Pumping the Earth Dry

Air Date: Week of June 13, 2025

When people think of the plight of the Colorado River, they may think of the water on the surface, but Dr. Jay Famiglietti’s recent study showed that the river’s groundwater is also depleting quickly. (Photo: Doc Searls from Santa Barbara, USA, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

A recent study finds the Colorado River Basin has lost a tremendous amount of water in the last two decades, in part from thirsty farms pumping water from deep aquifers much faster than it can be replenished. Lead author Jay Famiglietti, a Global Futures Professor at Arizona State University, spoke with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran about the “Wild West” of unregulated groundwater, potential solutions and why the rapid depletion of ancient groundwater threatens the water supply for future generations.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

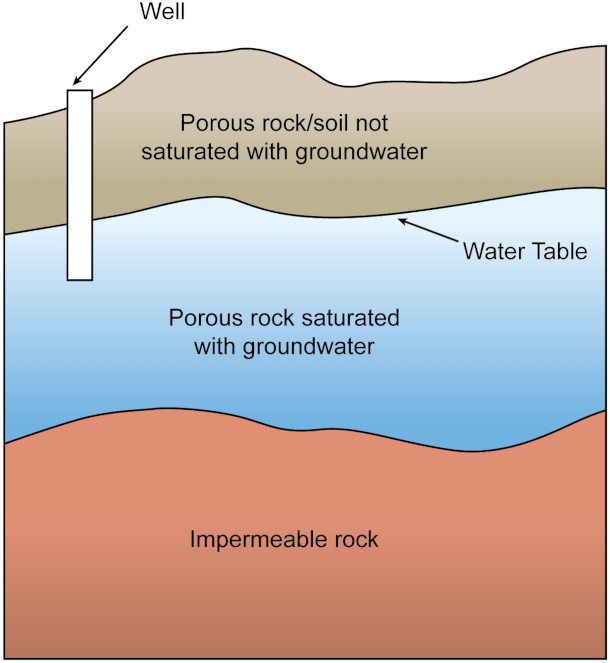

Even in deserts there are often large reserves of groundwater buried deep underground in aquifers that can take as many as thousands of years to fill. But our thirsty society is quickly burning through much of this ancient resource. A recent study published in Geophysical Research Letters found that the groundwater of the Colorado River Basin is being sucked dry largely by farms. And once those aquifers are drained, they’re not coming back any time soon. Parts of Mexico and seven U.S. states depend on the Colorado River Basin for their water. But it’s kind of a “Wild West” when it comes to groundwater in the West, since farmers and landowners have little incentive to conserve groundwater that’s mostly unregulated. Lead author of the study Jay Famiglietti is a Global Futures Professor at Arizona State University’s School of Sustainability and the former host of the podcast What About Water? He spoke with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

BELTRAN: You conducted a study showing that the Colorado River's groundwater is depleting. Talk to me about that study. And what are the big takeaways?

FAMIGLIETTI: We used over 20 years of satellite data from a satellite mission that we call GRACE. It's a NASA mission, and GRACE stands for Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment. And that particular mission is very good at helping us track changes in water availability and total water storage, all of the snow, the surface water, soil, moisture and groundwater. And it showed us that the Colorado River Basin has lost a tremendous amount of water over the last 22 years, as much as about 80% of Lake Powell and Lake Mead combined, and a lot of that was groundwater, something like 27 million acre feet, which is about the size of Lake Mead at capacity.

BELTRAN: You said 80%? That's a huge amount.

FAMIGLIETTI: It's an incredible amount of water. So I think the thing about groundwater is that it's out of sight and out of mind. And you know, there are a lot of people that are willing to take advantage of that and exploit that.

BELTRAN: And you know, part of your study discusses groundwater management and how it's effective in some places but not in others. How is groundwater management different from general water management?

Much of the Colorado River’s water is being used to grow alfalfa, a plant that becomes feed for livestock. (Photo: Philmarin, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

FAMIGLIETTI: Well, one of the big things is that it's really lagged behind for this reason that I just sort of alluded to, which is sort of out of sight, out of mind. So, you know, historically, most places have really focused on the water that they can see, which is the water in the rivers and lakes, and so that's been well managed, and the property rights have been worked out through the centuries, really. Groundwater is much later to the party, in the sense that it's taken a long time for groundwater management to happen in every state. I think California was the last, and that started in 2014. But even where we have groundwater management, the degree to which it's enforced or useful, really varies a lot over the United States. And I think a great example is Arizona, and only 18% of the state is covered by groundwater management. If you own property, you can drill a well and you can pump to your heart's content, even if that means you're pulling water in from underneath your neighbor's property. A farmer asked me if his neighboring farms were impacting his groundwater availability, and he had just paid $100,000 to drill a deeper well. And so I asked him, what was surrounding him. What were the farms? And they were large, industrial alfalfa farms, meaning the alfalfa, which is dried out and used as hay, food for cows. And then he proceeded to tell me about how big the wells were. They were 1000 feet deep, and they were six feet in diameter. And there were four of them, sort of north, south, east, west, surrounding his property. And he asked me if I thought that was impacting his falling water levels. And I said, "Absolutely." And there's not a heck of a lot that he can really do about it. So it was kind of tragic.

BELTRAN: Is that the case for most cities and states across the West?

FAMIGLIETTI: It is for many places. It's really a challenge because your neighbor can cause your well to go dry. You personally have no incentive to limit your pumping. Even if you're a great human being and you want to help conserve groundwater, you have no incentive, because if you don't use it, it will disappear. Your neighbor, who might be a big alfalfa farmer, industrial farmer with 1000 foot deep, six foot diameter well, you're gonna pump all that water and you're not gonna have any left. You know, it really needs attention.

Lake Mead’s water level is visibly dropping. (Photo: DylanMoz49, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BELTRAN: In recent years, we've seen record breaking temperatures across the West. I mean, I don't have to tell you, you're based in Arizona. How is climate change impacting the Colorado River Basin's groundwater?

FAMIGLIETTI: Climate change and warming temperatures are impacting groundwater in a couple of ways. One is that the basin is getting less rainfall. It's getting less snow melt, so less is coming in because it's warmer, evapotranspiration rates are greater, so there's more going out, and so that means lower stream flow, and that also means less opportunity to replenish the aquifers. That's one big way. The other is that as the Colorado River water availability continues to decrease, most regions that experience that decrease will try to switch to groundwater, which is totally fine if it's managed for the for the long term, but not so fine if it's unmanaged. And we're going to in certain regions, maybe drive it to disappear in the order of decades, rather than sustaining it for the long term.

BELTRAN: It's a real concern. Is the clock ticking here?

FAMIGLIETTI: The clock is absolutely ticking. And it's tough to say when the bomb explodes, because it comes down to a question of our choices, our policies, the rates at which we use the water, you know, the choices that we make. And are we going to, as individuals and as states, are we going to be worrying about how much groundwater we're leaving behind for our great grandchildren, or are we just going to worry about our children? How far out do we want to look?

BELTRAN: And how is the lack of groundwater impacting communities surrounding the river and the local ecology?

FAMIGLIETTI: Well, it's huge. The disappearance of groundwater leads to the depletion of our rivers. And so as we move to the southwestern part of the country, most of the rivers are dry, and the reason they're dry is because the groundwater levels have fallen so much, and so that has huge impacts on biodiversity. You know, the degree to which the communities are affected, it depends on how much groundwater they use. Some of them use a lot. I visited some small counties in Arizona, where they rely quite heavily on groundwater, and the local residents are seeing their water tables fall and having to pay $100,000 or more to dig a deeper well. And you know, chances are that one's gonna go dry, because there are a lot of industrial farms. This is in Western Arizona. There are a lot of industrial scale farms out there that are pumping a tremendous amount of water. So the disappearance is having a huge impact on the communities. And, you know, then think about agriculture as well. It's a challenge for agriculture, because, again, thinking about the demise of the Colorado River, then, will we still, we as a state or a nation still be able to grow the amount of food that we need to grow with a dwindling groundwater supply? And I think that question needs to be addressed.

BELTRAN: You know, agriculture is a key part of the southwestern US and across these desert areas of the United States. What role does it play when it comes to groundwater depletion and the health of the Colorado River?

FAMIGLIETTI: Agriculture uses a tremendous amount of water, and in the dry parts of the country, in the dry parts of the world, most of that water comes from groundwater, so it's having a direct impact on the demise of water availability in the Colorado River, and the burden is on us to figure out how to do things more efficiently, how to grow more food with less water, and also to think about prioritizing our crops. What are we going to grow, given that we have a decreasing amount of water? Are we still going to be doing the same amount of exports? These are all things that are impacting the groundwater and impacting agriculture. So I was just in Yuma yesterday and really learned about all the efforts they're making to do things more and more and more efficiently, try to get, you know, 80, 90% efficiency. They're well aware of the need to potentially tap into more groundwater. Right now, they have a lot of availability of Colorado River water, but they're preparing for a future in which they have to use more groundwater. And that's a critical story because many people don't really understand that most of the vegetables that we eat in United States and Canada between November and April, so it's beyond just the winter, come from Yuma. And so you know, if that water disappears, that farming stops, we will be hard pressed to replace those vegetables that we eat throughout the winter, you know, we're eating them on Thanksgiving, Christmas, holidays, you know, into the early spring. And so this is a food security and health security issue, really, for North America.

Because there’s little regulation of groundwater use, neighbors can dig wells to drain each other’s groundwater. This often leads to the construction of deeper and deeper wells. (Photo: Geoff Ruth, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

BELTRAN: So what steps need to be taken to save the Colorado River's groundwater? What can be done?

FAMIGLIETTI: There are some key steps. One, I think, is raising awareness amongst the general population and amongst our decision makers, so that everyone knows just how important groundwater is for food production and for the existence of these states and big cities in the southwest. We have to think about expanding groundwater protection. And we have to think about making sure where it is in place, that it actually works. As we've discussed and as we talk about in the paper, only 18% of the area of Arizona is covered by groundwater management. And there are some regions that are not covered by the Groundwater Management Act of 1980 in Arizona that are being rapidly depleted. And so I think our governor's office and our elected officials are going to have to have some serious conversations about expanding groundwater protection across the entire state of Arizona.

BELTRAN: What is one thing you want people to remember from your study and this conversation?

FAMIGLIETTI: One thing I think is really important for people to recognize is just how much groundwater we use, and it's almost two and a half times the amount of surface water that we use. And so when people are looking at the falling water levels in Lake Powell and Lake Mead, they should be thinking, you know, that's not even the worst of it. The worst of it is underground, and it's rapidly disappearing from beneath our feet. The other thing is that this is the water for the future, that groundwater. And if it disappears, it's not coming back. So we need to get people thinking about what sort of water inheritance do they want to leave for future generations? Do we want to burn through it all in the next 50 years, which could happen depending on some of our choices and the availability of Colorado River water. Or do we want to be thinking about century time scales? So these are choices we have ahead of us.

Canada and the United States depend on many vegetables grown in the southwest in the winter months, such as broccoli. (Photo: Rasbak, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

DOERING: That was Jay Famiglietti, Global Futures Professor at Arizona State University, speaking with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran. By the way, Yuma is known as the “Winter Salad Bowl” because some 90 percent of all the leafy greens grown in the U.S. during the cooler months come from farms around there. And in summertime, watermelons, cantaloupes, and honeydew melons ripen under the hot Yuma sun, and it takes a lot of water to make them so juicy!

Links

Explore Dr. Jay Famiglietti’s work

Listen to Dr. Famiglietti’s podcast, What About Water

Read Dr. Famiglietti’s study showing the decrease in groundwater

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth