April 4, 2025

Air Date: April 4, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Tornadoes in a Hotter World

View the page for this story

Experts are still trying to piece together how tornado patterns have changed in the last century and are likely to keep changing as the world gets hotter. Meteorologist Ryan Truchelut of WeatherTiger joins Host Steve Curwood to explain the eastward shift of tornadoes in the US and how newly vulnerable populations can stay safe. (11:34)

Note on Emerging Science: Orcas Wear Salmon as Hats

/ Kayla BradleyView the page for this story

Orcas in the Pacific Northwest have again been observed carrying dead salmon on their heads. Living on Earth’s Kayla Bradley explains what scientists think this unique behavior may indicate about orcas’ diet, health, and culture. (02:11)

"What I Want to Believe About the Vireos"

View the page for this story

The songbirds called vireos have increased in number by more than 50 percent in recent decades, while birds overall are struggling. That was the inspiration for Poet Laureate of Mississippi Catherine Pierce’s poem, “What I Want to Believe About the Vireos.” She joins Host Jenni Doering to share and discuss. (03:44)

Science and the US Government

View the page for this story

The Trump administration is slashing personnel and research grants at two dozen federal agencies, including those conducting critical science. Science has long played a key role in the federal government, and Naomi Oreskes, a Professor of the History of Science at Harvard, joins Host Steve Curwood to put the recent changes into historical context. (26:19)

Listening on Earth: Cardinal and Robin

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

Two of the most common birdsongs of the New England springtime are those of cardinals and robins. Host Jenni Doering shares a snippet of a recording from her neighborhood and invites listeners to send in their own audio postcards. (01:40)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

250404 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Naomi Oreskes, Catherine Pierce, Ryan Truchelut

REPORTERS: Kayla Bradley

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Twisters are changing with the climate, but science doesn’t know exactly how and why.

TRUCHELUT: So we kind of have this cultural concept of “Tornado Alley” across the plains. But what we’ve really seen in the past 20, 25 years is a shift of the most favored area of severe weather, shifting East, into the Mississippi Delta region, into the Deep South.

CURWOOD: More research is needed but science faces concerning federal cutbacks.

ORESKES: Without science we wouldn't know that it was DDT that had killed the bald eagles. We wouldn't know that it's fossil fuels that are driving climate change. If you don't know what's causing a problem then you can't address the cause, but if you know what the cause is, then you can.

CURWOOD: Plus – celebrating Poetry Month. We have those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Tornadoes in a Hotter World

A tornado looms near Harlan, Iowa. (Photo: Adam Orgler, World Meteorological Organization, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

[Civilian camera footage]

[STORM SFX]

Cameraman: Oh, whoa! Tornado! Tornado, right here!

[ABC News footage]

“In the Midwest and the South, at least thirty twisters reported across six states…”

[NBC News footage]

“A dangerous and deadly outbreak of tornados ripped through eleven states…”

[NBC News footage]

"After a violent weekend of wind, rain, and tornados in the Midwest, more severe weather tonight…”

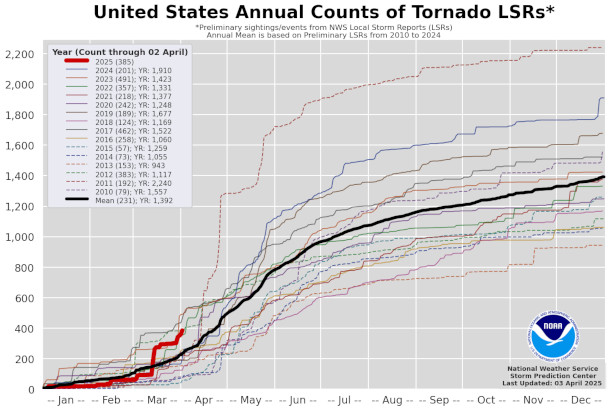

CURWOOD: March of 2025 saw over 200 confirmed tornados throughout the United States, including the largest outbreak on record for the month with a cluster of 116 verified tornados affecting the Midwest starting on March 13th. With all the destruction they can cause, tornados can seem massive, but on a global scale, they’re actually rather small and isolated. Of course, that’s no comfort to those who are affected, but on top of that, it also makes things difficult for the scientists who study them. Experts are still trying to piece together how tornado patterns have changed in the last century, and how they’re likely to keep changing in a warming world. The US has the most recorded tornadoes on the planet, and for why and how we go now to Tallahassee, Florida to meteorologist Ryan Truchelut of WeatherTiger.

TRUCHELUT: Well, the United States really is head and shoulders above other parts of the world in terms of frequency and severity of tornadic activity and severe weather. Of course, you can have tornadoes in other parts of the world, eastern China, South America, all these areas do get tornadic activity and severe weather, but the geography of the United States is particularly favorable for severe weather activity. Basically, that's because of the Gulf of Mexico is a ready source of heat and moisture that flows north into the continental United States, and then there's a large land mass going north into Canada, where you can have very cold air masses develop and then head south. So it's that contrast between the cold, dry air coming in from the north and that warm, moist air coming north from the Gulf of Mexico that's responsible for triggering these severe weather events that are quite frequent in the continental United States relative to the rest of the world. And in fact, the Rocky Mountains kind of being in the west central United States, they act as kind of a natural kind of focusing mechanism for that moisture moving north. And they also act, kind of, from a more technical perspective, as a triggering mechanism for the development of areas of low pressure over the plains that then tend to move northeast and drag fronts behind them. And that kind of all acts as atmospheric precursors to severe weather activity.

When dry air from the Rocky Mountains combines with moist air from the Gulf of Mexico, severe weather can brew. (Photo: G. Lamar, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So Ryan, as I understand it, the link between climate disruption and tornadic activity is not as well understood as, say that, between climate disruption and hurricanes and forest fires. But what do we know on that front?

TRUCHELUT: Sure, well, you know, it's a complex question, and it's something where, you know, we're trying to link changes on a global scale, big patterns of heat and moisture moving around the globe, to something that happens on a very small scale, a tornado or a severe thunderstorm that happens on the scale of a mile or 10 miles. So whenever you're going from that very large scale to the very small scale, it's complicated to do that, and sometimes you get things showing up in the data that, you know, you wouldn't necessarily expect or is a little bit surprising. So we're not really sure that there is a trend in terms of how much tornadic activity or how much severe weather is occurring in the United States generally. We're not sure over the long term with climate change, if that'll trend up or down, but what we do see in the data is there does appear to be a shift in the region where we're seeing severe weather and tornadic activity most frequently. So we kind of have this cultural concept of Tornado Alley across the plains. You know, there's nothing more American when people think about a tornado than a tornado rolling through a wheat field in Kansas or something like that. And of course, we're still seeing plenty of severe weather in the plains, but what we've really seen in the past twenty, twenty-five years is a shift of the most favored area of severe weather, kind of shifting out of the southern plains and shifting east into the Mississippi Delta region, into the deep South, into the Mid-South. So areas like Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, Alabama, Mississippi, these are regions where we really have seen a pretty strong trend towards not only more frequent severe weather and frequent tornadic activity, but also increasing the severity of the tornado activity that does occur there. So I mean, some of the tornadoes that have been the most destructive and the most damaging in recent years, you know, thinking about the Mayfield tornado, kind of cut across that Midwestern region, or kind of southern portions of the Midwest.

A graph demonstrating the count of U.S. tornado reports from 2025 (as shown in red) compared to the last 15 years. (Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So Ryan, when it comes to understanding climate disruption, scientists like to make these models, and they'll look at observations going back decades, even hundreds of years, if they can, and then roll that forward to see what might be happening to the climate. To what extent do we have the data to make such predictions with tornadoes?

TRUCHELUT: I would say that it is the toughest to do so for tornadoes of any of the damaging kind of weather phenomena that we look at. And the reason for that is simply that tornadoes, again, they kind of happen in these small scale, localized areas. And we don't have a great kind of even climatological record of how many tornadoes occurred. Because, you know, if you go back to the 1920s or the 1930s or the 1940s, we have records of tornadoes, certainly, but if a tornado didn't happen near a populated area, or if it was a short lived tornado, we may not have observed it. We may not know that it was there. So the records are quite fragmentary, especially before the 1980s. In the 1980s and 1990s we had the proliferation of more advanced Doppler radar across the continental United States, and that's allowed us to observe a much higher proportion of the tornadoes that occur. So we can trust the last 40 years of tornado data as being relatively free of what we would call observational bias. But really going back before that, we have records of destructive and damaging tornadoes, but we don't really have a good sense of if that number has changed from going 80 years back before the 1950s certainly. So it's tough, whenever you're trying to establish a trend, having a nice, clean, trustworthy data set is paramount. And unfortunately, with tornadoes, just because they're such a small-scale phenomenon, that's, you know, something that's challenging in the field.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about the science that shows that America's tornado hot spot is shifting eastward. What do you make of that?

TRUCHELUT: Well, we're seeing changes that are very notable in the timing of when is the last frost of winter occurring. So you know, if you go back and you look at agricultural records about when we've been planting crops across the southern United States or across the Ohio Valley, we're moving those planting dates forward very significantly, by several weeks over the past 75-100 years. So you know, the people who work with the land, people who work with the environment, you know, they're well aware of these changes that are occurring, because it's impacting their jobs. It's impacting, you know, agricultural practices across the country. So tornado threats and severe weather threats are linked to a contrast in temperature. That shift east, I think it's linked to what times of year that greatest contrast and where that greatest contrast is occurring. So the fact that springs are starting earlier, allergy season is starting earlier, we're planting earlier across the southeastern United States. So the fact that we're shifting that region east, I think, is just a follow-on effect of a changing of the timing of when we're transitioning from winter into spring. And of course, we really have seen that in 2025. There's been several large-scale tornado and severe weather outbreaks already in the month of March. You know, historically, sure, that's something that does happen, but the frequency of it does seem to be increasing over the Deep South and Mid-south.

CURWOOD: Is it fair to say that there were some lollapaloozas of tornado clusters in this spring here?

This home in Rolling Fork, Mississippi was flattened by an EF4 tornado at an estimated windspeed of 190mph on March 23, 2025. (Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

TRUCHELUT: Yeah, I mean, we've seen some outbreaks that produced a lot of very destructive tornadoes. There have been other outbreaks in the past that have produced more tornadoes, but the tornado outbreaks that we saw in March of 2025 really overperformed, unfortunately, from the perspective of EF2s, EF3s, EF4s. And those are the tornadoes that are, winds are 140 or 160, 180 miles per hour. And the force of wind, when you double the wind speed, you don't double the force that wind applies to a building. You quadruple it. So going from the 120 miles an hour wind gusts in a tornado to 180, you're really increasing the damage potential to people's lives and buildings and structures that are unfortunately in the path. So you know that over-performance of severe tornadoes and violent tornadoes unfortunately made some of the outbreaks of the last few weeks quite impactful.

CURWOOD: So Ryan, what kind of predictions do you care to make for this year's tornado season?

TRUCHELUT: Well, I think that we're going to have a pretty active pattern for severe weather continuing for the next six weeks or so. We've had some severe weather threats on the map for early April. We're probably going to go a little bit cooler and drier, maybe for mid-April, but I do think that we'll have additional chances of severe weather in late April and then going forward into early May across the eastern and central US, right in the heart of the new American tornado belt.

CURWOOD: So when it comes to climate disruption, some of the known effects, like hurricanes and storm surge and the fires associated with the drying out, these are things that people can think about and plan for, you know? Don't be so close to the coast. Don't have your house so close to where trees might catch on fire. What advice do you have for people who are concerned about tornadoes? What might they do about their living accommodations?

Ryan Truchelut is co-founder, president, and chief meteorologist at WeatherTiger. (Photo: Courtesy of Ryan Truchelut)

TRUCHELUT: Well, it's a tough question, because tornadoes can happen anywhere. I mean, they can happen along the coast. They can happen inland. You know, we're really looking at questions of: you had a preexisting risk, there was always a tornado threat across Arkansas or Alabama or Kentucky or Tennessee. The fact that these risks may be becoming more common as we go deeper in the 21st century, you know, I think it means that people especially need to be weather aware in these regions. You need to be aware of what your high risk days are. You need to know that you have a place to go if you receive a tornado warning, a place to shelter. Not every residential structure is going to be safe in an EF3 or an EF4, unfortunately. So you need to know where you would go if you received a warning. You know, at the societal or at the resilience level, I think we do need to think more and think harder about building codes and building structures that are resilient to 150-160 mile per hour wind gusts. But you know, of course, there's trade offs with that. I mean, those construction techniques are more expensive. So I think it's just we need to be aware that the risk profile is changing. There is a increased frequency of severe tornado activity in these regions of the American south and the east central US, and have that be part of the conversation about what we're building and where.

CURWOOD: Ryan Truchelut is chief meteorologist at WeatherTiger in Tallahassee, Florida. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today, Ryan.

TRUCHELUT: All right. Thank you. Stay safe, everyone.

Related links:

- The WeatherTiger website

- Scientific American | “Watch Out: Tornado Alley Is Migrating Eastward”

[MUSIC: Little Big Town “Tornado” on Greatest Hits, A Capitol Records Nashville Release, UMG Recordings, Inc.]

DOERING: Coming up, science has held an important role in the federal government since the earliest days of this nation. But now science agencies are under attack. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Bill Anderson, “Whiskey Lullaby (Instrumental)” on The Hits Re-Imagined, TWI Records, Inc.]

Note on Emerging Science: Orcas Wear Salmon as Hats

Orcas have been observed wearing dead salmon on their heads, and researchers posit that behavior may be linked to an abundant salmon season. Pictured above an orca playing in South Puget Sound, Washington. (Photo: Courtesy of Ocean Wise, MML-18)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

In just a moment ‘tis the season for poetry but first this note on emerging science from Kayla Bradley.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

BRADLEY: Trends of the 1980s have made a major comeback in the U.S., from scrunchies to the Tom Selleck mustache. But humans may not be the only creatures who are feeling nostalgic for the 80s. Orca’s have also returned to a fashionable fad of their own- wearing salmon as hats.

In the Puget Sound in 1987, researchers first observed this fishy fashion statement spreading through all pods of the southern resident orca clan. But as quickly as the trend caught on, it faded away. By 1988, orcas seemed to abandon their salmon caps, with no sightings for nearly forty years. That was, until October 2024, when photographer Jim Pasola captured a 32 year old male orca named Blackberry adorned with a glistening salmon hat. Though the orca was not alive during the first phase of the fad, researchers suspect he could have learned the behavior from his older pod-mates… kind of like when my mom gave me her old bell-bottom jeans.

It may sound unconventional to carry your food on your head, but researchers have proposed the trend ties to the abnormally abundant chum salmon season in 2024. Orcas are incredibly intelligent and social, and have been observed to express themselves and their emotions through spy hopping to tail slaps. Perhaps orcas are now taking advantage of their food surplus by playing dress up with their dinner!

Orcas wearing salmon hats? ???? Sounds like the setup to a joke, right? But it’s real. In the 1980s, killer whales in the Pacific Northwest started balancing dead salmon on their heads. And now, nearly forty years later, they’re doing it again. A thread. ???? pic.twitter.com/mTuCbJ2EoU

— Sea Whispers (@SeaWhispers__) December 5, 2024

These hats are a breath of fresh air for the southern resident orcas of Puget Sound, who have been endangered for several decades, with only around 70 whales today across the clan. No one knows how long this fashion trend will last this time around or if it’s spread beyond Blackberry’s photoshoot. Will it be as persistent as the fanny pack, or will it get left behind with leg warmers? Either way, its a good reminder that we are more alike other animals than we think- even those who are forty times our size, sixty feet deep in our oceans.

For Living on Earth, I’m Kayla Bradley.

Related links:

- Scientific American | “For Orcas, Dead Salmon Hats Are Back in Fashion after 37 Years”

- National Geographic | “Why These Orcas Are Wearing Salmon as Hats (Again)”

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

"What I Want to Believe About the Vireos"

A vireo perches atop a twig. (Photo: yuki_alm_misa, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: April is Poetry Month, and one of our favorite poets here at Living on Earth is Catherine Pierce. She teaches at Mississippi State University and is just wrapping up a four-year term as Poet Laureate of Mississippi. Many of her poems touch on ecological wonder, joy, loss, and grief. And in this poem about vireos, Catherine muses about their surprising resilience. While North American birds overall have declined roughly 30 percent since 1970, mostly due to habitat loss, invasive species and predation from cats, vireo populations grew by more than 50 percent since then.

PIERCE: I’m Catherine Pierce, and this is my poem, “What I Want To Believe About The Vireos.”

The vireos are plotting.

They are everywhere and various

and all with names

like Shakespearean villains

disguised as Shakespearean clowns.

Black-whiskered.

Plumbeous. Slaty-capped

shrike. Their songs drop

from the canopy like candied

needles, and everyone smiles. Sweet

birds. They’ve been above us

for centuries, watching. See

their eyes: small bright

pebbles that betray

nothing. They know

patience. See them tableau’d

on the oak branch

for minutes before diving

for the fat black beetle.

They know how green works,

how it muscles back, always,

once the pillars and poisons

are gone. They’re playing

the long game. Weary,

weary, weary, trills the scrub

greenlet. It’ll all be theirs

again—rain forests, mangroves,

the great deciduous rustle.

The breeze and moss.

The loam and sunrise.

The vireos will be here

at the end and at the next

beginning. The red-eyed

vireo’s call will sound then

like it does now, like

it’s constantly asking

and answering

its own questions.

What did they do?

They did.

What did they know?

They knew.

Catherine Pierce is the author of four books of poems including Danger Days and The Tornado Is the World and is professor of English and co-director of the creative writing program at Mississippi State University. (Photo: Megan Bean / Mississippi State University)

DOERING: They seem to have such agency in this poem, as you imagine it.

PIERCE: Yeah, I wanted to sort of give the birds credit. I was imagining this as they're playing the long game, as it says in the poem. They see the destruction that's being kind of brought to their habitats. And they're, they're playing the long game, they're going to wait it out, they're going to stick around. They imagine that eventually humans will kind of... they'll kind of eradicate themselves, and then all the green will come back and all the birds will come back. And so it's, it's a bleak fable, but it's only bleak for the humans. I think it's really good for the birds.

DOERING: And what about us? Are we playing the long game, do you think? I don't get that sense from your poem.

PIERCE: You know, I mean, I think that this poem is, you know, and I wrote this several years ago, and things seemed maybe even bleaker than they do now. So I think it's good that I don't know that I would have necessarily written this poem in the same way, if I wrote it now. I do have a little bit more hope now that some things are changing, that some policies are getting better. I think some people are playing the long game. I don't yet think enough of us are playing the long game for thinking about sort of, you know, sustaining this planet, the only planet that we have. But I think that more and more people are beginning to think that way. And I think that more policies are beginning to change. And so I'm hopeful, I'm cautiously hopeful that maybe we'll be moving more toward that as time goes on.

DOERING: That’s Catherine Pierce, poet Laureate of Mississippi. Her latest book is called Danger Days.

Related links:

- Catherine Pierce’s website

- Find Catherine Pierce’s book of poetry, Danger Days, here (Affiliate link supports LOE & indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Andrew Gialanella, “Elevate” Single, Andrew Gialanella]

Science and the US Government

The Trump administration has so far cut tens of thousands of jobs from over two dozen federal agencies, including many dedicated to science. The “Stand Up for Science” rallies have protested these cuts. Shown here is the D.C. rally held on March 7, 2025. (Photo: Geoff Livingston, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: A lot more scientific research is needed before forecasters can predict the power and paths of tornadoes days in advance, the way the public gets warned days ahead about hurricanes, but tornado science is just one avenue of research now endangered by the Trump Administration. The president and his people are slashing personnel and research grants at two dozen federal agencies, including ones conducting critical science. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration or NOAA and the National Science Foundation lead federal climate and weather research and already 10% of their staffs have been fired. Science to support human health is also getting cut with 10,000 layoffs underway at the Department of Health and Human Services or HHS. And many of their grants have been paused or rescinded, including $12 billion to help states track infectious diseases and other health issues. On March 31, over 1900 researchers signed an open letter to the American people calling for the Trump administration to “cease its wholesale assault on U.S. science” and for the public to join its plea. For some historical context, we turn now to Naomi Oreskes, professor of the History of Science at Harvard University. With Erik Conway, she coauthored the 2010 book Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming and the 2023 book The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Naomi!

ORESKES: Thank you. It's always a pleasure to be with you.

CURWOOD: Professor, you're an historian of science. So when did this question of science's role in the US federal government first arise here?

ORESKES: Right from the beginning. So we know there were actually big arguments during the early years when the founding fathers were thinking about the new government, and there was actually a fairly spirited debate about whether or not there should be a science department in the new government. And Thomas Jefferson really wanted that, but many of his colleagues didn't, because they felt that science was an elite activity that should be sponsored and funded by societies like the American Philosophical Society, which already existed and it wasn't a function for government. But interestingly, even though Jefferson lost that debate, very quickly, within just a few years, people began to realize that the new government needed science.

CURWOOD: So what was the catalyst for creating the first few federal scientific agencies when they did come along, and what were their functions?

The first federal scientific agency, the US Geological Survey, was established in 1807 to create accurate maps. The above map was published by the agency in 1890. (Photo: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

ORESKES: The first federal scientific agency was the US Coast Survey, later renamed the US Coast and Geodetic Survey. Thomas Jefferson was still president in 1807. And its function was to make accurate maps of the coastline because people quickly realized that you need science for commerce, because you need accurate maps. And shipping, of course, was the most important way that goods came in and out of the country. And so if you didn't have accurate maps of the coast, ships would wreck, and huge amounts of material would be lost, lives would be lost. And people realized it was actually impossible to have an economy without accurate maps, and it was impossible to have accurate maps without science.

CURWOOD: So fast forward to the 1970s, we saw, really, I think, an explosion in the establishment of several landmark scientific agencies. I'm thinking of the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. What was going on politically and socially at that historical moment to kind of push our government in the direction of paying more attention to science?

ORESKES: Well, I'd say the short answer was the rise of the environmental movement and the increasing recognition that industrial activity did damage, did damage to the environment, did damage to species, like DDT killing the bald eagle, and also hurt people, damaged people's health. And so as the scientific evidence for physical, emotional, mental and health harms from industrial activity got stronger and stronger, there was more and more push to create agencies that would deal with those harms. And the Environmental Protection Agency, of course, is the most famous and most important and a big part of that story involves DDT. So after Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring, that book got a lot of attention, both popular attention, but also political attention. We know President John Kennedy talked about the book. So Carson showed that DDT and other persistent pesticides were doing very radical harm to the bald eagle, to other birds, to fish, that she wrote that book based on extensive scientific work that had already been done by government scientists, particularly scientists in the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and also scientists in state Fish and Game agencies. What she really did was to compile all that diverse data, put it together in a powerful, well written story. Got a lot of attention for it, and especially this recognition that DDT was killing the bald eagle, the symbol of this country, not the turkey, which we know Ben Franklin wanted, that and the potential for harm to people was really galvanizing. And so the environmental protection agency was created to look into the science regarding harms, like the harms created by pesticides, and to create a foundation for rational regulation of dangerous materials in the environment.

CURWOOD: And of course, you get Earth Day in 1970 with fire on a river outside of Cleveland, the Cuyahoga River fire. To what extent did that help catalyze the federal government's interest in science because I think the man who actually is president when the EPA is formed is Richard Nixon.

The 1962 publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, which documented the hazards of DDT, galvanized the public to demand more protection from industrial activity. (Photo: GPA Photo Archive, CC BY 2.0)

ORESKES: It shows how much our politics have changed. So in addition to the DDT story, there were a number of additional galvanizing events in the 1950s and 60s. One was the Cuyahoga River, which, as you just mentioned, caught fire. There was also the thermal inversion in the town of Donora, Pennsylvania, where I believe it was thousands of people, residents, including children, were killed when toxic air pollution settled on the town. And then there was also the smog in Los Angeles and in London. And again, people literally dropped dead in the streets during the London smogs and the fact that people were dying in real time. So this wasn't just the possibility of cancer that might kill you 20, 30, 40, years later, but this was people dying acute injury from air pollution. And so these different events in different places across the United States and the world were really galvanizing for people to say, no, it's not okay for companies to just dump toxic pollution in rivers, in lakes, in the atmosphere and kill people. And so you saw increasing bipartisan political support, so much so that, as you say, Richard Nixon, who was not a great environmentalist, but recognized that pollution was a really important issue to the American people, that the American people wanted this, and so he signed the legislation that created the Environmental Protection Agency.

CURWOOD: So what happened? Why did federal scientific agencies slip from being bipartisan deals to being very partisan deals?

ORESKES: The short answer is industry pushback and industry disinformation. So almost as soon as the ink is dry on the National Environmental Protection Act, which created the EPA, there's pushback from industry, and industry begins to argue, the country is becoming over regulated. You know, we can't operate. This is going to kill our businesses. And so they begin to organize in a number of different ways. One of the things that you may have heard of is the so-called Powell memo. The idea was to galvanize the business community to fight back against environmental regulation or any other regulation that they felt tied their hands. So it included regulations about labor laws, workplace safety. And so you see this building hostility towards government regulation of the workplace, government regulation of pollution, which then becomes increasingly expressed as an attack on the science that explains the need. And we see that really take hold in a big way with the election of Ronald Reagan. It's in the Reagan administration where we first begin to see organized resistance to scientific evidence that proves that something is doing real harm, and therefore that it might be reasonable to regulate that substance or that activity.

In the 1970s and 80s, Exxon Mobil’s own scientists warned the company about the consequences of burning fossil fuels. In response, Exxon, along with many other fossil fuel companies, engaged in disinformation campaigns to discredit climate science. (Photo: Mike Mozart, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So this is the same period of time, Professor, that Exxon's own scientists were telling the company that, guess what, burning this fossil fuel is going to warm the planet in really uncomfortable ways. Hmm. So business learns that this is not good for the planet, but yet they push the political process to make it okay for them to go ahead and ignore the science? It feels like I'm reading this wrong.

ORESKES: No, I'm sad to say you're reading it exactly right. The evidence is quite overwhelming that we know that when we look at the climate change issue specifically, but other issues as well, that in the 1960s, 70s, and well into the 1980s, the American fossil fuel industry, and actually the fossil fuel industry overseas as well, was quite well aware of the emerging scientific evidence that burning fossil fuels produces greenhouse gasses, particularly carbon dioxide, that these gasses heat the atmosphere, and by heating the atmosphere, they heat the planet, and that in time, the planet would heat up and this would have really serious consequences. We know that one company in particular, ExxonMobil, even had a large research program in the 1970s and 80s to investigate this more closely. And we know that their own scientists not only did excellent, high quality scientific work, which in a few cases, they published in peer reviewed journals, but we also know that those scientists informed their managers about this problem, and in some of their reports and memos, they even say that this could be potentially catastrophic. And here's the really, you know, what I see as almost Shakespearean tragedy, because of the stakes were so high that the company made a decision around the late 1980s to stop doing science and to start funding disinformation.

CURWOOD: There's a scientific issue that comes up in this period of time around tobacco and its deleterious effect on human health, and you've written a fair amount about that. What did America's experience with tobacco tell you in terms of how we went so far down that dark hole of having people smoke, and how hard it was to dig us out of that? But it was done.

ORESKES: It was, but it was very hard, and it took a very long time. As you say, one of the things I've worked on is the history of the role of the tobacco industry in denying scientific evidence and attacking science and fostering public distrust of science broadly as a means to try to protect its product, tobacco, from regulation or even bans. What we saw in the tobacco story, and then again, more recently, in the fossil fuel story, is that there are corporations that are so committed to the profits that they make that they will defend their product even in the face of overwhelming scientific evidence that these products are doing huge harm. And in the case of tobacco, even though everyone knows the tobacco story, I think many people still don't really quite realize how incredibly harmful this whole industry was. So the World Health Organization has recently estimated how many people died in the 20th century from diseases caused by tobacco use. And the number is 100 million. 100 million.

CURWOOD: Uh, that's a big number.

The tobacco industry denied scientific evidence to protect its product. (Photo: Philip Morris Company, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

ORESKES: That is a big number, more than died in all the world wars in the 20th century. I mean, just for comparison, something, over a million people died here in the United States from COVID. And think about how the COVID pandemic upended our lives. And this is 100 times that.

CURWOOD: We’re speaking with Naomi Oreskes, professor of the History of Science at Harvard University, and we’ll be back in a moment with more from our conversation. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

[MUSIC: Floodplain, “Twilight” Single, Floodplain]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Floodplain, “Twilight” Single, Floodplain]

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. We’re back now with Naomi Oreskes, professor of the History of Science at Harvard University.

CURWOOD: So Naomi, we're talking to you today because many people have been, in some cases, shocked by the ways in which the Trump administration has undermined science and its role in our government. So give us an historical perspective. To what extent are the Trump administration's attacks on science unprecedented? Which actions are really setting up the loudest alarm bells for you, and which feel more like parts of you know, a predictable political cycle?

ORESKES: Well, it's a tricky question, because I think, as you just suggested, it's both and. So there have been questions about the role of science in the federal government, as we started this conversation, right from the very beginning of the nation. And certainly in the 19th century, as we saw the expansion of federal science, the creation of additional scientific agencies like the US Geological Survey, there were always questions raised about, is this an appropriate use of taxpayer money? Is this an appropriate federal function? And there have been times when people have pushed back and said, no, this is going too far. But I would say that in the past, those were always done with at least some respect to factual information. What's different about this, I think, is it's a kind of wholesale attack on science and indiscriminate. And we've seen in recent weeks, you know, massive firing of people without cause. It's not like there's been any kind of review of these agencies to say, what are they doing well? What are they doing poorly? No, there's been no review whatsoever. And I think this tells us this is not about a principled question about the appropriate role of federal authority, or how to make these agencies function more efficiently. This is a wholesale attack on the federal government, and federal science is part of that. But it's not just a part. It's a very important part, because of the role of science in informing regulation. And we know that the right wing that is now in charge of the Republican Party, they hate regulation. They hate the idea that the federal government would restrict their activities in any way. And we've seen Elon Musk even say publicly, if it were up to him, he would eliminate all regulations.

Naomi Oreskes acknowledges that while there have always been questions about the role of science in the federal government, she sees the Trump administration’s rollbacks as an indiscriminate attack on science. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Naomi, to what extent is this all about the money?

ORESKES: Yeah, Steve, I get that question all the time, and I really think it's not just about the money. I mean, money is clearly driving a lot of this, and we know that companies like ExxonMobil, Philip Morris Tobacco before them, have been among the most successful, profitable companies in the history of mankind. So money is clearly a huge part of the story, but I actually don't think it's only about money. I think it's also about power and it's about prerogatives. One example I always like to use is seat belts. When the federal government mandated seat belts, the auto industry cried bloody murder, said this will bankrupt us. Customers will never pay for this. Well, here we are, sixty years later. We all have seat belts. Nearly all of us use them. So there's a lot of overreaction by industry to the economic pressure that regulation imposes. So what's really going on there? I think it's about power and prerogative. I think a lot of these business leaders, and I think Musk is a case in point, they think that they should have the right to do whatever they want. And I'd say a generous interpretation would be they think, we have the right to run our businesses as we see fit, and we know better than the government how to run a successful business. That's the charitable interpretation of it. The uncharitable interpretation is, who the heck is the federal government to tell me what to do? And there's a kind of anger that you see in some of the rhetoric, anger at the idea, the very idea that anyone else, whether it's Washington DC, a labor union, consumer activist, that anyone else should have the temerity to tell these people that they don't have the right to do whatever x is, whether it's to dump air pollution in the atmosphere, to exploit children in factories. And we see this, so in the new book, we document how these arguments played out over the course of the 20th century. And it's so interesting to see how the same arguments come up over and over again about defending the right of businessmen. And I use the word men deliberately, because they almost always were, the right of businessmen to run their businesses as they see fit and not have the government telling them what to do.

CURWOOD: So what about the argument that science should just be left to the private sector? I mean, now we have a private company, for example, doing our space exploration.

Modern space exploration was made possible by decades of investment in federal science. (Photo: Scott Andrews, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

ORESKES: Well, I think history proves that that just doesn't work. I mean, yes, the space program is actually a case in point, because we are at a point in history where we can have private space exploration. But what made that possible? Half a century of huge public investment. And if you go back to the early period of the space program, back, you know, right after World War II and into the 50s, there was no private company that was going to take the risk of trying to develop space going missiles. And so there were decades when all of the risk was taken by the federal government here in the United States, later the European Space Agency in Europe, also, obviously, the Russians had a massive and successful space program. So all of that early risk, all the early science and engineering, the technological innovation, was all done by the public sector. And one of the things we know from history, and there's a very excellent book on this, written by Mariana Mazzucato, economist in Britain, called The Entrepreneurial State, where she makes the point that the claim that business people make very often, that they love risk, that they're the bold risk takers, history really shows that is really often not the case, and that in many, many cases, if you look closely, what you see is it's actually the public sector that takes the initial risk, lays the foundation that then makes it possible, subsequently, for the private sector to move in. So without public funding of science and engineering, we would have no space program. And the same is true of the internet. It was the government, or I should say, government scientists, scientists funded by the US federal government, who invented the internet. It was called DARPANET, and it was originally developed as a communications system for the military. All of the initial work for that was done by scientists funded by the federal government. And although Al Gore did not invent the internet, he did sponsor the legislation that made it public and that made it possible for Silicon Valley entrepreneurs to then develop the whole universe of internet applications that we have today, but none of that would exist without public funding.

CURWOOD: What do you think are the consequences of shrinking the role of science in government? I mean, what's at stake?

The foundation for today’s internet was created by government scientists as a communications network for the US military. (Photo: Caio, Pexels, Public domain)

ORESKES: Well, I think many things are at stake, but the two most obvious ones are public health and safety and the natural environment. So many of the federal agencies that we have today, groups like the CDC, Centers for Disease Control, the National Institutes of Health, do scientific work on behalf of human health and safety. And just to give one example, the messenger RNA vaccine that was developed during COVID that is now protecting, I don't know some 250 million Americans or more, that was developed in the private sector, but it was based on research that was largely done at the National Institutes of Health. And if we hadn't had that scientific foundation to build on, there's no way that a vaccine could have been produced in just one year. So I think we would really see the United States lose its leadership in public health and medicine, and I think that that would have very direct consequences in people's lives. The other obvious big area is the natural environment and climate change, and this is a little harder and trickier when we get into climate change, because so much of my work has been about how the science has been ignored. So I can't say that having the science will change things if we've witnessed 30 years of ignoring science, but certainly in many, many areas of environmental protection, having to do with air pollution, water pollution, plastics in the environment, the impact of pesticides, the regulatory structures for protecting people from these dangerous products and activities is based on science. Without science, we wouldn't know that it was DDT that had killed the bald eagles. Without science, we wouldn't know that it's fossil fuels that are driving climate change. I think about this a lot, like, what role does science really play? So imagine there had never been any climate science. We would all realize the climate was changing. I'm speaking to you from Australia, where it's incredibly hot and dry right now, but without science, we wouldn't know why. So science answers the why question and the why question is urgent and essential for the solutions, because if you don't know what's causing a problem, then you can't address the cause, but if you know what the cause is, then you can.

The development of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine was also supported by federal research. (Photo: Spencerbdavis, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

CURWOOD: So there's a perception that a large part of the public distrusts science these days. How true is that and how might we reinstill trust in science?

ORESKES: Well, I'm glad you asked that question, because actually there's a little bit of good news here. There have been many polls, the Pew Research Foundation are particularly good on this, but there are other polls as well, and these polls consistently show that the vast majority of Americans, something like 70% still have a high level of trust in science, and scientists, still think that science as a whole, as an enterprise, makes our lives better, and believes that the federal government should support research in both science and technology. So what's that famous line about rumors of my death are premature? The rumors of the death of science or the end of science are definitely premature. And I think it's really important here not to overreact, because we don't want to be estranging ourselves from a public that, in fact, largely supports us. But I do think that two things, in any area of life, you don't want to take trust for granted, and so it is really important for the scientific community to continue to think about what kinds of activities can we be engaged with to help maintain and expand that trust, whether it's public education, support for informal education through museums or aquaria, or just individual scientists going to schools and churches and synagogues. I think a lot of scientists still feel like that's not my job. I don't have time for that. And I think that the last few years have really shown us we have to make time for that kind of work, and we have to consider it part of our job, because when we don't, we do risk losing the trust of significant numbers of our fellow citizens. And this is the really key part, even if 70% of Americans trust science and want the government to fund it, 30% who don't is still very significant, because if those 30% are unvaccinated, or even if 10% are unvaccinated, then we begin to see what we're already seeing in Texas. No one should have measles in the 21st century. And yet, we have seen people now dying of measles, a completely preventable disease, because they don't trust the vaccine. And so even if the percentage who reject science are small, those small percentages can have very serious, in some cases, even deadly impacts.

Naomi Oreskes is a professor in the History of Science Department at Harvard University. (Photo: Kayana Szymczak)

CURWOOD: What's going to be the international impact of the US government being so hard on science, both blocking the results and the information coming from science when it comes to stuff like the climate and toxics, but also in terms of educating the next generation of scientists?

ORESKES: Well, that's a great question, and in a way, there's a bit of a silver lining here, because there are great and talented scientists all across the world doing important work. So you know, if the United States creates a vacuum, other countries will step up to fill it, and I think science as a whole will continue. I don't think the scientific enterprise will collapse just because the United States withdraws or lessens its commitment. But at the same time, I don't want to just say it'll all be fine for that reason, because the United States has played a really crucial role, particularly in terms of data sharing, especially satellite data, but also in climate change, helping to run the Model Intercomparison project at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. The United States has really been a leader in terms of data collection, data curation and data sharing, and that's crucially important for the advance of scientific understanding. So I think there's no question that if we abdicate responsibility, other people will step up to the plate, but it will take time before they can really make up for the losses that the United States is now creating.

CURWOOD: Naomi, what can you give us in the way of hope? To what extent can we learn from the past?

ORESKES: Well, I wouldn't be a historian if I didn't think we could learn from the past, and I certainly wouldn't be a professor if I didn't think we could learn from the past. I think one of the key things that the history of science and the federal government shows is how repeatedly, over the course of the history of this nation, people have recognized the need for science in many diverse ways, and whenever people have pushed back and said, oh no, we don't need it, it's not a federal function, the side that won the argument was, yes, we do need it, and it is a federal function. And I just had the opportunity here in Australia to share a stage with Kumi Naidoo from South Africa, who's an amazing, inspiring speaker. And one of the things he said a few days ago was, pessimism is a luxury that we do not have, and I like that. You know, there's a lot of reasons to be frustrated right now, but at the same time, there's also a lot of work to be done. And so I guess my grounds for hope is sort of simply that we have to work. We have to get back to work, and when we face problems, Americans are actually very good at rolling up our sleeves and getting to work. And so I guess I have some degree of optimism in Americans' appetite for hard work, Americans appetite for challenge, and to know that, you know, we've been through tough periods before, and we will get through this tough period as well, I think, I hope.

CURWOOD: Naomi Oreskes is a professor of the history of science at Harvard University. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

ORESKES: You're welcome. It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Read 1900 Researchers’ Open Letter to the American People

- The New York Times | “What We Know About Cuts to the Federal Work Force”

- Read more about Naomi Oreskes

- Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming

- Bloomsbury Publishing | The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market

[MUSIC: Mansur Brown, “Mashita”, on Shiroi, Black Focus]

Listening on Earth: Cardinal and Robin

Male cardinals like this one can really belt out a tune any time of year, but spring is peak showtime. (Photo: Carolyn Lehrke, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

[CARDINAL CALLS]

DOERING: On the first day of spring, I went for a walk in my Watertown, Massachusetts neighborhood at dusk. A brilliant red male cardinal sang from a power line.

[CARDINAL]

DOERING: Then it was a robin’s turn to solo.

[ROBIN]

DOERING: I’ve heard their songs many times before, and they always bring a smile to my face and clear the winter blues away.

[CARDINAL AND ROBIN]

DOERING: I captured these familiar sounds of spring on nothing more than my circa 2017 iPhone, and you can too! So, what catches your ear when you’re out in nature? Or maybe, what catches your eye when you see who or what is living on earth? Share those sounds and thoughts with us by pressing record on Voice Memos, Voice Recorder or any other smartphone recording app. You can walk and talk but also be sure to stand still for at least two minutes, without talking or fidgeting, to get the best quality of the sound of your environment. After you have those two minutes or more of ambient sound, please hold the phone up near your mouth and clearly tell us who you are, where you are, and why you want to share this moment with us. Then you can email us the file at comments at loe dot org, and we might just use your audio postcard on the air! That’s comments at loe dot org.

Related links:

- How to make a sound recording on an iPhone

- How to make a sound recording on an Android

[CARDINAL]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, scientists are gazing at the clouds from space to understand what’s happening to our climate.

FRANCIS: Clouds are beautiful in one sense. I mean, we love looking up and, and seeing patterns in them. We love what they do to our sun rises and sunsets. We depend on them for rainfall and snow. And yet, there's this other side of them that they have a really important role in the Earth's climate, and they're one of the hardest things to figure out in terms of how the climate has changed and will change, and that is because they have this dual role of reflecting heat from the sun but also trapping heat down by the earth surface. And so for us climate scientists to try to figure out how they're going to change in the future, what their role is going to be in terms of either making global warming worse or perhaps offsetting it somewhat, it's probably the biggest source of questions that still exist in our ability to look forward and try to figure out how the climate system is going to change.

CURWOOD: That’s next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Kruger Brothers, “Up 18 North” on Up 18 North, Double Time Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Daniela Faria, Mehek Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti McLean, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Frankie Pelletier, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and You Tube music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. We always welcome your feedback at comments@loe.org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth