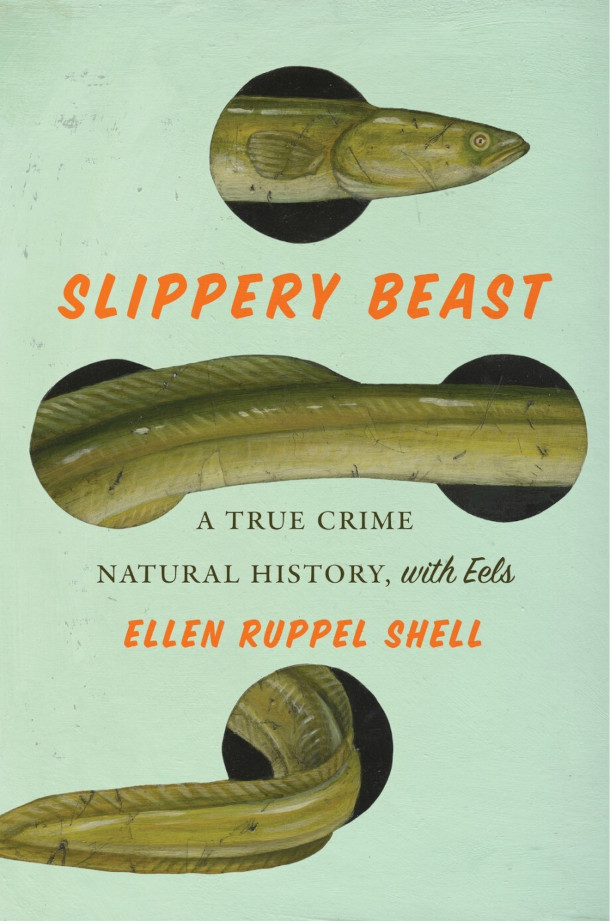

Slippery Beast: A True Crime Natural History, with Eels

Air Date: Week of November 8, 2024

Slippery Beast: A True Crime Natural History, with Eels tells the story of how a booming poaching industry is impacting the American Eel. (Photo: Courtesy of Abrams Books)

Eels play an important ecological role in many rivers and streams, but they’re so eel-usive that even eel scientists have been challenged to observe them mating in the wild. Ellen Ruppel Shell is author of the 2024 book Slippery Beast: A True Crime Natural History, with Eels, and she sheds light on the eel’s murky ecology and path through the seafood industry.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

There are many species humans find charismatic on this Earth, from koalas, to elephants, to great apes. And then there are creatures like the eel. Slippery, slimy and hardly endearing, the most recognition they get may be as the tasty sushi staple unagi. But they also play an important ecological role in many rivers and streams. Part of the reason eels are so misunderstood may come down to how mysterious and eel-usive they are. Even eel scientists have been challenged to observe eels mating in the wild. It was only in 2022 that scientists were finally able to track mature eels to the Sargasso Sea, which includes the Bermuda Triangle, to prove that they mated there. These eel enigmas and more intrigued Ellen Ruppel Shell, author of the 2024 book Slippery Beast: A True Crime Natural History, with Eels. She joined Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

BELTRAN: So, tell us, what got you interested in writing about eels in the first place? Do you fish, by any chance?

SHELL: Actually, I'm one of the few people who has written about eels who does not fish. The short answer to your excellent question is that I did not find eels. Eels found me. And the story behind that, if you'd like to hear it, involves the guy that I call Sam in the book. It's not his real name, but he is a real person. And Sam was a handyman who I'd hired to help me fix up my house on the coast of Maine. And one day, Sam came into my kitchen to share with me that he was hoping to put together enough money to buy a boat on which he was going to teach his grandson to fish. And I said, "Sam, why don't you mix business with pleasure and get yourself a commercial fishing license to go with that boat?" And Sam said, "Well, I would do that. In fact, I used to do that, but not anymore, because of the eels." Now that kind of stopped me. I said, "What do you mean? Are you afraid the eels are going to bite you?" And he said, "No, no, I'm not talking about eels big enough to bite me. I'm talking about those baby eels. Ever since the price on those things went through the roof, it's gotten dangerous down by the river." And I said, "What do you mean? The price went through the roof?" And he said, "Well, this year, this season, they're going for about $2,500 a pound, and with money like that around, you know, people have gotten greedy, and some have gotten mean, and they have guns, and they've been cutting nets, and it's just too dangerous to fish for eels or to fish at all." And after hearing it, obviously, I couldn't resist looking into the eel and to the you know, both as a product, as a commodity, but also as this incredible fish that have attracted the attention of people, what they call eel people, since Aristotle's time. It was really an incredible story.

BELTRAN: It really is. And you said, Sam says that a pound of eels is going up for $2,500 a pound. That's a lot of dough. That's a lot of money. Tell me a little bit about how eating eel became so popular in the United States.

SHELL: Oh, well, eel has quite a history in the United States. It begins with Native Americans who relied on eels, those in the maritime states, New England, for example, also in Canada. Native Americans relied on eel to get them through the winters, because you could smoke it, you could preserve it and salt it, and it's also very high in calories and because it's a very fatty fish. But as the centuries passed, post-colonial times, eel declined in popularity, although even at the turn of the last century, say, around 1900 it was still considered a delicacy preferable to things like lobster. But then it kind of died out in popularity in the United States, until the introduction of the Japanese cuisine and sushi, which was actually introduced to United States into, you know, around early 1900s but then kind of exploded in the 1960s and 70s. So, some consider eel, which is cooked, as kind of a gateway drug to sushi. Many Americans were afraid of eating raw fish, which is sushi, but they… They would eat eel, which is always serve cooked. And since that time, with the, you know, growth and interest in Japanese cuisine and sushi in particular, eel has become more and more popular in the United States.

The American eel may look like a snake, but it is a fish. (Photo: Duane Raver, USFWS, Flickr, public domain)

BELTRAN: So, the full title of your book is “Slippery Beast: A True Crime Natural History with Eels”. This is because there's a massive eel poaching industry. How does the supply chain actually work?

SHELL: Well, you're right. It is massive. In fact, the poaching, the illicit trade in eel, freshwater eel, in particular, is the world's largest wildlife crime in terms of dollars. It's about $4 billion a year illegal industry. In the United States, we harvest these eels mostly in Maine, okay, because that's the largest fishery for baby eels in the United States, and really the only significant fishery for baby eels. But we don't grow them up in the United States. We send them to China to be grown to market sized, and then there they're usually processed. They're killed and cut into filets and sometimes coated in sauce, and then shipped back to United States. So, it's a crazy supply chain. We also don't know too much about those eel ponds in China. They don't know what goes in them, whether it's healthy or not. We're really not sure. I's not very well regulated.

BELTRAN: So, the current eel fishing industry is complicated. Is anyone trying to build a shortcut around it?

SHELL: Yes. One of them is Sara Rademaker, who has recently opened the first eel farm in the United States on the coast of Maine, and she is hoping to kind of short circuit the crazy supply chain and have the eels that are fished in Maine, caught in Maine, stay in Maine, and grown up on a farm. And she has done that, and so far, so good. She's managed to grow her first two years of eels, and her goal is to farm about 6% of the eels that are consumed the United States. And she's well on her way to doing that.

Eel is most commonly eaten in the U.S. in the form of sushi. (Photo: stu_spivack, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BELTRAN: I was shocked to find out that at some point in history, there was a competition to find an eel that would show to be pregnant or have some sort of eggs, just to try to figure out how eels reproduce. Can you tell us more about that?

SHELL: Okay, so eel people stretch all the way back to Aristotle through history. I mean, Aristotle was obsessed with eels because no one knew how they reproduced, okay? Eels were ubiquitous. They were everywhere. In some waterways, they were the most abundant fish. Until relatively recently, they've made up about as much as 50% of biomass in many, many waterways, right? So, there were all these eels, they were very, very plentiful, and yet no one had ever seen them reproduce, and no one had ever seen an eel egg. Okay, so this mystery just really obsessed people throughout history, scholars throughout history, beginning with Aristotle, who assumed that they were created through spontaneous generation, right, that they just kind of appeared out of the mud, okay? And they were pretty good argument for spontaneous generation because no one had ever seen them reproducing, or, as I said, seen an egg, or even seen a sexually mature eel in the wild. So, through centuries, scholars have puzzled what they consider to be one of the greatest mysteries of biology, that is, how do eels, again, so common a fish, how do they reproduce? And as a consequence of this, in the 1800s into the 1900s a fisherman that could find an eel that was pregnant would get a certain amount of money, and they would fake it. They would take an eel and put other species eggs in the eels and hoping that they could pass this off as an eel, a pregnant eel. Of course, it never worked, but the hopes were high for this. There was essentially a bounty on finding pregnant eels.

BELTRAN: Your book goes through all of these crazy hypotheses that scientists came up with, what were some key moments through that timeline? What were some of your favorite hypotheses?

Eels are a key part of freshwater mussel reproduction, so without eels, mussels are put under threat. And because mussels clean waterways, their destruction could lead to more polluted rivers. (Photo: James St. John, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

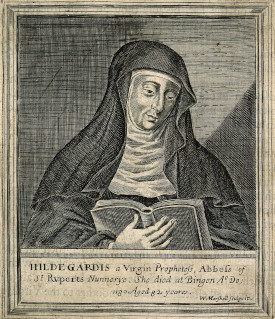

SHELL: Ah, yes. So, the German Benedictine abbess Hildegard of Bingen, okay, so we're talking about 1100 A.D., sometime around that time. And so, she was a noted philosopher and a composer, and she was also a medical practitioner, if you can believe it. And so, she could not get her head around the idea of, maybe, because she was a Benedictine nun, the idea that there was an immaculate conception of the eel, right? Which, if you're talking about spontaneous generation, it is essentially an immaculate conception, right? So, Hildegard's idea was that each winter, the female eel choose an appropriate stone and spits seeds onto it, and then the male spits something like milk over the seeds. And after some struggle, the male and the female together lie on top of the seeds, the male protecting them with his tail and the female blowing, quote, vital air into them until they come alive. And so, I kind of think of this as a primitive version of in vitro fertilization. And that, given that, you know, this involves eels of both genders and not spontaneous generation, it's probably one of the more romantic tellings of the eel procreation story.

BELTRAN: There's romance booming in the ocean.

SHELL: Romance is a stretch, but I'll go with it.

BELTRAN: I think a huge question people would have listening to you right now is, why don't we just breed eels? Why don't we just try to breed eels ourselves? Why have to poach them?

The nun Hildegard of Bingen believed that eels reproduced sexually by spitting seeds onto a stone. She, like many before and after her, was wrong about eel reproduction. (Photo: W. Marshall, Courtesy of the Welcome Trust, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

SHELL: We can't. We can't breed the American eel in captivity. There was one scientist who spent a long time trying to do this. He was able to coax an American eel to breed, but all the larva died. Okay? It's a very, very difficult problem, and scientists in Japan have been working for decades trying to artificially breed Japanese eel in captivity. But the American eel, we haven't come close. We just simply cannot breed eels the way we can breed things like oysters or other animals. They simply refuse to breed in captivity, which is another part of their incredible mystery, right? Why not? No one knows for sure.

BELTRAN: So, Ellen, you wrote that the scary reality of the American eel is that it is "simultaneously abundant and doomed to extinction." How is that possible?

SHELL: Well, in this I make a comparison to the passenger pigeon, which was highly, highly abundant, as we all know, some thought it to be the most common feathered creature on Earth, certainly the most common bird on Earth at one point. And everybody thought it was so common. Scientists even thought it was so common that it would never go extinct, but it was a target of hunters in the United States, right? Very popular target because it didn't move a lot, and it was very tasty, and so hunters took it on. And as the population of the passenger pigeon diminished, it became extinct, because just like the eel, there need to be a lot of passenger pigeons, for any single passenger pigeon to survive, right? Passenger pigeons are very gregarious animals. They breed in flocks, and they cannot, you know, there can't be an isolated pigeon here and there for them to survive. It's... you need quite a few. The same is true of the freshwater eel and what we saw in Japan, where they declined by something like 95% very, very quickly, could also happen in the United States. Okay, we need a lot of them to survive for any of them to survive. And that's why, even though they seem plentiful, they're still at great risk.

BELTRAN: And why is protecting the eels so important? What role do they play in our ecosystem?

Ellen Ruppel Shell is the author of Slippery Beast: A True Crime Natural History, with Eels. (Photo: Martin Shell)

SHELL: Yeah, that's a great question. Eels are what we call an indicator species, so their health oftentimes reflects the health of the water that they're in. Okay? So, what we know is that if you rid waterways that have eels, freshwater eels, of the eel, there are consequences, and those consequences vary with the waterway we're talking about. An example that I give in the book is the Susquehanna River. Okay, it's a, you know, we all know the Susquehanna. It's great American River. When eels were depleted, heavily depleted in the Susquehanna, there became a great decline in the freshwater mussel and the reason for that is because eels were kind of a transportation system for the freshwater mussel larva. It helped scatter the freshwater mussel larva along the bottom of the river and kept it going. So, when the eels died off, the mussels died off, and mussels are filter feeders that keep waterways clean. So, without the mussels, the waterways became polluted. When you take that eel out, you screw everything up.

BELTRAN: Ellen, I have to ask you, after all this research and talking to all kinds of different eel people. How do you feel about eels? Do you eat them?

SHELL: Yes, I do eat eels. I wasn't smitten by the eel, as so many people in the book were. I'm not enraptured to the eel, but I'm enraptured to the people who are enraptured to the eel. Okay, the people are what brought me to this story and hold me to this story.

DOERING: Ellen Ruppel Shell is the author of Slippery Beast: A True Crime Natural History, with Eels. She spoke with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

Links

Purchase Slippery Beast and support both local bookstores and Living on Earth.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth