Fungi and Climate Resilience

Air Date: Week of January 16, 2026

Toby Kiers is a 2025 MacArthur Fellow and a cofounder of SPUN, the Society for the Protection of Underground Networks. (Photo: Seth Carnill)

Mycorrhizal fungi form intricate and vital partnerships with plants through enormous underground networks that could help ecosystems and agriculture withstand climate impacts. But these fungi are threatened by habitat loss, nitrogen pollution and more. 2025 MacArthur Fellow Toby Kiers is leading fungi research and conservation efforts. She shares with Host Jenni Doering the wonders of fungi and why they’re worth protecting.

Transcript

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

When most of us think of fungi we probably picture the mysterious mushrooms growing in our backyards, or the yeast in our sourdough starter. But for 2025 MacArthur Fellow Dr. Toby Kiers, fungi are at the root of our entire world, literally. Toby studies mycorrhizal fungi, which form intricate and vital partnerships with plants through enormous underground networks known as mycelium. Just a gram of soil, about a quarter teaspoon, can contain nearly 300 feet of mycelium. But habitat loss, nitrogen pollution, and more are endangering these amazing networks. So, much of Toby Kiers’ work revolves around researching and protecting them, and she’s here with me now to discuss. Welcome to Living on Earth, Toby!

KIERS: Thank you so much for having me.

DOERING: And by the way, congratulations.

KIERS: Thank you. Such incredible news.

DOERING: So I'm not sure that people understand just how much plants depend on fungi. Talk to me about this incredible relationship.

KIERS: Yeah, fungi, they really lie at the base of life on Earth. They're key ecosystem engineers, and one of the most important roles they play, I think, is to build soil. So if you think about our soils, right, they store about 75 percent of terrestrial carbon, and you're not going to believe this number, but they also contain about 59 percent of the Earth's biodiversity, so a huge amount of biodiversity underground. And all of this life is possible because of a class of fungi called mycorrhizal fungi. That's a big word, mycorrhizal fungi, but mycos means fungi, and rhizal means root. And these are basically network forming fungi that associate with plants. It's not just some plants. It's about 80 to 90 percent of all plant species. And if you were to picture these networks, they facilitate these very crucial exchanges. And so, as a result, you can kind of think of these fungi as like a circulatory system for the Earth.

DOERING: Toby, by the way, fungi, fungi, funga, what's the right way to pronounce this here?

KIERS: That's the beauty of the word, is that it can be pronounced any way that you feel comfortable, fungi, fungi. And anyway, it's a very inclusive word.

DOERING: And what exactly is this partnership between the plants and the fungi, like, what are they sending back and forth?

KIERS: This is a partnership based on carbon to nutrient exchange. So the plants are sending carbon down into the fungal network, and the fungi need that carbon to be able to survive, to build their bodies, to process energy. They need that plant carbon, but it doesn't come for free. In exchange, they are out collecting phosphorus and nitrogen and water and providing all kinds of benefits to the plant. So they put those nutrients in their network and send it up to the root system. And it's beautiful. If you were to actually look inside a root system, there's this structure called the arbuscule, and that's where the exchange of carbon and nutrients take place, and it's sort of like this beautiful tree like structure inside the plant cell.

DOERING: And each of these partners make sure that it's a fair trade, don't they?

KIERS: They do. So, over this evolutionary relationship that's about 450 million years old, both partners have evolved very clever strategies to be able to make sure that it's a fair trade. And it's not that it's fair every time, but just that on average, that both partners are benefiting from the relationship.

Kiers studies mycorrhizal fungi, which are primarily underground and form crucial partnerships with plants. In the photo above, the mycorrhizal mushroom Cortinarius albomagellanicus emerges from a hyper-diverse but hidden underground fungal community in Tierra de Fuego, Chile. (Photo: Mateo Barrenengo)

DOERING: So I think one of the most mind blowing aspects of this is realizing that I don't know these networks don't necessarily have a mind like we do, you know, like a centralized nervous system. Or maybe they do. I don't know. How exactly are these decisions being made? And what's driving this, I guess?

KIERS: Well, welcome to our lab. I mean, we spend most mornings waking up thinking, "How is information processed across a network that has no central nervous system?" I mean, growing up as biologists, I think we always think of intelligence as having a central nervous system, some sort of central processing, like in humans, like a brain. Fungi are very different, yet we know that they're able to engage in these very sophisticated trade strategies. What I mean by that is that through about 10 years of work, we've been documenting how they move resources in a way that really maximize the amount of carbon that they get from a plant system. So they'll do things like hoard nutrients in their network until they get a higher price, or they'll move it actively across the network to a place where demand is higher and they're able to get more carbon per unit phosphorus. So we've been doing these kinds of experiments for about 10 years that show these very sophisticated trade strategies. And so now the big question is, how do they do it? How are they sensing all the conditions, again, across billions of growing tips?

DOERING: So I imagine that while a lot of this research is taking place in your lab, to what extent do you have to go out and collect samples from all over the world, all kinds of different soil and and where is that happening?

KIERS: Well, this was the real motivation for starting SPUN. So SPUN stands for the Society for the Protection of Underground Networks. And it had a really like simple but audacious mission, and that's to actually go out and map the networks of mycorrhizal communities that regulate the Earth's ecosystems, and then start advocating for their protection. And so SPUN started, really, to transform how fungi are used in climate change strategies and conservation and restoration efforts. But to be able to do that, you need to map. You need to understand which mycorrhizal communities are where and what they're doing. So that's what we started doing. We, in 2021, we started working with researchers all over the world and local communities across, I guess, some of the most understudied ecosystems on Earth, and start generating these global data sets of what these fungi, who they are, and what they're doing.

Underground fungal networks are crucial to the vast majority of plant species’ survival, not just plants in forests or jungles. (Photo: Mateo Barrenengo)

DOERING: I mean, it sounds a lot like a network. I mean, it sounds like, literally, the form that SPUN has taken is something akin to the fungi networks that you're studying.

KIERS: It is. It's celebrating decentralized ways of doing science, and I think that's really important. It's really a celebration for decentralized ways of thinking and operating that fungi have mastered. So in this case, it's networks of scientists all over the world trying to analyze local patterns of underground biodiversity and then coming together to make this global map. And we're really excited about, even in the last four years, what SPUN and all of these researchers around the world has accomplished. Just in July, we published something called the Underground Atlas, which is a very cool resource for anybody to look up. And you can go and actually enter a location anywhere in the world. And what it does is zoom in on that location and give a prediction for mycorrhizal richness, which is a measure of biodiversity. So you can look at patterns all over the world of something that's been so hidden for so long. And I think what's important is that it's not just about this one idea of like, let's make a map, but instead, it's really about trying to use fungal data for applications, for everything from policy to litigation to land management. So restoration is an important field right now, and we know that restoration success could really be improved if people are also thinking about underground restoration and what underground fungal rewilding would look like. And so with this new map, what we can do is actually we can offer benchmarks for what we think an intact, healthy mycorrhizal biodiversity community should look like, and that can be used as a target for people that are working on degraded land trying to restore an underground ecosystem.

DOERING: Wow, yeah, it sounds like you don't just want this to be research that's interesting. You want it to make a difference in the world too.

KIERS: Yeah, exactly. And there's really a need right now to focus on what we call the three F's. So we used to just say flora and fauna, but now we're saying flora, fauna, and funga. It's really important for conservation efforts around the world to embrace that third F and start conserving fungi.

DOERING: So tell me more about climate change and fungi and how they could maybe be part of the solution, or a solution, at least, to helping us weather the storms ahead.

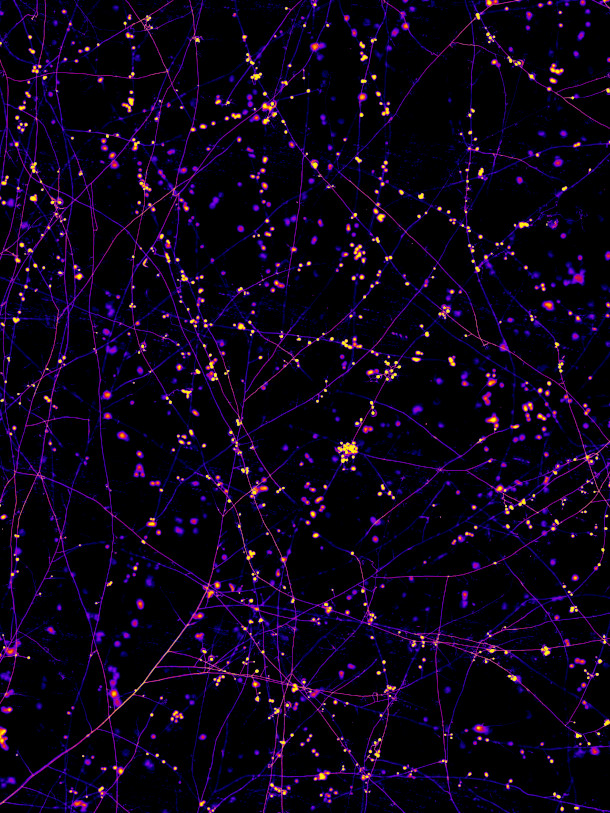

A photo of mycorrhizal fungi network. Mycorrhizal fungi form vast underground networks that transport nutrients in a way to maximize how much carbon the fungi receive from the plants. Despite the research, no one quite understands how the fungi do this without a central nervous system. (Photo: Loreto Oyarte Gálvez - VU Amsterdam)

KIERS: Well, we know that fungi lie at the base of life on Earth, and so we have to protect these fungi. The amount of carbon that is going down into mycorrhizal networks is astonishing, and we need to keep that circulatory system alive. Fungi create this scaffolding underground. You can really think of it as like a physical scaffolding that holds all of these underground ecosystems together, and if you lose that scaffolding, then these ecosystems wash away. And so when we're thinking about climate change and all of the global change that we're facing, fungi offer all kinds of solutions, whether it be to carbon drawdown to protection against pollutants and heavy metals, to sustainable sources of nutrients. They offer solutions that we just haven't considered before. So it feels like it's a great time to start collaborating with fungi.

DOERING: Could you please tell us a story, to give us a sense of what some of these projects that SPUN is undertaking, what they look like?

SPUN conducts research all over the world to map ecosystems’ fungal communities, including in difficult to reach places, like this forest in Ghana. (Photo: Natalija Gormalova)

KIERS: Of course. So some recent ones, recent expeditions that I've been working with are, for example, in Tunisia. Tunisia is an incredible country that's facing extreme changes as we face the climate crisis in terms of drought, and so we had an expedition with scientists in Tunisia to really understand the fungal communities that allow plants to adapt to extreme drought. So that involved collecting fungi right on the edge of the Sahara and trying to understand what was unique about these fungal communities that allowed plants to survive such harsh conditions. This is particularly important for agriculture. What are the fungi that are going to allow our crops to survive in the future as conditions get more and more extreme? In other cases, it's working with fungi that might be destroyed or lost to global change. We had a project with scientists in Ghana, for example, where we are trying to map the fungal biodiversity along the coast, Ghana's coast, which is facing extreme changes from sea level rise. So one worry that we have is that whole fungal communities are going to disappear. How do we protect those fungal communities? So in some cases, it's about leveraging and working with fungal communities, let's say, for agriculture, and in other cases, it's about drawing attention to really important fungal communities that may be lost and trying to protect — sort of, you could think of them as libraries of solutions — before they disappear.

DOERING: So what are some of the threats to underground fungal ecosystems, and how are they different from the threats to above ground ecosystems?

KIERS: Well, in some cases they're the same, and in some cases they're very different. So of course, a lot of these communities face threats from things that you'd normally think of, like deforestation, erosion, agricultural practices, but there's hidden dangers to fungal communities, things like nitrogen from the rainwater. The rainwater is becoming more and more nitrified, more and more nitrogen coming down in rainwater, and that really changes the balance between how much carbon that plants are going to feed to the fungi, if they're just getting so much nitrogen from the environment already. So they stop providing carbon to some of these mycorrhizal communities because they're getting so much nutrients already from the rainwater. And if there is this loss of carbon, then a lot of these fungal communities aren't surviving. So other things like dead wood, you know, you can think of some habitats where land managers are taking dead wood out of ecosystems, and that can really change the balance of which fungal communities survive. So there's a lot happening in terms of threats that are kind of hidden, that we don't really think about, for things that are underground. I think this is a real problem, though, the destruction of these underground networks. It can increase global warming. It can accelerate biodiversity loss. It can disrupt nutrient cycles. So there's a real urgency here. When we look at the work that SPUN has been doing, I think it's something like less than 0.02 percent of the Earth's surface has been mapped for mycorrhizal fungi.

DOERING: Oh my gosh!

KIERS: So there's a huge amount of work to do ahead.

DOERING: What do you think we humans can learn from these cooperative underground networks?

KIERS: Again, I think we can learn about how to work in a decentralized way. So much of our science until today has been very top down, and we haven't really embraced this way of collective learning, of how we learn across very diverse ecosystems and habitats and ways of thinking, and fungi are so good at that. So if there's one thing we can really do, it's embrace this decentralized way of learning and thinking.

DOERING: It's something we could really use in this world right now, I think.

KIERS: Exactly! It's this idea of partnerships, right? And partnerships are always fragile. So if you think about this partnership between plants and mycorrhizal fungi, there's always going to be a tension that the fungi really need a lot of carbon and the plants really need a lot of nutrients. But over time, there's this beautiful balance that emerges because of that tension. So we shouldn't be scared of tension that can really drive evolutionary innovation. It can drive all kinds of ideas. But at the base of that is a really healthy partnership.

DOERING: Toby Kiers is the university research chair and a professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolution at VU in Amsterdam. She's also a co-founder of the Society for the Protection of Underground Networks and a 2025 MacArthur Fellow. Thank you so much, Toby.

KIERS: That was so fun. Thanks so much.

Links

Learn more about The Society for the Protection of Underground Networks.

Read Toby Kiers’ MacArthur profile.

Find out about the mycorrhizal fungi in your area by using the Underground Atlas.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth