October 17, 2025

Air Date: October 17, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Coalition Defends Solar for All

View the page for this story

Facing lost jobs and higher energy prices after the Trump EPA canceled $7 billion in low-income solar grants, a coalition of labor, green and anti-poverty groups is teaming up to fight in court for clean energy jobs and save “Solar for All.” Patrick Crowley, President of the Rhode Island AFL-CIO, and Kate Sinding Daly, Senior Vice President for Law and Policy at the Conservation Law Foundation, join Host Steve Curwood to explain the impact of the canceled grants and the legal basis for their lawsuit. (14:50)

BirdNote®: Melanin Makes Feathers Stronger

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Birds as different as gulls, pelicans, storks, and flamingos all have black-tipped wings. These flight feathers are rich in a pigment called melanin. BirdNote®’s Michael Stein reports that melanin doesn’t just provide color – it also helps make feathers stronger. (01:53)

PFAS and Our Genes

View the page for this story

A recent study found that exposure to certain PFAS chemicals, which are pervasive and persistent in the environment and human bodies, can lead to changes in gene expression that are linked to cancers, autoimmune and other immune disorders, and neurological disorders. Lead researcher Dr. Melissa Furlong from the University of Arizona speaks with Host Steve Curwood about the findings. (11:22)

Taming the Monsters of Halloween Waste

View the page for this story

One of the most frightening aspects of Halloween is the monstrous amounts of waste it can generate. Katie Brewer of Greater Laingsburg Recyclers in Michigan joins Host Jenni Doering to share ideas for making Halloween a little more sustainable, from recycling candy wrappers, to composting pumpkins, to thrifting costumes. (06:59)

Chicago River Restored to Health

View the page for this story

On September 21st, hundreds of people leapt into the Chicago River for the first public swimming event since 1927. Friends of the Chicago River Executive Director Margaret Frisbie joined Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill to discuss how major projects including green infrastructure have helped clean up the river for both people and wildlife to enjoy. (10:08)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

251017 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Katie Brewer, Patrick Crowley, Kate Daly, Margaret Frisbie, Melissa Furlong

REPORTERS: Michael Stein

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Trump’s EPA cancels low-income solar grants.

CROWLEY: 900,000 American households have lost the opportunity to put up affordable solar. It’s poor people across the entire country that wanted to do the right thing but didn’t have the access to financing. All of that is gone up in smoke right now.

DOERING: Labor, green and anti-poverty groups are teaming up to fight for clean energy.

CURWOOD: Also, the Chicago River hosts its first public swim day in almost a century.

FRISBIE: Seeing hundreds of people in the water swimming so joyfully really represented all the work that Friends of the Chicago River and so many organizations and agencies have done to improve the health of the river, not only for people, but for wildlife too.

CURWOOD: Plus, tips for a more sustainable Halloween. All that and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Coalition Defends Solar for All

The $7 billion Solar for All Program, implemented by the Biden administration, was created to increase access to solar energy for low-income households and communities across the United States. (Photo: Montgomery County Planning Commission, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I'm Steve Curwood.

In May when the Trump EPA canceled a $20 million grant to the remote Alaskan village of Kipnuk, the town sued, saying the funds were "essential to prevent environmental and cultural catastrophe." But on October 12, before the courts had acted, catastrophe struck Kipnuk as erosion and melting permafrost linked to climate change led to massive and fatal flooding from the remnants of a typhoon in Asia. This is just one of more than 600 climate grants for disadvantaged communities canceled so far by the Trump White House, including the $7 billion Solar for All program. Facing lost jobs and economic disaster, a coalition of unions, antipoverty and green groups led by the Rhode Island AFL-CIO went to court to fight back.

CURWOOD: On the line now from Cranston, Rhode Island, is Patrick Crowley. He's the President of the Rhode Island AFL-CIO, a federation of labor unions in the state. Welcome to Living on Earth, Patrick!

CROWLEY: Thank you, Steve. It's a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: So tell me, what was the Solar for All program? What kinds of projects and programs was this money going to fund?

CROWLEY: Solar for All was a unique program that was initiated under the Biden administration that would have provided solar power to disadvantaged communities, and in a place like Rhode Island, it would have been hundreds, if not thousands, of homeowners were going to be able to put solar on their houses without having to negotiate some pretty steep upfront costs. We would have gotten $49.3 million out of a $7 billion total package, and it was going to put hundreds of my members to work, but also it was going to reduce the cost of electricity across the entire state of Rhode Island. Rhode Island does not produce any of its own electricity. We have to import it all. So by having a Solar for All program, we would have had access to some really good, cheap, reliable power.

CURWOOD: So what are the economic consequences then, of canceling this funding, both in your state and in the United States?

Rhode Island imports all of its electricity. (Photo: Dennis Weeks, Flickr, CC BY 4.0)

CROWLEY: Well, the immediate consequence is we're going to see electricity bills continue to rise. You know, by not having that solar program in place, it's going to mean that we're going to get our electricity from legacy fossil fuel developers, all of which are subject to extreme market fluctuations, depending on what's going on on Wall Street or what's going on in international affairs. So that's problem number one. Problem number two is thousands of job opportunities just evaporated overnight. And one of the things, Steve, that we talk about here in Rhode Island, Rhode Island is a blue-collar, working-class labor state, but the average age of a construction worker is 55 years old in our communities, and the new generation of construction workers don't look like the guys that are there now. They're brown, black and female, and what the Solar for All program was going to do was require the utilization of apprentices, which meant that we were going to also train the next generation of construction workers while we were creating new jobs and saving money for homeowners.

CURWOOD: So if you step back from Rhode Island for a moment, how big a deal is this for the United States, do you think, for places like yours, or maybe even a little different than yours?

CROWLEY: I think it's a huge deal. I mean, 900,000 American households have lost the opportunity to put affordable solar. There's indigenous tribes that have never had their own electricity supply that are impacted. It's poor people that live across the entire country that wanted to do the right thing but didn't have the access to financing in order to get solar installed. All of that has gone up in smoke right now. That's one of the reasons why my organization decided to join into this lawsuit.

CURWOOD: And what about community solar? Wasn't this supposed to fund community solar so even if you didn't have a roof or a building you just rented, you could buy into such solar?

CROWLEY: Exactly. I mean, it's one of the new developments within this marketplace that's pretty exciting. Not everyone's going to be able to put a solar panel on their roof, but it doesn't mean that we can't access solar power. So whether it's community solar, ground-based solar, it's all work that my members do and are still looking forward to doing, but also places where we can really make a dent in our carbon footprint.

CURWOOD: So tell me the story of a community or individual that stands out for you when thinking about the impact that Solar for All could have had.

Rhode Island AFL-CIO President Patrick Crowley says that without the Solar for All program, electricity bills will continue to rise in his state. (Photo: Lex R, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CROWLEY: Well, I think about my brothers in the Electrical Workers Union. It's local 99 here in Rhode Island. They have been doing some pretty innovative work with their apprenticeship programs. They have about a thousand members, and they had several hundred that were working solely in solar, and now all of those jobs have evaporated. You know, they're seeing layoffs for the first time in a number of years because they don't have the access to the projects that are going to be built.

CURWOOD: Okay, hey, Patrick, coming on the line with us now is Kate Sinding Daly, Senior Vice President for Law and Policy at the Conservation Law Foundation, CLF, and one of the lawyers that's representing you folks in this lawsuit. Welcome to Living on Earth as well, Kate.

DALY: Thank you, Steve, good to be with you and good to see you, Pat.

CURWOOD: So we asked you to join us to understand the legalities about this. There's one basic one, standing. Who has the right to sue in a situation like this? You weren't directly going to get any of this money.

DALY: Right, yeah, one of the things that differentiates this case from some of the other cases, where this is not the first program unfortunately, that the Trump administration has canceled, and where folks who have lost grant money have gone to court, is that the plaintiffs in this case are folks who are not the grantees directly themselves, but who would have benefited directly from the grants that were being made under the program. So for example, Pat's organization, the Rhode Island AFL-CIO, as he's described, has hundreds or thousands of workers who would have received jobs because of the grant monies that were made available. Others are homeowners who would have benefited from reduced electricity costs estimated at as much as $400 a year under the implementation of the program. And others are companies who are involved in the installation and would have been direct beneficiaries of the law.

Mr. Crowley says the program would have also opened job opportunities for hundreds of Rhode Island AFL-CIO members. (Photo: Kristian Buus / 10:10, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So it's kind of a missing out lawsuit. How does this work in the law? How can somebody sue when something like this happens, even though they're not actually in the business that's being constrained?

DALY: Well, they are in the business, they're just not the ones who would have received the grant money. But many of these programs contemplate that there needs to be an entity that receives the grant, that enters into a contract with the federal government to receive the money, with the understanding that that entity is then going to either do re-grants or spend the money directly by hiring folks who are going to be building out the solar and connecting it to the grid. So these are folks that can demonstrate a direct financial injury as a result of the actions of the EPA in this case, and that's kind of the quintessential basis for standing as a direct financial injury.

CURWOOD: So walk us through the legal arguments here.

CROWLEY: Sure. So fundamentally, this case involves a deliberate misreading of a statute by EPA to get rid of a program that was contrary to this administration's anti-renewable energy agenda. As Pat indicated, the Solar for All program was created in the Biden administration, and was a function of the Inflation Reduction Act. Earlier this year, Congress passed something that they've euphemistically referred to as the "one big, beautiful bill" law. And that law, among other things, contains a provision that is titled, "Repeal of Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund." And what that does is repeal a provision of the Clean Air Act that was created through the Inflation Reduction Act to develop the Solar for All program. It repeals it, and the unobligated balances of amounts made available to carry out that section are rescinded. So there's that keyword, "unobligated." That means any money that was to flow under the program that had not already been committed to grant recipients was rescinded. Doesn't apply, by its very terms, to money that had already been obligated, and nearly $7 billion had been already obligated under the Solar for All program. And so the main argument in the lawsuit is that what EPA has done is a violation of its authority under the statute, which does not authorize it to repeal or rescind funds that have already been obligated under the program.

Patrick Crowley is the President of Rhode Island AFC-CIO. (Photo: RI AFL-CIO Staff)

CURWOOD: With all that in mind, where does this case stand now and what are the next steps?

DALY: Well, it's been filed, and we're waiting for the government to respond. We are seeking what's known as declaratory and injunctive relief. So we're asking the court both to declare that what EPA did here was against the law, violation both of the Administrative Procedure Act as well as of the Constitution, in violation of separation of powers, and for an injunction that the court order EPA to reinstate the program and get those monies flowing and the benefits flowing to Americans.

CURWOOD: Help us here for any precedent along these lines in some of these other cases that you've seen.

DALY: Well, what I would point to is that there's a roughly a 90% success rate for cases across the board that have challenged the illegal actions of this administration. Those aren't all environmental cases, but that's a pretty impressive win rate, and sadly, a reflection of the fact that this is an administration that does not feel beholden to the law, that seems to feel that they've got the authority to at least try to do anything that they want to do based on their ideological interests.

CURWOOD: We're on the line with Patrick Crowley as well. He's the President of the Rhode Island AFL-CIO, one of the plaintiffs in this case. And let me ask both of you, how does this lawsuit fit into the bigger picture of how President Trump's EPA is managing the rollout of Biden's Bill? Pat?

CROWLEY: Well, I think it just shows the need for everyday Americans and everyday working people like the ones I represent to be vigilant and be ready to take up the case against the administration when they work against our interests. I mean, this is not an isolated attack. We saw it very similarly in offshore wind over the summer, where the Trump administration tried to shut down a revolution wind project that my members are working on. I have a thousand people that were working on that project. It was 80% done, and they just pulled the plug on it. And again, like Kate said, we went right to court, and luckily, an injunction was instituted, and people went right back to work that very same day that the judge made their decision. So we like to say, in Rhode Island, we're a working-class state and we're a fighting state federation. We're going to take the fight to the Trump administration, wherever we think our members' rights are getting violated.

CURWOOD: Kate?

Kate Sinding Daly is the Senior Vice President for Law and Policy at the Conservation Law Foundation. (Photo: Brian Fitzgerald)

DALY: Yeah. I mean, Pat's exactly right. This is part of a pattern in practice from this administration, which has been an aggressively anti-clean energy, renewable energy from day one, including, you know, issuing an executive order on day one that said that they were going to put a stop to offshore wind. But as Pat said, those efforts haven't been successful because they've been violating the law, same way that they did here in doing that. But big picture, the clean energy transition in this country and globally is inevitable. The momentum is not reversible. Clean energy is cheaper than fossil fuels, and it's critically necessary for our public health, for the livability of this planet. So the administration is doing everything they can to try to slow us down, to try to reverse course and get us back on a fossil fuel diet. But they may be able to slow some things down. They're not going to be able to stop or reverse the momentum.

CURWOOD: And Kate, how do you think legal nonprofits such as the Conservation Law Foundation and unions and communities can work together to push back against cuts to green energy grants?

CROWLEY: This case is a great example of folks coming together, the environmental community, the labor community, average homeowners, the renewable energy industry, and saying, let's band together, because we know that this is what's good for our country. This is what's good for Americans and what's needed for a safe future for our children. That's what we're called upon to do.

CURWOOD: Pat, same question to you, how do you think legal nonprofits such as Conservation Law Foundation, communities, unions, how can they work together to push back against these cuts to green energy?

CROWLEY: Well, from our point of view, it just takes organizing, Steve. I mean, one of the things that we did here in Rhode Island a few years ago was we created an organization called Climate Jobs Rhode Island, and it is a coalition of labor unions, community organizations, environmental organizations, that are all fighting for the same cause. I mean, we believe that it's going to be the labor movement that is going to lead this charge. It's human economic activity that is driving climate change. And economic activity means work. So if work is going to be part of the equation, workers need to have their voice heard in the conversation, and that's where the labor movement comes in. So we want to make sure that is the voice for working people across the United States. We have a say in what the transition to a clean economy is going to look like, and we think that we can drive that change with the members that we represent, with the advocacy that we're engaged in, with the organizing that we're known for. We think that if we band together with our allies and our siblings across the entire community that care about the environment that we're going to make a huge difference.

CURWOOD: Patrick Crowley is the president of the Rhode Island AFL-CIO a federation of Labor unions. Kate Sinding Daly is the Senior Vice President for Law and Policy at the Conservation Law Foundation. Thank you both for taking the time with us today.

CROWLEY: Thank you, Steve. I appreciate it.

DALY: Thanks, Steve. It's been a really great conversation.

CURWOOD: The EPA declined to comment on this pending court case.

Related links:

- The Conservation Law Foundation | “New Lawsuit Seeks to Protect $7 Billion in Solar Funding”

- Read the complaint for the Solar for All lawsuit here

- Environmental Protection Agency | “Biden-Harris Administration Launches $7 Billion Solar for All Grant Competition to Fund Residential Solar Programs that Lower Energy Costs for Families and Advance Environmental Justice Through Investing in America Agenda”

- The New York Times | “Groups Sue E.P.A. over Canceled $7 billion for Solar Energy”

- Read more about Rhode Island AFL-CIO

- Read more about the Conservation Law Foundation

[MUSIC: Talking Heads, “The Lady Don’t Mind – 2005 Remaster” on Little Creatures (Deluxe Version) Warner Records Inc.]

DOERING: Coming up, researchers link persistent PFAS chemicals to changes in how genes are expressed. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Waverley Street Foundation, working to cultivate a healing planet with community-led programs for better food, healthy farmlands, and smarter building, energy and businesses.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Candelion, “Betula” Single, Epidemic Sound]

BirdNote®: Melanin Makes Feathers Stronger

Herring gulls have black tipped wings rich in melanin. (Photo: Marie-Lan Taÿ Pamart, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

DOERING: From the classic witch to Batman to Wednesday Addams, dressing in all black is a Halloween staple. But for many birds, black is more than just a fashion statement. Here’s BirdNote®’s Michael Stein to explain.

BirdNote®

Melanin Makes Feathers Stronger

Written by Conor Gearin

[Ring-billed Gull calls]

If you take a look at birds’ wings, you might notice a pattern. Many species have black feathers on the trailing edge of their wings, regardless of what color most of their feathers are. Birds as different as gulls, pelicans, storks, and flamingos all have black-tipped wings.

[American Flamingo flock calls]

These flight feathers are rich in a pigment called melanin. But melanin doesn’t just provide color. It also helps make feathers stronger. Feathers with melanin have a tougher layer of keratin — the same substance found in human fingernails — compared to feathers without. So the black feathers actually help protect a wing from wear and tear.

That’s especially useful on the edge of a birds’ wing, where air is rushing past during flight. Melanin helps the wing stay aerodynamic and efficient for birds so they can gather food, escape from predators, and complete their long migratory journeys.

Pictured above is a Red-necked Phalarope. The black pigment in its wings helps strengthen its feathers. (Photo: Andreas Trepte, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.5)

[Red-necked Phalarope flock calls]

While it takes energy to produce melanin, it saves birds the trouble of replacing feather after feather when traveling thousands of miles.

[Red-necked Phalarope flock calls]

I’m Michael Stein.

###

Senior Producer: Mark Bramhill

Producer: Sam Johnson

Managing Editor: Jazzi Johnson

Content Director: Jonese Franklin

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Ring-billed Gull ML214918231 recorded by Jeff Ellerbusch, American Flamingo ML172484 recorded by Gerrit Vyn, and Red-necked Phalarope ML103332941 recorded by Andrew Spencer.

BirdNote’s theme was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

© 2022 BirdNote March 2022 / 2025

Narrator: Michael Stein

ID# feather-08-2023-03-23 feather-08

Reference:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/241372715_Melanin_and_the_Abra…

https://academy.allaboutbirds.org/how-birds-make-colorful-feathers/

https://www.audubon.org/news/what-makes-bird-feathers-so-colorfully-fab…

https://europepmc.org/article/cba/607575

DOERING: For pictures of these black feathered birds, migrate on over to the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related link:

BirdNote® | “Melanin Makes Feathers Stronger”

[MUSIC: Alan Gogoll, “Honeybee Hill” on Honeybee Hill, Alan Grogoll]

PFAS and Our Genes

PFAS are commonly found in water repellant materials, firefighting foams and are also used in industrial food production. While PFAS are not intentionally added to food or water, they can accidentally leak into the environment, contaminating both. (Photo: MountainFae, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: In late October the European Union will begin to phase out the widespread use of PFAS in firefighting foam, with the restriction approved by both the European Parliament and Council. PFAS are a class of toxic chemicals linked to cancer, immune system suppression, liver and kidney damage and developmental issues in children. They are found in many everyday products, from nonstick pans to water repellant clothing, and their resistance to heat, oil and water makes them a popular and widespread ingredient in firefighting foam. PFAS are very persistent in the environment, especially in ground water, and even small exposures can accumulate in our bodies. A recent study published in the Journal of Environmental Research that sampled firefighters found that exposure to certain PFAS can lead to changes in gene expression. To help us understand how these chemicals can harm us, we’re joined today by lead researcher Dr. Melissa Furlong from the University of Arizona. Dr. Furlong, welcome to Living on Earth!

FURLONG: Thanks Steve, happy to be here.

CURWOOD: So tell me what got you into this research, what prompted you to do this kind of study?

FURLONG: So, right after I graduated from college, I worked at a legal aid office, and part of that job was to do outreach to farm workers to educate them about their legal rights, and we also worked closely with people who would educate farm workers about their pesticide exposures. I, at the time, thought that all chemicals were regulated by the federal government, and that chemicals that were used in the environment were regulated for safety. That year, I was disabused of that notion.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I was gonna say, surprise!

FURLONG: Surprise, yeah, but I learned that a lot of these chemicals, well, particularly pesticides, are designed for toxicity, and just because they are designed for toxicity in insects does not mean that they are safe for humans. And this is because a lot of the targets in insects are actually present in humans, and from there, it was just a slippery slope into learning about all the other chemicals that humans are exposed to that are not necessarily regulated adequately for safety. Recently, I have been interested in working with firefighters, because firefighters are exposed to lots of different environmental chemicals in their service, and the firefighters are particularly concerned about a class of chemicals called PFAS, which stands for per- and polyfluorinated, alkylated substances, and they have slightly higher exposures than the general public.

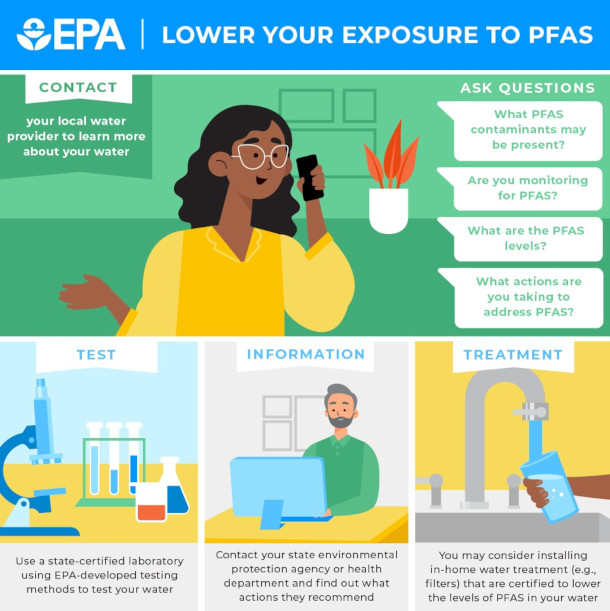

EPA Infographic, "Lower Your Exposure to PFAS." with guidance on ways to decrease individual exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in drinking water. Recommendations include testing your water and installing appropriate water treatment systems. (Photo: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, D.C., Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

CURWOOD: So, the term forever chemicals is often used when describing these fluorinated compounds, PFOAs, and PFAS. How accurate is this term?

FURLONG: Yeah, so we call them forever chemicals because they last a lot longer in the environment than a lot of other modern-use chemicals. They stick around for a few years, up to decades, and that's the same in the body too. There were chemicals that were around a long time ago, that had half-lives of like hundreds of years, if you remember DDT or some of the other organochlorine pesticides, or PCBs, many of those were banned in the 70s, but the half-lives on those were hundreds of years, and we're still exposed to those. So those are the sort of true forever chemicals. PFAS are kind of like modern forever chemicals.

CURWOOD: Now what's the concern about exposure? It could be in a non-stick pan or in a waterproof jacket. What about water and food itself? What risk do we face from PFAS there?

FURLONG: The public is predominantly exposed to PFAS through our water and through contaminated food. It's not intentionally in our food or our water supply, it has just leached into those things because of industrial uses. And close to 100% of people have detectable levels of at least some different types of PFAS species.

CURWOOD: Your study is very exciting because you look at something called microRNA to look at something known as gene expression. Now, for the non-scientists among us, could you explain what microRNA is and how it differs from DNA and messenger RNA—mRNA, and, of course, the whole phenomenon of gene expression?

PFAs, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are human-made chemicals known for their persistence in the environment, sometimes being referred to as “forever chemicals” because they do not break down easily. These substances are not biodegradable and resist degradation by water, heat, or sunlight. Their widespread use and environmental persistence have raised concerns about potential health impacts and environmental contamination. (Photo: Mplanine, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

FURLONG: Sure. So hopefully, everybody is familiar with the concept of DNA, right? Everybody's born with your DNA. Those are your genes. We have a copy of our DNA in every single cell. And the way that the DNA gets turned into who we are, into humans, is the DNA has to get translated into a protein. Part of that process is called DNA expression. So the way that your DNA is expressed eventually makes you who you are, and that is a little bit of a complicated process. So the way that the body turns different parts of our DNA into proteins is through RNA. What messenger RNA does is it copies the relevant section of the DNA, and then that mRNA goes and it eventually turns into some proteins. The microRNA attaches to the messenger RNA. So, sort of on that path between DNA and protein, microRNA changes the way that the genes are expressed, essentially. So an analogy that we like to use sometimes is, let's imagine that the piano is your DNA. The keys don't change, right? But the music that you play, the sheet music that you play, changes the way the piano sounds. And so the sheet music is the expression of the piano, and the sheet music itself can also be changed by the human that is playing the piano. Right? Each person who plays a musical score might sound a little bit different from each other.

CURWOOD: And that individual difference is what the messenger RNA, and indeed, the microRNA can apply to this process.

FURLONG: Right.

CURWOOD: So, your study focuses on changes in gene expression due to exposure to PFAS. Can you clarify the difference between a change in gene expression and a genetic mutation?

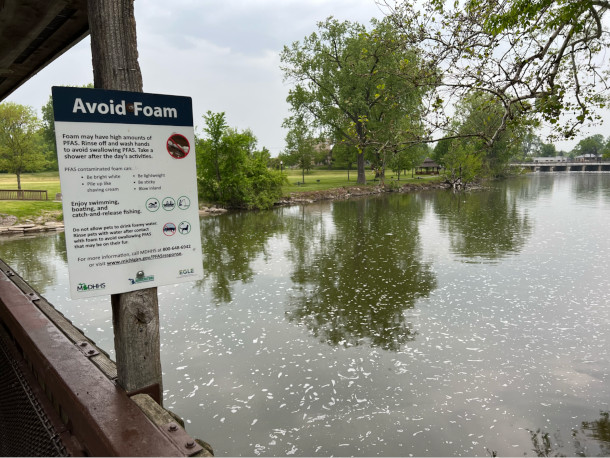

PFAs can contaminate bodies of water and accumulate in the form of foam that behaves similarly to shaving cream. State guidance might notify visitors to prevent people and pets from consuming water from the area. (Photo: MountainFae, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

FURLONG: Yeah, sure. So, a mutation is an actual change in the genome itself. So if we're thinking about a piano like maybe one of your keys is broken or that key doesn't exist, or is out of tune, it sounds wrong. But a change in the gene expression doesn't actually mean there's anything wrong with the underlying DNA. Your underlying DNA can be fully intact. It's just the way that it's translated or transcripted or expressed that is changed.

CURWOOD: So based on your findings, what specific biological pathways or processes does PFAS exposure appear to be disrupting?

FURLONG: Yeah. So, unfortunately, there appeared to be lots of pathways that were affected. We looked at nine different PFAS, and about four of them seemed to be really strongly associated with several different pathways. And basically it came out into three buckets, which were cancers, autoimmune and other immune disorders, and neurological disorders.

CURWOOD: To what extent does our chemical regulatory framework pay attention to how genes are expressed and affected by chemicals?

FURLONG: That's a really good question. So epigenetics is basically the way that our DNA is expressed, and is fairly new in terms of the study of how environmental chemicals affect health outcomes. So we can see these changes in gene expression that are linked to kidney cancer, but it's not proof that exposure to this particular PFAS is definitely going to end up in kidney cancer. So, I don't think that the regulatory framework has been able to incorporate some of these signals quite as readily as they can consider things like a direct association. So it's not an easy thing necessarily to be incorporated into the regulatory framework. The advantage of this kind of study is that, because it's untargeted, we can look at all of these diseases at once. So if we were to look at, you know, every autoimmune disorder, every cancer, every neurological disorder, in a separate study, that would be 10s of millions, possibly hundreds of millions of dollars, right? So we can look to see what's popping up in this untargeted study, and then we can do more targeted looks at some of these specific health outcomes, and hopefully that will eventually turn into stronger evidence that can be used for regulatory purposes.

CURWOOD: Your research focused on firefighters. To what extent do you expect to find similar patterns of disruption of, of genetic expression in the general public from the effects of PFAS?

FURLONG: So we know that firefighters have slightly higher levels of some of the PFAS, but we would assume the dose-response relationship would be the same, even at lower levels of PFAS, and most of the firefighters’ exposure is through the same routes as the general population. They just have some of these additional routes of exposure for some of the specific PFAS, but for the health effects, you know, the way that a PFAS changes gene expression in firefighters should mechanistically be the same as the way it changes gene expression in other people—in the general population.

CURWOOD: So, how concerned do you think the average person should be about their personal exposure to PFAS? I mean, beyond some broad regulatory changes, perhaps, what actionable step might an individual take to reduce the load of PFAS in their daily life?

FURLONG: Yeah, so some people developed pretty severe anxiety about our environmental chemicals, and I understand, because I went through this phase, you know, 10 years ago, when I was first starting this research. But you know, anxiety and stress itself can have some pretty negative health consequences, and the truth is that unless you are highly exposed or genetically sensitive, you are better off worrying about more general health positive behaviors like getting regular exercise and eating a diet that's high in fruits and vegetables and other fibers. However, there are still some relatively easy steps that you can take to reduce your PFAS exposure. So some of those would include using a water filter. A lot of the municipal water supplies, like from your local city, are now trying to treat for PFAS to keep it under certain levels, but you can still install a water filter in your home or use a Brita if a more sophisticated filtration system is out of reach. It's very important to maintain your filters regularly. There's some evidence that your exposures might be higher if you don't change your filters often. And then reducing your consumption of ultra processed foods will also reduce your PFAS exposure and generally be healthier for you. You can also try not to use your non-stick pans. I know it's really hard when you're making scrambled eggs, but if you get a well-seasoned cast iron pan it works just as well, and they're not that expensive. So those are the big ones.

CURWOOD: Melissa Furlong is an environmental epidemiologist at the University of Arizona in Tucson, Arizona. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

FURLONG: Thank you so much, Steve. It was fun talking.

Related links:

- Innovation News Network Europe Cracks Down on PFAS in firefighting foams with new restrictions

- Read the PFAS epigenetic study: “Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and microRNA: An epigenome-wide association study in firefighters”

- Learn more about environmental epidemiologist Melissa Furlong

- Having a hard time visualizing microRNAs and gene expression? Watch this stunning animation on gene regulation by microRNA

- Learn more about PFAS

- Learn more about epigenetics, the study of gene expression

[MUSIC: Oscar Peterson Trio, “D & E” on We Get Requests, The Verve Music Group]

DOERING: Just ahead, taming the monsters of Halloween waste. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the estate of Rosamund Stone Zander - celebrated painter, environmentalist, and author of The Art of Possibility – who inspired others to see the profound interconnectedness of all living things, and to act with courage and creativity on behalf of our planet. Support also comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Oscar Peterson Trio, “D & E” on We Get Requests, The Verve Music Group]

Taming the Monsters of Halloween Waste

Americans are projected to spend more than 3.9 billion dollars on over 600 million pounds of candy this Halloween. (Photo: Nielsoncaetanosalmeron, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Halloween is almost here, and it wouldn’t be the same without the irresistible Reese’s, Milky Ways, and KitKats.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k8MLtrhEN-A

[candy wrapper crackle sounds] [doorbell] Trick or treat! [crackle, crunch sounds] Mmmm…thank you!

DOERING: But what to do about all those candy wrappers? Every year for Halloween, Americans purchase more than 600 million pounds of candy and over 1.3 billion pounds of pumpkins. Here with some ideas for taming the downright frightening levels of Halloween waste is Katie Brewer of Greater Laingsburg Recyclers in Michigan. They’ve been volunteer-led since 1988 and built their first recycling center in 2020 after being an entirely outdoor operation for decades. Katie joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

BREWER: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

DOERING: So we wanted to talk to you today about how we might make Halloween a little bit more sustainable. Can you tell us a bit about your programs and initiatives that are designed to combat holiday waste?

Katie Brewer, front row, far right, and other volunteer members of Greater Laingsburg Recyclers in Michigan host recycling drives four times a month. (Photo: Katie Brewer)

BREWER: Sure. So we're very excited. We love Halloween. So one thing we've been doing, and I think this is our fourth year is collecting candy wrappers. We do that through TerraCycle. It's a free program. So they offer a candy wrapper box specific for Halloween, but they actually let you keep it all fall. So then you can do Christmas and even into Valentine's Day, because all of those holidays involve candy. So people can collect candy wrappers and then bring them to us. We just ask that they be empty, and we collect those, and then send them back through TerraCycle, who then recycles them.

DOERING: I mean, just thinking about, you know, kids going out trick or treating and just how much candy they can collect, and then all the candy wrappers from that, and then there's usually a ton of leftover candy that gets brought into offices and stuff. That's a lot of candy wrappers. And then what happens to these recycled candy wrappers?

BREWER: So the idea, right, is to keep them out of the landfill. They are collected and cleaned through TerraCycle and then turned into other plastic items. So one example would be like, doggy doo-doo bags, that kind of thing. So that's always a good message to send kids too. I think it's helpful that they can see the whole circular economy, like this is how it starts. This is where it goes, and then this is how it ends up.

Greater Laingsburg Recyclers of Laingsburg, Michigan partners with TerraCycle to offer candy wrapper recycling, diverting the waste from landfills. (Photo: Katie Brewer)

DOERING: So I understand that your recycling program, Greater Laingsburg Recyclers, is trying something new this year.

BREWER: Yes.

DOERING: What is “Pitch the Pumpkins”?

BREWER: So we started thinking about an issue in that we have, like, a small bin to collect our food scraps that gets turned into compost. And what happens if someone brings their 12 pumpkins from their porch, it would fill up our entire bin. And so at first we were worried, and we're like, we have to tell people they can't bring their pumpkins. And we're like, wait, is there a better solution? And so we've seen in bigger cities where they collect people's pumpkins and gourds after Halloween. And we thought, well, why can't we do that? So we actually had a connection with someone that has dumpsters and trailers. They're DBD dumpsters here in the Laingsburg area, and we asked them if they would be willing to donate a dumpster at all of our drives in November. So four recycling drives, we will have a dumpster available to collect pumpkins and gourds. And then we partnered with the city, who has, like, a yard waste collection compost area, and they are going to allow us to bring the pumpkins there, and they will be turned into compost, which is amazing, and kept out of the landfill. So we're super excited to do that.

Over 1.3 billion pounds of pumpkins are purchased in the United States each Halloween season. (Photo: Bart Everson, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: I just love that mindset that you know, what was at first, maybe a problem, you guys turned into an opportunity. By the way, how big is Laingsburg?

BREWER: So the city of Laingsburg's population is 1600 but we are not limited to Laingsburg, like we are open to all communities. So we have people driving from a half an hour away, you know, other small towns that don't have recycling or don't have food scrap collection, and we're open to anyone, anyone who would like to come out and bring their items to us or volunteer. We're always looking for new volunteers. That is what keeps us going. It's really important to our mission.

DOERING: So you guys are a really small town, plastic waste and just waste in general is a huge problem globally. What keeps you going, in terms of feeling that this is really important to you, to be collecting candy wrappers and pumpkins and composting them and things like that?

Over $2 billion dollars is spent annually in the US on Halloween candy, with most of the wrappers ending up in landfills. (Photo: Ropable, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

BREWER: Yeah, that's a tricky question. I think seeing the volume that we collect really makes you feel like you're making a difference, like the amount of water bottles. And it's amazing how much we do divert from the landfill. And knowing that if other small towns are making an effort, you know, we don't have curbside recycling in our town. I think Michigan, for a long time, was really low as far as their recycling rates. We are doing so much better now, just in the past five years, we've really increased that. And a lot of that, I think, is awareness, reaching out to kids and going into the school and seeing their reusable water bottles sitting on their desks, and having teachers who are passionate about collecting recycling in the schools. That is something that's really powerful and it keeps me going, so like the little things for sure.

DOERING: So how could other communities use your model to create a volunteer recycling program?

BREWER: So when we decided to build our recycling center, we wanted to make education really important and be kind of like an example for other communities to start a program like this. So we have had other groups come in and look at our facility and so that you know you're not recreating the wheel every time. I know there's some laws, some things happening in Michigan right now, where there has to be recycling for every community within the next few years, so smaller towns that don't have curbside are going to have to have some kind of recycling available for everyone, and so we're a great model for that, and we're more than happy to talk to other towns about how we did it.

Incorporating natural decorations or buying reusable ones that will last more than one Halloween season can help shift waste away from landfills. (Photo: Silar, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 4.0)

DOERING: Do you have any other tips Katie, for celebrating a sustainable Halloween?

BREWER: Absolutely. So I think one of the best tips out there is, if you're going to decorate your house, decorate with nature, use pumpkins, gourds. Go out and pick leaves up, things that can be composted eventually. If you are going to go out and purchase decorations, make them something that will last for years and years to come. You know, I think that's important. It's okay to reuse things. That's what we should strive for. I think thrifting is a great thing. I see my kids get excited about that, like reusing costumes, do a costume swap. There's so much you can do.

DOERING: Yeah, and I think I hear you saying that it doesn't have to be a sacrifice. It can actually be fun, like your kids love thrifting, and they get to do that to find their Halloween costumes.

BREWER: Absolutely, absolutely.

DOERING: Katie Brewer volunteers and serves on the board of Greater Laingsburg Recyclers. Thank you so much, Katie, and Happy Halloween!

BREWER: Thank you.

Related link:

Learn more about how you be a sustainable Halloween participant here

[MUSIC: Halloween Spooky Music Orchestra, “Vampire Waltz” on Halloween Is Here, Ouranio Recordings]

Chicago River Restored to Health

265 athletes swam in the main stem of the Chicago River during the public swim event in 2025. (Photo: Linda Barrett)

CURWOOD: On September 21, hundreds of people put on their bathing suits and leapt into the Chicago River for the first public swimming event since 1927. Famous for being tinted green on St. Patrick’s Day, the Chicago River has joined the ranks of the Seine and other iconic urban waterways that have been restored to some semblance of health. Thanks to a multi-billion-dollar tunnel and reservoir project, swamp restoration and other green infrastructure, it is not only safe for people, many species of fish and other wildlife have also returned. Friends of the Chicago River Executive Director Margaret Frisbie joined Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill.

O'NEILL: This public swimming event was a fundraiser, but its impact actually goes even further than that. What does it mean to you to have public swimming in the Chicago River for the first time in nearly 100 years?

FRISBIE: You know, it was a magical day that's hard to describe, seeing hundreds of people in the water swimming so joyfully, really represented all the work that Friends of the Chicago River and so many organizations and agencies have done to improve the health of the river, not only for people, but for wildlife too. The morning of the swim, people just were beyond thrilled. People were watching from the bridges. They were watching from the Riverwalk. We had incredible media; there was 3 billion media hits. So literally, the whole entire world saw this happen. And for Chicago, what it represents, for people who've lived here a long time, I think it's a game-changer. Seeing people in the water makes you believe that it's possible, and because we have this reputation of being polluted, it's hard to penetrate and get those positive messages out there. And so this is emblematic, literally, of how clean the river is.

Friends of the Chicago River executive director Margaret Frisbie (left) with Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson at the Chicago River Swim on September 21, 2025. (Photo: Courtesy of Margaret Frisbie)

O'NEILL: Yeah, well, tell us about who came to swim there.

FRISBIE: It was so exciting to see who was in the Chicago River for the Chicago River swim. We had Olympic athletes. We had local people. People are getting out of the water saying it was earthy, it was beautiful. It was clean, it was clear. In fact, Becca Mann, who's an Olympic athlete who swims 10Ks in open water, which is really impressive and amazing. She got out and she was just beside herself, and she said, I cannot wait to come back to Chicago and do this again. When you see an Olympic athlete swimming with joy in her heart, you know that this is a river that you're going to enjoy one day like that yourself.

O'NEILL: Well give us a sense of the difference between maybe now and maybe 50 years ago in terms of sewage spills into the river.

FRISBIE: So, when friends of the Chicago River was founded in 1979, on average, there was sewage in the river every three days. Fast Forward 46 years, and basically there's never sewage in the river ever. So having a swim like this is really completely possible every single day of the year. We just have to work on all the other safety protocols to make it okay.

O'NEILL: Margaret tell us a little bit about the ecosystem of the Chicago River.

Friends of the Chicago River volunteers paddle in canoes on Bubbly Creek, picking up trash in 2022. (Photo: Friends of the Chicago River)

FRISBIE: The one thing that's always fun for us to talk about at Friends of the Chicago River is how alive the river is and how different it is. So the World Wildlife Fund has done studies around the world about the decline of biodiversity. And in fact, in the Chicago area, we're seeing our aquatic animal life going up, and that's because of the work of Friends of the Chicago River, the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District, the forest preserves at Cook County and so many partners. And so in the 1970s, when friends was founded, there were less than 10 species of fish in the river system. Now there's nearly 80, and we have beavers and muskrats and turtles, and we're seeing the return of river otters, who are really an excellent sign of river health, because they depend on clean water to keep their coats clean and their bodies healthy, and then they're also dependent upon mussels and fish and other aquatic and macro invertebrates to eat. And so it really is a really terrific sign of how far our river has come from those dark days when there was sewage in the water, on average every three days.

O'NEILL: For those who are unfamiliar, how did we get here? How did we get from a river that couldn't be swum into a river that had this massive swimming fundraiser?

FRISBIE: So 125 years ago, the City of Chicago and our sewage agency actually reversed the Chicago River away from Lake Michigan and designed it into our sewer system. So over the last 50 years, Friends of the Chicago River has been chipping away at both the actual water quality through advocating for cleaning up the river system, but also by using the Clean Water Act and building support for a river that was swimmable. And so the water quality has changed since 1979 when we were founded, bit by bit, you know, using the rules of the Clean Water Act and partnering with government agencies like the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District that dug a huge tunnel and reservoir system that's virtually eliminated sewage from the river system, and then also disinfecting sewage affluent that goes to the river, and just also creating public access so people can get down to and in the water.

Swimmers race in the Chicago River in an event to raise money for ALS research. The next Chicago River public swim is scheduled for Sept. 20, 2026. (Photo: Chris Costoso)

O'NEILL: And so when we talk about cleaning the Chicago River, we were talking about using the Clean Water Act. What actual steps were being taken, how much of this was from a government level versus, you know, a volunteer level? How did that work?

FRISBIE: You know, it's a terrific question, and really it takes both. So the Tunnel and Reservoir Plan is 110 miles of tunnel, three enormous reservoirs that can store 17 billion gallons of sewage and storm water and industrial waste, right? However, it's not just about building it; it's having support for having that system and also making sure that the government agencies who are working on it are on task, and making sure that they're getting the work done. So when the project started in the 1970s, they thought it would be done in the mid 1980s and of course, a $3.2 billion project is going to take a lot longer than that, and they're going to need federal funding. So that's government support, but advocates encouraged and pushed a long ways. So while we partner with this agency, the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District, on many, many programs, we also were engaged with forcing a permit that included an enforceable deadline of 2029 so they have to be done and wrap up the project and not say, hey, we ran out of money, we just can't finish it yet. So it really is that partnership between the advocates like ourselves, representing the people who live here, and then the dedicated scientists and engineers who came up with this big idea. And then, of course, we're also working on green infrastructure to keep storm water out of the system, which also helps eliminate combined sewer overflows.

O'NEILL: What would you consider the biggest challenge during this process of cleaning up the Chicago River?

Festivities at the Dearborn Street bridge during the Chicago River’s first public swim in nearly 100 years. (Photo: Linda Barrett)

FRISBIE: So, you know, Chicago is interesting because, like many cities around the world, we have these combined sewer systems, right? And so people got used to the river systems being a place where sewage and waste could go, as opposed to we're on the shores of Lake Michigan, which everyone fights for and has been caring about for, literally, since Chicago started. So there's a cultural disconnect between our working river and our natural assets, when, in fact, the Chicago River is alive with fish and turtles and muskrats and beavers and all this wildlife. And we have to think about that as a living natural resource versus just this functional waterway, or even once it's cleaned up, one that's a water feature versus a river system.

O'NEILL: So, you know, some people might say, oh, well, you know, the ecosystem's been doing fine for all these years, and we've got beaches anyway. So you know, why is it so important to have a clean Chicago River? What would you say to that?

FRISBIE: There are a number of components to that. First and foremost, the river comes to us. It flows through communities. It's a community connector, and it provides access to nature for people who live in an urban area. We also know that with the impact of the climate crisis, heat is the number one killer, and it is incumbent upon all of us to take seriously the fact that people need public open space where they can go and they can get away from the heat, they can get away from the city. We also know natural areas, so the river and open space and natural areas along it can capture particulate air pollution. We know that nature actually improves public health, and, you know, mental wellness. So it plays so many, many, many roles. And then also we have major biodiversity loss, and cities can play a role in protecting biodiversity. And the Chicago River system is on the Mississippi flyway, so we are getting massive amounts of migratory animals, birds, bats, insects, and they depend on natural areas, and so it's really important for that too.

Friends of the Chicago River executive director Margaret Frisbie. On September 10, Friends of the Chicago River was awarded the Thiess International River Prize from the International River Foundation in recognition of the group’s extraordinary work to restore and revitalize the Chicago-Calumet River system. (Photo: Margaret Frisbie)

O'NEILL: Pollution and sanitation aren't the only things affecting our waterways. To what extent is climate change making an impact on the Chicago River?

FRISBIE: So locally, our climate impact includes heavier, more isolated rain showers. So we've built this big tunnel and reservoir plan infrastructure, but the way that the system was designed, it really wasn't to accommodate that kind of heavy rain. So in certain areas, even when the system can capture the volume, you can still get a combined sewer overflow, and the fact is that ends up sewage the river, which is bad for people in wildlife, but it also washes road salt and fertilizers and other pollutants into the waterway. And so we have to really be careful about where our rain falls, so that we absorb it into the ground and it doesn't end up in the river.

O'NEILL: For many of us, we might hear about the Chicago River once a year, St. Patrick's Day, when it gets dyed green. What do you think about this tradition in the context of all the work that's been done to clean up this river for wildlife and for the people?

FRISBIE: So at Friends of the Chicago River, we think that we have outgrown that tradition. It's really a fun morning. It builds community. People come out, they're so happy, but the river's evolved, and we think the tradition can evolve. And so we could come up with new ideas, you know, big, giant green shamrocks that melt away into nothing, or, you know, just, there's a host of ways to come up that you can still build that joy. But we think, you know, a river that's alive with wildlife really needs to be treated like a natural resource, not, you know, a candy-colored green toy that we can play with. And so we're hopeful that we'll evolve in Chicago. And I think if people imagined and understood that, say, a beaver swimming downtown through that green dye, they might rethink it and think, oh, maybe it's time to stop this and think about something else.

CURWOOD: Margaret Frisbie, Executive Director of Friends of the Chicago River, speaking with Living on Earth’s Aynsley O’Neill. And if you missed this first big swim in the Chicago River, you could mark your calendars for next year’s big public swim.

That’s September 20, 2026.

Related links:

- Chicago River Swim

- Visit the Friends of the Chicago River website

- Chicago’s Tunnel and Reservoir Plan

- WBUR | “Swimmers Race in the Chicago River for the First Time in Nearly 100 Years”

[MUSIC: Staffan Carlén, “Lake Michigan” Single, Epidemic Sound]

DOERING: Next time on Living on Earth, a toxic spill from a copper mine in Zambia. Mining, climate justice and the energy transition.

SURMA:I mean, I think the starting place is acknowledging that climate change has to be addressed. We're breaching limits that scientists have said keep us within a safe operating space for humans. That being said, you know, by just saying we need to deploy more renewable energy without addressing those deeper justice issues, that's, it's not a solution. When I talk to sources in South America or Africa, they see the global north's energy transition as green colonialism and beyond the pollution, mining also is dangerous in terms of environmental defenders, people who try to defend their territories to protect it from harm. And I think the latest numbers are something like 320 human rights defenders are killed every year, and most of them are environmental defenders. One source said people here die so that people in your country can drive electric SUVs. Just think we have to grapple with these difficult issues. It's a really hard problem to solve, but I don't think you know it serves us to not recognize these justice issues.

DOERING: That's next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Staffan Carlén, “Lake Michigan” Single, Epidemic Sound]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Sophie Bokor, Daniela Faria, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jade Poli, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio, and we always welcome your feedback at comments@loe.org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth