October 31, 2025

Air Date: October 31, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Climate Monster in the Caribbean

View the page for this story

Hurricane Melissa, the strongest storm to hit the Caribbean in modern times, left a wake of destruction in Jamaica, Cuba and Haiti that will take years to recover from. Jamaican climate physics professor Tannecia Stephenson describes the toll of this climate catastrophe, and meteorologist Ryan Truchelut of the consulting firm Weather Tiger joins Host Jenni Doering to explain how the storm grew so ferocious in the blink of a hurricane’s eye. (09:17)

Gwich'in People Resist Arctic Drilling

View the page for this story

The fossil fuel industry has sought drilling for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge for decades and a recent Trump administration order brings the renewed threat of oil extraction in ANWR. But Gwich’in Alaska Natives, which consider the land sacred and local Porcupine Caribou as relatives, are expressing alarm at how drilling in this fragile environment could upend their world. Kristen Moreland, Executive Director of the Gwich’in Steering Committee, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss. (08:46)

Serial Killers and Lead Exposure

View the page for this story

The Pacific Northwest of the US harbored a serial killer hotspot of sorts in the 1970s, associated with the neurotoxin lead. Seattle-born author Caroline Fraser explores this link in her book Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers. She joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss how dangerously high lead exposure from smelters and gasoline may have led to the increase of violence and murders in the region. (21:31)

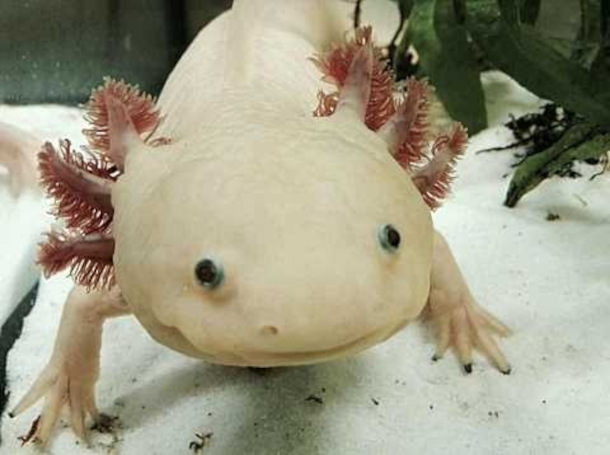

Science Note: Axolotls Released to Wild

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

Axolotls, aquatic salamanders with feathery gills that look like they’re always smiling, are endemic to a single lake in Mexico and critically endangered in the wild. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman reports on a successful release of captive-bred axolotls into wetlands that provides hope for boosting this unique creature’s wild population. (01:52)

The Many Layers of Dia de los Muertos Altars

/ Paloma BeltranView the page for this story

At the start of November, on the Day of the Dead or Dia de los Muertos, families in Mexico and beyond gather around altars to celebrate and invite back the spirits of loved ones who have passed away. Living on Earth Producer Paloma Beltran explains the symbolic meaning of altar materials and how this yearly tradition took on a new dimension for her this year. (05:02)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

251031 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Caroline Fraser, Kristen Moreland, Ryan Truchelut

REPORTERS: Don Lyman

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The Gwich’in face another round in the forty-year fight to protect caribou and their homeland in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

MORELAND: Our elders call our land Iizhik Gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit, which means the sacred place where life begins.

CURWOOD: Also, the potential link between lead exposure and serial killers.

FRASER: Of course everybody has heard of Ted Bundy. He, as a young child, moved to Tacoma, and Tacoma had a lead smelter that was putting out large amounts of lead and arsenic into the air throughout the whole period when Ted was growing up.

CURWOOD: And Hurricane Melissa gave Jamaica and Cuba a long road ahead. That's this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Climate Monster in the Caribbean

Satellite images track the moment Hurricane Melissa made landfall in the southwestern region of Jamaica. One of the most affected communities is Black River, where almost every home suffered damage and approximately 90% lost their roofs. Prime Minister Andrew Holness referred to this area as 'ground zero.' As of October 31st, an official death toll has not yet been announced. (Photo: CSU/CIRA & NOAA)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

It will take years before the parts of Jamaica, Haiti and Cuba that were hit hardest by the deadly Hurricane Melissa will recover. The strongest storm to hit the Caribbean in modern times, the category 5 cyclone came ashore in the southwest of Jamaica at 185 miles per hour, shredding just about everything in its direct path.

CURWOOD: Tannecia Stephenson is a climate physics professor at the University of the West Indies in Jamaica. She says seeing the aftermath of the storm is heartbreaking and sobering.

STEPHENSON: One of the, the main areas of impact was a parish called St. Elizabeth and for Jamaica, that's what we call our, the Breadbasket of Jamaica. A number of agricultural activities happen within that parish and sustain us as a country, and they were hit immensely.

DOERING: Black River and Montego Bay were among the places hit directly by the storm, but just about the whole island lost power and has yet to dry out from the torrential rains.

CURWOOD: And the damages from the catastrophic storm and the costs of recovery are estimated in the billions of dollars.

STEPHENSON: You know, as a small island within the Caribbean, you're between a rock and a hard place in terms of how does an island prepare for a category five storm? Immense preparations went in at government levels, organizational levels. The levels of individuals. And when you see our southwestern parishes and the impact of this storm, you know, one has to wonder, how do small islands contend with stronger storms under warmer climate? And this begs for and pushes the advocacy that is underway by small islands to say, listen, globally, we have to treat with more urgently our greenhouse gas emissions and the impacts of a warmer climate globally.

Destruction near Black River, St. Elizabeth, Jamaica. (Photo: Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

DOERING: Haiti did not suffer a direct hit from Melissa, but its intense rains are linked to dozens of deaths or missing persons there.

CURWOOD: And we have yet to get clarity about conditions in Cuba, where Melissa was still a major category three storm when it hit a city of a half million people.

DOERING: To learn more about the extreme nature of Hurricane Melissa we called up Ryan Truchelut, chief meteorologist with the consulting firm WeatherTiger. He’s based in Tallahassee, Florida. Ryan, welcome back to Living on Earth!

TRUCHELUT: Well, thank you for the opportunity to talk.

DOERING: So what was your reaction to this incredibly strong storm?

TRUCHELUT: It was a gob-smacking, head-spinning, kind of a day to be a meteorologist. The number of records that Melissa set, unfortunately at landfall, is extensive. It's going to take time to fully gather and process the data to truly understand Melissa's strength and intensity as it was making landfall. But, I mean, suffice to say, this was one of the very strongest storms anywhere in the Atlantic ever, and it was probably the very strongest to ever make landfall on any land mass bordering the Caribbean, the Gulf or the Atlantic in recorded hurricane history?

DOERING: Wow. What are some of the factors that helped fuel the strength of hurricane Melissa?

Hurricane Melissa is among the strongest storms ever recorded in the Atlantic. Nearly 77% of Jamaica lost electricity, and Cuba and Haiti also suffered significant impacts, with flooding in Haiti resulting in an estimated 25 deaths. The U.N. called Melissa a “tremendous, unprecedented devastation.” (Photo: Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

TRUCHELUT: Well, 2025 we've seen sea surface temperatures across the Atlantic basin be warmer than average, not quite reaching the record levels that we set in 2023 and 2024 but quite clearly, the third warmest temperatures on average across the Caribbean, going back to at least the 1970s and probably much longer than that as well. So not only were the surface waters of the western and central Caribbean 30 to 31 degrees Celsius, but those warm waters were extraordinarily deep as well. Waters above 30 degrees Celsius likely extended 65, 70, 75 meters below the surface. And that really mattered in this situation because Melissa was a slow mover. And usually when a hurricane stalls out over warm waters, it expends those waters. It basically evaporates the surface layers of the hot water. Water start to be transported kind of radially out away from the storm, and you start to upwell colder water with depth. Unfortunately, in this case, when Melissa started upwelling waters from beneath the surface, those waters were just as warm as the waters at the surface. So that is very unusual. Warm waters, or deep warm waters, cannot create a storm from nothing. You have to have a spark. You have to have an initial disturbance. You have to have favorable atmospheric conditions. You know, Melissa struggled for a few days last week after it formed, it didn't really intensify for three or four days because the atmospheric conditions were not in place. But as soon as everything lined up in the atmosphere, its intensification was explosive and sustained all the way from Friday through landfall on Tuesday, unfortunately.

DOERING: So if I understand you correctly, the hurricane is feeding off of this warm water at the surface, but then oftentimes we'll see these hurricanes actually dredge up cold water from below that, that actually slows them down. But that didn't happen in this case.

TRUCHELUT: Right. It certainly moved slow enough that if there was colder water beneath the surface, it would have probably been a factor and resulted in the hurricane's intensity leveling out at some point, in a way that just did not happen here.

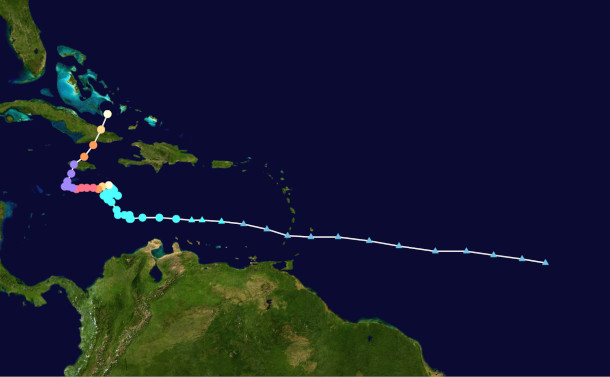

Hurricane Melissa made landfall on the island of Jamaica and continued on its path toward the Bahamas, also causing substantial damage in Cuba, and Haiti. Satellite imagery shows the storm’s path and category, with purple indicating a category 5 — the highest speed a hurricane can reach. (Color key: Teal: Tropical storm, Light Yellow: Category, Yellow: Category 2 Orange: Category 3, Pink: Category 4, Purple: Category 5) (Photo: HurricaneZeta, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DOERING: So Ryan, what do we know about how the climate crisis contributed to this particular storm?

TRUCHELUT: Well, I think that it's fair to say that while there is a history of very intense storms forming in the western half of the Caribbean in the latter third of hurricane season, October and November, I do think in this case, it's really not possible for the waters of the Caribbean to be as warm as they were and as deep as they were, minus climate change. Again, warm waters can't create a hurricane from nothing. The waters have been warm, and they've been sitting there all year, and this is the first hurricane to develop and move over the Caribbean. But it's a loaded gun, and it loads the gun even more powerfully to have that potential energy waiting for the right spark. So maybe in a non-anthropogenic climate change kind of world, perhaps you still get a Melissa. Does it claw its way down to 892 millibars and 185 or higher miles per hour, sustained winds? Maybe not quite that intense. But certainly the region does have a history of devastating storms, and as in a lot of cases, climate change is kind of acting on the margins here to make bad events a little worse, or sometimes a lot worse.

DOERING: Absolutely. So you know, as ocean temperatures continue to rise, what do you think the Caribbean region can expect in terms of future hurricanes?

TRUCHELUT: Well, basically, if you look at the 2025 hurricane season, I think what we saw this year may actually be a pretty decent guide to the kind of changes in how hurricane activity may shift over the next few decades. You know this hurricane season was forecast to be around average to somewhat above normal, but not hyperactive, not tremendously above normal. And now with Melissa happening, that's basically what we've seen. We've seen around 130 units of what's called Accumulated cyclone energy. If you go back over the last 75 years, the average is about 105, to 110. If you look back over the past 30 years, we've averaged about 125, 130 ACE units. So it's either above normal based on long term history, or right around average for what we've seen over the past few decades. But we've only seen 13 named storms, which is actually somewhat fewer than we've seen on average over the past 30 years. The truly extraordinary thing about the 2025 hurricane season is that of those 13 named storms, three of them were Category 5 hurricanes, and that's the second most that we have ever recorded in the Atlantic basin, second only to the 2005 hurricane season, where we had 28 named storms, and four of them were Category 5s. So we were extraordinarily efficient, for lack of a better word, in converting weak tropical storms into Category 5 monster hurricanes.

Dr. Ryan Truchelut is a leading professional in both forecasting and meteorological research, specializing in tropical cyclone risk and quantifying extreme event risk. He holds doctoral and master’s degrees in meteorology from Florida State University and serves as the chief meteorologist for WeatherTiger. (Photo: Ryan Truchelut)

DOERING: Yeah. I mean, we may not be getting more hurricanes, but it sounds like the ones that we do get may be bigger and badder and stronger and have more of an impact.

TRUCHELUT: There's certainly research that would suggest that. And now, with the 2025 hurricane season going under our belts, I say there's a fair amount of observations to suggest that as well. That's what I'm talking about here, that it's really these mega events, like Melissa, that are really the most impactful, both in economic and certainly in human terms. So, you know, it's very dangerous and frightening to be thinking about, you know, what if 20% of the of the storms every hurricane season turn into Category 4 or 5 storms? These kind of extreme events are well within the realm of possibility, and we need to build a society that's as resilient as possible to those risks.

DOERING: Ryan Truchelut is chief meteorologist with the weather consulting firm Weather Tiger. Thank you so much for joining us, Ryan.

TRUCHELUT: All right. Thank you.

Related links:

- Learn more about Dr. Ryan Truchelut and WeatherTiger.

- Follow Hurricane Melissa’s path.

- Drone footage and raw videos of the aftermath of Hurricane Melissa.

- El Pais Hurricane Melissa batters Cuba: ‘The night lasted too long’

[MUSIC: The Fenicians, “Road Song” on Stoned Moments, The Fenicians]

CURWOOD: Coming up, we meet a salamander with a smile. That’s ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the estate of Rosamund Stone Zander - celebrated painter, environmentalist, and author of The Art of Possibility – who inspired others to see the profound interconnectedness of all living things, and to act with courage and creativity on behalf of our planet. Support also comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Fenicians, “Road Song” on Stoned Moments, The Fenicians]

Gwich'in People Resist Arctic Drilling

A rainbow follows a storm over Vashraii K'oo (Arctic Village) bordering the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. (Photo: Emily Sullivan, Gwich'in Steering Committee)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Encouraged by US Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, back in 1960 President Dwight D. Eisenhower created what is now called the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. It’s the largest national refuge in the US and provides sanctuary for the abundant wildlife there, especially the Porcupine Caribou herd. They migrate in such great numbers that ANWR, as it’s called, has been compared to the Serengeti in East Africa. But since the discovery of vast oil and gas deposits in the region in the late 1960’s, the fossil fuel industry has set up shop, and now operates a major oil field in Prudhoe Bay, on the coast just west of ANWR. And for forty years there has been pressure to drill in ANWR itself. The first Trump Administration auctioned oil leases, only to have them canceled by the Biden Administration. And now the second Trump Administration is again opening ANWR for oil leases, though the current price of oil would make drilling uneconomical. On the front lines against drilling in ANWR are the Native Alaskan Gwich’in, and joining us is Kristen Moreland, chair of the Gwich’in steering committee. Welcome to Living on Earth, Kristen!

MORELAND: Thank you for having me.

CURWOOD: So on the coastal plain there where the Trump administration has decided to open up for drilling. Sometimes I've heard you folks call it God's country, explain that for me, please.

Kristen Moreland is the executive director of the Gwich’in Steering Committee based in Fairbanks Alaska. (Photo: Emily Sullivan, Gwich'in Steering Committee)

MORELAND: Our elders call our land Iizhik Gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit, which means the sacred place where life begins. We call it God's country, because we don't see the things that you guys see anywhere else. We don't see road development, we don't see refineries, we don't smell the pollution. All we see is pristine land our Gwich'in communities, we live along the migration route in Canada and Alaska, and have relied on the caribou for thousands of years. We use every part of the caribou. It has helped us sustain families and entire communities through harsh winters. Our winters get down to like 70 below. Our relationship is spiritual. The caribou we see it as a relative, not just a resource. Elders always told me that we are half of them, and they are half of us, and they carry half of our heart, and we do theirs the land and traditional knowledge. We follow the migration routes of the herd. We always had knowledge of our land, the weather, so we see the animal behavior, and we know that there is climate change, we know that there's something wrong. We have been doing this for years and we'll continue it, hopefully, if drilling doesn't happen.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about your reaction to this recent decision by the federal government.

A Gwich'in hunter scouts for the Porcupine caribou herd in the fall hunting season. (Photo: Emily Sullivan, Gwich'in Steering Committee)

MORELAND: The action by the Trump administration is a direct attack on the Gwich'in. We have for decades been a voice for the caribou and stood against the destruction of the Arctic Refuge. And when we heard this, we were just appalled. We didn't expect this decision, and it's just devastating to our people that they can just not care about human rights at all. They don't care about our people. They said that they talked to all the northern communities in Alaska, and we're all okay with it, but not one Gwich'in community have they talked to, not one. And we're the ones that are going to face the consequences of their actions.

CURWOOD: To the West of where you are, what's going on with the caribou there, and how might that be related to oil and gas extraction?

Gwich'in youth play outside the Vashraii K'oo (Arctic Village) Tribal Hall. (Photo: Emily Sullivan, Gwich'in Steering Committee)

MORELAND: So a study has showed mounting evidence that caribou in the North Slope oil field areas, even after generations, continue to stay away from man made features like pipeline, roads, buildings and show little sign of habitation to development, especially during the sensitive calving period. So we have seen, I think, like a 50% decline in the past two decades since oil development in the western Arctic, including severe declines in several Alaska herds that have led to hunting restrictions and negative impacts on subsistence communities. So we hear stories from different villages in the western Arctic, in Prudhoe Bay, around Prudhoe Bay, where there is no caribou. The elders are even posting on Facebook asking people for caribou bones, because our people boil caribou soup bones, especially our elders, they love soup. So that is very disturbing to us, because I can't imagine when our freezers can't be full anymore. I can't imagine not being able to bring a soup bone or anything to our elders, because our elders mean so much to me, and they need our meat. We need our meat to survive. We can't just go to the store and buy food there, it's not like down here. Like I'm in Fairbanks, and there's grocery stores here where I could go and buy food, but by time they make it to a village up like Arctic Village, where you have to fly two hours from Fairbanks to Arctic Village. You cannot drive up there. There's no road systems at all. So the freight cost us so much. I can't even tell you how much one pound of ground beef costs. It's like $40, $45 for one pound and by time it makes it up there, it doesn't look like meat, like it's just really dark, dark brown. When we get our meat fresh, it is perfect, there's no antibiotics, there's no nothing that they put in the food nowadays. We get it from the land, and it's not like that in our western communities right now, I can tell you that. All of the caribou herds are they have declined majorly.

Participants on the last day of the 2025 Emergency Gwich'in Gathering pose together in Vashraii K'oo. (Photo: Emily Sullivan, Gwich'in Steering Committee)

CURWOOD: What does it feel like to have land that is sacred to you and your community be caught up in this political situation?

MORELAND: When we go out on the land and we hunt for our caribou, our men goes out there and hunt for our caribou. And they have such a big pride when they come back and we see racks on their four wheeler, or however they're bringing it back to us, their smiles can just like tear you up because they're bringing home this meat to fill their freezers, to give to elders, to give to the community members. They are so proud, and we need that from our men, because we don't live in the city. We don't have therapists on hand. We live off the land. So, if that gets taken away from us, it will totally wipe us out as Gwich'in people. If oil drilling happens in the coastal plain, that is what will happen to us, as Gwich'in people we’ll no longer be here. There's still hope because no major oil companies want to go up there. Because we have lawyers that are on ground, working, as we speak. We have many allies on our side that is helping us. So, we have hope. That's hope to us. We know that there's so many people right now that is rooting for our land that doesn't want drilling. We're going to continue fighting, and we're going to continue raising our voices and concerns and putting up a fight.

Kristen Moreland collects water from the runoff of a nearby glacier. (Photo: Emily Sullivan, Gwich'in Steering Committee)

CURWOOD: Kristen Moreland is the executive director of the Gwich'in Steering Committee. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

MORELAND: Thank you so much Mahsi' choo.

CURWOOD: The US Department of Interior provided a statement about oil and gas extraction and the subsistence rights of Alaska Natives, and it’s posted on our website, loe dot org.

The Gwich’in nation is actively involved in protecting the porcupine caribou (pictured above) and their calving grounds in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge from threats like industrial development. (Photo: Frostnip907, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Related links:

- Learn more about the Gwich’in Steering Committee

- Reuters | “US Reopens Alaska Wildlife Refuge to Oil and Gas Development”

- The Guardian | “White House Approves Increased Oil and Gas Drilling in Alaska’s National Wildlife Refuge”

- KOTZ Local News | “Migrations Can Take Weeks Longer When Caribou Encounter Roads, Study Finds”

- Read the Department of the Interior Response Here

[MUSIC: Forest Wilson, “Among The Willows” on The Evening Redness in the West]

Serial Killers and Lead Exposure

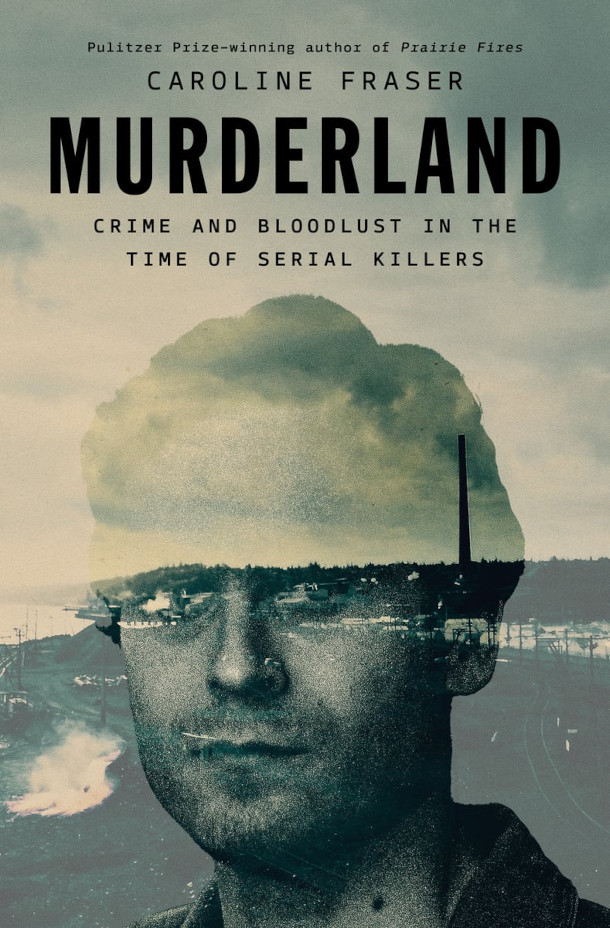

Caroline Fraser’s newest book, Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers. (Photo: Courtesy of Caroline Fraser)

DOERING: Now, serial killers may not be the type of topic you expect to hear about on Living on Earth. But hear us out, it’ll all make sense in a moment.

CURWOOD: From Ted Bundy and Jeffrey Dahmer to Charles Manson and the Zodiac Killer, serial killers are a distinctly American phenomenon. And Jenni, we have more serial killers in our history than the next ten closest countries combined.

DOERING: Oh, really? Yikes! I have heard though that within this country there’s kind of a hotspot for them.

CURWOOD: Oh yes there is or was anyway and many of these serial killers were active in the 1970s in the Pacific Northwest. Seattle-born author Caroline Fraser offers one possible explanation in her new book, Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers. She theorizes that the neurotoxin lead is key to this story. And she links dangerously high lead exposure from smelters and gasoline to the increase of violence and murders in her home state. Caroline Fraser joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

FRASER: Thank you, thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: You know, in some respects, this is an autobiography, and you provide some rather intimate details of your life, like juggling two boyfriends.

The 1970s marked a time of economic uncertainty and an uptick in violence in the Seattle area where author Caroline Fraser was growing up at the time. (Photo: Seattle Municipal Archives, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

FRASER: Yeah, this book covers a period of time when I was much younger. It was the, you know, 1960s, 70s, and I really wanted to give readers who may not be familiar with that era a kind of flavor of what it was like to be a young person then, to be a young woman in particular, and what it was like growing up in an era when all these serial killings started happening.

CURWOOD: So of course, aside from your own story, this book is about serial killers and the neurotoxin lead, as well as questionable development and even geological damage. So how did the idea for Murderland first come about with all those elements?

FRASER: Well, in the Northwest, where I'm from, of course, the question has always been raised year after year, of why Seattle and the Northwest in particular seemed to be kind of a hot spot for serial killers. And of course, the newspapers were very fond of this topic, you know, and constantly were talking about, what is it about this place? And people had all kinds of theories, you know, it was the weather or the rain, or maybe it was just too gloomy a place. Maybe it was the highway system. So I'm pointing at another kind of theory to address why this might have happened, and I also am hoping that no matter what you think of this theory, whether you agree or don't agree, you may learn something about the ecological history and the environmental damage that happened in this place over the past 100 years or so.

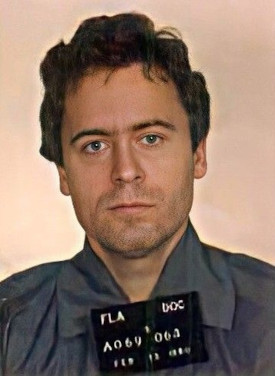

One of the most infamous serial killers in American history is Ted Bundy, who grew up in Tacoma, Washington, not far from Fraser’s childhood home. (Photo: Florida Department of Corrections, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: The book itself, I think, opens in your hometown of Seattle in the 60s. Just set the stage for us for a moment. What was going on at that time?

FRASER: Yeah, Seattle has always had a very up and down, hot and cold economy. So the 1970s for example, was a recession. A lot of contracts were canceled at Boeing. People weren't building as many houses. People were losing their jobs, and gasoline had become very scarce and expensive. So it was a troubled time nationally and regionally for Seattle, and that was the time when I was growing up there and all these bizarre things started happening. You know, the country nationally saw a real rise in violent crime, and so did the greater Seattle area.

CURWOOD: Your book also links exposure to pollutants such as lead to the abnormally high level of crime, including serial killers in the Northwest. Let's focus for a moment on Ted Bundy, a famous serial killer. He grew up in the Tacoma area, not so many miles from where you grew up. Talk us through the connection between Ted Bundy's exposure to lead and his rise as one of America's most infamous serial killers.

The American Smelting and Refining Company, or Asarco, owned the smelter in Tacoma, which emitted dangerous levels of lead, arsenic, and other toxins. Above, a 1972 photograph of the smelter towering over a nearby home. (Photo: Gene Daniels, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

FRASER: Well, yeah, I mean, when I was 13, when he began this kind of spate of abductions and rapes and murders, nobody had really heard of the term serial killer. It's not that they hadn't existed. I mean, there have always been people like Jack the Ripper, for example, but the whole phenomenon of serial killers did not yet exist in the way that we know it now, both from the media, from Hollywood, from books, etc. So it was really kind of an unknown thing. Now, of course, everybody has heard of Ted Bundy, but one of the things I became really interested in was where he grew up, because he was born, actually in Vermont, but then as a young child, moved to Tacoma, Washington. And Tacoma had both a very high crime rate, and it also had a lead smelter. It was putting out large amounts of lead and arsenic particulates into the air throughout the whole period when Ted was growing up. And we now know, thanks to research and mapping that's been done, exactly how much lead was in Ted Bundy's front yard and his backyard. We know how much arsenic was there. So he was exposed to a significant amount of these toxins. Whether that contributed to what he ended up doing, we certainly can't know, we can't prove that. But it's an interesting fact, because he always seemed like somebody who didn't entirely seem to have developed in a normal way. Like many serial killers, he had fantasies of rape and murder from a very, very young age. So that was something that I was interested in looking at, especially when you see other acts of serial murder that are associated with that same area.

CURWOOD: And by the way, Ted Bundy was born, as you write in your book, to an unwed mother. That mother had been exposed to lead as well, given her family's business.

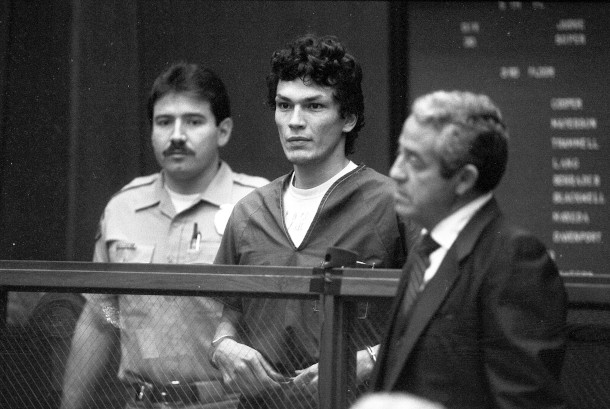

Otherwise known as “The Night Stalker,” Richard Ramirez was a serial killer who grew up in El Paso, Texas, home to another Asarco smelter. (Photo: Iris Schneider, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

FRASER: Yeah, that's very true. Ted Bundy's mother grew up in Philadelphia, which has been called the city of smelters because there was so much smelting activity going on there in the run up to World War II, and throughout World War II. And of course, Ted Bundy is born in 1946 just after the end of the war. There are several of these killers who I write about who really were exposed in multiple ways to lead throughout their lives, both as children and as adults, and I think it is a fair question to ask what that might have resulted in.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about how the stories of the other serial killers are linked to Bundy, the geography and the exposure to the neurotoxin: lead.

FRASER: Well, one of the other killers who I talk about is Gary Ridgway, who also grew up in the Seattle, Tacoma area, and as a child, used to play, according to his brother, in piles of copper tailings, which are the leftover rocks from mining, which themselves contain significant amounts of the kind of toxins that you see coming out of smelters. He grew up near an airport at a time when a lot of general aviation aircraft were using leaded fuel. And as an adult, he worked painting the cabs of trucks, which was at the time using leaded paint. So he's exposed to lead throughout his entire life, and I think he makes a really interesting example of this kind of exposure. Another killer is Richard Ramirez, who grew up in El Paso, Texas, where the company that owned the smelter in Tacoma had another smelter. This was Asarco, the American smelting and Refining Company. So El Paso had been the recipient of the fallout from that smelter for many, many years. And Richard Ramirez, too shows a lot of developmental difficulties as a child, somebody who had seizures and developed a very, very kind of violent fantasy life as a kid, which then he acted upon some years later as a young man in Los Angeles. But I thought it was fascinating that although we know Richard Ramirez from what he did in LA, he really grew up in a completely different place and was exposed to lead.

The EPA began to phase out leaded gas in the 1970s after evidence of severe public health impacts linked to lead poisoning came to light. Children were especially vulnerable, suffering developmental problems, low IQ, and behavioral issues. (Photo: Joe Mabel, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: So talk to me about the gender connection here to serial killers, I think the numbers that you said is less than 8% are women, almost always men. Why do you think that is and how might that be related to their exposure to lead in childhood and adulthood?

FRASER: Yeah, there have been some studies on this that show that the development of the male brain is affected much more grievously, I think, than the development of the female brain in childhood, if you're exposed to lead. The development of parts of the brain like the frontal cortex, where you have a lot of the parts of the brain that control impulsivity and aggression, and they've shown this through brain scans of people who've been exposed to lead, and the effects are much more notable in men than in women.

CURWOOD: Let's talk for a moment about the Cincinnati Lead Studies. What were the findings of that research, and why are they still relatively unknown?

FRASER: Yeah, that's a great question as to why they're not as widely known as they should be. But yes, the Cincinnati studies were a very long term series of studies that looked at kids who were exposed to varying amounts of lead and then followed them until they became young adults. The findings, I think, fairly strongly, showed a correlation between lead exposure in children and in pregnant women and the behavior of these kids after they grew up in the, you know, teen years, in the early 20s, when most violent crime is committed. There was a real strong suggestion that lead was responsible, to some extent, for a rise in violent behavior and impulsivity, in heightened aggression, in juvenile delinquency. So it's a very important series of studies. I'm not sure why it hasn't received as much attention as it should have, but I suspect a lot of that had to do with the ways in which the lead industry itself was dedicated to convincing people that lead was safe and that this was really merely a correlation, that it wasn't something that we should be concerned about. I mean, they were dedicated for years to covering up the actual information and studies that showed that lead is not safe and that there's no amount of lead that is safe in the human body.

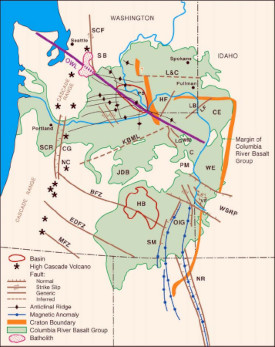

The Olympic-Wallowa Lineament, shown above in purple, is a geologic fault line that runs diagonally through the Pacific Northwest. Fraser warns that the OWL could contribute to a major earthquake in the Seattle area at any moment. (Photo: B. S. Martin, H. L. Petcovic, S. P. Reide; Wikimedia Commons; Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So what does the removal of lead from gasoline tell us about lead and violent crime?

FRASER: Well, the fascinating thing about the correlation between leaded gas and violent crime is that you see a very sharp rise in violent crime in the 1970s, it was over 10 per 100,000 people, and we'd never in the records of the FBI, we had never reached that before. And that correlates with the post World War II boom in people driving, which begins in the 1950s, you know, people are buying more cars and commuting longer distances. There's more leaded gas entering the atmosphere. So, you know, we talked about the Cincinnati studies that showed that children exposed to lead may develop heightened aggression 20 years later. So that's what you're seeing. You're seeing 1950s the amount of leaded gas is really increasing in the atmosphere. Then when these kids become around the age of 20 in the 1970s, 20, 25, you see the rate of crime rising in the 70s and 80s, and continuing through the early 90s. And what happens during that period is that, you know, we have the Clean Air Act. We have the EPA being established. We have regulations that are beginning to come in to affect leaded gasoline, and then you see a very sharp drop off beginning to happen with violent crime.

In recent decades, people have moved in high densities to cities that are vulnerable to earthquakes, including Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Above, a street market in San Francisco after an earthquake in 1906. (Photo: National Archives, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

[MUSIC: Alice In Chains, “Rotten Apple” on Jar Of Flies, Sony Music Entertainment Inc.]

CURWOOD: Just ahead, We’ll continue our conversation with Caroline Fraser about her book Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Waverley Street Foundation, working to cultivate a healing planet with community-led programs for better food, healthy farmlands, and smarter building, energy and businesses.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The LoFi Bear, “Main Title” Single, The LoFi Bear]

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Caroline Fraser’s book Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers has a deeper theme than a set of mere murder mysteries. A key part of her book considers how our society tends to ignore and deny the science of major risks such as lead exposure. So Murderland includes the story of the Olympic-Wallowa Lineament, or OWL, a geological fault line that runs through the Northwest. Caroline, you write that the land on top of the OWL is prone to floods, earthquakes, tsunamis, and other disasters, and yet we build on it anyways. Please tell us about OWL, and how it fits into your narrative...

Fraser blames large corporations, such as Asarco, for purposely concealing the alarming health consequences of their industry from the public. Above, an Asarco site in Garfield, Utah in 1942. (Photo: Andreas Feininger, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

FRASER: Yeah, the OWL is another image that I kind of fell in love with. It cropped up when a map maker, a cartographer, was drawing a map of Washington State. And this map was so detailed, and when he'd finished it, he kind of glanced across it and noticed that there seemed to be a kind of a trough that was created, sort of a weird visible line from the tip of Northwestern Washington down through the state. And he wondered what that was. He thought it probably had something to do with an earthquake fault, which is, I think, the leading theory now, but I loved the image of it and the metaphor that it makes because it suggests both the hazards of the natural world, you know, earthquake faults, and the hazards that we put ourselves in by being drawn to the places where these hazards exist. I mean, we have now moved in such large numbers and such density to places like Seattle and San Francisco and Los Angeles, where there are these earthquake faults. I think this is again a metaphor for what we do to ourselves, and both the beauty of the region and the dangers that it poses.

CURWOOD: I think in geologic history, there was a major kind of earthquake in that area, maybe some 300 years ago that killed a lot of people.

FRASER: Yes, in the 1700s, and you see fascinating records of this in Native American culture, in stories, in art and memory. And that's just a kind of fascinating record of what we're up against, because they believe that those fault lines and the Juan de Fuca plate that is being forced under the continent of North America, that that's going to cause another major earthquake of that same strength anytime now or in the future. And that's quite alarming, given that now there are so many more people and bridges and tunnels and skyscrapers and all of the things we bring along with us.

CURWOOD: And you don't live in the Seattle area any longer.

FRASER: No, no I don't.

CURWOOD: So there seems to be a theme of scientific denial throughout this story. The proximity of danger caused by this OWL fault line and the smelters is just largely ignored by the public. Why do you think that is?

Caroline Fraser is a Pulitzer Prize-winning author of four nonfiction books. She grew up in Seattle and currently resides in New Mexico. (Photo: Courtesy of Caroline Fraser)

FRASER: Yeah, I don't think we're very good at planning far into the future, even when we know about things like the earthquake faults. I mean, we now know so much more about that history than we did even 20, 30 years ago. But we still have a very hard time preparing for things like that. I mean, you see this in the government preparations for pandemics and so forth. It's, it’s very hard to get people to invest money and time in things that don't seem to be an immediate problem. And I think people just don't like to think about it. They don't like to think about the ramifications of what might happen, you know, of what could be waiting for us. So I think as human beings, we just come with some inherent limitations. You know that that keep us from doing things that are in our best interests. But obviously there are enormous stakes too, financially. I mean, for decades, it was very hard to get the smelter companies, for example, to deal with anything that they were putting into the air. They didn't even want to release any of the information they had. The system is really broken, I think, in terms of we just wait until these corporations have done the worst that they can do, and only then do we go after them to clean it up. So I think until we develop some kind of system that puts the onus on the corporations to begin with, we're really just going to always be behind the eight ball.

CURWOOD: Some would say that applies to the climate emergency as well.

FRASER: Absolutely. You know, if you look at what Exxon and Standard Oil and so many of these corporations have done, they knew about this. They knew about it for decades and lied about it, which is exactly what the smelters did. So when you're trapped in that kind of reality, I think you have to ask yourself, do we need to really reform the system from the ground up? And we do, but it's increasingly difficult to see how to make those kinds of changes.

CURWOOD: And before you go, to what extent does this book scratch the itch that you had going back many, many years, when you were living in a community where there was a lot of fear about serial killers?

FRASER: Yeah, I think that it was an enormously sort of fascinating thing for me to be able to confront some of these stories, some of these theories, and try to make some sense out of it. Whether, you know, you believe the theory or not, I think there's a whole history of environmental damage that was perpetrated on the Northwest, a place that I love dearly, and on many other places around the American West and in the United States during that era. And the history is important, whether you care about the serial killer angle or not. It's a really troubling and important history that I think if we understand it, it might help us make better decisions in the future.

CURWOOD: Caroline Fraser's book is titled "Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers." Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

FRASER: Oh, thank you. It's been a great conversation.

Related links:

- Learn more about Caroline Fraser.

- Buy Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers and support both Living on Earth and independent bookstores.

[MUSIC: Nirvana, “Come As You Are” on Nevermind (Remastered), Geffen Records]

Science Note: Axolotls Released to Wild

The axolotl (ambystoma maxicanum) is an aquatic salamander with external gills and a finned tail. (Photo: Mike Licht, NotionsCapital.com, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: We head to Mexico now, where in some homes altars are brimming with gifts for departed loved ones. But first this note on emerging science about an amphibian endemic to Mexico, with a bit of a cult following.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

LYMAN: Axolotls, aquatic salamanders with feathery gills that look like they’re always smiling. These amphibians are endemic to just one lake in Mexico. There are lots of axolotls in captivity, as pets or research animals, but there are estimated to be only 50 to 1,000 of the endangered salamanders left in the wild. But conservation biologists recently reported that releasing axolotls that were bred in captivity into restored and manmade wetlands, may help to bolster their populations.

Axolotls are endemic to Lake Xochimilco in Southern Mexico. Scientists have recently released one group of captive-bred axolotls into one of the lake’s restored canals. (Photo: Hernán García Crespo, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

A team led by Alejandra Ramos, a scientist at the Universidad Autonoma de Baja California in Ensenada, Mexico, released 18 captive-bred axolotls with implanted radio transmitters into two wetlands in Mexico City. One group was released into a restored canal in the axolotl’s native habitat — Lake Xochimilco, and the other into a pond in an artificial wetland. Researchers then tracked the aquatic salamanders for 40 days.

The scientists reported that all of the axolotls in the study survived, and three gained weight, indicating that they were successfully hunting prey in their new home. The data also showed that the amphibians traveled farther early in the experiment, perhaps exploring before they found hunting and hiding spots.

There are many axolotls kept as pets or used for research purposes, but only 50-1000 still exist in the wild, making them an endangered species. (Photo: Paul Hutchinson, Bureau of Land Management, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

Reintroduction is really a plan B, said Luis Zambrano, an ecologist at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in Mexico City. The researchers' main goal, Zambrano said, is to improve the aquatic habitat for axolotls already living in the wild.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

Related link:

Inside Climate News | “Captive-Bred Axolotls Were Successfully Introduced to the Wild. Can This Work for Other Species?”

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

The Many Layers of Dia de los Muertos Altars

A three-level traditional Dia de los Muertos altar from the alcaldia Milpa Alta in Mexico City. (Photo: Eneas de Troya, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: Halloween comes a day before the Day of the Dead, or Dia de Los Muertos, widely celebrated in Mexico. It’s a yearly tradition for Living on Earth Producer Paloma Beltran, and from her perch in Mexico City she tells us how the celebration has taken on new meaning.

BELTRAN: As October turns to November, thousands of candles are lighting up across the world, welcoming back the souls of family and loved ones who’ve passed away.

The Day of the Dead, or Dia de los Muertos in Spanish, is a holiday celebrated throughout Mexico and other parts of the Americas.

The idea is that by setting up a colorful altar we will attract and welcome the spirits of the departed back home.

I know it may seem like an exceptional kind of reunion but a lot of people across the world celebrate the departed in one way or another.

I should clarify that I’m no expert on Dia de los Muertos and the specifics on what to incorporate vary across regions and family traditions.

You know, that’s just how culture works.

But I would like to share a bit of what I learned throughout this year’s planning process.

Traditional altars are colorful, maximalist, and full of life!

There are a few options: 2 levels representing heaven and earth, 3 levels representing heaven, purgatory and earth, or the more elaborate 7 levels portraying different steps to heaven.

An elaborate offering in Puebla, Mexico. (Photo: Alexgarcesm, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY SA 4.0)

Some historians link altars to the 9 stages needed to reach Mictlan, the underworld of Mexica mythology.

Day of the Dead altars or altares can be dedicated to multiple family members, friends, mentors — basically anyone who’s passed away and that you’d like to honor.

There’s even a day of the dead dedicated to pets on October 27!

When building the altar you can go the eco-friendly route like I did and reuse cardboard boxes to set up the structure. It really doesn’t have to be expensive!

Altares represent a connection to the circle of life as well as the four elements of nature:

water, wind, fire and earth.

A glass of water signifies purity.

Papel picado is both placed on Dia de los Muertos altars and used to adorn the streets of Mexico during the season. (Photo: Luis Alvez, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The light and delicate texture of papel picado or perforated paper represents wind and the fragility of life.

Some say the holes in the tissue paper allow souls to travel and visit us.

Fire is invoked by lit candles, which serve to light the path and guide the spirits of the deceased home.

For Earth, we offer seeds, fruits and the dead’s favorite foods as well as beverages. If your loved one enjoyed fresh lemonade for example or a cold beer make sure to place it on their altar, because who wouldn’t want to be received with a cool drink after a long journey!

And there’s one extra special element called Copal.

It’s an aromatic incense used to purify the environment and also guide the spirits to the altar. This resin comes from a tree endemic to Mexico and Central America.

It is found in the warm areas of the states of Michoacan, Chiapas, and Oaxaca, Puebla and more.

Cempasuchil flowers or petals are usually placed at the bottom of the structures.

The colorful orange and yellow petals, as well as the fragrant scent, once again are meant to attract the departed to the altar.

Flor de cempasuchil. (Photo: Jmndz, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

This year’s altar is especially significant for me and my partner since my father passed away recently.

On my father’s side my family has been farming for generations.

To honor my father’s connection to the earth and agriculture, we’re incorporating alfalfa, cotton flowers and a bit of dirt from the fields he worked with and loved dearly.

It’s honestly been an opportunity to call up family and friends, cry and laugh as we shared anecdotes about all our loved ones who have passed.

Like remembering how my grandfather loved garlic and would even eat it raw, we used to joke around and call him a “vampire slayer”.

Or learning that my father had a perm in college during the 70s, who would’ve thought!!

For us it’s been a healing experience.

Dia de los Muertos is an invitation to cherish the joys of those who have passed away and what they loved about this earth.

It’s also an opportunity to host them once again in your home with intention and care.

And by keeping them close in our memories, we ensure that they are never abandoned or forgotten.

DOERING: That’s Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

Related links:

- National Museum of the American Latino | “Day of the Dead resources”

- National Geographic Kids | “Day of the Dead”

- Rutgers | “What Is the Meaning Behind Day of the Dead Symbolism?”

[MUSIC: Un Millon de Primaveras - Puro Mariachi Karaoke - Vicente Fernandez - Tono Original]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Sophie Bokor, Daniela Faria, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jade Poli, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram at living on earth radio, and we always welcome your feedback at comments at loe.org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth