November 29, 2024

Air Date: November 29, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

UN Climate Summit Falters

View the page for this story

The UN climate treaty summit known as COP29 teetered on the edge of collapse as less developed nations implored the rich countries of the global north to provide financial relief to help them cope with rising climate costs. Alden Meyer, senior consultant with E3G, was at the COP and joins Host Steve Curwood to explain the frustrations with the process and the compromise delegates eventually reached. (16:42)

Seal Island

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

The rocky coast of Maine is an ecological hotspot but to see a lot of its wildlife, you’ll have to venture out to sea. And that’s where Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender found himself not long ago. (02:48)

Event Promo -- Susan Casey on the Deep Sea

View the page for this story

Living on Earth and the New England Aquarium will host a live author interview on December 5 online and in person in Boston. In a promo clip from a previous interview on the show, Susan Casey speaks about the mysteries of the deep ocean captured in her book The Underworld. (03:29)

Under Alien Skies: A Sightseer's Guide to the Universe

View the page for this story

Astronomer Philip Plait wondered what it would be like to walk on Mars, fall into a black hole, or fly through a nebula, so he wrote a book, Under Alien Skies: A Sightseer’s Guide to the Universe. He joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to reveal the strange colors of a sunset on Mars, what it’s like on a planet orbiting binary stars, the unique challenges of landing on an asteroid, and more. (21:20)

Star Sounds

/ Aynsley O’NeillView the page for this story

NASA turned infrared, optical, and x-ray data from space into sound in a process called “sonification,” so we can “hear” the gorgeous spiral galaxy known as the Phantom Galaxy. And within our own Milky Way galaxy is the Jellyfish Nebula, the remnant of an exploded star. Host Aynsley O’Neill walks us through these otherworldly sounds. (01:43)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

241129 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: Susan Casey, Alden Meyer, Phil Plait

REPORTERS: Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

The recent UN climate treaty summit almost collapses as it falls far short of what’s needed.

MEYER: This is not charity. It’s a matter of justice, and it’s a matter of our own environmental security and economic self-interest. But so far there’s been a lot of putting short-term self-interest ahead of the global public good, and what the citizens of the world expect and deserve and need.

CURWOOD: And if you like science fiction, science fact can be even more amazing.

PLAIT: We all remember Luke Skywalker standing at sunset on Tatooine, with his leg on the rock and the wind whistling through his hair as these two suns set on the horizon. That’s an iconic scene. But it’s also kind of correct! They kinda got that right!

CURWOOD: A sightseeing guide to the universe and more this week on Living on Earth—stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

UN Climate Summit Falters

Antonio Guterres, secretary-general of the United Nations, speaks at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan. (Photo: The Presidential Press and Information Office of Azerbaijan, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

O’NEILL: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Teetering on the edge of collapse, the 29th Conference of the Parties or COP of the UN climate treaty recently concluded in Baku, Azerbaijan. With more and more massive storms, floods, heat waves and wildfires, the less developed and poor countries demanded 1.3 trillion dollars a year by 2035 to help them address the growing troubles from global warming. The rich countries of the Global North first refused to put any numbers on the table during the round the clock talks. Finally, to break the impasse, negotiators set the goal of 300 billion dollars a year by 2035, with commitments to be clarified at the next COP in Brazil. That’s up from the 100 billion a year pledged back in 2009, though critics said with inflation, that would not be much of an increase if at all.

The COP also failed to affirm a commitment to “transition away from fossil fuels” that was adopted at last year’s session in the UAE. Alden Meyer is a senior consultant with the group E3G who has been to all but one of the annual COPs of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. He stepped off his 20-hour plane ride back to Washington from Azerbaijan to join us. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Alden!

MEYER: Great to be with you again, Steve.

CURWOOD: Alden, how high were the passions? I mean, what was there in terms of a walkout or a threatened walkout during these negotiations? I've heard some say that the UNFCCC had a near death experience. How accurate is that?

MEYER: Well, it came very close to a crisis or a collapse. There were two groups of countries, the Least Developed Countries, and the Alliance of Small Island States, that did a walk out of some negotiations that were happening. They complained that they were not being listened to, that other delegations were being briefed when they weren't. They didn't feel respected. The developing countries were very adamant that the need was much greater than the $300 billion that was pledged at the end. They also said that this really did not represent the responsibility or the capacity of the developed countries to put funding on the table. Another factor that came up here was anger amongst the developing countries that the Europeans, US, UK, and others from the developed countries did not put an actual figure on the table until at the end of the second week of the negotiations. It did come very close, I think, to being a crisis where they would have either had to suspend the meeting and resume in Bonn, or adjourn the meeting with no decision and resume negotiations a year from now in Belem, Brazil. Neither of those options were particularly palatable, partly because everyone is quite aware of the change in US administrations two months from now, and also aware of some of the dynamics in other countries where there are elections, in places like Canada and Australia, which could also result in a change of position on some of the key countries. So there was an incentive to get this deal done now, and I think at the end of the day, that was the calculus that most of the developing countries made.

After many tumultuous days of negotiating, COP29 in Azerbaijan ended with a goal that developed nations will provide $300 billion annually to less developed and poor nations to help them fight climate change. (Photo: The Presidential Press and Information Office of Azerbaijan, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

CURWOOD: Now, what about the process, though, Alden? I understood that India was trying to object at the very end, didn't feel that consensus had been reached, but the deal was just gaveled through anyway.

MEYER: That's correct. The Indians had serious concerns both about the overall number, the magnitude of the number being inadequate, and also because of some of the blurring of the lines in the agreement between developed and developing countries. It allows, for example, the developing countries' share of activities and financing by the World Bank and other multilateral development banks to be potentially counted towards that $300 billion. India didn't feel it was particularly equitable, and so they had let the President know that they planned to object to this, and he did go ahead and gavel it through before they were given the chance to take the floor. And they were quite angry about that. There were a couple of others that came in with similar concerns, Bolivia, and Nigeria as well, but the agreement was adopted. This, of course, has happened before over the nearly 30 years history of this process, but it certainly left a bitter taste in the mouth of India and some of the other developing countries.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about the things that the developing countries really don't like about this deal, aside from the overall money number, saying that it's not enough. How do they feel about the burden that they are going to bear under this agreement, and what was kind of decided in the back room, as opposed to out with full transparency?

MEYER: Well, other aspects of it they don't particularly like are that it allows a variety of funding sources to be counted, not just the bilateral funding from developed country treasuries, but also the multilateral development bank funding. It also allows leveraged private finance to count towards the goal, and of course, it doesn't promise that a much more significant share of finance will be coming in the form of grants or concessional low-interest rate loans. They were making the argument that giving us commercial loans and making us pile on more debt when many of us are facing insolvency and debt crises, is not acceptable. So that was one of their concerns. Another one was this blurring of the lines, as you said, between developed and developing countries. The way that was framed in the end was it was left entirely voluntary for developing countries to step up and say that they would provide finance towards this. And of course, it wasn't clear that that had to be on top of the $300 billion commitment. And therefore there was some concern that some of those voluntary funding commitments by developing countries could be used to actually water down further the commitment of developed countries, which most of the developing countries felt was already grossly inadequate. So those were two of the big concerns we heard, and then just the whole way the negotiations were conducted, the incompetence of the presidency, the fact that not all groups had been consulted, the fact that some countries had more access than others. In the second week, it came out that the Saudis had been allowed to edit a draft decision put out by the presidency on the just transition work program. That's kind of unprecedented. So there were a number of concerns that developing countries had, but I would say, when it comes to the behavior and sort of strategy of the presidency, that was something that united almost everyone, developed and developing countries, a lot of anger towards the end of the two weeks about how the process had gone.

Developing countries like Nigeria, which experiences increased drought, desertification, and precipitation changes due to climate change, claim the goal is woefully short of developing country financial needs to assist with this problem and reflects the lack of responsibility taken by developed nations. (Photo: Iwuala Lucy, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: So what does that say about the risk of having a petro-state, I think Azerbaijan gets what, most of its foreign exchange from fossil fuels, huge part of their local economy, their export economy? They have a vested interest in staying in the fossil fuel business.

MEYER: Well, that's true. That was also true for the United Arab Emirates, which hosted last year's COP, but in contrast with the Azerbaijanis, they were quite skillful in their management of the negotiations and diplomacy. They have been engaged in these negotiations in an intense way for much longer. They were up to speed on the issues. They have, I would say, a more sophisticated diplomatic corps and service. And of course, they were able to engineer the language calling for the transition away from fossil fuels in the energy sector, against the vigorous opposition of the Saudis, which was quite a feat, actually, because you've got to think about it, the Saudis had succeeded for 28 years in blocking any mention of the need to transition away from fossil fuels in a COP decision, even though everyone knows that fossil fuels are responsible for about 70% of the emissions driving the climate emergency. So both are petro-states, but one was seen as more sophisticated and skillful in the way it conducted the negotiations than the other.

CURWOOD: So Alden, this COP did not have language saying that we're phasing out fossil fuels.

MEYER: It did not, and of course, neither did last year's COP. That was the original proposal that many countries put on the table, phasing out or phasing down fossil fuels. They were not able to get that. What they did get was a statement of the need to transition away from fossil fuels in the energy sector, and even that, there's kind of a collective amnesia about that having happened at this point.

CURWOOD: Now, there was another outcome of COP29 that did work for the Global North and the folks who make a lot of money and move a lot of money, and that was an agreement on some of the rules for the carbon trading market. Can you walk us through what was decided there and why it benefits the rich part of the world?

The delegation from India objected to the final agreement, but it was gaveled through by the president anyway. (Photo: chmoss, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

MEYER: Well, this is a topic that got into the Paris Agreement. It's called Article Six of the Paris Agreement, and there's two major components of it. One is setting up a new sort of international body to allow trading of so called offsets or credits, where a country that has a hard time meeting the commitments it's made in our their own country might make investments in another country where reductions would be considerably cheaper, and they could count those reductions against their own commitments, even though they weren't happening in their own territories. And so this has been kind of a hanging issue for I guess six years now, they finally did reach agreement on the rules for these two kinds of trading mechanisms. The one, as I said, is sort of an international mechanism. The second is to regulate country to country trading. The concern that many environmental advocates have is that the rules may not fully make sure that you have environmental integrity in the system, that the tons that are being traded really represent additional activities that wouldn't have happened otherwise, that there's not full consultation with civil society, with indigenous peoples, about the impacts of some of these investments, particularly in developing countries.

[MUSIC: Vulfpeck, “Smile Meditation” on Thrill of the Arts, Vulf Records]

CURWOOD: We’ll be back in a moment with more from Alden Meyer on the latest UN climate summit. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Vulfpeck, “Smile Meditation” on Thrill of the Arts, Vulf Records]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green, and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Vulfpeck, “Smile Meditation” on Thrill of the Arts, Vulf Records]

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

We’re back now with Alden Meyer, a veteran of the UN climate summits who’s been filling us in on the carbon credit deal reached at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan.

CURWOOD: And why does carbon trading, why do these offsets benefit richer countries?

A loose set of rules for a carbon trading market was established at COP29. (Photo: UN Trade and Development, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

MEYER: Well, they benefit richer countries because, as I said, they can often be less expensive than making the investments in your own backyard. And so that's another concern that some developing countries have had about this. They say, basically, you're taking the benefits of the low hanging fruit in our countries when it comes to emission reductions and using it to avoid cracking down on polluters in your own country. So there's quite a bit of concern about the equity and fairness about this. The other thing is that now that we're committed to trying to achieve the Paris temperature limitation goals, which require us to get to net zero global emissions by mid-century, and actually net negative emissions in the second half of the century, the whole concept of offsets or credits may not make as much sense. If everyone has to get to zero, trading among yourselves so you do less and shift some of the burden to someone else, doesn't really work. The counter argument that those favoring it use is that you can get more bang for the buck in terms of investment of limited resources. So if you have a billion dollars to invest, and you would get twice the emission reductions by doing it in a developing country rather than your own country, these advocates say, you're actually getting more ambition for the same amount of money. So this has been a long debate. They finally did resolve it in Baku, and now we'll move into implementation and watch how it actually works.

CURWOOD: Alden, at the end of the day, how selfish is the Global North being here? Some would say that Global North is being penny wise but pound foolish. They are creating a disaster for the whole planet, and ultimately won't make the kind of money that they think they can make. What's going on?

Some are concerned that a carbon credit trading system will further stall meaningful emissions reductions. (Photo: barnyz, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MEYER: Well, I think there's a lot of truth to that. If you look at the financing of these responses, you can make a very strong case that it is in our self-interest to be more generous in supporting these activities, both in terms of mitigation and adaptation. On mitigation, the developing country is now responsible for a majority of emissions, and that will continue to grow as their economies grow and they lift more people out of poverty. It matters tremendously to our ability to limit temperature increases and devastating impacts from climate change if we help them pursue that development model in a different way than we did, if we help them leapfrog over fossil fuels to clean energy technology. And also, of course, that can create markets for exports of technologies and creation of jobs at home in some of these sectors to help developing countries do that. On the impact side, on adaptation, it's obviously in our self-interest to avoid the kind of impacts, the food and the water crises and other things that drive instability, drive mass migration, create failed states and havens for terrorism, you know. And for example, it's pretty well understood now that the drought in Syria was a contributing factor to the instability there in the Civil War, which led to mass migration into Europe, which then destabilized a number of governments and led to the success of right-wing populist candidates. So these are issues that I think there needs to be more awareness of in the Global North. This is not charity. It's a matter of justice, and it's a matter of our own environmental security and economic self interest.

Although his second term has yet to begin, delegates from across the globe discussed the possible implications of Donald Trump’s second presidency for global climate action. (Photo: Office of the President of the United States, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: And perhaps survival as well.

MEYER: Yeah, there's that, if you've got to be serious about it. We are currently experiencing devastating impacts of climate change at around 1.2 or 1.3 degrees Celsius, and right now, the latest predictions are that we're on route to either 2.5 to three degrees Celsius, and those would be truly terrifying impacts. And of course, what keeps a lot of scientists up at night is not knowing when we would cross thresholds, so called tipping points, that would lead to irreversible changes in the climate system and kind of accelerate those impacts. So there's a lot at play here, and certainly the world that we're leaving to our children and our grandchildren is something we ought to be thinking pretty deeply about.

CURWOOD: Alden, these meetings, these conferences of the party of the UNFCCC, it's a grueling process. What keeps you going? How do you keep having hope?

Heads of State, Ministers and other leaders at COP 29 in Baku. Next year COP30 will be held in Belem, a city at the mouth of the Amazon River in Brazil. Many developing nations are preparing for another intense battle of negotiations. (Photo: The Presidential Press and Information Office of Azerbaijan, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

MEYER: Well, I'm kind of a congenital optimist, I guess you would say. Others would call me a serial masochist for repeating the same thing and hoping for a different result. We do make incremental progress over the years, step by step. If we didn't have the Paris Agreement and the actions that countries have taken over the last decade, some of the predictions are we might be heading for four or five degrees Celsius. So, you can't say it's totally ineffective or doesn't matter. It does. The problem is, as we've discussed before, we're not moving at the pace and scale that the science requires. We are responding, but it's too incremental, it's too slow, and it's hard to get countries and leaders to focus on this when they're facing crises and conflicts in the Middle East or Ukraine, instability in their own countries because of inflation and poverty and inequality. This seems like something that's far off and far away, but of course, it's not, and it's happening now. It's being experienced all over the world, and it's compounding some of the political and economic crises that that leaders are facing. That is starting to sink in, and I'm hoping we can build on that and build more political will in Brazil and in future years to come, to come to grips with this crisis. But you would have to say, so far, there's been a lot of putting short term self-interests ahead of the global public good and what the citizens of the world expect and deserve and need.

CURWOOD: Alden Meyer is a Senior Associate at the climate think tank, E3G. Alden, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MEYER: Thanks, Steve. It was good to talk to you again.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “Overtime Deal at COP29 Falls Short of Global Climate Finance Needs”

- The Guardian | “Saudi Arabia Accused of Modifying Official COP29 Negotiating Text”

- The Guardian | “COP29’s New Carbon Market Rules Offer Hope After Scandal and Deadlock”

- Watch: Indian delegate slams COP29 finance deal

[MUSIC: Chingiz Sadykhov, “Ala Göz” on Piano Music Of Azerbaijan, 7/8 Music Productions]

Seal Island

Seal’s head pokes up above the water. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

O’NEILL: The rocky coast of Maine is an ecological hotspot but if you want to see a lot of its wildlife, you’ll have to venture out to sea. And that’s where Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender found himself not long ago.

Namesake

Horsehead Seal

Seal Island

Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge

© 2024 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

John Drury, one bare foot on the gunnel the other on the dock, fends off, takes the wheel, throttles up so smooth, I’m on the work deck checking the camera gear and it’s only when I glance astern and the ferry slip at Vinalhaven Harbor is no longer in sight, I realize, we are under way. And then the sea takes us and there’s no mistaking it. We rove and yaw in the headwind and the swell. Seal Island lays on the horizon, dead ahead.

These are the waters of the Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge and they are gushing with life. Beside us in the water young shearwater, their plumage brown and white and soft. Naïve to us they look at me without judgment, no opinion having been formed of human beings one way or the other. Rain threatens but there is none. A pair of harbor porpoise, a mother and her calf of the year, their backs and dorsal fins obsidian black in the half-light cut across our wake. They dive, leaving no trace.

An hour later we are there.

Great slabs of bedrock clamber for space cracked and cleaved where ice and time have split the stone; a vertical of gray basalt where molten magma crept from the belly of the earth; the smooth slope where Ice Age glaciers shaved the granite clean and a live beard of seaweed meets the waterline:

A bob of horsehead seals. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Seal Island.

John Drury pilots us to the backside where the surf rolls in from the Shelf and there they are, true to the island’s name, a bob of horsehead seals! Old bulls, females and their young. Unlike the shearwater, wary, though they know this is a place of safety. And they stay. Where they are. And raise their heads neck and shoulders above the water as if on solid ground, “Who’s this? What does he want? Why is he here?”

They look at me and have their doubts. I look at them and my thinking is the same.

How fragile it is. This luxury to question.

O’NEILL: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Maine coastal wildlife guide, Captain John Drury can be reached through his website

- Mark Seth Lender’s wildlife photography can be found here

- More about Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge

[MUSIC: Noah Kahan, “Maine” on Cape Elizabeth, Republic Records]

Event Promo -- Susan Casey on the Deep Sea

The Underworld: Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean, from bestselling author Susan Casey. (Photo: Courtesy of Penguin Random House)

CURWOOD: Join us on Thursday, December 5th online or in person at the New England Aquarium in Boston for our next live author event, “Exploring the Deep Sea with Susan Casey.” Susan will discuss her book The Underworld and reveal some of the mysteries of the deep ocean, home to otherworldly marine life, soaring mountains, and smoldering volcanoes. Mysteries like the “twilight zone.”

CASEY: When people think of the ocean, they typically think of the very uppermost layer, which is the sunlight or photic zone, where there's light through the water. And even at the deepest you can scuba dive, you're still seeing sunlight, at least there is sunlight in the water. But below that is the uppermost layer of the deep ocean, and that's the twilight zone or the mesopelagic zone. And that goes from 200 meters, so about 600 feet, down to 1000 meters, so about 3300 feet. And then below that you have another vast midwater area called the midnight zone that goes from 1000 meters to 3000 meters. Below that you have the abyssal zone, or the abyss, which goes - it's the largest ecosystem on Earth, and it's 3000 meters to 6000 meters. And then below that, in certain parts of the ocean, there's the deepest part. It's where the tectonic plates collide and one plate is being subducted beneath another, and that's from 6000 meters almost down to 11,000 meters in the deepest spot in the ocean. That's called the hadal zone. And those deep areas are called hadal trenches, where these tectonic plates are colliding. The Mariana Trench is one that people tend to know. But there are dozens of others. And so the deepest spot that we know of is called the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, and that's 35,867 feet by our latest calculations. It's actually very hard to get an exact depth calculation. And I went as far down as the abyssal zone. I went about 17,000 feet, about 5200 meters. I also went through the twilight zone, which is really amazing, because (@5:37 in original 2-way) I call it the Manhattan of the deep, because there are more creatures living in the twilight zone than in all the other regions of the ocean combined. So it's a really active place and very scenic because all these creatures are illuminating themselves and flashing and blinking and wafting in front of you and sparkling. The abyss is... it took us two and a half hours of free falling to get down into that realm and get the sense that the deeper you go, the more profound it feels. You're definitely aware of the weight, the pressure. I mean, that's 500 atmospheres on your head. There's a gravitas to it. But there's also a serenity, a real serenity. You realize that it is not space, because it's alive. I never forgot where I was. But I was in such awe of where I was that the time goes very elastic, like you could be down there for an hour and you would think you were down there for 15 minutes. There's no signposts. There's none of the things that we tend to look for above, you know, that give us a sense of our surroundings. It's all fluid. It's a spectacular experience that really changes your perspective of your place on Earth. This vast, vast, vast region that we never even think of - it is the vast majority of the Earth. So it's amazing to meet it.

CURWOOD: Join Susan Casey and me on Exploring the Deep Sea, Thursday, December 5th at 6:30 p.m. Eastern, online or at the New England Aquarium. Find out more and sign up for this free event at the Living on Earth website, loe.org/events.

Related links:

- Learn more about this upcoming live event

- Direct registration link from the New England Aquarium

- Purchase a copy of The Underworld (Affiliate link supports Living on Earth and local bookstores)

[MUSIC: Thomas Newman, “Wow” on Finding Nemo (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack), Walt Disney Records . Pixar Animation Studios]

Under Alien Skies: A Sightseer's Guide to the Universe

Philip Plait’s 2023 book, Under Alien Skies: A Sightseer’s Guide to the Universe, explains what it would be like to explore outer space. (Photo: W. W. Norton)

O’NEILL: From Star Trek to Star Wars to Treasure Planet, fictional portrayals of outer space are everywhere. But if you’re wondering what walking on Mars, flying through a nebula, or falling into a black hole would actually be like… that’s better left to science fact than science fiction. Luckily, one astronomer has written a book all about these strange realities. Under Alien Skies: A Sightseer’s Guide to the Universe takes readers on a cosmic journey while teaching them what the universe outside our little blue planet is really like. Joining us now is author Philip Plait, former member of NASA’s Hubble Telescope team, and writer of the newsletter called Bad Astronomy. Phil, welcome to Living on Earth!

PLAIT: Thank you. It's nice to... well, it's nice to live on Earth. So thanks.

O'NEILL: So Phil, Under Alien Skies has these really engaging descriptions that sort of imagine what it would be like to travel to various places in outer space. Could you please read from the first two paragraphs or so from the chapter on Mars?

PLAIT: Yeah, sure. I'd be happy to. “You're out of bed early, suited up and out the airlock before anyone else is awake. It's not strictly protocol. The commander says you should have a buddy with you when out on the surface when possible. But you love seeing the landscape as the sun rises. You walk out a ways from the hab module until the view to the east is clear. Facing west first, though, you watch as the black sky above you turns butterscotch in a slow wave moving down toward the horizon. As you turn to face east, the sun appears, and the sky around it turns a shade of pale blue. Even so, there are still stars visible. The thin air doesn't scatter enough light to entirely block them, even when the sun is up. One stands out though, a blue green jewel shining a few degrees above the sun. That's home you think, Earth some 50 million miles sunward.”

O'NEILL: And now these sections walk the line between non-fiction and sci-fi. What made you decide to incorporate little fictional scenes into this science book?

PLAIT: Oh, that's easy. I'm a dork.

O'NEILL: You're in good company.

PLAIT: Yeah, there are millions of us. For me, science and science fiction are both ways that we describe reality. And in science fiction, we use our imagination, right? We have science that we don't necessarily have yet, whereas in actual science, we're using our imagination to try to imagine what these things are like that we're describing. You know, in astronomy, you've got some planet that we've discovered, and it's orbiting some star, and we know enough about the star and where the planet is to start guessing intelligently about what conditions would be like there. And by using our imagination, we can fill in some of those gaps. And the beauty of that in science is it gives you an idea of what you might want to look into next. Like, I wonder if liquid water could exist on this planet. Well, you know, it depends on the atmosphere. Well, what kind of atmosphere would it have? And so it's all of this imagination going into it. So for me to write a book about these places, starting each one off with a little science fiction vignette, an anecdote, that is me holding your hand and showing you all of these amazing places that astronomers, we live our lives in. We just can't actually go there typically.

Phil Plait is also the author of Death from the Skies and Bad Astronomy. (Photo: Marcella Setter)

O'NEILL: Well, one aspect that I really enjoy is that you incorporate, of course, the science fiction, the science fact, but you also go into the history of astronomy. You talk about how we found out what we know now. Tell us a little bit more about the history of astronomy that you put into this book.

PLAIT: That was another easy decision because something that really bugs me about the way people think of science is they think of it as like a compendium of facts. It is a dictionary that you open up to what our star is made of, and you look it up and it's, oh, hydrogen, helium, blah, blah, blah. And how do you know that? You read it in a book, but how do you know the book's right? So by throwing in the history of how we learn some of this stuff, it makes it more like what science really is, and that is a process. Science is not something you look up. It is something that learns and grows, and it's almost like its own organism. It's almost like a living thing. Science doesn't just grow linearly. It's not just we learn this, then we learn this, and then we learn that. It's not like that. And so it's kind of fun to put stuff in the book that says, you know, hey, this was a matter of some debate, and then it turns out this person was right, or they were both wrong, or something like that. It makes it more human. I talk about how the first planets around other stars were discovered. It's one of my favorite stories in all of science. Basically, some scientists had announced that they had found a planet orbiting another star, and then turns out they were wrong. They had made a mistake in the way they observed their data. And they had to stand up in front of a group of their peers and say, We messed up. And then the next team of scientists walks up to the microphone and said, Yeah, we actually have discovered a planet. We didn't do the same thing they did, and our data are good. And yeah, they were right.

O'NEILL: Wow.

PLAIT: Literally, the next people to talk at that conference. You know, you couldn't write that in a TV show, but it really happened. And so I just, I love it. I just love stuff like that.

O'NEILL: And one of the amazing facts that we learned via that scientific process is that Mars has a sort of color flipped version of Earth's sky. So during the day, the Martian sky is a sort of orangey red, but then it turns blue at sunrise and sunset. Why is that the way it is?

PLAIT: Right, it's the opposite of Earth. During the day, our sky is blue, and then when the sun sets, the sun kind of turns red, and the sky around it turns red. And for us here, it just has to do with the way Earth's atmosphere scatters blue light. So red light can just pass right through our atmosphere, but the blue light from the Sun bounces off these molecules in our atmosphere, and then can come at you at any random direction. So anywhere you look in the sky, you see blue, but you only see red when you're looking toward the sun. On Mars, it's the opposite. Mars has all of this dust in the atmosphere that is heavily laden with rust. It's iron oxide, different kinds of iron oxide, but it's rust. And so you know, you know what the color of rust looks like. It's that orangey hue. And so during the day, the sunlight passing through Mars's atmosphere is lighting this dust up. And so it looks orange. However, near the Sun, there is another effect that takes place, and it has to do with the way light is scattered. But that blue light is scattered toward you. And so when you are looking near the sun, the sky looks blue. I mean, even during the day, even at noon, but at sunset, that effect is magnified a lot. And so the sunsets and the sunrises on Mars are going to look blue near the sun. So it's the exact opposite of Earth, even though it has an atmosphere, and it's kind of Earth-like and all this stuff, you wind up getting the exact opposite thing that you might expect. It reminds you that Mars is an alien world.

[MUSIC: Harry Gregson-Williams, “Making Water” on The Martian: Original Motion Picture Score, Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation]

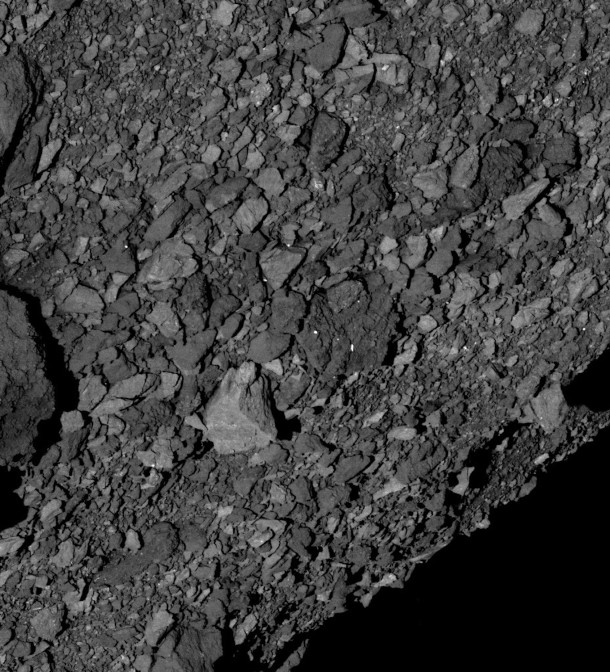

The chapter on asteroids was Plait’s favorite to write. Asteroids may look solid, but they are really just rubble piles held together by gravity. (Photo: NASA, public domain)

O’NEILL: In a moment, we’ll travel to other alien worlds with astronomer Philip Plait, who’s speaking with us about his book Under Alien Skies. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Harry Gregson-Williams, “Making Water” on The Martian: Original Motion Picture Score, Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Harry Gregson-Williams, “Sprouting Potatoes” on The Martian: Original Motion Picture Score, Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. We’re back with Phil Plait, astronomer and author of Under Alien Skies.

O'NEILL: This book doesn't just cover places within our solar system. It also goes into detail about what it would be like to be outside of our little cosmic neighborhood, and it includes a section about a planet that orbits two suns. Tell me more about that chapter and about the idea of this binary star system.

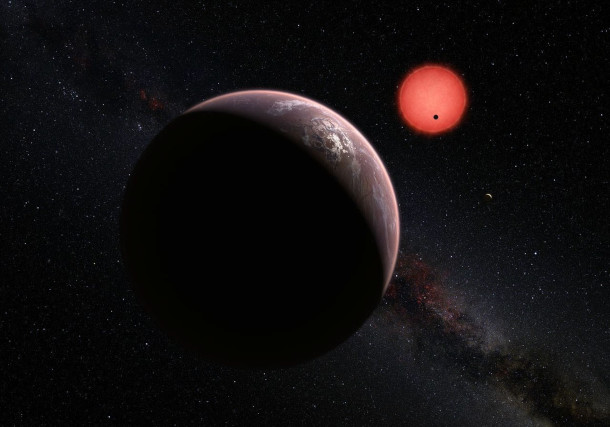

PLAIT: Right, how could I not write about this? It's so cool. I mean, we all remember Luke Skywalker standing at sunset on Tatooine with his leg on the rock and the wind whistling through his hair as these two suns set on the horizon. That's an iconic scene, but it's also kind of correct. They kind of got that right. Tatooine orbits two stars that are both kind of like the sun, and it's on a, it's what's called a circum binary orbit, which means it goes around both stars. You can also have binary stars, two stars that orbit each other and have a planet only orbiting one of them, and the way the sky looks in these circumstances are different, especially if you orbit one star and the other one is orbiting much farther out. There are times of the year when it's always bright out. You've always got a star up in the sky. The star you're orbiting sets, but this other star farther out is still up in the sky, and it would be very bright, like brighter than the full moon, so you'd still be able to go out and do things at night. Other times of the year, when they're lined up and both in the sky near each other, they would set and it's dark, just like it is on Earth. So you'd have these really weird seasons where night time changes quite a bit. And if you orbit both, it's also very strange, because you have two stars in the sky, they'll cast two shadows, kind of, sort of. I exaggerated that a little bit for the book, that you would see two shadows. It's not that obvious. However, if these stars orbit each other very closely together, as they would have to, if you orbit both, sometimes one will pass in front of the other one. You'll have essentially an eclipse, except you're not blocking a star with the moon. You're blocking a star with another star. So instead of two stars in your sky, now you have one, and the temperatures will cool off very rapidly. And so I had a lot of fun extrapolating what life would be like. What would it be like to live on a planet where sometimes it doesn't get dark at night and other times it gets very cold suddenly for an hour or so during the day, even in the middle of summer? It was very strange to think about this stuff, but a lot of fun.

TRAPPIST-1 is a planet that orbits a star other than our own sun. (Photo: NASA, public domain)

O'NEILL: Now, when the book is describing places outside our solar system, it does talk about how we may never travel to these distant locations, because it is, as far as we know, probably impossible to travel faster than the speed of light. What does this mean for the future of space exploration? And also, what does it mean for the possibility of finding extraterrestrial life out there?

PLAIT: Well, that's a big question. I was very careful in the book to use as much current science as I could, and when I can't, I'm very clear about that. So when we leave the solar system in the second half of the book, I make it clear. It's like, look, we don't have faster than light ships, but let's pretend we do, and we can just hop on board and travel to a globular cluster, a cluster with a million stars in it, and be on a planet that's orbiting one of these stars. But if we can't do that, what does that mean? Well, the search for life on other worlds isn't limited to us boarding the USS Enterprise and heading off into the deep black. We're looking in a lot of ways. We're listening for radio signals from intelligent life. We're looking for what astronomers called bio signatures, which are signs of, say, oxygen or water in the atmospheres of planets orbiting other stars. You don't have to go to these places to maybe find life. There are maybe, maybe, maybe ways of detecting it, even from Earth. And we don't know, because we haven't done that yet. We have a lot of really good ideas. I mean, that was just a couple. There are dozens of ways that astronomers are looking for life on other planets, but it would have to be passive. In other words, it would have to come to us, these signals, whether it's intelligence signals or the signal of oxygen in the atmosphere, for example. That's just how it is. Unless somebody figures out how to make a warp drive, we're not going there anytime soon. It would take 100 years to get to the nearest star, more or less. We understand that there is technology that could travel at a decent fraction of the speed of light. But even then, it's 40, 50, years just to get to the nearest star. That's a lifetime. You better be absolutely sure you know what you're doing when you close that hatch and head off. And right now, we're just not there yet.

O'NEILL: And so, Phil, you got to write about some really incredible places. Which chapter was your favorite to write?

PLAIT: Oh, you can't ask an author that. It's like asking a parent who their favorite kid is.

O’NEILL: I know.

PLAIT: But in fact, typically what I would say is Saturn. I love Saturn. Everybody loves Saturn. If you've ever seen Saturn through a telescope, it is just phenomenal. You can see those rings. You can see moons orbiting it. And a lot of astronomers, myself included, will tell you, I got hooked when I was a kid because I saw Saturn through a telescope. And I show people Saturn through a telescope, and it's just so much fun to watch their faces. This wave of awe comes over them. They gasp, they laugh, they shout. They can't believe that it's real. And so writing about Saturn was amazing. And so that's the easy answer, and that's what I usually say. But I gotta say, writing about asteroids was a lot of fun. I'm fascinated by asteroids, these chunks of rock and metal that orbit the sun, most of them out between Mars and Jupiter, so pretty far from the earth. Most people think of asteroids as these giant rocks that can hit the earth, wipe out the dinosaurs, maybe give us a pretty bad day. But as scientific objects, these are the precursors of the planets. These were the building blocks that built up the planets, including Earth. And we didn't know that much about them when I was a kid, and I would watch TV shows, and there'd be a swarm of asteroids that would, you know, wipe out the ship or make them go off course, or whatever. And it turns out, it's not like that. There are millions of them out there, but they're spread way out. And they're not just like giant chunks of rock, like you'd expect, like a mountain. The smaller ones are actually like bundles of debris. They're like bags of rocks. We call them rubble piles. And it's like go to a construction site and see where they've dug up all the rocks out of the ground. It's kind of like that. They're just rocks held together by their own gravity. And it turns out it makes them pretty different. The rocks are so fragile on these things that if you picked one up, you could easily crush it with your hand. And so if you try to land on an asteroid, you could literally fall right through the surface and find yourself buried inside this thing. Be like jumping into a box filled with styrofoam peanuts. They just scatter everywhere, and you fall right in. That was so surprising to me, but we had a space probe that did that. It touched an asteroid, and if they hadn't backed it out of there, it would have sunk right in. And I think that surprised everybody.

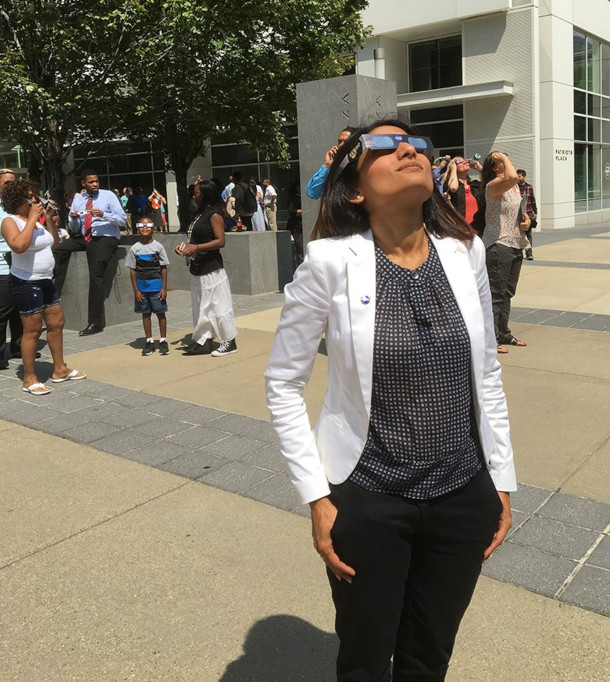

Plait recommends looking at the sun to see sunspots, but only wearing appropriate eye protection like eclipse glasses. (Photo: Mamta Patel Nagaraja, NASA, public domain)

O'NEILL: So reading this book, in some ways, provides a sort of escape from the problems here on Earth. I mean, especially with that second person perspective, you really feel like you're out there on Pluto. But some might say that given issues like climate crisis and conflict around the world that we shouldn't prioritize space exploration and space science. How do you respond when people say things like that?

PLAIT: Well, I understand that attitude, but it's not looking at it the right way. It's an ill posed question, as we like to say. First of all, it's not a dichotomy. It's not like we're spending all this money on space. We should be spending it on Earth. In fact, NASA's budget is so small, it's less than half a percent of the federal budget. As an astronomer once said, if you were to take the budget of the United States as a $1 bill, and you cut the edge off where NASA's budget is. You wouldn't even hit the ink. It's very, very, very tiny amounts. So the amount we're spending on the military is vast compared to space exploration. So I'm not saying we don't need a military, but we spend the money on a lot of things, and spending it on space exploration... really, there are much larger things you could turn to to say, why are we spending money on this? But also we're spending that money not in space. It's not like we're launching rockets full of $20 bills and letting them go. We're spending that money here on Earth, and we are learning about Earth. We have problems here. But how do you think we study climate change? If you're worried about climate change, you should be wanting to spend more money on space exploration, because we look at Mars, we look at Jupiter, we look at Venus, we study what the weather is going on there, and that informs us on how the weather works on Earth. It's a very, very complex set of systems, and by studying how it works on these other planets, it informs us on how it works here.

PLAIT: So Phil, you're obviously an expert on space, but I'm guessing you didn't know every single fact in this book before you wrote it. So what was the research process like?

PLAIT: Yeah, I do have a passing familiarity with a lot of the topics in this book. Some of them, I've studied professionally. Other ones, I've written about a lot because I'm a science communicator. I've, I have a newsletter. I've written for a lot of magazines. And so for some things, it was pretty easy to sit down and write them. For other things, there were just things I didn't know, so I had to go and look them up. And for a lot of them, I had a basic grip on the physics or what it would be like, but actually knowing the numbers. So if I'm going to describe for example, well, how much does the temperature drop on a planet orbiting a binary star when one of the stars blocks the other one, and well, it turns out I did something similar to that in graduate school to get my PhD. I worked out some of the math for that, but doing it for this was different, and I had to back out of that equation that I remembered and actually derive it because it wasn't quite right for what I needed to do. So I had to, like, dust off my brain from 30 years ago being in graduate school and go, Oh, yeah, how do we do this physics? And eventually got the right numbers. And so the book doesn't have any math in it, but there's a lot of math that went into it, and I had to make up, oh my gosh, spreadsheets. And let me tell you something, I hate spreadsheets. That's how much I wanted to write this book. I hate doing spreadsheets. But to talk about, for example, TRAPPIST-1 is a star near Earth that has seven planets orbiting it, and they're all about the same size as Earth. And you can see them. Each planet, you can see the other six planets. But how big are they? How big do they get? And I had to write all of this math down and put it in a spreadsheet so that I had it in front of me, because it was complicated, I couldn't remember all these numbers. So yeah, there was a lot of reading, a lot of research. So like any science book, there is a lot of research that goes into it that you never see, but it does inform the prose. So it was a lot of fun to do all that.

O'NEILL: Well, you've got all this professional experience, and you've clearly got all this passion for learning. What are you still looking to learn?

PLAIT: Everything. That's an easy one. Any scientist will tell you that. I mean, they'll say, Well, you know, I'm studying the mitochondria of a squid that lives in the Mariana Trench. But in fact, the beauty of where I am in my life as someone who has a degree in astronomy, who did professional research, but is now a science communicator. There is nothing I won't write about if it has to do with astronomy. So if it comes to learning about what the dust on the moon is like, I want to know about that, and I want to write about that. If it comes to the ultimate fate of the universe, that's another thing I'm interested in. So everything in between, from Earth to the edge of the universe, that's stuff I want to know about. There's no end to this search for knowledge, and there's no limit to it. I want to learn everything, and I want to learn everything about everything.

O'NEILL: As things stand, we do not currently have the kind of galactic sightseeing trips that we imagine when we read Under Alien Skies.

PLAIT: Yeah, I know it's a rip off, isn't it? I wish I were born 100 years from now, yeah.

O'NEILL: But for those of us who do have an interest in astronomy, how might we do a little space exploration from Earth?

PLAIT: Yeah, the one thing about astronomy is that you don't have to spend 1000s of dollars or get a PhD or do all of that stuff. You can simply walk outside and look up. Now, it's not that easy, if you live in the middle of a big city, or you live, I don't know, in the Pacific Northwest, where it rains nine months out of the year, or something like that. But if you have clear skies and you can see the moon, you can watch the Moon change phases. You can get yourself a pair of eclipse glasses. You can buy those online for like two bucks, and you can look at the sun. And right now, the sun is very active. There are a lot of sun spots, and a lot of them get big enough to see by eye. Don't look at the sun without protection, but if you have these eclipse glasses, you can safely look at the sun. You can go out on dark nights. Watch for meteors, watch meteor showers, look at satellites as satellites are passing overhead. That's how I got my start. I went out and just looked up. And it's amazing what you can see without having to spend a lot of money. You need to spend the time to get familiar with the sky. If you have a phone, you can download planetarium apps. There are a zillion of them, and they can tell you where you're looking in the sky. So it's really just a matter of saying, I want to do this. I'm going to do this. Go outside and do it. And it's amazing what you can see.

O'NEILL: Philip Plait is the author of Under Alien Skies: A Sightseer's Guide to the Universe. Phil, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

PLAIT: Oh, it was my pleasure. I love talking about this, so thank you.

Related links:

- Support Living on Earth and local bookstores by purchasing Under Alien Skies: A Sightseer’s Guide to the Universe

- Subscribe to Phil Plait’s Bad Astronomy newsletter.

- Watch Phil Plait’s Crash Course Astronomy series.

[MUSIC: SZA “Saturn – Instrumental” on Saturn, Single, Top Dawg Entertainment]

Star Sounds

Composite images and data from a series of infrared, optical, and X-ray instruments make up this view of Messier 74, a spiral galaxy also known as the “Phantom Galaxy”. (Photo: NASA, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

[SFX – Phantom Galaxy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2dgle5maku8&t=8s]

O’NEILL: We leave you this week with sounds from deep space.

[SFX – Phantom Galaxy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2dgle5maku8&t=8s]

O’NEILL: That’s the “Phantom Galaxy”, M74, which is a gorgeous spiral galaxy, just like our own Milky Way, that’s 32 million light-years away from Earth. What you’re hearing is infrared and optical data from the James Webb and Hubble Space Telescopes, plus x-rays from the Chandra observatory. NASA turned these signals into sound in a process called “sonification”, which creates an experience you don’t need to be a scientist to enjoy. So, what sounds like just the plucking of a harp actually represents stars and clusters.

[SFX – Jellyfish Nebula: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NqBfQeJqkfU ]

O’NEILL: Much closer to home at just 5000 light-years away is the Jellyfish Nebula, the remnant of an exploded star, or supernova. The Jellyfish Nebula appears right next to the foot of Castor in the Gemini constellation, but you’ll need a powerful telescope to see it. This sonification also draws on x-ray data from Chandra, as well as radio data from the Very Large Array. The water-drop sounds represent background stars.

[SFX – Jellyfish Nebula: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NqBfQeJqkfU ]

O’NEILL: You can find out more and see stunning images of the Phantom Galaxy and Jellyfish Nebula on the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

[SFX – Jellyfish Nebula: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NqBfQeJqkfU ]

[MUSIC: Count Basie, “Fly Me to the Moon – In Other Words” on This Time Basie, Reprise Records]

Related links:

- More NASA Sonifications

- Sonification of Phantom Galaxy

- Sonification of Jellyfish Nebula

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Josh Croom, Jenni Doering, Daniela Faria, “Mehek” Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, and El Wilson.

O’NEILL: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to Brian Benedict, refuge manager, Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth.

We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. And we always welcome your feedback at comments@loe.org.

I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth