Under Alien Skies: A Sightseer's Guide to the Universe

Air Date: Week of November 29, 2024

Philip Plait’s 2023 book, Under Alien Skies: A Sightseer’s Guide to the Universe, explains what it would be like to explore outer space. (Photo: W. W. Norton)

Astronomer Philip Plait wondered what it would be like to walk on Mars, fall into a black hole, or fly through a nebula, so he wrote a book, Under Alien Skies: A Sightseer’s Guide to the Universe. He joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to reveal the strange colors of a sunset on Mars, what it’s like on a planet orbiting binary stars, the unique challenges of landing on an asteroid, and more.

Transcript

O’NEILL: From Star Trek to Star Wars to Treasure Planet, fictional portrayals of outer space are everywhere. But if you’re wondering what walking on Mars, flying through a nebula, or falling into a black hole would actually be like… that’s better left to science fact than science fiction. Luckily, one astronomer has written a book all about these strange realities. Under Alien Skies: A Sightseer’s Guide to the Universe takes readers on a cosmic journey while teaching them what the universe outside our little blue planet is really like. Joining us now is author Philip Plait, former member of NASA’s Hubble Telescope team, and writer of the newsletter called Bad Astronomy. Phil, welcome to Living on Earth!

PLAIT: Thank you. It's nice to... well, it's nice to live on Earth. So thanks.

O'NEILL: So Phil, Under Alien Skies has these really engaging descriptions that sort of imagine what it would be like to travel to various places in outer space. Could you please read from the first two paragraphs or so from the chapter on Mars?

PLAIT: Yeah, sure. I'd be happy to. “You're out of bed early, suited up and out the airlock before anyone else is awake. It's not strictly protocol. The commander says you should have a buddy with you when out on the surface when possible. But you love seeing the landscape as the sun rises. You walk out a ways from the hab module until the view to the east is clear. Facing west first, though, you watch as the black sky above you turns butterscotch in a slow wave moving down toward the horizon. As you turn to face east, the sun appears, and the sky around it turns a shade of pale blue. Even so, there are still stars visible. The thin air doesn't scatter enough light to entirely block them, even when the sun is up. One stands out though, a blue green jewel shining a few degrees above the sun. That's home you think, Earth some 50 million miles sunward.”

O'NEILL: And now these sections walk the line between non-fiction and sci-fi. What made you decide to incorporate little fictional scenes into this science book?

PLAIT: Oh, that's easy. I'm a dork.

O'NEILL: You're in good company.

PLAIT: Yeah, there are millions of us. For me, science and science fiction are both ways that we describe reality. And in science fiction, we use our imagination, right? We have science that we don't necessarily have yet, whereas in actual science, we're using our imagination to try to imagine what these things are like that we're describing. You know, in astronomy, you've got some planet that we've discovered, and it's orbiting some star, and we know enough about the star and where the planet is to start guessing intelligently about what conditions would be like there. And by using our imagination, we can fill in some of those gaps. And the beauty of that in science is it gives you an idea of what you might want to look into next. Like, I wonder if liquid water could exist on this planet. Well, you know, it depends on the atmosphere. Well, what kind of atmosphere would it have? And so it's all of this imagination going into it. So for me to write a book about these places, starting each one off with a little science fiction vignette, an anecdote, that is me holding your hand and showing you all of these amazing places that astronomers, we live our lives in. We just can't actually go there typically.

Phil Plait is also the author of Death from the Skies and Bad Astronomy. (Photo: Marcella Setter)

O'NEILL: Well, one aspect that I really enjoy is that you incorporate, of course, the science fiction, the science fact, but you also go into the history of astronomy. You talk about how we found out what we know now. Tell us a little bit more about the history of astronomy that you put into this book.

PLAIT: That was another easy decision because something that really bugs me about the way people think of science is they think of it as like a compendium of facts. It is a dictionary that you open up to what our star is made of, and you look it up and it's, oh, hydrogen, helium, blah, blah, blah. And how do you know that? You read it in a book, but how do you know the book's right? So by throwing in the history of how we learn some of this stuff, it makes it more like what science really is, and that is a process. Science is not something you look up. It is something that learns and grows, and it's almost like its own organism. It's almost like a living thing. Science doesn't just grow linearly. It's not just we learn this, then we learn this, and then we learn that. It's not like that. And so it's kind of fun to put stuff in the book that says, you know, hey, this was a matter of some debate, and then it turns out this person was right, or they were both wrong, or something like that. It makes it more human. I talk about how the first planets around other stars were discovered. It's one of my favorite stories in all of science. Basically, some scientists had announced that they had found a planet orbiting another star, and then turns out they were wrong. They had made a mistake in the way they observed their data. And they had to stand up in front of a group of their peers and say, We messed up. And then the next team of scientists walks up to the microphone and said, Yeah, we actually have discovered a planet. We didn't do the same thing they did, and our data are good. And yeah, they were right.

O'NEILL: Wow.

PLAIT: Literally, the next people to talk at that conference. You know, you couldn't write that in a TV show, but it really happened. And so I just, I love it. I just love stuff like that.

O'NEILL: And one of the amazing facts that we learned via that scientific process is that Mars has a sort of color flipped version of Earth's sky. So during the day, the Martian sky is a sort of orangey red, but then it turns blue at sunrise and sunset. Why is that the way it is?

PLAIT: Right, it's the opposite of Earth. During the day, our sky is blue, and then when the sun sets, the sun kind of turns red, and the sky around it turns red. And for us here, it just has to do with the way Earth's atmosphere scatters blue light. So red light can just pass right through our atmosphere, but the blue light from the Sun bounces off these molecules in our atmosphere, and then can come at you at any random direction. So anywhere you look in the sky, you see blue, but you only see red when you're looking toward the sun. On Mars, it's the opposite. Mars has all of this dust in the atmosphere that is heavily laden with rust. It's iron oxide, different kinds of iron oxide, but it's rust. And so you know, you know what the color of rust looks like. It's that orangey hue. And so during the day, the sunlight passing through Mars's atmosphere is lighting this dust up. And so it looks orange. However, near the Sun, there is another effect that takes place, and it has to do with the way light is scattered. But that blue light is scattered toward you. And so when you are looking near the sun, the sky looks blue. I mean, even during the day, even at noon, but at sunset, that effect is magnified a lot. And so the sunsets and the sunrises on Mars are going to look blue near the sun. So it's the exact opposite of Earth, even though it has an atmosphere, and it's kind of Earth-like and all this stuff, you wind up getting the exact opposite thing that you might expect. It reminds you that Mars is an alien world.

[MUSIC: Harry Gregson-Williams, “Making Water” on The Martian: Original Motion Picture Score, Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation]

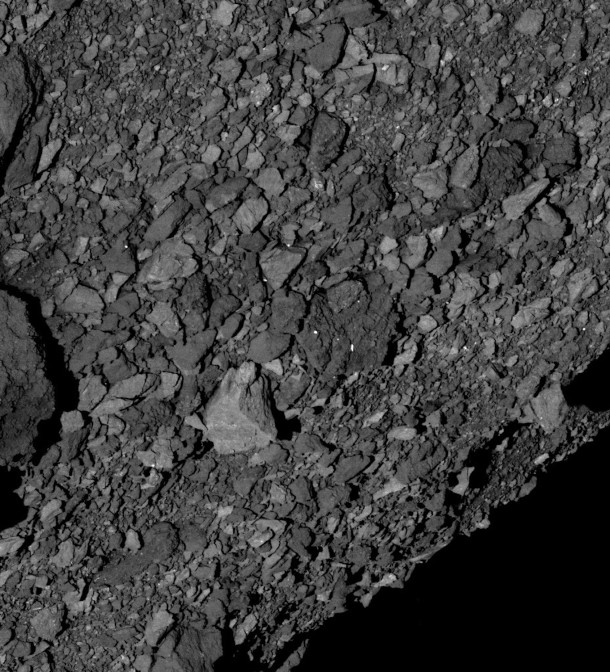

The chapter on asteroids was Plait’s favorite to write. Asteroids may look solid, but they are really just rubble piles held together by gravity. (Photo: NASA, public domain)

O’NEILL: In a moment, we’ll travel to other alien worlds with astronomer Philip Plait, who’s speaking with us about his book Under Alien Skies. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Harry Gregson-Williams, “Making Water” on The Martian: Original Motion Picture Score, Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Harry Gregson-Williams, “Sprouting Potatoes” on The Martian: Original Motion Picture Score, Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. We’re back with Phil Plait, astronomer and author of Under Alien Skies.

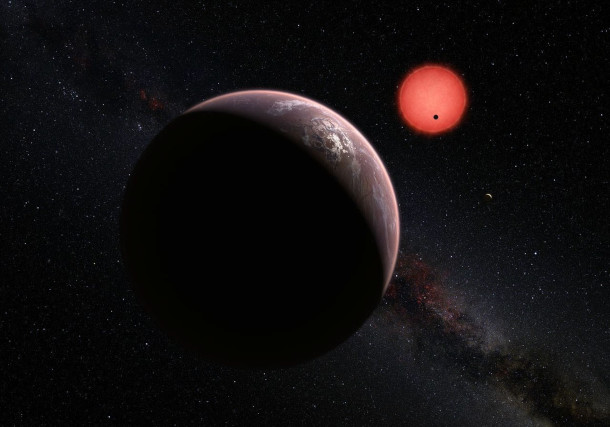

O'NEILL: This book doesn't just cover places within our solar system. It also goes into detail about what it would be like to be outside of our little cosmic neighborhood, and it includes a section about a planet that orbits two suns. Tell me more about that chapter and about the idea of this binary star system.

PLAIT: Right, how could I not write about this? It's so cool. I mean, we all remember Luke Skywalker standing at sunset on Tatooine with his leg on the rock and the wind whistling through his hair as these two suns set on the horizon. That's an iconic scene, but it's also kind of correct. They kind of got that right. Tatooine orbits two stars that are both kind of like the sun, and it's on a, it's what's called a circum binary orbit, which means it goes around both stars. You can also have binary stars, two stars that orbit each other and have a planet only orbiting one of them, and the way the sky looks in these circumstances are different, especially if you orbit one star and the other one is orbiting much farther out. There are times of the year when it's always bright out. You've always got a star up in the sky. The star you're orbiting sets, but this other star farther out is still up in the sky, and it would be very bright, like brighter than the full moon, so you'd still be able to go out and do things at night. Other times of the year, when they're lined up and both in the sky near each other, they would set and it's dark, just like it is on Earth. So you'd have these really weird seasons where night time changes quite a bit. And if you orbit both, it's also very strange, because you have two stars in the sky, they'll cast two shadows, kind of, sort of. I exaggerated that a little bit for the book, that you would see two shadows. It's not that obvious. However, if these stars orbit each other very closely together, as they would have to, if you orbit both, sometimes one will pass in front of the other one. You'll have essentially an eclipse, except you're not blocking a star with the moon. You're blocking a star with another star. So instead of two stars in your sky, now you have one, and the temperatures will cool off very rapidly. And so I had a lot of fun extrapolating what life would be like. What would it be like to live on a planet where sometimes it doesn't get dark at night and other times it gets very cold suddenly for an hour or so during the day, even in the middle of summer? It was very strange to think about this stuff, but a lot of fun.

TRAPPIST-1 is a planet that orbits a star other than our own sun. (Photo: NASA, public domain)

O'NEILL: Now, when the book is describing places outside our solar system, it does talk about how we may never travel to these distant locations, because it is, as far as we know, probably impossible to travel faster than the speed of light. What does this mean for the future of space exploration? And also, what does it mean for the possibility of finding extraterrestrial life out there?

PLAIT: Well, that's a big question. I was very careful in the book to use as much current science as I could, and when I can't, I'm very clear about that. So when we leave the solar system in the second half of the book, I make it clear. It's like, look, we don't have faster than light ships, but let's pretend we do, and we can just hop on board and travel to a globular cluster, a cluster with a million stars in it, and be on a planet that's orbiting one of these stars. But if we can't do that, what does that mean? Well, the search for life on other worlds isn't limited to us boarding the USS Enterprise and heading off into the deep black. We're looking in a lot of ways. We're listening for radio signals from intelligent life. We're looking for what astronomers called bio signatures, which are signs of, say, oxygen or water in the atmospheres of planets orbiting other stars. You don't have to go to these places to maybe find life. There are maybe, maybe, maybe ways of detecting it, even from Earth. And we don't know, because we haven't done that yet. We have a lot of really good ideas. I mean, that was just a couple. There are dozens of ways that astronomers are looking for life on other planets, but it would have to be passive. In other words, it would have to come to us, these signals, whether it's intelligence signals or the signal of oxygen in the atmosphere, for example. That's just how it is. Unless somebody figures out how to make a warp drive, we're not going there anytime soon. It would take 100 years to get to the nearest star, more or less. We understand that there is technology that could travel at a decent fraction of the speed of light. But even then, it's 40, 50, years just to get to the nearest star. That's a lifetime. You better be absolutely sure you know what you're doing when you close that hatch and head off. And right now, we're just not there yet.

O'NEILL: And so, Phil, you got to write about some really incredible places. Which chapter was your favorite to write?

PLAIT: Oh, you can't ask an author that. It's like asking a parent who their favorite kid is.

O’NEILL: I know.

PLAIT: But in fact, typically what I would say is Saturn. I love Saturn. Everybody loves Saturn. If you've ever seen Saturn through a telescope, it is just phenomenal. You can see those rings. You can see moons orbiting it. And a lot of astronomers, myself included, will tell you, I got hooked when I was a kid because I saw Saturn through a telescope. And I show people Saturn through a telescope, and it's just so much fun to watch their faces. This wave of awe comes over them. They gasp, they laugh, they shout. They can't believe that it's real. And so writing about Saturn was amazing. And so that's the easy answer, and that's what I usually say. But I gotta say, writing about asteroids was a lot of fun. I'm fascinated by asteroids, these chunks of rock and metal that orbit the sun, most of them out between Mars and Jupiter, so pretty far from the earth. Most people think of asteroids as these giant rocks that can hit the earth, wipe out the dinosaurs, maybe give us a pretty bad day. But as scientific objects, these are the precursors of the planets. These were the building blocks that built up the planets, including Earth. And we didn't know that much about them when I was a kid, and I would watch TV shows, and there'd be a swarm of asteroids that would, you know, wipe out the ship or make them go off course, or whatever. And it turns out, it's not like that. There are millions of them out there, but they're spread way out. And they're not just like giant chunks of rock, like you'd expect, like a mountain. The smaller ones are actually like bundles of debris. They're like bags of rocks. We call them rubble piles. And it's like go to a construction site and see where they've dug up all the rocks out of the ground. It's kind of like that. They're just rocks held together by their own gravity. And it turns out it makes them pretty different. The rocks are so fragile on these things that if you picked one up, you could easily crush it with your hand. And so if you try to land on an asteroid, you could literally fall right through the surface and find yourself buried inside this thing. Be like jumping into a box filled with styrofoam peanuts. They just scatter everywhere, and you fall right in. That was so surprising to me, but we had a space probe that did that. It touched an asteroid, and if they hadn't backed it out of there, it would have sunk right in. And I think that surprised everybody.

Plait recommends looking at the sun to see sunspots, but only wearing appropriate eye protection like eclipse glasses. (Photo: Mamta Patel Nagaraja, NASA, public domain)

O'NEILL: So reading this book, in some ways, provides a sort of escape from the problems here on Earth. I mean, especially with that second person perspective, you really feel like you're out there on Pluto. But some might say that given issues like climate crisis and conflict around the world that we shouldn't prioritize space exploration and space science. How do you respond when people say things like that?

PLAIT: Well, I understand that attitude, but it's not looking at it the right way. It's an ill posed question, as we like to say. First of all, it's not a dichotomy. It's not like we're spending all this money on space. We should be spending it on Earth. In fact, NASA's budget is so small, it's less than half a percent of the federal budget. As an astronomer once said, if you were to take the budget of the United States as a $1 bill, and you cut the edge off where NASA's budget is. You wouldn't even hit the ink. It's very, very, very tiny amounts. So the amount we're spending on the military is vast compared to space exploration. So I'm not saying we don't need a military, but we spend the money on a lot of things, and spending it on space exploration... really, there are much larger things you could turn to to say, why are we spending money on this? But also we're spending that money not in space. It's not like we're launching rockets full of $20 bills and letting them go. We're spending that money here on Earth, and we are learning about Earth. We have problems here. But how do you think we study climate change? If you're worried about climate change, you should be wanting to spend more money on space exploration, because we look at Mars, we look at Jupiter, we look at Venus, we study what the weather is going on there, and that informs us on how the weather works on Earth. It's a very, very complex set of systems, and by studying how it works on these other planets, it informs us on how it works here.

PLAIT: So Phil, you're obviously an expert on space, but I'm guessing you didn't know every single fact in this book before you wrote it. So what was the research process like?

PLAIT: Yeah, I do have a passing familiarity with a lot of the topics in this book. Some of them, I've studied professionally. Other ones, I've written about a lot because I'm a science communicator. I've, I have a newsletter. I've written for a lot of magazines. And so for some things, it was pretty easy to sit down and write them. For other things, there were just things I didn't know, so I had to go and look them up. And for a lot of them, I had a basic grip on the physics or what it would be like, but actually knowing the numbers. So if I'm going to describe for example, well, how much does the temperature drop on a planet orbiting a binary star when one of the stars blocks the other one, and well, it turns out I did something similar to that in graduate school to get my PhD. I worked out some of the math for that, but doing it for this was different, and I had to back out of that equation that I remembered and actually derive it because it wasn't quite right for what I needed to do. So I had to, like, dust off my brain from 30 years ago being in graduate school and go, Oh, yeah, how do we do this physics? And eventually got the right numbers. And so the book doesn't have any math in it, but there's a lot of math that went into it, and I had to make up, oh my gosh, spreadsheets. And let me tell you something, I hate spreadsheets. That's how much I wanted to write this book. I hate doing spreadsheets. But to talk about, for example, TRAPPIST-1 is a star near Earth that has seven planets orbiting it, and they're all about the same size as Earth. And you can see them. Each planet, you can see the other six planets. But how big are they? How big do they get? And I had to write all of this math down and put it in a spreadsheet so that I had it in front of me, because it was complicated, I couldn't remember all these numbers. So yeah, there was a lot of reading, a lot of research. So like any science book, there is a lot of research that goes into it that you never see, but it does inform the prose. So it was a lot of fun to do all that.

O'NEILL: Well, you've got all this professional experience, and you've clearly got all this passion for learning. What are you still looking to learn?

PLAIT: Everything. That's an easy one. Any scientist will tell you that. I mean, they'll say, Well, you know, I'm studying the mitochondria of a squid that lives in the Mariana Trench. But in fact, the beauty of where I am in my life as someone who has a degree in astronomy, who did professional research, but is now a science communicator. There is nothing I won't write about if it has to do with astronomy. So if it comes to learning about what the dust on the moon is like, I want to know about that, and I want to write about that. If it comes to the ultimate fate of the universe, that's another thing I'm interested in. So everything in between, from Earth to the edge of the universe, that's stuff I want to know about. There's no end to this search for knowledge, and there's no limit to it. I want to learn everything, and I want to learn everything about everything.

O'NEILL: As things stand, we do not currently have the kind of galactic sightseeing trips that we imagine when we read Under Alien Skies.

PLAIT: Yeah, I know it's a rip off, isn't it? I wish I were born 100 years from now, yeah.

O'NEILL: But for those of us who do have an interest in astronomy, how might we do a little space exploration from Earth?

PLAIT: Yeah, the one thing about astronomy is that you don't have to spend 1000s of dollars or get a PhD or do all of that stuff. You can simply walk outside and look up. Now, it's not that easy, if you live in the middle of a big city, or you live, I don't know, in the Pacific Northwest, where it rains nine months out of the year, or something like that. But if you have clear skies and you can see the moon, you can watch the Moon change phases. You can get yourself a pair of eclipse glasses. You can buy those online for like two bucks, and you can look at the sun. And right now, the sun is very active. There are a lot of sun spots, and a lot of them get big enough to see by eye. Don't look at the sun without protection, but if you have these eclipse glasses, you can safely look at the sun. You can go out on dark nights. Watch for meteors, watch meteor showers, look at satellites as satellites are passing overhead. That's how I got my start. I went out and just looked up. And it's amazing what you can see without having to spend a lot of money. You need to spend the time to get familiar with the sky. If you have a phone, you can download planetarium apps. There are a zillion of them, and they can tell you where you're looking in the sky. So it's really just a matter of saying, I want to do this. I'm going to do this. Go outside and do it. And it's amazing what you can see.

O'NEILL: Philip Plait is the author of Under Alien Skies: A Sightseer's Guide to the Universe. Phil, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

PLAIT: Oh, it was my pleasure. I love talking about this, so thank you.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth