PFAS and Our Genes

Air Date: Week of October 17, 2025

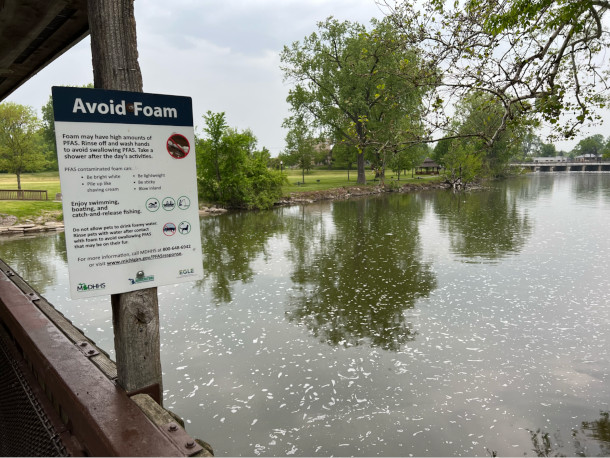

PFAS are commonly found in water repellant materials, firefighting foams and are also used in industrial food production. While PFAS are not intentionally added to food or water, they can accidentally leak into the environment, contaminating both. (Photo: MountainFae, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

A recent study found that exposure to certain PFAS chemicals, which are pervasive and persistent in the environment and human bodies, can lead to changes in gene expression that are linked to cancers, autoimmune and other immune disorders, and neurological disorders. Lead researcher Dr. Melissa Furlong from the University of Arizona speaks with Host Steve Curwood about the findings.

Transcript

CURWOOD: In late October the European Union will begin to phase out the widespread use of PFAS in firefighting foam, with the restriction approved by both the European Parliament and Council. PFAS are a class of toxic chemicals linked to cancer, immune system suppression, liver and kidney damage and developmental issues in children. They are found in many everyday products, from nonstick pans to water repellant clothing, and their resistance to heat, oil and water makes them a popular and widespread ingredient in firefighting foam. PFAS are very persistent in the environment, especially in ground water, and even small exposures can accumulate in our bodies. A recent study published in the Journal of Environmental Research that sampled firefighters found that exposure to certain PFAS can lead to changes in gene expression. To help us understand how these chemicals can harm us, we’re joined today by lead researcher Dr. Melissa Furlong from the University of Arizona. Dr. Furlong, welcome to Living on Earth!

FURLONG: Thanks Steve, happy to be here.

CURWOOD: So tell me what got you into this research, what prompted you to do this kind of study?

FURLONG: So, right after I graduated from college, I worked at a legal aid office, and part of that job was to do outreach to farm workers to educate them about their legal rights, and we also worked closely with people who would educate farm workers about their pesticide exposures. I, at the time, thought that all chemicals were regulated by the federal government, and that chemicals that were used in the environment were regulated for safety. That year, I was disabused of that notion.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I was gonna say, surprise!

FURLONG: Surprise, yeah, but I learned that a lot of these chemicals, well, particularly pesticides, are designed for toxicity, and just because they are designed for toxicity in insects does not mean that they are safe for humans. And this is because a lot of the targets in insects are actually present in humans, and from there, it was just a slippery slope into learning about all the other chemicals that humans are exposed to that are not necessarily regulated adequately for safety. Recently, I have been interested in working with firefighters, because firefighters are exposed to lots of different environmental chemicals in their service, and the firefighters are particularly concerned about a class of chemicals called PFAS, which stands for per- and polyfluorinated, alkylated substances, and they have slightly higher exposures than the general public.

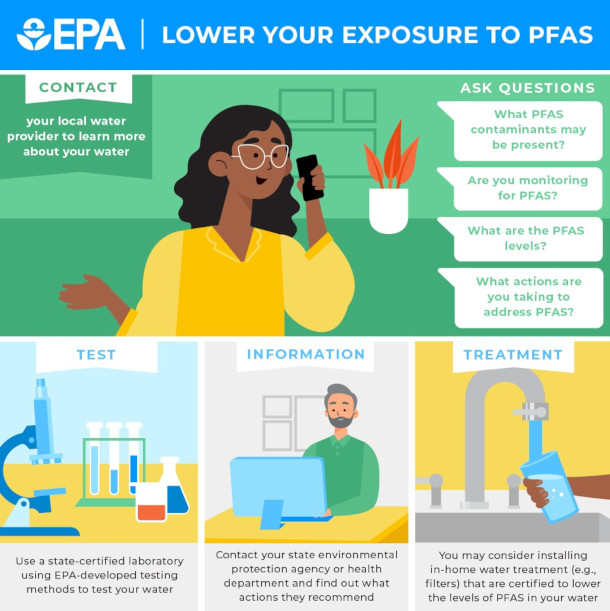

EPA Infographic, "Lower Your Exposure to PFAS." with guidance on ways to decrease individual exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in drinking water. Recommendations include testing your water and installing appropriate water treatment systems. (Photo: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C., Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

CURWOOD: So, the term forever chemicals is often used when describing these fluorinated compounds, PFOAs, and PFAS. How accurate is this term?

FURLONG: Yeah, so we call them forever chemicals because they last a lot longer in the environment than a lot of other modern-use chemicals. They stick around for a few years, up to decades, and that's the same in the body too. There were chemicals that were around a long time ago, that had half-lives of like hundreds of years, if you remember DDT or some of the other organochlorine pesticides, or PCBs, many of those were banned in the 70s, but the half-lives on those were hundreds of years, and we're still exposed to those. So those are the sort of true forever chemicals. PFAS are kind of like modern forever chemicals.

CURWOOD: Now what's the concern about exposure? It could be in a non-stick pan or in a waterproof jacket. What about water and food itself? What risk do we face from PFAS there?

FURLONG: The public is predominantly exposed to PFAS through our water and through contaminated food. It's not intentionally in our food or our water supply, it has just leached into those things because of industrial uses. And close to 100% of people have detectable levels of at least some different types of PFAS species.

CURWOOD: Your study is very exciting because you look at something called microRNA to look at something known as gene expression. Now, for the non-scientists among us, could you explain what microRNA is and how it differs from DNA and messenger RNA—mRNA, and, of course, the whole phenomenon of gene expression?

PFAs, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are human-made chemicals known for their persistence in the environment, sometimes being referred to as “forever chemicals” because they do not break down easily. These substances are not biodegradable and resist degradation by water, heat, or sunlight. Their widespread use and environmental persistence have raised concerns about potential health impacts and environmental contamination. (Photo: Mplanine, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

FURLONG: Sure. So hopefully, everybody is familiar with the concept of DNA, right? Everybody's born with your DNA. Those are your genes. We have a copy of our DNA in every single cell. And the way that the DNA gets turned into who we are, into humans, is the DNA has to get translated into a protein. Part of that process is called DNA expression. So the way that your DNA is expressed eventually makes you who you are, and that is a little bit of a complicated process. So the way that the body turns different parts of our DNA into proteins is through RNA. What messenger RNA does is it copies the relevant section of the DNA, and then that mRNA goes and it eventually turns into some proteins. The microRNA attaches to the messenger RNA. So, sort of on that path between DNA and protein, microRNA changes the way that the genes are expressed, essentially. So an analogy that we like to use sometimes is, let's imagine that the piano is your DNA. The keys don't change, right? But the music that you play, the sheet music that you play, changes the way the piano sounds. And so the sheet music is the expression of the piano, and the sheet music itself can also be changed by the human that is playing the piano. Right? Each person who plays a musical score might sound a little bit different from each other.

CURWOOD: And that individual difference is what the messenger RNA, and indeed, the microRNA can apply to this process.

FURLONG: Right.

CURWOOD: So, your study focuses on changes in gene expression due to exposure to PFAS. Can you clarify the difference between a change in gene expression and a genetic mutation?

PFAs can contaminate bodies of water and accumulate in the form of foam that behaves similarly to shaving cream. State guidance might notify visitors to prevent people and pets from consuming water from the area. (Photo: MountainFae, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

FURLONG: Yeah, sure. So, a mutation is an actual change in the genome itself. So if we're thinking about a piano like maybe one of your keys is broken or that key doesn't exist, or is out of tune, it sounds wrong. But a change in the gene expression doesn't actually mean there's anything wrong with the underlying DNA. Your underlying DNA can be fully intact. It's just the way that it's translated or transcripted or expressed that is changed.

CURWOOD: So based on your findings, what specific biological pathways or processes does PFAS exposure appear to be disrupting?

FURLONG: Yeah. So, unfortunately, there appeared to be lots of pathways that were affected. We looked at nine different PFAS, and about four of them seemed to be really strongly associated with several different pathways. And basically it came out into three buckets, which were cancers, autoimmune and other immune disorders, and neurological disorders.

CURWOOD: To what extent does our chemical regulatory framework pay attention to how genes are expressed and affected by chemicals?

FURLONG: That's a really good question. So epigenetics is basically the way that our DNA is expressed, and is fairly new in terms of the study of how environmental chemicals affect health outcomes. So we can see these changes in gene expression that are linked to kidney cancer, but it's not proof that exposure to this particular PFAS is definitely going to end up in kidney cancer. So, I don't think that the regulatory framework has been able to incorporate some of these signals quite as readily as they can consider things like a direct association. So it's not an easy thing necessarily to be incorporated into the regulatory framework. The advantage of this kind of study is that, because it's untargeted, we can look at all of these diseases at once. So if we were to look at, you know, every autoimmune disorder, every cancer, every neurological disorder, in a separate study, that would be 10s of millions, possibly hundreds of millions of dollars, right? So we can look to see what's popping up in this untargeted study, and then we can do more targeted looks at some of these specific health outcomes, and hopefully that will eventually turn into stronger evidence that can be used for regulatory purposes.

CURWOOD: Your research focused on firefighters. To what extent do you expect to find similar patterns of disruption of, of genetic expression in the general public from the effects of PFAS?

FURLONG: So we know that firefighters have slightly higher levels of some of the PFAS, but we would assume the dose-response relationship would be the same, even at lower levels of PFAS, and most of the firefighters’ exposure is through the same routes as the general population. They just have some of these additional routes of exposure for some of the specific PFAS, but for the health effects, you know, the way that a PFAS changes gene expression in firefighters should mechanistically be the same as the way it changes gene expression in other people—in the general population.

CURWOOD: So, how concerned do you think the average person should be about their personal exposure to PFAS? I mean, beyond some broad regulatory changes, perhaps, what actionable step might an individual take to reduce the load of PFAS in their daily life?

FURLONG: Yeah, so some people developed pretty severe anxiety about our environmental chemicals, and I understand, because I went through this phase, you know, 10 years ago, when I was first starting this research. But you know, anxiety and stress itself can have some pretty negative health consequences, and the truth is that unless you are highly exposed or genetically sensitive, you are better off worrying about more general health positive behaviors like getting regular exercise and eating a diet that's high in fruits and vegetables and other fibers. However, there are still some relatively easy steps that you can take to reduce your PFAS exposure. So some of those would include using a water filter. A lot of the municipal water supplies, like from your local city, are now trying to treat for PFAS to keep it under certain levels, but you can still install a water filter in your home or use a Brita if a more sophisticated filtration system is out of reach. It's very important to maintain your filters regularly. There's some evidence that your exposures might be higher if you don't change your filters often. And then reducing your consumption of ultra processed foods will also reduce your PFAS exposure and generally be healthier for you. You can also try not to use your non-stick pans. I know it's really hard when you're making scrambled eggs, but if you get a well-seasoned cast iron pan it works just as well, and they're not that expensive. So those are the big ones.

CURWOOD: Melissa Furlong is an environmental epidemiologist at the University of Arizona in Tucson, Arizona. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

FURLONG: Thank you so much, Steve. It was fun talking.

Links

Innovation News Network Europe Cracks Down on PFAS in firefighting foams with new restrictions

Learn more about environmental epidemiologist Melissa Furlong

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth