April 11, 2025

Air Date: April 11, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Trump Attacks State Climate Laws

/ Aynsley O'Neill & Paloma BeltranView the page for this story

President Trump has issued an executive order titled “Protecting American Energy from State Overreach”. The order directs the U.S. attorney general to identify and block state laws that deal with climate change, environmental justice, and carbon emissions, including the climate superfund laws passed in New York and Vermont that impose stiff fines on big fossil fuel companies. Hosts Aynsley O’Neill and Paloma Beltran report. (02:22)

Eco-Rollbacks From Trump

View the page for this story

The Trump administration has paused funding from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, impacting multiple projects that were already approved and in progress. The Environmental Protection Agency also set up a new email address for companies to fast track requests for exemptions of pollution rules under the Clean Air Act. Former New England EPA administrator David Cash joined Host Aynsley O’Neill to discuss. (08:19)

Complex Air Pollution and Public Health

View the page for this story

Thousands of people across the United States live near multiple industrial facilities and petrochemical plants that expose them to higher levels of air pollution, but chemical exposure risk is commonly regulated one chemical at a time. A recent study conducted by a group of Johns Hopkins researchers found that “fence line” residents are at higher risk for multiple health problems because of the toxic mix of air they breathe. Lead author Dr. Keeve Nachman joined Host Paloma Beltran to walk through the study. (10:17)

Sneezing and Climate Change

View the page for this story

Warmer temperatures are causing plants to bloom earlier and longer, leading to longer and more intense pollen sneezing seasons for people susceptible to allergies. Dr. Neelu Tummala is an ear, nose, and throat physician at NYU Langone Health who has written on the impact of climate change on our allergies. She joined Host Aynsley O’Neill to talk about the connection between climate change and allergies. (09:57)

Listening on Earth

View the page for this story

At Living on Earth we encourage listeners to share glimpses of their world through audio recording. We feature a collage of different audio recordings from across the country. (01:47)

Shrinking Clouds

View the page for this story

In terms of physics, global warming comes down to an energy imbalance as Earth is taking in more energy than it is releasing. A new study suggests that shrinking cloud cover is playing a big role in that imbalance. Jennifer Francis, an atmospheric scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center joined Host Aynsley O’Neill to discuss. (14:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

250411 Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Beltran, Aynsley O’Neill

GUESTS: David Cash, Jennifer Francis, Keeve Nachman, Neelu Tummala

[THEME]

BELTRAN: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

BELTRAN: I’m Paloma Beltran

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

The Trump EPA is publishing a loophole that lets chemical companies off the hook from Clean Air Act regulations.

CASH: It's setting up an easy way for a company or now what we've seen an entire industry, the chemical industry, has submitted an email asking for relief from these kinds of regulations that will just put more toxic air pollutants in our air that we breathe.

BELTRAN: Also, Earth’s clouds are shrinking, giving a boost to global warming.

FRANCIS: That has been a climate controversy for quite a while, so this is another really concerning vicious cycle, one of many in the climate system that make the initial warming even more than it would be otherwise

BELTRAN: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out in The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Trump Attacks State Climate Laws

President Donald Trump is applauded by a group of coal miners at the April 8th event where he signed the executive order designed to block state action on climate change. (Photo: The White House, Flickr, U.S. Government work)

O’NEILL: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

It’s another day, and another executive order for the Trump Administration. On April 8th, the President ordered the U.S. attorney general to find and block state laws that deal with climate change, environmental justice, and carbon emissions, to name a few.

O’NEILL: The order, titled “Protecting American Energy from State Overreach” instructs the Department of Justice to stop the enforcement of state climate laws. It says that quote, “states have enacted or are in the process of enacting “burdensome and ideologically motivated ‘climate change’ or energy policies that threaten American energy dominance and our economic and national security.”

BELTRAN: Some of the laws that were explicitly mentioned are the climate superfund laws passed in Vermont and New York. These laws are aimed at holding the fossil fuel industry financially accountable for climate damages, but President Trump’s new executive order calls them extortionary. Meanwhile, California’s cap-and-trade system is said to be “punishing carbon use” by requiring businesses to purchase allowances for their carbon pollution.

O’NEILL: After the announcement, two Democratic governors, Kathy Hochul from New York and Michelle Lujan Grisham from New Mexico, pushed back, saying “The federal government cannot unilaterally strip states’ independent constitutional authority.” The two governors chair the U.S. Climate Alliance, a collection of 22 states and two US territories that are committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions in keeping with the 2015 Paris Agreement.

BELTRAN: On the contrary, the American Petroleum Institute issued a statement in support. It reads, in part “We welcome President Trump's action to hold states like New York and California accountable for pursuing unconstitutional efforts that illegally penalize U.S. oil and natural gas producers for delivering the energy American consumers rely on every day.” These federal actions follow President Trump's promises to promote the coal industry as well as expand oil extraction, all of which contribute to the burning of fossil fuels and climate change.

O’NEILL: The U.S. attorney general has to report on the actions taken against state climate laws and recommend other actions from the president or Congress within 60 days of the executive order. We’ll be covering this story in depth in the coming weeks, but for now, you can find out more at our website, LoE.org.

Related link:

Reuters | “Trump Issues Order to Block State Climate Change Policies”

[MUSIC: Vanderlei Pereira and Blindfold Test, “Les Matins de Rixensart (The Mornings of Rixensart)” on Vision for Rhythm, by Vanderlei Pereira, Jazzheads Records]

Eco-Rollbacks From Trump

Cash disagrees with the new EPA administrator, Lee Zeldin, who claims that the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund program is wasteful. (Photo:: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

O’NEILL: The Trump Administration has been making moves to slash funding and personnel at the Environmental Protection Agency. One such program affected accounts for $20 billion in Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund grants, pausing several Green Bank projects that were already under contract for the money. And recently the EPA has promoted the opportunity to seek exemptions from the Clean Air Act, which is music to the ears of fossil fuel and chemical companies alike. David Cash is the former US Environmental Protection Agency New England Administrator, and he joins us now to talk about recent actions by the EPA. David, welcome back to Living on Earth!

CASH: Thanks. It's great to be here.

O'NEILL: So, David, one of the latest pieces of news I've heard out of the EPA is about an email address they've set up where companies can request a special exemption from certain requirements under the Clean Air Act. What's going on there? What's this new system all about?

CASH: Yeah, this is just another in the growing list of assaults on our clean air and clean water and assaults that will cause more asthma, more heart attacks, more cancer, more birth defects. Essentially, it's saying this is a Get Out of jail free card in what's otherwise a very robust regulatory program that makes sure that industry doesn't pollute in a way that hurts our health. And basically, it's setting up an easy way for a company or now, what we've seen this past week, an entire industry, the chemical industry, has submitted an email asking for relief from these kinds of regulations that will just put more toxic air pollutants in our air that we breathe. Unprecedented. This has never been done like this before.

O'NEILL: And you mentioned that people have already started applying for these waivers. What is the sort of status of that? And how soon do you think we'll be seeing the impacts from it?

CASH: Yeah so, we know that one large power plant, a coal burning power plant, has already submitted a waiver. That happened shortly after the announcement was made, and just in the last couple of days, basically the entire chemical industry has also submitted such a waiver. The American Chemistry Council and the American fuel and petrochemical manufacturers associations have submitted this waiver to do a broad brush waiver from all of these emission standards that took years and years, huge amount of scientific effort, public input, input from industry themselves, to assure that the technologies that were required in these regulations are available, are economical, And that, of course, there's no impact on national security. Those are the two hooks in the Clean Air Act that this EPA is using, saying, if the technology is not available or it might impact national security, neither of which, neither of which there's any evidence of. We've seen this now time and again with administrator Zeldin is making these kinds of claims that have no basis in the evidence at all.

O'NEILL: Well, speaking of claims from EPA Administrator Zeldin, there's this greenhouse gas reduction fund that has been the subject of many such claims. Now you are on the steering committee of that greenhouse gas reduction fund. Can you explain what that was and what the status of that money is now?

David Cash is the former Administrator of EPA's New England Region under Region 1. (Photo: Courtesy of David Cash)

CASH: Yeah. So, the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund was created by Congress by statute, legally in the Inflation Reduction Act, and it was a really innovative. And exciting part of the act, because what it did was, instead of just giving out grants, for example, it was creating green banks, $20 billion that would go to eight lending institutions and networks of these lending institutions that have a very robust history of lending money to businesses and communities and cities and towns. And the whole idea was to unleash investments for energy efficiency, renewable energy, electric vehicles, all these things that would bring down energy costs, increase our energy independence, grow jobs and spark innovation and entrepreneurship. And what was really amazing about this is that the analysis was that for each federal dollar that was invested, $7 would come off the sidelines from the private sector. So, for that $20 billion about $150 billion the private sector would step in to make investments and administrator Zeldin raised these completely phony accusations of waste, fraud and abuse, so the funding has been frozen.

O'NEILL: What communities are going to be impacted if the money from that Green Bank never makes its way to the programs it was promised to?

CASH: So, there are a number of specific communities that already had applied and did the very rigorous application process to get the actual grants from the green banks, and basically, this is going to impact communities all over the country who are depending on this kind of funding to for example, there's one program in Arkansas to expand solar to bring down costs for energy for communities that's on hold. There's a plan that was worked on in collaboration with Oregon and New York to build public housing, very energy efficient public housing that would lower energy costs for those who live in the houses, which again, supposedly we're in the middle of a housing emergency, and we're in the middle supposedly of an energy emergency. This would have solved both of those problems for these communities. There's funding that was going to truckers that want to electrify so they can lower their costs for trucking and create cleaner air for the kids in the communities that they drive through. That's on hold. So, all of this based on no evidence at all, is freezing funding that would have lowered asthma rates for kids, that would create great jobs, that would create greater energy independence. So, we're seeing missed opportunities in communities all over the country, rural, urban, everywhere.

O'NEILL: And David, I understand that there are lawsuits pushing back against this.

CASH: Yes, the Green Banks, that had competed for and qualified for this funding and is now frozen by the EPA, has brought suit against the EPA in the US District Court in District of Columbia in DC, and in fact, most recently, a judge who's been looking at this basically said that EPA quote “proffered no evidence to support their basis for the sudden terminations.” So that's where things stand right now. But let me kind of take a step back. We've talked about these waivers, and we've talked about the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, and we could look across the actions of this administration, not just in environment, but in health and human services, and national security, that the actions that are being taken is an example of which in the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund are unlawful, extra lawful abuses of executive power that step well beyond general differences in policy, but go toward a constitutional crisis. We're in that right now. We are in a constitutional crisis right now where the rule of law is being questioned in a fundamental way. And I happen to be in the environment field, and I'm seeing it here, but I talk with colleagues in many other sectors, and we're seeing this all over.

O'NEILL: David Cash is the former US Environmental Protection Agency, Administrator for New England. Thank you for joining us, David, and we will talk to you soon.

CASH: Sounds great. Thanks so much.

O’NEILL: We reached out to the Environmental Protection Agency, who pointed us to a section in the Clean Air Act which states that the President may provide exemptions when he determines that, quote, “the technology to implement such standard is not available and that it is in the national security interests of the United States to do so.” They also confirmed the window for Clean Air Act exemption requests closed on March 31st, 2025.

Related links:

- Read more about the Clean Air Act exemption application

- Learn more about David Cash’s resignation from the EPA

- Learn more about the lawsuit against the EPA from one of the plaintiffs, Climate United

[MUSIC: Hauser with Yiruma, “Kiss the Rain” on Classic II, by Billie Myers, on Masterworks, a label of Sony Music]

BELTRAN: Coming up, climate change is making pollen season worse. For tips on how to handle it. Stick around!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Vanderlei Pereira and Blindfold Test, “Les Matins de Rixensart (The Mornings of Rixensart)” on Vision for Rhythm, by Vanderlei Pereira, Jazzheads Records]

Complex Air Pollution and Public Health

A Chester, Pennsylvania neighborhood sits adjacent to the ReWorld Delaware Valley facility, formerly known as the Covanta facility, during the time of the study. The Delaware Valley Resource Recovery facility (DVRRF) is a permitted waste-to-energy facility. The study showed that fence line communities are at a higher risk from air pollution than previously understood. (Photo: Peter DeCarlo)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Scores of Americans live near petrochemical plants and other industrial facilities that constantly release chemicals into the environment. Historically, the risk of chemical exposure to those residents has been examined one chemical at a time. But according to a group of Johns Hopkins University researchers, that approach fails to accurately ascertain the overall air pollution and health risks to people who live near those industrial sites. So, using what’s called a mobile laboratory, or a lab on wheels, that team of researchers drove around petrochemical facilities in Chester County Pennsylvania for about a month measuring chemicals in the air at all hours of the day and night. Their recently published study found that fence line residents are at higher risk for harmful air pollution because of the toxic mix of air they breathe. And the research was recently submitted into the record as part of a Pennsylvania bill that requires the state permitting process to look at cumulative impacts. Dr. Keeve Nachman is the Robert S. Lawrence Professor of Environmental Health and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University. He led the study and joins us now to explain more. Dr. Nachman, Welcome to Living on Earth!

NACHMAN: Thanks so much for having me, Paloma.

BELTRAN: So, your team is using a new approach to measure air pollutant risk across fence line communities. What method did you use? How did that look like?

NACHMAN: So, we have two exciting methods that I think make the work that we're doing so important. The first is that we are using cutting edge mobile measurement technology. So, we essentially have a chemistry lab in a van or a small truck, and we're able to drive that truck around communities where we're trying to understand the impact of air pollution and measure toxic chemicals in real time and over space. And it allows us to develop these highly confident estimates of air pollutant concentrations that we then translate into some estimate of how likely people are to get sick if they were to breathe air like this over their lifetimes. So that's the first interesting piece, is that we have really great air measurement data, and then the other piece of what we've done that's so neat is we've taken this new approach to trying to translate information about what people breathe into some sort of characterization of how likely they are to get sick, if what we measured reflects what they breathe over a lifetime.

The Aerodyne Mobile Laboratory that the Johns Hopkins University team used to conduct research in Chester and other southeastern Pennsylvania towns. (Photo: Peter DeCarlo)

BELTRAN: How does your research compare to the traditional approach of measuring chemicals?

NACHMAN: So, our research changes the way we interpret information about concentrations of chemicals that people are exposed to. We developed a novel approach to characterizing the impact of chemicals that is more holistic than the traditional regulatory approach to interpreting information about people's exposures when they breathe polluted air. And what's really important about our approach is that our approach recognizes that each of the chemicals in the mixture can target multiple parts of the body, and it doesn't ignore the less sensitive parts of the body that each chemical affects. And so, when we take all that information together, we may find evidence of risks that the traditional methods may miss. And so, in particular, when you use the traditional regulatory risk assessment approach with the air pollution data that we developed in Pennsylvania, you actually don't find that any of the organ systems in the body would be at an elevated risk. And so, as a result of that, you may conclude that the air pollution exposures that people in that community incur are not a problem, and if you believe that they aren't a problem, there's very little motivation to do anything to change people's situations, right?

So, our method, because it does more than just account for one effect per chemical. It accounts for the fact that each chemical could elicit multiple effects in the body, we come to different conclusions. So, we actually find for five different parts of the body an elevated risk that people breathing that air may experience five different non cancer health outcomes, including respiratory effects and two others, and those effects would be entirely missed using the traditional regulatory approach. And the reason why that's so important is that the interpretation of our results would likely lead to very different approaches to managing risks in the community, we find that, given current conditions, it's reasonable to expect that people would get sick with one of those five diseases or ailments or affected organ systems. And as a result, if posed the question of whether it would be okay to permit an additional industrial facility in the region, I would think we would likely determine, no the community is already overburdened, given what we're able to estimate now and again, that's different from what you might conclude given a traditional risk assessment, where we might say “there's no reason to think that the conditions that people are currently experiencing are problematic. So go ahead.”

The team tested the air around industrial plants such as the Evonik facility in Chester, with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection measurement site in the lower right of the photo. According to the EPA's Toxic Release Inventory, the Evonik facility's production includes ammonia, sulphuric acid, sodium hydroxide and sodium sulphate. (Photo: Peter DeCarlo)

BELTRAN: How can this approach be applied to other fence line communities across the United States?

NACHMAN: The method we developed for this study has implications far beyond the community in southern Delaware County and Pennsylvania. I'm thrilled that we were able to use it to help characterize the risks that they may be facing. That's really, really important and a big part of our collaboration with them, but this approach can be applied anywhere. So certainly, it has value in other communities living on the fence line. Cancer Alley in Louisiana is certainly a place where there's heavy petrochemical and other industrial processing that may be impacting the lives and the health of people who live in those communities, and I think it would be readily deployable there our method, but I think this method really even beyond fence line communities and even beyond air pollution, has relevance. There is nowhere in our country or anywhere in the world where people are exposed to a single chemical at a time, and our long-standing approach of trying to regulate them on a one-by-one basis is missing the boat and under protecting people.

Scientists from Aerodyne Research and Johns Hopkins University drove the mobile laboratory all hours of the day and night to measure the pollution experienced by residents who live near industrial facilities in Delaware County, Pennsylvania. From left to right: Ellis Robinson (JHU), Peter DeCarlo (JHU), Conner Daube (AR), Ben Werden(AR), Joseph R. Rosciolli (AR), Kenji Lizardo (AR), Megan Claflin (AR), Roger Sheu and Mina Tehrani (JHU). (Photo: Peter DeCarlo)

And so we are excited to use this method elsewhere, to use nuance and a fuller understanding of the negative action of each chemicals to characterize the risks that people face, and in the immediate future, we're looking at taking this method and using it, not only for air, but looking at a community where we can get data on air, on drinking water, on soil exposures, on consumer products, on food, and taking those exposures together and saying something about what that collective experience means for health. And really, that's the truest essence, or that's a major step towards this idea of cumulative risk assessment. Looking at mixtures is just one piece of it. You know, mixtures are very important, but we also recognize that chemicals are not the only stressor people experience in their lives, and we often know that fence line communities are experiencing other forms of disadvantage that may make them more vulnerable to chemical exposures. So, if we aren't accounting for all of those other stressors, and we're making decisions in the absence of that consideration, we aren't protecting people the way we should and the way they deserve.

BELTRAN: You know, Keeve, your study was published at a time when the Trump administration is cutting and limiting environmental justice programs across the country. What impact could this research have on policy making, especially regarding rules to protect our most vulnerable populations? What are you hoping to see here?

NACHMAN: I have to acknowledge that this is a time when many of us are feeling discouraged about work like this being used in the immediate future to intervene on injustices faced by fence line communities around the country. That said, this work and the approaches here and a lot of the work that many of my colleagues are doing in the field, hold a lot of promise and represent important advances towards true characterization of the combined or cumulative burdens that communities are facing. And I think now is a time to develop these methods and to really hunker down and generate the evidence we need to use as a basis for smarter policy making when windows open up in the future where there is receptivity to making better decisions. I'm confident that those windows will reopen, even if, in the short term, we feel like they're closed. So, I haven't lost hope, and we're moving ahead with our research and with deploying these methods, because we know the time will come where there will be receptivity to using them, and change will happen, and we will do a better job of protecting the health of the public.

Keeve Nachman, Robert S. Lawrence Professor of Environmental Health and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University, analyzed the data from the testing conducted by his colleague Peter DeCarlo and the team of Johns Hopkins University and Aerodyne Research scientists. (Photo: Courtesy of Keeve Nachman)

BELTRAN: What lessons do you hope residents of other fence line communities learn from this study?

NACHMAN: The only thing I really hope that residents of fence line communities take away from this is that we're working hard to develop the data that we can use to protect them. I want to be really clear, and I'm asked this by reporters a lot, what can residents do differently? I don't think the burden should be on residents to do anything differently. I think residents are the ones who are bearing the brunt of the decisions of other actors like the industry and federal, state and local governments. They're the ones that should be doing things differently to protect residents. Residents should feel free to live their lives as they want. And so, I bristle a little bit at the notion that there's anything anyone can do other than know that we are not losing sight of the prize of public health protections for all U.S. citizens and beyond.

BELTRAN: Keeve Nachman is the Robert S Lawrence Professor of Environmental Health and engineering and Associate Director of the Center for a Livable Future at Johns Hopkins University, thank you for joining us.

NACHMAN: Thanks so much for having me.

Related links:

- Read this study in Environmental Health Perspectives

- Washington Post | “Breathing Dirty Air Is Worse for Your Health Than We Thought”

- Franklin County Press | “Pennsylvania Bill Aims to Address Cumulative Environmental Impact in Permitting Process”

[MUSIC: Jamie Laval & Ashley Broder, “Staircase” on Zephyr in the Confetti Factory, by Ashley Broder, self-published]

Sneezing and Climate Change

In Brisbane’s Botanic Gardens, a tiny native bee works its way through a flower, harvesting pollen. (Photo:Weldon Thompson, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

O’NEILL: We are in the middle of sniffling season. In the southeast, the yellow mist of pollen might have peaked already. But for the millions of allergy sufferers in the colder parts of the country, the season of misery will be around for a while. And scientists believe that our warming climate is intensifying seasonal allergies. With warmer weather, plants are blooming earlier, and an increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels prods plants to step up pollen production. Altogether, it means that allergy season arrives earlier, ends later, and boasts more pollen throughout. To learn more about the connection between climate change and our itchy eyes and runny noses we are joined by Dr. Neelu Tummala. She is an Ear Nose and Throat physician at NYU Langone Health who has written extensively on the impact of climate change on our allergies. Dr. Tummala, welcome to Living on Earth!

TUMMALA: Thank you. It's great to be here.

O’NEILL: Let's take this year's allergy season and compare it to one from, say, 20 years ago or 50 years ago. What's the difference between allergy seasons now and the allergy seasons of the past?

TUMMALA: The allergy season has changed, and a big reason for that change is that the environment that we are living in on a day-to-day basis, is different now than it was 50 years ago. Because of global warming, temperatures have risen as compared to preindustrial times, and so with those changes in temperatures, there's also been some changes in precipitation patterns, and these environmental changes have affected the pollen allergy season specifically. So, what the data shows is that the pollen allergy season on average in the United States is about three weeks longer now than it was 50 years ago, and so this accounts for both an earlier start to the pollen allergy season. So usually, tree pollen is an issue in the spring, and then in the fall, the pollen is lasting longer, so that's usually ragweed pollen. And the reason for that is when we have warmer temperatures, the ground thaws earlier in the year, so this allows the trees to grow earlier, and then the ground doesn't freeze as quickly in the fall, and so the pollen lasts longer. Another difference we're seeing now, as compared to 50 years ago, is that there's a lot more pollen in the air. So, the data shows that there's about 20% more pollen in the atmosphere in the United States than there was 50 years ago. And this, again, is related to some of the impacts that we're seeing from global warming and increased carbon dioxide, one of the main greenhouse gasses that is warming the planet, and how that impacts the ways that trees and plants grow.

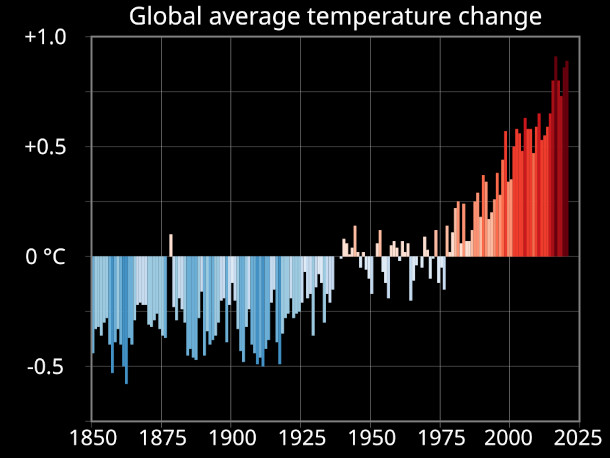

In the last two decades, data has shown continuous spikes in the global average temperature. This has altered the growing season for many pollen-producing plants. (Photo: Sebastian Wallroth, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

O’NEILL: And so, this is happening in both the spring pollen seasons and the fall pollen seasons, and they're both stretching out longer like this. What's the implication for, you know, public health when it comes to having a longer allergy season?

TUMMALA: So, there's a couple of different things that I am really concerned about as a physician who's treating patients who are presenting to me with pollen allergy symptoms. So, the first is, how is this impacting quality of life? So, for anyone who has pollen allergies, it's not fun, and about 20% of Americans have pollen allergies, so this increases the amount of symptoms that patients have to deal with. So, this includes the nasal congestion, the sneezing, the itchy, watery eyes, the runny nose, all of those symptoms are going to be starting earlier and lasting longer. So basically, it's just having to deal with these symptoms that impact our quality of life, impact our sleep efficacy, impact our ability to pay attention during the day for longer throughout the year. The second issue is, when there's more pollen in the air, the symptoms themselves are likely to be more significant, right? So, if you're dealing with more pollen, then that's going to be more of an issue in terms of how much it's irritating and causing inflammation inside the nose and causing worsening symptoms than you used to have. So, in order to control these symptoms, a lot of times, people have to adjust their allergy medications, and so this may include starting your allergy medications earlier in the year and using them longer in the fall, or potentially even increasing the amount of allergy medications that you're using. So, these are going to have a direct impact on your wallet, right? If you're using more medication. You have to pay more for medication to be able to control your symptoms, and so there is definitely concern for the economic impact this is having on anyone with pollen allergies.

O’NEILL: And I mean, I've had seasonal allergies my whole life, but that doesn't actually mean they know that much about them. To what extent are seasonal allergies just some sort of unfortunate annual discomfort, versus something that could be more serious?

Not only does air pollution from fossil fuel burning contribute to asthma and upper respiratory disease, but the global warming that results from carbon emissions can exacerbate environmental allergies, also leading to asthma and upper respiratory complications. (Photo:Janak Bhatta, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

TUMMALA: For some people, pollen allergies are more of a bothersome thing, right? They might have very mild pollen allergies, so they'll feel a little bit of sneezing congestion. It's something they notice, but it may not have a significant impact on their day to day versus there are some people where allergies are much more severe, they have a much stronger reaction to it. And for some people, allergies can trigger asthma attacks. That's called allergenic asthma. And so, it's not just dealing with the nasal symptoms, the itchy, watery eyes, but it can also impact your breathing. And so those are some of the really concerning sequelae of pollen allergies. Is how is it impacting your breathing? How is it impacting upper airway inflammatory diseases, other airway diseases and breathing complications associated with that.

O’NEILL: Beyond your typical over the counter or even prescription allergy medication, what are some tips you would give to pollen sufferers when they're going through these seasonal allergies?

TUMMALA: So, there's a couple of different things that can be helpful when you're thinking about avoiding the impacts of pollen allergies. So, one of the first things is, how do you protect yourself from pollen exposure? And so, one way is to check the pollen levels, and on days where the pollen levels are really high, try to minimize the amount of outdoor exposure that you have, you can also wear a mask when outdoors, because that will definitely help mitigate the amount of pollen that you're exposed to. We also know that right now, we're going through tree pollen. The highest levels tend to be in the morning and the afternoon, so maybe choosing to be outdoors more in the late afternoon or evening, you'll probably be exposed to lower pollen levels. When you come back home from being outdoors, it's really helpful to change your clothes, shower if you're out with your pet, sometimes giving your pet about making sure you get all the pollen out of the fur can be helpful. Keeping your windows closed when you're driving your car, when you're at home, will definitely help prevent pollen from getting in the home. So those are some tactics, just to avoid the pollen exposure itself.

The next level is okay, if you are exposed to these pollen levels, then how do we protect ourselves from them? And that's where, like you said, the allergy medications come into play. And there are both nasal sprays and eye drops and oral allergy medications that you can take. And these definitely deserve a really good discussion with your allergist or ENT physician to talk about what's going to be an ideal regimen for you to control your symptoms. And then the third area that we think about is if these interventions aren't enough, or, you know, if someone just really wants to see what else can be done, that's when allergy immunotherapy can be helpful. And so again, this is a conversation you'd have with your allergist or ENT physician to say, you know, could allergy shots be helpful for me when I'm dealing with my pollen allergy symptoms.

O’NEILL: Beyond a seasonal allergy, you know, these pollen allergies we've been talking about, how is climate change affecting life for allergy sufferers generally?

TUMMALA: So, another way that global warming is impacting anyone who has environmental allergens is its impact on extreme weather events like flooding and hurricanes. So, with global warming, climate scientists have showed that extreme weather events like flooding and hurricanes are definitely more intense, and the frequency of some of these extreme weather events has increased. And so, one of the big concerns is the water that's left after these events, and the increased risk of mold growth and mold exposure. Mold is a really common environmental allergen as well, so anyone who's been in a home that has been flooded or has had to deal with standing water, the mold exposure is definitely something that we also want to be conscientious of, and definitely make sure that we address that both from cleaning the mold standpoint, but also from protecting ourselves from the allergy symptoms associated with it.

Dr. Neelu Tummala is an Ear Nose and Throat physician and assistant professor of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery at NYU Langone Health. (Photo: Neelu Tummala)

O’NEILL: And Dr. Tummala, what do you see as the importance of addressing our changing climate from a healthcare perspective?

TUMMALA: So, addressing our changes in climate is incredibly important from a healthcare perspective. Climate change itself has had a huge impact on public health, both here in the United States and globally, and it is one of those public health concerns that's going to continue to get worse unless we do something about it. And so, you know what we talked a lot about today is, how do patients protect themselves? And so, it is about avoiding the exposure and changing your medications, you know, avoiding being outdoors at certain times. All of that you know, is really important. But what we also need to do is make the environment that we live in a healthy environment. We can't expect to be as healthy as we want to be if we live in an environment that is not healthy. And so, one of the major things that we really need to do is we need to transition off of fossil fuels that are contributing to emissions that are warming the environment. They're contributing to global warming. We need to improve air quality. We need to, you know, make sure that the water that everyone is drinking is clean. And so, all of these things are really essential to making sure that the environment that we're living in is healthy, so that we can all be healthy. And so, at the root of all of this is really addressing the root cause of these health concerns, and that's climate change. And so that's why climate action is so important for improving public health.

O’NEILL: Dr. Neelu Tummala is an ENT physician at NYU Langone Health. Dr. Tummala, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

TUMMALA: Thank you so much for having me. It was really great to talk about such an important topic, and I appreciate you all covering this.

Related links:

- Learn more about climate change’s impact on allergies

- Dr. Tummala’s article on severe allergies and climate change

[MUSIC: Polemil Bazar, “Les Visceres” on Putumayo Presents Quebec, by Hugo Fleury, Putumayo World Music]

Listening on Earth

A spring peeper perched on a tree. (Photo: U.S. Geological Survey, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

O’NEILL: In past broadcasts we’ve encouraged listeners to send us some audio postcards. We’re about to listen to a collage of sounds recorded by fellow earthlings.

You may want to turn the volume up or put on headphones for this.

MATTHEWS: Hello, my name is Chivas Matthews, a retired Navy veteran, and an operations and environmental management major at the University of Arizona's global campus. I’m located in Gulfport, Mississippi. I’m an avid bird watcher. And these are the sounds of my backyard.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

GOULET: My name is Martin Goulet. I’m on the Central Mass Rail Trail in New Braintree.

[RIVER SOUNDS]

O’NEILL: And this final sound is a chorus of spring peepers surrounding a pond in Norwell, Massachusetts, courtesy of Karen Fortier.

[PEEPER AUDIO]

O’NEILL: If you're interested in sharing a listen into your surroundings with Living on Earth, you can use any smartphone device to capture the sound. Think about what draws your attention when you’re out in the world, whether that’s the middle of a forest or your daily commute. You can use any sound recording app like Voice Memos or Voice Recorder. For the best audio quality make sure to stand still for at least two minutes without talking or fidgeting. But we do want to hear from you! So be sure to let us know where you are, what you’re hearing and what inspired you to record the sound.

Then you can email us the file at comments at loe dot org, and we might just use your audio postcard on the air! That’s comments at loe dot org.

Related links:

- How to make a sound recording on an iPhone

- How to make a sound recording on an Android

[MUSIC: Tommy Emmanuel, “Song for A Rainy Morning” on The Best of Tommysongs, CGP SOUNDS]

BELTRAN: Just ahead, our planet’s cloud cover has been declining for years, and the science spells bad news for our warming climate. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Tommy Emmanuel, “Song for A Rainy Morning” on The Best of Tommysongs, CGP SOUNDS]

Shrinking Clouds

Cloud cover has been shrinking over the last 20 years, according to an analysis of NASA satellite data. (Photo: NASA Johnson, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

When we talk about global warming, the evidence is overwhelming. Simply put, more energy enters the planet than leaves it, and the majority of this imbalance is tied to our greenhouse gas emissions. Much of the rest can be tied to shrinking ice coverage, which exposes darker ground that absorbs more heat. And paradoxically, cleaning up our polluted air does the same, since the toxic haze of airborne fine particles and aerosols reflects light and stops it from hitting the earth’s surface. But altogether, there has still been an unexplained gap in earth’s energy budget. So, NASA scientists now believe that they’ve found the missing piece. Using satellite data, they calculated a reduction of reflective cloud cover by at least 1.5% in the last 2 decades. That might seem like a small amount, but it adds up quick. And this time, it’s not fed by the pollution paradox. 80% of the reflectivity changes were caused by shrinking clouds, instead of the darker, less-polluted hazes. Jennifer Francis is an atmospheric scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, and she joins us now to explain this recent study.

FRANCIS: Clouds are beautiful in one sense. I mean, we love looking up and… And seeing patterns in them. We love what they do to our sunrises and sunsets. We depend on them for rainfall and snow. And yet, there's this other side of them that they have a really important role in the Earth's climate, and they're one of the hardest things to figure out in terms of how the climate has changed and will change, and that is because they have this dual role of reflecting heat from the sun but also trapping heat down by the earth surface. And so for us climate scientists to try to figure out how they're going to change in the future, what their role is going to be in terms of either making global warming worse or perhaps offsetting it somewhat, it's probably the biggest source of questions that still exist in our ability to look forward and try to figure out how the climate system is going to change.

Clouds function differently in various parts of the planet. For example, clouds covering stretches of bright white ice would absorb and release heat differently than clouds covering swaths of dark blue ocean. (Photo: Jeremy Stewardson, Unsplash, Unsplash License)

BELTRAN: So, Jennifer, what did this study find?

FRANCIS: So, the main finding is sort of clearing up something no pun intended, that has been a climate controversy for quite a while, and that is whether changes in clouds are causing warming to become warmer, or whether they're reducing the warming. And what this study basically found is that indeed the changes in cloud cover are causing the warming to be even stronger. So, this is another really concerning vicious cycle, one of many in the climate system that make the initial warming even more than it would be otherwise.

BELTRAN: And how was this study conducted? You know, what tools did researchers use to come to that conclusion?

FRANCIS: Yeah, so the main tool that was used was measuring clouds from satellites. And satellites can measure various wavelengths of energy. You could think of it as different wavelengths of light, but some of that light we can see, and some of it we can't, and clouds affect these different wavelengths differently. And of course, there's many different kinds of clouds, which makes it so complicated, because some clouds are made of water droplets. Some are made out of ice particles. Some of them are high up in the atmosphere. Some are low. And so, sorting out all the ways that clouds are changing and how they're affecting the heat that's absorbed or released by the Earth is not straightforward. So, the first things you have to do in a study like this is try to measure these different kinds of clouds, make sure you know what you're seeing from outer space, and then being able to detect how they might be changing over time. And I can tell you from my own work that it is not easy, because it depends on many things. These changes in clouds, it depends on what's underneath them, whether it's ocean or land or snow or ice, and all of those things really complicate these measurements, but having many different wavelengths of light that you can measure helps you sort out some of these differences, and that's what these researchers have been able to do. And what they were looking for was mostly changes in the coverage of these different types of clouds and using these satellite measurements of different kinds of light, that's what they were able to do.

A layer of fog blankets Mill Valley, California. Jennifer Francis notes that clouds off the coast of California tend to spread out in a uniform manner, appearing very bright and white to a satellite. (Photo: Zetong Li, Unsplash, Unsplash License)

BELTRAN: And how big are these changes to both the size of the clouds and the movement of the clouds?

FRANCIS: Well, they're not very big really. They're on the order of a couple percent. 2% doesn't sound like much, just like warming of the earth by 1.5 degrees doesn't sound like much, but it's having a big effect. So, one other important piece of information is that clouds do two things. They reflect sunshine, so that's a cooling effect. If there are more clouds, then they reflect more of the sun's energy back to outer space. But clouds also act like a blanket, so they also trap heat, just like greenhouse gasses do, and so there are these competing effects that clouds have. So that was the other part of this study that makes it so complicated is you have to figure out whether any change in clouds you're seeing is having a net cooling effect or a net warming effect, and where those clouds are located and how high they are in the atmosphere and what they're made out of, affects that distinction.

BELTRAN: Well, not all clouds are created equal, right? So how much are complicating factors like cloud type or color making an impact here?

FRANCIS: Yes, so cloud type has a huge impact. The clouds that are made out of water droplets versus ice particles have a much stronger influence on the energy that is either trapped or absorbed at the surface. So, let's talk about a couple different cloud types. One is the sort of very layered clouds that we see in various parts of the ocean. You could think of off of the California coast, where the clouds tend to be very uniform and spread out in a layer. And if you looked down from a satellite, they would look like a very bright white object. So they are very good at reflecting sunlight back to outer space, and when they're missing, if that amount of cloud of that type is much smaller, then it's going to let a lot more of the sun's energy into the ocean, and that ocean underneath is very dark, so it absorbs almost every bit of that energy that the clouds either let through, or if they're missing, that hits the ocean surface. If that same kind of cloud was sitting over a snow field, say, it's a totally different story, because that surface underneath is already very white, and so it's really hard to see those clouds actually from a satellite, because the cloud is white, the snow is white, and it's really hard to tell the difference. So, when it comes to heating, it also doesn't make as big of a difference, because if you lose those clouds over snow, you're still going to reflect most of that energy right back to outer space. So not only does it matter what kind of cloud it is, but it also matters what that cloud is over.

BELTRAN: And what could explain the drop in cloud cover just far as we know?

Extreme heat and weather events are worsening, and the ongoing reduction in cloud coverage is only feeding into that pattern. (Photo: Athena Sandrini, Pexels, Pexels license)

FRANCIS: Well, there's many things that can affect the amount of cloud that's there. So, one would be just to have a smaller area of cloud because of how the winds are moving those clouds. Some clouds are formed by two wind currents meeting and then having that wind have to go up. And so, you can think of the belt around the equator that we call the inter tropical convergence zone. It's where the two trade wind systems meet and where they collide. So, these winds come together. It means that the air can't go down, because the Earth is there, so it has to go up. And when air goes up, it eventually will cool off enough so that the water vapor in that air will condense into a cloud. So, if those wind currents that cause those clouds to form changes somehow, it could cause that area of those very turbulent, convective, puffy clouds that you see in the tropics often, that belt could get smaller, or it could get wider. And so, this study has suggested that that particular belt around the equator is, in fact, getting narrower, and so those very bright white clouds that happen in the tropics, especially over the dark ocean, if those get smaller, then they're going to reflect less of the sun's energy, and more of that heat will go into the ocean.

So, wind currents is one thing that can happen, but it can also be changes in the temperature structure of the atmosphere. So, it's how temperature changes as you go up into the atmosphere. Generally speaking, it gets colder as you go up. And if you've ever flown in an airplane that isn't pressurized, you'll know that it gets colder as you get up there, but the rate of that change of temperature can also change. And so that point where water vapor, which is the gaseous form of water that's in the air all around us all the time, at some temperature, that water vapor will start to condense into little droplets, which is what we see as clouds. And so, anything that affects that temperature distribution in the atmosphere going up is also going to determine whether the clouds form sooner or form later as air goes upward. And that air could be pushed upward by a storm system, or it could be pushed upward by mountains. So, there's a lot of different ways that air is pushed upward to create clouds.

Jennifer Francis is a Senior Scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center. (Photo: Courtesy of Jennifer Francis)

BELTRAN: So according to this paper, global cloud circulation patterns are changing. What impacts can we expect to see in the next five or the next 10 years?

FRANCIS: Well, unfortunately, it means that the warming that we've already been observing in the last couple years were the warmest on record for the earth, probably going back 120,000 years, which is very disturbing all by itself. But this just means it's going to be even harder to turn this around or to slow the warming, which is exactly what we have to do, because we've already seen the cascading effects of what this warming is doing. We're seeing increased heat waves, which is the most direct connection between a warming globe and extreme weather events. We've seen longer lasting, more intense droughts, wildland fires and urban fires, and we've seen those in spades the last few years. And we're also seeing increased flooding events and heavy precipitation events that can lead to flooding, and that is because that warming air absorbs more water vapor, so when a storm does come along, it has more water to work with. I mean, all of these extreme events that have been happening more frequently, we're going to see that become even worse as the globe continues to warm, and part of that story is the reduction in these very bright, white clouds.

BELTRAN: We're chatting now at a time where a lot of national science agencies like NASA and NOAA are facing personnel and budgetary cuts from the Trump White House. How are you feeling about the future of scientific research in light of these cuts?

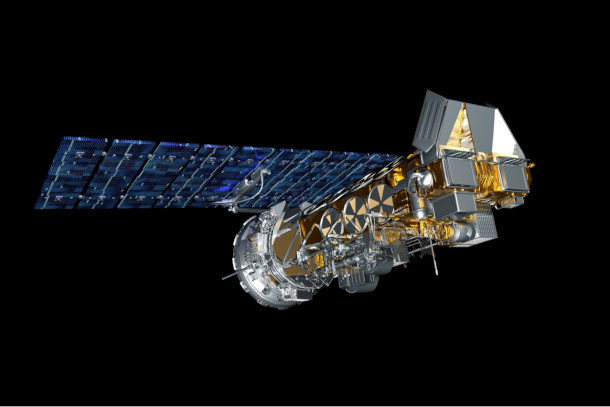

Shown here is a computer rendering of a TIROS N satellite, likely NOAA-18. Satellites operated by government agencies like NASA and NOAA provide crucial data for meteorologists, climatologists, and other researchers. (Photo: NOAA NESDIS Environmental Visualization Laboratory, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

FRANCIS: Yes, well, the cuts have been threatened. I mean, people have been let go. The cuts to funding have not really materialized quite yet. There's certainly a concern, because all of the good work that the National Weather Service, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, that's NOAA, NASA, I mean, the satellite observations that were used in this study to understand these changes in clouds came initially from satellites that were developed by NASA, and once that technology is proven, then usually NOAA takes over the maintenance of those satellites and the data that they collect, and then the scientists that work at NOAA and the National Weather Service in NASA figure out how to interpret those satellite observations and turn them into information that really matters to all of us, things like, how much worse is the climate crisis going to get? Where are these storms happening? All of that is the kind of work that's done at these agencies that we all depend on. And so, if cuts happen, or further cuts happen, then we're jeopardizing this information that we all need to plan, to predict the weather of the future, to predict the climate of the future, and so, you know, it's a very concerning shift that I hope will actually not come to pass ultimately.

BELTRAN: Jennifer Francis is a senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center. Jennifer, as always, thank you for your time today.

FRANCIS: My pleasure. Happy to help anytime.

Related link:

Science | “Earth’s Clouds Are Shrinking, Boosting Global Warming”

[MUSIC: Jenny Owen Youngs, John Mark Nelson, “sunrise mtn” single, OFFAIR Records]

O’NEILL: Next time on Living on Earth, we’ll meet Dr. Michael Long, a neuroscientist whose research shows how studying parrots might be the key to unlocking how the human brain allows us to speak. In his most recent paper, his team looked at the firings of individual neurons in birds’ brains and mapped them to specific vocalizations. He hopes that future research will shed light on not only how we speak, but how we decide what to say. It turns out that “bird brained” might not be an insult after all! That’s next week, on Living on Earth!

[MUSIC: Jenny Owen Youngs, John Mark Nelson, “sunrise mtn” single, OFFAIR Records]

O’NEILL: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Kayla Bradley, Jenni Doering, Daniela Faria, Mehek Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti McLean, Nana Mohammed, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

BELTRAN: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and You Tube music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. We always welcome your feedback at comments at loe.org.

Steve Curwood is our executive producer. I’m Paloma Beltran.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth