October 24, 2025

Air Date: October 24, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Real Cost of Beef

View the page for this story

A recent Human Rights Watch report found that illegal cattle ranching and clearing of the Amazon rainforest has led to the forced eviction of small farmers and indigenous people in the state of Pará, Brazil. The report also alleges that cattle raised on these illegal ranches may be sold to middlemen who are often direct suppliers for JBS, the world’s largest meat company. Luciana Tellez Chavez helped compile the report for Human Rights Watch and she joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss the stakes for the planet and people, as well as possible solutions. (13:19)

Media and the Meat Habit

View the page for this story

Meat is the biggest single source of carbon emissions from the food system, which is itself responsible for a third of global greenhouse gas emissions. Sociologist David McBey from the University of Aberdeen in Scotland joins Host Paloma Beltran to talk about the gap between reality and coverage of how meat contributes to global warming, as well as effective strategies for encouraging people to choose to eat less meat without trying to force them to do so. (09:40)

Overseas Chinese Mining and Spills

View the page for this story

As part of the Belt and Road Initiative, China has invested over $1 trillion in overseas infrastructure for projects that include mining in developing countries for minerals to fuel the clean energy transition. In the “copper belt” of Zambia, a Chinese-owned tailings dam collapsed, sending toxic sludge into homes and crops. Inside Climate News reporter Katie Surma speaks with Host Jenni Doering about the aftermath and “green colonialism” that appears to no longer be only at the hands of the Global North. (09:12)

Rebuilding Back Better After Wildfire

View the page for this story

David Brancaccio, the host of Marketplace Morning Report, is no stranger to climate disruption. He lost his home in the devastating Los Angeles fires this past January only two months after moving in. Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood checked back in with David Brancaccio to hear about his hopes to rebuild with fire-resistant material. (13:06)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

251024 Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: David Brancaccio, Luciana Tellez Chavez, Caroline Fraser, Dr. David McBey, Katie Surma

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Deforestation in the Amazon is linked to illegal cattle ranching and lack of transparency.

TELLEZ CHAVEZ: The fact that JBS doesn’t have visibility over its entire supply chain does not allow it to rule out that it may be acquiring cattle that’s coming from illegal ranches. And that’s the problem that we highlight in the report.

DOERING: Also, rebuilding stronger after the L.A. wildfires using engineered wood.

BRANCACCIO: In a fire, they're quite hardy, they're better than steel, tests show. When you put 2000 degrees of flame on these things, they blacken with soot, and the soot becomes a barrier layer, and it doesn't burn through. You'd have to fix it, but hopefully it would keep the fire from entering the interior of the house.

DOERING: Those stories and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

The Real Cost of Beef

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon state of Matto Grosso. Deforestation in the Amazon area is driven mainly by industry and agriculture. Mato Grosso means "Thick Woods", and widespread forest clearing in the state has had a dramatic impact on the land. Forest clearing has been centralized mostly along new roadways cut through the jungle. (Photo: Riccardo Pravettonim, GRID-Arendal Resources Library, www.grida.no/resources/3127)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

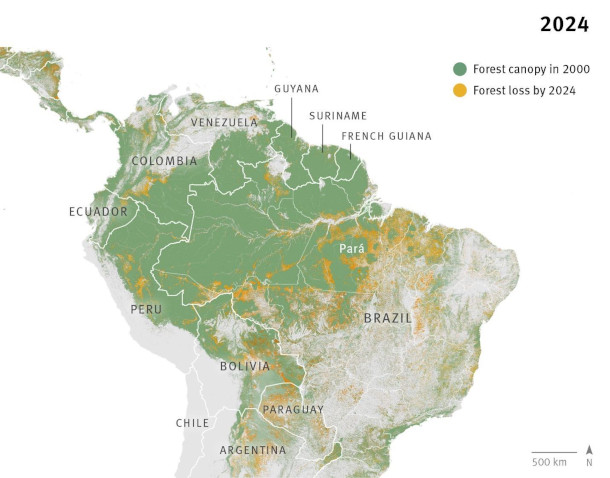

Global forests are in crisis, with 20 million acres lost in 2024, according to a coalition of civil society and research organizations called Climate Focus. And they say the world is not on track to halt forest loss by 2030, a key goal outlined at the Glasgow UN Climate Conference in 2021.

DOERING: A major driver of this continued deforestation is agriculture, which is displacing both forests and people in the Brazilian Amazon. As part of agrarian reforms that go back to the 1980s, the Brazilian federal government has set aside rural settlements for small holders to attain a sustainable livelihood and preserve the rain forest.

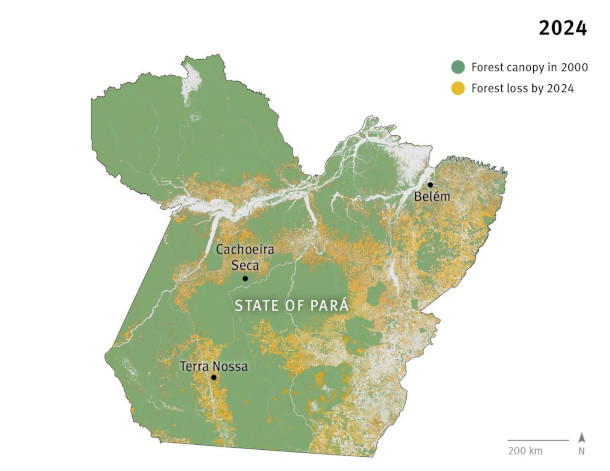

BELTRAN: But a recent Human Rights Watch report found that illegal cattle ranching has led to the forced eviction of many of these small holders in the Terra Nossa settlement, as well as the Arara indigenous people of the Cachoeira Seca territory, both in the state of Pará. Researchers describe a three-step process that begins with illegal logging of valuable old growth forests, followed by burning and clearing, and then seeding for pastures.

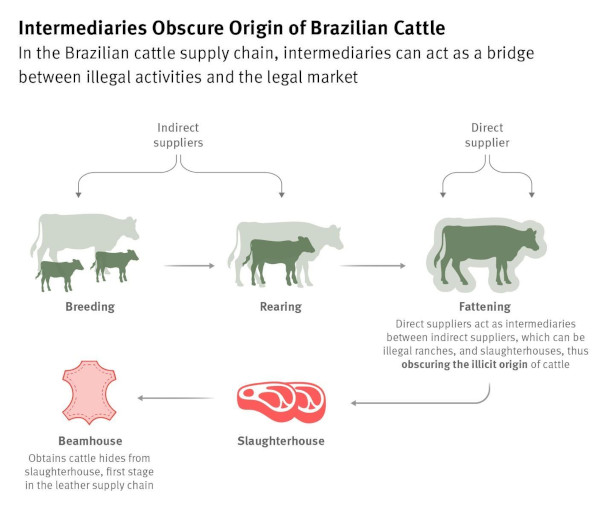

DOERING: Human Rights Watch researchers also allege that cattle raised on these illegal ranches may be sold to middlemen who are often direct suppliers for JBS, the world’s largest meat company. Luciana Tellez Chavez helped compile the report for Human Rights Watch and she joins me now from São Paulo. Luciana, welcome to Living on Earth!

CHÁVEZ: Thank you, Jenni. It's pleasure to be here.

DOERING: So your study showed that illegal cattle ranching has really devastated the territories of these small landholders and indigenous communities. What does that devastation look like?

CHÁVEZ: You know, I was in Terra Nossa in November, and it was really heartbreaking. You know, for example, I was meeting this community leader who's represented small holders for years. She's advocated for their rights. She survived an assassination attempt on her after, you know, she denounced the illegal encroachment, a really courageous woman. And she was showing me where these huge Brazil nut trees used to stand you know, she planted them. She used to harvest the nuts and sell them in local markets. She was like, this is a good livelihood. You get a better livelihood from a standing forest than from 1,000 cattle. That was her perspective. And she told me in a few minutes, I lost the work that I put into this land for 17 years because these illegal cattle ranchers set these devastating fires that basically destroyed her crops, the crops of many other legal residents in the settlement. And it's really a tragedy to see a community that was making a sustainable livelihood be so thoroughly devastated by what it's purely criminal activity. You know, there's no ambiguity about the illegality of the cattle ranches that have established themselves in Terra Nossa without permission from the federal government. And similarly, in Cachoeira Seca, it's a kind of a knock-on effect, because, of course, for indigenous peoples, there's a spiritual and identitarian attachment to the land. So the illegal cattle ranching on the Cachoeira Seca territory, because they are so outnumbered, the Arara indigenous people don't feel free to move about their territory however they wish, because they are afraid of encountering these illegal cattle ranchers. And as a result of that, they are less likely to go out hunting further out into their territory. And this is a group that really relies on hunting for other reasons. For example, teaching the young about the rainforest, about the plants that are useful for medicinal purposes or for eating and for transmitting knowledge to younger generations. So it has also an effect on the ability of this group to maintain their culture.

DOERING: Wow, so whether it's someone like the woman that you mentioned, who had the Brazil nut trees, or whether it's just also happening in the vicinity, it's having these effects on communities.

This map shows the decline of the Amazon Forest Canopy between 2000 and 2024. (Photo: Courtesy of Human Rights Watch)

CHÁVEZ: Absolutely. What's really frustrating is to see the lack of action on the part of the federal government to address this encroachment, because, like I mentioned, there's no ambiguity about the illegality of the encroachment on these territories. So the reasons, the grounds to take action are there, but it's been very delayed, so and it has an enormous cost, because for the case of Terra Nossa, you know, this is a settlement that, when it was created in 2006, 80 percent of it was covered by primary rainforest. Now, 40 percent of the settlement is covered in pasture because of the encroachment of these illegal cattle ranches. And then, in the case of Cachoeira Secca in 2024 it was the most deforested indigenous territory in the Brazilian Amazon. And again, the leading driver is this illegal cattle ranching. The cost of inaction is very high.

DOERING: So Luciana, your research showed that products from these illegal farms could be ending up in the JBS supply chain and on dinner tables in Europe and elsewhere. So how might this illegally farmed beef be getting into JBS’s supply chain?

Map of the State of Pará, which will host COP30 Brazil this fall in Belem. The map shows the decline of the forest in the past 24 years, in part due to the invasion of illegal cattle ranches and other agricultural industries. (Photo: Courtesy of Human Rights Watch)

CHÁVEZ: We're not able to show definitively that JBS bought the cattle that was illegally raised in these ranches. But the thing is, JBS is also not able to definitively rule out that that illegal cattle is in their supply chain. So let me explain quickly how that goes. You have these illegal ranches operating in these protected forests, and they will sell to one or several intermediary ranches, and those ranches at the end, they are the direct suppliers for JBS. So they are the ranches that JBS directly purchases cattle from. Now, JBS traces its direct suppliers. That means it analyzes which ranches it is buying from directly and whether they comply with some sustainability and human rights criteria, but it doesn't extend that analysis to its indirect suppliers. So those are basically the in the case I just described, those would be potentially the illegal cattle ranches operating in Terra Nossa and Cachoeira Seca, so the fact that JBS doesn't have visibility over its entire supply chain does not allow it to rule out that it may be acquiring cattle that's coming from illegal ranches, and that's the problem that we highlight in the report.

DOERING: What has JBS said about why they aren't tracing these cattle all the way back?

Human Rights Watch’s report “Tainted” alleges that beef from illegal cattle ranches in the Amazon could potentially be entering the JBS supply chain and ending up on dinner tables in Europe since JBS does not track cattle beyond its direct supplier. The infographic shows how cattle get from pasture to slaughterhouse. (Photo: Courtesy of Human Rights Watch)

CHÁVEZ: Well, they haven't so much explained why they haven't traced it all back. Though I should note two things. One is that in 2009, JBS committed to tracing its indirect suppliers by 2011. We are now in 2025, 14 years later, and JBS still is not tracing its indirect suppliers. But it has promised to do so by next January, and we eagerly await that development, of course, but we'll have to see what the system looks like in practice. Is it robust? Can it withstand fraud attempts? What kind of documentation is used to actually check the claims made by the different suppliers? There's a number of different things that we would like to see before we could really tell, you know, how confident we feel in that system. But from our perspective, the ideal solution would be one that's imposed by the government at a federal level. So to establish a traceability system for the whole of Brazil that would essentially it would be something like issuing a little passport to each animal, so that anytime a buyer is going to acquire cattle, they know every ranch the animal has been through before it came to the slaughterhouse. And this would give basically all companies visibility over their supply chain. It would make it a lot harder for illegal cattle ranches to be able to launder the animals that come from deforested areas, and ultimately for buyers, both in Brazil and abroad, it would give more confidence that the product they're acquiring is not coming from an illegal origin. So that's kind of the state of affairs right now. I have to highlight that Brazil has taken a positive step in this direction, because last December, it announced it would establish a federal traceability system for cattle. But it also announced that it would take a full eight years for that system to be fully operational, and with all the tipping points that seem to be in the horizon for the Amazon and other ecosystems, we really have to question whether the Amazon has that kind of time.

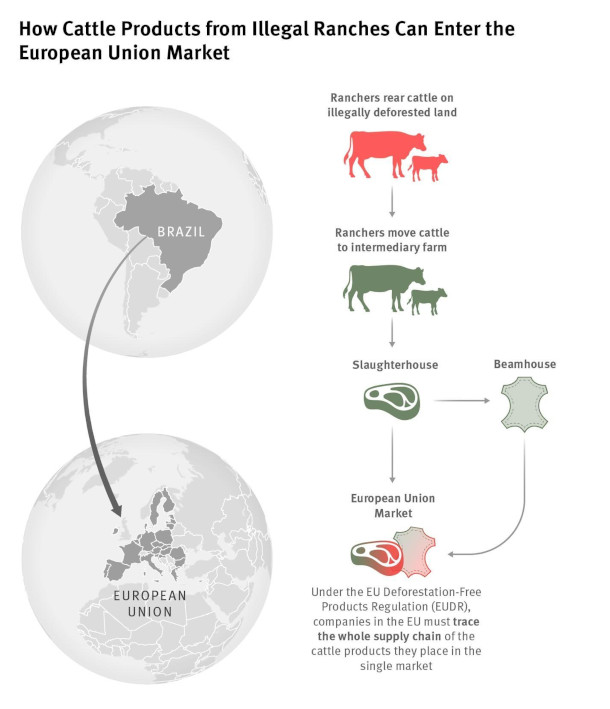

DOERING: And by the way, now there's a lot of pressure from the European Union, which has these regulations requiring cattle to be deforestation-free and traceability. So how much pressure is there on JBS to comply with those regulations and ensure that it can continue selling its meat on the European market?

This infographic shows how cattle products from illegal ranches in Brazil can enter the European Union Market as steak and handbags. The EU is scheduled to begin enforcing its anti-deforestation regulations in January 2026. (Photo: Courtesy of Human Rights Watch)

CHÁVEZ: So the EU deforestation-free products regulation applies to all 27 member states of the European Union. So if you're a company that's operating in the EU, you have to comply with this law. So what that means is that ultimately, if you want to buy products from JBS in Brazil and then sell them in the EU, those products have to be compliant with the regulation.

DOERING: Talk to me about what the local state government there in Pará can be doing to prevent this laundering of cattle, essentially, you know, raising cattle on illegal land, deforested land, and then passing it off to a different ranch where it looks like everything's fine.

CHÁVEZ: Yes, it's actually quite encouraging, because the state of Pará has introduced its own cattle traceability system. The purpose of this system is essentially to trace every ranch that an animal has been through during their lifetime before it is sent to the slaughterhouse. And it aims to have it fully operational in three years. Three years, versus eight years for the plan of the federal government. So the plan of Pará state is much more ambitious in terms of its timeline. But you know, the challenge ultimately is that the cattle laundering, it's a cross-border problem. So what we found was that illegal ranches that are located in Pará are selling to middlemen, and these middlemen are selling to JBS slaughterhouses located, yes, in the state of Pará, but also in the state of Mato Grosso and even the state of São Paulo. So the problem, you know, like, ends up reaching very far. And if you don't have a federal solution to the problem, the fact that Pará kind of puts in place a more robust system is just going to be like squeezing a balloon, and it's just going to pop up somewhere else.

Luciana Téllez Chávez, Senior Researcher in the Environment and Human Rights Division, Human Rights Watch. (Photo: Luciana Téllez Chávez)

DOERING: Luciana, this report is being issued on the eve of the big UN climate meeting COP30 in Brazil, which is being held in Pará. What message does this report send?

CHÁVEZ: The message we want to send with this report is that there are communities who are trying to develop sustainable livelihoods in the Amazon, and they are under enormous pressure from illegal cattle ranching. So for the government to create space for this bio economy to thrive in the Amazon, it needs to deal with this illegal cattle ranching head on and hold perpetrators accountable and pass reforms that are broad ranging and essentially prevent this problem from repeating itself in the future on the same scale. In addition, we're also saying folks that buy these products domestically and abroad have a responsibility to make sure they're not contributing to the problem. So what we really want to emphasize is that everybody has a role to play in protecting the Amazon and everybody has to own that responsibility and take action consequently. And in the end, this is an issue that is fundamentally about Brazil, because it is the Brazilian Amazon, and it's first and foremost, a Brazilian responsibility, but because Brazil is such a large exporter of products all over the world, ultimately, people buying these products all over the world have a responsibility of their own and that they can act upon.

DOERING: Luciana Téllez Chåvez is a senior researcher in the Environment and Human Rights Division of Human Rights Watch, and she helped compile this report. Thank you so much, Luciana.

CHÁVEZ: Thank you, Jenni. It was a pleasure to be on Living on Earth.

DOERING: JBS referred us to the Brazilian Beef Exporters Association, which called the Human Rights Watch report “weak and methodologically flawed” and said that quote, “The publication recycles outdated and debunked narratives, disregarding the environmental progress achieved by Brazil and the public policies implemented to enhance production sustainability.” We’ll post the full statement on the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Human Rights Watch | “Tainted: JBS and EU’s Exposure to Human Rights Violations and Illegal Deforestation in Pára, Brazil”

- Al Jazeera | “Is Your Beef Linked to Amazon Deforestation? A Report Highlights Loopholes”

- Politico | “Brussels U-Turns on Anti-Deforestation Law Delay”

- Brazil Beef Exporters Association (ABIEC) statement in response to Human Rights Watch Report.

MUSIC: Central Park Quartet, “Bossa Carioca” Single, Prisma Music]

BELTRAN: Coming up, real strategies that actually encourage us to eat less meat. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Waverley Street Foundation, working to cultivate a healing planet with community-led programs for better food, healthy farmlands, and smarter building, energy and businesses.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Central Park Quartet, “Bossa Carioca” Single, Prisma Music]

Media and the Meat Habit

Methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, enters the atmosphere through the digestive processes of livestock such as cows, contributing significantly to global warming. (Photo: Trougnouf, Wikimedia Commons, BY CC 4.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

From Thanksgiving turkey to 4th of July hot dogs, meat is a staple in American culture. According to the USDA, the average American eats roughly 225 pounds of red meat and poultry every year, and all that meat carries a pretty hefty carbon footprint. And as economies grow, global diets are becoming more meat centric. But meat’s connection to the climate crisis is largely underreported in major news outlets. Sentient Media, a non-profit news organization focused on creating transparency around factory farming and its impact on the climate, conducted an analysis that found that 96% of climate news stories don’t cover animal agriculture as a major pollution source. To help us understand why, and what strategies might address the climate costs of our meat-eating habits, we’re joined by sociologist Dr. David McBey from the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. David, welcome to Living on Earth!

MCBEY: Thank you very much for having me.

BELTRAN: So David, tell us a little bit more about the meat industry and meat consumption. How are they major players in carbon emissions?

MCBEY: Yeah, so the entire food system is responsible for around about a third of global greenhouse gas emissions, and of that, meat is the biggest sort of single cause. I mean, that's mainly through direct emissions. So, a lot of people know about cows burping, that's one of the biggest source of emissions, but also through land use change, things like cutting down rainforests to grow crops to feed cattle and other animals, that also contributes to global greenhouse gas emissions.

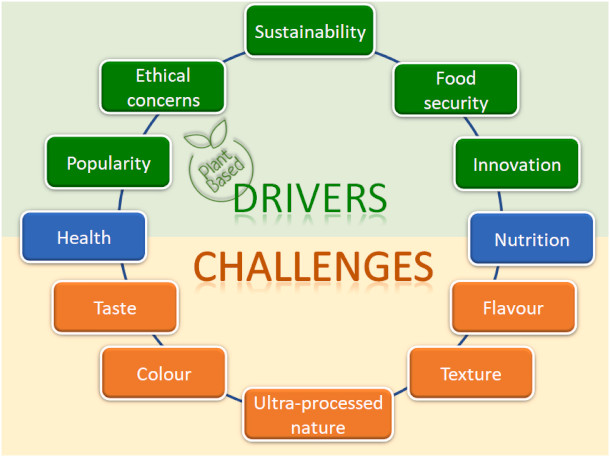

In order to reduce meat consumption on a larger scale, there are different factors that need to be considered to promote the shift. (Photo: Abdo Hassoun, Wikimedia Commons, BY CC 4.0)

BELTRAN: Why do you think the carbon emissions from food, agriculture, and in particular, meat production, are rarely discussed in US media, despite significant evidence of their impact?

MCBEY: I think that's a very good question, and I have theories about why it might be. I think one of the reasons is that telling people what to eat in general is quite a hard sell. It's something that not a lot of people want to hear. So there could be sort of sensitivities around, we don't really want to put that message out there, we don't want to really be associated with that. I think also perhaps the way that the news desk work, the food section might be siloed from the environment section, so that there's not that kind of crossover where these things are kind of discussed in the same way that there's something like plane travel, which is another big emitter. That's a lot more easier to discuss and a lot more obvious. The food system's a little bit more distant, a little bit more complex.

BELTRAN: And you know what can be done here? You know, how important do you think informational campaigns are in spreading awareness about meat consumption and its impact on climate change?

MCBEY: So I think they're necessary, but not sufficient. So information on its own doesn't tend to change behavior. So an example would be something like the Five a Day campaign in the UK, where people have been told that they should try and eat five portions of fruit or vegetables every single day. Now that was launched over 20 years ago, and its impact on fruit and vegetable consumption has been quite small. So we know that just simply telling people what they should or shouldn't do doesn't really work. You have to kind of go beyond that if you want real change. But that being said, it's important to kind of give that bedrock for why there should be a change in the first place, and it will encourage some people to act. There will be some people who will say, okay, this is a big problem. It's something I want to act on. But, even those who don't maybe act straight away, at least they've got kind of the background knowledge as to why they might be asked to make some changes. But you can also do things in what we call the food environment. So the food environment is where we interact with the food system. So it's the shops or stores where we buy food, or the restaurants. You can make small changes there that can guide people towards what might be better choices, both for their health and for the environment. So you make more sustainable choices as a default. So that if people want the meat option, they can ask for it, but by default, they might get the reduced meat or the no meat option. There are sort of simple tools like that that have been shown to work, generally in smaller scale settings, but these are the sort of things that are being scaled up more and more, both in America and also in other places around the world. So we've got sort of food suppliers and food retailers who are actively engaging with these sorts of things to try and promote healthy, sustainable options more.

Making plant-based or smaller meat portion meals more affordable and accessible could help normalize them within society. (Photo: Phat Nguy, Pexels, Pexels License)

BELTRAN: You recently put out a study titled, “Perceived Effectiveness of 25 Interventions and Policies Designed to Reduce Meat Consumption.” Can you tell us a little bit more about this study?

MCBEY: Yeah, so we were interested in what sort of things people thought could work to reduce their personal meat consumption, but we're also interested in whether that might be different for people who are really keen on reducing meat consumption versus people who really didn't want to reduce meat consumption. And we found that, we found these two groups, and then we found bigger groups in the middle. We then asked these people to rank different policies and interventions that are designed to reduce meat consumption, and these were all the way from giving people a flyer telling them why they should or shouldn't eat less meat, through to what we would call nudges, so more gentle persuasions such as making vegetarian options more visible or more easily obtainable, all the way through to more draconian measures such as taxation or banning meat products in certain places. What we found, which was quite surprising to us, is there was a lot of agreement across these different attitudinal profiles. So what they thought wouldn't work was to be told what to do, which is what we already know. But what people agreed would work is to make the vegetarian options cheaper, to make them tastier, and to give them a wider variety of things that they can choose from. Now, I would caveat that by saying that what people think will work and what actually might work could be two different things. But there is other evidence that suggests that these things that we found people thought would work are actually effective when we do tests on them.

BELTRAN: Yeah, you know, I'm wondering, to what extent is it possible to have meat continue to be a part of people's diets without it having such a drastic impact on the climate crisis?

MCBEY: So yeah, I think that's a really good question, and it's something that I come across a lot in my work. And one of the things that people always say to me is, well, I don't want to be a vegan, or I don't want to be a vegetarian. They see it very much. Is this all or nothing. And that's simply not true. We can all make small changes where either we have days where we maybe don't eat any meat, or even in the meals that we eat, we can have less meat in them. We can have what are called blended meals. So instead of a chili or a bolognese sauce being all beef, we can mix that beef with lentils or pulses, which are going to be healthier. They're going to give us more fiber, which we tend to lack, but it's also going to have an environmental impact by halving the amount of meat, let's say you're going to then half the environmental impact generally, of that meal. So it doesn't have to be an all or nothing approach, and I think that's the kind of messaging that we need. These small changes can all add up if we're all willing to kind of do our bit.

In the modern day, the world clears a soccer field’s worth of tropical forest every six seconds for agriculture use. (Photo: Kate Evans, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BELTRAN: David, you know, stepping away from your sociologist role for a moment, how do you personally think about choosing to eat meat or abstain when you consider the climate impacts?

MCBEY: Yeah, so I've been working in this area, I guess, for around about a decade now, and I think it would be impossible to kind of do this kind of work and not change the way you eat. Now, a lot of colleagues I work with do choose to follow a vegan or a vegetarian diet, and I think that's great. I personally still enjoy meat, but I enjoy it a lot less frequently than I used to maybe sort of 10 or 15 years ago, so I like to think that I still have an understanding about why people would choose to eat meat, and I know the challenges that you can face. I've also got three young children, and two of them are old enough so that they can tell me what they do like to eat and what they don't like to eat. Getting vegetables into my daughter especially is a daily challenge. Creating meals where she can have the taste of meat sometimes, but there's also lots of vegetables hidden in there, I find that she can enjoy them too. So again, there's not gonna be a one size fits all, I don't think for every single person or every single family, and the way that we found to do it is simply by blending our meals more, but then also having meat-free days as well. Because actually, we do eat quite a lot of vegetarian meals all the time without probably labeling them as such. So a lot of pasta meals don't contain any meat, and people kind of regularly eat them. So it's as much a mindset as anything else. Just about thinking that, yeah, I'm not a vegan, I'm not a vegetarian. I perhaps never will be. But I like to think that I do my bit by just not eating too much meat, not eating excessively.

David McBey is a behavioral scientist focused on diet-climate links at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. (Photo: Courtesy of David McBey)

BELTRAN: I guess not everyone you know loves haggis. How does your daughter feel about haggis?

MCBEY: Oh, that's a good question. So my son loves haggis because he loves all these kind of traditional Scottish foods. And my daughter, I think she would probably try it and screw up her face, but it's not something we eat too often, because we only tend to eat it maybe once or twice a year on special occasions. Personally, I love it, and I guess that is something that I would struggle to give up, because it is a part of our food culture here in Scotland, it's a symbolic meal, and I've got lots of fond memories about eating haggis with my family, with my grandparents. And I think to ask people to give up those kind of memories is quite difficult because, because food isn't just sustenance, there's a whole kind of culture and a whole kind of social ability around it. And I think it's important to remember that when we're asking people to make changes.

BELTRAN: David McBey is a behavioral scientist focused on diet climate links at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. Thank you so much for joining us.

MCBEY: Thank you very much. It's been my pleasure.

Related links:

- The Guardian | “Meat Is a Leading Emissions Source – but Few Outlets Report on It, Analysis Finds”

- More about Dr. David McBey

[MUSIC: Elephant Sessions, “Colours” on What Makes You, Elephant Sessions]

Overseas Chinese Mining and Spills

A landscape in Zambia 12 weeks after a Chinese copper mine spilled toxic waste laced with heavy metals, including lead, arsenic and uranium. (Photo Katie Surma, Inside Climate News)

DOERING: In 2013 China launched a global infrastructure and economic development project known as the Belt and Road Initiative. So far it has invested over $1 trillion in overseas infrastructure for projects like railways, dams and ports, as well as mining in developing countries around the world. Now, as China becomes a clean energy leader producing more solar and wind than the rest of the world combined, it needs more raw materials than ever. But extracting those materials needed for clean energy, especially metals, can come at a heavy environmental cost. Katie Surma is a reporter with our media partner Inside Climate News, and as part of their global series “Planet China,” she’s been looking at the impact of these projects in Africa. Katie, welcome back to Living on Earth!

SURMA: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

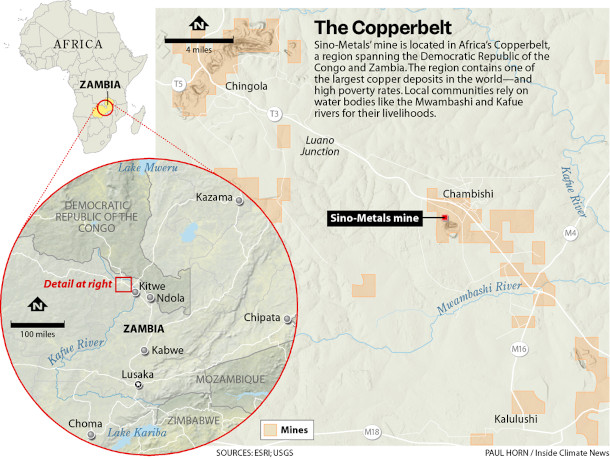

DOERING: So let's focus in on one particular part of the world where this is happening. You've been writing about environmental impacts from Belt and Road copper mining in the copper belt, this is a copper rich region across Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo. So what exactly is happening there in Zambia?

SURMA: Well, so we went up to look at a copper mine that's run by a state-owned Chinese company called Sino metals and in February, this company's, it's called a tailings dam, where it stores all of its mining waste, like huge sort of slag mountains with pools of millions of gallons of toxic waste, burst and flooded into local villages and riverways throughout the country. And so we went up to look at the impacts of that, but the region, more broadly, is just riddled with mining activity, both in Zambia and across the border in the DRC.

An infographic depicts Africa’s Copperbelt region. It shows the location of the Sino-Metals mine near to local waterways like the Mwambashi and Kafue rivers. (Photo: Paul Horn, Inside Climate News)

DOERING: So when this tailings dam burst, what happened with this like copper slurry going out into the surrounding area? And why was this dangerous for communities?

SURMA: Yeah, well, the villages that we talked to that were affected, the villagers, they said it sounded like a waterfall coming at them. You know, the tailings waste is acidic for one, so when the water was tested, you know, like river ways were tested after the spill, the pH in some areas was one, which is a level known to dissolve human bone, yeah.

DOERING: Wow. That's such a low pH, it's really acidic.

SURMA: Right? Yeah, exactly. And then, you know, it's also laced with heavy metals, arsenic, lead, uranium, so really dangerous stuff. You know, heavy metals don't dissolve in nature, they have to be physically removed. That's why tailings dams are supposed to be built to last 10,000 years. You know, mining sometimes gets a bit of a pass from environmentalists because it's mining green, so called green minerals for renewable energies in some cases, but the waste that comes out is really dangerous, and so the people living in the villages we went to, these are folks who rely on farming, both for their income and also it's what they eat. When they don't have money to buy other food, they survive on what they grow, and when the waste washed through, their livelihoods were done. I mean, they can't eat, they don't have any other way to make money, and their water sources are entirely contaminated. So what the company's been doing is bringing them like little packs, 300 milliliter packs of water to use and they're supposed to survive on that. But the spill has been absolutely devastating. And then, you know, that's just the immediate impact on the villages. I mean, this stuff has gotten into the waterways and washed far throughout the country.

Boniface Sichalwe walks through an area where millions of liters of toxic mining waste spilled earlier. Sichalwe’s farm was completely decimated. (Photo: Katie Surma, Inside Climate News)

DOERING: Wow and yeah, I mean, it impacts this year's growing cycle, if they're making a livelihood from growing crops. But also, like, unless this stuff is cleaned up, years into the future, I can imagine.

SURMA: Yeah, that's right. And I asked people, do you know what's going to happen? People are fearful about the future, and they just don't know and there's a whole reason for why they don't know. Civil society workers and even these folks' lawyers have had trouble getting in to talk to them. The mine's position is that at least this one community is on the mine's land, and so they have restricted people from coming in. There's a lot of confusion, a lot of fear, like I said, about the future, not knowing what will happen, not knowing if they'll have new land or if they'll be able to farm their old land again.

DOERING: And I think you talk to a farmer who usually makes about $1,800 or so a year from what he's able to grow on his land, and he is seeing none of that this year, and the money from the company has not nearly been enough.

Boniface Sichalwe holds a used 300 milliliter water bag. The Chinese mining company Sino-Metals Leach Zambia has been distributing the water packets after the company’s toxic waste spill contaminated locals’ water supply. (Photo: Katie Surma, Inside Climate News)

SURMA: Yeah, that's exactly right, Bonifast. You know, in a typical yield of harvest, he said he'd make about 1,800 US dollars. And one of the things that was really heartbreaking about his story, and just all of this, is the year before, Zambia has had a horrible drought, a climate, you know, induced drought, people starved, and folks lost their yield that year. And so this year, they thought, we're having rain, things will be good. And then this tailing dam burst hit, and they lost everything again. And the compensation payments, what folks civil society people have told me, they range from 17 US dollars to 2,000, they're meant to be interim payments. But I mean, people were saying, like, "how are we supposed to survive?"

DOERING: And meanwhile, to receive those payments, you also just wrote about how people were asked to sign away their rights.

SURMA: Yes, so I received from a source, one of these settlement and release agreements that Sino metals, the company had locals sign before they got their compensation payments. These were compensation payments that the Zambian government ordered Sino Metals to make. And the government has not given me a response or a comment on this, but the text of these settlement and release agreements says that the payment recipient waives all their rights to sue Sino Medals, essentially. And there's two sort of burgeoning lawsuits on the horizon that would collectively demand, I think it's $420 million for emergency funds and $90 billion for a longer term cleanup fund. This is not unusual, right? With tailings dam spills, these are so pervasive that they are in the tens of billions of dollars on magnitude of cleanup. And so, I mean, the company will use these agreements it got to try to shield itself. And it's worth noting too that a lot of these villagers can't read, they also didn't have access to lawyers because they were restricted from talking to their lawyers by the company.

A home just outside of the Kalusale community in Zambia’s Copperbelt. (Photo Katie Surma, Inside Climate News)

DOERING: Yeah, you know, we're really facing an existential crisis when it comes to climate change, and the clean energy transition is vital to reducing emissions. But what does this transition really mean for local communities who are exposed to extractive mining industries?

SURMA: Yeah, I think that's a great question. I mean, I think the starting place is acknowledging that climate change has to be addressed. We're breaching limits that scientists have said keep us within a safe operating space for humans. That being said, you know, by just saying we need to deploy more renewable energy without addressing those deeper justice issues, that's, it's not a solution. When I talk to sources in South America or Africa, they see the global north's energy transition as green colonialism and beyond the pollution, mining also is dangerous in terms of environmental defenders, people who try to defend their territories to protect it from harm. And I think the latest numbers are something like 320 human rights defenders are killed every year, and most of them are environmental defenders. One source said, people here die so that people in your country can drive electric SUVs. Just think we have to grapple with these difficult issues. It's a really hard problem to solve, but I don't think you know it serves us to not recognize these justice issues.

DOERING: Katie Surma is a reporter at Inside Climate News, covering the rights of nature movement and international environmental justice. Thank you so much, Katie.

SURMA: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Inside Climate | “Chinese Mining Firm Downplays Toxic Waste Spill as Residents Reel From Impacts”

- Inside Climate News | “The Woman Holding Chinese Mining Giants Accountable”

- Inside Climate News | “Zambia Ordered a Mining Company to Pay Villagers After a Toxic Waste Spill. The Firm Made Them Sign Away Their Rights First”

[MUSIC: Em9, “Ngulube” Single, Chill Ghost]

BELTRAN: Just ahead, LA fire survivors can choose to rebuild with fire-resistant materials, but it’s gonna cost you. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the estate of Rosamund Stone Zander - celebrated painter, environmentalist, and author of The Art of Possibility – who inspired others to see the profound interconnectedness of all living things, and to act with courage and creativity on behalf of our planet. Support also comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Em9, “Ngulube” Single, Chill Ghost]

Rebuilding Back Better After Wildfire

Small model of the proposed design for David’s new home created by JacobsChang Architecture. (Photo: David Brancaccio)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

David Brancaccio, who you may know as the host of Marketplace Morning Report, is no stranger to climate disruption. He lost his home in the devastating Los Angeles fires this past January only two months after moving in. Back then, Living on Earth host Steve Curwood talked with David as shock rippled through his community of Altadena. It’s now October, and while the fires may have disappeared from the headlines, many neighborhoods like David’s are still trying to piece themselves back together. Steve Curwood checked in with David Brancaccio to see how he and Altadena are faring.

CURWOOD: So David, it's been nine months since the fires, and eight months since we last talked to you. How you holding up, how you feeling?

BRANCACCIO: We're doing okay. I worry about the neighbors. I really do. On my single block, just one street, by my count, 21 houses burned completely, and people were in different stages of their financial lives and just where they were in their lives when the fire happened, and so they're able to move forward at different rates. Some on the street are actually selling their property. They're getting out. The decision that Mary Brancaccio and I have made is to if it is at all possible, we're really giving it the old college try, we have very firm plans to rebuild on that property, and so fits and starts, not quite sure if it's all coming together, but we're trying.

David Brancaccio (center) at Pasadena Playhouse Roundtable on July 24. David talks with students from the USC Annenberg Center on Communication and Leadership Policy Wildfire Youth Media Initiative. (Photo: USC Annenberg Wildfire Youth Media Initiative)

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the community there, this block where your house is. I mean, how are local businesses doing? Are people gathering? Are they communicating with each other? What's going on?

BRANCACCIO: There are good things and bad things. The good things are, you get to know people. I was fairly new in that community, right? We met the neighbors really fast. We have a wonderful WhatsApp group just for the block, run by a very committed neighbor named Ellen, and there's a party in just a few weeks on a Sunday. Everyone who's willing and able is going to show up. It'll be a bit of a working party for me. I'm going to go with the tape recorder. I think that's what I'm going to do on the one-year anniversary on my program is just, one year later, how are the people on one block faring? The house that we lost was a cutesy English Tudor-y thing.

David and Mary Brancaccio’s home before the January 2025 LA fires. (Photo: David Brancaccio)

There were almost 200 of those houses in the Altadena area, Jane's cottages. That's a group that has had some social gatherings and the exchange of information. There is something called the Altadena Collective, and it's quite a formal organization where they've vetted some contractors. They've had contractors come in and share what their prices would be and their approach, and then pro architects, who also lost houses in the group, evaluate those for us. We don't have to use those contractors, but what if we could even rally together in the Altadena collective and all buy our class one fire resistant roof shingles as a group, right? We could probably save some money. So that's the good part. The bad part is, it's really sobering. Steve, it really came home to me a few weeks ago, USC, they did a program with high school students, nine from the Palisades fire, nine from the Altadena, Pasadena area. They brought in high school students this summer. I helped a little bit to do a reporting project. It was like oral history. And during the roundtable discussions, they were sort of in a positive way, building on the conversation, looking at the positive side of this, that this kind of adversity breeds character kind of statements. Then this one young man, I forget his first name, I'm sorry, from Altadena, said, look, it's important to keep moving forward in a positive way. But can I just say? He said, this stinks. This is terrible. He said he had just gone back to his family's property for the first time after the fire earlier in the day, and all he wanted to do was pick up his phone and text his friends to come over, maybe give him some support, or just be there, maybe have some fun where they used to have fun. He said, there's no one who lives here who could come. Everyone is dispersed. So, you know, forget about the houses, forget about the trees. This guy has lost community.

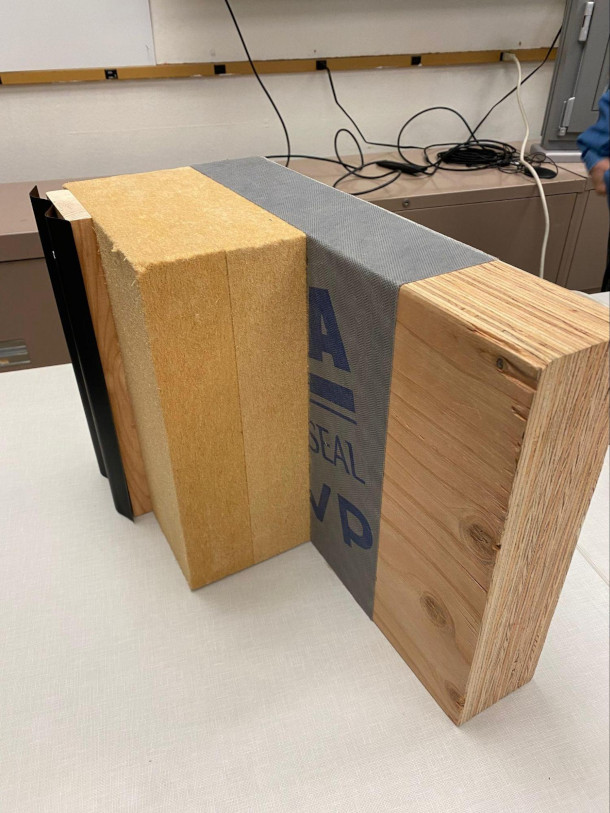

Test assembly of a piece of Cross Laminated Timber (right) attached to wood pulp insulation and an outer layer of corrugated metal exterior, School of Architecture and Environment, University of Oregon, Eugene. (Photo: David Brancaccio)

CURWOOD: Now what about the Brancaccios? You're one of those doggone it, we're going to rebuild here. I imagine you'll do it a bit differently this time around. Talk to me about the designs that you have in mind.

BRANCACCIO: Yeah. So it was a 99-year old house that burned. It was so perfect and precious in every way. It's devastating to lose it, but we don't want to rebuild it just like that. We have to think about fire hardiness. It is a new 100 years. So we're doing what we can, given the fact that I work for a nonprofit and I'm not independently wealthy, okay? It is said that the most sustainable way I could rebuild this house is what we're trying if we can afford it. Big in Europe, big in the Pacific Northwest. It's called cross laminated timber. You may have talked about mass timber on this program over the years. It looks like six-inch-thick butcher block. In a fire, they're quite hardy. They're better than steel, tests show. When you put 2000 degrees of flame on these things, they blacken with soot, and the soot becomes a barrier layer, and it doesn't burn through. You'd have to fix it. You’d probably have to replace the panel, but hopefully it would keep the fire from entering the interior of the house.

Mary Brancaccio consults with a contractor with the Army Corps of Engineers during the clearing of debris from the property, April 7, 2025. (Photo: David Brancaccio)

The panels will face in, so there's not much drywall to be imported from Mexico, probably with the tariff. We'll see natural wood. It's supposed to smell like wood, mineral wool insulation on the outside, and then concrete stucco over that, so it'll look like a normal stucco California house on the outside is the plan. We're hoping for a raised seam metal roof. We don't have eaves that can catch embers. It's still small. That's one of our biggest nods to sustainability. And here's the problem: it's more expensive than studs and plywood, so you have to hope that you can find a building contractor here in Southern California who recognizes that they'll use less labor putting it up. It's supposed to take like three humans and a little crane thing. The thing that keeps us awake at night as we speak, is the following: in about a week, two weeks, soon, four contractors will tell me how much they think it costs. We're budgeted for ridiculous, but we're not budgeted for off the charts stupid in terms of price. We are paying, he said, with resignation, a lot of money for the windows. We're tempering everything, and it's dual pane everything. The old windows from 1926 were single pane, and that's supposed to give you a decent shot at fire resistance. The landscaping will be hardscape mostly. We will have some desert succulents, but we're not going to have stuff that catches fire near the house. It's all electric, is the plan for the house. No gas service. So we're trying.

View from neighbor’s property on the day debris was removed by Army Corps of Engineers contractors, April 7, 2025. (Photo: David Brancaccio)

CURWOOD: Well and remember, those windows are going to really keep the hot, hot heat out and the heat that you want, or the cooling that you want, inside. So over the longer term, you'll actually save money operating a building like that compared to the 100 year old structure, which I imagine was fairly porous.

BRANCACCIO: Yeah, it's fairly porous. So, you know, it may be, I don't think it's going to be a net zero house, but we're going to get pretty close. And in California, new constructions need to have solar panels. However, the governor waived that for the fire rebuilds to lift some of the burdens on people. You have to be solar panel ready. I mean, look, would I show my face on Living on Earth if I, if I wasn't going to put solar panels on this house? I'm putting solar panels on the house, and that could reduce my electricity bill to almost nothing. So, you know, you do what you can. And I will admit this to you, Steve, there will be people listening to us feeling that I'm sounding sanctimonious about my green pedigree here. And they will say, David, if you really cared about the climate, move in with one of your kids in an existing structure.

CURWOOD: And you would say?

New growths since the fire atop a burned stand of cactus at the Brancaccio Property. (Photo: David Brancaccio)

BRANCACCIO: And I would say, well, I've asked them, nobody's raising their hands to welcome us into their midst. They also, you know, in the world of the affordability crisis, they don't have big places. But the other thing is, Altadena is our only piece of real estate, okay? And the idea that this one real asset that I own wouldn't be developed seems like poor personal finance. I wish I was the guy who could buy property and turn it into a conservancy and plant wildflowers, and maybe I'll win the lottery and do that someday. But we only got one plot of land that we own, and we're putting a house on it at this point, if we can.

CURWOOD: And what about the notion of optimism, courage in this time of, let's face it, climate change is steadily getting worse. So what does it say for you and your family to make this statement in society that doggone it, we will persevere?

Flowers flourish in the front yard of David’s burned out property. The plan after a rebuild is to have fire-resistant desert succulent plants here. (Photo: David Brancaccio)

BRANCACCIO: Yeah, at a time that some people start conversations with me about moving out of the country because of the direction of politics from their perspective, right? Here, I am, wanting to cling to real estate in California. I remember being a kid when we thought that nuclear war was going to break out at any minute. And I'm not saying the nuclear threat is in any way in retreat. It's just not top of mind the way it was. But we somehow tried to envision a better future, tried to invest in our friends, our communities, our own educations, have kids that were productive members of society one way or another, and that's how we're feeling now, which is, there was something special about Altadena. Everybody says it about the nature of community there. There is a lovely bar in Altadena that did not burn. There are two bars in Altadena that did not burn. One of them is super cool. It's run by a schoolteacher. But there's this other bar too, closer to where our property is, called Good Neighbors, and they built an external, like a patio thing that's become a community venue. They bring in food trucks, they do music. They do events. The public station in Southern California, one of them is called LAist. They had me do a community event there with some experts on fire rebuilds, and it's a real amenity that has been working very well. There is a Thai restaurant on one of the commercial boulevards, where there's still this devastation to the left and to the right, but they're doing brisk business. There is a burger joint not far away that's fantastic that's doing brisk business because I think people understand that once we rebuild our houses, we’ll want these enterprises to be still standing so we can go back to them.

CURWOOD: So David, what's the next step for rebuilding there in Altadena?

David at his old home following the January 2025 LA fires. David Brancaccio is the host of Morning Marketplace Report. (Photo: David Brancaccio)

BRANCACCIO: We got a bunch of milestones upon us. First of all, we're going to find out how much contractors want to build it and see if we have the money. Ooh! Then when are these permits going to show up? Let's say the permits show up in a couple months. We can pour a foundation. Wooden panels are supposed to show up on a truck 12 weeks after I put down a down payment on them. So am I speaking with misplaced optimism? Could we tip wooden panels up into position by Valentine's Day? Earlier? We shall see. But once those panels are up, it's only about another six months till we could move in. So I have high hopes that we'll get permits. I have high hopes we'll have the money for this, and I'll be delighted to come back and report on if it ever happened, and if ours can be built for a reasonable amount, if we can show that the economics of this work, I think it's going to produce a delightful house, and maybe other people will adopt this more sustainable technique to construction.

BELTRAN: That’s Marketplace Morning Report Host David Brancaccio, speaking with Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood. And stay tuned to Living on Earth in the coming weeks for a special episode on wildfire threats and resilience.

Related links:

- Listen to our February 2025 Conversation with David Brancaccio.

- “Architecture After the Fires” Exhibition at The Southern California Institute of Art (SCI-Arc), featuring fire-ready house models, sketches, and designs, including the Brancaccios’.

[MUSIC: The Cinematic Orchestra, “To Build A Home” on Ma Fleur, Ninja Tune under exclusive license to Domino Recording Co]

DOERING: Next time on Living on Earth, The potential link between lead exposure and serial killers.

FRASER: Of course everybody has heard of Ted Bundy, but one of the things I became really interested in was where he grew up because he was born actually in Vermont, but then as a young child moved to Tacoma, Washington. And Tacoma had both a very high crime rate, and it also had a lead smelter, which became over time a copper smelter, but it was putting out large amounts of lead and arsenic particulates into the air throughout the whole period when Ted was growing up. So he was exposed to a significant amount of these toxins. Whether that contributed to what he ended up doing, we certainly can't know, we can't prove that, but it's an interesting fact about him because he always seemed like somebody who didn't entirely seemed to have developed in a normal way. He's like many serial killers, he had fantasies of rape and murder from a very, very young age. So that was something that I was interested in looking at, especially when you see other acts of serial murder that are associated with that same area.

DOERING: The author of Murderland joins us, next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Zymphonica, “Creep – Piano & Strings Version” Single, Zymphonica]

BELTRAN: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Sophie Bokor, Daniela Faria, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jade Poli, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio, and we always welcome your feedback at comments@loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth