Robin Wall Kimmerer on The Serviceberry

Air Date: Week of November 22, 2024

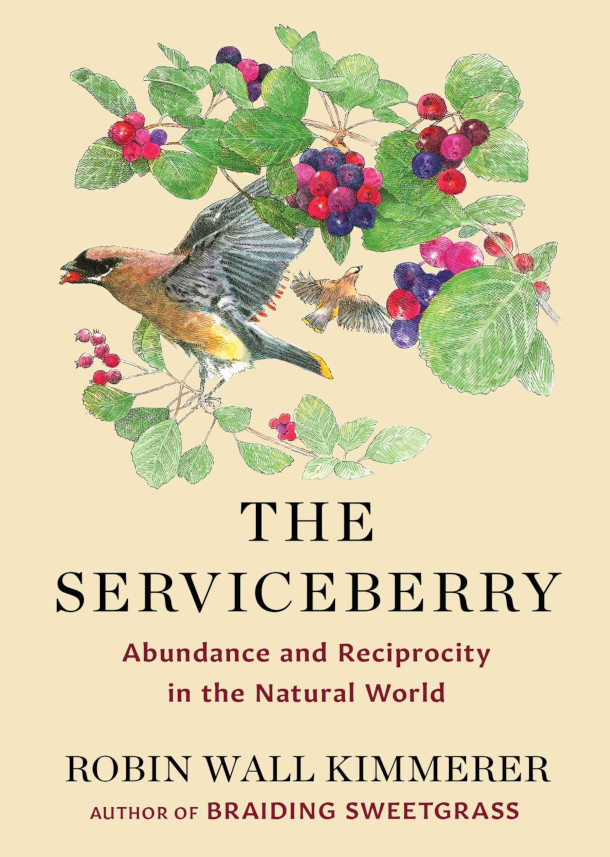

The cover of The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer beautifully encapsulates the book's themes of nature’s abundance and reciprocity. (Photo: Courtesy of Robin Wall Kimmerer)

Braiding Sweetgrass author Robin Wall Kimmerer is back with a new book that continues her explorations of gift economies. Robin Wall Kimmerer joins Host Jenni Doering to share insights from The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World and how gift economies can offer an alternative to overconsumption.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

You’ve seen the prices at the grocery store, maybe even cringed a little. Could a dozen eggs really cost that much? And $7 for a gallon of organic milk? That’s the capitalist society we live in, where we pay the current market value. But for most of human history, no money changed hands and even bartering is thought to be less than ten thousand years old. Instead, we got what we needed and took care of each other thanks to gift economies. Rather than selling goods and services and accumulating wealth, in a gift economy they are given freely in a web of reciprocity. Robin Wall Kimmerer is perhaps best known as the author of Braiding Sweetgrass, about living in a reciprocal relationship with other beings and the gifts of the Earth. And she’s back with a new book that continues her explorations of gift economies. It’s called The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World. Robin Wall Kimmerer is a member of the Citizen PotaWAtomi nation and professor of environmental biology at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, and she joins us now. Hi Robin and welcome to Living on Earth!

KIMMERER: Hi, Jenni, thanks for the invitation to join you.

DOERING: So what is a serviceberry, and why is it significant to you?

KIMMERER: A serviceberry is a beautiful genus of plants. It doesn't look like much. In fact, I tell my students, you can tell a serviceberry because it's kind of generic looking in that the leaves are just round, smooth, gray bark. But when it flowers and fruits, it's a whole different story. In the springtime, there's just a froth of white blossoms, and then in mid summer, it's just heavily laden with these red, juicy fruits. You can mostly find it around edges of water, edges of trails. It's an ecotone species that kind of likes the forest edge.

DOERING: And it sounds like it brings this abundance in season, when these berries are ripe, all kinds of animals and people, including yourself, enjoy these berries. So what does that abundance of serviceberries lead to?

KIMMERER: Well, the abundance of serviceberries leads to an abundance of life all around because, for example, in the early spring, there's a whole group of bees that rely entirely on those early spring flowers, right? So it's feeding the pollinator community. And then later, when the berries start to ripen, oh, you can find a serviceberry tree, because of all the birds, they are all just gathering there, and they're so noisy. I use them for prospecting. That's how I find a serviceberry tree is I listen for the birds, so it's feeding that whole community as well. You know, those are the obvious ways that it's engaged, but it's also an important host for lots of different larvae of butterflies and the whole food web that grows around this tree.

DOERING: And you yourself describe in this book, harvesting, putting those berries into a pail, and then being able to share that abundance with your neighbors.

KIMMERER: That's right, they are so abundant that on my neighbor's farm, where they plant the Western variety of serviceberry known as saskatoons, they are just an exemplar of abundance. You can just pick them by the handful.

The serviceberry is a small, sweet fruit, deep purple or reddish-blue when ripe, with a flavor resembling a mix of blueberries and almonds. It's rich in nutrients and perfect for fresh eating, baking, or preserves. (Photo by Melissa McMaster, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: And you can turn them into a pie?

KIMMERER: Oh, they make a good pie. They make good jam, good syrup. But you know, traditionally, a lot of native cultures, particularly Western cultures, used it's the source of pemmican. It's the major fruit for pemmican. So the berries would be dried and pounded into this really super food. The berries are really rich in antioxidants and vitamin C. So it was an excellent choice to mix into the original energy bars, which were pemmican.

DOERING: And, pemmican, remind me is that a mix of berries and meat?

KIMMERER: It is, yeah, the berries are dried and pounded, and elk or venison is also dried and pounded, and then the whole thing is bound together with rendered fat. So it is quite literally the original energy bar, and our people used it for travel food and for trade, etc. It was a really important way to store excess calories.

DOERING: Tell me about the connection here between this idea of a gift economy and the way that resources are shared in the natural world. Could you maybe trace the path of a serviceberry for us? Maybe the berry itself falls to the ground or gets eaten by a bird, and what happens next?

A portrait of Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of The Serviceberry, reflecting her deep connection to nature and ecological knowledge. (Photo: The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation)

KIMMERER: Well, I think it's important to preface that by talking about what I mean by gift. And a gift in my thinking, and this reflects a lot of ancestral teachings. A gift is something that we have not earned, and yet it comes to us, someone bestows it upon you. So let's follow the thread that you suggest, Jenni, of the growth of a serviceberry, the sun. The sun is the energy that animates all of it, and so all of that sunshine, through photosynthesis, turns into the body of the serviceberry. One could argue that the sun, the sun's energy, is a gift we have not earned it, and yet it comes. But that gift of photosynthesis is then shared with others. It's shared with the larvae of those caterpillars that are eating the leaves. It's shared in the abundance of fruits that the robins and the cedar waxwings and the blackbirds are all coming to feast on. The gift is shared. It's passed on. And then, of course, those birds that are splattering bird poop all over the ground, all of that nitrogen, right, is feeding the food web below ground and building soil. The fox that comes and snatches one of those robins off the ground while it's all full of berries, the gift stays in motion. And so if we start with the premise that what life produces for us is a gift, it's all a gift economy.

DOERING: In the book, you quote an indigenous Brazilian hunter saying, "Store my meat? I store my meat in the belly of my brother." Can you tell me the story of that quote?

The serviceberry fruit, sweet and tart, supports pollinators and birds, playing a vital role in ecosystems. (Photo: Unsplash, public domain)

KIMMERER: Yes, that quote, that story that was shared by an anthropologist, linguist working with Amazonian indigenous peoples, is at the heart of what we understand to be a gift economy. In this story, the hunter had been successful that day and came back with a really sizable animal. And so the anthropologist linguist was talking with them and saying, "Well, how are you going to store the meat? Are you going to dry it or salt it? What will you do to store the meat?" And he reports the astonishment of the hunter, saying, "Store my meat. Why would I do that?" And so he asks again, and he said, "Well, no, I don't store my meat. I store my meat in the belly of my brother." Meaning he wasn't going to hold on to and accumulate this bonus, this surplus of meat. He was going to have a feast. He was going to invite his neighbors, his friends, his extended family, all to come and benefit from what the forest had provided him in the form of game. And the anthropologist was astonished because that breaks all the rules of Western economics. Doesn't it? That says, "Well, you should hold on to that for yourself. You should store it so that when the hungry time comes, as it inevitably does, you'll have food security." But essentially, the lesson taught by that story is there are other ways to have material security, food security, and that is through relationship. That hunter was saying, when I feed my neighbors, when I feed my community, they're going to feed me when their nets are full of fish, they're going to invite me to a feast if I need their help, we've established good relationships of trust and kinship, so they'll take care of me, because I'm taking care of them. And that is the heart of a gift economy. No money is exchanged. The gift stays in motion. It creates this network of relationships that create the kind of material security that market economics is designed to produce.

DOERING: And in our own lives, what advice do you have for centering gift economies, participating in those and reciprocity in our lives while also living in this modern world, this complex world?

Before it bears fruit, the serviceberry plant is characterized by its delicate white flowers in early spring, which attract pollinators. (Photo: Unsplash, public domain)

KIMMERER: Well, the book is full of examples of micro scale gift economies. Some of the ones that seem most appropriate to think about in a time of climate crisis. What is it that's driving the climate crisis? It's hyper consumption, overconsumption, and gift economies suggest. You know what? We don't all need to own everything that we need in life. We don't need to each go out and buy a lawnmower. We don't. We need, perhaps one for the neighborhood. And those kinds of neighborly sharing help to stem hyper consumption, but you also create a web of mutual relationship, which I think as human people, particularly in an industrialized society, we crave. We crave that sense of belonging, of being known, of being needed in our communities. So that's how I think about the role of gift economies as a sharing economy that produces abundance without market regulation. And so I think gift economies can live in coexistence with the dominant model of economics, if we encourage them. And I don't want in any way this idea of trying to promulgate small, highly localized gift economies to in anyway excuse us from rethinking capitalism and damage associated with it. In the book, I talk quite a lot about the ethical jeopardy of extractive systems and the cost that that has in the well being of the planet, and while we could celebrate and cultivate small scale gift economies, that doesn't mean we aren't still complicit with this larger system that we need to seriously rethink.

DOERING: Can you describe for me scaling up this gift economy idea and how we can kind of work with this complex, global, interconnected world that we have, and integrate some more of this gift economy thinking into that system?

KIMMERER: You know, I began looking for gift economies in modern society after having learned about them from both ancestral and contemporary indigenous societies, and I found them everywhere, once you kind of know what to look for. One of the examples that I like to start with is, you know, when you read a good book, you want to pass it on to a friend. You don't sell that book to your friend. You give it to them. There it is a tiny, little gift economy. But how does that scale up? Well, in my neighborhood, we have little free libraries where people say, oh, let's leave our books here to share with one another. That's a gift economy. I think about public libraries as gift economies. We don't own the books. That's the idea. We have abundance of literature because we share. So that continuum from the giving a book to a friend, to little free libraries to public libraries, gives us a hint at what gift economies can look like. And at a larger scale, the way that we use our financial resources to invest in commons. Common resources, like libraries, offers us an opening as well. What about things like common lands of parks and trails and water? Those are things we don't each of us own. We care for them in common. We enjoy them in common. So gift economies are also an invitation to the economy of the commons, rather than of private property and individual ownership.

DOERING: Before you go, Robin, in this season of harvest, how does giving thanks connect with abundance and reciprocity?

KIMMERER: Gratitude is such an important human response to the abundance of the world and deep gratitude. No, I don't mean just like that polite toss off thank you. I mean the kind of gratitude where you recognize that your life is totally dependent upon the lives of other beings that you would not exist without water or those berries or that medicine, that kind of deep gratitude that allows us to look at the world of abundance and feel as if you have everything that you need. Let's be clear, everything that I need might be quite different than everything that I want. But everything that I need, I have and is provided for me as a gift from Mother Earth. It also makes you feel as if you have everything, and so why do you need to buy anything else? It creates a sense of sufficiency and enoughness that puts the brakes on consumption. I believe eco psychologists have demonstrated that people who practice gratitude consume less than people who don't. To think about the world as gift is to think about the world not as objects that belong to us, but as stories. That shirt that you might want to buy, it's not just as an object, is it? It's the product of many hands, and it has consequences. It has costs. And so I think one of the most important things we can do as consumers is to really think about the stories associated with those objects. Was that fiber in the shirt that you're interested in, is it recycled? Is it part of a circular economy, or is it part of an extractive economy? And when we see the world as gift, we see that whole story of knowing where everything came from, and then that's what helps something be a gift, not a commodity is we know all the relationships that are associated with it. But that same attention to the story of an object allows us to decide whether we're going to buy it or not. Are we going to participate in a dishonorable harvest, or are we only going to purchase those things which safeguard life, make life better?

DOERING: Robin Wall Kimmerer is the author of The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World and other books. Thank you so much, Robin.

KIMMERER: Thank you.

Links

Purchase a copy of The Serviceberry (Affiliate link supports Living on Earth and local bookstores)

Discover insightful reader reviews and more about The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth