eel, there need to be a lot of passenger pigeons, for any single passenger pigeon to survive, right? Passenger pigeons are very gregarious animals. They breed in flocks, and they cannot, you know, there can't be an isolated pigeon here and there for them to survive. It's... you need quite a few. The same is true of the freshwater eel and what we saw in Japan, where they declined by something like 95% very, very quickly, could also happen in the United States. Okay, we need a lot of them to survive for any of them to survive. And that's why, even though they seem plentiful, they're still at great risk.

BELTRAN: And why is protecting the eels so important? What role do they play in our ecosystem?

Ellen Ruppel Shell is the author of Slippery Beast: A True Crime Natural History, with Eels. (Photo: Martin Shell)

SHELL: Yeah, that's a great question. Eels are what we call an indicator species, so their health oftentimes reflects the health of the water that they're in. Okay? So, what we know is that if you rid waterways that have eels, freshwater eels, of the eel, there are consequences, and those consequences vary with the waterway we're talking about. An example that I give in the book is the Susquehanna River. Okay, it's a, you know, we all know the Susquehanna. It's great American River. When eels were depleted, heavily depleted in the Susquehanna, there became a great decline in the freshwater mussel and the reason for that is because eels were kind of a transportation system for the freshwater mussel larva. It helped scatter the freshwater mussel larva along the bottom of the river and kept it going. So, when the eels died off, the mussels died off, and mussels are filter feeders that keep waterways clean. So, without the mussels, the waterways became polluted. When you take that eel out, you screw everything up.

BELTRAN: Ellen, I have to ask you, after all this research and talking to all kinds of different eel people. How do you feel about eels? Do you eat them?

SHELL: Yes, I do eat eels. I wasn't smitten by the eel, as so many people in the book were. I'm not enraptured to the eel, but I'm enraptured to the people who are enraptured to the eel. Okay, the people are what brought me to this story and hold me to this story.

DOERING: Ellen Ruppel Shell is the author of Slippery Beast: A True Crime Natural History, with Eels. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

Related links:

- Purchase Slippery Beast and support both local bookstores and Living on Earth.

- Learn more about the American Eel.

- Purchase American raised eel.

[MUSIC: Eels, “Time” on EELS TIME!, Works under exclusive license to Play It Again Sam]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, The Sierra Nevada of Santa Marta located in Northern Colombia is one of the highest coastal mountain ranges on earth and features many different ecosystems like rainforests, savannas, tropical dry forests, glaciers, deserts and coral reefs. It’s also home to the Kankuamo people who consider it “the heart of the world”. Carmen Rosa Guerra is the Global Agenda Coordinator of the Indigenous Kankuamo Organization and a defender of their sacred territory. She attended the COP 16 biodiversity conference in Cali, Colombia where formal steps were agreed to more fully recognize how much indigenous peoples are key drivers in conserving nature. We asked Carmen about COP 16 and her home, Colombia's Sierra Nevada, a title that translates into English as "snowy mountains."

ROSA GUERRA: It's beautiful, it's perfection itself. It have all the temperatures. So, you have snow in the top and you have the beach at the bottom. So, you can actually visit the top and you are going to be with jacket and then you are going to be in a bathing suit because you are in the beach, but also, it's really specific each territory. We are for indigenous nations, so we are all together protecting our territory and we all have kind of the same tradition. So that's why we only have one traditional knowledge system. We are a really strong and resilient indigenous nation. We understand that we are not protecting Mother Earth, it’s on the contrary, Mother Earth is protecting us. The first message that we sent in COP 16 was that.

CURWOOD: Indigenous communities next time on Living on Earth!

[MUSIC: Alfredo Rolando Ortiz, Rafael Ricardo, “Quise Manchar Tu Alma” on Arpa Vallenata]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Josh Croom, Daniela Faria, “Mehek” Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, and El Wilson.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And we always welcome your feedback at comments at loe dot org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth