September 12, 2025

Air Date: September 12, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Trump Stalls Offshore Wind

View the page for this story

The Trump Administration is putting offshore wind energy on hold by canceling grants, cutting tax credits and revoking permits for projects that are nearly complete. David Cash, the former Region One Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency under President Biden, joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss the economic impacts to port communities and his view that the US is ceding the opportunity to be a global leader in renewable energy. (12:45)

A Tale of Two Turtles

View the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Don Lyman is back in classrooms teaching biology as a substitute and incorporating his passion for herpetology wherever he can. But one unusual classroom turtle presented an identification puzzle, and a teaching moment that he recounts in his essay “A Tale of Two Turtles.” (03:58)

Huge Danger from Permafrost Loss

View the page for this story

With the Arctic warming four times as fast as the rest of the globe, and fires now routinely burning large swaths of northern forests, carbon stored in permafrost is rapidly escaping into the atmosphere where it can warm the planet even faster. Edward Alexander, Senior Arctic Lead at the Woodwell Climate Research Center and a Co-Chair of the Gwich’in Council International, speaks with Host Jenni Doering about the enormous climate risks of permafrost loss and how Indigenous cultural practices can help protect this vital resource. (14:07)

BirdNote®: The Auspicious Chime of the Bare-throated Bellbird

/ Nick BayardView the page for this story

The exceptionally loud, metallic call of the Bare-throated Bellbird can be heard almost a mile away. BirdNote®’s Nick Bayard reports that the Bare-throated Bellbird is Paraguay’s national bird and has inspired Paraguayan harp music. (01:59)

The Health Risks of Noise

View the page for this story

Human-made noise is bad for our health, disrupts our natural world, and hinders our ability to connect with one another. Author and journalist Chris Berdik joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss his book Clamor: How Noise Took Over the World and How We Can Take It Back, which explores the hidden costs of unwanted sound and advocates for turning down the volume on human-made noise. (13:26)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

250912 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Edward Alexander, Chris Berdik, David Cash

REPORTERS: Nick Bayard, Don Lyman

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The Trump administration holds back offshore wind just as it’s taking off.

CASH: It’s this economic question where we’re ceding the opportunity to be global leaders in renewable energy development, deployment and job growth, and we’re essentially saying, nah, we don’t want to do that.

CURWOOD: Also, wildfire threatens vast stores of frozen carbon in the far north.

ALEXANDER: So, this permafrost is very special in that it contains more than twice as much carbon that has ever been released by all human sources. It's a frozen foundation that this current society and civilization is built on.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Trump Stalls Offshore Wind

The Trump Administration issued a stop-work order for an offshore wind farm in development off the coast of New England, Revolution Wind. The final product, like this one in Europe, would have provided clean energy for thousands of homes. (Photo: Andy Dingley, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The American Clean Power Association says there is enough offshore wind capacity in the works nationwide to affordably power 22 million homes. But the Trump Administration is putting this abundant renewable energy source on hold by canceling grants, cutting tax credits and revoking permits. And just this August, the administration issued a stop-work order against a wind farm off the coast of New England that was already 80% complete. Here to talk to us about the impact of these actions is David Cash, the former Region One administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency under President Biden. So David, wind power was supposed to help us meet the challenge of the climate emergency, but the White House seems to be saying no, huh?

CASH: Yeah, well, in the last several weeks, there have been a lot of announcements by the administration, not just about particular projects, but a whole range of actions that it's taking to stop the wind industry, just as it's taking off. And maybe what you're referring to is the stop-work order for Revolution Wind. That's a large wind farm off the coast of Rhode Island and Connecticut. Already, private sector has invested over $4 billion in the construction of that farm. But the stop-work order is only one of many. In a cabinet meeting, the President instructed all of his agencies to look at the various tools that they have to stop wind as well. For example, Health and Human Services Secretary Kennedy says he will explore the electromagnetic fields from wind turbines, which have scientifically been shown not to be significant. The Department of Defense Secretary is looking at national security issues, and again, those issues have been exhaustively studied. Each of these projects that are targeted, Revolution Wind, for example, has been nine years, nine years of permitting, working with federal agencies to determine what kinds of problems might exist and if there are any problems, how to mitigate them. Another action that was taken was cancelation of all federal funds that are going to offshore wind related activities. So the Department of Transportation canceled over $600 million of grants that were going to rebuild ports, and all up and down the East Coast, there are ports that have come on hard economic times, and were looking to offshore wind as the new industry to boost their economy.

DOERING: Yeah. I mean, not far from me in Salem, Massachusetts, one of those ports has been affected by this decision.

One of the projects threatened by the Trump Administration aimed to revitalize New Bedford, Massachusetts, a town once built on the whaling industry. (Photo: Kevin Saff, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

CASH: That's exactly right. I believe that was a $34 million grant where new industries, it was going to attract manufacturing, going to attract service industries, all of the kinds of things that this administration claims that it wants to grow, on shore, domestic manufacturing and commercial industries. And the cessation of these kind of grants is going to have a huge impact.

DOERING: You know, when you were Region One Administrator of the EPA in New England, what did you learn from locals about the promise of wind energy they saw?

CASH: There was a lot of excitement about the possibility of wind energy and what it could bring to their communities. I remember once going to New Bedford, where there was a celebration of all the graduates from a workforce development program that was sponsored by the Environmental Protection Agency. And I met a fellow there who had been in the fishing industry, he had left the fishing industry, was looking for his next way to grow economically. And he found this workshop opportunity where he could be trained as a steel worker and someone who would go out and climb those tall poles where the turbines are and maintain them, and it's a really hard job, and it's a very demanding job, and he loves it. And I just can't imagine what he's going through right now as he's seeing the project that he's working on is a target of the Trump administration. I just don't know what he's talking about at his dinner table right now. It's got to be a tough conversation.

DOERING: And in the case of New Bedford, which offshore wind project was being staged there, and has that been affected by the Trump administration?

President Trump says he wants to increase American energy production. Despite this, he is opposed to offshore wind development. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CASH: Yeah, so there were a number that are out south of Martha's Vineyard. They're in various states of concern about permits being revoked, perhaps stop-orders for them as well. So there's definitely going to be impacts in New Bedford, no question. I think this is a gut punch to the port cities and towns who have been thoughtfully and strategically planning for the growth of an industry that they see can be the next big boost for them. You know, you take a city like New Bedford, and there's something delightfully poetic about New Bedford, because New Bedford, a port town for 250, 300 years, it grew up on whaling. And whaling, you know, it was an industry in the mid 1800s that brought whale oil to ports that then could be distributed for lighting. It was a source of energy. And New Bedford was one of the biggest lighting ports, energy ports, whale oil ports. And of course, as whaling slowed down, that led to economic hardship within New Bedford. And here comes wind on the horizon, offshore wind, that will make New Bedford again a source of light, a source of, this time, electricity that will power the lights in people's homes all over New England. And New Bedford through a very concerted and again strategic effort, through its economic development office, through community groups, through the state's economic development office, through the local community colleges, I mean, the effort was a comprehensive effort that also saw the huge advantage of lifting up members of the community who were struggling economically. And New Bedford has a relatively high unemployment rate compared to other places in New England. And here was a great opportunity to retrain a workforce, and this is the city where I met that former fisherman turned steel worker. And just multiply New Bedford, I don't know, dozen, couple of dozen times, all up and down the East Coast, and all of them are left scratching their heads, why this is happening, as they struggle now to put food on the table. That's one of the many huge negative impacts of this kind of decision-making.

DOERING: David, what are the legal implications of revoking these permits at this stage?

Towns along the New England coast invested in retraining workers to maintain the offshore wind power systems. Now, many of those jobs are at risk. (Photo: Sindugab, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CASH: Yeah, so there's been several litigation efforts that have been made right after the stop-work order for Revolution Wind. Orsted, the European company that's driving this, although it's in partnership with American companies as well, and the states of Connecticut and Rhode Island file suit to stop that. And in the spring, in May, I believe 17 attorneys general had filed a lawsuit against the Trump administration for its one of its first executive orders that also put a target on the back of wind. And so those are cases that are moving forward, it's not totally clear what's going to happen, whether or not the Trump administration can legally reverse some of these permits, is going to be a really interesting question. And I know that there's real concerns about potential violations of the Administrative Procedures Act. You know, this is an act that requires the government to make these kinds of decisions, not in an arbitrary and capricious way. And the argument of these state attorneys general is that the Trump administration has been making these decisions in an arbitrary and capricious way. And so we'll see how that unfolds.

DOERING: Right, like so many things that the Trump administration has been doing, this ends up in the courts, and we'll have to see, I guess, what judges and appellate courts decide ultimately. And maybe even the Supreme Court.

CASH: It might go all the way to the Supreme Court. That's exactly right.

DOERING: So zooming out, what do you think are the bigger legal and economic implications of the federal government revoking these permits, not only to the wind industry itself, but commerce at large?

CASH: I think that the revocation of these permits sends a very, very troubling signal to the private sector, because it says government can change its mind and can be very unpredictable. And that's not what business needs. Business needs certainty. And it needs certainty because business needs investment. And so it goes to an investor and say, hey, I want you to invest in my project here, my projected returns on that investment are so much that you should invest. And if that investor is saying, but wait a minute, you might be 80% done with your project, and the government can stop you. I don't think I'm going to invest in you. That's the real economic concern.

David Cash is the former Administrator of EPA's Region 1, New England. (Photo: Courtesy of David Cash)

DOERING: I think there's been a lot of sense that despite the Trump administration trying to walk back renewable energy, people are reading the tea leaves, you know, a lot of businesses in the United States and around the world think that renewable energy, wind power, solar power, really is the future. To what extent do you think the Trump administration is going to hold back these industries in a way that lasts?

CASH: So let me pose a question to your audience right now. Of new energy projects that began in the last year, let's say in 2024, what percentage of those were renewable energy?

DOERING: You know, I don't, I don't know the answer, David.

CASH: Well over 90%.

DOERING: Wow.

CASH: So renewable energy is not only the future, it's the present, right now. And so, long, long term, we will move into the renewable energy future. But because of what we know about what the science tells us about the climate crisis, we can't afford to wait. But also it's this economic question where we're ceding the opportunity to be global leaders in renewable energy development, deployment and job growth. And we're essentially saying, nah, we don't want to do that. China, you can do that. And India, you can do that. Europe, you can do that. Brazil, you can do that. We're not going to participate in that. And I can't think of another kind of period in history where the writing was on the wall for some kind of new, incredible technology. And a government would say, you know what, we don't want to play in that game. Governments want to play in those because they see huge economic opportunity, and here we're essentially saying we're not going to deal with this now. We'll let other countries take the lead.

DOERING: David Cash is former Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency Region One, New England. Thank you so much, David.

CASH: Thank you. Jenni.

Related links:

- The New York Time "Donald Trump vs. the Wind Power Industry"

- Learn more about President Trump’s claims regarding wind power

- Explore Revolution Wind’s website

- CNBC "Offshore wind has no future in the US under Trump administration, Interior Secretary says"

CURWOOD: And Jenni, by the way, David Cash will be speaking at our environmental justice conference that’s on September 17 and 18! He is part of an all-star EJ cast gathering at the UMass Boston School for the Environment as well as online, and it’s free! You can see Dr. Robert Bullard, often called the father of environmental justice and the Rev. Ben Chavis who brought the disciplines of the civil rights movement to take on toxic dumping in North Carolina.

DOERING: We’ll also have Biden EJ veterans Daniel Blackman and Marcus Hendrix. And don’t miss Goldman Environmental Prize winner and youth activist Nalleli Cobo. All free at UMass Boston on September 17 and 18 or follow online. Just sign up loe.org/events. That’s loe.org/events.

[MUSIC: Howard Roberts, “When The Sun Comes Out” on Good Pickin’s, The Verve Music Group]

DOERING: Coming up, we head to a high school biology classroom for a “tale of two turtles”. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Waverley Street Foundation, working to cultivate a healing planet with community-led programs for better food, healthy farmlands, and smarter building, energy and businesses.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Howard Roberts, “When The Sun Comes Out” on Good Pickin’s, The Verve Music Group]

A Tale of Two Turtles

Pictured above is a painted turtle. Don Lyman initially mistook this painted turtle with a bumpy carapace for a red-eared slider. (Photo: Don Lyman)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

We are back to school and that means Living on Earth’s Don Lyman is back in classrooms teaching biology as a substitute. And before school let out for the summer Don had a teaching moment he calls “A Tale of Two Turtles.”

LYMAN: One morning last year, I walked into a 9th grade biology class for my first substitute teaching assignment of the day and was delighted to see a large, cube-shaped aquarium in the back of the room with a six-inch turtle basking on a platform under a heat lamp. As a biologist and hospital pharmacist who teaches college part-time, I’m always looking for ways to engage my young high school boys in conversation about science. And with herpetology — the study of reptiles and amphibians — being my primary area of interest in biology, turtles work just fine for this purpose.

From the teacher’s desk, the turtle looked like a red-eared slider. Great, I thought, a two-fer – I can talk to the boys about turtles and exotic invasive species. Red-eared sliders are native to parts of the Midwest and South, but not to Massachusetts, where the boys’ prep school I teach at is located. They have been introduced into Massachusetts and other parts of the Northeast, however, most likely having been released by their owners when the cute baby turtles they bought in pet shops grew bigger than expected. Like most exotic invasive species, the concern is that they may outcompete native species or introduce diseases, which could disrupt the ecological balance of their new home.

When I walked to the back of the classroom for a closer look, my initial identification didn’t hold up. The namesake red markings on the side of the head that are characteristic of red-eared sliders were absent. And the carapace — the top part of the turtle’s shell — wasn’t the standard dark green slider color. It was black, with red markings along the lower edges. The color pattern looked more like a painted turtle, but painted turtles have smooth carapaces, and this turtle had a decidedly bumpy slider-like carapace. Could this be a painted turtle with a deformed carapace?

Pictured above is a red eared slider. (Photo: Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Unsure of the species, I gave a brief, tepid turtle talk, and told the class that I had initially thought the turtle was a red-eared slider, but it looked a little like a painted turtle, and now I wasn’t sure what kind of turtle it was. The unidentified turtle stared at me nonchalantly while my reputation as a biologist teetered on the brink of oblivion.

Later in the day, I subbed in another classroom, which also had a large aquarium, but with a 10-inch turtle that was most definitely a red-eared slider. Confident of my species identification, I proceeded to give the mini-lecture I had wanted to give earlier in the day, telling the class a little about red-eared sliders and exotic invasive species.

The next day, I wound up subbing in a freshmen biology class with the mystery turtle once again. I tried to ignore the turtle until one of my students blurted out, “Mr. Lyman, I know you like reptiles. Do you know what kind of turtle that is?” Et tu, Eli? I froze for a second, then told the class about my red-eared slider/painted turtle with a deformed carapace theory. “I’m going to take a picture and send it to some of my turtle friends,” I informed them.

I snapped a photo on my cellphone and texted it to a few of my herpetologist colleagues with my mystery turtle hypothesis. I nervously waited for a reply.

A few minutes later, my cell phone buzzed with a message from Bryan Windmiller, a herpetologist and conservation biologist at Zoo New England in Boston. “Agreed,” he texted. “Looks like a painted, maybe with growth anomalies from being raised in captivity.”

I regained my composure, cleared my throat, ahem, and announced to the class my hypothesis had been validated.

“So, you were right, Mr. Lyman,” one of my young inquisitors said, in a kind of “you lucked out this time” tone.

My herpetological reputation was restored.

The turtle, however, looked unimpressed.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Living on Earth’s Don Lyman.

Related links:

- Learn more about Don Lyman

- Learn more about the painted turtle from iNaturalist

[MUSIC: Cory Wong, The Hornheads, “Click Bait” on The Striped Album, Roundwound Media, LLC]

Huge Danger from Permafrost Loss

The boreal forests of the far north store as much carbon as has been released by human civilization since industrialization. (Photo: USFWSAlaska, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

DOERING: In the far north of our planet, boreal forests and permanently frozen earth, or permafrost, store massive amounts of carbon and keep our global climate in a delicate balance. But with the Arctic warming four times as fast as the rest of the globe, and fires now routinely burning large swaths of northern forests, that locked up carbon is rapidly escaping into the atmosphere where it can warm the planet even faster. Scientists including the late ecologist George Woodwell have been sounding the alarm about this dangerous feedback loop for decades, though for too many in our society, the Arctic is out of sight and out of mind. But indigenous peoples of the Arctic, who are often the first to feel these effects, are raising their voices to spread awareness about their home’s vital role in maintaining a livable world. Edward Alexander is the Senior Arctic Lead at the Woodwell Climate Research Center and a member of the Gwich’in indigenous tribe in Alaska. He’s also a Co-Chair of the Gwich’in Council International, and he joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Edward!

ALEXANDER: Thank you. Thanks for having me, delighted to be here.

DOERING: So tell me a little bit about where you live now and where you grew up. What kinds of climate impacts has your community been facing in the last few years?

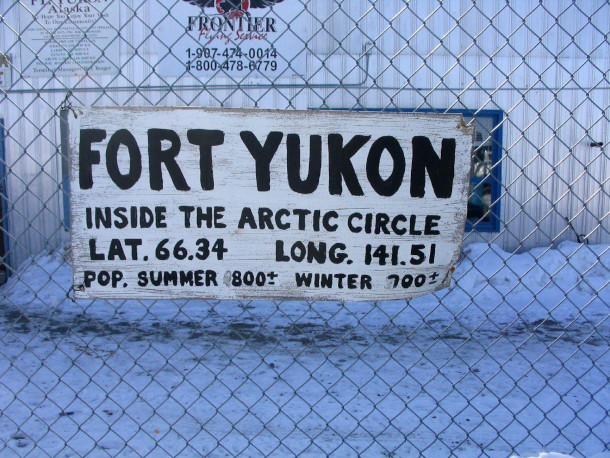

ALEXANDER: So I grew up in a remote, fly-in only community in northeastern Alaska called Fort Yukon. It's eight miles north of the Arctic Circle, and the furthest north the Yukon river goes. It's at the conjunction of the two largest watersheds in Alaska, the Yukon River and the Porcupine. About 65% of the Yukon flats have burned since about 1964, we're talking about an area that's burned equivalent to four Delaware's worth of land just in our immediate neighborhood. Our area has warmed 8.8 degrees Fahrenheit already, just in my lifetime. And so when we think about Arctic amplification, and the Arctic warming four times faster than the global average, you know, this is very pronounced in Gwich'in homelands and the in the Yukon flats in Alaska, the Yukon territories in the Northwest Territories.

DOERING: So we're talking about multiple threats to the Arctic. It's warming four times faster than the planet overall. Then something that's happening is boreal forests are catching on fire. What is a boreal forest?

ALEXANDER: The boreal forest is the largest forest on Earth. It's mostly spruce, with willow and some quaking aspen and some birch. So there's a lot of indigenous communities, not only in Alaska, but also in Canada and in Russia, that depend on this boreal forest for cultural survival, but also just basic existence, finding food and other kinds of things. And so when you think about the boreal forest, which most people don't, we have to think about what it contains. And so it contains as much carbon in the forest as has been released by all human activity since industrialization.

The remote, fly-in only community of Fort Yukon has experienced the impacts of climate change firsthand. (Photo: Kirk Crawford, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

DOERING: Wow.

ALEXANDER: So every car, every plane, every light bulb that's been turned on, right? Yeah, it's an, it's a stunning amount of carbon that's currently stored in this forest. And then it becomes a little more complicated as we go down into the, what's underneath this forest. That's kind of what makes it, even a little more special. The boreal forest has this thick organic layer. And if we think about what's in this organic layer, and why isn't it just releasing this carbon into the atmosphere, is because it's frozen as permafrost underneath the boreal. So this permafrost is very special in that it contains more than twice as much carbon that has ever been released by all human sources, and so people are not aware that it's a frozen foundation that this current society and civilization is built on. People are not aware that every person on Earth depends on permafrost storing vast amounts of carbon, everybody on Earth is dependent on the boreal forest shielding this permafrost from thawing.

DOERING: Yeah, I mean, we sometimes hear permafrost referred to as a carbon bomb because of all the carbon dioxide and methane that it could potentially emit as it thaws.

ALEXANDER: It also releases nitrous oxide, which is 250 times more powerful as a greenhouse gas than carbon. And there's another kind of permafrost that I think probably most of your listeners may not have heard of and that I'm particularly concerned about, that indigenous communities in the north are particularly concerned about, that you know, our folks at Woodwell Climate Research Center are also very concerned about, which is yedoma. And yedoma is a type of ice-rich permafrost, that has a lot of carbon in it, and, you know, has the potential to create huge warming effects for the entire planet, particularly because it thaws as methane, largely, instead of as carbon, like other permafrost.

Permafrost is also a vital carbon store for the planet. When permafrost thaws, it can release greenhouse gases and cause local ground collapse. (Photo: Boris Radosavljevic, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: So not all permafrost is created equally.

ALEXANDER: No, no, yeah, you're kind of run of the mill permafrost is like, we generally consider like one to two meters deep. Yedoma, on the other hand, can go hundreds of meters deep. That's an ancient carbon storage that can be 150-200,000 years old or more. And so it's been there through ice ages and through warm cycles. And so it's seen a lot of fire during the time that it's been on the planet, but in the Yukon flats recently, what we've started to see is that the fire has burned so intensely and so deeply that it's burning off all of the vegetative layer and duff layer above yedoma, and then yedoma is starting to collapse. And something else of particular concern to me is that none of this is included in modeling for climate change, and so the wildland fire crisis across the circumpolar is still considered like a stable ecosystem by climate researchers generally, and permafrost is considered a stable system, and it's important that we understand that there are changes happening here. The Yukon flats is very indicative of that, which is why the United States Fish and Wildlife Service has moved to protect yedoma as a value at risk in the region. A yedoma deposit thawing could be more emissions than small countries, or even, you know, if all of the yedoma thaws, it'd be more, more emissions than all of the countries.

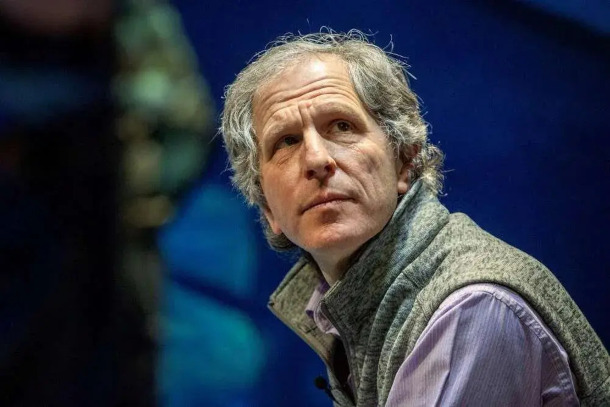

Edward Alexander speaks at COP29 in Azerbaijan in 2024. (Photo: Pavel Sabudzinsky / Hi Impact)

DOERING: And what exactly is happening here with climate? I mean, I understand that there's so much warming happening in the Arctic, so what is it in that process that, in that warming, that leads to this permafrost thaw?

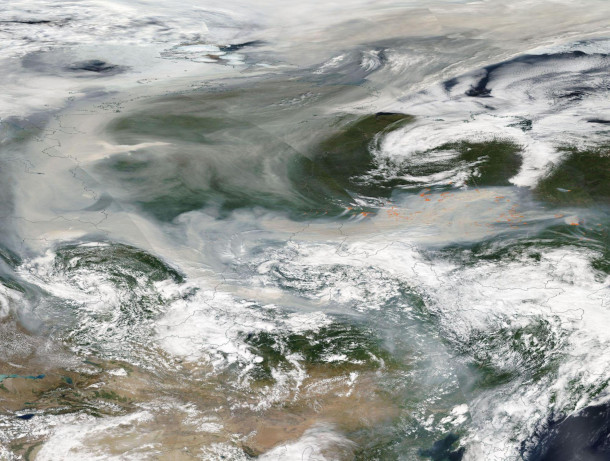

ALEXANDER: Well, I think one of the things, well, you have the average air temperature being a lot higher. The main driver that I've been concerned about for a while is the impact that wildland fire has on permafrost thaw and on yedoma thaw, particularly. Most people don't think about wildland fires in the Arctic until there's smoke blowing into New York City or into Boston or into DC, and so they experience it as a smoke event. The other side from where that smoke is originating, the emissions are huge, right? And then you think about, what are the after-effects? What's the post-fire world look like in the Arctic? And so what happens is, this layer of vegetation gets burned off, and we're seeing it burn more deeply than ever, and it burns down into this duff layer, which is like an organic mat that is on the forest floor and so forth. And the problem with a duff layer burning is that it's the insulation, essentially, that keeps permafrost frozen, so if you have imagine your cooler, and you're out there and you've got, like, your frozen stuff or your cooled stuff, and you take the cooler lid off, and then everything inside starts to spoil, and that's essentially what's going on with permafrost. And so you have these areas where a fire can come in and burn off all of this insulation, a huge fire, because fires in the Arctic have gotten to be massive. And then year two, year three, year four, year five, of that fire, there's still emissions occurring from those fires. At that point, it's not a flame, but you're seeing permafrost thaw, subsidence, ground collapse. You're seeing areas where there's large like landslides into rivers, affecting water quality, affecting fish in those rivers. And that's really this kind of intersection of where wildland fire has this profound impact over vast areas of land, and then it has this secondary effect of having, generating this opportunity for permafrost to thaw, and that's an opportunity that we want to prevent.

Intensifying wildfires in Arctic boreal forests threaten these crucial carbon stores on the planet. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, MODIS Land Rapid Response Team, NASA GSFC, Public domain)

DOERING: You know, what are some things we can do that might help here? I mean, are there indigenous practices that can help with wildfire management? And this connected issue of the permafrost thawing?

ALEXANDER: You know, we've seen 174 million hectares burn across the circumpolar boreal. 174 million acres is equivalent to the entire state of Oregon burning and then also the entire state of California and Nevada and Utah and New Mexico and Arizona all combined. When we think about this problem, it's not a chainsaw problem, it's not an ax problem. It's not like you can just get a bunch of men and women out in the field and cut fire line and have like, this problem be solved. And the kind of interventions that we've normally had for a wildland fire in the south, like digging a trench, if you dig a trench to stop a fire in California, that's an effective solution there. In the north, and in the Arctic, if you make the same kind of fire line, you can create a long lake because you're removing the surface layer of insulation, essentially from that land. So we have to be really thoughtful about it. And I think one of the things that is really promising to manage wildland fire across the Arctic is using cultural practices of indigenous peoples across the circumpolar north. One such practice is Gwich'in cultural burning, Gwich'in cultural fire, practiced early in the spring, and as spring comes around, the areas that melt first are these meadows and lake edges. This area becomes uncovered with snow from the heat of the sun in the springtime, but there's still snow in the forest. And so traditionally, our people would go out and burn these meadows and burn these lake edges. It helps to, increase the forage capacity of the land, so the plants that come back are much more nutritious for all the animals. And so that's very important for people who depend on these animals to survive too, right? And so that's traditionally why Gwich'in did these practices. But in the modern context, it creates a fire break. So in the summertime, if you have a fire burning through the forest, and then it comes across an area that's already burned in the spring, it's not going to burn twice, right? You've already burnt off all of the dry fuel in that area. The other reason why it's an important intervention is that when we think about protecting the carbon in that soil, this practice is done early in the spring when the ground is still frozen, and so you're protecting all of the carbon in the soil, all the carbohydrates and the roots from the plants that have stored all winter. So as far as limiting fire extent, limiting fire severity, so preventing these fires from burning down into some of these deeper peaty areas, exposing the areas beneath it to permafrost thaw or yedoma thaw, even more worrisome, and so part of it is Gwich'in indigenous practices from other places typically promote mild fire instead of wildfire.

Edward Alexander is the Senior Arctic Lead at the Woodwell Climate Research Center and a member of the Gwich'in indigenous tribe in Alaska. He is also a Co-Chair of the Gwich'in Council International. (Photo: Eric Lee)

DOERING: You know, Edward, it sounds really challenging to live in your home right now, as the climate crisis accelerates and causes all of this damage to the land, to the planet as a whole. What gives you hope and what keeps you committed to fighting such a tough fight?

ALEXANDER: Well, I think that the alternative is not something that I'm willing to concede. You know, for people in the Arctic, we've dealt with profound change on an order of magnitude that other people across the world have not had to reckon with yet. And I think part of it is, in order to have some of the hope that I have and optimism I have is, I decenter humans from the discussion a little bit too, like it's not just about us. People always say, well, we do this for our children in the future. That's true. I have children and I care about their future. I also care about the animals and their futures. I also care about the plants and their futures, right? And we can work together. Not fight, not fight the issue. That's a real, it's like a western idea. We're gonna have a battle. We're gonna fight this thing.

DOERING: Yeah.

ALEXANDER: Well, no, don't, no. I'm from a small indigenous community, and guess what? You learn in that community is you've got to work together. And if we understand that we got to work together, we got to be kind on this issue, we're going to get there. We will fix these problems.

DOERING: Edward Alexander is the Senior Arctic Lead at the Woodwell Climate Research Center. Thank you so much, Edward.

ALEXANDER: Thank you for having me, delightful to be here.

Related links:

- Read more about Edward Alexander’s work at the Woodwell Climate Research Center

- Learn more about the Gwich’in people

- Woodwell Climate Research Center | “Cultural Burning: The Important Role of Traditional Practices in the Modern Arctic”

[MUSIC: Tony Furtado, “Squirrelville” single, Anthony Furtado]

CURWOOD: After the break, searching for peace and quiet amid the “clamor” that fills our modern world. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the estate of Rosamund Stone Zander - celebrated painter, environmentalist, and author of The Art of Possibility – who inspired others to see the profound interconnectedness of all living things, and to act with courage and creativity on behalf of our planet. Support also comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Julian Lage, “Nothing Happens Here” single, UMG Recordings]

BirdNote®: The Auspicious Chime of the Bare-throated Bellbird

The bell-throated bellbird pictured above is native to Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina. (Photo: INaturalist, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

DOERING: In a moment, we’ll talk about the human-made noise in our world and how we can reclaim some peace amid the clamor. But first this BirdNote from Nick Bayard about a bird with some serious pipes!

BirdNote®

The Auspicious Chime of the Bare-throated Bellbird

Written by Nick Bayard

This…

[Bare-throated Bellbird Call, ML604636271]

…is the exceptionally loud, metallic call of the Bare-throated Bellbird. It’s so loud that it can be heard nearly a mile away. Let’s hear it again.

[Bare-throated Bellbird Call, ML604636271]

The Bare-throated Bellbird is the national bird of Paraguay. Males are covered from nearly head to tail in striking white plumage, but the area around their beaks and extending down across their throats is, well, bare — exposing teal-colored skin.

[Calls of multiple Bare-throated Bellbirds, ML362636901]

Females blend seamlessly into the foliage with olive green backs and flecks of yellow across their breasts. The Bare-throated Bellbird is considered a key indicator species, so hearing its loud chime suggests that you are in a healthy and functioning ecosystem.

In the indigenous language Guaraní, the Bare-throated Bellbird is known as Guyra pong, with “Guyra” meaning “bird,” and “pong” referring to…

[Bare-throated Bellbird Call, ML604636271]

A Bare-throated Bellbird in Paraná, Brazil. (Photo: Ben Tavener, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

Beloved in Paraguay for its call and its beauty, the Bare-throated Bellbird inspires music played on another emblem of Paraguay — the harp. Here is the song, Pájaro Campana, Spanish for Bare-throated Bellbird, played on the Paraguayan harp.

[Clip of Pájaro Campana, performed by Ann Brela y Sus Cuerdas]

I’m Nick Bayard.

###

Senior Producer: Mark Bramhill

Producer: Sam Johnson

Managing Editor: Jazzi Johnson

Content Director: Jonese Franklin

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Bare-throated Bellbird Call ML604636271 recorded by Andy Bowen, calls of multiple Bare-throated Bellbirds ML362636901 recorded by Henry Miller Alexandre. Clip of Pájaro Campana, performed by Ann Brela y Sus Cuerdas.

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2025 BirdNote March 2025

Narrator: Nick Bayard

ID# BTBB-01-2025-03-17 BTBB-01

DOERING: For pictures, flap on over to the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related link:

BirdNote® | “The Auspicious Chime of the Bare-throated Bellbird”

The Health Risks of Noise

Chris Berdik’s latest book, Clamor: How Noise Took Over the World and How We Can Take It Back. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Berdik).

CURWOOD: There’s one environmental pollutant at large that most of us encounter day and night, yet it’s rarely discussed.

[montage of cars honking… engines revving… construction… siren… leafblower – all sounds from freesound.org]

CURWOOD: Noise.

It’s bad for our health, disrupts our natural world, and hinders our ability to connect with one another. In his recent book, Clamor: How Noise Took Over the World and How We Can Take It Back, author and journalist Chris Berdik explores the hidden costs of unwanted sound and advocates for turning down the volume on human-made noise. Once upon a time, Chris Berdik was a Living on Earth intern and he joins me now. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Chris!

BERDIK: Thank you so much, Steve, great to see you again.

CURWOOD: So this may be a silly question, Chris, but why should we care about noise?

BERDIK: It's not a silly question. I think people care deeply about noise when it's in their ears, when it's 3am and there's a car alarm going off down the street, when they're trying to finish a deadline at work and all they can hear is the chatter of their office mates, when they're visiting a loved one in the hospital who hasn't been able to sleep in several days because of all the alarms. When that happens, people care extremely deeply about noise. My argument is that they should care about noise as a systemic problem because of all of the sort of widespread impacts that it has, the harms that it has on our health and our well-being, the degrading of our natural habitats. To care about these things is to care about noise.

CURWOOD: One of the theses of your book is that our understanding of noise is oversimplified by simply measuring how loud it is, that is, measured in decibels. Talk to me about that. What is the decibel and why is it an overly simplistic way to look at noise?

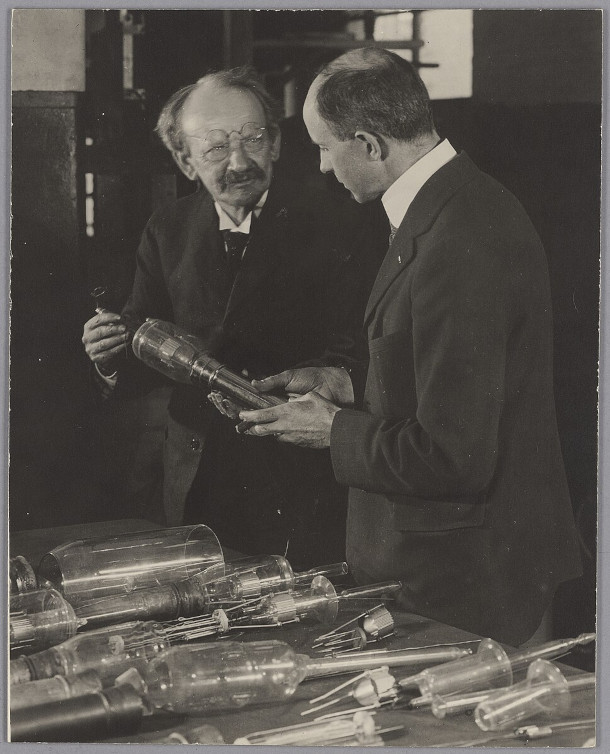

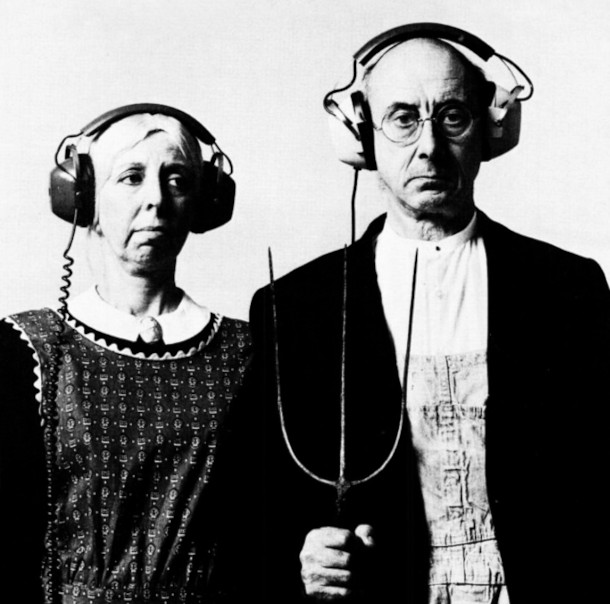

Sound is typically measured in decibels, a metric coined by the Bell Telephone Laboratories in the 1920s. Above, a 1923 photo of Professor of Experimental Physics, Joseph J. Thomson (left), and President of Bell Labs, Frank B. Jewett. (Photo: MIT Museum, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BERDIK: The decibel is a metric that was devised by Bell Labs in the 1920s, and what it measures is the acoustic sound intensity. The full measurement of it is watts per meter squared. And they created the decibel scale as kind of a simplified way of covering the vast amount of acoustic energy intensity that spans the range of human hearing. But all it is is this sliver of what we would interpret as loudness of the sound. It became a go-to measurement because it was so simple, it was very easy to think about it as the dividing line between wanted or unwanted sound based on how loud it was. But what it ignores is everything else about the sound, part of it being the acoustic measurements of rhythm, of tonality. But more than that, the context in which we're listening to different sounds, and those are vitally important. It really matters when you're listening to certain sounds, whether you are trying to sleep, or whether you are trying to socialize, or whether you are on a hike in a woodsy park, or you are in your hospital bed, these are all different contexts that have a much bigger impact on whether sound is wanted or unwanted than just how many decibels it is.

CURWOOD: Chris, tell me, how does noise affect our interactions with each other?

BERDIK: Well, basically, our hearing is our way of connecting with one another, and when we start to lose that ability, for instance, in a crowded restaurant, then sometimes what will happen is people will just stop trying. People will sit there and just eat their food, nod along when other people are talking, or they will stop accepting the invitations to socialize with one another. There's research out of Johns Hopkins showing that people who have hearing loss have a much higher risk of depression and dementia, and the potential reason for that is because they are withdrawing socially, because they have difficulty in connecting because of the hearing loss.

In the modern day, a noisy restaurant can make it hard for conversations to be heard. This can be increased especially for those who are deaf or hard of hearing. (Photo: Darya Sannikova, Pexels, Pexels license)

CURWOOD: So we may not think of it as one, but noise is an environmental pollutant, as you say, affects our health, say, as much as having lead in the water or particulate matter in the air. Talk to me more about those impacts on our health.

BERDIK: Sure, well, the first part of it is the impacts on our, our hearing health. The WHO, the World Health Organization estimates that by 2050, about 2.5 billion people on the planet will have hearing loss, which is a combination of aging and noise-induced hearing loss. They also estimate that young people, about a billion of them, are at risk of noise-induced hearing loss just by listening to their devices too loudly. The other part of the health impacts are less reliant on decibels. They are more reliant on how unwanted sound can cause us chronic stress and can disrupt our sleep. And these impacts, along with other things that can cause us chronic stress, start to have these cascading health impacts, clogging our arteries, increasing the amount of cortisol pumping through our bodies. All of these downstream impacts are because we are exposed to sounds that are getting in our way of being able to focus, getting in our way when we're trying to communicate, and waking us up at night, even when we're not fully aware of how much disruption they're causing. They are keeping us from having that restful state that comes along with sleep, when our heart rate goes down, our blood pressure goes down, but our ears are still attuned to the world because they are kind of trying to keep us safe, and when they hear sounds and noise from, say, traffic, they will cause our blood pressure to go up and our heart rates to go back up, and we will feel the effects of those if that happens in a chronic way.

CURWOOD: So you dedicate a chapter of your book to what's called the noise gap, or disproportionate effects of noise on certain populations. Please explain to me what those are.

The World Health Organization estimates that 2.5 billion people will have hearing loss by 2050. Berdik adds that young people are especially at risk due to listening to their devices too loudly. (Photo: RCA Records, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BERDIK: So the noise gap, the first use of that term was from a 2017 study that took a macro look at this, which was they looked at census tracks nationwide, and they had modeled noise exposure from transportation, from road, from rail, from airplanes. And they saw that as these census tracts became more affluent and whiter in their population, that they had fewer decibels of exposure to this noise. And so subsequently, it had been followed up by a number of city-by-city studies looking at neighborhoods that had been redlined in the 30s and 40s, which was a biased way of determining the risk for investors that was largely based on the ethnic and racial makeup of different neighborhoods in different cities. And what these studies find is that formerly redlined neighborhoods have more noise exposure in addition to other pollution exposure, and they also have less green space, so they have not as much buffering to that city sound.

CURWOOD: Now when we talk about the varying effects of noise on different populations, we can't forget about the most vulnerable among us. That's the natural world. They don't get to have a hand or a paw or a fin on the volume control. How are our non-human counterparts uniquely affected by disruptive sounds?

BERDIK: Yeah, well, you had it just right there. They can't put a paw on the volume control knob. They also can't put a pair of noise-canceling headphones on when they are bothered by sound, they rely on being able to hear in order to connect with one another, to find mates, to forage for food, avoid predators, you name it, hearing is incredibly important to wildlife. Looking at wildlife in the ocean, oftentimes, you know, they have to communicate over vast distances in low light, where you know, seeing is not the best option. Hearing is incredibly important. And when you have human noise coming into these environments, especially the kind of noise that is constant, that never goes away, in the ocean that's principally from ocean-going vessels, cargo vessels, tankers. It creates what some conservationists have called a "sensory smog" that shrinks the sensory world of these animals. Makes it that much harder for them to find food, to escape predators, to talk to one another. It's what Leila Hatch, who's a marine biologist, has called a stress multiplier. And many of these species have quite a lot of stresses that they're already dealing with, and they don't have a lot of reserve energy in order to deal with them.

CURWOOD: That's interesting, because we've seen off the coast of Spain, orcas, or like so-called killer whales, sometimes going after sailboats, kind of attacking them. Makes me wonder if they're irritated by the noise that they hear.

Aquatic ecosystems are especially vulnerable to human noise disruption because they rely on sound to hunt, mate, and communicate in the dark ocean. (Photo: Robert Pittman, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BERDIK: Yeah, that could be. I think there's just so much that we don't know about the sonic worlds of creatures who are not us. This is a concept called umwelts, which was coined by a German biologist in the 1800s named Johann Jakob von Uexküll. And it was just this idea that animals don't experience sound or any of the other senses in the way that we do. There could be a number of sounds that bother us intensely that a certain species can't hear at all, that sound may be important for them at certain points, but easily ignored by them otherwise. And the amount of research that's been done has mainly been looking at, you know, a bit of potential hearing loss among animals, which can be a problem, especially for mammals, but not as much for other animals, which are able to regrow parts of their inner ear and hearing system, and also sort of behaviorally. What do they do when noise is present, when a ship is passing by? Are they less efficient at hunting, do they have louder vocalizations, that sort of thing? But we haven't, we've just barely scratched the surface to understand what their sensory worlds are and how they would react to specific sounds.

CURWOOD: How is our changing environment, and specifically climate disruption, intensifying the noise crisis do you think?

BERDIK: Well, one big way is that the Arctic ice used to be a protector of quiet, because you couldn't have ships going over it. You were limited in your ability to do other noise-producing things like explore for gas and oil and do the natural resource extraction. As that ice melts, we're seeing a fast uptick in the vessel traffic there, and more interest in exploring those areas for resources. So that is going to quickly eliminate one of the last quiet refuges, and that's one way. Another way is that this changing climate, it's increasing the need for animals to go far afield to find their food. The plankton that certain whales need to eat many, many tons of every day is, they're shifting in where they can be found because of the changing climate. So the whales have to go and go further to find these food sources. At the very same time that their sensory world, their ability to do that kind of an exploration, is shrinking due to the noise. So it's, as Leila Hatch said, it's a stress multiplier that you have the need for animals to have a larger world at the very time that their sensory world is shrinking.

Chris Berdik is an author and journalist whose work covers the intersection of science, health, technology, and education. (Photo: Courtesy of Chris Berdik)

CURWOOD: Chris, I mean, to what extent is all noise bad? I mean, is there anything we can do not to just decrease harmful noise, but incorporate better sounds into our daily lives?

BERDIK: Yeah, all noise is not bad. There are many noises, many sounds that have shown to be a benefit to us. In particular, the sound of nature. This has been shown to lower our cortisol levels, to lower our heart rates, to help restore our attentional resources. You know, part of this is just being cognizant of it and taking the time to get out into green spaces and spend time in wilderness areas when we're able to. That, of course, means protecting those soundscapes and understanding that when we are trying to keep the sensory smog of human noise out of wilderness areas that we're, we're not just doing it for the wild creatures, but we're doing it in some sense for ourselves as well. When we neglect sound and the sonic environment, that can do us quite a bit of harm, and when we pay attention to it, it can actually be an ally and a resource for us.

CURWOOD: Chris Berdik is the author of Clamor: How Noise Took Over The World -- and How We Can Take It Back. Thanks for joining us today, Chris.

BERDIK: Thank you so much, Steve, it's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Learn more about Chris Berdik

- Purchase Clamor: How Noise Took Over the World and How We Can Take It Back and support both Living on Earth and independent bookstores

[MUSIC: Voyageur “Before the Sun” on Canyonlands, Voyageur]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Daniela Fariah, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio, and we always welcome your feedback at comments@loe.org. And remember to sign up for our environmental justice conference on September 17 and 18, in Boston and online. Just sign up at loe.org/events. That’s loe.org/events. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth