Media and the Meat Habit

Air Date: Week of October 24, 2025

Methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, enters the atmosphere through the digestive processes of livestock such as cows, contributing significantly to global warming. (Photo: Trougnouf, Wikimedia Commons, BY CC 4.0)

Meat is the biggest single source of carbon emissions from the food system, which is itself responsible for a third of global greenhouse gas emissions. Sociologist David McBey from the University of Aberdeen in Scotland joins Host Paloma Beltran to talk about the gap between reality and coverage of how meat contributes to global warming, as well as effective strategies for encouraging people to choose to eat less meat without trying to force them to do so.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

From Thanksgiving turkey to 4th of July hot dogs, meat is a staple in American culture. According to the USDA, the average American eats roughly 225 pounds of red meat and poultry every year, and all that meat carries a pretty hefty carbon footprint. And as economies grow, global diets are becoming more meat centric. But meat’s connection to the climate crisis is largely underreported in major news outlets. Sentient Media, a non-profit news organization focused on creating transparency around factory farming and its impact on the climate, conducted an analysis that found that 96% of climate news stories don’t cover animal agriculture as a major pollution source. To help us understand why, and what strategies might address the climate costs of our meat-eating habits, we’re joined by sociologist Dr. David McBey from the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. David, welcome to Living on Earth!

MCBEY: Thank you very much for having me.

BELTRAN: So David, tell us a little bit more about the meat industry and meat consumption. How are they major players in carbon emissions?

MCBEY: Yeah, so the entire food system is responsible for around about a third of global greenhouse gas emissions, and of that, meat is the biggest sort of single cause. I mean, that's mainly through direct emissions. So, a lot of people know about cows burping, that's one of the biggest source of emissions, but also through land use change, things like cutting down rainforests to grow crops to feed cattle and other animals, that also contributes to global greenhouse gas emissions.

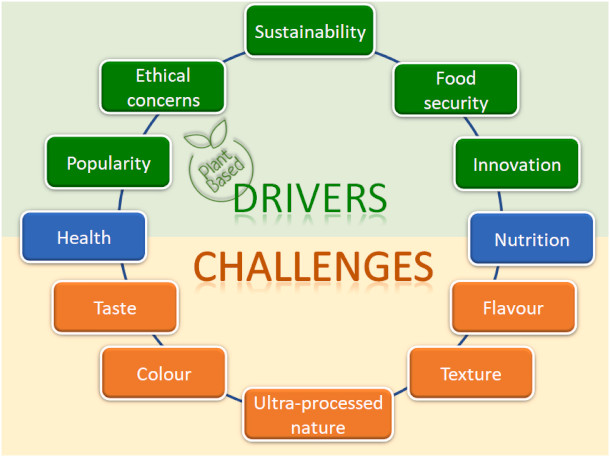

In order to reduce meat consumption on a larger scale, there are different factors that need to be considered to promote the shift. (Photo: Abdo Hassoun, Wikimedia Commons, BY CC 4.0)

BELTRAN: Why do you think the carbon emissions from food, agriculture, and in particular, meat production, are rarely discussed in US media, despite significant evidence of their impact?

MCBEY: I think that's a very good question, and I have theories about why it might be. I think one of the reasons is that telling people what to eat in general is quite a hard sell. It's something that not a lot of people want to hear. So there could be sort of sensitivities around, we don't really want to put that message out there, we don't want to really be associated with that. I think also perhaps the way that the news desk work, the food section might be siloed from the environment section, so that there's not that kind of crossover where these things are kind of discussed in the same way that there's something like plane travel, which is another big emitter. That's a lot more easier to discuss and a lot more obvious. The food system's a little bit more distant, a little bit more complex.

BELTRAN: And you know what can be done here? You know, how important do you think informational campaigns are in spreading awareness about meat consumption and its impact on climate change?

MCBEY: So I think they're necessary, but not sufficient. So information on its own doesn't tend to change behavior. So an example would be something like the Five a Day campaign in the UK, where people have been told that they should try and eat five portions of fruit or vegetables every single day. Now that was launched over 20 years ago, and its impact on fruit and vegetable consumption has been quite small. So we know that just simply telling people what they should or shouldn't do doesn't really work. You have to kind of go beyond that if you want real change. But that being said, it's important to kind of give that bedrock for why there should be a change in the first place, and it will encourage some people to act. There will be some people who will say, okay, this is a big problem. It's something I want to act on. But, even those who don't maybe act straight away, at least they've got kind of the background knowledge as to why they might be asked to make some changes. But you can also do things in what we call the food environment. So the food environment is where we interact with the food system. So it's the shops or stores where we buy food, or the restaurants. You can make small changes there that can guide people towards what might be better choices, both for their health and for the environment. So you make more sustainable choices as a default. So that if people want the meat option, they can ask for it, but by default, they might get the reduced meat or the no meat option. There are sort of simple tools like that that have been shown to work, generally in smaller scale settings, but these are the sort of things that are being scaled up more and more, both in America and also in other places around the world. So we've got sort of food suppliers and food retailers who are actively engaging with these sorts of things to try and promote healthy, sustainable options more.

Making plant-based or smaller meat portion meals more affordable and accessible could help normalize them within society. (Photo: Phat Nguy, Pexels, Pexels License)

BELTRAN: You recently put out a study titled, “Perceived Effectiveness of 25 Interventions and Policies Designed to Reduce Meat Consumption.” Can you tell us a little bit more about this study?

MCBEY: Yeah, so we were interested in what sort of things people thought could work to reduce their personal meat consumption, but we're also interested in whether that might be different for people who are really keen on reducing meat consumption versus people who really didn't want to reduce meat consumption. And we found that, we found these two groups, and then we found bigger groups in the middle. We then asked these people to rank different policies and interventions that are designed to reduce meat consumption, and these were all the way from giving people a flyer telling them why they should or shouldn't eat less meat, through to what we would call nudges, so more gentle persuasions such as making vegetarian options more visible or more easily obtainable, all the way through to more draconian measures such as taxation or banning meat products in certain places. What we found, which was quite surprising to us, is there was a lot of agreement across these different attitudinal profiles. So what they thought wouldn't work was to be told what to do, which is what we already know. But what people agreed would work is to make the vegetarian options cheaper, to make them tastier, and to give them a wider variety of things that they can choose from. Now, I would caveat that by saying that what people think will work and what actually might work could be two different things. But there is other evidence that suggests that these things that we found people thought would work are actually effective when we do tests on them.

BELTRAN: Yeah, you know, I'm wondering, to what extent is it possible to have meat continue to be a part of people's diets without it having such a drastic impact on the climate crisis?

MCBEY: So yeah, I think that's a really good question, and it's something that I come across a lot in my work. And one of the things that people always say to me is, well, I don't want to be a vegan, or I don't want to be a vegetarian. They see it very much. Is this all or nothing. And that's simply not true. We can all make small changes where either we have days where we maybe don't eat any meat, or even in the meals that we eat, we can have less meat in them. We can have what are called blended meals. So instead of a chili or a bolognese sauce being all beef, we can mix that beef with lentils or pulses, which are going to be healthier. They're going to give us more fiber, which we tend to lack, but it's also going to have an environmental impact by halving the amount of meat, let's say you're going to then half the environmental impact generally, of that meal. So it doesn't have to be an all or nothing approach, and I think that's the kind of messaging that we need. These small changes can all add up if we're all willing to kind of do our bit.

In the modern day, the world clears a soccer field’s worth of tropical forest every six seconds for agriculture use. (Photo: Kate Evans, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BELTRAN: David, you know, stepping away from your sociologist role for a moment, how do you personally think about choosing to eat meat or abstain when you consider the climate impacts?

MCBEY: Yeah, so I've been working in this area, I guess, for around about a decade now, and I think it would be impossible to kind of do this kind of work and not change the way you eat. Now, a lot of colleagues I work with do choose to follow a vegan or a vegetarian diet, and I think that's great. I personally still enjoy meat, but I enjoy it a lot less frequently than I used to maybe sort of 10 or 15 years ago, so I like to think that I still have an understanding about why people would choose to eat meat, and I know the challenges that you can face. I've also got three young children, and two of them are old enough so that they can tell me what they do like to eat and what they don't like to eat. Getting vegetables into my daughter especially is a daily challenge. Creating meals where she can have the taste of meat sometimes, but there's also lots of vegetables hidden in there, I find that she can enjoy them too. So again, there's not gonna be a one size fits all, I don't think for every single person or every single family, and the way that we found to do it is simply by blending our meals more, but then also having meat-free days as well. Because actually, we do eat quite a lot of vegetarian meals all the time without probably labeling them as such. So a lot of pasta meals don't contain any meat, and people kind of regularly eat them. So it's as much a mindset as anything else. Just about thinking that, yeah, I'm not a vegan, I'm not a vegetarian. I perhaps never will be. But I like to think that I do my bit by just not eating too much meat, not eating excessively.

David McBey is a behavioral scientist focused on diet-climate links at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. (Photo: Courtesy of David McBey)

BELTRAN: I guess not everyone you know loves haggis. How does your daughter feel about haggis?

MCBEY: Oh, that's a good question. So my son loves haggis because he loves all these kind of traditional Scottish foods. And my daughter, I think she would probably try it and screw up her face, but it's not something we eat too often, because we only tend to eat it maybe once or twice a year on special occasions. Personally, I love it, and I guess that is something that I would struggle to give up, because it is a part of our food culture here in Scotland, it's a symbolic meal, and I've got lots of fond memories about eating haggis with my family, with my grandparents. And I think to ask people to give up those kind of memories is quite difficult because, because food isn't just sustenance, there's a whole kind of culture and a whole kind of social ability around it. And I think it's important to remember that when we're asking people to make changes.

BELTRAN: David McBey is a behavioral scientist focused on diet climate links at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland. Thank you so much for joining us.

MCBEY: Thank you very much. It's been my pleasure.

Links

The Guardian | “Meat Is a Leading Emissions Source – but Few Outlets Report on It, Analysis Finds”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth