November 22, 2024

Air Date: November 22, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Trump's Anti-Green Rollback Team

View the page for this story

President-elect Trump has nominated three men to run federal departments critical for climate and environmental protection with a mandate to roll back green rules and regulations. Vermont Law Emeritus Professor Pat Parenteau is among the critics of these choices and joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the nominees, former US Rep. Lee Zeldin for EPA, Liberty Energy CEO Chris Wright for Energy and North Dakota Gov. Doug Burgum for Interior. (12:20)

Biden Climate Cash in Jeopardy

View the page for this story

Given President-elect Trump’s vow to dismantle the Inflation Reduction Act, some communities are concerned about their applications for climate and environmental justice funding. Jillian Blanchard of Lawyers for Good Government talks with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill about what’s on the line and why bipartisan support for the IRA may help preserve some federal support. (08:40)

Shiitake Mushroom Harvest

/ Aynsley O’NeillView the page for this story

A year after inoculating a log with shiitake mushroom spawn and reporting about it on Living on Earth, Producers Aynsley O’Neill and Jenni Doering harvested and cooked up the first crop. Jenni Doering walks Host Steve Curwood through moments from the mushroom cooking adventure, which didn’t go quite as smoothly as planned. (07:07)

Robin Wall Kimmerer on The Serviceberry

View the page for this story

Braiding Sweetgrass author Robin Wall Kimmerer is back with a new book that continues her explorations of gift economies. Robin Wall Kimmerer joins Host Jenni Doering to share insights from The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World and how gift economies can offer an alternative to overconsumption. (17:04)

Earth Prayer

View the page for this story

Nulhegan Abenaki storyteller Joe Bruchac joins Host Steve Curwood to deliver his poem of gratitude for the gifts of the Earth, called “Earth Prayer.” (02:18)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

241122 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Jillian Blanchard, Joe Bruchac, Robin Wall Kimmerer, Pat Parenteau

REPORTERS: Aynsley O’Neill

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

President-elect Trump’s picks to lead environmental agencies come under fire from climate activists.

PARENTEAU: Instead of a head of the Dept. of Energy that’s seeing the promise and the critical need to scale up renewables and cleaner sources of energy, he wants to take us back to the 1900s — back to the era of coal and oil and gas.

CURWOOD: And in this time of harvest and abundance we consider the value of gift economies.

KIMMERER: I began looking for gift economies in modern society after having learned about them from both ancestral and contemporary indigenous societies, and I found them everywhere, once you kind of know what to look for.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth—stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Trump's Anti-Green Rollback Team

President-elect Donald Trump has pointed to Lee Zeldin, who has supported Trump since his first presidential campaign in 2016, as his choice for head of the Environmental Protection Agency. (Photo: Shaleah Craighead, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

President-elect Trump has unveiled his choices to run three of the federal departments critical for climate and environmental protection. Activists have raised a chorus of concern and criticism. Vermont Law and Graduate School emeritus professor Pat Parenteau is among them, and he joins us now to share why these picks make him worried. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Pat!

PARENTEAU: Hey, Steve, it's good to be with you.

CURWOOD: So Pat. Your credentials include a number of years as regional counsel for the Environmental Protection Agency, and, of course, being a law professor. How are you reacting to President-elect Trump tapping former New York Congressman Lee Zeldin as the next head of the EPA?

PARENTEAU: Well, I guess it's damning with faint praise, but it could have been worse. Frankly, he's not Scott Pruitt. Zeldin does have a record of, for example, supporting strong measures to clean up Long Island Sound, which is another one of the estuaries that are heavily impacted by nutrient pollution and so forth. And he's come out in favor of strong regulation on PFAS and other forever chemicals but, and here's the big but, he's now under the thumb of Trump and the White House with a mandate to deregulate, and you can be sure that whatever you know credentials or praise he might have won before is not going to be his mantra now as EPA Administrator. His job is to begin to roll back all of Biden's climate and environmental policies just the way it worked in Trump 1 where there was over 100 different rules and policies enacted, and I'm sure we're going to see many of the same and probably more so.

CURWOOD: What do you see on the chopping block in terms of rules this time around?

PARENTEAU: Trump has said repeatedly, day one, he's going after the so called tailpipe regulations. These are both fuel economy rules that EPA adopts under the Clean Air Act to deal with a whole variety of pollutants. It's not just climate and carbon and greenhouse gasses. It's lead. It's volatile organic compounds. It's ozone and asthma driving pollutants. So it's, you know, the tailpipe rules are classic pollution control rules that EPA has been using since 1970 since the adoption of the Clean Air Act, which has resulted in meaningful improvements in air all across the country. But there are still many pockets of serious air pollution problems, some of which are interstate problems that only EPA can deal with. So we're going to see, as he says, from day one, targeting these very important pollution control regulations under the Clean Air Act, and right on the heels of that we're going to see them going after the power plant rules and the latest iteration from the Biden administration taking its cue from the Supreme Court's decision in the infamous West Virginia case where it invalidated Obama's Clean Power Plan. EPA said, all right, Supreme Court, if you're telling us we can only require technology improvements at each individual coal plant, then we will do that, and we will use what the industry has been touting as the answer to fossil fuel pollution, which is carbon capture and sequestration. And here's what we'll do. We'll give coal companies ample time to decide whether they want to phase these older coal plants out and replace them with cleaner either gas plants or, of course, ideally, with solar and wind and geothermal and other cleaner sources of energy, will give you a runway of time to 2032 to decide, are you going to continue burning these dirty old coal plants, and if you are going to continue to use them, then you're going to have to install 90% removal of carbon with sequestration. So these two rules alone are the largest regulatory moves to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions. But without these two rules and one other rule dealing with methane emissions from oil and gas industry, without these three big rules, which I'm sure Zeldin is going to go after, we're not going to have at the federal level any meaningful regulation of greenhouse gas emissions from some of the major sources.

Many of Donald Trump’s rollbacks during his first term as president were successfully challenged in the courts. Trump has already pledged to roll back a number of energy and environmental policies from the Biden administration. (Photo: United States Senate, Wikimedia Common, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So it takes a while, though, to make a rule, doesn't it Pat, and also to break it, to bust it down. I mean, it seems like I remember when the Obama administration was trying to do their power plant rule, it was like a four year process to get it promulgated. I mean, these are complicated rules. Even if former congressman Zeldin moves at warp speed, how quickly could he get this stuff rolled back?

PARENTEAU: That's going to take years, and if he doesn't learn from the mistakes of Trump 1 and Pruitt and Wheeler, which are the two administrators under Trump 1, if he doesn't learn from their mistakes, which led the courts to reverse them over and over and over again. They lost, Trump 1, over 80% of the legal challenges to their rollbacks, so you might think they'll be smarter this time around, but your point about taking the time necessary to do it right could be a problem for Trump and Zeldin if they really want to show progress on their regulatory rollback agenda. So they're probably going to make mistakes, they're probably going to cut some corners. They're probably going to shortchange some of the procedural requirements under what we call the Administrative Procedure Act. And you can be sure the environmental community, the public health community, they're already gearing up for the battle to come, and they are going to challenge every single one of these moves, and there are still judges on the federal bench. There are a lot of Trump judges, and probably more to come, but there are still a lot of judges out there on the federal bench that are not simply going to roll over and rubber stamp what Zeldin is going to want to do. There are some judges, particularly in the Fifth Circuit, that may be inclined, more inclined toward that direction. But there are a lot of judges who are going to say, no, the law is the law, and if you want to make changes, you're going to have to do it carefully and with due attention to the requirements of law. And so I see many years actually, of litigation and battles we're not going to win them all, those of us that are trying to defend some of these regulations, but I don't think Trump and Zeldin are going to be able to move as fast as they think they're going to be able to go.

Chris Wright, Donald Trump’s appointee for the Department of Energy, is the CEO of Liberty Energy and is a supporter of natural gas and geothermal energy. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So President-elect Trump has also selected Chris Wright, who is the CEO of a major fracking firm, Liberty Energy, to be head of the Department of Energy. What do you see coming up for that department with him at the helm?

PARENTEAU: With regard to the DOE secretary, not only does he deny that climate change is a crisis, but he also says we are not in an energy transition. You know, he's denying what the marketplace is showing with regard to solar and wind being, solar in particular, the cheapest forms of electricity generation in the world. He's denying the impact of EVs and electric vehicles on the transportation systems, and the fact that major automakers in the United States and globally are already factoring in plans for ramping up EV production. A lot of that has to do with the inflation Reduction Act and whether some of the incentives for EVs are going to remain in place. That's another topic to discuss. But the point is this Department of Energy Secretary is already said he's going to begin clawing back some of the inflation reduction money that hasn't yet been obligated, and that he is going to accelerate the approval. DOE does have regulatory authority over LNG operations, and he's going to accelerate the licensing of LNG facilities, so instead of a head of the Department of Energy that's seeing the promise and the critical need to scale up renewables and cleaner sources of energy, he wants to take us back to the 1900s, back to the era of coal and oil and gas.

CURWOOD: A lot to unpack here, Pat. President-elect Trump has also picked the governor of North Dakota, Doug Burgum, to head up the Department of Interior, which manages our nation's public lands and waters, and has also been an announcement that he would take hold of a National Energy Council. What do you make of that appointment?

Doug Burgum, current governor of North Dakota and Donald Trump’s pick for the head of the Department of the Interior, is expected to prioritize increasing energy production and output from public lands and waters in the United States, as underscored by his state’s strong ties to the fossil fuel industry. (Photo: Senior Master Sgt. David H Lipp, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

PARENTEAU: Right. I mean, you know, he's stacking the deck with loyalists and also people like Burgum, who has a track record of being able to advance the fossil fuel agenda as governor of North Dakota, a major fossil fuel state, he knows the industry, he knows the business. He doesn't know the Department of Interior that well. He's got a lot to learn. That's a massive department with multiple agencies with conflicting missions. You know, everything from the Fish and Wildlife Service to the Bureau of Land Management to the agency that licenses offshore oil and gas development. But there's no doubt that he's going to try to boost oil and gas leasing on public lands. He understands that part of it, but we have, at this point an excess of surplus energy in the United States, we're a net exporter. In fact, we're the biggest exporter of oil and gas in the world. And he wants to lift the pause that Biden had put on construction of new LNG export terminals just to try to catch up with the environmental impacts of what all this LNG development is doing. So when Burgum tries to say, I'm going to put a lot more oil and gas on the market, including drilling places like the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge or drilling in national monuments, which Trump did the first go around with Bears Ears. You know, Burgum might think that just by offering a lot of leases, he's going to ramp up oil production. It doesn't necessarily follow a lot of this leasing is going to be speculative. There's not really a demand for this. The price of gasoline is going down. Might go back up again. We don't know, it's a global market, but right now it's soft, right? So there's no demand to put a lot more oil and gas under lease than is already under lease, so we'll see how this goes. It is sure to be challenged as well. A lot of the challenges to oil and gas development from Trump 1 were successful because they weren't considering the downstream effects of burning all of this oil and gas we're putting into the market. And the courts were quick to jump on that and say, under the National Environmental Policy Act and other statutes, the Endangered Species Act and others, you have to consider what putting all of this oil and gas into the marketplace is going to do to the climate, and at least think about whether that's a good idea and whether there might be alternative uses of public land for solar and wind and other generation sources. So again, a lot of litigation, a lot of uncertainty, a lot of chaos around oil and gas leasing.

Biden’s electric vehicle (EV) tax credits may face abolition or deep cuts cut under Trump’s administration, despite many motor companies ramping up electric production. (Photo: California Energy Commission, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And the market. How do you think the markets are going to respond to this push?

PARENTEAU: I think the markets have gotten worried somewhat about constantly ramping up production. You know, bankers and brokers are smart people. They can read the science and the analysis of stranded assets. They can understand financial risk. They can see the physical risks of climate change. There was a recent analysis at the global level which said that climate change is six times more damaging than some of the original estimates, and is costing the global GDP 12%, this is just the physical damage from climate change. So you know, the smart money people at some level can understand that this simply can't go on and continuing to stoke the market for more and more production and expansion of oil and gas is at some point a dead end. At least we can hope that the financial markets will see it that way.

CURWOOD: Pat Parenteau is an emeritus professor of law from Vermont Law School. Pat, thanks so much for taking the time with us again today,

PARENTEAU: And thank you, Steve, good to be with you.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “Lee Zeldin, Trump’s EPA Pick, Brings a Moderate Face to a Radical Game Plan”

- ABC News | “Reviewing Trump EPA Admin Nominee Zeldin’s Environmental Record”

- E&E News | “Trump’s DOE Pick Cements Fossil Fuel Focus”

- The Guardian | “Environmental Groups Alarmed as Doug Burgum Picked for US Interior Secretary”

- Inside Climate News | “Trump’s Top Staff Choices Could Have Far-Reaching Consequences for the Climate”

[MUSIC: Barefoot, “Arica” by Barefoot on Gardens of Eden, Putumayo World Music]

DOERING: Just ahead, President-elect Trump wants to gut the Inflation Reduction Act, but many benefits are going to red states. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Pinetop Perkins with Ann Rabson, “Careless Love” on Ladies Man, M.C. Records]

Biden Climate Cash in Jeopardy

President-elect Trump has expressed interest in pulling back the Inflation Reduction Act. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act has already doled out over $60 billion dollars in grants for thousands of climate projects across the country. And that doesn’t include even larger amounts of federal support in the form of loan guarantees and generous tax credits. Many of the projects funded by the IRA are focused on environmental justice communities that are disproportionately burdened by climate impacts. But President-elect Trump has vowed to dismantle the IRA and as the Biden-Harris Administration winds down, some communities are concerned about the fate of their climate funding. Jillian Blanchard is Director of the Climate Change and Environmental Justice Program at Lawyers for Good Government, and she offered her assessment of the situation to our colleague Aynsley O’Neill.

O'NEILL: So through the Inflation Reduction Act, the Biden administration rolled out a lot of money for domestic clean energy production and also for environmental justice communities. And from what I understand, you've been working with many of the communities that have received funding, you know, from day one. So please paint a picture for us. What do some of these environmental justice projects look like on the ground? You know, what kind of impacts are they having in their community?

BLANCHARD: Absolutely, yeah. We are working with cities and communities across the country and across the political spectrum to take advantage of the Inflation Reduction Act. And in fact, ironically, many of the benefits are going into red states. In fact, a majority of the funding under the Inflation Reduction Act, through tax credits as well as through grant programs, are going into red communities in red states. One example is some funding that will be going both through solar for all, as well as the tax credits under the Inflation Reduction Act into a micro grid project in Gary, Indiana that will benefit hundreds of thousands of underserved people on the ground in a very, very red state. In addition, we're working with a community in Toledo, Ohio, to build an eco village that will benefit underserved communities. It will also take advantage of tax credits that are available for EV infrastructure and solar. It will provide climate resilience hubs for the community to be able to go to in the event of a power outage. These are significant benefits and projects that are only made possible because of the inflation Reduction Act.

O'NEILL: Jillian, to what extent will those funds be protected as the country transitions to a second Trump presidency?

It would require an act of Congress to amend the Inflation Reduction Act. (Photo: Daniel Mannerich, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND)

BLANCHARD: It's an excellent question, Aynsley, and one that many organizations like ours are focused on right now because of the power and benefits under the Inflation Reduction Act. The answer depends on the program under the Inflation Reduction Act, and it depends on what level of disbursement the funds are actually in, if they've been announced, if they've been awarded, if they've been obligated, and ultimately, if they've been spent, they are more protected than those that are earlier in the process. However, we don't expect a Trump 2.0 to follow any industry norms. So we've already seen in the Washington Post an article suggesting that he intends to work with Elon Musk to amend the Impoundment Control Act, which serves as a very important protection to keep the power of the purse with Congress, not with the President, and if that action is successful, then a Trump 2.0 would have fairly unfettered discretion to be able to claw back funding under the Inflation Reduction Act.

O'NEILL: Now, Jillian, when we're talking about a sort of rollback of the Inflation Reduction Act, to what extent would that be able to be rolled back in just one fell swoop?

BLANCHARD: Right, it's a good question. It would not be rolled back in one fell swoop. First and foremost, of course, it would take an act of Congress to even amend the Inflation Reduction Act, which is going to require both houses and the presidency, but also there's some incredibly popular aspects of the Inflation Reduction Act, some aspects that even promote oil and gas projects and expedite permitting that many Republicans would not want to see repealed. So if there was a change, it would likely be a piecemeal approach where they would try to carve up different pieces of the Inflation Reduction Act that they deem less popular to the Republican side of the House.

O'NEILL: And how might these communities ensure that they sort of lock in those funds as quickly as possible? You know, what are the actionable steps that can be taken here?

The Inflation Reduction Act is benefiting communities in blue, red, and purple states. The IRA is helping create a microgrid in Gary, Indiana, a state led by Republicans. (Photo: Flickr, Paul Sableman, CC BY 2.0)

BLANCHARD: Well, it depends, again, on the program that they're taking advantage of under the Inflation Reduction Act. If, for example, they are planning to use tax credits, they can finish their projects and file for those tax credits as quickly as possible to be able to lock in those benefits. Like the Affordable Care Act, it's a lot harder to change a law when people are receiving actual checks in blue districts, red districts and purple districts. So taking advantage of those tax credits, and our organization L4GG, is helping cities and communities across the country do that. In addition for those grant awardees through things like Community Change Grants or Solar For All, it will be very important for them to finalize their contracts, set themselves up for good compliance under their contracts, and in compliance with their contracts, start spending down that funding as quickly as possible under the terms and conditions allowed.

O'NEILL: Jillian, how are political leaders in red states reacting to the possibility of the Inflation Reduction Act being pulled back?

In the summer of 2024, 18 House republicans, led by Andrew Garbarino (R-N.Y.) wrote a letter to Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) asking him not to cut clean energy tax credits set up by the IRA. (Photo: Franmarie Metzler, House Creative Services, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BLANCHARD: Well, I think that Republicans are seeing some of the benefits. In fact, 18 different Republicans have signed a letter saying that they want explicit pieces of the Inflation Reduction Act to stay in place. But that's why we wouldn't likely see any kind of a repeal of the Inflation Reduction Act whole cloth. In fact, it would likely be that different pieces of it would attempt to be carved out, particularly those that focus on environmental justice and those that focus on actually tackling the climate crisis.

O'NEILL: And Jillian, what would the consequences be if this funding gets taken away?

BLANCHARD: Oh, there would be significant consequences across the entire country. If the Inflation Reduction Act is clawed back, not only will we go years backwards in our push to tackle the climate crisis, but there will be many communities and many jurisdictions, including many Republican jurisdictions, that suffer grave economic consequences because they've invested in and taken loans out based on their guarantee that they would receive this funding under the Inflation Reduction Act.

O'NEILL: So even with the concern about individual programs being rolled back and concerns about losing funding, what gives you hope with the idea of these programs moving forward?

Jillian Blanchard is Director of the Climate Change and Environmental Justice Program at Lawyers for Good Government. (Photo: Lance Blanchard)

BLANCHARD: What gives me hope is that a lot of the money has already been obligated, meaning that it has already not only been announced, but that contracts have been signed, and some of the money has already gone out the door. And what that means as well on the ground is that people are realizing the benefits of this funding, they're seeing it in their community, and that's much more likely to retain the popularity of the Inflation Reduction Act and hopefully be able to preserve it in the future. I'm also seeing that a lot of the funding is going to states and to local governments where the fight for climate and equity is going to be focused for the next four years, because we're not going to take this backwards. We are going to move forward. This is a crisis that all of us are dealing with, and the number one way to move it forward is with respect to state and local protections. In fact, our climate change and environmental justice program at Lawyers for Good Government was formed the day after the previous Trump administration announced withdrawal from the Paris Accord with a focus and a goal to work with state and local leaders to push and meet and beat Paris Accord goals in the absence of federal leadership. We will do that again, and we will continue to push that forward and now, thanks to the Biden Harris agenda and the Inflation Reduction Act, we have a lot of that funding that's already gone down to these states and local governments to make a real difference.

DOERING: That’s Jillian Blanchard, climate and environmental justice director at Lawyers for Good Government speaking with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill.

Related links:

- The White House | “Inflation Reduction Act Guidebook”

- Read more about Lawyers for Good Government

- The Washington Post | “Trump Aides Explore Plans to Boost Musk Effort by Wresting Control from Congress”

[MUSIC: Victor Wooten, “Funky D” by Victor Wooten/Improvised, Live Studio Session on KNKX Public Radio, Seattle & Tacoma, Washington]

Shiitake Mushroom Harvest

The inoculated log behind Jenni’s compost bin. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

DOERING: So, Steve, you may remember that in September of last year, Living on Earth’s very own Aynsley O’Neill and I spent some time inoculating a log with shiitake mushroom spawn.

CURWOOD: Right, you wanted to grow a few in your backyard garden. A year or so later, any updates?

DOERING: Well, we did successfully grow and harvest some mushrooms…

CURWOOD: You sound a little uncertain there, Jenni.

DOERING: Well, okay, it all started out fine. I invited Aynsley over when I first noticed that they had sprouted up…

[OUTDOOR AMBI]

DOERING: So it's back here behind my black plastic compost bin. Look at that.

O'NEILL: Whoa. Okay, those are, those are really big. I didn't realize they were that big.

DOERING: Yeah. I mean, like five inches across, maybe?

O'NEILL: Yeah like, like the palm of your hand.

CURWOOD: Uh, Jenni, if I’m seeing a shiitake mushroom in a grocery store, I don’t think it’s usually grown to that size.

DOERING: Yeah, there’s a chance we left it a little too long. They also were looking a little dried out…

[OUTDOOR AMBI]

DOERING: Now, some of this has a little bit of, like, brown on the gills. I think that might mean they're starting to get older, but we can still try these. I think we can still cook them up,

O'NEILL: And I think we should, you know, definitely make sure to identify the mushrooms before we eat them anyway, just in case.

DOERING: Yeah, yeah, something else. Yeah, you know, like, you don't want, like, a death cap growing on this log, yeah. And then you, you're like, oh, dinner!

O'NEILL: Yeah, we'll head in and do some research.

CURWOOD: Right, well of course you really have to be careful with identification when foraging mushrooms out and about, but I suppose you’d still want to be cautious with this backyard crop. I mean, these should be shiitakes, but what if something else snuck into the log?

Wild shiitakes growing on a log. (Photo: Ezonokuma, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

DOERING: Right, a backyard isn’t a sterile environment. We gave those shiitakes a head start so they likely would have outcompeted anything else, but it’s always good to check. Especially if you’re going to be cooking them up like we were!

CURWOOD: And, Jenni, what are your culinary plans here? There are so many ways to prepare mushrooms, what are you thinking?

DOERING: Well, we didn’t want to complicate the flavor too much, so we stuck with a very simple recipe.

[KITCHEN AMBI]

DOERING: I think we can cook them up with some onion, green onion, salt and pepper, and see how they taste.

O’NEILL: Delish! Let’s go!

DOERING: I'll do some chopping over here. So bite sized pieces for the mushrooms, we're gonna dice the onion, add them to a pan with a little bit of oil and sauté. Okay.

[CHOPPING SFX]

O'NEILL: Our ratios might be a little off. That's fine.

DOERING: Yeah.

O’NEILL: Onion, scallion, mushrooms, it's all tasty. And part of our goal is to have the taste of the mushrooms shine through.

[SIZZLING SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: Mm mm, that does sound tasty.

DOERING: Oh yeah, there was just one problem though…

[KITCHEN AMBI]

[SAUTEEING SFX]

DOERING: Wait, were we supposed to, like, double check and research these?

[SAUTEEING SFX]

CURWOOD: Oh, Jenni, say it ain’t so!

DOERING: That’s right, Steve, we got so distracted by cooking that we almost forgot to finish our research!

CURWOOD: That could have been real trouble…

DOERING: Luckily, there aren’t too many poisonous mushrooms that look like shiitakes. But we weren’t taking any chances!

The harvested shiitakes. (Photo: Aynsley O’Neill)

CURWOOD: How did you do your sleuthing?

DOERING: So, we tried a few different avenues. First, we reached out to the customer service desk for the company where I got the starter kit.

[ROOM AMBI]

DOERING: All right, so Tony Lee from North Spore got back to me and said, I'm happy to help with the identification. So they said, Can you provide pictures of the topside underside and habitat?

O'NEILL: Oh, we have all of those.

DOERING: We've got all of that. So I'm attaching these.

O'NEILL: I love picturing somebody sitting at their desk with a head set on with a big book of my ecology next to them, ready to identify at any given moment.

DOERING: All right, moment of truth. Thanks for the inquiry. Based on the information provided, it looks like you have some shiitakes. With photos alone, though I can't provide 100% certainty, it's important for you to consult other credible sources….

CURWOOD: Hmm. That only sounds a little reassuring.

DOERING: Right, so after that, we did some online research on some mushroom identification sites and sent pictures to some amateur mycologist friends. And I’m happy to report that everyone came to the same conclusion!

[ROOM AMBI]

DOERING: So a couple of people confirmed they do look like shitakes. So what do you think? Do you feel safe trying these, Aynsley?

O’NEILL: Let's give them a go!

DOERING: Let's give them a go. So, I'm tasting this for the first time. Want to see if the seasoning is right. So here we go.

O'NEILL: Hmm. It smells really good, is what I'll say.

DOERING: Yeah, that's nice. It's earthy, nice. I think I'm just gonna add a little more seasoning.

[PEPPER MILL SFX]

Shiitakes for sale at a market, with a very uniform size and shape. (Photo: Peachyeung316, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

O'NEILL: A pinch more salt.

DOERING: Okay.

O'NEILL: Let's dish it up.

DOERING: Yeah, so a little bit of scallion, delicious.

O'NEILL: Fresh scallions, too. From the garden.

DOERING: Yes, straight from the garden. Bon appetit. Cheers, cheers.

[CLINK SFX]

O'NEILL: Oh, that's good.

DOERING: Mm, hmm, this would be really good in a stir fry, or, like in ramen.

O'NEILL: Yes!

DOERING: I could also use the rest in some pasta, like, for sure, parmesan and some butter, you know, something simple.

O'NEILL: Or, you know, hibachi or barbecue, you know, some sort of grilling things like that. Super good, yum. Really nice, really cool. I mean, you're already a gardener, so you grow your own stuff all the time, but first crop of mushrooms. How's that?

DOERING: Yeah, this is exciting. This is, this is a step up, I guess, but it's also, it really wasn't that hard. There was just some setup. There was some drilling, and I let that log sit there for a year, you know, like it just hung out behind the compost.

O'NEILL: Yeah, you really set it and forget it the way they say.

DOERING: And we should be getting some more of these throughout the next few years. So lots to look forward to.

O'NEILL: You'll have to bring some into the office.

DOERING: I think I will.

CURWOOD: Well, I am in full agreement – please bring some in for the whole crew to try next harvest!

DOERING: Copy that, Steve!

Related links:

- Listen to LOE’s previous coverage of a backyard mushroom kit here

- Learn more about the process of growing mushrooms on a log

[MUSIC: Al Petteway and Amy White, “Riding the River” on Racing Hearts, Fairewood Studios]

CURWOOD: Coming up, Robin Wall Kimmerer on sharing and gratitude for the abundance of Earth. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Eugene Friesen, “Remembering You” on Arms Around You, by Eugene Friesen, Living Music]

Robin Wall Kimmerer on The Serviceberry

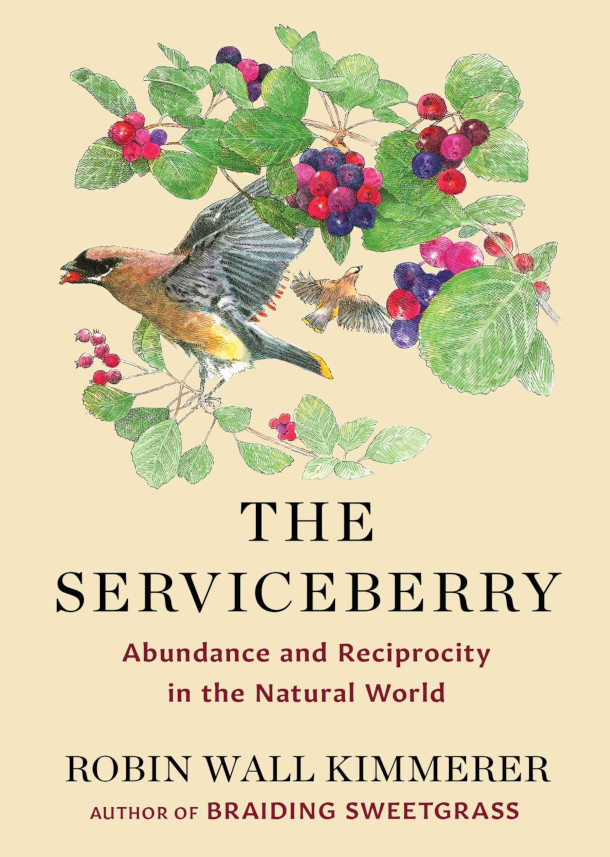

The cover of The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer beautifully encapsulates the book's themes of nature’s abundance and reciprocity. (Photo: Courtesy of Robin Wall Kimmerer)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

You’ve seen the prices at the grocery store, maybe even cringed a little. Could a dozen eggs really cost that much? And $7 for a gallon of organic milk? That’s the capitalist society we live in, where we pay the current market value. But for most of human history, no money changed hands and even bartering is thought to be less than ten thousand years old. Instead, we got what we needed and took care of each other thanks to gift economies. Rather than selling goods and services and accumulating wealth, in a gift economy they are given freely in a web of reciprocity. Robin Wall Kimmerer is perhaps best known as the author of Braiding Sweetgrass, about living in a reciprocal relationship with other beings and the gifts of the Earth. And she’s back with a new book that continues her explorations of gift economies. It’s called The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World. Robin Wall Kimmerer is a member of the Citizen PotaWAtomi nation and professor of environmental biology at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, and she joins us now. Hi Robin and welcome to Living on Earth!

KIMMERER: Hi, Jenni, thanks for the invitation to join you.

DOERING: So what is a serviceberry, and why is it significant to you?

KIMMERER: A serviceberry is a beautiful genus of plants. It doesn't look like much. In fact, I tell my students, you can tell a serviceberry because it's kind of generic looking in that the leaves are just round, smooth, gray bark. But when it flowers and fruits, it's a whole different story. In the springtime, there's just a froth of white blossoms, and then in mid summer, it's just heavily laden with these red, juicy fruits. You can mostly find it around edges of water, edges of trails. It's an ecotone species that kind of likes the forest edge.

DOERING: And it sounds like it brings this abundance in season, when these berries are ripe, all kinds of animals and people, including yourself, enjoy these berries. So what does that abundance of serviceberries lead to?

KIMMERER: Well, the abundance of serviceberries leads to an abundance of life all around because, for example, in the early spring, there's a whole group of bees that rely entirely on those early spring flowers, right? So it's feeding the pollinator community. And then later, when the berries start to ripen, oh, you can find a serviceberry tree, because of all the birds, they are all just gathering there, and they're so noisy. I use them for prospecting. That's how I find a serviceberry tree is I listen for the birds, so it's feeding that whole community as well. You know, those are the obvious ways that it's engaged, but it's also an important host for lots of different larvae of butterflies and the whole food web that grows around this tree.

DOERING: And you yourself describe in this book, harvesting, putting those berries into a pail, and then being able to share that abundance with your neighbors.

KIMMERER: That's right, they are so abundant that on my neighbor's farm, where they plant the Western variety of serviceberry known as saskatoons, they are just an exemplar of abundance. You can just pick them by the handful.

The serviceberry is a small, sweet fruit, deep purple or reddish-blue when ripe, with a flavor resembling a mix of blueberries and almonds. It's rich in nutrients and perfect for fresh eating, baking, or preserves. (Photo by Melissa McMaster, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: And you can turn them into a pie?

KIMMERER: Oh, they make a good pie. They make good jam, good syrup. But you know, traditionally, a lot of native cultures, particularly Western cultures, used it's the source of pemmican. It's the major fruit for pemmican. So the berries would be dried and pounded into this really super food. The berries are really rich in antioxidants and vitamin C. So it was an excellent choice to mix into the original energy bars, which were pemmican.

DOERING: And, pemmican, remind me is that a mix of berries and meat?

KIMMERER: It is, yeah, the berries are dried and pounded, and elk or venison is also dried and pounded, and then the whole thing is bound together with rendered fat. So it is quite literally the original energy bar, and our people used it for travel food and for trade, etc. It was a really important way to store excess calories.

DOERING: Tell me about the connection here between this idea of a gift economy and the way that resources are shared in the natural world. Could you maybe trace the path of a serviceberry for us? Maybe the berry itself falls to the ground or gets eaten by a bird, and what happens next?

A portrait of Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of The Serviceberry, reflecting her deep connection to nature and ecological knowledge. (Photo: The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation)

KIMMERER: Well, I think it's important to preface that by talking about what I mean by gift. And a gift in my thinking, and this reflects a lot of ancestral teachings. A gift is something that we have not earned, and yet it comes to us, someone bestows it upon you. So let's follow the thread that you suggest, Jenni, of the growth of a serviceberry, the sun. The sun is the energy that animates all of it, and so all of that sunshine, through photosynthesis, turns into the body of the serviceberry. One could argue that the sun, the sun's energy, is a gift we have not earned it, and yet it comes. But that gift of photosynthesis is then shared with others. It's shared with the larvae of those caterpillars that are eating the leaves. It's shared in the abundance of fruits that the robins and the cedar waxwings and the blackbirds are all coming to feast on. The gift is shared. It's passed on. And then, of course, those birds that are splattering bird poop all over the ground, all of that nitrogen, right, is feeding the food web below ground and building soil. The fox that comes and snatches one of those robins off the ground while it's all full of berries, the gift stays in motion. And so if we start with the premise that what life produces for us is a gift, it's all a gift economy.

DOERING: In the book, you quote an indigenous Brazilian hunter saying, "Store my meat? I store my meat in the belly of my brother." Can you tell me the story of that quote?

The serviceberry fruit, sweet and tart, supports pollinators and birds, playing a vital role in ecosystems. (Photo: Unsplash, public domain)

KIMMERER: Yes, that quote, that story that was shared by an anthropologist, linguist working with Amazonian indigenous peoples, is at the heart of what we understand to be a gift economy. In this story, the hunter had been successful that day and came back with a really sizable animal. And so the anthropologist linguist was talking with them and saying, "Well, how are you going to store the meat? Are you going to dry it or salt it? What will you do to store the meat?" And he reports the astonishment of the hunter, saying, "Store my meat. Why would I do that?" And so he asks again, and he said, "Well, no, I don't store my meat. I store my meat in the belly of my brother." Meaning he wasn't going to hold on to and accumulate this bonus, this surplus of meat. He was going to have a feast. He was going to invite his neighbors, his friends, his extended family, all to come and benefit from what the forest had provided him in the form of game. And the anthropologist was astonished because that breaks all the rules of Western economics. Doesn't it? That says, "Well, you should hold on to that for yourself. You should store it so that when the hungry time comes, as it inevitably does, you'll have food security." But essentially, the lesson taught by that story is there are other ways to have material security, food security, and that is through relationship. That hunter was saying, when I feed my neighbors, when I feed my community, they're going to feed me when their nets are full of fish, they're going to invite me to a feast if I need their help, we've established good relationships of trust and kinship, so they'll take care of me, because I'm taking care of them. And that is the heart of a gift economy. No money is exchanged. The gift stays in motion. It creates this network of relationships that create the kind of material security that market economics is designed to produce.

DOERING: And in our own lives, what advice do you have for centering gift economies, participating in those and reciprocity in our lives while also living in this modern world, this complex world?

Before it bears fruit, the serviceberry plant is characterized by its delicate white flowers in early spring, which attract pollinators. (Photo: Unsplash, public domain)

KIMMERER: Well, the book is full of examples of micro scale gift economies. Some of the ones that seem most appropriate to think about in a time of climate crisis. What is it that's driving the climate crisis? It's hyper consumption, overconsumption, and gift economies suggest. You know what? We don't all need to own everything that we need in life. We don't need to each go out and buy a lawnmower. We don't. We need, perhaps one for the neighborhood. And those kinds of neighborly sharing help to stem hyper consumption, but you also create a web of mutual relationship, which I think as human people, particularly in an industrialized society, we crave. We crave that sense of belonging, of being known, of being needed in our communities. So that's how I think about the role of gift economies as a sharing economy that produces abundance without market regulation. And so I think gift economies can live in coexistence with the dominant model of economics, if we encourage them. And I don't want in any way this idea of trying to promulgate small, highly localized gift economies to in anyway excuse us from rethinking capitalism and damage associated with it. In the book, I talk quite a lot about the ethical jeopardy of extractive systems and the cost that that has in the well being of the planet, and while we could celebrate and cultivate small scale gift economies, that doesn't mean we aren't still complicit with this larger system that we need to seriously rethink.

DOERING: Can you describe for me scaling up this gift economy idea and how we can kind of work with this complex, global, interconnected world that we have, and integrate some more of this gift economy thinking into that system?

KIMMERER: You know, I began looking for gift economies in modern society after having learned about them from both ancestral and contemporary indigenous societies, and I found them everywhere, once you kind of know what to look for. One of the examples that I like to start with is, you know, when you read a good book, you want to pass it on to a friend. You don't sell that book to your friend. You give it to them. There it is a tiny, little gift economy. But how does that scale up? Well, in my neighborhood, we have little free libraries where people say, oh, let's leave our books here to share with one another. That's a gift economy. I think about public libraries as gift economies. We don't own the books. That's the idea. We have abundance of literature because we share. So that continuum from the giving a book to a friend, to little free libraries to public libraries, gives us a hint at what gift economies can look like. And at a larger scale, the way that we use our financial resources to invest in commons. Common resources, like libraries, offers us an opening as well. What about things like common lands of parks and trails and water? Those are things we don't each of us own. We care for them in common. We enjoy them in common. So gift economies are also an invitation to the economy of the commons, rather than of private property and individual ownership.

DOERING: Before you go, Robin, in this season of harvest, how does giving thanks connect with abundance and reciprocity?

KIMMERER: Gratitude is such an important human response to the abundance of the world and deep gratitude. No, I don't mean just like that polite toss off thank you. I mean the kind of gratitude where you recognize that your life is totally dependent upon the lives of other beings that you would not exist without water or those berries or that medicine, that kind of deep gratitude that allows us to look at the world of abundance and feel as if you have everything that you need. Let's be clear, everything that I need might be quite different than everything that I want. But everything that I need, I have and is provided for me as a gift from Mother Earth. It also makes you feel as if you have everything, and so why do you need to buy anything else? It creates a sense of sufficiency and enoughness that puts the brakes on consumption. I believe eco psychologists have demonstrated that people who practice gratitude consume less than people who don't. To think about the world as gift is to think about the world not as objects that belong to us, but as stories. That shirt that you might want to buy, it's not just as an object, is it? It's the product of many hands, and it has consequences. It has costs. And so I think one of the most important things we can do as consumers is to really think about the stories associated with those objects. Was that fiber in the shirt that you're interested in, is it recycled? Is it part of a circular economy, or is it part of an extractive economy? And when we see the world as gift, we see that whole story of knowing where everything came from, and then that's what helps something be a gift, not a commodity is we know all the relationships that are associated with it. But that same attention to the story of an object allows us to decide whether we're going to buy it or not. Are we going to participate in a dishonorable harvest, or are we only going to purchase those things which safeguard life, make life better?

DOERING: Robin Wall Kimmerer is the author of The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World and other books. Thank you so much, Robin.

KIMMERER: Thank you.

Related links:

- Purchase a copy of The Serviceberry (Affiliate link supports Living on Earth and local bookstores)

- Discover insightful reader reviews and more about The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer

- Read The Guardian’s review of Kimmerer’s work, delving into the book’s exploration of ecological wisdom and reciprocity in nature

- Learn about the fascinating Serviceberry plant

[MUSIC: Andrew Gialanella, “Ease” Single, Andrew Gialanella]

Earth Prayer

Joe Bruchac’s poem is dedicated to Mother Earth. (Photo: Jonathan Kemper, Unsplash)

CURWOOD: On the line now from Porter Corners, New York is Joe Bruchac, a Nulhegan Abenaki storyteller and poet who’s here with his reflection on gratitude for the gifts of the Earth. Joe, good to talk to you again. How you doing?

BRUCHAC: Oh, I'm good, kwai kwai nidôbak, hello my friend.

CURWOOD: And what do you have for us today?

BRUCHAC: I have an original poem that I wrote. It's based on traditions among the Haudenosaunee the Iroquois people, and the Wabanaki, my own people, of giving thanks and acknowledgement for the gifts that we often take for granted that are all around us. It's called Earth prayer.

© 2023 Joe Bruchac

EARTH PRAYER (Adapted from Haudenosaunee and Wabanaki traditions)

Because this Earth is our first mother

we say Ktsi Wliwini, mina ta mina--

Great Thanks, again and again.

Because all our ancestors could see

the rain that falls, the air we breathe

the healing waters, the giving stones

our mother’s blood, our mother’s bones

are gifts we have been given.

Joseph Bruchac is an author of more than 120 books for children and a member of the Nulhegan Abenaki Nation. (Photo: Courtesy of Joseph Bruchac)

It is from this Earth that all our lives,

those who came before us, those yet to come

like the seeds that sprout with each new spring

have grown, have grown, have grown.

And what does this Earth ask of us?

All that it asks is that we never

take too much, always remember

to give back in equal measure

for those gifts we may take for granted.

And also remember that we must

walk with care, always show kindness

to all those now here with us

sharing gifts of life and light,

never forget those who share our breath

two-legged, four-legged, those with wings.

those who swim or dig into the soil,

the grass, the trees, all living things

from the greatest to those too small

to see are also related, one and all,

Wli dogo wongan, all our relations.

So, as we continue on this circle

which has no beginning and no end

let us all say to our Mother Earth

Ktsi Wliwini, mina ta mina--

Great Thanks, again and again.

CURWOOD: Thank you, Joe Bruchac.

BRUCHAC: Doc hug we don't mention it. You are very welcome.

Related links:

- Storyteller Joe Bruchac’s Website

- More on the Nulhegan Abenaki Nation

[MUSIC: Andrew Gialanella, “Reality” Single, Andrew Gialanella]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Josh Croom, Daniela FAH-ria, “Mehek” Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, and El Wilson.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And we always welcome your feedback at comments at loe dot org. I’m Jenni Doering

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth