The Real Cost of Beef

Air Date: Week of October 24, 2025

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon state of Matto Grosso. Deforestation in the Amazon area is driven mainly by industry and agriculture. Mato Grosso means "Thick Woods", and widespread forest clearing in the state has had a dramatic impact on the land. Forest clearing has been centralized mostly along new roadways cut through the jungle. (Photo: Riccardo Pravettonim, GRID-Arendal Resources Library, www.grida.no/resources/3127)

A recent Human Rights Watch report found that illegal cattle ranching and clearing of the Amazon rainforest has led to the forced eviction of small farmers and indigenous people in the state of Pará, Brazil. The report also alleges that cattle raised on these illegal ranches may be sold to middlemen who are often direct suppliers for JBS, the world’s largest meat company. Luciana Tellez Chavez helped compile the report for Human Rights Watch and she joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss the stakes for the planet and people, as well as possible solutions.

Transcript

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

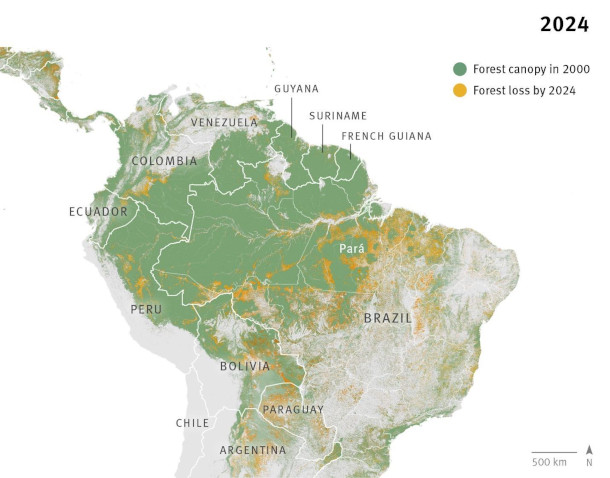

Global forests are in crisis, with 20 million acres lost in 2024, according to a coalition of civil society and research organizations called Climate Focus. And they say the world is not on track to halt forest loss by 2030, a key goal outlined at the Glasgow UN Climate Conference in 2021.

DOERING: A major driver of this continued deforestation is agriculture, which is displacing both forests and people in the Brazilian Amazon. As part of agrarian reforms that go back to the 1980s, the Brazilian federal government has set aside rural settlements for small holders to attain a sustainable livelihood and preserve the rain forest.

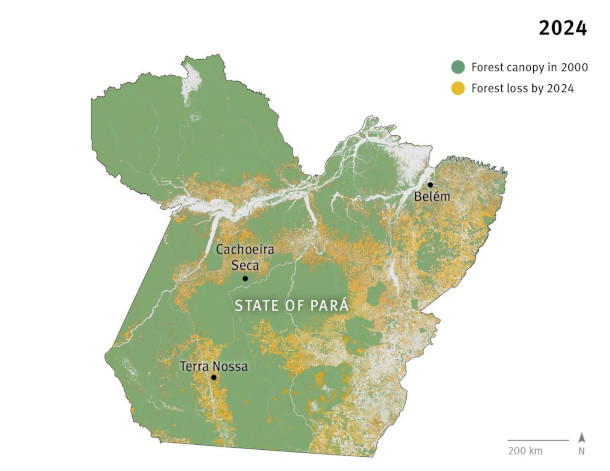

BELTRAN: But a recent Human Rights Watch report found that illegal cattle ranching has led to the forced eviction of many of these small holders in the Terra Nossa settlement, as well as the Arara indigenous people of the Cachoeira Seca territory, both in the state of Pará. Researchers describe a three-step process that begins with illegal logging of valuable old growth forests, followed by burning and clearing, and then seeding for pastures.

DOERING: Human Rights Watch researchers also allege that cattle raised on these illegal ranches may be sold to middlemen who are often direct suppliers for JBS, the world’s largest meat company. Luciana Tellez Chavez helped compile the report for Human Rights Watch and she joins me now from São Paulo. Luciana, welcome to Living on Earth!

CHÁVEZ: Thank you, Jenni. It's pleasure to be here.

DOERING: So your study showed that illegal cattle ranching has really devastated the territories of these small landholders and indigenous communities. What does that devastation look like?

CHÁVEZ: You know, I was in Terra Nossa in November, and it was really heartbreaking. You know, for example, I was meeting this community leader who's represented small holders for years. She's advocated for their rights. She survived an assassination attempt on her after, you know, she denounced the illegal encroachment, a really courageous woman. And she was showing me where these huge Brazil nut trees used to stand you know, she planted them. She used to harvest the nuts and sell them in local markets. She was like, this is a good livelihood. You get a better livelihood from a standing forest than from 1,000 cattle. That was her perspective. And she told me in a few minutes, I lost the work that I put into this land for 17 years because these illegal cattle ranchers set these devastating fires that basically destroyed her crops, the crops of many other legal residents in the settlement. And it's really a tragedy to see a community that was making a sustainable livelihood be so thoroughly devastated by what it's purely criminal activity. You know, there's no ambiguity about the illegality of the cattle ranches that have established themselves in Terra Nossa without permission from the federal government. And similarly, in Cachoeira Seca, it's a kind of a knock-on effect, because, of course, for indigenous peoples, there's a spiritual and identitarian attachment to the land. So the illegal cattle ranching on the Cachoeira Seca territory, because they are so outnumbered, the Arara indigenous people don't feel free to move about their territory however they wish, because they are afraid of encountering these illegal cattle ranchers. And as a result of that, they are less likely to go out hunting further out into their territory. And this is a group that really relies on hunting for other reasons. For example, teaching the young about the rainforest, about the plants that are useful for medicinal purposes or for eating and for transmitting knowledge to younger generations. So it has also an effect on the ability of this group to maintain their culture.

DOERING: Wow, so whether it's someone like the woman that you mentioned, who had the Brazil nut trees, or whether it's just also happening in the vicinity, it's having these effects on communities.

This map shows the decline of the Amazon Forest Canopy between 2000 and 2024. (Photo: Courtesy of Human Rights Watch)

CHÁVEZ: Absolutely. What's really frustrating is to see the lack of action on the part of the federal government to address this encroachment, because, like I mentioned, there's no ambiguity about the illegality of the encroachment on these territories. So the reasons, the grounds to take action are there, but it's been very delayed, so and it has an enormous cost, because for the case of Terra Nossa, you know, this is a settlement that, when it was created in 2006, 80 percent of it was covered by primary rainforest. Now, 40 percent of the settlement is covered in pasture because of the encroachment of these illegal cattle ranches. And then, in the case of Cachoeira Secca in 2024 it was the most deforested indigenous territory in the Brazilian Amazon. And again, the leading driver is this illegal cattle ranching. The cost of inaction is very high.

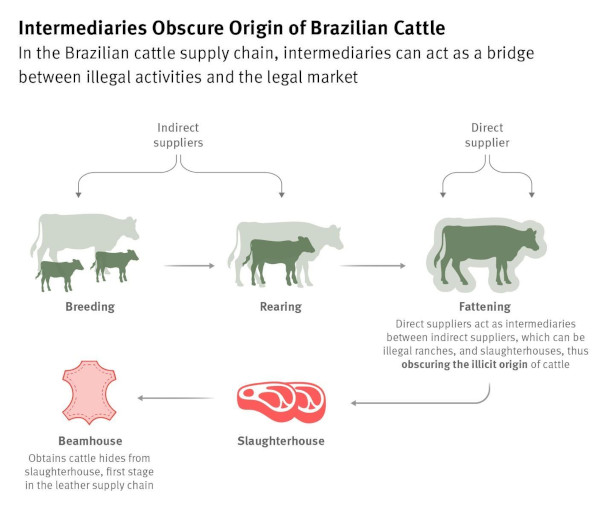

DOERING: So Luciana, your research showed that products from these illegal farms could be ending up in the JBS supply chain and on dinner tables in Europe and elsewhere. So how might this illegally farmed beef be getting into JBS’s supply chain?

Map of the State of Pará, which will host COP30 Brazil this fall in Belem. The map shows the decline of the forest in the past 24 years, in part due to the invasion of illegal cattle ranches and other agricultural industries. (Photo: Courtesy of Human Rights Watch)

CHÁVEZ: We're not able to show definitively that JBS bought the cattle that was illegally raised in these ranches. But the thing is, JBS is also not able to definitively rule out that that illegal cattle is in their supply chain. So let me explain quickly how that goes. You have these illegal ranches operating in these protected forests, and they will sell to one or several intermediary ranches, and those ranches at the end, they are the direct suppliers for JBS. So they are the ranches that JBS directly purchases cattle from. Now, JBS traces its direct suppliers. That means it analyzes which ranches it is buying from directly and whether they comply with some sustainability and human rights criteria, but it doesn't extend that analysis to its indirect suppliers. So those are basically the in the case I just described, those would be potentially the illegal cattle ranches operating in Terra Nossa and Cachoeira Seca, so the fact that JBS doesn't have visibility over its entire supply chain does not allow it to rule out that it may be acquiring cattle that's coming from illegal ranches, and that's the problem that we highlight in the report.

DOERING: What has JBS said about why they aren't tracing these cattle all the way back?

Human Rights Watch’s report “Tainted” alleges that beef from illegal cattle ranches in the Amazon could potentially be entering the JBS supply chain and ending up on dinner tables in Europe since JBS does not track cattle beyond its direct supplier. The infographic shows how cattle get from pasture to slaughterhouse. (Photo: Courtesy of Human Rights Watch)

CHÁVEZ: Well, they haven't so much explained why they haven't traced it all back. Though I should note two things. One is that in 2009, JBS committed to tracing its indirect suppliers by 2011. We are now in 2025, 14 years later, and JBS still is not tracing its indirect suppliers. But it has promised to do so by next January, and we eagerly await that development, of course, but we'll have to see what the system looks like in practice. Is it robust? Can it withstand fraud attempts? What kind of documentation is used to actually check the claims made by the different suppliers? There's a number of different things that we would like to see before we could really tell, you know, how confident we feel in that system. But from our perspective, the ideal solution would be one that's imposed by the government at a federal level. So to establish a traceability system for the whole of Brazil that would essentially it would be something like issuing a little passport to each animal, so that anytime a buyer is going to acquire cattle, they know every ranch the animal has been through before it came to the slaughterhouse. And this would give basically all companies visibility over their supply chain. It would make it a lot harder for illegal cattle ranches to be able to launder the animals that come from deforested areas, and ultimately for buyers, both in Brazil and abroad, it would give more confidence that the product they're acquiring is not coming from an illegal origin. So that's kind of the state of affairs right now. I have to highlight that Brazil has taken a positive step in this direction, because last December, it announced it would establish a federal traceability system for cattle. But it also announced that it would take a full eight years for that system to be fully operational, and with all the tipping points that seem to be in the horizon for the Amazon and other ecosystems, we really have to question whether the Amazon has that kind of time.

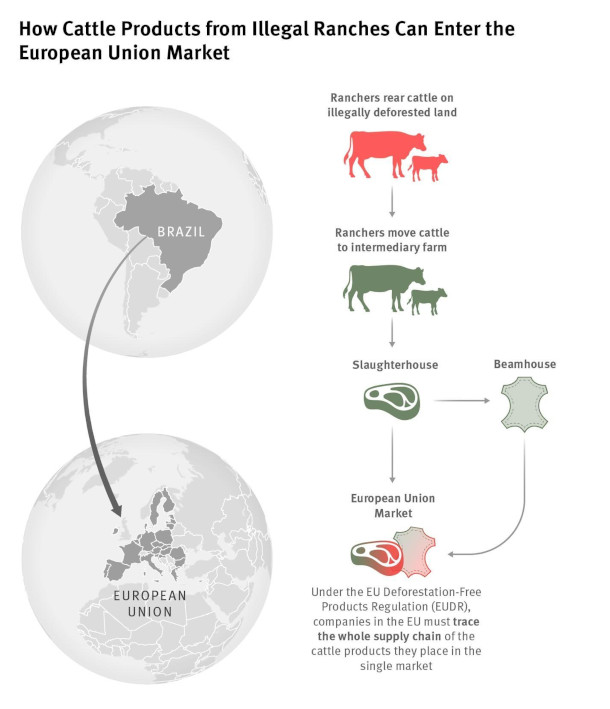

DOERING: And by the way, now there's a lot of pressure from the European Union, which has these regulations requiring cattle to be deforestation-free and traceability. So how much pressure is there on JBS to comply with those regulations and ensure that it can continue selling its meat on the European market?

This infographic shows how cattle products from illegal ranches in Brazil can enter the European Union Market as steak and handbags. The EU is scheduled to begin enforcing its anti-deforestation regulations in January 2026. (Photo: Courtesy of Human Rights Watch)

CHÁVEZ: So the EU deforestation-free products regulation applies to all 27 member states of the European Union. So if you're a company that's operating in the EU, you have to comply with this law. So what that means is that ultimately, if you want to buy products from JBS in Brazil and then sell them in the EU, those products have to be compliant with the regulation.

DOERING: Talk to me about what the local state government there in Pará can be doing to prevent this laundering of cattle, essentially, you know, raising cattle on illegal land, deforested land, and then passing it off to a different ranch where it looks like everything's fine.

CHÁVEZ: Yes, it's actually quite encouraging, because the state of Pará has introduced its own cattle traceability system. The purpose of this system is essentially to trace every ranch that an animal has been through during their lifetime before it is sent to the slaughterhouse. And it aims to have it fully operational in three years. Three years, versus eight years for the plan of the federal government. So the plan of Pará state is much more ambitious in terms of its timeline. But you know, the challenge ultimately is that the cattle laundering, it's a cross-border problem. So what we found was that illegal ranches that are located in Pará are selling to middlemen, and these middlemen are selling to JBS slaughterhouses located, yes, in the state of Pará, but also in the state of Mato Grosso and even the state of São Paulo. So the problem, you know, like, ends up reaching very far. And if you don't have a federal solution to the problem, the fact that Pará kind of puts in place a more robust system is just going to be like squeezing a balloon, and it's just going to pop up somewhere else.

Luciana Téllez Chávez, Senior Researcher in the Environment and Human Rights Division, Human Rights Watch. (Photo: Luciana Téllez Chávez)

DOERING: Luciana, this report is being issued on the eve of the big UN climate meeting COP30 in Brazil, which is being held in Pará. What message does this report send?

CHÁVEZ: The message we want to send with this report is that there are communities who are trying to develop sustainable livelihoods in the Amazon, and they are under enormous pressure from illegal cattle ranching. So for the government to create space for this bio economy to thrive in the Amazon, it needs to deal with this illegal cattle ranching head on and hold perpetrators accountable and pass reforms that are broad ranging and essentially prevent this problem from repeating itself in the future on the same scale. In addition, we're also saying folks that buy these products domestically and abroad have a responsibility to make sure they're not contributing to the problem. So what we really want to emphasize is that everybody has a role to play in protecting the Amazon and everybody has to own that responsibility and take action consequently. And in the end, this is an issue that is fundamentally about Brazil, because it is the Brazilian Amazon, and it's first and foremost, a Brazilian responsibility, but because Brazil is such a large exporter of products all over the world, ultimately, people buying these products all over the world have a responsibility of their own and that they can act upon.

DOERING: Luciana Téllez Chåvez is a senior researcher in the Environment and Human Rights Division of Human Rights Watch, and she helped compile this report. Thank you so much, Luciana.

CHÁVEZ: Thank you, Jenni. It was a pleasure to be on Living on Earth.

DOERING: JBS referred us to the Brazilian Beef Exporters Association, which called the Human Rights Watch report “weak and methodologically flawed” and said that quote, “The publication recycles outdated and debunked narratives, disregarding the environmental progress achieved by Brazil and the public policies implemented to enhance production sustainability.” We’ll post the full statement on the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Links

Al Jazeera | “Is Your Beef Linked to Amazon Deforestation? A Report Highlights Loopholes”

Politico | “Brussels U-Turns on Anti-Deforestation Law Delay”

Brazil Beef Exporters Association (ABIEC) statement in response to Human Rights Watch Report.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth