Huge Danger from Permafrost Loss

Air Date: Week of September 12, 2025

The boreal forests of the far north store as much carbon as has been released by human civilization since industrialization. (Photo: USFWSAlaska, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

With the Arctic warming four times as fast as the rest of the globe, and fires now routinely burning large swaths of northern forests, carbon stored in permafrost is rapidly escaping into the atmosphere where it can warm the planet even faster. Edward Alexander, Senior Arctic Lead at the Woodwell Climate Research Center and a Co-Chair of the Gwich’in Council International, speaks with Host Jenni Doering about the enormous climate risks of permafrost loss and how Indigenous cultural practices can help protect this vital resource.

Transcript

DOERING: In the far north of our planet, boreal forests and permanently frozen earth, or permafrost, store massive amounts of carbon and keep our global climate in a delicate balance. But with the Arctic warming four times as fast as the rest of the globe, and fires now routinely burning large swaths of northern forests, that locked up carbon is rapidly escaping into the atmosphere where it can warm the planet even faster. Scientists including the late ecologist George Woodwell have been sounding the alarm about this dangerous feedback loop for decades, though for too many in our society, the Arctic is out of sight and out of mind. But indigenous peoples of the Arctic, who are often the first to feel these effects, are raising their voices to spread awareness about their home’s vital role in maintaining a livable world. Edward Alexander is the Senior Arctic Lead at the Woodwell Climate Research Center and a member of the Gwich’in indigenous tribe in Alaska. He’s also a Co-Chair of the Gwich’in Council International, and he joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Edward!

ALEXANDER: Thank you. Thanks for having me, delighted to be here.

DOERING: So tell me a little bit about where you live now and where you grew up. What kinds of climate impacts has your community been facing in the last few years?

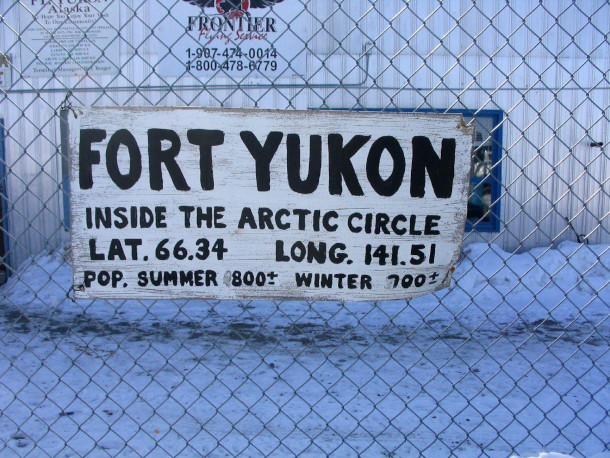

ALEXANDER: So I grew up in a remote, fly-in only community in northeastern Alaska called Fort Yukon. It's eight miles north of the Arctic Circle, and the furthest north the Yukon river goes. It's at the conjunction of the two largest watersheds in Alaska, the Yukon River and the Porcupine. About 65% of the Yukon flats have burned since about 1964, we're talking about an area that's burned equivalent to four Delaware's worth of land just in our immediate neighborhood. Our area has warmed 8.8 degrees Fahrenheit already, just in my lifetime. And so when we think about Arctic amplification, and the Arctic warming four times faster than the global average, you know, this is very pronounced in Gwich'in homelands and the in the Yukon flats in Alaska, the Yukon territories in the Northwest Territories.

DOERING: So we're talking about multiple threats to the Arctic. It's warming four times faster than the planet overall. Then something that's happening is boreal forests are catching on fire. What is a boreal forest?

ALEXANDER: The boreal forest is the largest forest on Earth. It's mostly spruce, with willow and some quaking aspen and some birch. So there's a lot of indigenous communities, not only in Alaska, but also in Canada and in Russia, that depend on this boreal forest for cultural survival, but also just basic existence, finding food and other kinds of things. And so when you think about the boreal forest, which most people don't, we have to think about what it contains. And so it contains as much carbon in the forest as has been released by all human activity since industrialization.

The remote, fly-in only community of Fort Yukon has experienced the impacts of climate change firsthand. (Photo: Kirk Crawford, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

DOERING: Wow.

ALEXANDER: So every car, every plane, every light bulb that's been turned on, right? Yeah, it's an, it's a stunning amount of carbon that's currently stored in this forest. And then it becomes a little more complicated as we go down into the, what's underneath this forest. That's kind of what makes it, even a little more special. The boreal forest has this thick organic layer. And if we think about what's in this organic layer, and why isn't it just releasing this carbon into the atmosphere, is because it's frozen as permafrost underneath the boreal. So this permafrost is very special in that it contains more than twice as much carbon that has ever been released by all human sources, and so people are not aware that it's a frozen foundation that this current society and civilization is built on. People are not aware that every person on Earth depends on permafrost storing vast amounts of carbon, everybody on Earth is dependent on the boreal forest shielding this permafrost from thawing.

DOERING: Yeah, I mean, we sometimes hear permafrost referred to as a carbon bomb because of all the carbon dioxide and methane that it could potentially emit as it thaws.

ALEXANDER: It also releases nitrous oxide, which is 250 times more powerful as a greenhouse gas than carbon. And there's another kind of permafrost that I think probably most of your listeners may not have heard of and that I'm particularly concerned about, that indigenous communities in the north are particularly concerned about, that you know, our folks at Woodwell Climate Research Center are also very concerned about, which is yedoma. And yedoma is a type of ice-rich permafrost, that has a lot of carbon in it, and, you know, has the potential to create huge warming effects for the entire planet, particularly because it thaws as methane, largely, instead of as carbon, like other permafrost.

Permafrost is also a vital carbon store for the planet. When permafrost thaws, it can release greenhouse gases and cause local ground collapse. (Photo: Boris Radosavljevic, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: So not all permafrost is created equally.

ALEXANDER: No, no, yeah, you're kind of run of the mill permafrost is like, we generally consider like one to two meters deep. Yedoma, on the other hand, can go hundreds of meters deep. That's an ancient carbon storage that can be 150-200,000 years old or more. And so it's been there through ice ages and through warm cycles. And so it's seen a lot of fire during the time that it's been on the planet, but in the Yukon flats recently, what we've started to see is that the fire has burned so intensely and so deeply that it's burning off all of the vegetative layer and duff layer above yedoma, and then yedoma is starting to collapse. And something else of particular concern to me is that none of this is included in modeling for climate change, and so the wildland fire crisis across the circumpolar is still considered like a stable ecosystem by climate researchers generally, and permafrost is considered a stable system, and it's important that we understand that there are changes happening here. The Yukon flats is very indicative of that, which is why the United States Fish and Wildlife Service has moved to protect yedoma as a value at risk in the region. A yedoma deposit thawing could be more emissions than small countries, or even, you know, if all of the yedoma thaws, it'd be more, more emissions than all of the countries.

Edward Alexander speaks at COP29 in Azerbaijan in 2024. (Photo: Pavel Sabudzinsky / Hi Impact)

DOERING: And what exactly is happening here with climate? I mean, I understand that there's so much warming happening in the Arctic, so what is it in that process that, in that warming, that leads to this permafrost thaw?

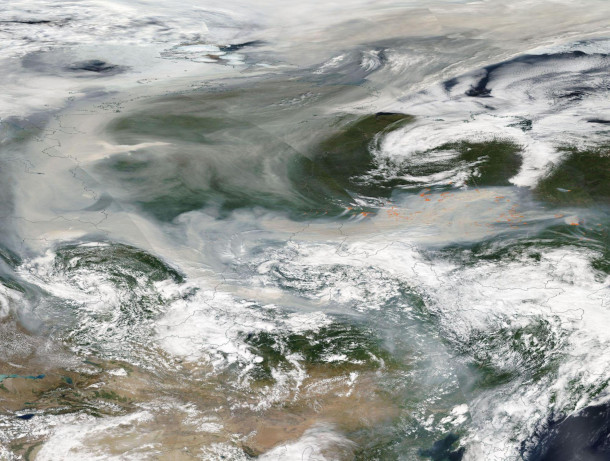

ALEXANDER: Well, I think one of the things, well, you have the average air temperature being a lot higher. The main driver that I've been concerned about for a while is the impact that wildland fire has on permafrost thaw and on yedoma thaw, particularly. Most people don't think about wildland fires in the Arctic until there's smoke blowing into New York City or into Boston or into DC, and so they experience it as a smoke event. The other side from where that smoke is originating, the emissions are huge, right? And then you think about, what are the after-effects? What's the post-fire world look like in the Arctic? And so what happens is, this layer of vegetation gets burned off, and we're seeing it burn more deeply than ever, and it burns down into this duff layer, which is like an organic mat that is on the forest floor and so forth. And the problem with a duff layer burning is that it's the insulation, essentially, that keeps permafrost frozen, so if you have imagine your cooler, and you're out there and you've got, like, your frozen stuff or your cooled stuff, and you take the cooler lid off, and then everything inside starts to spoil, and that's essentially what's going on with permafrost. And so you have these areas where a fire can come in and burn off all of this insulation, a huge fire, because fires in the Arctic have gotten to be massive. And then year two, year three, year four, year five, of that fire, there's still emissions occurring from those fires. At that point, it's not a flame, but you're seeing permafrost thaw, subsidence, ground collapse. You're seeing areas where there's large like landslides into rivers, affecting water quality, affecting fish in those rivers. And that's really this kind of intersection of where wildland fire has this profound impact over vast areas of land, and then it has this secondary effect of having, generating this opportunity for permafrost to thaw, and that's an opportunity that we want to prevent.

Intensifying wildfires in Arctic boreal forests threaten these crucial carbon stores on the planet. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, MODIS Land Rapid Response Team, NASA GSFC, Public domain)

DOERING: You know, what are some things we can do that might help here? I mean, are there indigenous practices that can help with wildfire management? And this connected issue of the permafrost thawing?

ALEXANDER: You know, we've seen 174 million hectares burn across the circumpolar boreal. 174 million acres is equivalent to the entire state of Oregon burning and then also the entire state of California and Nevada and Utah and New Mexico and Arizona all combined. When we think about this problem, it's not a chainsaw problem, it's not an ax problem. It's not like you can just get a bunch of men and women out in the field and cut fire line and have like, this problem be solved. And the kind of interventions that we've normally had for a wildland fire in the south, like digging a trench, if you dig a trench to stop a fire in California, that's an effective solution there. In the north, and in the Arctic, if you make the same kind of fire line, you can create a long lake because you're removing the surface layer of insulation, essentially from that land. So we have to be really thoughtful about it. And I think one of the things that is really promising to manage wildland fire across the Arctic is using cultural practices of indigenous peoples across the circumpolar north. One such practice is Gwich'in cultural burning, Gwich'in cultural fire, practiced early in the spring, and as spring comes around, the areas that melt first are these meadows and lake edges. This area becomes uncovered with snow from the heat of the sun in the springtime, but there's still snow in the forest. And so traditionally, our people would go out and burn these meadows and burn these lake edges. It helps to, increase the forage capacity of the land, so the plants that come back are much more nutritious for all the animals. And so that's very important for people who depend on these animals to survive too, right? And so that's traditionally why Gwich'in did these practices. But in the modern context, it creates a fire break. So in the summertime, if you have a fire burning through the forest, and then it comes across an area that's already burned in the spring, it's not going to burn twice, right? You've already burnt off all of the dry fuel in that area. The other reason why it's an important intervention is that when we think about protecting the carbon in that soil, this practice is done early in the spring when the ground is still frozen, and so you're protecting all of the carbon in the soil, all the carbohydrates and the roots from the plants that have stored all winter. So as far as limiting fire extent, limiting fire severity, so preventing these fires from burning down into some of these deeper peaty areas, exposing the areas beneath it to permafrost thaw or yedoma thaw, even more worrisome, and so part of it is Gwich'in indigenous practices from other places typically promote mild fire instead of wildfire.

Edward Alexander is the Senior Arctic Lead at the Woodwell Climate Research Center and a member of the Gwich'in indigenous tribe in Alaska. He is also a Co-Chair of the Gwich'in Council International. (Photo: Eric Lee)

DOERING: You know, Edward, it sounds really challenging to live in your home right now, as the climate crisis accelerates and causes all of this damage to the land, to the planet as a whole. What gives you hope and what keeps you committed to fighting such a tough fight?

ALEXANDER: Well, I think that the alternative is not something that I'm willing to concede. You know, for people in the Arctic, we've dealt with profound change on an order of magnitude that other people across the world have not had to reckon with yet. And I think part of it is, in order to have some of the hope that I have and optimism I have is, I decenter humans from the discussion a little bit too, like it's not just about us. People always say, well, we do this for our children in the future. That's true. I have children and I care about their future. I also care about the animals and their futures. I also care about the plants and their futures, right? And we can work together. Not fight, not fight the issue. That's a real, it's like a western idea. We're gonna have a battle. We're gonna fight this thing.

DOERING: Yeah.

ALEXANDER: Well, no, don't, no. I'm from a small indigenous community, and guess what? You learn in that community is you've got to work together. And if we understand that we got to work together, we got to be kind on this issue, we're going to get there. We will fix these problems.

DOERING: Edward Alexander is the Senior Arctic Lead at the Woodwell Climate Research Center. Thank you so much, Edward.

ALEXANDER: Thank you for having me, delightful to be here.

Links

Read more about Edward Alexander’s work at the Woodwell Climate Research Center

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth