June 13, 2025

Air Date: June 13, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

US Disrupts African Food Tech

View the page for this story

One of the development initiatives affected by the Trump Administration’s shutdown of USAID is the Soybean Innovation Lab, which works to improve soybean yields and production in Africa to help boost food supplies and farm income. Kerry Clark runs a mechanization development and fabrication training team at the Soybean Innovation Lab and joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss the work of the lab and why helping improve farmers’ yields is so fulfilling. (13:28)

Climate Injustice Floods Nigeria

View the page for this story

At the end of May a flood caused by torrential rain swept into Mokwa, a poor rural community in western Nigeria, leaving behind a horrific scene of death and destruction. Uwaisu Idris reported from the scene for Deutsche Welle and joins Host Jenni Doering to talk about how climate change is bringing more intense floods to Nigeria, and the responsibility of the rich nations of the world to assist poor countries that did not cause the climate crisis. (12:56)

Saving a Sacred Mountain in Mongolia

View the page for this story

Batmunkh Luvsandash, winner of the 2025 Goldman Environmental Prize for Asia, was raised as a Mongolian herder and later became an engineer who worked on mining projects in the mineral-rich country. But when he learned that the Mongolian government was planning to mine the sacred Hutag mountain, which is also home to the endangered Asiatic ass, he sprang into action. Batmunkh joined Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran (speaking through a translator) to share why protecting the area is so important to him. (06:27)

Pumping the Earth Dry

View the page for this story

A recent study finds the Colorado River Basin has lost a tremendous amount of water in the last two decades, in part from thirsty farms pumping water from deep aquifers much faster than it can be replenished. Lead author Jay Famiglietti, a Global Futures Professor at Arizona State University, spoke with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran about the “Wild West” of unregulated groundwater, potential solutions and why the rapid depletion of ancient groundwater threatens the water supply for future generations. (12:36)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

250613 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Kerry Clark, Jay Famiglietti, Uwaisu Idris, Batmunkh Luvsandash

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering.

African farmers face more poverty and hunger as USAID is shut down.

CLARK: When we taught people how to build this thresher, and then people started building them, in areas where nobody had been growing soybean, suddenly they started growing it and now they have income, because they can sell those soybeans to the poultry processors. You know, what's a drop in a bucket here can be life-changing in Africa, as far as providing knowledge or a piece of equipment.

DOERING: Also, protecting a mountain sacred to Mongolian nomads from mining.

LUVSANDASH, SPEAKING THROUGH TRANSLATOR: It's important to me, culturally and also historically, for Mongolian people, to believe in the land, to cherish their natural habitat, and that mountain is very special and dear to us. It's in our heart.

DOERING: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

US Disrupts African Food Tech

The Soybean Innovation Lab partners with researchers, farmers, and stakeholders across the private and public sectors to advance the production of soybeans in sub-Saharan Africa. Above, intergenerational farmers stand in a soybean field in Rotanda, Mozambique. (Photo: Soybean Innovation Lab).

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

In recent decades, humanitarian and development aid from the United States has fed the hungry, prevented and cured diseases and lifted people out of poverty around the world. And some say that has made the world a little safer, as well as kinder. But the Trump Administration has signaled it no longer values this “soft power,” and is shutting down the U.S. Agency for International Development or USAID. One of the USAID programs threatened by this decision is the “Feed the Future” Soybean Innovation Lab at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, which works to improve soybean yields and production throughout Africa. These efforts are more important than ever as climate disruption brings worsening droughts, floods and extreme heat. Kerry Clark teaches in the College of Agriculture at the University of Missouri and runs a mechanization development and fabrication training team at the Soybean Innovation lab, and she joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Kerry!

CLARK: Thank you for having me.

DOERING: So, Kerry, how is climate change impacting agricultural development and food security across sub-Saharan Africa?

CLARK: One of the big things that we see in Africa, and you know, I, coming in and out, don't see this, but I hear it from farmers all the time, is that the rain patterns have changed, and the tropics and the subtropics are all monsoonal seasons, so they have rains that come a certain time of year and last for a certain number of months, and that has, in the past, been very reliable. They knew when they were going to come, and it depends on, of course, where you live, when it shows up. And what's happened now is that either the rains come much later, or they come and then they stop, and then they might start again. But what happens is that people, you know, as they grow grain, and let's just take soy for an example, people save that seed and they grow it again next year. So they'll harvest and they have, let's say they have 100 pounds of seed. They're gonna eat 80 of it and save 20 to grow next year. So that 80 pounds, they have to make that last until the following year's harvest. So let's say they take the 20 and they plant it at the beginning of rainy season, and it rains three times and it stops. That seed dies. That's all they saved. Or what happens is, if the rain's delayed, then the 20 that they were saving for seed, they have to eat it before they can even plant it. So you end up, I think we're going to see a lot of hunger in upcoming years because of that seed versus grain issue and trying to make them both last until planting, they get in the ground and the next harvest. With climate change, it really affects people's ability to segregate out seed versus grain for eating and to be able to have seed to save.

DOERING: So why was this soybean lab created, and why focus on soy versus another crop?

CLARK: So there's actually, I think, 23 innovation labs that came under the USAID, and they deal with all sorts of different crops. So there was one for millet, one for sorghum, I think, one for common beans, one in general for legumes, peanut, so there was many, many different innovation labs. Ours was focusing on soybean because soybean is a crop that can be both eaten and sold as a commodity, and it can bring farmers out of poverty because it gives them an important crop to sell. The main market for soy is the poultry industry. And the poultry industry across the world is the fastest growing meat industry, and so soybean is incredibly vital, because unlike common bean or other types of beans, soy has an equivalent level of protein to meat. It's about 40 to 45% protein, while common beans are usually less than 15%. So per acre, you get a huge amount of protein with soybean. We focused on Africa, and we were not introducing soybean to Africa. It's been there for decades. What we were trying to do is get better varieties and get a better value chain and infrastructure system so that people can make more money and be more productive when they do grow soy.

DOERING: And remind me, does soy actually help fix nitrogen in the soil?

CLARK: Yes, soy is a legume. Yes, soy is a legume. It's a very high nitrogen fixer. So it's just like common bean or pigeon pea, or some things like that. The common beans tend to be more women's crops and grown for food for the family. They're not a commodity, being one that someone sells for a profit. So the soy is a commodity crop, so people can actually make money, and it can help build wealth. And that's one of the reasons USAID was focusing on that, because it has been a wealth builder across the world. If you look at what's happened to Brazil since Brazil stepped into the soy market, you know their income has greatly increased. Now, soy has a bad rap in Brazil, because people are basically cutting down the rainforest to grow soy. That's not soy's problem. I mean, that's not soy's fault. That's just because people wanted a crop that makes money. And so it doesn't matter if it's soy or corn or anything, but what they found was that they could grow soy well in Brazil. And so that's why it is soy, but it could have been any crop. In Africa, a lot of the arable land is, of course, already under production, but it's not very productive. Part of the problem in Africa is the age of the soil. It's the most weathered soil in the world, very low in nutrients that crops need, and soy has done well there compared to a lot of other crops like maize that are not indigenous. But the problem is their yield is about a fifth of its potential. And so that was what we were working on. Like, if you're gonna put the effort and use the land, then it's better that you get a higher yield.

Ongoing projects at the Soybean Innovation Lab include the testing of different soybean varieties in an effort to increase crop productivity. Our guest, Kerry Clark, says the current soybean yield is only about one fifth of its potential in sub-Saharan Africa. (Photo: Soybean Innovation Lab)

DOERING: That's incredible, that there was, 20%, a fifth of the yield that they could have if they were to employ some of these techniques?

CLARK: Yes. And we're not throwing inputs at this. Some of it's just, you know, even biological and like, the biggest thing we found was that people were getting very low yields because they weren't putting the plants close enough together. So we had a lot of production, agronomic things that we were able to influence that increased yield a lot that didn't require any inputs, just a different way of doing things. So some of the inputs that are important for soy is like rhizobium inoculant, and there are some places in Africa where they produce that. It's a very, very low cost input. It's just something that they grow, basically, you grow the inoculant and then you package it and sell it to farmers, and it makes a big difference.

DOERING: And just so people understand, I think you're talking about a bacteria?

CLARK: Yes, there's bacteria that live naturally in the soil that will have a symbiotic relationship with plants, and the plant provides the bacteria with carbohydrates that it gets from photosynthesis. And the carbohydrates are used for energy, just like us. We need carbs for energy. And then the bacteria, and for the case of soybean, it's called bradyrhizobium, that bacteria can utilize nitrogen from the atmosphere and put that into the plant roots, and then the plant, basically, we say the plant's making its own nitrogen, but in reality, it's a bacteria that's on the root that's providing the nitrogen from the atmosphere for the plant. And the plants need nitrogen for growth, because that's what amino acids and proteins come from, nitrogen.

DOERING: And Kerry, what does your work with the Soybean Innovation Lab involve?

CLARK: My part, of course, was the mechanization. So when we first got to start working with soy in Africa, and I think it was around 2013, 2014, we got a lot of feedback from farmers that said, we like soy, we make money with soy, but it's very, very hard to harvest, and most crops in Africa are hand-planted and hand-harvested still. And so we found some very good designers and fabricators in Ghana, and worked with them to develop a thresher that would process soybeans very rapidly. And we've done trainings all across the African continent on that from 2018 to 2020, and we've worked with the private sector to build manufacturing, and that's one of the big problems in Africa, is that manufacturing and the industrial sector is very limited, and so we've always focused on local manufacturing. Right before the USAID was terminated, we started increasing the number of designs that we had available, and we’d provide these free of charge to local manufacturers across the African continent. We do the original field testing of the design and give them feedback and input on what kind of farmers or what kind of crops each thing can be used for. But we've increased our product line to, we had just the thresher, and now we have a planter and also a pull-type combine. And that's kind of when we lost our funding. And so that pull-type combine was actually invented by a small farmer in Virginia, a man named Alexis Ziegler. And although it's patented, he's made it available for manufacturing in Africa. And so that was where we were heading when we lost funding.

DOERING: You had a lot of really exciting things in the works, it sounds like.

CLARK: Yes, we were having a lot of impact. So one of the goals of development is you always want to work yourself out of a job. So you want to build capacity where you're working, so that when you're gone and when the funding dries up, they can continue it. So we hadn't quite reached the point where they were completely independent of us. A few more years would have helped a lot. But I think Africa is heading in that direction, and it's very unfortunate now that the US has withdrawn funding for those kind of things.

DOERING: So what have you been hearing from farmers and communities about these cuts and how they're impacting their efforts to grow soy?

Kerry Clark provides training to soybean success kit recipients in northern Ghana. Clark says resources such as these kits can be “life-changing” in terms of creating income within African communities. (Photo: Soybean Innovation Lab)

CLARK: I mean, this is all pretty fresh, you know, the USAID cuts just came this spring. But immediately, you know, we lost all funding, people are still growing soy, but really quickly, they're going to find out now that they don't have access to the newest varieties, they don't have access to testing of inputs. Now, we had been working with the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, and they had been doing a lot of things with soy, and they will continue to do things with soy, but they were also funded a lot by USAID, and so it will also affect their efforts. So, this year for farmers in Africa, there's still varieties available, things are still the same, but next year they're going to see the effect that processes are going to have problems, the farmers are going to have problems, the input providers, everybody's going to have problems. And we've seen it here in the United States as well, that with the elimination of USAID, we have had huge cuts to Food for Progress and McGovern-Dole feeding programs and, you know, various programs that bought U.S. commodities and exported them through these USAID programs. So farmers are going to see effects in the United States. They're going to see it in Africa. That's the development side of USAID, but what's really devastating was the humanitarian aid side, where people are already dying. You know, they provided money for AIDS drugs, for malaria drugs, for a lot of medical vaccination, for research, for actually buying the drugs, and then, of course, USAID was also using a lot of that food that they bought in the United States to support feeding programs and refugee camps, and they supported the World Food Program, which is the biggest program for feeding people across the world. And that's all gone, and so that's going to cause, you know, very immediate suffering and death, and already has.

DOERING: So Kerry, what's next for you?

CLARK: So, we're trying to keep the Soybean Innovation Lab going, as well as we can. So basically, we're targeting people that have certain needs, and we're saying, we can meet your need, but because we don't have USAID funding, you may have to pay something to get this. I think all of us are kind of like, I won't be taking a paycheck for this. I'm doing it because I believe it's the right thing to do and people need it. So I've worked in research and extension in the United States for, I guess, 40 years now, and American farmers have it pretty good. They have very good processes. They have great machinery. They know what needs to happen. And so they don't really rely on the universities quite like they did maybe in the 40s and 50s when we brought in, hybrid corn and things like that. But in Africa, I can do just this teeny, little, smallest thing, and it can affect an entire village positively, like I might double their income because I told them to do something that they didn't realize would affect yields or growth. So I do it because of that. I don't need to draw an income. I need people to benefit from my expertise that I got the advantage of having, having been born, raised and educated in the United States.

DOERING: It must feel really good to be able to help so many people like that.

Kerry Clark teaches in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources at the University of Missouri and leads the Mechanization Division for the Soybean Innovation Lab. (Photo: University of Missouri)

CLARK: Yeah, I mean, when we taught people how to build this thresher, and then people started building them in areas where nobody had been growing soybeans, suddenly they started growing it, and now they have income because they can sell those soybeans to the poultry processors. You know, what's a drop in a bucket here can be life-changing in Africa, as far as providing knowledge or, you know, a piece of equipment or a new seed variety or something.

DOERING: Kerry Clark, PhD, runs a mechanization development and fabrication training team that includes three equipment designers from Ghana at the Soybean Innovation Lab. Thanks so much for joining us.

CLARK: Thank you for having me.

DOERING: Regarding its plans to shut down USAID, a recent State department cable reads, “The Department of State is streamlining procedures under National Security Decision Directive 38 to abolish all USAID overseas positions.” It also says the department “will assume responsibility for foreign assistance programming previously undertaken by USAID” as of June 15th. The Soybean Innovation Lab did receive some good news after the USAID cuts were announced. An anonymous donor offered roughly $1 million to help the Soybean Innovation Lab continue some of its work on a smaller scale for one more year. You can find out more on the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “USAID-Funded Soybean Lab Gets Lifeline After Cuts”

- The Guardian | “Trump Fires USAID Overseas Employees”

- Learn more about the Soybean Innovation Lab

[MUSIC: Orlando Julius, “Disco Hi-Life” on Disco Hi-Life, Hot Casa Records]

DOERING: Just ahead, Climate disruption is bringing devastating floods to western Nigeria. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Mulatu Astatke, “Kasalefkut-hulu – Stereo Master” on Mulatu of Ethiopia, Strut]

Climate Injustice Floods Nigeria

The aftermath of the flooding in Western Nigeria. (Photo: Uwaisu Idris)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

At the end of May a flood caused by torrential rain swept into Mokwa, a poor rural community in western Nigeria, leaving behind a horrific scene of death and destruction. Over 200 people were reported dead, and hundreds of others are still missing. The flood washed away homes, schools, and bridges. And in the aftermath of this climate-strengthened destruction, the future of the people of Mokwa hangs in the balance. Uwaisu Idris traveled to Mokwa to report on the situation as a correspondent for Deutsche Welle, and he’s back home now in Abuja, the capital of Nigeria. Uwaisu, welcome to Living on Earth.

IDRIS: Thank you very much. It's my pleasure joining you on this show.

DOERING: Well, thank you so much for being here. Now, can you describe for me what it was like when you first arrived in this community that had been devastated by these floods? What did you see?

IDRIS: It's a shocking situation when I first arrived. It's unbelievable to me, because the water has already gone, but the devastation within a few minutes, don't think it lasted up to an hour, everything is gone, because it's a local settlement whereby it's not a modern building, most of the houses are made by mud blocks. You see people in a devastation, in the confusion stage. Only one building I could see that, I've seen that is still standing, which we climb on top to get a clear view with our camera. And then the number of people who died, nobody can say, because there is no data. There are beggars, we are told, who were staying in one of the uncompleted buildings, over 100 of them. All of them are gone. They were all swept away by the rain, by the flood, and everybody is coming with his number of children, number of families that are gone. It's a nucleus set up that we have in Africa, large compound housing, almost everybody the same family, and everybody has his own children. Some are crying, some are yelling. Some could not even stand to talk. I interviewed somebody who is over 80 years, he said all his children are gone. His wife is gone, and he is sick. He's old. Nobody to cater for him. So myself, I was touched. I was affected by what happened. Because I don't know when I started crying at a point, but just to be strong that I know I have to work.

DOERING: That is just absolutely devastating. My heart goes out to these people. Uwaisu, in the aftermath of these terrible floods, you interviewed Azumi Usman, a mother who lost five children and her family lost 16 grandchildren in total. I can't imagine her pain. What did she tell you?

IDRIS: Azumi is in a state of devastation, as at the time I interviewed her, she cried several times, and she just managed to be strong to grant me that interview. All what she had was gone. The entire house was reduced to rubble, nothing she was showing me. This is where my house used to be. But I don't even think about the house, but I think about my family, my grandchildren, my children, they are all gone. I don't know where to pick [up] my life. I don't know where to start from. At that point, she said, I cried several times, but the tears have dried. But just imagining where to start her life. She doesn't know where to start her life.

DOERING: The water has receded, but there is so much devastation that's left, so much loss. What do the people of Mokwa hope for at this moment?

IDRIS: The most immediate need for them is food and shelter, because some of them are sleeping there. It rained when I was there, and you could see how they were scampering to see where to hide. Some know where to go and hide. Some had to climb on trees that are around there until after the rain, and you have only one cloth you cannot change. So you have to wait for that cloth to dry on your body. So that is the situation.

DOERING: You know, elsewhere in the broadcast, we have a story about how the cuts to USAID are impacting African farmers, who often have just enough grain saved to make it to the next harvest. What's the situation that Mokwa farmers are facing now in the aftermath of these floods?

IDRIS: It's more devastating for them, because already, the USAID cut has affected so many farmers in Nigeria because of the intervention they've been doing over the years. Just overnight, that has stopped, and now this is a community whereby is the beginning of rainy season. The tradition is, you save what you produced to last you up to the time when you are going to start even early harvesting. They haven't even planted anything, and their entire saving for what they are going to eat is gone. And then the USAID intervention has stopped. So it's a double jeopardy for them, because if that intervention is still running, they may be able to fast track certain things. They will get seedlings, they may get fertilizer, they may get even technical aids on how to start and where to start. But that is not there. That window is totally shot. It's a serious situation.

DOERING: Right, I mean, any of the grain that they were saving to eat, any of the grain they were saving, the seed they were saving to plant this season, that is all washed away. They have nothing.

Mokwa residents use shovels, hoes, and other tools to search through rubble. (Photo: Uwaisu Idris)

IDRIS: Yeah, they have nothing. Everything is washed away by the flood.

DOERING: Now, in recent years, Nigerian communities have been experiencing severe floods, resulting in hundreds of deaths. How is climate change making communities with poor infrastructure even more vulnerable?

IDRIS: Climate change has been affecting Nigerian communities in a worse situation of recent because the mitigation method is not yet there. There are so many promises of mitigating climate change. Yeah, disasters doesn't knock at your door. It can happen anytime, but you can foresee that there might be flood based on the predictions, because Nigerian Meteorological Agency has already predicted about some of the areas that might. It has released a report which indicated 31 states in Nigeria, including Niger State. And Mokwa is close to the fringes of River Niger, there are certain areas that used to experience flood, so it's really a devastating situation. And climate change is becoming more and more real because the temperatures are going high every year. Like this year, we had so much heat in Nigeria, even as at the time I was in Mokwa, it was very hot in the afternoon. I had to look for a hat to use to be able to have some shield on my head, it's really, really hot. Why? Because of climate change. You have so much rain within short time whereby the drainages cannot contain that amount of rain that is coming at the same time, and then the mitigation is almost close to zero.

DOERING: You mentioned that mitigation of climate change is just not happening, and a huge part of that is the fact that, you know, a lot of the rest of the world has been pumping greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere for decades and decades, and now places like Nigeria are really suffering the consequences of that.

Displaced Nigerian flood survivors gather. (Photo: Uwaisu Idris)

IDRIS: How much is Nigeria contributing? How much industries does Nigeria has? Nigeria is very, very low in terms of that emission of gas. We've been having this COP to COP; this COP, that; the discussion will happen, and at the end, where do you see the implementation? So developed countries are the ones who are producing these greenhouse gasses, and now it's affecting Africa and third world countries more because they don't have the technology to even think of doing the mitigation. When agreements are signed, you don't see the implementation in reality to be able to take care of these unforeseen circumstances, of disasters that are happening as a result of climate change.

DOERING: You know, as the climate rapidly changes, there's a lot of talk about climate justice. What does Nigeria need from the international community to help it become more resilient against climate impacts that it had virtually no role in causing?

IDRIS: I think Nigeria needed a lot. Number one, when there is an agreement, let me give you a classical example. Developed countries, they have the capacity to do direct intervention. The recent organization that is working for the European Union, they reach out to me and ask me, How best do you think can we do intervention for the Mokwa people? I said, go through the community leaders. When there are international agreements reached, do not just dump whatever you think you are doing to the government, but rather see how you can go directly to get this climate justice. There are various ways. There are organizations that have been working, especially civil societies, that who are working on the environment. They know how people can benefit directly.

DOERING: It sounds like, almost like a grassroots system of aid is needed. You know, really small scale, like in individual communities, is where this help is needed.

IDRIS: Exactly, exactly, grassroots, so that you go directly to those who can benefit from.

DOERING: So Uwaisu, how much help are these devastated communities receiving from the international community?

IDRIS: Well, they, I know UNICEF is there. They have established their own camp, and then the International Committee of the Red Cross. They are also on the ground there. I heard that the European Union, they are also planning to send their own shipment. And then the Turkish Government also, they sent their own shipment. I don't know whether it has arrived. So, but there is need for more, because if you imagine this happen in any European countries, it will continue to be attracting attention more. I know how difficult it is by so many countries -- the economic meltdown, there is Palestinian issue, there is Ukraine, but life is life. There is need for more intervention by the international community to help these people, because they need to live. They need to pick [up] and continue with their lives under this devastation. Especially women and children, if you see the situation children are -- I don't know, it's, it's unexplainable by anyone on radio.

DOERING: So from what you have seen and reported, what do you think the road to recovery looks like?

IDRIS: The road to recovery is a long one. Some may end up not recovering, because those who are really old, and then women and children, orphans who lost their parents, and everybody is battling with his own problems, and knowing the economic situation the country is, the road to recovery is challenging, and it may take years. I have the fear that some may not even recover, because when you have this kind you are in this kind of devastation, and you have health challenges and you are not getting the needed support. Some are hypertensive, some are diabetic, and then you have this kind of life, life challenges. How do you marry the two together? That was why I said they need a lot of urgent help and assistance, but within the community, within the Nigerian government and the international community, so that they can pick [up] their lives and start something.

DOERING: Uwaisu Idris is a correspondent for Deutsche Welle. Thank you so much, Uwaisu.

IDRIS: Thank you, my pleasure.

Related links:

- Uwaisu Idris’ original report for DW

- Uwaisu Idris’ update on the Nigerian flooding

- A US press release on the withdrawal of USAID Foreign Aid

- More on how Nigeria’s weather has been affected by climate disruption

- BBC | “More Than 700 Believed Dead in Devastating Nigeria Floods”

[MUSIC: Sona Jobarteh, “Saya (Motherland – The Score)” on Fasiya, African Guild Records]

Saving a Sacred Mountain in Mongolia

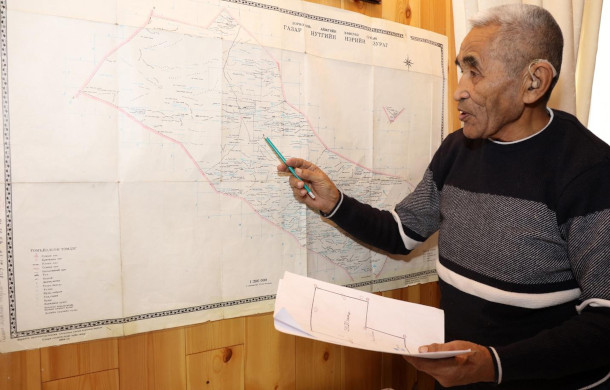

Luvsandash surveyed miles upon miles of desert, using his engineering skills to figure out the exact coordinates that needed protection. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

DOERING: The vast deserts, mountains and steppes of Mongolia are home to nomadic herders who cherish the land as sacred. But the land is also coveted for its deposits of gold, copper, zinc, uranium, and coal, that is sometimes mined illegally and with huge consequences for groundwater, grazing land and wildlife habitat. Batmunkh Luvsandash, winner of the 2025 Goldman Environmental Prize for Asia, was raised as a herder and later became an engineer who worked on mining projects. But when he learned that the Mongolian government was targeting the sacred Hutag mountain for mining, he sprang into action. Batmunkh spent months surveying the area, using his engineering skills to draw detailed maps of where most of the wildlife live. He then used these maps to collaborate with Mongolian officials to protect hundreds of thousands of acres of land, including 66,000 acres at the base of Hutag mountain. Batmunkh Luvsandash spoke through an interpreter with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

BELTRAN: I understand that the Hutag Mountain is culturally sacred. What does this region mean for you and your community?

LUVSANDASH (SPEAKING THROUGH TRANSLATOR): So we Mongolian people are a nomadic people that treat their land as sacred ground, because we believe that these mountains are sacred because they came under the water from long time ago, prehistoric times, and they are special because they came out from the ground, just like the Mount Everest used to be underwater pre historically, that mountain is very special and dear to us. It's in our heart. It's important to me, culturally and also historically, for Mongolian people to, to believe in the land, to cherish their natural habitat. And there's a lot of findings, historical and archeological findings are surrounding the mountain. There's cave drawings also discovered. And all in all, we value those things that are invaluable, and we like to keep that and culturally preserve them for the future generations.

BELTRAN: And Mongolia is home to several important species, including the endangered Asiatic wild ass and Argali sheep. How does mining impact these animals?

LUVSANDASH (SPEAKING THROUGH TRANSLATOR): Where I'm from, which is Dornogovi province. It's a region where there's not a lot of water. It's desert-like region of Mongolia, and because of having so many mining operations, especially the illegal ones, having no natural restoration policies and activities, they drive away these endangered species that are called Asiatic ass. We call it [inaudible]. And also they use lot of water used for their mining process, so it really just leaves competition for the natural habitats to be able to survive, and it's creating a lot of issues for the natural habitats and also for the farmers to be able to continue their farming operations. And a lot of these illegal minings contribute to consequences to the natural environments, and that's why these Asiatic ass, the Argali sheep is being endangered due to these mining operations and their uses of the land.

BELTRAN: And I understand that you worked as an engineer on mining and construction projects before embarking on this project to protect the Hutag Mountain from mining. What inspired you to use your knowledge for environmental protection?

LUVSANDASH (SPEAKING THROUGH TRANSLATOR): So people in Mongolia, when they reach 60 years old, they get retired, as is the case for me and I, for some reason, I was determined to protect my natural land where I was born, and I haven't stopped since then.

BELTRAN: And how does your family and your grandchildren feel about your work and activism?

BELTRAN: All of my grandchildren, I make sure that they believe in the mountain, in the work that I do, so they support me well, and in return, I help them to keep the tradition.

BELTRAN: He's a cool grandpa.

Luvsandash aims to pass on nomadic traditions to his grandchildren. (Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize)

LUVSANDASH (SPEAKING THROUGH TRANSLATOR): Thank you so much.

BELTRAN: So what would you like to tell the world about what's happening in your homeland?

LUVSANDASH (SPEAKING THROUGH TRANSLATOR): I would like to tell the world that, sure, there are countries that are underdeveloped, but they have natural resources, ability to mine for economic gain, and I understand the need for the mining, but I also have to let people know and remind them that there's the right way, there's the honest way to do certain things, especially when it comes to mining, because mining can leave so much environmental effect and wastes and hazards. And I just want the world and the people to know that there's a way that we can keep our environment and nature safe. And safe place for the generations to come and for them to live healthy. And to me, it's important to keep that balance.

BELTRAN: A true and amazing message.

LUVSANDASH (SPEAKING THROUGH TRANSLATOR): Thank you so much.

DOERING: That’s 2025 Goldman Prize Winner for Asia, Batmunkh Luvsandash, speaking through a translator with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

Related link:

Learn more about Batmunkh Luvsandash’s activism

[MUSIC: Morin Khuur Ensemble of Mongolia, “Mongolian melody” on Let the Mount Burkhan Khaldun Bless You]

DOERING: Coming up, Groundwater reserves in the American southwest are being depleted much faster than they can recharge. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Morin Khuur Ensemble of Mongolia, “Mongolian melody” on Let the Mount Burkhan Khaldun Bless You]

Pumping the Earth Dry

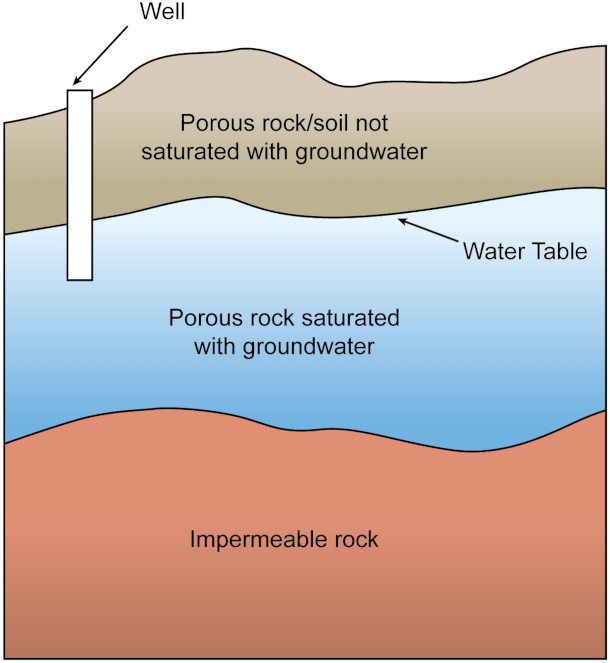

When people think of the plight of the Colorado River, they may think of the water on the surface, but Dr. Jay Famiglietti’s recent study showed that the river’s groundwater is also depleting quickly. (Photo: Doc Searls from Santa Barbara, USA, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

Even in deserts there are often large reserves of groundwater buried deep underground in aquifers that can take as many as thousands of years to fill. But our thirsty society is quickly burning through much of this ancient resource. A recent study published in Geophysical Research Letters found that the groundwater of the Colorado River Basin is being sucked dry largely by farms. And once those aquifers are drained, they’re not coming back any time soon. Parts of Mexico and seven U.S. states depend on the Colorado River Basin for their water. But it’s kind of a “Wild West” when it comes to groundwater in the West, since farmers and landowners have little incentive to conserve groundwater that’s mostly unregulated. Lead author of the study Jay Famiglietti is a Global Futures Professor at Arizona State University’s School of Sustainability and the former host of the podcast What About Water? He spoke with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

BELTRAN: You conducted a study showing that the Colorado River's groundwater is depleting. Talk to me about that study. And what are the big takeaways?

FAMIGLIETTI: We used over 20 years of satellite data from a satellite mission that we call GRACE. It's a NASA mission, and GRACE stands for Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment. And that particular mission is very good at helping us track changes in water availability and total water storage, all of the snow, the surface water, soil, moisture and groundwater. And it showed us that the Colorado River Basin has lost a tremendous amount of water over the last 22 years, as much as about 80% of Lake Powell and Lake Mead combined, and a lot of that was groundwater, something like 27 million acre feet, which is about the size of Lake Mead at capacity.

BELTRAN: You said 80%? That's a huge amount.

FAMIGLIETTI: It's an incredible amount of water. So I think the thing about groundwater is that it's out of sight and out of mind. And you know, there are a lot of people that are willing to take advantage of that and exploit that.

BELTRAN: And you know, part of your study discusses groundwater management and how it's effective in some places but not in others. How is groundwater management different from general water management?

Much of the Colorado River’s water is being used to grow alfalfa, a plant that becomes feed for livestock. (Photo: Philmarin, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

FAMIGLIETTI: Well, one of the big things is that it's really lagged behind for this reason that I just sort of alluded to, which is sort of out of sight, out of mind. So, you know, historically, most places have really focused on the water that they can see, which is the water in the rivers and lakes, and so that's been well managed, and the property rights have been worked out through the centuries, really. Groundwater is much later to the party, in the sense that it's taken a long time for groundwater management to happen in every state. I think California was the last, and that started in 2014. But even where we have groundwater management, the degree to which it's enforced or useful, really varies a lot over the United States. And I think a great example is Arizona, and only 18% of the state is covered by groundwater management. If you own property, you can drill a well and you can pump to your heart's content, even if that means you're pulling water in from underneath your neighbor's property. A farmer asked me if his neighboring farms were impacting his groundwater availability, and he had just paid $100,000 to drill a deeper well. And so I asked him, what was surrounding him. What were the farms? And they were large, industrial alfalfa farms, meaning the alfalfa, which is dried out and used as hay, food for cows. And then he proceeded to tell me about how big the wells were. They were 1000 feet deep, and they were six feet in diameter. And there were four of them, sort of north, south, east, west, surrounding his property. And he asked me if I thought that was impacting his falling water levels. And I said, "Absolutely." And there's not a heck of a lot that he can really do about it. So it was kind of tragic.

BELTRAN: Is that the case for most cities and states across the West?

FAMIGLIETTI: It is for many places. It's really a challenge because your neighbor can cause your well to go dry. You personally have no incentive to limit your pumping. Even if you're a great human being and you want to help conserve groundwater, you have no incentive, because if you don't use it, it will disappear. Your neighbor, who might be a big alfalfa farmer, industrial farmer with 1000 foot deep, six foot diameter well, you're gonna pump all that water and you're not gonna have any left. You know, it really needs attention.

Lake Mead’s water level is visibly dropping. (Photo: DylanMoz49, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BELTRAN: In recent years, we've seen record breaking temperatures across the West. I mean, I don't have to tell you, you're based in Arizona. How is climate change impacting the Colorado River Basin's groundwater?

FAMIGLIETTI: Climate change and warming temperatures are impacting groundwater in a couple of ways. One is that the basin is getting less rainfall. It's getting less snow melt, so less is coming in because it's warmer, evapotranspiration rates are greater, so there's more going out, and so that means lower stream flow, and that also means less opportunity to replenish the aquifers. That's one big way. The other is that as the Colorado River water availability continues to decrease, most regions that experience that decrease will try to switch to groundwater, which is totally fine if it's managed for the for the long term, but not so fine if it's unmanaged. And we're going to in certain regions, maybe drive it to disappear in the order of decades, rather than sustaining it for the long term.

BELTRAN: It's a real concern. Is the clock ticking here?

FAMIGLIETTI: The clock is absolutely ticking. And it's tough to say when the bomb explodes, because it comes down to a question of our choices, our policies, the rates at which we use the water, you know, the choices that we make. And are we going to, as individuals and as states, are we going to be worrying about how much groundwater we're leaving behind for our great grandchildren, or are we just going to worry about our children? How far out do we want to look?

BELTRAN: And how is the lack of groundwater impacting communities surrounding the river and the local ecology?

FAMIGLIETTI: Well, it's huge. The disappearance of groundwater leads to the depletion of our rivers. And so as we move to the southwestern part of the country, most of the rivers are dry, and the reason they're dry is because the groundwater levels have fallen so much, and so that has huge impacts on biodiversity. You know, the degree to which the communities are affected, it depends on how much groundwater they use. Some of them use a lot. I visited some small counties in Arizona, where they rely quite heavily on groundwater, and the local residents are seeing their water tables fall and having to pay $100,000 or more to dig a deeper well. And you know, chances are that one's gonna go dry, because there are a lot of industrial farms. This is in Western Arizona. There are a lot of industrial scale farms out there that are pumping a tremendous amount of water. So the disappearance is having a huge impact on the communities. And, you know, then think about agriculture as well. It's a challenge for agriculture, because, again, thinking about the demise of the Colorado River, then, will we still, we as a state or a nation still be able to grow the amount of food that we need to grow with a dwindling groundwater supply? And I think that question needs to be addressed.

BELTRAN: You know, agriculture is a key part of the southwestern US and across these desert areas of the United States. What role does it play when it comes to groundwater depletion and the health of the Colorado River?

FAMIGLIETTI: Agriculture uses a tremendous amount of water, and in the dry parts of the country, in the dry parts of the world, most of that water comes from groundwater, so it's having a direct impact on the demise of water availability in the Colorado River, and the burden is on us to figure out how to do things more efficiently, how to grow more food with less water, and also to think about prioritizing our crops. What are we going to grow, given that we have a decreasing amount of water? Are we still going to be doing the same amount of exports? These are all things that are impacting the groundwater and impacting agriculture. So I was just in Yuma yesterday and really learned about all the efforts they're making to do things more and more and more efficiently, try to get, you know, 80, 90% efficiency. They're well aware of the need to potentially tap into more groundwater. Right now, they have a lot of availability of Colorado River water, but they're preparing for a future in which they have to use more groundwater. And that's a critical story because many people don't really understand that most of the vegetables that we eat in United States and Canada between November and April, so it's beyond just the winter, come from Yuma. And so you know, if that water disappears, that farming stops, we will be hard pressed to replace those vegetables that we eat throughout the winter, you know, we're eating them on Thanksgiving, Christmas, holidays, you know, into the early spring. And so this is a food security and health security issue, really, for North America.

Because there’s little regulation of groundwater use, neighbors can dig wells to drain each other’s groundwater. This often leads to the construction of deeper and deeper wells. (Photo: Geoff Ruth, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

BELTRAN: So what steps need to be taken to save the Colorado River's groundwater? What can be done?

FAMIGLIETTI: There are some key steps. One, I think, is raising awareness amongst the general population and amongst our decision makers, so that everyone knows just how important groundwater is for food production and for the existence of these states and big cities in the southwest. We have to think about expanding groundwater protection. And we have to think about making sure where it is in place, that it actually works. As we've discussed and as we talk about in the paper, only 18% of the area of Arizona is covered by groundwater management. And there are some regions that are not covered by the Groundwater Management Act of 1980 in Arizona that are being rapidly depleted. And so I think our governor's office and our elected officials are going to have to have some serious conversations about expanding groundwater protection across the entire state of Arizona.

BELTRAN: What is one thing you want people to remember from your study and this conversation?

FAMIGLIETTI: One thing I think is really important for people to recognize is just how much groundwater we use, and it's almost two and a half times the amount of surface water that we use. And so when people are looking at the falling water levels in Lake Powell and Lake Mead, they should be thinking, you know, that's not even the worst of it. The worst of it is underground, and it's rapidly disappearing from beneath our feet. The other thing is that this is the water for the future, that groundwater. And if it disappears, it's not coming back. So we need to get people thinking about what sort of water inheritance do they want to leave for future generations? Do we want to burn through it all in the next 50 years, which could happen depending on some of our choices and the availability of Colorado River water. Or do we want to be thinking about century time scales? So these are choices we have ahead of us.

Canada and the United States depend on many vegetables grown in the southwest in the winter months, such as broccoli. (Photo: Rasbak, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

DOERING: That was Jay Famiglietti, Global Futures Professor at Arizona State University, speaking with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran. By the way, Yuma is known as the “Winter Salad Bowl” because some 90 percent of all the leafy greens grown in the U.S. during the cooler months come from farms around there. And in summertime, watermelons, cantaloupes, and honeydew melons ripen under the hot Yuma sun, and it takes a lot of water to make them so juicy!

Related links:

- Explore Dr. Jay Famiglietti’s work

- Listen to Dr. Famiglietti’s podcast, What About Water

- Learn more about groundwater

- Read Dr. Famiglietti’s study showing the decrease in groundwater

[MUSIC: Steve Martin, Steep Canyon Rangers, “The Great Remember (for Nancy)” on Rare Bird Alert, 40 Share Production Inc.]

DOERING: It’s just about time to celebrate Juneteenth and you won’t want to miss our Juneteenth special, next week on Living on Earth! Ecological and social justice advocate Rev. Mariama White-Hammond joins Living on Earth Executive Producer Steve Curwood to talk about faith, hope and resilience amid climate and environmental injustice.

WHITE-HAMMOND: As a faith leader, I love getting in the weeds. I can talk about solar policy and all of those things, but I think my first job is to remind us that we have a responsibility to each other and to all of the creatures with whom we’re in relationship to do better. To be better. And so I think we’re in a moment where humanity is being called to be better. And we need to get started manifesting that right now because we are on a deadline. The climate crisis is real and it’s happening right now. But I don’t believe it is too late for us to be our best selves. I have hope, even when a lot of the data does not bear out. And actually I think that’s part of what Juneteenth is about. It’s about continuing to have hope, continuing to lean in, even in the face of brutality, even in the face of oppression, even when you have been done very wrong. You do not allow it to crush your spirit.

DOERING: Recharge your spirit by tuning in next week for the Living on Earth Juneteenth Special!

[MUSIC: M.Fasol, “Cool Jazz” on Neo Soul Beats, Vol.1 (Relax Session), M.Fasol]

DOERING: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Daniela Faria, Mehek Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti McLean, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Frankie Pelletier, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Melba Torres, and El Wilson. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram @ livingonearthradio, and we always welcome your feedback at comments@loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth