America's Rural Sanitation Crisis

Air Date: Week of July 11, 2025

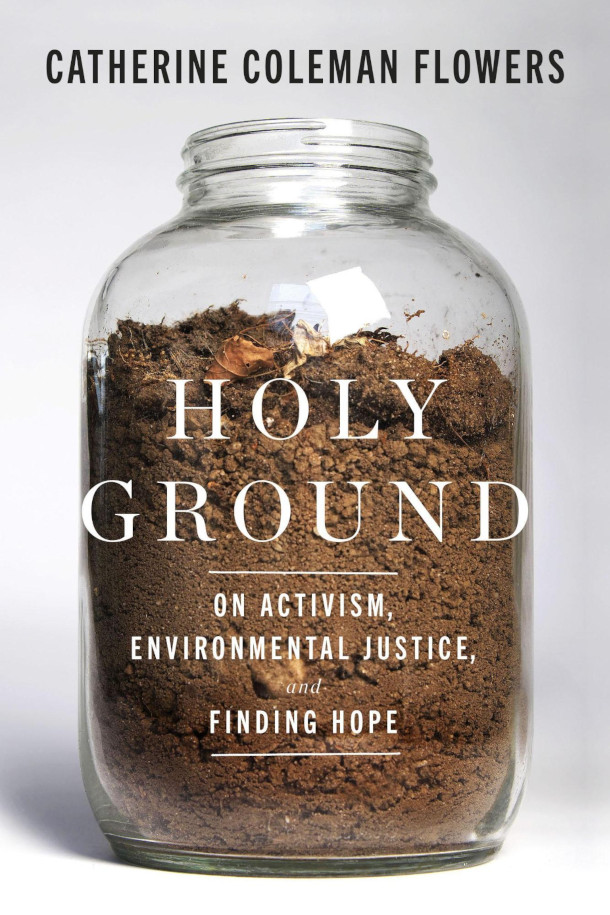

Catherine Coleman Flowers’ recent book is Holy Ground: On Activism, Environmental Justice, and Finding Hope. (Photo: Spiegel & Grau)

About a quarter of US homes use private septic systems, which can run you thousands of dollars. And more than a million people in America today are living without indoor plumbing, too often in appalling, unhealthy conditions. Catherine Coleman Flowers is working to change that. She is the founder of the Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice and has published a collection of essays called, Holy Ground: On Activism, Environmental Justice, and Finding Hope. She joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about her work to help rural families across America lead healthier and wealthier lives by improving sanitation.

Transcript

O’NEILL: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

When most Americans flush the toilet, their waste goes to municipal sewage treatment plants, paid for by taxes and fees. But it’s different in rural America. About a quarter of US homes use private septic systems, which can run you thousands of dollars for effective waste water management or composting. And more than a million people in America today are living without indoor plumbing, too often in appalling, unhealthy conditions. Catherine Coleman Flowers is working to change that. She is the founder of the Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice, which helps rural families across America lead healthier and wealthier lives by improving sanitation. She’s from predominantly Black Lowndes County, Alabama, where in 2023 public health researchers found as many as 80 percent of residents did not have access to reliable sewage systems. Catherine Coleman Flowers helped bring the federal government and the state of Alabama together to fund sanitation assistance for rural families in Lowndes County. But earlier this year the Trump administration cancelled that agreement. She has published a collection of essays called, Holy Ground: On Activism, Environmental Justice, and Finding Hope, and she joins us now. Catherine Coleman Flowers, welcome to Living on Earth.

CATHERINE COLEMAN FLOWERS: Thank you. Thank you.

CURWOOD: So let's go back now to your childhood there in Lowndes County. I think you were the daughter of a couple of civil rights activists?

CATHERINE COLEMAN FLOWERS: Yes, I am.

CURWOOD: And what was your childhood like, and how did their activism shape yours?

Catherine Coleman Flowers is an environmental and climate justice advocate. (Photo: Amanda Pitt)

CATHERINE COLEMAN FLOWERS: Well, my parents were like the jailhouse lawyers of our community. Everyone that had a problem came to them, but we also saw and they hosted a lot of people who were activists, like Stokely Carmichael, a lot of people that were part of SNCC would be in and out of our home. I got a chance to go to meetings. I didn't want to go to meetings, but my parents went to meetings. They weren't leaving us at home alone, so we went with them, and I guess a lot of things I learned and listened while I was attending those meetings about the importance of community and working with your community and working with the grassroots. But I also learned a sense of community by looking at the principles of SNCC, which I still carry today, and because of the work that my parents did before me in Lowndes County, I think I stand on their shoulders. So because of my parents and their activism and what I was exposed to, I think it prepped me to do what I'm doing today. And I think teaching only sharpened my tools as a community activist, to be able to go back and work in the community that I'm from.

CURWOOD: So probably not everybody knows the acronym SNCC, if they haven't paid attention to the civil rights movement, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. What did SNCC mean to you folks in Lowndes County? Because there's the history you know. On one hand, you have the image of the Black Panther, which emerges there, which is just fascinating, and this call for nonviolence, and you have Stokely Carmichael, so it was a pretty intense crucible. What was that like for you?

Catherine Coleman Flowers (left) and Lowndes County homeowner Charlie Mae (right). Charlie lives across from an open sewage lagoon in Hayneville, Alabama. Her yard will flood with sewage because of the outdated waste management system. (Photo: Lance Cheung, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Flickr, Public Domain)

CATHERINE COLEMAN FLOWERS: Well, you know, I grew up, my father was a vet. He believed in protecting his family, and like everybody in Lowndes County at that time, they had to have their own weapons to protect themselves, because Lowndes County was known as Bloody Lowndes. A lot of people died in Lowndes County, including Viola Lluzzo, who was a white housewife from Detroit, who was killed there. There was a seminarian who was killed there as well, Jonathan Daniels, who was white. So they didn't care whether you were Black or white at that particular time, they used violence to intimidate people. But what was significant about the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was that they were college students. Stokely Carmichael was a college student from Howard University, but there were many other college students that came to Lowndes County and helped the local people organize for the right to vote, and they organized their own political party called the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, and they took as their emblem the Black Panther. And the Black Panther actually did not come out of Oakland, California. It came out of Lowndes County and went to Oakland because they saw what was happening there. And some of the people that were in Oakland actually spent time in Lowndes County as well. So just to know that there were poor people who, for the most part, had been sharecroppers, were now running for office and studying democracy and using the Constitution after the signing of the Voting Rights Act, to take control of their own destinies was very important, and I think that Lowndes County is still leading the way in that regard as it relates to sanitation today.

CURWOOD: You write about the great rural divide, and, in particular, when you talk about this, you say that people were getting criminally charged for not having proper sanitary disposal. You call that the criminalization of poverty, and I mean beyond the impact of the monetary fees and the threat of jail time, how does that public health approach affect the people who are being targeted?

Catherine Coleman Flowers and Lowndes County homeowners lead a tour group learning more about the failing septic system in this Lowndes County property. (Photo: Lance Cheung, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Flickr, Public Domain)

CATHERINE COLEMAN FLOWERS: I think it makes them afraid. It makes them feel less than, and a lot of people, instead of talking about the problem, they tried to hide the problem, and they also took it personal. They thought that it was something that they created. But there are whole lot of things that led to that problem, and what we're trying to do is make sure that people are aware of that and they go and see it for themselves so that we can find a solution that is long term, because we haven't found it yet.

CURWOOD: Why is it that here in America that people live with septic systems, with sanitary systems, is the word that we use, that are like some poor place in the third world?

CATHERINE COLEMAN FLOWERS: I think that it's here because it's in rural communities. I think that in the urban areas, you can flush and forget in some cases, although climate change is changing that. You know, I was just in Mount Vernon, New York, where I went in 2021 because sewage was running back into the streets and in people's homes. But fortunately, they had a governor that found $150 million to get to the city, and they had a progressive mayor that wanted to change that, and consequently, they ended up changing it. They ended up fixing the problem. Instead of having 500 sewer backups annually, they're now cut it down to less than 50. But that was largely because of climate change. They're getting more rain. The infrastructure is failing throughout the United States, and we need to change that, and that's one of the things that we're trying to highlight. But in rural communities, people don't see it. They don't get to see what's happening there, because the media is not there. A lot of people have not visited rural areas. There are people that are making policies from the top down about rural communities and about monies that should go into rural communities. They haven't spent any time in a rural community. They don't know what it's like. So if you are living in a rural community, even in Massachusetts, a lot of people are on onsite septic. And when they're on onsite septic, it is the homeowner's responsibility in a lot of cases to maintain it, but there's more that go into it. In Lowndes County, we have high water tables. I'm sure in the coastal areas of Massachusetts, they have high water tables. There are coastal areas around the country where there are high water tables. With sea level rise, meaning that a lot of that water has been pushed underground. These systems don't function the way they were designed to function. But what we have not done is kept up with the technology and design systems that should work. Because what we found out initially, there were people that were straight piping, meaning that when they flushed their toilet, it goes straight out onto the ground. However, we also found, we did a house to house, survey that people had paid for onsite septic and it wasn't working properly. Meaning, when it doesn't work properly, it pushes the sewage back into their homes, comes back into a bathtub; it can come into a shower; it can just flood the home. We've seen that as well. So those are the problems that we have found. When we first started working on this in 2002, a lot of people thought that, oh no, it's just a problem with these poor Black people in Lowndes County who cannot afford septic. But it's more than that. We have found that this problem exists throughout rural America, and even when we were trying to bring attention to it, nobody was interested. The major media wasn't interested until we did a parasite study. We did that parasite study at Baylor's National School of Tropical Medicine, and we found hookworm and other tropical parasites in Lowndes County. And it became international news that the richest country in the world had these Third World conditions. Then people start paying attention.

Catherine Coleman Flowers received a MacArthur Fellowship Grant in 2020. (Photo: John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

CURWOOD: I think people, and I don't think I'm spoiling things to tell people in advance. They're going to find as part of your story that you have dealt on both sides of the aisle with important politicians. You're from Alabama. Jefferson sessions was a prosecutor, there a senator. And you talk about having a connection, having a dialog with Senator Sessions. And many people say, wait, wait, wait, this woman from the Black Belt of Alabama is dealing with Sessions? Didn't he like the KKK? And you say?

CATHERINE COLEMAN FLOWERS: What I'm saying is that I'm from Alabama, too. And being from Alabama, I'm trying to help get raw sewage off the ground. And if Jeff Sessions has the power to do that, and he understands the problem, I'm going to work with him. I think sometimes we don't have solutions because we're looking for the perfect. We will never have that. But the way he and I connected, I’d just moved back to Alabama, and I went to a town hall meeting that he hosted, and he was talking about what he was doing in Washington and how they had all this money available for rural communities. And I asked the question, where Senator Sessions, how can we get this money since it requires a 25% match and we don't have a tax base? How do poor communities and rural communities get access? And he came to me afterwards, and he said, Catherine, I'm glad you asked that question, because I've been asking that question too. I don't know the answer. I said, 'Well, we can work together on finding this answer.' And then at a point, because that's how our dialogue started, he told me he grew up poor in Wilcox County, Alabama, and he started telling me some things about his own upbringing, that which was similar to mine. At that particular time when I started raising issues around the wastewater situation, I started getting death threats. Senator Sessions would send people down from Washington to go to public meetings with me, to let people know that he was there standing with me as well. I had to make a decision. Do I turn my nose up and don't do anything? People have to keep in mind I'm from Lowndes County first. Because I'm from Lowndes County first, I've learned a few things. One of the things is that we have to leave room for transformation. I learned that from Bryan Stevenson. You know, and if I'm a Christian, I have to also be forgiving. I feel that sometimes, we have to, people can learn from us. They may not know because of the kind of folk that they've been around, but if they spend time around someone who is selfless and not interested in politics, but interested in finding the things that we have in common and trying to work from that point, I think we would have less strife and less division in this country.

This mobile home in Lowndes County, Alabama, is being flooded by sewage from its failing septic system. (Photo: Lance Cheung, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Flickr, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Tell me the story that you have in your book about the visit you had from Bernie Sanders to try to understand about the sanitary problem.

CATHERINE COLEMAN FLOWERS: Well shortly after the parasite study was released and went public, we had a visit from the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty. And when he came to Lowndes County, he actually said that the conditions he saw there were conditions he never expected to see in America, but he had seen in many Third World countries. After he left Lowndes County, he went to Washington, and he met with Senator Sanders and shared with him what he had seen. And I heard from Senator Sanders. He called me and asked me to come to Washington to speak at a town hall meeting. And I took that opportunity, not only to go there, but to invite him to come to see it for himself. And he did. And when he came to see it, like I tell everybody, when you see it, you don't unsee it. And he had the opportunity to go and visit in a home of a family who lived in a single, wide mobile home. The house was full of mold. The floors were weak. She was straight piping. She had to put traps inside her home to catch opossums that were coming inside of her home. Her daughter was nine years of age and sleeping on a CPAP. So if the the conditions were horrible. But a lot of politicians and a lot of wealthy people never get a chance to go and see the other side and see how people live in those conditions. But Senator Sanders got a chance to see it. But I think that what happened as a result, he saw it, he wanted to help, and I got a call from him later, asking me to join the Biden Sanders Unity Task Force, because he was withdrawing from the presidential race, and asked me to get on this task force that was headed by John Kerry and AOC to talk about environmental justice and climate change, and that gave me the opportunity to really push the sanitation issue to the national level, and hopefully to a level of policy where maybe some eventual solutions were going to come, because there were people listening that can make a difference if Biden had won the election, and he did.

View on Threads

CURWOOD: The Trump administration recently scrapped the work that you did with the Biden administration with the state of Alabama to correct the sanitary issues right there in Lowndes County and some of the other Black Belt communities in Alabama. What is that case about? And how does this announcement make you feel? And of course, what are these communities to do? What's the way forward for them?

CATHERINE COLEMAN FLOWERS: After the parasite study came out, we filed a complaint with our attorneys at Earthjustice, with Health and Human Services, and that complaint ended up being investigated by DOJ under the Biden administration, and they came to a resolution with the state Health Department to find a solution to the wastewater problem. That solution was to put money into the county, and some of it went through the state for the purpose of putting in septic systems for families that could not afford it, and to prioritize that the households that needed them the most. And recently, the Trump administration announced that they were ending this resolution, and they characterized it as an illegal DEI initiative, which I thought was a mischaracterization of the problem. It is striking a nerve with people, because people are now understanding that it's not just Lowndes County. This particular initiative led to not the resolution itself, but the Biden administration had announced a Closing of Wastewater Access Initiative that included 11 counties from throughout the United States, including areas in West Virginia that were having problems as well with sanitation. And what does it mean? Well, the Health Department says that they were going to continue to put in place septic systems as long as the money lasts. So we don't know how much money has been spent and how much money still remains and how many families will be impacted. But clearly we will continue to have a problem with sanitation in Lowndes County.

CURWOOD: What does it cost to have appropriate sanitation? What would it cost to really remedy it?

CATHERINE COLEMAN FLOWERS: The last septic system that we tried to work on and have put into a home was actually the home of the person that Senator Sanders went to visit, but unfortunately, she died of COVID. But that particular system was around $28,000. We've seen them anywhere from $12,000 on up. We're talking about families that are among the poorest families in the U.S., and they were not making that type of money. That was in some cases, half the income for the entire year for them and and therefore they couldn't afford it. But I think what I've seen is that in this country, we pay for what we want, and if we should never say that it's too expensive to put in place sanitation for poor families because of the cost. We don't care what we pay for more affluent areas. There's probably no affluent area in the United States, especially no urban area, that has a sanitation system that was not paid for by taxpayers’ money.

Catherine Coleman-Flowers (right), Vice Chair of the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council, arrives with President Joe Biden (left) to an Executive Order signing on environmental justice, Friday, April 21, 2023, in the Rose Garden of the White House. (Photo: Cameron Smith, Official White House Photo, Flickr, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So as we move towards closing here, how does your faith and how do the matters of faith really help us at this juncture?. We have tremendous political turmoil. We have things like failed sanitation in perhaps the most affluent nation on Earth. We seem to be in a host of trouble in a number of different ways. How can faith move us forward from this point? What's your advice to people who might want to seek faith as a way to move forward?

CATHERINE COLEMAN FLOWERS: I think we should have faith in action, because my father used to tell me, Catherine, first you pray and then you act. Because he said, if you make one step, he'll make two. And I believe that. I believe that. I think we have to be engaged, we have to be active. And when things get hard and our anxiety gets the best of us, that's when we stop and pray. We stop and pray, and then we ask for guidance and direction, sleep on it and get up and be active the next day.

CURWOOD: So we solve it by moving?

CATHERINE COLEMAN FLOWERS: Yes and taking action, but some type of movement, whether it's voting, writing an op-ed, whether it's going organizing, whether it's talking to young people, getting them engaged, whatever your action is, because there's so much to be done on so many different levels that there's room for everyone to do something.

CURWOOD: Catherine Coleman Flowers is the author of Holy Ground: On Activism, Environmental Justice, and Finding Hope. Thank you so much for joining us.

CATHERINE COLEMAN FLOWERS: Thank you for having me.

Links

Find a copy of Holy Ground (Affiliate link supports LOE and indie bookstores)

The Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice

Web page link on Lowndes county from EJI.org

Yahoo News | “President Biden, Catherine Coleman Flowers Speak on Environmental Justice”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth