Shrinking Clouds

Air Date: Week of April 11, 2025

Cloud cover has been shrinking over the last 20 years, according to an analysis of NASA satellite data. (Photo: NASA Johnson, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In terms of physics, global warming comes down to an energy imbalance as Earth is taking in more energy than it is releasing. A new study suggests that shrinking cloud cover is playing a big role in that imbalance. Jennifer Francis, an atmospheric scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center joined Host Aynsley O’Neill to discuss.

Transcript

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

When we talk about global warming, the evidence is overwhelming. Simply put, more energy enters the planet than leaves it, and the majority of this imbalance is tied to our greenhouse gas emissions. Much of the rest can be tied to shrinking ice coverage, which exposes darker ground that absorbs more heat. And paradoxically, cleaning up our polluted air does the same, since the toxic haze of airborne fine particles and aerosols reflects light and stops it from hitting the earth’s surface. But altogether, there has still been an unexplained gap in earth’s energy budget. So, NASA scientists now believe that they’ve found the missing piece. Using satellite data, they calculated a reduction of reflective cloud cover by at least 1.5% in the last 2 decades. That might seem like a small amount, but it adds up quick. And this time, it’s not fed by the pollution paradox. 80% of the reflectivity changes were caused by shrinking clouds, instead of the darker, less-polluted hazes. Jennifer Francis is an atmospheric scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, and she joins us now to explain this recent study.

FRANCIS: Clouds are beautiful in one sense. I mean, we love looking up and… And seeing patterns in them. We love what they do to our sunrises and sunsets. We depend on them for rainfall and snow. And yet, there's this other side of them that they have a really important role in the Earth's climate, and they're one of the hardest things to figure out in terms of how the climate has changed and will change, and that is because they have this dual role of reflecting heat from the sun but also trapping heat down by the earth surface. And so for us climate scientists to try to figure out how they're going to change in the future, what their role is going to be in terms of either making global warming worse or perhaps offsetting it somewhat, it's probably the biggest source of questions that still exist in our ability to look forward and try to figure out how the climate system is going to change.

Clouds function differently in various parts of the planet. For example, clouds covering stretches of bright white ice would absorb and release heat differently than clouds covering swaths of dark blue ocean. (Photo: Jeremy Stewardson, Unsplash, Unsplash License)

BELTRAN: So, Jennifer, what did this study find?

FRANCIS: So, the main finding is sort of clearing up something no pun intended, that has been a climate controversy for quite a while, and that is whether changes in clouds are causing warming to become warmer, or whether they're reducing the warming. And what this study basically found is that indeed the changes in cloud cover are causing the warming to be even stronger. So, this is another really concerning vicious cycle, one of many in the climate system that make the initial warming even more than it would be otherwise.

BELTRAN: And how was this study conducted? You know, what tools did researchers use to come to that conclusion?

FRANCIS: Yeah, so the main tool that was used was measuring clouds from satellites. And satellites can measure various wavelengths of energy. You could think of it as different wavelengths of light, but some of that light we can see, and some of it we can't, and clouds affect these different wavelengths differently. And of course, there's many different kinds of clouds, which makes it so complicated, because some clouds are made of water droplets. Some are made out of ice particles. Some of them are high up in the atmosphere. Some are low. And so, sorting out all the ways that clouds are changing and how they're affecting the heat that's absorbed or released by the Earth is not straightforward. So, the first things you have to do in a study like this is try to measure these different kinds of clouds, make sure you know what you're seeing from outer space, and then being able to detect how they might be changing over time. And I can tell you from my own work that it is not easy, because it depends on many things. These changes in clouds, it depends on what's underneath them, whether it's ocean or land or snow or ice, and all of those things really complicate these measurements, but having many different wavelengths of light that you can measure helps you sort out some of these differences, and that's what these researchers have been able to do. And what they were looking for was mostly changes in the coverage of these different types of clouds and using these satellite measurements of different kinds of light, that's what they were able to do.

A layer of fog blankets Mill Valley, California. Jennifer Francis notes that clouds off the coast of California tend to spread out in a uniform manner, appearing very bright and white to a satellite. (Photo: Zetong Li, Unsplash, Unsplash License)

BELTRAN: And how big are these changes to both the size of the clouds and the movement of the clouds?

FRANCIS: Well, they're not very big really. They're on the order of a couple percent. 2% doesn't sound like much, just like warming of the earth by 1.5 degrees doesn't sound like much, but it's having a big effect. So, one other important piece of information is that clouds do two things. They reflect sunshine, so that's a cooling effect. If there are more clouds, then they reflect more of the sun's energy back to outer space. But clouds also act like a blanket, so they also trap heat, just like greenhouse gasses do, and so there are these competing effects that clouds have. So that was the other part of this study that makes it so complicated is you have to figure out whether any change in clouds you're seeing is having a net cooling effect or a net warming effect, and where those clouds are located and how high they are in the atmosphere and what they're made out of, affects that distinction.

BELTRAN: Well, not all clouds are created equal, right? So how much are complicating factors like cloud type or color making an impact here?

FRANCIS: Yes, so cloud type has a huge impact. The clouds that are made out of water droplets versus ice particles have a much stronger influence on the energy that is either trapped or absorbed at the surface. So, let's talk about a couple different cloud types. One is the sort of very layered clouds that we see in various parts of the ocean. You could think of off of the California coast, where the clouds tend to be very uniform and spread out in a layer. And if you looked down from a satellite, they would look like a very bright white object. So they are very good at reflecting sunlight back to outer space, and when they're missing, if that amount of cloud of that type is much smaller, then it's going to let a lot more of the sun's energy into the ocean, and that ocean underneath is very dark, so it absorbs almost every bit of that energy that the clouds either let through, or if they're missing, that hits the ocean surface. If that same kind of cloud was sitting over a snow field, say, it's a totally different story, because that surface underneath is already very white, and so it's really hard to see those clouds actually from a satellite, because the cloud is white, the snow is white, and it's really hard to tell the difference. So, when it comes to heating, it also doesn't make as big of a difference, because if you lose those clouds over snow, you're still going to reflect most of that energy right back to outer space. So not only does it matter what kind of cloud it is, but it also matters what that cloud is over.

BELTRAN: And what could explain the drop in cloud cover just far as we know?

Extreme heat and weather events are worsening, and the ongoing reduction in cloud coverage is only feeding into that pattern. (Photo: Athena Sandrini, Pexels, Pexels license)

FRANCIS: Well, there's many things that can affect the amount of cloud that's there. So, one would be just to have a smaller area of cloud because of how the winds are moving those clouds. Some clouds are formed by two wind currents meeting and then having that wind have to go up. And so, you can think of the belt around the equator that we call the inter tropical convergence zone. It's where the two trade wind systems meet and where they collide. So, these winds come together. It means that the air can't go down, because the Earth is there, so it has to go up. And when air goes up, it eventually will cool off enough so that the water vapor in that air will condense into a cloud. So, if those wind currents that cause those clouds to form changes somehow, it could cause that area of those very turbulent, convective, puffy clouds that you see in the tropics often, that belt could get smaller, or it could get wider. And so, this study has suggested that that particular belt around the equator is, in fact, getting narrower, and so those very bright white clouds that happen in the tropics, especially over the dark ocean, if those get smaller, then they're going to reflect less of the sun's energy, and more of that heat will go into the ocean.

So, wind currents is one thing that can happen, but it can also be changes in the temperature structure of the atmosphere. So, it's how temperature changes as you go up into the atmosphere. Generally speaking, it gets colder as you go up. And if you've ever flown in an airplane that isn't pressurized, you'll know that it gets colder as you get up there, but the rate of that change of temperature can also change. And so that point where water vapor, which is the gaseous form of water that's in the air all around us all the time, at some temperature, that water vapor will start to condense into little droplets, which is what we see as clouds. And so, anything that affects that temperature distribution in the atmosphere going up is also going to determine whether the clouds form sooner or form later as air goes upward. And that air could be pushed upward by a storm system, or it could be pushed upward by mountains. So, there's a lot of different ways that air is pushed upward to create clouds.

Jennifer Francis is a Senior Scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center. (Photo: Courtesy of Jennifer Francis)

BELTRAN: So according to this paper, global cloud circulation patterns are changing. What impacts can we expect to see in the next five or the next 10 years?

FRANCIS: Well, unfortunately, it means that the warming that we've already been observing in the last couple years were the warmest on record for the earth, probably going back 120,000 years, which is very disturbing all by itself. But this just means it's going to be even harder to turn this around or to slow the warming, which is exactly what we have to do, because we've already seen the cascading effects of what this warming is doing. We're seeing increased heat waves, which is the most direct connection between a warming globe and extreme weather events. We've seen longer lasting, more intense droughts, wildland fires and urban fires, and we've seen those in spades the last few years. And we're also seeing increased flooding events and heavy precipitation events that can lead to flooding, and that is because that warming air absorbs more water vapor, so when a storm does come along, it has more water to work with. I mean, all of these extreme events that have been happening more frequently, we're going to see that become even worse as the globe continues to warm, and part of that story is the reduction in these very bright, white clouds.

BELTRAN: We're chatting now at a time where a lot of national science agencies like NASA and NOAA are facing personnel and budgetary cuts from the Trump White House. How are you feeling about the future of scientific research in light of these cuts?

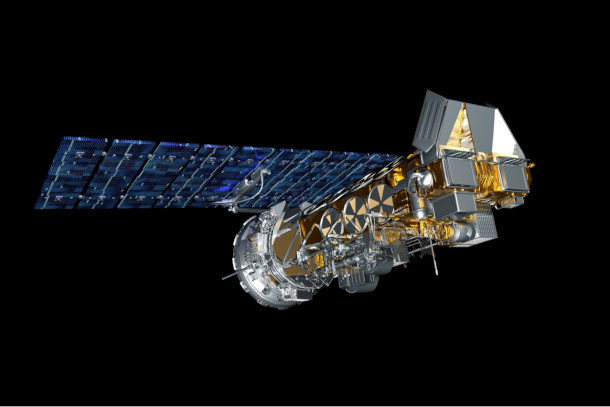

Shown here is a computer rendering of a TIROS N satellite, likely NOAA-18. Satellites operated by government agencies like NASA and NOAA provide crucial data for meteorologists, climatologists, and other researchers. (Photo: NOAA NESDIS Environmental Visualization Laboratory, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

FRANCIS: Yes, well, the cuts have been threatened. I mean, people have been let go. The cuts to funding have not really materialized quite yet. There's certainly a concern, because all of the good work that the National Weather Service, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, that's NOAA, NASA, I mean, the satellite observations that were used in this study to understand these changes in clouds came initially from satellites that were developed by NASA, and once that technology is proven, then usually NOAA takes over the maintenance of those satellites and the data that they collect, and then the scientists that work at NOAA and the National Weather Service in NASA figure out how to interpret those satellite observations and turn them into information that really matters to all of us, things like, how much worse is the climate crisis going to get? Where are these storms happening? All of that is the kind of work that's done at these agencies that we all depend on. And so, if cuts happen, or further cuts happen, then we're jeopardizing this information that we all need to plan, to predict the weather of the future, to predict the climate of the future, and so, you know, it's a very concerning shift that I hope will actually not come to pass ultimately.

BELTRAN: Jennifer Francis is a senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center. Jennifer, as always, thank you for your time today.

FRANCIS: My pleasure. Happy to help anytime.

Links

Science | “Earth’s Clouds Are Shrinking, Boosting Global Warming”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth