Serial Killers and Lead Exposure

Air Date: Week of October 31, 2025

Caroline Fraser’s newest book, Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers. (Photo: Courtesy of Caroline Fraser)

The Pacific Northwest of the US harbored a serial killer hotspot of sorts in the 1970s, associated with the neurotoxin lead. Seattle-born author Caroline Fraser explores this link in her book Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers. She joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss how dangerously high lead exposure from smelters and gasoline may have led to the increase of violence and murders in the region.

Transcript

DOERING: Now, serial killers may not be the type of topic you expect to hear about on Living on Earth. But hear us out, it’ll all make sense in a moment.

CURWOOD: From Ted Bundy and Jeffrey Dahmer to Charles Manson and the Zodiac Killer, serial killers are a distinctly American phenomenon. And Jenni, we have more serial killers in our history than the next ten closest countries combined.

DOERING: Oh, really? Yikes! I have heard though that within this country there’s kind of a hotspot for them.

CURWOOD: Oh yes there is or was anyway and many of these serial killers were active in the 1970s in the Pacific Northwest. Seattle-born author Caroline Fraser offers one possible explanation in her new book, Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers. She theorizes that the neurotoxin lead is key to this story. And she links dangerously high lead exposure from smelters and gasoline to the increase of violence and murders in her home state. Caroline Fraser joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

FRASER: Thank you, thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: You know, in some respects, this is an autobiography, and you provide some rather intimate details of your life, like juggling two boyfriends.

The 1970s marked a time of economic uncertainty and an uptick in violence in the Seattle area where author Caroline Fraser was growing up at the time. (Photo: Seattle Municipal Archives, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

FRASER: Yeah, this book covers a period of time when I was much younger. It was the, you know, 1960s, 70s, and I really wanted to give readers who may not be familiar with that era a kind of flavor of what it was like to be a young person then, to be a young woman in particular, and what it was like growing up in an era when all these serial killings started happening.

CURWOOD: So of course, aside from your own story, this book is about serial killers and the neurotoxin lead, as well as questionable development and even geological damage. So how did the idea for Murderland first come about with all those elements?

FRASER: Well, in the Northwest, where I'm from, of course, the question has always been raised year after year, of why Seattle and the Northwest in particular seemed to be kind of a hot spot for serial killers. And of course, the newspapers were very fond of this topic, you know, and constantly were talking about, what is it about this place? And people had all kinds of theories, you know, it was the weather or the rain, or maybe it was just too gloomy a place. Maybe it was the highway system. So I'm pointing at another kind of theory to address why this might have happened, and I also am hoping that no matter what you think of this theory, whether you agree or don't agree, you may learn something about the ecological history and the environmental damage that happened in this place over the past 100 years or so.

One of the most infamous serial killers in American history is Ted Bundy, who grew up in Tacoma, Washington, not far from Fraser’s childhood home. (Photo: Florida Department of Corrections, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: The book itself, I think, opens in your hometown of Seattle in the 60s. Just set the stage for us for a moment. What was going on at that time?

FRASER: Yeah, Seattle has always had a very up and down, hot and cold economy. So the 1970s for example, was a recession. A lot of contracts were canceled at Boeing. People weren't building as many houses. People were losing their jobs, and gasoline had become very scarce and expensive. So it was a troubled time nationally and regionally for Seattle, and that was the time when I was growing up there and all these bizarre things started happening. You know, the country nationally saw a real rise in violent crime, and so did the greater Seattle area.

CURWOOD: Your book also links exposure to pollutants such as lead to the abnormally high level of crime, including serial killers in the Northwest. Let's focus for a moment on Ted Bundy, a famous serial killer. He grew up in the Tacoma area, not so many miles from where you grew up. Talk us through the connection between Ted Bundy's exposure to lead and his rise as one of America's most infamous serial killers.

The American Smelting and Refining Company, or Asarco, owned the smelter in Tacoma, which emitted dangerous levels of lead, arsenic, and other toxins. Above, a 1972 photograph of the smelter towering over a nearby home. (Photo: Gene Daniels, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

FRASER: Well, yeah, I mean, when I was 13, when he began this kind of spate of abductions and rapes and murders, nobody had really heard of the term serial killer. It's not that they hadn't existed. I mean, there have always been people like Jack the Ripper, for example, but the whole phenomenon of serial killers did not yet exist in the way that we know it now, both from the media, from Hollywood, from books, etc. So it was really kind of an unknown thing. Now, of course, everybody has heard of Ted Bundy, but one of the things I became really interested in was where he grew up, because he was born, actually in Vermont, but then as a young child, moved to Tacoma, Washington. And Tacoma had both a very high crime rate, and it also had a lead smelter. It was putting out large amounts of lead and arsenic particulates into the air throughout the whole period when Ted was growing up. And we now know, thanks to research and mapping that's been done, exactly how much lead was in Ted Bundy's front yard and his backyard. We know how much arsenic was there. So he was exposed to a significant amount of these toxins. Whether that contributed to what he ended up doing, we certainly can't know, we can't prove that. But it's an interesting fact, because he always seemed like somebody who didn't entirely seem to have developed in a normal way. Like many serial killers, he had fantasies of rape and murder from a very, very young age. So that was something that I was interested in looking at, especially when you see other acts of serial murder that are associated with that same area.

CURWOOD: And by the way, Ted Bundy was born, as you write in your book, to an unwed mother. That mother had been exposed to lead as well, given her family's business.

Otherwise known as “The Night Stalker,” Richard Ramirez was a serial killer who grew up in El Paso, Texas, home to another Asarco smelter. (Photo: Iris Schneider, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

FRASER: Yeah, that's very true. Ted Bundy's mother grew up in Philadelphia, which has been called the city of smelters because there was so much smelting activity going on there in the run up to World War II, and throughout World War II. And of course, Ted Bundy is born in 1946 just after the end of the war. There are several of these killers who I write about who really were exposed in multiple ways to lead throughout their lives, both as children and as adults, and I think it is a fair question to ask what that might have resulted in.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about how the stories of the other serial killers are linked to Bundy, the geography and the exposure to the neurotoxin: lead.

FRASER: Well, one of the other killers who I talk about is Gary Ridgway, who also grew up in the Seattle, Tacoma area, and as a child, used to play, according to his brother, in piles of copper tailings, which are the leftover rocks from mining, which themselves contain significant amounts of the kind of toxins that you see coming out of smelters. He grew up near an airport at a time when a lot of general aviation aircraft were using leaded fuel. And as an adult, he worked painting the cabs of trucks, which was at the time using leaded paint. So he's exposed to lead throughout his entire life, and I think he makes a really interesting example of this kind of exposure. Another killer is Richard Ramirez, who grew up in El Paso, Texas, where the company that owned the smelter in Tacoma had another smelter. This was Asarco, the American smelting and Refining Company. So El Paso had been the recipient of the fallout from that smelter for many, many years. And Richard Ramirez, too shows a lot of developmental difficulties as a child, somebody who had seizures and developed a very, very kind of violent fantasy life as a kid, which then he acted upon some years later as a young man in Los Angeles. But I thought it was fascinating that although we know Richard Ramirez from what he did in LA, he really grew up in a completely different place and was exposed to lead.

The EPA began to phase out leaded gas in the 1970s after evidence of severe public health impacts linked to lead poisoning came to light. Children were especially vulnerable, suffering developmental problems, low IQ, and behavioral issues. (Photo: Joe Mabel, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: So talk to me about the gender connection here to serial killers, I think the numbers that you said is less than 8% are women, almost always men. Why do you think that is and how might that be related to their exposure to lead in childhood and adulthood?

FRASER: Yeah, there have been some studies on this that show that the development of the male brain is affected much more grievously, I think, than the development of the female brain in childhood, if you're exposed to lead. The development of parts of the brain like the frontal cortex, where you have a lot of the parts of the brain that control impulsivity and aggression, and they've shown this through brain scans of people who've been exposed to lead, and the effects are much more notable in men than in women.

CURWOOD: Let's talk for a moment about the Cincinnati Lead Studies. What were the findings of that research, and why are they still relatively unknown?

FRASER: Yeah, that's a great question as to why they're not as widely known as they should be. But yes, the Cincinnati studies were a very long term series of studies that looked at kids who were exposed to varying amounts of lead and then followed them until they became young adults. The findings, I think, fairly strongly, showed a correlation between lead exposure in children and in pregnant women and the behavior of these kids after they grew up in the, you know, teen years, in the early 20s, when most violent crime is committed. There was a real strong suggestion that lead was responsible, to some extent, for a rise in violent behavior and impulsivity, in heightened aggression, in juvenile delinquency. So it's a very important series of studies. I'm not sure why it hasn't received as much attention as it should have, but I suspect a lot of that had to do with the ways in which the lead industry itself was dedicated to convincing people that lead was safe and that this was really merely a correlation, that it wasn't something that we should be concerned about. I mean, they were dedicated for years to covering up the actual information and studies that showed that lead is not safe and that there's no amount of lead that is safe in the human body.

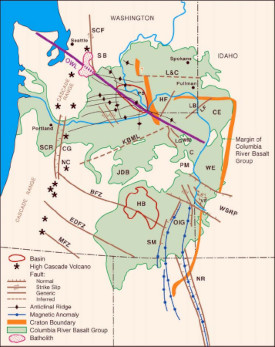

The Olympic-Wallowa Lineament, shown above in purple, is a geologic fault line that runs diagonally through the Pacific Northwest. Fraser warns that the OWL could contribute to a major earthquake in the Seattle area at any moment. (Photo: B. S. Martin, H. L. Petcovic, S. P. Reide; Wikimedia Commons; Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So what does the removal of lead from gasoline tell us about lead and violent crime?

FRASER: Well, the fascinating thing about the correlation between leaded gas and violent crime is that you see a very sharp rise in violent crime in the 1970s, it was over 10 per 100,000 people, and we'd never in the records of the FBI, we had never reached that before. And that correlates with the post World War II boom in people driving, which begins in the 1950s, you know, people are buying more cars and commuting longer distances. There's more leaded gas entering the atmosphere. So, you know, we talked about the Cincinnati studies that showed that children exposed to lead may develop heightened aggression 20 years later. So that's what you're seeing. You're seeing 1950s the amount of leaded gas is really increasing in the atmosphere. Then when these kids become around the age of 20 in the 1970s, 20, 25, you see the rate of crime rising in the 70s and 80s, and continuing through the early 90s. And what happens during that period is that, you know, we have the Clean Air Act. We have the EPA being established. We have regulations that are beginning to come in to affect leaded gasoline, and then you see a very sharp drop off beginning to happen with violent crime.

In recent decades, people have moved in high densities to cities that are vulnerable to earthquakes, including Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Above, a street market in San Francisco after an earthquake in 1906. (Photo: National Archives, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

[MUSIC: Alice In Chains, “Rotten Apple” on Jar Of Flies, Sony Music Entertainment Inc.]

CURWOOD: Just ahead, We’ll continue our conversation with Caroline Fraser about her book Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Waverley Street Foundation, working to cultivate a healing planet with community-led programs for better food, healthy farmlands, and smarter building, energy and businesses.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The LoFi Bear, “Main Title” Single, The LoFi Bear]

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Caroline Fraser’s book Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers has a deeper theme than a set of mere murder mysteries. A key part of her book considers how our society tends to ignore and deny the science of major risks such as lead exposure. So Murderland includes the story of the Olympic-Wallowa Lineament, or OWL, a geological fault line that runs through the Northwest. Caroline, you write that the land on top of the OWL is prone to floods, earthquakes, tsunamis, and other disasters, and yet we build on it anyways. Please tell us about OWL, and how it fits into your narrative...

Fraser blames large corporations, such as Asarco, for purposely concealing the alarming health consequences of their industry from the public. Above, an Asarco site in Garfield, Utah in 1942. (Photo: Andreas Feininger, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

FRASER: Yeah, the OWL is another image that I kind of fell in love with. It cropped up when a map maker, a cartographer, was drawing a map of Washington State. And this map was so detailed, and when he'd finished it, he kind of glanced across it and noticed that there seemed to be a kind of a trough that was created, sort of a weird visible line from the tip of Northwestern Washington down through the state. And he wondered what that was. He thought it probably had something to do with an earthquake fault, which is, I think, the leading theory now, but I loved the image of it and the metaphor that it makes because it suggests both the hazards of the natural world, you know, earthquake faults, and the hazards that we put ourselves in by being drawn to the places where these hazards exist. I mean, we have now moved in such large numbers and such density to places like Seattle and San Francisco and Los Angeles, where there are these earthquake faults. I think this is again a metaphor for what we do to ourselves, and both the beauty of the region and the dangers that it poses.

CURWOOD: I think in geologic history, there was a major kind of earthquake in that area, maybe some 300 years ago that killed a lot of people.

FRASER: Yes, in the 1700s, and you see fascinating records of this in Native American culture, in stories, in art and memory. And that's just a kind of fascinating record of what we're up against, because they believe that those fault lines and the Juan de Fuca plate that is being forced under the continent of North America, that that's going to cause another major earthquake of that same strength anytime now or in the future. And that's quite alarming, given that now there are so many more people and bridges and tunnels and skyscrapers and all of the things we bring along with us.

CURWOOD: And you don't live in the Seattle area any longer.

FRASER: No, no I don't.

CURWOOD: So there seems to be a theme of scientific denial throughout this story. The proximity of danger caused by this OWL fault line and the smelters is just largely ignored by the public. Why do you think that is?

Caroline Fraser is a Pulitzer Prize-winning author of four nonfiction books. She grew up in Seattle and currently resides in New Mexico. (Photo: Courtesy of Caroline Fraser)

FRASER: Yeah, I don't think we're very good at planning far into the future, even when we know about things like the earthquake faults. I mean, we now know so much more about that history than we did even 20, 30 years ago. But we still have a very hard time preparing for things like that. I mean, you see this in the government preparations for pandemics and so forth. It's, it’s very hard to get people to invest money and time in things that don't seem to be an immediate problem. And I think people just don't like to think about it. They don't like to think about the ramifications of what might happen, you know, of what could be waiting for us. So I think as human beings, we just come with some inherent limitations. You know that that keep us from doing things that are in our best interests. But obviously there are enormous stakes too, financially. I mean, for decades, it was very hard to get the smelter companies, for example, to deal with anything that they were putting into the air. They didn't even want to release any of the information they had. The system is really broken, I think, in terms of we just wait until these corporations have done the worst that they can do, and only then do we go after them to clean it up. So I think until we develop some kind of system that puts the onus on the corporations to begin with, we're really just going to always be behind the eight ball.

CURWOOD: Some would say that applies to the climate emergency as well.

FRASER: Absolutely. You know, if you look at what Exxon and Standard Oil and so many of these corporations have done, they knew about this. They knew about it for decades and lied about it, which is exactly what the smelters did. So when you're trapped in that kind of reality, I think you have to ask yourself, do we need to really reform the system from the ground up? And we do, but it's increasingly difficult to see how to make those kinds of changes.

CURWOOD: And before you go, to what extent does this book scratch the itch that you had going back many, many years, when you were living in a community where there was a lot of fear about serial killers?

FRASER: Yeah, I think that it was an enormously sort of fascinating thing for me to be able to confront some of these stories, some of these theories, and try to make some sense out of it. Whether, you know, you believe the theory or not, I think there's a whole history of environmental damage that was perpetrated on the Northwest, a place that I love dearly, and on many other places around the American West and in the United States during that era. And the history is important, whether you care about the serial killer angle or not. It's a really troubling and important history that I think if we understand it, it might help us make better decisions in the future.

CURWOOD: Caroline Fraser's book is titled "Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers." Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

FRASER: Oh, thank you. It's been a great conversation.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth