Tornadoes in a Hotter World

Air Date: Week of April 4, 2025

A tornado looms near Harlan, Iowa. (Photo: Adam Orgler, World Meteorological Organization, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Experts are still trying to piece together how tornado patterns have changed in the last century and are likely to keep changing as the world gets hotter. Meteorologist Ryan Truchelut of WeatherTiger joins Host Steve Curwood to explain the eastward shift of tornadoes in the US and how newly vulnerable populations can stay safe.

Transcript

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

[Civilian camera footage]

[STORM SFX]

Cameraman: Oh, whoa! Tornado! Tornado, right here!

[ABC News footage]

“In the Midwest and the South, at least thirty twisters reported across six states…”

[NBC News footage]

“A dangerous and deadly outbreak of tornados ripped through eleven states…”

[NBC News footage]

"After a violent weekend of wind, rain, and tornados in the Midwest, more severe weather tonight…”

CURWOOD: March of 2025 saw over 200 confirmed tornados throughout the United States, including the largest outbreak on record for the month with a cluster of 116 verified tornados affecting the Midwest starting on March 13th. With all the destruction they can cause, tornados can seem massive, but on a global scale, they’re actually rather small and isolated. Of course, that’s no comfort to those who are affected, but on top of that, it also makes things difficult for the scientists who study them. Experts are still trying to piece together how tornado patterns have changed in the last century, and how they’re likely to keep changing in a warming world. The US has the most recorded tornadoes on the planet, and for why and how we go now to Tallahassee, Florida to meteorologist Ryan Truchelut of WeatherTiger.

TRUCHELUT: Well, the United States really is head and shoulders above other parts of the world in terms of frequency and severity of tornadic activity and severe weather. Of course, you can have tornadoes in other parts of the world, eastern China, South America, all these areas do get tornadic activity and severe weather, but the geography of the United States is particularly favorable for severe weather activity. Basically, that's because of the Gulf of Mexico is a ready source of heat and moisture that flows north into the continental United States, and then there's a large land mass going north into Canada, where you can have very cold air masses develop and then head south. So it's that contrast between the cold, dry air coming in from the north and that warm, moist air coming north from the Gulf of Mexico that's responsible for triggering these severe weather events that are quite frequent in the continental United States relative to the rest of the world. And in fact, the Rocky Mountains kind of being in the west central United States, they act as kind of a natural kind of focusing mechanism for that moisture moving north. And they also act, kind of, from a more technical perspective, as a triggering mechanism for the development of areas of low pressure over the plains that then tend to move northeast and drag fronts behind them. And that kind of all acts as atmospheric precursors to severe weather activity.

When dry air from the Rocky Mountains combines with moist air from the Gulf of Mexico, severe weather can brew. (Photo: G. Lamar, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So Ryan, as I understand it, the link between climate disruption and tornadic activity is not as well understood as, say that, between climate disruption and hurricanes and forest fires. But what do we know on that front?

TRUCHELUT: Sure, well, you know, it's a complex question, and it's something where, you know, we're trying to link changes on a global scale, big patterns of heat and moisture moving around the globe, to something that happens on a very small scale, a tornado or a severe thunderstorm that happens on the scale of a mile or 10 miles. So whenever you're going from that very large scale to the very small scale, it's complicated to do that, and sometimes you get things showing up in the data that, you know, you wouldn't necessarily expect or is a little bit surprising. So we're not really sure that there is a trend in terms of how much tornadic activity or how much severe weather is occurring in the United States generally. We're not sure over the long term with climate change, if that'll trend up or down, but what we do see in the data is there does appear to be a shift in the region where we're seeing severe weather and tornadic activity most frequently. So we kind of have this cultural concept of Tornado Alley across the plains. You know, there's nothing more American when people think about a tornado than a tornado rolling through a wheat field in Kansas or something like that. And of course, we're still seeing plenty of severe weather in the plains, but what we've really seen in the past twenty, twenty-five years is a shift of the most favored area of severe weather, kind of shifting out of the southern plains and shifting east into the Mississippi Delta region, into the deep South, into the Mid-South. So areas like Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, Alabama, Mississippi, these are regions where we really have seen a pretty strong trend towards not only more frequent severe weather and frequent tornadic activity, but also increasing the severity of the tornado activity that does occur there. So I mean, some of the tornadoes that have been the most destructive and the most damaging in recent years, you know, thinking about the Mayfield tornado, kind of cut across that Midwestern region, or kind of southern portions of the Midwest.

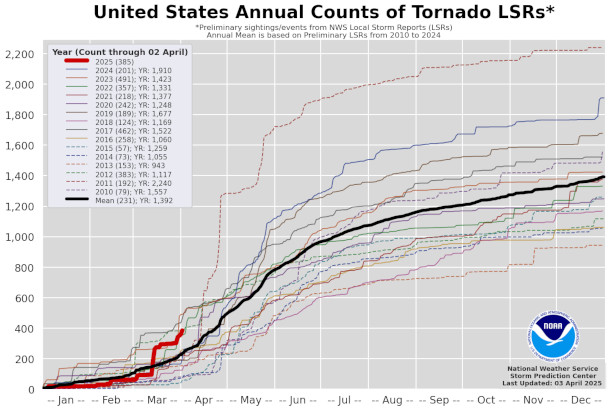

A graph demonstrating the count of U.S. tornado reports from 2025 (as shown in red) compared to the last 15 years. (Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So Ryan, when it comes to understanding climate disruption, scientists like to make these models, and they'll look at observations going back decades, even hundreds of years, if they can, and then roll that forward to see what might be happening to the climate. To what extent do we have the data to make such predictions with tornadoes?

TRUCHELUT: I would say that it is the toughest to do so for tornadoes of any of the damaging kind of weather phenomena that we look at. And the reason for that is simply that tornadoes, again, they kind of happen in these small scale, localized areas. And we don't have a great kind of even climatological record of how many tornadoes occurred. Because, you know, if you go back to the 1920s or the 1930s or the 1940s, we have records of tornadoes, certainly, but if a tornado didn't happen near a populated area, or if it was a short lived tornado, we may not have observed it. We may not know that it was there. So the records are quite fragmentary, especially before the 1980s. In the 1980s and 1990s we had the proliferation of more advanced Doppler radar across the continental United States, and that's allowed us to observe a much higher proportion of the tornadoes that occur. So we can trust the last 40 years of tornado data as being relatively free of what we would call observational bias. But really going back before that, we have records of destructive and damaging tornadoes, but we don't really have a good sense of if that number has changed from going 80 years back before the 1950s certainly. So it's tough, whenever you're trying to establish a trend, having a nice, clean, trustworthy data set is paramount. And unfortunately, with tornadoes, just because they're such a small-scale phenomenon, that's, you know, something that's challenging in the field.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about the science that shows that America's tornado hot spot is shifting eastward. What do you make of that?

TRUCHELUT: Well, we're seeing changes that are very notable in the timing of when is the last frost of winter occurring. So you know, if you go back and you look at agricultural records about when we've been planting crops across the southern United States or across the Ohio Valley, we're moving those planting dates forward very significantly, by several weeks over the past 75-100 years. So you know, the people who work with the land, people who work with the environment, you know, they're well aware of these changes that are occurring, because it's impacting their jobs. It's impacting, you know, agricultural practices across the country. So tornado threats and severe weather threats are linked to a contrast in temperature. That shift east, I think it's linked to what times of year that greatest contrast and where that greatest contrast is occurring. So the fact that springs are starting earlier, allergy season is starting earlier, we're planting earlier across the southeastern United States. So the fact that we're shifting that region east, I think, is just a follow-on effect of a changing of the timing of when we're transitioning from winter into spring. And of course, we really have seen that in 2025. There's been several large-scale tornado and severe weather outbreaks already in the month of March. You know, historically, sure, that's something that does happen, but the frequency of it does seem to be increasing over the Deep South and Mid-south.

CURWOOD: Is it fair to say that there were some lollapaloozas of tornado clusters in this spring here?

This home in Rolling Fork, Mississippi was flattened by an EF4 tornado at an estimated windspeed of 190mph on March 23, 2025. (Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

TRUCHELUT: Yeah, I mean, we've seen some outbreaks that produced a lot of very destructive tornadoes. There have been other outbreaks in the past that have produced more tornadoes, but the tornado outbreaks that we saw in March of 2025 really overperformed, unfortunately, from the perspective of EF2s, EF3s, EF4s. And those are the tornadoes that are, winds are 140 or 160, 180 miles per hour. And the force of wind, when you double the wind speed, you don't double the force that wind applies to a building. You quadruple it. So going from the 120 miles an hour wind gusts in a tornado to 180, you're really increasing the damage potential to people's lives and buildings and structures that are unfortunately in the path. So you know that over-performance of severe tornadoes and violent tornadoes unfortunately made some of the outbreaks of the last few weeks quite impactful.

CURWOOD: So Ryan, what kind of predictions do you care to make for this year's tornado season?

TRUCHELUT: Well, I think that we're going to have a pretty active pattern for severe weather continuing for the next six weeks or so. We've had some severe weather threats on the map for early April. We're probably going to go a little bit cooler and drier, maybe for mid-April, but I do think that we'll have additional chances of severe weather in late April and then going forward into early May across the eastern and central US, right in the heart of the new American tornado belt.

CURWOOD: So when it comes to climate disruption, some of the known effects, like hurricanes and storm surge and the fires associated with the drying out, these are things that people can think about and plan for, you know? Don't be so close to the coast. Don't have your house so close to where trees might catch on fire. What advice do you have for people who are concerned about tornadoes? What might they do about their living accommodations?

Ryan Truchelut is co-founder, president, and chief meteorologist at WeatherTiger. (Photo: Courtesy of Ryan Truchelut)

TRUCHELUT: Well, it's a tough question, because tornadoes can happen anywhere. I mean, they can happen along the coast. They can happen inland. You know, we're really looking at questions of: you had a preexisting risk, there was always a tornado threat across Arkansas or Alabama or Kentucky or Tennessee. The fact that these risks may be becoming more common as we go deeper in the 21st century, you know, I think it means that people especially need to be weather aware in these regions. You need to be aware of what your high risk days are. You need to know that you have a place to go if you receive a tornado warning, a place to shelter. Not every residential structure is going to be safe in an EF3 or an EF4, unfortunately. So you need to know where you would go if you received a warning. You know, at the societal or at the resilience level, I think we do need to think more and think harder about building codes and building structures that are resilient to 150-160 mile per hour wind gusts. But you know, of course, there's trade offs with that. I mean, those construction techniques are more expensive. So I think it's just we need to be aware that the risk profile is changing. There is a increased frequency of severe tornado activity in these regions of the American south and the east central US, and have that be part of the conversation about what we're building and where.

CURWOOD: Ryan Truchelut is chief meteorologist at WeatherTiger in Tallahassee, Florida. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today, Ryan.

TRUCHELUT: All right. Thank you. Stay safe, everyone.

Links

Scientific American | “Watch Out: Tornado Alley Is Migrating Eastward”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth